Abstract

2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD, dioxin) and related dioxin-like chemicals are widespread and persistent environmental contaminants that produce diverse toxic and biological effects through their ability to bind to and activate the Ah receptor (AhR) and AhR-dependent gene expression. The chemically activated luciferase expression (CALUX) system is an AhR-responsive recombinant luciferase reporter gene–based cell bioassay that has been used in combination with chemical extraction and cleanup methods for the relatively rapid and inexpensive detection and relative quantitation of dioxin and dioxin-like chemicals in a wide variety of sample matrices. Although the CALUX bioassay has been validated and used extensively for screening purposes, it has some limitations when screening samples with very low levels of dioxin-like chemicals or when there is only a small amount of sample matrix for analysis. Here, we describe the development of third-generation (G3) CALUX plasmids with increased numbers of dioxin-responsive elements, and stable transfection of these new plasmids into mouse hepatoma (Hepa1c1c7) cells has produced novel amplified G3 CALUX cell bioassays that respond to TCDD with a dramatically increased magnitude of luciferase induction and significantly lower minimal detection limit than existing CALUX-type cell lines. The new G3 CALUX cell lines provide a highly responsive and sensitive bioassay system for the detection and relative quantitation of very low levels of dioxin-like chemicals in sample extracts.

Keywords: TCDD, dioxin, CALUX, Ah receptor, bioassay

2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD, dioxin) and structurally related dioxin-like halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons (HAHs), including polychlorinated/brominated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PC/BDDs), dibenzofurans (PC/BDFs), and biphenyls (PC/BBs), are ubiquitous, persistent, and highly lipophilic compounds found in diverse environmental, biological, food, and other matrices (International Program on Chemical Safety, 1998; Safe, 1990). Exposure to and bioaccumulation of TCDD and related HAHs can produce a broad spectrum of species- and tissue-specific toxic and biological effects, the majority of which appear to be mediated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a soluble ligand-dependent transcription factor to which these chemicals bind with high affinity (Hankinson, 1995; Safe, 1990). Following ligand binding, the cytosolic ligand:AhR complex translocates into the nucleus and is released from its associated protein subunits by its dimerization with the structurally related nuclear protein Ah receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), converting the resulting ligand:AhR:ARNT complex into its high-affinity DNA-binding form (Denison, Phelan, and Elferink, 1998; Hankinson, 1995). The binding of the liganded AhR complex to its specific recognition site, the dioxin-responsive element (DRE), stimulates transcription of adjacent downstream genes and persistent activation of the AhR signaling pathway by metabolically stable ligands (like TCDD) appears to be primarily responsible for the majority of the diverse toxic effects of these compounds (Denison, Phelan, and Elferink, 1998; Denison, Seidel, et al., 1998; Furness and Whelan, 2009; Hankinson, 1995; Safe, 1990). Given the extreme potency and highly toxic nature of TCDD and related TCDD-like HAHs, their detection and quantitation in diverse matrices that humans and animals can be exposed are required by most international regulatory agencies.

Sophisticated cleanup procedures followed by high-resolution analytical methodologies (gas chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry [GC/HRMS]) allow separation, identification, and quantitation of individual PC/BDD, PC/BDF, and PC/BB congeners, and this methodology is considered the “gold standard” for quantitative determination of these dioxin-like chemicals in sample extracts (Behnisch et al., 2001b; Denison et al., 2004; Hoogenboom, 2002). Estimation of the relative toxic potency of a complex mixture of TCDD-like HAHs using results of GC/HRMS analysis (i.e., its toxic equivalency value) involves application of established toxic equivalency factors for each measured congener of concern in a sample extract, and it is a widely accepted and internationally utilized approach (Safe, 1990; van den Berg et al., 2006). Automation of extraction and sample preparation and improvements in instrumental methods have made this analysis more rapid; however, this methodology is still not amenable or cost-effective for high-throughput routine screening analysis needed for large-scale sample studies (i.e., epidemiological studies, site contamination assessment and safety monitoring of food/feed contamination). Accordingly, numerous rapid and relatively inexpensive bioanalytical methods for use in the detection and relative quantitation of dioxin-like AhR-active chemicals present in complex mixtures extracted from a variety of matrices have been developed and validated by many laboratories (Behnisch et al., 2001a; Denison et al., 2004; Emom et al., 2008; Hahn, 2002; Whyte et al., 2004). Most bioassay systems are based on the molecular mechanism of action of dioxin and dioxin-like chemicals and take advantage of one or more aspects of the ability of these chemicals to specifically bind to and activate the AhR signal transduction pathway (Behnisch et al., 2001a; Denison et al., 2004; Hahn, 2002).

The chemically activated luciferase expression (CALUX) bioassay is one of the most commonly used screening systems, and it takes advantage of several recombinant mammalian cell lines that have been stably transfected with one of the two different AhR-responsive luciferase reporter gene plasmids we have developed that responds to TCDD and related chemicals (Behnisch et al., 2001a; Denison et al., 2004; Garrison et al., 1996; Han et al., 2004). Induction of luciferase in these recombinant CALUX cell lines occurs in a time-, dose-, and AhR-dependent and chemical-specific manner, and the amount of induced luciferase activity is directly proportional to the concentration and potency of the inducing chemical (i.e., AhR agonist) to which the cells have been exposed (Denison et al., 2004; Garrison et al., 1996; Han et al., 2004). The optimized CALUX bioassay when coupled with an appropriate sample extract cleanup method is a validated bioassay approach that can be used for accurate and reproducible detection and relative quantitation of dioxin-like chemicals in a wide variety of biological, environmental, and food/feed samples (Behnisch et al., 2001a,b; Denison et al., 2004; Vanderperren et al., 2004; Van Loco et al., 2004; Van Wouwe et al., 2004; Windal et al., 2005), and it has received regulatory certification as a validated method by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA; Method 4435; USEPA, 2008). Although the current CALUX bioassay systems have been used extensively for detection of dioxin-like chemicals in extracts of a wide variety of sample matrices, the sensitivity (minimal detection limit [MDL]) and responsiveness of the luciferase reporter gene in these cells are inadequate to allow them to be effectively used for screening of sample extracts that contain very low levels of these compounds and/or where only small amounts of sample exist for screening purposes. Accordingly, improvements in the current CALUX cell bioassay system are needed to generate screening bioassays for such applications. Here, we describe the development of amplified third-generation (G3) CALUX plasmids containing increased number of DREs, which confer greater responsiveness upon the luciferase reporter gene. Stable transfection of these plasmids into mammalian cells has generated a series of recombinant G3 CALUX cell lines with significantly improved sensitivity and a dramatically amplified reporter gene response to dioxin and dioxin-like chemicals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). TCDD was obtained from Dr S. Safe (Texas A&M University), 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran (PCDF), 3,3',4,4'-tetrachlorobiphenyl (3,3',4,4'-TCB), and 3,3',4,4',5-pentachlorobiphenyl (3,3',4,4',5-PCB) were from Accustandards (New Haven, CT), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA), Geneticin (G418) and all tissue culture media were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), Transfectol transfection reagent was from GeneChoice, Inc. (Frederick, MD), and Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Construction of G3 CALUX plasmids.

The G3 CALUX plasmids containing increasing numbers of DREs were constructed by BglII digestion of the luciferase reporter plasmid pGudLuc7.0 (Rogers and Denison, 2000), immediately upstream of the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) Δ94 promoter (which lacks glucocorticoid-responsive elements; Jones et al., 1986), and insertion of concatenated dioxin-responsive domains (DRDs), produced by self-ligation of the 480-bp BglII DRD fragments excised from the plasmid pGudLuc6.1 (Han et al., 2004), into the BglII site. Each DRD contains four AhR DNA-binding sites (DREs). Recombinants were isolated as ampicillin-resistant colonies in Escherichia coli DH5α, and identification of pGudLuc7.0 plasmids containing between 1 and 5 DRD (4 and 20 DREs) sites was confirmed by restriction digestion. The resulting plasmids were referred to as pGudLuc7.X, with ”X“ representing the number of DRDs contained within the plasmid construct and the sequence, and the orientation of each of the 480-bp DRD fragments in the DRD insert was confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis. Interestingly, although the orientation of each individual DRD found in each complete DRD concatemer fragment was identical, the entire DRD concatemer fragment was found in either orientation in the plasmid, relative to their normal orientation. The resulting plasmids were given the designations pGudLuc7.XF or pGudLuc7.XR, where X indicates the number of DRDs in the plasmid and F and R indicate the relative orientation of the DRDs compared with their normal orientation in the murine CYP1A1 promoter (i.e., forward [F] and reverse [R], respectively).

Cell culture, transient transfection, chemical treatment, and luciferase analysis.

Wild-type (wt) mouse hepatoma (Hepa1c1c7) cells were grown in alpha Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 85% humidity (Garrison et al., 1996). For transient transfections, cells were grown in six-well plates in MEM containing 10% FBS, and at about 60% confluence, the cells were transiently transfected with 2 μg of the desired G3 CALUX plasmid using Transfectol transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected cells were allowed to grow for 24 h, followed by the addition of DMSO (1% final solvent concentration) or TCDD (1nM) in DMSO and further incubation for 24 h. Afterward, the media was removed, the wells rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cells were lysed with 250 μl of cell lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), and the lysed cell samples cleared of cell debris by centrifugation in a microfuge tube. An aliquot (50 μl) of cleared lysate was transferred into a 96-well tissue culture plate and luciferase activity measured using an Anthos Lucy 2 microplate luminometer (Salzburg, Austria) following addition of 50 μl of Promega-stabilized luciferase reagent as described (Baston and Denison, 2010). Luciferase activity was normalized to the protein concentration of the cell lysate using the fluorescamine assay as described previously (Rogers and Denison, 2000).

Stable transfection, chemical treatment, and luciferase analysis.

Mouse hepatoma cells grown in a 24-well plate were cotransfected with 0.6 μg of the indicated G3 CALUX plasmid pGudLuc7.XF/R and 0.2 μg of pSV2neo (neomycin resistance vector) using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Following 24 h of growth in nonselective medium, the transfected cells were split 1–10 and replated into selective medium (MEM and 10% FBS containing 500 μg/ml of G418). The culture medium was replaced every 3 days until colonies were identified and isolated (about 2 weeks). TCDD-inducible luciferase activity of all clones was determined, and the clones with the greatest ratio of inducible to constitutive luciferase activity were selected for further analysis. In these screening and characterization studies, cell clones were plated into white, clear-bottomed 96-well tissue culture plates at 75,000 cells/well and allowed to attach for 24 h. Cells were incubated with carrier solvent DMSO (1% final solvent concentration) or the indicated concentration of TCDD for 24 h at 37°C. For studies carried out at 33°C, cells were prepared and treated as described above and incubated at 33°C (instead of 37°C) for 24 h prior to luciferase analysis. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS, followed by addition of cell lysis buffer (Promega), the plates were shaken for 20 min at room temperature to allow cell lysis and luciferase activity in each well was measured using an Anthos Lucy 2 microplate luminometer as previously described (Baston and Denison, 2010).

Preparation and analysis of sediment samples.

Three environmental sediment samples from a previous study were extracted and cleaned up to yield a hexane fraction containing PCDDs and PCDFs for analysis (Baston and Denison, 2010). The solvent containing isolated PCDD/Fs fraction was then exchanged into DMSO, and the ability of an aliquot of the fraction to induce luciferase activity in the indicated stably transfected G3 CALUX cell lines was determined as described above using an Orion microplate luminometer (Berthold, Oak Ridge, TN).

RESULTS

Generation of Recombinant G3 CALUX Vectors and Transient Transfection Studies

We constructed a series of third-generation CALUX plasmids (pGudLuc7.X) that contain between 1 and 5 DRDs or 4–20 DREs (each DRD contains 4 DREs). The number and orientation of the DRDs in each of the constructed plasmids is presented in Table 1. Interestingly, the individual 480-bp BglII DRD fragments contained within the overall 2–5 DRD concatemer fragments present in the resulting plasmids were only found in a head-to-tail orientation, even though the orientation of individual DRD could have been ligated in either orientation. However, the entire DRD concatemer occurred in both forward and reverse orientation relative to the normal orientation of the 480-bp DRD to that of the CYP1A1 promoter from which it was excised. The reason for a single orientation of the DRDs in the concatemer is not known, but it allows direct comparison of the effect of increasing DRDs on AhR-dependent gene expression because combinations of DRDs in various orientations could differentially affect AhR responsiveness.

TABLE 1.

AhR-Responsive G3 CALUX Plasmids Used in These Studies

| No. of DRDs | Plasmid name | Orientation of DRDs |

| 1 | pGudLuc7.1F | →(Forward) |

| pGudLuc7.1R | ←(Reverse) | |

| 2 | pGudLuc7.2F | →→ |

| pGudLuc7.2R | ←← | |

| 3 | pGudLuc7.3F | →→→ |

| pGudLuc7.3R | ←←← | |

| 4 | pGudLuc7.4F | →→→→ |

| pGudLuc7.4R | ←←←← | |

| 5 | pGudLuc7.5F | →→→→→ |

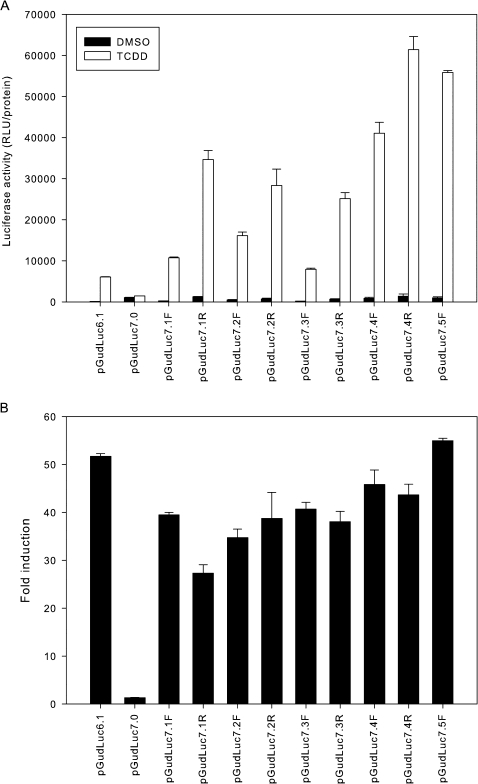

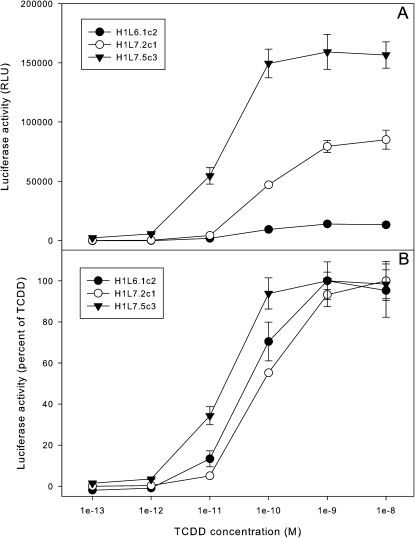

The TCDD responsiveness of each of the nine CALUX plasmids (a plasmid containing five DRDs in the reverse orientation was not obtained) was determined following transient transfection into mouse hepatoma (Hepa1c1c7) cells (Fig. 1). As expected, TCDD treatment of Hepa1c1c7 cells transfected with pGudLuc7.0 (which lacks any DRDs) failed to induce luciferase activity, whereas a significant induction of luciferase activity was observed in all cells transfected with pGudLuc7.X containing concatenated DRDs. Whereas a wide range of responsiveness was observed in the transfected cells, in general, the overall magnitude of the induction response was dramatically increased concomitant with increasing number of DRDs in the reporter plasmid. Compared with pGudLuc7.1-transfected cells, the magnitude of luciferase gene induction in pGudLuc7.5-transfected cells was about fivefold greater (Fig. 1A), whereas compared with cells transfected with pGudLuc6.1 (the second-generation [G2] AhR-responsive CALUX luciferase reporter that also contains one DRD [4DREs]; Han et al., 2004), pGudLuc7.1- and pGudLuc7.5-transfected cells had nearly 2- to 10-fold higher luciferase activity, respectively. Increasing the number of DRDs from 5 to 10 (20–40 DREs total) did not significantly increase the overall magnitude of induction (data not shown), indicating that promoter activity was maximal at 20 DREs. Although DRDs inserted in the forward direction in the reporter plasmid also conferred TCDD responsiveness onto the luciferase reporter, the magnitude of the TCDD-dependent induction response was always higher when the DRDs were in the reverse direction (Fig. 1A). Although the reason for this is not clear, it could result from orientation-dependent differences in the relative positioning of transcription factor–binding sites in the DRDs relative to the MMTV promoter. While the magnitude of the induction response was dramatically increased with increasing numbers of DRDs, luciferase activity in transfected cells incubated with DMSO was also increased to a similar degree. Thus, when the results are expressed as fold induction (Fig. 1B), the responses obtained with the G3 plasmids were not significantly greater than that with the G2 plasmid pGudLuc6.1. However, the dramatically increased activity obtained with the G3 plasmids in these transient transfection studies supports the use of these plasmids to develop improved CALUX cell lines that could detect AhR-dependent gene expression at lower TCDD/AhR agonist concentrations.

FIG. 1.

TCDD-dependent induction of luciferase activity in mouse hepatoma cells transiently transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids containing increasing numbers of DRDs. Mouse hepatoma (Hepa1c1c7) cells were transiently transfected with pGudLuc6.1 (containing 1 DRD [i.e., 4 DREs]), pGudLuc7.0 (no DRD), or third-generation plasmids pGudLuc7.X (containing between 1 and 5 DRDs [i.e., 4–20 DREs]). Cells were incubated with DMSO or 1nM TCDD for 24 h at 37°C, and the luciferase activity in cell lysates was determined as described under the “Materials and Methods” section and expressed as (A) RLUs per mg protein in the lysate or (B) fold induction. Values represent the mean ± SD of duplicate determinations and are representative of three individual experiments.

Stable Transfection of G3 CALUX Vectors

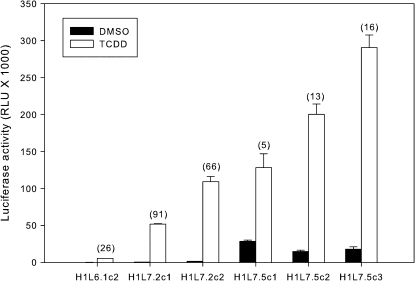

For the studies described here, mouse hepatoma cells were stably transfected with a plasmid with a large number of DRDs (pGudLuc7.5F) and a moderate number of DRDs (pGudLuc7.2R) and TCDD responsiveness of clones determined. Of the 20 clones we isolated and tested for each transfected plasmid, 5 clones (H1L7.2c1, H1L7.2c2, H1L7.5c1, H1L7.5c2, and H1L7.5c3) exhibited relatively high TCDD responsiveness (Fig. 2). Compared with the TCDD-inducible luciferase activity of ∼5000 relative light units (RLUs) using our previously described mouse hepatoma cells that contain the AhR-responsive G2 plasmid pGudLuc6.1 (with one DRD; Han et al., 2004), the magnitude of the induction response in the new stable cell clones was dramatically increased (ranging between 50,000 and 300,000 RLUs; Fig. 2). Although the overall magnitude of the luciferase induction response was dramatically increased in the cells stably transfected with the G3 plasmids containing more DRDs, the overall fold of TCDD-inducible luciferase activity was quite variable between the different clones (Fig. 2). Because the stably transfected H1L7.2c1 cells showed the greatest overall fold induction (>90-fold) and the H1L7.5c3 cells showed the greatest magnitude of the induction response by TCDD, these cell clones were selected for further characterization.

FIG. 2.

TCDD-inducible luciferase activity in CALUX cells stably transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids containing 1, 2, or 5 DRDs (4, 8, or 20 DREs, respectively). Stably transfected G2 CALUX cells (H1L6.1c2) or G3 CALUX cells containing two DRDs (H1L7.2c1, H1L7.2c2) or five DRDs (H1L7.5c1, H1L7.5c2, and H1L7.5c3) were incubated with DMSO or 1nM TCDD for 24 h at 37°C, and the luciferase activity in cell lysates was measured as described under the “Materials and Methods” section. Luciferase activity was expressed as RLUs, and the values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. The values in parenthesis above each result are the TCDD-dependent fold induction of luciferase above the DMSO control for each plasmid.

TCDD-Inducible Luciferase Activity of the Mouse Cell Clones H1L7.2c1 and H1L7.5c3

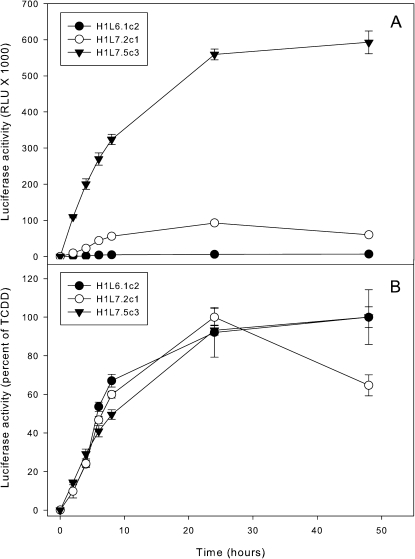

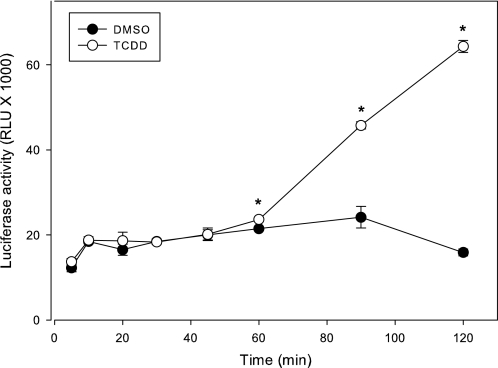

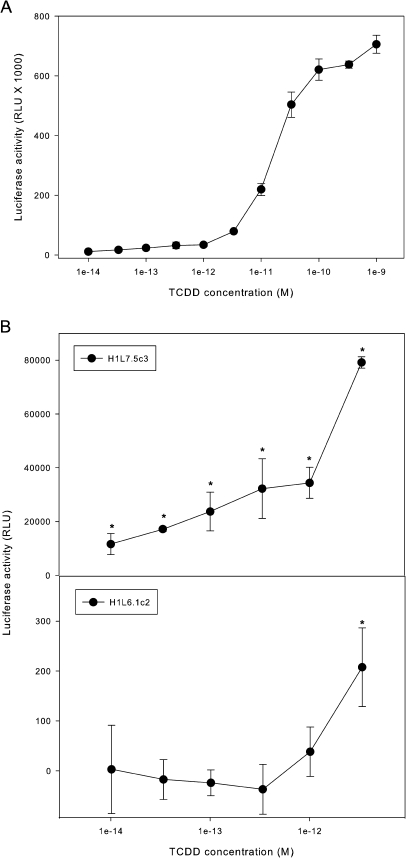

To optimize these cell lines for bioassay analysis, we examined the time course of luciferase induction in the H1L7.2c1 and H1L7.5c3 cell lines in order to determine the optimal time period for measurement of luciferase activity in treated cells (Fig. 3). In these experiments, cells were treated with DMSO or 1nM TCDD and luciferase activity determined at various time points up to 48 h after treatment. TCDD-inducible luciferase activity was detected in all three cell lines at the first time point (2 h) and progressively increased, reaching a maximum by 24 h (Fig. 3A). Expressing the time course results as a percent of the maximal activity induced in each cell line revealed that the time course of luciferase induction was essentially identical in each cell line (Fig. 3B). The decrease in luciferase activity at 48 h in the H1L7.2c1 cells in these experiments was not a consistently observed response. We selected 24 h of exposure as the standard time for bioassay analysis, although shorter times could be used. The greatly enhanced luciferase induction response observed in the H1L7.5c3 cells suggested to us that it might be able to be used for rapid detection of induced gene expression. Accordingly, we determined time course of luciferase induction in these cells starting at 5 min following TCDD addition to 2 h after treatment (Fig. 4). These experiments revealed that TCDD could stimulate a small but significant induction of luciferase activity as early as 1 h after addition to the culture.

FIG. 3.

The time course of induction of luciferase activity in G2 and G3 CALUX cell lines. Mouse hepatoma H1L6.1c2, H1L7.2c1, and H1L7.5c2 cell lines were incubated with TCDD (1nM) at 37°C for the indicated time after which luciferase activity in cell lysates was measured as described under the “Materials and Methods” section. Luciferase activity was expressed as (A) RLUs or (B) as a percent of the maximum luciferase induction by TCDD in each cell line, and the values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

FIG. 4.

The rapid time course of induction of luciferase activity in recombinant mouse hepatoma H1L7.5c3 cells. H1L7.5c3 cells were incubated with TCDD (1nM) at 37°C for the indicated time after which luciferase activity in cell lysates was measured as described under the “Materials and Methods” section. Luciferase activity was expressed as RLUs, and the values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. The asterisk indicates that the TCDD-induced luciferase activity was significantly greater (p < 0.01, Student’s t-test) than that of the DMSO control at the indicated time point.

To determine the sensitivity and overall responsiveness of the H1L7.2c1 and H1L7.5c3 G3 CALUX cell lines, the TCDD concentration dependence of luciferase induction in the cells was determined by incubation of the cells with increasing concentrations of TCDD and measurement of luciferase activity after 24 h (Fig. 5); H1L6.1c2 G2 CALUX cells were included for comparative purposes. The magnitude of the TCDD induction response for both new G3 CALUX stable cell lines was dramatically greater than that of the currently used G2 CALUX cell line H1L6.1c2, with maximal luciferase activity of ∼14,000, 86,500, and 166,000 RLUs for H1L6.1c2, H1L7.2c1, and H1L7.5c3 cells, respectively (Fig. 5A). Despite the significant difference in the overall magnitude of the luciferase induction response among the cell lines, normalization of the induction results to the activity induced in each line by 1nM TCDD revealed that they produced parallel TCDD concentration response (Fig. 5B). These results are not surprising given that the induction response is mediated by the same receptor and signaling pathway. The concentration-response curve obtained with the H1L7.5c3 G3 cell line is shifted to the left compared with that of H1L6.1c2 cells and suggests that the former cell line is more sensitive (Fig. 5B). However, statistical analysis of multiple TCDD concentration-response curves using each of the three cell lines (the range of effective concentrations at 50% of maximal response [EC50] from these analyses are indicated in Table 2) revealed no statistically significant difference in EC50 values between them.

FIG. 5.

Concentration-dependent induction of luciferase activity in G2 and G3 CALUX cell lines. Mouse hepatoma H1L6.1c2, H1L7.2c1, and H1L7.5c3 cells were incubated with TCDD at the indicated concentrations for 24 h at 37°C, and the luciferase activity in cell lysates was measured as described under the “Materials and Methods” section. Luciferase activity was expressed as (A) RLUs or (B) a percent of the maximum induction by TCDD in that cell line, with the values representing the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Bioassay Characteristics of Current CALUX-Type Recombinant Cell Lines. The Relative Potency of TCDD to Induce Luciferase (EC50) and the MDLs for TCDD in Each Cell Line Are Indicated along with the Number of DREs Present in the Luciferase Reporter Plasmid Stably Transfected into Each Cell Line

| Species | Cell line | No. of DREs | EC50 (pM) | MDL (pM) | References |

| Mouse | H1L7.5c3 (G3) | 20 | 10–16 | 0.01 | This paper |

| Mouse | H1L7.2c1 (G3) | 8 | 56–84 | 1 | This paper |

| Mouse | H1L6.1c2 (G2) | 4 | 12–50 | 1 | This paper |

| Mouse | H1L1.1c2 (G1) | 4 | 70 | 1 | This paper |

| Mouse | DR-EcoScreen | 7 | 2.8 | 0.1–1 | Takeuchi et al. (2008) |

| Guinea pig | G16L1.1c8 | 4 | ∼50 | ∼1–5 | Denison, unpublished data |

| Rat | H4IIe-Luc | 4 | 5 | 0.3–1 | Sanderson et al. (1996) |

| Rat | H4L1.1c4 | 4 | 25 | 0.5–1 | Denison, unpublished data |

| Human | HepG2-101L | 4 | 1000 | 100 | Anderson et al. (1995) |

| Human | HG2L1.1c3 | 4 | 100–500 | 0.1–1 | Denison, unpublished data |

| Human | HepG26.1 | 4 | 100 | 1–10 | Long et al. (1998) |

| Human | HKY1.7 | 4 | 200 | 10 | Yang et al. (2008) |

| Fish | RTL1.0/2.0 | 4 | 64 | 1–4 | Hahn et al. (2002) |

The main goal in the development of new CALUX bioassays was to improve its lower sensitivity for the detection of dioxin-like chemicals and other AhR agonists. Accordingly, H1L7.5c3 cells were incubated with a broader range of 11 different concentrations of TCDD (10−9 to 10−14M) and luciferase activity measured 24 h later (Fig. 6A). A more complete TCDD concentration-response curve was obtained with an EC50 of 16pM, and TCDD concentrations as low as 0.01pM could induce luciferase activity to levels significantly above background (∼10,000 RLUs above background in these experiments); the MDL for TCDD in H1L6.1c2 cells was 1pM (Han et al., 2004). Comparison of the responsiveness and sensitivity of the H1L7.5c3 G3 CALUX cells to a large number of other reported stably transfected AhR- and luciferase-based cell bioassays for dioxin-like chemicals is presented in Table 2. Although the EC50 for TCDD in H1L7.5c3 cells (16pM) is significantly higher than that reported for two of these other cell lines (2.8pM for DR-EcoScreen cells [a mouse Hepa1c1c7 cell–based assay; Takeuchi et al., 2008] and 5pM for H4IIe-Luc cells; Sanderson et al., 1996), the MDL for the H1L7.5c3 cells is at least one order of magnitude more sensitive than any other reported CALUX-type cell bioassay. Like the H1L7.5c3 cells, the DR-EcoScreen mouse hepatoma cell line (Takeuchi et al., 2008) also takes advantage of increased number of DREs in its stably transfected reporter plasmid (seven DREs) and although it is a very sensitive and responsive cell line, its overall induction response appears to occur over a 10-fold TCDD concentration range (in contrast to a 100- to 1000-fold range for H1L7.5c3 cells), thus limiting its utility for screening purposes.

FIG. 6.

Concentration-dependent induction of luciferase activity by TCDD to determine the MDL in H1L7.5c3 cells. (A) Mouse hepatoma H1L7.5c3 cells were incubated with DMSO or the indicated concentration of TCDD for 24 h at 37°C, and luciferase activity in cell lysates was measured as described under the “Materials and Methods” section. Luciferase activity was expressed as RLUs, and the values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations after subtraction of the luciferase activity obtained in cells exposed to DMSO. (B) The lower end of the TCDD concentration response curve for H1L7.5c3 cells (from panel A) is shown with an asterisk indicating those values that were significantly induced (p < 0.05) as determined by Student’s t-test. Luciferase activities from mouse hepatoma H1L6.1c2 cells exposed to the same TCDD concentrations are shown for comparative purposes.

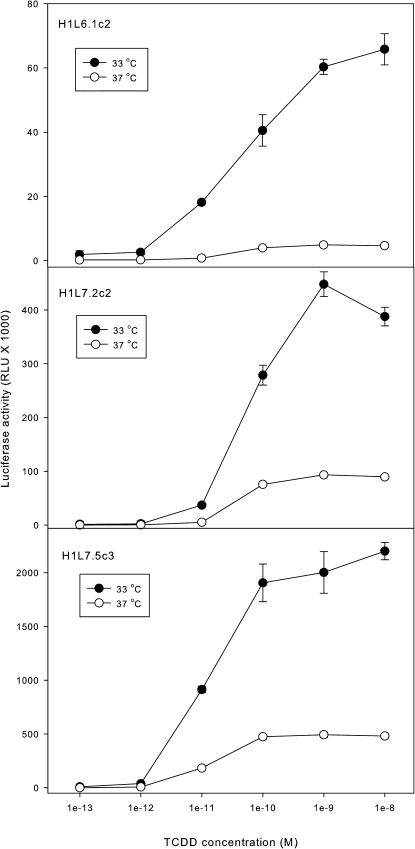

Although the new G3 CALUX cell lines are more sensitive and responsive to TCDD than our previous G2 lines, we examined whether the overall induction response and MDL could be further enhanced. We previously reported that incubation of G2 CALUX (H1L6.1c2) cells with TCDD at 33°C instead of 37°C for 24 h increased the overall induction of luciferase activity by an average of four- to fivefold (Zhao et al., 2010). The increased luciferase activity resulting from this simple change in incubation temperature appears to derive from an increase in luciferase activity (presumably due to more efficient protein folding at the lower temperature) than an overall increase in luciferase gene expression or messenger RNA levels (data not shown). To demonstrate whether a similar enhancement also occurred with the G3 CALUX cell lines, H1L6.1c2, H1L7.2c1, and H1L7.5c3 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of TCDD at 33°C or 37°C for 24 h and luciferase activity determined (Fig. 7). Similar to our previously reported results with H1L6.1c2 cells (Zhao et al., 2010), incubation of all cells at 33°C resulted in a dramatic increase in overall TCDD-inducible luciferase activity (by 4- to 10-fold); no reduction in EC50 or MDL was observed in these studies. The high level of light production from luciferase activity in individual microplate wells containing lysed TCDD-treated (1nM) H1L7.5c3 cells and luciferase substrate could easily be observed by eye in a dark room; light production from other cell lines could not be observed. Overall, the enhanced luciferase induction response observed from H1L7.5c3 cells in reduced incubation temperature conditions will allow CALUX analysis to be carried out with far fewer cells than current assays and facilitate our attempt to transition the assay from its current 96-well microplate format to higher-throughput formats (384- or 1536-well plates).

FIG. 7.

Effect of incubation temperature on the TCDD-inducible luciferase activity in G2 and G3 CALUX cell lines. Mouse hepatoma H1L6.1c2, H1L7.2c1, and H1L7.5c3 cells were incubated with the indicated concentration of TCDD at either 33°C or 37°C for 24 h, and the luciferase activity in cell lysates was measured as described under the “Materials and Methods” section. Luciferase activity was expressed as RLUs, and the values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

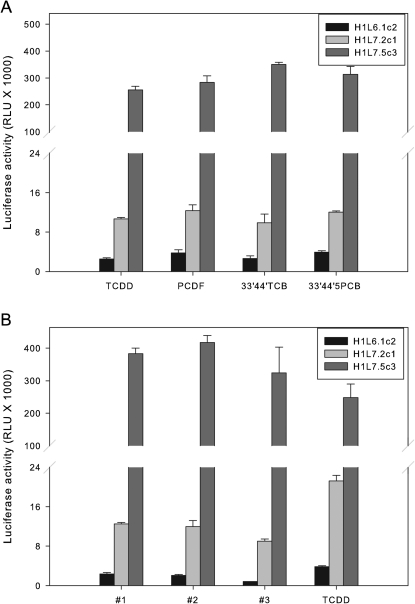

Enhanced Induction by TCDD-Like HAHs and PCDD/F Mixtures from Sediment Sample Extracts

A major application of current CALUX cell lines is their use in the detection and relative quantitation of TCDD-like HAHs in extracts of environmental matrices (Denison et al., 2004). The ability of the new G3 CALUX stable cell lines to similarly respond to TCDD and other TCDD-like HAH AhR agonists (i.e., 2,3,4,7,8-PCDF, 3,3′,4,4′-TCB, and 3,3′,4,4′,5-PCB) with a dramatically enhanced induction response, as compared with previously generated G2 CALUX bioassay (Fig. 8A), supports the use of the G3 cells for screening purposes. To demonstrate that these cells respond to complex mixtures of HAHs with the same enhanced response, we compared the ability of sediment extracts to induce luciferase activity in G2 and G3 CALUX cell lines. Sediments were collected, extracted, and cleaned up in the lab using standard procedures to remove polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, and other undesired AhR agonists (Baston and Denison, 2010; Brown et al., 2007) and the ability of the resulting PCDD/F fractions to induce luciferase activity in the H1L6.1c2, H1L7.2c1, and H1L7.5c3 recombinant cell lines determined at 24 h. TCDD was included in parallel with the environmental samples as a positive control and for comparative purposes. Similar to the results obtained above, although the PCDD/F fraction of the sediment extracts induced luciferase in all three cell lines (Fig. 8B), the magnitude of induction in the environmental extracts in the H1L7.2c1 and H1L7.5c3 G3 CALUX cell lines (10–13,000 and 300–400,000 RLUs, respectively) was dramatically greater than that observed in the H1L6.1c2 cells (1–3000 RLUs). Taken together, the above results demonstrate that the new G3 CALUX cell lines are a more sensitive and responsive cell bioassay system than the currently available G2 CALUX bioassay for detection of TCDD and TCDD-like chemicals in extracts of environmental samples.

FIG. 8.

Induction of luciferase activity by TCDD and dioxin-like HAHs and extracts of three sediment samples in G2 and G3 CALUX cell lines. Mouse hepatoma H1L6.1c2, H1L7.2c1, and H1L7.5c3 cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h with (A) 1nM TCDD, 10nM 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran (PCDF), 10 μM 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl (3,3′,4,4′-TCB), or 10nM 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl (3,3′,4,4′,5-PCB) or (B) an aliquot of the PCDD/F fraction prepared from extracts of three different sediment samples, and luciferase activity in cell lysates was measured as described under the “Materials and Methods” section. Luciferase activity was expressed as RLUs, and the values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

DISCUSSION

The CALUX cell bioassay, when coupled with appropriate sample extraction and cleanup methodology, has been successfully used for the detection and relative quantification of dioxin-like HAHs in a wide variety of biological, environmental, and food matrices, and this method has received official regulatory acceptance by the USEPA (designated as Method 4435; USEPA, 2008) for use as a validated screening bioassay for these compounds. It has also application for rapid and high-throughput sample screening and identification and characterization of AhR ligands, and we and other groups have used these cell-based bioassay methods to identify novel synthetic and/or naturally occurring AhR agonists and antagonists (Bohonowych et al., 2008; Boitano et al., 2010; DiNatale et al., 2010; Jeuken et al., 2003; Knockaert et al., 2004; Seidel et al., 2001). In addition, the CALUX cell bioassay has been used in combination with bioassay-directed fractionation strategies to isolate and identify an endogenous AhR ligand present in pig lung (Song et al., 2002) as well as toxic and nontoxic AhR agonists present in complex mixtures of environmental samples (Behnisch et al., 2001b; Denison et al., 2004; Takigami et al., 2010). While numerous CALUX-type bioassay approaches have been described that are adequate for the screening of many sample matrices (Table 2), current bioassays are not sensitive enough when screening samples containing very low levels of AhR-active ligands or when the amount of sample is limiting (i.e., blood/serum samples). The significant variations observed in the overall responsiveness, EC50s, and MDLs among all known CALUX-type bioassays result from many differences including variation in TCDD affinity for the AhR and transcription machinery in the different cell types; differences in the sequence, numbers, and orientations of DREs in the AhR-responsive plasmids used to generate each bioassay; and the number of plasmids and their site(s) of integration into the genome of each cell line (Bank et al., 1992; Denison et al., 2004; Fisher et al., 1990; Pilbrough et al., 2009; Schimke et al., 1985; Wurtele et al., 2003). Thus, generation of an optimal cell-based screening bioassay for dioxin-like HAHs requires consideration of many factors and substantial screening of stably transfected cell lines to identify the cell clone(s) with the desired characteristics. Accordingly, to develop a more sensitive and/or more responsive CALUX bioassay for use in screening of these low-level/-volume samples, several novel approaches need to be considered in which to enhance or amplify current cell bioassays including increasing the number and/or affinity of AhRs in the cells used in the bioassay as well as improving the reporter plasmids. Other approaches include amplification of the number of AhR-responsive plasmids contained within a given cell and increasing the number of DREs within the CALUX reporter vector. In this report, we describe the application of the latter approach to enhance the AhR-based CALUX bioassay and we have successfully generated a series of AhR-responsive luciferase reporter plasmids (with up to 20 DREs) and demonstrated its advantages in the screening of environmental sample extracts for dioxin-like activity. These plasmids and the resulting stably transfected cell lines exhibit improved bioassay characteristics, including increased assay sensitivity, lower limits of detection, and dramatically enhanced reporter gene expression compared with existing CALUX cell bioassays.

The overall magnitude of induction and sensitivity of response increased progressively as the number of DRDs increased from 1 to 5 (4–20 DREs); however, increasing the number of DRDs further to 10 (i.e., 40 DREs) did not further increase the sensitivity and response (data not shown), suggesting that the number of AhRs or transcription factors became limited and/or the transcriptional activity of the promoter was maximal. Although attempts to amplify nuclear receptor–based reporter assays with large numbers of responsive elements have not been successfully reported, the successful generation of an amplified AhR-based bioassay could result from several key aspects of our approach. First, the mouse hepatoma (Hepa1c1c7) cell line was optimal for such an enhanced bioassay because of its high degree of responsiveness to TCDD and related chemicals and unusually high concentration of AhR complexes in these cells (Holmes and Pollenz, 1997). Additionally, incorporation of a large number of DREs into the luciferase reporter gene plasmid was not based on concatenating many small DRE-containing oligonucleotides but by concatenating larger DNA fragments (∼480 bp) that contained four DREs distributed throughout the fragment (Han et al., 2004). In this way, there was likely little interference with receptors bound to adjacent sites as would occur with concatenated oligonucleotides containing closely spaced binding sites. Additionally, the 480-bp DRD used in these plasmids might also contain other transcription factor–binding sites that can contribute to the increased responsiveness. Another likely factor contributing to the successful development of the G3 CALUX bioassay is the apparently high transcriptional activation capacity of the MMTV Δ94 promoter present in these plasmids that can function far faster and/or more efficiently than what has been observed with plasmids like pGudLuc6.1, which contain only one DRD (four DREs; Han et al., 2004). Not only was the overall magnitude of the luciferase induction response greater with the G3 CALUX cell bioassays, compared with the G2 CALUX (H1L6.1c2) cells, but the detection limit and sensitivity of the G3 CALUX bioassay (specifically that of the H1L7.5c3 cells) were lower by a factor of 10- to 100-fold. The primary contributor to the lower TCDD detection limit of the H1L7.5c3 cells compared with that of the H1L6.1c2 cells is likely due to the high number of DREs in the plasmid present in the H1L7.5c3 cells that facilitates activation of luciferase gene expression at very low levels of activated nuclear AhR; however, additional factors must be involved because the number of DREs is only increased fivefold, whereas the overall increase in sensitivity and response is much greater.

A primary attribute of the newly developed G3 CALUX vectors and stable cell lines is their dramatically greater luciferase activity observed at very low TCDD concentrations. The overall activity in the H1L7.5c3 cells was significantly above background (e.g., 10,000–30,000 RLUs higher than that in DMSO-treated cells) at 0.01–1pM TCDD, resulting in a significantly lower MDL for the G3 CALUX bioassay (Table 2) when compared with current CALUX-type cell bioassays, where results were indistinguishable from background at these same TCDD concentrations (Fig. 6B). However, even with these lower limits of detection and amplified responses, the new G3 CALUX stably transfected cell lines have significantly higher background luciferase activity, compared with that of the G2 CALUX luciferase vectors. Although the overall level of TCDD-inducible luciferase activity is dramatically enhanced, the concomitantly elevated background activity results in relatively low fold induction values (see Figs. 1 and 2). Because the G2 CALUX cell line H1L6.1c2 (containing the plasmid pGudLuc6.1) had relatively low background luciferase activity, compared with newly developed G3 CALUX vectors and stable cell lines, and this vector contains an additional 1100-bp MMTV fragment that might contain transcription terminator sequences immediately upstream of the DRD (Han et al., 2004; Rushing and Denison, 2002), we considered that the insertion of this MMTV fragment adjacent to the DRDs in the pGudLuc7.X vectors would decrease the background luciferase activity. Although the MMTV fragment was inserted immediately upstream of the DRDs in the pGudLuc7.X plasmids (making the pGudLuc8.X plasmid series), preliminary transient transfection experiments with these vectors in Hepa1c1c7 cells actually resulted in reduced TCDD-inducible luciferase activity, with no significant reduction in background luciferase activity compared with the respective pGudLuc7.X vector (data not shown). Another possible contributor to the elevated background luciferase activity observed in the H1L7.5c3 cells might be endogenous AhR agonists present in the serum included in the tissue culture media. We recently observed that treatment of cells with DMSO (dissolved in fresh media/serum) or just feeding of the cells with fresh media/serum resulted in a modest time-dependent induction of luciferase activity that peaked at 6–8 h and declined over 48 h to a value approximately one-third of that observed at 8 h (data not shown). Although several previous studies have suggested the presence of endogenous AhR agonists in serum that can stimulate transient activation of the AhR (Adachi et al., 2001; Feng et al., 2002; Schlezinger et al., 2010), we have never observed this with our previous CALUX cell lines. However, the low level of AhR activation by serum may now be detectable given the significantly improved sensitivity and response of the H1L7.5c1 cells. Lower background levels would be obtained in these assays if CALUX cells were allowed to grow in the microplate for at least 48 h after plating and if chemicals or extracts to be tested were dissolved in media depleted of these endogenous agonists (i.e., media removed from CALUX cells incubated for at least 48 h). Together, these modifications of the bioassay should result in lower background luciferase activity.

The increased responsiveness and lower MDL of the G3 CALUX bioassay provide us with several new avenues in which to expand both the format of the bioassay and its applications. The dramatically increased induction response to TCDD (and other AhR agonists [data not shown]) means that fewer cells are required per well for the detection of AhR activation and this will allow the assay to be carried out in a 384- and 1536-well microplate formats, thus further reducing sample and reagent costs and increasing sample throughput. These improvements, coupled with the increased sensitivity of the G3 bioassay, will facilitate screening analysis of samples containing low levels of dioxin-like chemicals (such as those commonly encountered with food and feed samples), those where the sample matrices for analysis are very limiting (e.g., large epidemiology studies) as well as large chemical libraries used to identify novel AhR agonists and antagonists. Stable transfection of these vectors into AhR-containing continuous cell lines from a variety of species (rat, human, guinea pig, fish, and others) will result in the generation of highly sensitive species-specific bioassay systems for AhR agonist and help to examine species differences in TCDD responsiveness. Additional enhancement and optimization of the G3 CALUX vectors, cell lines, and assay conditions, such as those described by Zhao et al. (2010), will allow us to further improve the new CALUX bioassays and expand their applications.

FUNDING

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES012498, R01ES007685, P42ES04699 [Superfund Basic Research Grant] to M.S.D.); Chinese Academy of Sciences Key Program of Knowledge Innovation (KZCX2-EW-411 to B.Z.); California Agricultural Experiment Station; American taxpayers; Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants to T.T.; Japan Food Hygiene Association Grant for Promoted Project of Research on Risk of Chemical Substances (fiscal 2005) to T.T.

References

- Adachi J, Mori Y, Matsui S, Takigami H, Fujino J, Kitagawa H, Miller CA, 3rd, Kato T, Saeki K, Matsuda T. Indirubin and indigo are potent aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands present in human urine. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:31475–31478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JW, Rossi SS, Tukey RH, Vu T, Quattrochi LC. A biomarker, P450 RGS, for assessing the induction potential of environmental samples. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1995;14:1159–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Bank PA, Yao EF, Phelps CL, Harper PA, Denison MS. Species-specific binding of transformed Ah receptor to a dioxin responsive transcriptional enhancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;228:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(92)90016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baston DS, Denison MS. Considerations for potency equivalent calculations in the Ah receptor-based CALUX bioassay: normalization of superinduction results for improved sample potency estimation. Talanta. 2010;83:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnisch PA, Hosoe K, Sakai S. Bioanalytical screening methods for dioxins and dioxin-like compounds, a review of bioassay/biomarker technology. Environ. Int. 2001a;27:413–439. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(01)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnisch PA, Hosoe K, Sakai S. Combinatorial bio/chemical analysis of dioxin-like compounds in waste recycling, feed/food, humans/wildlife and the environment. Environ. Int. 2001b;27:495–519. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(01)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohonowych JES, Zhao B, Timme-Laragy A, Jung D, Di Giulio RT, Denison MS. Newspapers and newspaper ink contain agonists for the Ah receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;98:99–110. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitano AE, Wang J, Romeo R, Bouchez LC, Parker AE, Sutton SE, Walker JR, Flaveny CA, Perdew GH, Denison MS, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonists promote the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2010;329:1345–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1191536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DJ, Orelien J, Gordon JD, Chu AC, Chu MD, Nakamura M, Handa H, Kayama F, Denison MS, Clark GC. Mathematical model developed for environmental samples: prediction of GC/MS dioxin TEQ from XDS-CALUX bioassay data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:4354–4360. doi: 10.1021/es062602+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison MS, Phelan D, Elferink CJ. The Ah receptor signal transduction pathway. In: Denison MS, Helferich WG, editors. Toxicant-Receptor Interactions. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis; 1998. pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Denison MS, Seidel SD, Rogers WJ, Ziccardi M, Winter GM, Heath-Pagliuso S. Natural and synthetic ligands for the Ah receptor. In: Puga A, Wallace KB, editors. Molecular Biology Approaches to Toxicology. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis; 1998. pp. 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Denison MS, Zhao B, Baston DS, Clark GC, Murata H, Han D-H. Recombinant cell bioassay systems for the detection and relative quantitation of halogenated dioxins and related chemicals. Talanta. 2004;63:1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNatale BC, Murray IA, Schroeder JC, Flaveny CA, Lahoti TS, Laurenzana EM, Omiecinski CJ, Perdew GH. Kynurenic acid is a potent endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that synergistically induces interleukin-6 in the presence of inflammatory signaling. Toxicol. Sci. 2010;115:89–97. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emom JM, Chuang JC, Lordo RA, Schrock ME, Nichkova M, Gee S, Hammock BD. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for determination of dioxins in contaminated sediment and soil samples. Chemosphere. 2008;72:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q, Kumagi T, Nakamura Y, Uchida K, Osawa T. Induction of cytochrome P4501A1 by autoclavable culture medium change in HepG2 cells. Xenobiotica. 2002;31:1033–1043. doi: 10.1080/0049825021000012583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JM, Wu L, Denison MS, Whitlock JP., Jr Organization and function of a dioxin-responsive enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:9767–9681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness SG, Whelan F. The pleiotropy of dioxin toxicity—xenobiotic misappropriation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor's alternative physiological roles. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;124:336–354. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison PM, Tullis K, Aarts JMMJG, Brouwer A, Giesy JP, Denison MS. Species-specific recombinant cell lines as bioassay systems for the detection of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-like chemicals. Fund. Appl. Toxicol. 1996;30:194–203. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn ME. Biomarkers and bioassays for detecting dioxin-like compounds in the marine environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2002;289:49–69. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(01)01016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D-H, Nagy SR, Denison MS. Comparison of recombinant cell bioassays for the detection of Ah receptor agonists. Biofactors. 2004;20:11–22. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson O. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1995;35:307–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JL, Pollenz RS. Determination of aryl-hydrocarbon receptor, nuclear translocator-protein concentration and subcellular localization in hepatic and non-hepatic cell culture lines: development of quantitative Western blotting protocols for calculation of aryl-hydrocarbon receptor and aryl-hydrocarbon receptor nuclear-translocator protein in total cell lysates. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:202–211. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenboom R. The combined use of the CALUX bioassay and the HRGCHRMS method for the detection of novel dioxin sources and new dioxin-like compounds. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2002;9:304–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02987571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Program on Chemical Safety (IPCS) Polybrominated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins and Dibenzofurans, Environmental Health Criteria 205. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jeuken A, Keser BJG, Khan E, Brouwer A, Koeman J, Denison MS. Activation of the Ah receptor by extracts of dietary herbal supplements, vegetables, and fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:5478–5487. doi: 10.1021/jf030252u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PBC, Durrin LK, Galeazzi DR, Whitlock JP., Jr Control of cytochrome P1-450 gene expression: analysis of a dioxin-responsive enhancer system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986;83:2802–2806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knockaert M, Blondel M, Bach S, Leost M, Elbi C, Hager GL, Nagy SR, Han D, Denison MS, French M, et al. Independent actions on cyclin-dependent kinases and aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediate the antiproliferative effects of indirubins. Oncogene. 2004;23:4400–4412. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long WP, Pray-Grant M, Tsai JC, Perdew GH. Protein kinase C activity is required for aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway-mediated signal transduction. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:691–700. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilbrough W, Munro TP, Gray P. Intraclonal protein expression heterogeneity in recombinant CHO cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JM, Denison MS. Recombinant cell bioassays for endocrine disruptors: development of a stably transfected human ovarian cell line for the detection of estrogenic and anti-estrogenic chemicals. In Vitro Mol. Toxicol. 2000;2000(13):67–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushing S R, Denison M S. The silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT) can interact with the Ah receptor but fails to Repress Ah receptor-dependent gene expression. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;403:189–201. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs), dibenzofurans (PCDFs), and related compounds: environmental and mechanistic considerations which support the development of toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1990;21:51–88. doi: 10.3109/10408449009089873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson J, Aarts JMMJG, Brouwer A, Froese KL, Denison MS, Giesy JP. Comparison of Ah receptor-mediated luciferase and ethoxyresorufin O-deethylase induction in H4IIE cells: implications for their use as bioanalytical tools for the detection of polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1996;137:316–325. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimke RT, Hill A, Johnston RN. Methotrexate resistance and gene amplification—an experimental model for the generation of cellular heterogeneity. Br. J. Cancer. 1985;51:459–465. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1985.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlezinger JJ, Bernard PL, Haas A, Grandjean P, Weihe P, Sherr DH. Direct assessment of cumulative aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist activity in sera from experimentally exposed mice and environmentally exposed humans. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:693–698. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel SD, Winters GM, Rogers WJ, Ziccardi MH, Li V, Keser B, Denison MS. Activation of the Ah receptor signaling pathway by prostaglandins. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2001;15:187–196. doi: 10.1002/jbt.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Clagett-Dame M, Peterson RE, Hahn ME, Westler WM, Sicinski RR, DeLuca HF. A ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor isolated from lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:14694–14699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232562899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi S, Iida M, Yabushita H, Matsuda T, Kojima H. In vitro screening for aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonistic activity in 200 pesticides using a highly sensitive reporter cell line, DR-EcoScreen cells, and in vivo mouse liver cytochrome P450-1A induction by propanil, diuron and linuron. Chemosphere. 2008;74:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takigami H, Suzuki G, Sakai S. Screening of dioxin-like compounds in bio-composts and their materials: chemical analysis and fractionation-directed evaluation of AhR ligand activities using an in vitro bioassay. J. Environ. Monit. 2010;12:2080–2087. doi: 10.1039/c0em00200c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Method for Toxic Equivalents (TEQs) Determinations for Dioxin-Like Chemical Activity with the CALUX Bioassay, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. 2008. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/osw/hazard/testmethods/pdfs/4435.pdf, Accessed August 5, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg M, Birnbaum LS, Denison M, De Vito M, Farland W, Feeley M, Fiedler H, Hakansson H, Hanberg A, Haws L, et al. The 2005 World Health Organization re-evaluation of human and mammalian toxic equivalency factors for dioxins and dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;93:223–241. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderperren H, Van Wouwe N, Behets S, Windahl I, Van Overmeire I, Fontaine A. TEQ-value determinations of animal feed; emphasis on the CALUX bioassay validation. Talanta. 2004;63:1277–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loco J, Van Leeuwen SP, Roos P, Carbonnelle S, de Boer J, Goeyens L, Beernaert H. The international validation of bio- and chemical-analytical screening methods for dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs: the DIFFERENCE project rounds 1 and 2. Talanta. 2004;63:1169–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wouwe N, Windal I, Vanderperren H, Eppe G, Xhroute C, Massart AC, Debacker N, Sasse A, Baeyens W, De Pauw E, et al. Validation of the CALUX bioassay for PCDD/F analyses in human blood plasma and comparison with GC-HRMS. Talanta. 2004;63:1157–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte JJ, Schmitt CJ, Tillitt DE. The H4IIe cell bioassay as an indicator of dioxin-like chemicals in wildlife and the environment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2004;34:1–83. doi: 10.1080/10408440490265193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windal I, Van Wouse N, Eppe G, Xhrouet C, Debacker V, Baeyens W, De Pauw E, Goeyens L. Validation and interpretation of CALUX as a tool for the estimation of dioxin-like activity in marine biological matrixes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:1741–1748. doi: 10.1021/es049182d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele H, Kittle KCE, Chartrand P. Illegitimate DNA integration in mammalian cells. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1791–1799. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J-H, Lee H-G, Park K-Y. Development of human dermal epithelial cell-based bioassay for the dioxins. Chemosphere. 2008;72:1188–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Baston DS, Khan E, Sorrentino C, Denison MS. Enhancing the response of CALUX and CAFLUX cell bioassay for quantitative detection of dioxin-like compounds. Sci. China Chem. 2010;53:1010–1016. doi: 10.1007/s11426-010-0142-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]