INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States and is often acquired soon after onset of sexual activity.1 HPV types 16 and 18 are causally linked to approximately 70% of cervical cancer cases2; HPV 6 and 11 cause 90% of anogenital warts. The quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine protects against infection from HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18.3 It was recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in June 2006 for routine 3-dose vaccination of girls aged 11–12.4 The vaccination series can be initiated by girls beginning at age 9; catch-up vaccination is recommended for girls and young women aged 13–26 who have not been previously vaccinated or who have not completed the full series. In 2009, the ACIP made similar recommendations for the bivalent HPV vaccine, which protects against infection from HPV types 16 and 18.5 The target age for HPV vaccination is 11–12 years to ensure protection at an earlier age, prior to sexual debut.4

Monitoring HPV vaccine uptake allows public health practitioners to identify unvaccinated populations and to develop targeted interventions to increase vaccine coverage. Depending on uptake patterns, HPV vaccine has the potential to reduce existing disparities in cervical cancer, including a higher incidence and mortality among blacks, Hispanics, women of limited income, and women who do not access cervical cancer screening.6–8 Although several analyses have examined HPV vaccine coverage in the United States, most are limited surveys9–18, with few that are national in scope.15, 19, 20 In this study, we use the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to (1) examine quadrivalent HPV vaccine uptake 1–2 years after vaccine licensure among preadolescent and adolescent girls in the United States, (2) identify sociodemographic factors and preventive health behaviors associated with vaccine uptake, and (3) describe parental reasons for not intending to have their daughter vaccinated. We hypothesize that older girls are more likely to be vaccinated against HPV than younger girls. Our study along with the accompanying paper by Anhang Price, et al provides a comprehensive examination of national HPV vaccine uptake for females 9 to 26 years old, the full age range for which the vaccine is recommended.21

METHODS

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

The NHIS is an annual multi-purpose in-person health survey of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The sampling strategy uses a multistage area probability design and oversamples for black, Hispanic, and Asian populations. From each family, one sample adult and one sample child (<18 years) are randomly selected. In the NHIS Child Module, sample children do not self-report; instead a parent or parent proxy answers questions on the sample child’s behalf. Details on survey design are available elsewhere. 22 The 2008 NHIS child supplement was administered continuously from January to December and included a sample of 8815 children younger than 18. The response rate for the 2008 child module was 72.3%. The HPV questions were administered to all families with girls aged 8–17. We restricted our analysis to 2205 parents or parent proxies of girls aged 9–17 who were age-eligible for HPV vaccination at the time of the survey. 4 The vast majority of respondents (93.1%) were parents.

Measures

The NHIS child supplement contained seven questions on HPV vaccine asking about the parent’s awareness of the vaccine, receipt of the vaccine by the adolescent, the number of doses received, and among the unvaccinated, parental intention to vaccinate if the vaccine was recommended by a doctor. Parents who did not intend to have their daughter vaccinated were asked their main reason for not vaccinating their daughters; open-ended responses were given and categorized into one of 13 response categories based on previous rounds of survey research (does not need vaccine, not sexually active, too expensive, too young for vaccine, doctor didn’t recommend it, worried about safety of vaccine, don’t know where to get vaccine, my spouse/family member is against it, don’t know enough about the vaccine, already has HPV, other, refused, don’t know). Parents who did not vaccinate their daughters but were interested in vaccination were asked whether they would vaccinate if the cost, including three HPV doses, administrative costs, and clinic visit, was in the range of $360–$500. Parents of unvaccinated girls who would not pay that amount or thought that the vaccine was too expensive were asked whether they would vaccinate their child if the vaccine was free or cost much less. Additional measures in the NHIS included sociodemographic characteristics and preventive health behaviors, such as whether the child had a well-child check-up, dental exam, or flu shot in the past 12 months.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses for HPV vaccine uptake (receipt of vaccine doses 1, 2 and 3), including estimates of proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CI), were evaluated by age group at time of interview: prior to routine recommendation (9–10 years), target (11–12 years), and catch up (13–17 years). Intention to vaccinate if the child’s physician recommended the vaccine and parental reasons for not vaccinating were examined for girls aged 9–17. We also stratified parents’ willingness to pay for or receive free HPV vaccines by child’s insurance coverage. In bivariate analyses, differences in factors associated with HPV vaccine initiation (receipt of 1 vaccine dose) among girls aged 11–17, including sociodemographic characteristics, preventive health behaviors, and parental HPV vaccine familiarity, were evaluated using chi-square statistics. Girls aged 9–10 were not included in the bivariate or multivariate analyses of vaccination receipt due to small sample numbers of vaccinated girls in this age group (n = 11). Records with missing, refused, or don’t know responses for HPV initiation (n = 56, 3.1%) were not included in the bivariate and multivariate analyses.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association between sociodemographic characteristics, preventive health behaviors, and HPV vaccine parental familiarity with HPV vaccine initiation for girls aged 11–17. We eliminated variables from the model by using the backwards selection regression method, using a P-value approach (successively eliminating the variable with the largest P-value), to develop our final model and at the same time assessed changes in covariates which remained in the model. Region and race were included in all models; otherwise, we retained in the final model variables with P-value <0.10. To facilitate interpretation of comparison of vaccine initiation across variables’ categories, we computed and presented adjusted percentages (predicted margins), which are derived from the logistic regression model. 23 Overall associations were assessed with Wald F statistic, and we used general linear contrasts (pairwise comparisons) of the percentages to test differences between categories within each adjusted variable.

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 9.2 and SUDAAN release 10 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC). To generalize the results to the population of girls aged 9–17, sampling weights were assigned to each survey respondent. These weights were included in data files obtained from NCHS and account for stratified sampling survey design and nonresponse. We also calculated the relative standard errors as (standard error/estimated percentage) ×100 for each estimated percentage. An estimated percentage is considered unstable if its relative standard error is >30%; an unstable estimate should be interpreted cautiously. Studies such as this that use deidentified, publicly available data do not require Centers for Disease Control institutional review board approval.

RESULTS

HPV Vaccine Uptake

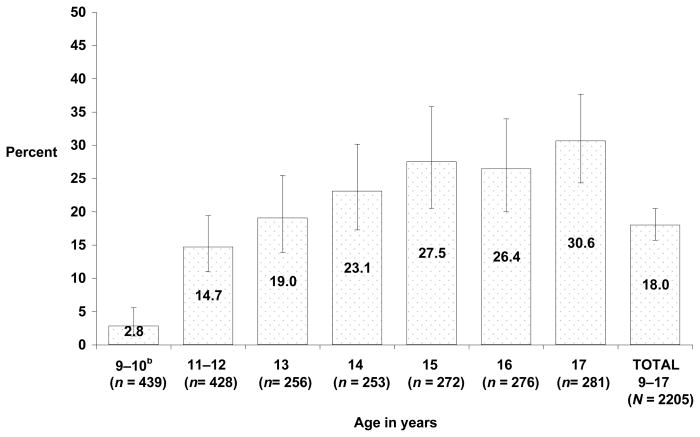

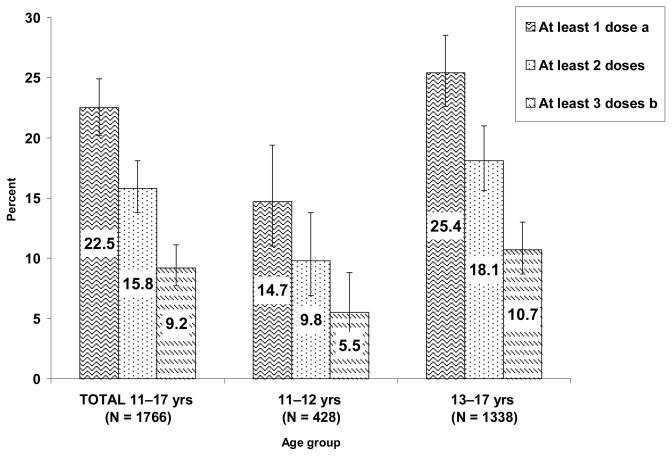

Overall, 2.8% of 9–10 year olds, 14.7% of 11–12 year olds, and 25.4% of 13–17 year olds had received at least one dose of HPV vaccine (Figures 1a/1b). We observed increased vaccine uptake with increased age (Figure 1a). Of the total number of girls surveyed, an estimated 5.5% of 11–12 year olds and 10.7% of 13–17 year olds had completed all 3 doses (Figure 1b). Data for 2 and 3 dose uptake in 9–10 year old girls could not be presented because of small sample sizes.

Figure 1a .

Quadrivalent HPV vaccine initiationa among girls aged 9–17 years, by age National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2008

a Initiation refers to receipt of 1 dose of the vaccine.

bEstimate for girls aged 9–10 years are unstable and should be interpreted with caution.

Percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 9–17 years.

Missing data (total <1%) and refused or don’t know (total = 2.2%) are included in percentage calculations.

Error bars are 95% CI around the estimated percentage.

Figure 1b .

Estimated quadrivalent HPV vaccination uptake among girls aged 11–17 years, by age group and number of doses National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2008

aNumber of doses received is unknown for 12 girls (aged 11–17 years) with reported vaccine initiation; therefore it was included only in the >= 1 dose category.

bIncludes 4 reports of 4 vaccine doses received and 1 report of 5 doses received.

Percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 11–17 years.

Missing data and refused to answer or don’t know are included in the analysis.

Error bars are 95% CI around the estimated percentage.

Uptake of doses 2 and 3 for girls aged 9–10 years not reported due to small unweighted sample sizes.

Characteristics of Girls and Households Associated with HPV Vaccine Initiation

Bivariate analysis showed that there was no significant difference in HPV vaccine initiation between non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks or Hispanics; non-Hispanic Asian girls had a significantly lower vaccine initiation (7.4%) than all other race/ethnicity groups (p<0.01) (Table 1). Children with public or private insurance coverage had significantly greater vaccine initiation compared to children without insurance (p<0.001). Preventive health behaviors and parental familiarity with the HPV vaccine were also strongly associated with higher rates of vaccine initiation (p<0.001 respectively).

Table 1.

Factors associated with quadrivalent HPV vaccine initiation among girls aged 11–17 years National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2008

| Sample sizea | Unadjusted percentages %b (95% CI) |

P-valuec | Adjusted percentages %d (95% CI) |

P-valuee | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ** | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 812 | 24.8 (21.6–28.2) | 22.7 (19.8–25.9) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 293 | 21.2 (16.1–27.3) | 24.2 (18.6–30.8) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 95 | 7.4 (4.1–13.1) | 10.4 (5.2–19.9) | ||

| Hispanic | 436 | 21.4 (16.4–27.5) | 26.6 (21.2–32.7) | ||

| Otherf | 74 | 30.0 (18.4–44.7) | 24.7 (15.5–37.1) | ||

| Region | * | ||||

| Northeast | 303 | 26.3 (21.2–32.0) | 24.6 (20.9–28.9) | ||

| Midwest | 365 | 27.9 (23.2–33.2) | 26.4 (22.1–31.2) | ||

| South | 612 | 19.9 (16.4–23.8) | 20.3 (17.0–24.0) | ||

| West | 430 | 20.7 (15.6–26.9) | 22.6 (17.2–29.1) | ||

| Highest education level completed by parent | * | ||||

| Less than high school | 187 | 21.7 (14.9–30.5) | 33.1 (24.8–42.6) | ||

| High school graduate or GED | 403 | 17.9 (13.8–22.9) | 18.3 (14.2–23.4) | ||

| More than high school | 1119 | 25.1 (22.1–28.4) | 23.6 (20.9–26.6) | ||

| Family poverty threshold | |||||

| Below poverty | 227 | 26.6 (20.1–34.2) | Not included in final model | ||

| At or above poverty, < 200% poverty | 320 | 21.6 (16.4–27.9) | |||

| ≥ 200% poverty | 949 | 23.4 (20.3–26.7) | |||

| Unknown | 214 | 21.1 (14.4–29.6) | |||

| Child’s insurance coverage | *** | ||||

| No insurance | 198 | 11.5 (6.9–18.4) | |||

| Public insurance | 422 | 27.7 (22.5–33.7) | |||

| Private insurance | 1082 | 23.4 (20.3–26.7) | |||

| Had a well-child check-up in past 12 months | *** | *** | |||

| Yes | 1143 | 28.8 (25.6–32.2) | 26.1 (23.2–29.2) | ||

| No | 557 | 11.1 (8.1–14.9) | 14.8 (11.0–19.6) | ||

| Has had dental exam in last 12 months | *** | ||||

| Yes | 1399 | 25.1 (22.5–28.0) | 23.9 (21.3–26.6) | ||

| No | 296 | 12.9 (9.0–18.3) | 18.1 (13.3–24.0) | ||

| Has had a flu shot in the last 12 months | *** | *** | |||

| Yes | 328 | 45.2 (38.3–52.2) | 39.1 (33.5–45.0) | ||

| No | 1358 | 17.7 (15.4–20.3) | 18.7 (16.3–21.4) | ||

| Parent familiarity with HPV vaccine | *** | *** | |||

| Yes | 1124 | 33.0 (29.9–36.4) | 31.8 (28.7–35.0) | ||

| No | 582 | 2.1 (1.0–4.1) | 2.4 (1.1–4.8) | ||

These numbers are denominators for the unadjusted percentages. Total N for each variable does not always equal 1710 due to missing data, which were < 5%.

Percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 11–17 years.

P-value calculated with chi-square test for independence using only HPV vaccine initiation = yes or no No star – Not significant,

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001.

Results are based on 1667 responses in the analysis. Percentages are adjusted to all other variables in model (race/ethnicity, region, highest education level completed, well-child check in past year, dental exam in past year, flu shot in past year, and parent familiarity with HPV vaccine). Percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 11–17 years.

P-values were based on a global Wald F test for association using a logistic regression model.

Other included Non-Hispanic American Indian Alaska Native, not releasable, and multiracial.

After adjusting for all other variables in the model, the overall differences in HPV vaccine initiation by race/ethnicity were no longer statistically significant (Table 1). However, in pairwise contrasts (data not shown), non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black girls had significantly higher vaccine initiation than non-Hispanic Asian girls (p<0.01). Parents with less than high school education were significantly more likely to vaccinate their daughter than parents who are high school graduates or have a GED (p<0.01) or have more than high-school education (p<0.05). Having a well-child check or a flu shot in the past year were significantly associated with vaccine initiation (p<0.001). Parent familiarity with the vaccine continued to be strongly associated with vaccine initiation (p<0.001).

Reasons for Not Vaccinating

Table 2 examines reasons for not vaccinating among the parents of daughters aged 9–17. Overall, the most common reasons reported by these parents for not vaccinating their daughters were that their daughter did not need the vaccine (21.5%) and that they had insufficient information about the vaccine (17.7%). Parents of older girls more often cited that their daughters were not sexually active as a reason, while concerns that their daughter was too young for the vaccine diminished as age increased. Among the parents of unvaccinated daughters , 47% said that they would not vaccinate their daughter if recommended by a doctor and 14% did not know (data not shown). We found no significant differences by age group in intent to receive the vaccine after a doctor recommendation (data not shown).

Table 2.

Parentala reasons for not vaccinating girls aged 9–17 years, by age National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2008

| 9–10 years | 11–12 years | 13–17 years | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 260) | (n= 220) | (n= 625) | (n = 1105) | |

| %b | %b | %b | %b | |

| Does not need vaccine | 22.6 | 22.4 | 20.4 | 21.5 |

| Does not know enough about vaccine | 15.0 | 17.6 | 19.0 | 17.7 |

| Not sexually active | 10.2 | 11.6 | 18.5 | 14.7 |

| Worried about safety of vaccine | 14.3 | 17.1 | 13.5 | 14.5 |

| Too young for vaccine | 19.0 | 13.8 | 3.6 | 9.9 |

| Doctor did not recommend it | ---c | ---c | 5.2 | 5.5 |

| Too expensive | ---c | ---c | ---c | 1.6 |

| Otherd | 5.3 | 8.6 | 12.4 | 9.7 |

| Do not know | 6.2 | ---c | 5.2 | 4.8 |

Sample of parents whose daughter was not vaccinated and who did not intend to vaccinate their daughter against HPV if the doctor recommended it.

Percentages are weighted to the population of girls 9–17 years of age.

Estimate not reported because the relative standard error was > 30% or small unweighted sample size.

Other includes the following response categories: Do not know where to get vaccine, My spouse/family member is against it, Already has HPV, Other.

Table 3 shows the influence of vaccine cost ($360–$500 versus free or much lower cost) and associations with the child’s insurance coverage among parents who were interested in vaccinating a currently unvaccinated daughter aged 9–17 (n = 683). A higher percentage of parents of children with private insurance (58.0%) than public (39.8%) or no insurance (39.5%) would vaccinate at that cost (p<0.01). Among respondents who would not pay $360–$500 for the vaccine or who cited expense as the main reason not to vaccinate their daughter (n = 272), 91.9% said that they would vaccinate if it was free or offered at a much lower cost with no significant difference by the child’s insurance coverage.

Table 3.

Influence of HPV vaccine cost on intention to vaccinate girls aged 9–17 years, by family insurance coverage and poverty threshold – National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2008

| n | Intend to vaccinate child if vaccine cost $360–$500a % (95% CI)b |

n | Intend to vaccinate child if vaccine free or at much lower costc % (95% CI)b |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Response | 683d | 51.6 (47.0–56.2) | 272d | 91.9 (86.9–95.1) |

|

| ||||

| Family insurance coverage | ||||

| No insurance | 73 | 39.5 (27.0–53.6) | 46 | 85.2 (66.4–94.3) |

| Public insurance | 175 | 39.8 (31.3–48.9) | 95 | 95.5 (89.4–98.2) |

| Private insurance | 431 | 58.0 (51.9–63.8) | 129 | 91.2 (82.7–95.8) |

| Family poverty threshold | ||||

| Below poverty | 81 | 44.3 (32.1–57.3) | 41 | 100.0 |

| At or above poverty, < 200% poverty | 139 | 39.8 (29.9–50.5) | 80 | 94.9 (88.6–97.8) |

| ≥ 200% poverty | 397 | 56.5 (50.4–62.4) | 127 | 89.4 (81.2–94.3) |

| Unknown | 66 | 55.2 (38.9–70.4) | 24 | 81.2 (49.5–95.0) |

Sample of unvaccinated female children aged 9–17 years whose respondent would be interested in getting the HPV vaccine for her.

Percentages are weighted to the population of girls aged 9–17 years.

Sample of unvaccinated female children aged 9–17 years whose respondent would not pay $360–$500 for the HPV vaccine or for whom the main reason to not get the vaccine was because it was too expensive.

Numbers may not add to 683 or to 282 because of missing data.

DISCUSSION

According to our analysis of nationally representative data, less than one quarter of pre-adolescent and adolescent girls had initiated the HPV vaccination series in 2008. However, the distribution of vaccine uptake in our study provides evidence that HPV vaccine uptake was occurring evenly among demographic groups at higher risk of cervical cancer. This is in contrast to findings in other studies in which concerns have been raised about the inequitable distribution of HPV vaccines.13, 19, 24 Although higher cervical cancer incidence and mortality is found among non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women compared with non-Hispanic white women, our adjusted results indicate no significant difference in vaccine initiation among these racial/ethnic groups.7 Asian adolescents had lower vaccine initiation than other groups. Like the overall group, the most common reasons that Asian parents did not vaccinate their daughters were the perception that their daughters did not need vaccine or were not sexually active, and lack of vaccine information (results not shown). Previous findings of lower HPV vaccine acceptability among Asian-American parents and low vaccine initiation among Asians suggest a priority for future programming and research.25 Similar to other studies, no significant difference in vaccine uptake by poverty status was found15, 20, and parents with lower levels of education were more likely to accept HPV vaccination for their daughters.10, 25, 26 These are encouraging findings because increased poverty and lower education level have been associated with greater incidence of cervical cancer.8 In addition, some national surveys that have found higher HPV vaccine uptake among those below the poverty line.19, 27

Similar to other studies, adolescents in our study who had a well-child check-up or flu shot in the past 12 months were more likely to have initiated the HPV vaccination series.15, 16, 18, 28 This finding supports continued efforts to promote an 11–12 year old health visit to administer the recommended vaccines and provide other routine preventive care services, as described in the adolescent vaccination platform, as well as reducing missed opportunities for vaccination by using all visits as an opportunity to vaccinate.29–31 The higher HPV vaccine initiation among those who received the flu vaccine suggests a potential for increased HPV vaccine uptake if it is given concomitantly with other ACIP-recommended vaccines.

We found that most parents not intending to vaccinate their daughters did not feel a sense of urgency for vaccinating girls while in the target age group, or lacked information to make a decision. Common reasons not to vaccinate cited in our study, such as “does not need vaccine,” “too young for vaccine,” and “not sexually active,” suggest that some parents were not aware of their daughters’ risk for HPV infection and the importance of vaccination during the target age range (11–12 years) before the initiation of sexual activity. This is similar to other studies which showed that parents and providers were more likely to vaccinate or intend to vaccinate older adolescents.17–20, 32–34 Delayed vaccination may result in girls missing the window to receive timely protection against cervical cancer before they become sexually active, and providers should stress to parents the importance of vaccinating their daughters while in the target age range.10, 15 A common reason given by parents for not vaccinating their daughters in our and other studies was insufficient information about the vaccine.10, 17 Lack of information may also reflect a lack of understanding among parents and adolescents about HPV infection, its potential disease outcomes, and cervical cancer prevention, as well as a lack of communication between parents, adolescents and their vaccination providers on these issues.35

Although cost was not a main reason offered by parents for not vaccinating their daughters, only half of those interested in future vaccination were willing to vaccinate at the current market price ($360 $500). More than 90% of parents who were not willing to pay this price, however, would immunize if the vaccine was free or cost much less. Financial barriers to HPV vaccination and lack of insurance or underinsurance of adolescents for vaccination have been reported by parents and providers in previous studies.26, 36–38 Similar to another study of national HPV vaccine uptake, our study found that girls without health insurance coverage were less likely to be vaccinated than those with public or private insurance.20 Our study also found that parents of children with no coverage or public insurance were less likely to intend to vaccinate their daughters at the current market price than those with private insurance.

These results suggest that many families may not be aware of, or are not accessing, public programs designed to provide HPV vaccines to underserved girls. Girls who lack insurance or who are underinsured and receive vaccines through a Federally Qualified Health Center or Rural Health Clinic may be eligible for the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program or state health department immunization programs. These programs provide funding for vaccination of children and adolescents <19 years of age who might not be vaccinated because of inability to pay.39 Our results indicate that more effective implementation of the VFC program and state supplemental funding could improve vaccine coverage for underserved girls. However, overall health access barriers and office visit fees, which are not covered by the VFC program, also need to be effectively addressed for increased vaccine coverage.39

In the United States, several national surveys provide surveillance data for HPV vaccine coverage.40 We are able to compare our findings for HPV vaccine uptake among adolescents aged 13–17 in NHIS 2008 with estimates from the 2008 National Immunization Survey (NIS)-Teen. The NIS-Teen reported that 37.2% received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine, and 17.9% received three doses, which are substantially higher percentages than our NHIS estimates.27 Although both are nationally representative surveys, different sampling methods, survey administration, and vaccination status reporting may explain the difference in the results.22, 41, 42 NHIS is an in-person household interview that represents households with or without landlines; NIS-Teen uses telephone random-digit dialing, and includes households that have only landlines. NHIS is possibly a more representative sample of the general population, but it is based on parent-reported data and is subject to recall bias. The NIS-Teen data uses parental response verified by medical records and its vaccination status is more accurate. More recent NIS-Teen results from 2009 showed an increase in HPV vaccine coverage of at least one dose to 44.3% and all three doses to 26.7%.19

We acknowledge that there are limitations to our findings. First, vaccination status may be subject to recall error because it is based solely on parent recall and not provider verified. Vaccination coverage using parent recall in the younger pediatric and adolescent populations may under- or overestimate true coverage.43–45 In NHIS, age and date at vaccination are unknown; hence, estimates of vaccine uptake by age cohort may be underestimates that reflect girls not having had the opportunity to be vaccinated before they took the survey, especially since some VFC programs might have experienced a delay in implementing this new vaccine. Lower series completion rates may also represent actual decreased compliance with subsequent doses, which may be problematic since vaccine efficacy with fewer than 3 doses is not known.4, 46 Finally, some variables that may be important predictors of vaccination, such as provider recommendation, were not explored in this survey.12, 15, 17 However, we are able to identify the proportion of parents who would have their child vaccinated even if their physician recommended it. Our finding that 47% of parents would not do so should be explored further in future studies. NHIS includes data on a variety of sociodemographic and preventive health behaviors through linkage with other NHIS child and adult modules. As the number of vaccinated girls rises, there will be the potential to examine further predictors of vaccination from this survey, including parental preventive behaviors, such as adult vaccination and cervical cancer screening.

CONCLUSION

HPV vaccines have the potential to significantly reduce the burden of cervical cancer. The limited HPV vaccine uptake found in this study emphasizes the need for focused public health messages and interventions to promote initiation and completion of all HPV vaccine doses recommended for preadolescent and adolescent girls. Further studies are needed to determine if interventions shown to be effective in pediatric age groups, such as client and provider reminders, increased vaccine access in health care settings, and reduced out-of-pocket costs, are appropriate for adolescents.31 Other proposed strategies for increasing adolescent vaccination are using the adolescent vaccine platform, giving multiple vaccines during one visit, reducing missed opportunities to immunize, and using alternative vaccine settings, such as schools.30, 47 Based on our findings, interventions to increase HPV vaccine uptake should reinforce vaccinating girls in the target age group and promote awareness of and access to free vaccines for uninsured and underinsured girls. Providers should be educated about HPV disease risk and vaccine benefits and should be encouraged to give parents information on the vaccines. In addition, interventions should promote adolescent well-child check-ups. CDC’s preteen vaccine campaign (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/preteen) is an example of such an intervention. With focused public health interventions, we anticipate that vaccine uptake among girls could increase.

Acknowledgments

Source of Support: This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Department of Health and Human Services or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

We would like to thank Shannon Stokely and Robin Curtis for their contributions. Charlene Wong and Jennifer Lee completed this project during their 1-year fellowship The CDC Experience, a public/private partnership supported by a grant to the CDC Foundation from External Medical Affairs, Pfizer Inc.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: No financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. Jama. 2007;297(8):813–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch FX, de Sanjose S. Chapter 1: Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer--burden and assessment of causality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;(31):3–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greer CE, Wheeler CM, Ladner MB, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) type distribution and serological response to HPV type 6 virus-like particles in patients with genital warts. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(8):2058–63. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2058-2063.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Recommended Immunization Schedules for Persons Aged 0 Through 18 Years ---United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;58(51&52):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brookfield KF, Cheung MC, Lucci J, Fleming LE, Koniaris LG. Disparities in survival among women with invasive cervical cancer: a problem of access to care. Cancer. 2009;115(1):166–78. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson M, Saraiya M, Benard V, et al. Burden of cervical cancer in the United States, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2855–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benard VB, Johnson CJ, Thompson TD, et al. Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2910–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conroy K, Rosenthal SL, Zimet GD, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake, predictors of vaccination, and self-reported barriers to vaccination. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(10):1679–86. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenthal SL, Rupp R, Zimet GD, et al. Uptake of HPV vaccine: demographics, sexual history and values, parenting style, and vaccine attitudes. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(3):239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Jin Y, Huang B, Namakydoust A, Zimet GD. Rates of human papillomavirus vaccination, attitudes about vaccination, and human papillomavirus prevalence in young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(5):1103–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817051fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerry SL, De Rosa CJ, Markowitz LE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in high-risk communities. Vaccine. 2011;29(12):2235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook RL, Zhang J, Mullins J, et al. Factors associated with initiation and completion of human papillomavirus vaccine series among young women enrolled in Medicaid. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(6):596–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, Reiter PL, et al. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescent girls in a high-risk geographic area. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(3):197–204. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f12dbf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caskey R, Lindau ST, Alexander GC. Knowledge and early adoption of the HPV vaccine among girls and young women: results of a national survey. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao C, Velicer C, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ. Correlates for human papillomavirus vaccination of adolescent girls and young women in a managed care organization. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(3):357–67. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT, Sternberg MR, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation in an area with elevated rates of cervical cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):430–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dempsey A, Cohn L, Dalton V, Ruffin M. Patient and clinic factors associated with adolescent human papillomavirus vaccine utilization within a university-based health system. Vaccine. 2010;28(4):989–95. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years --- United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(32):1018–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor LD, Hariri S, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2008. Prev Med. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anhang Price R, Tiro JA, Saraiya M, Meissner HI, Breen N. Use of human papillomavirus vaccines among young adult women in the United States: An analysis of the 2008 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics. [accessed 31 Dec 2009];National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release: NHIS Survey Description. 2008 Available from URL: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2008/srvydesc.pdf.

- 23.Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):652–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bach PB. Gardasil: from bench, to bedside, to blunder. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):963–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Constantine NA, Jerman P. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among Californian parents of daughters: a representative statewide analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(2):108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(2–3):107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years--United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(36):997–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiter PL, Cates JR, McRee AL, et al. Statewide HPV Vaccine Initiation Among Adolescent Females in North Carolina. Sex Transm Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d73bf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broder KR, Cohn AC, Schwartz B, et al. Adolescent immunizations and other clinical preventive services: a needle and a hook? Pediatrics. 2008;121 (Suppl 1):S25–34. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1115D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Middleman AB, Rosenthal SL, Rickert VI, Neinstein L, Fishbein DB, D'Angelo L. Adolescent immunizations: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(3):321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 Suppl):97–140. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahn JA, Ding L, Huang B, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, Frazier AL. Mothers' intention for their daughters and themselves to receive the human papillomavirus vaccine: a national study of nurses. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1439–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marlow LA, Waller J, Wardle J. Parental attitudes to pre-pubertal HPV vaccination. Vaccine. 2007;25(11):1945–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daley MF, Crane LA, Markowitz LE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices: a survey of US physicians 18 months after licensure. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):425–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klug SJ, Hukelmann M, Blettner M. Knowledge about infection with human papillomavirus: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2008;46(2):87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freed GL, Cowan AE, Clark SJ. Primary care physician perspectives on reimbursement for childhood immunizations. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1319–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman AL, Shepeard H. Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and communication preferences of the general public regarding HPV: findings from CDC focus group research and implications for practice. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(3):471–85. doi: 10.1177/1090198106292022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith PJ, Lindley MC, Shefer A, Rodewald LE. Underinsurance and adolescent immunization delivery in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124 (Suppl 5):S515–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Vaccines for Children Program. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/26 Apr 2010]

- 40.Tiro JA, Saraiya M, Jain N, et al. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer behavioral surveillance in the US. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):3013–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain N, Singleton JA, Montgomery M, Skalland B. Determining accurate vaccination coverage rates for adolescents: the National Immunization Survey-Teen 2006. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(5):642–51. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montgomery M, Khare M, Wouhib A, Singleton J, Jain N. Assessment of bias in the National Immunization Survey-Teen: benchmarking to the National Health Interview Survey. Abstract presented at the American Association for Public Opinion Research Conference; 2008 May 15–18; New Orleans. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luman ET, Ryman TK, Sablan M. Estimating vaccination coverage: validity of household-retained vaccination cards and parental recall. Vaccine. 2009;27(19):2534–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolton P, Holt E, Ross A, Hughart N, Guyer B. Estimating vaccination coverage using parental recall, vaccination cards, and medical records. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(6):521–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorell C, Yankey D, Jain N. Validity of parent-reported vaccination status for adolescents aged 13–17 years, National Immunization Survey-Teen, 2008. Pediatric Academic Socieities' Annual Meeting; Vancouver, Canada. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neubrand TP, Breitkopf CR, Rupp R, Breitkopf D, Rosenthal SL. Factors associated with completion of the human papillomavirus vaccine series. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009;48(9):966–9. doi: 10.1177/0009922809337534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Middleman AB. New adolescent vaccination recommendations and how to make them “stick”. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(4):411–6. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3281e72cd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]