Abstract

Over 20000 lipid extracts of plants and marine organisms were evaluated in a human breast tumor T47D cell-based reporter assay for hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) inhibitory activity. Bioassay-guided isolation and dereplication-based structure elucidation of an active extract from the Bael tree (Aegle marmelos) afforded two protolimonoids, skimmiarepin A (1) and skimmiarepin C (2). In T47D cells, 1 and 2 inhibited hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation with IC50 values of 0.063 µM and 0.068 µM, respectively. Compounds 1 and 2 also suppressed hypoxic induction of the HIF-1 target genes GLUT-1 and VEGF. Mechanistic studies revealed that 1 and 2 inhibited HIF-1 activation by blocking the hypoxia-induced accumulation of HIF-1α protein. At the range of concentrations that inhibited HIF-1 activation, 1 and 2 suppressed cellular respiration by selectively inhibiting the mitochondrial electron transport chain at complex I (NADH dehydrogenase). Further investigation indicated that mitochondrial respiration inhibitors such as 1 and rotenone induced the rapid hyperphosphorylation and inhibition of translation initiation factor eIF2α and elongation factor eEF2. The inhibition of protein translation may account for the short-term exposure effects exerted by mitochondrial inhibitors on cellular signaling, while the suppression of cellular ATP production may contribute to the inhibitory effects following extended treatment periods.

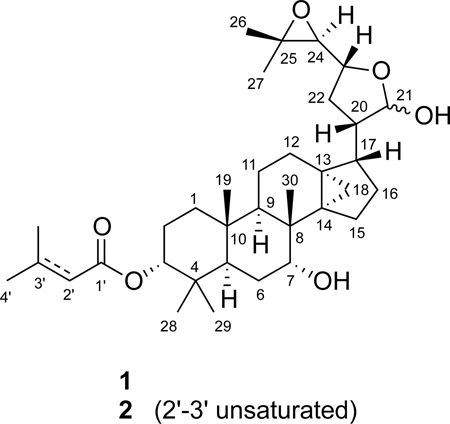

Aegle marmelos (L.) Corrêa ex Roxb. (Rutaceae), commonly known as Bael tree, is widely distributed throughout India, Burma, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and other parts of Southeast Asia.1 In Indian Ayurvedic medicine, Bael tree parts are used to treat disorders that range from cardiac malfunction to diarrhea.1 Crude extracts of this plant have exhibited pharmacological efficacy in various animal models.1 Chemical investigations of A. marmelos have yielded coumarins,2,3 protolimonoids,4,5 anthraquinones,6,7 amide alkaloids,8–10 and lignan glucosides.11 In a continuing search for small-molecule HIF-1 inhibitors as potential anticancer agents from natural sources, the lipid extract of A. marmelos trunk bark was found to inhibit hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation (93% inhibition at 5 µg mL−1) in a human breast tumor T47D cell-based reporter assay.12 A key regulator of oxygen homeostasis, the transcription factor HIF-1 promotes cellular adaptation and survival under hypoxic conditions by regulating gene expression.13 Extensive preclinical and clinical studies support the inhibition of HIF-1 as an important molecular-targeted approach for anticancer drug discovery.13 Bioassay-guided chromatographic separation of the active A. marmelos extract led to the isolation of two previously identified protolimonoids, skimmiarepin A (1)4 and skimmiarepin C (2).5 This report describes the identification and characterization of 1 and 2 as potent HIF-1 inhibitors. Further mechanistic studies revealed that these protolimonoids suppress mitochondrial respiration at electron transport chain (ETC) complex I and inhibit eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-α (eIF2α) and eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

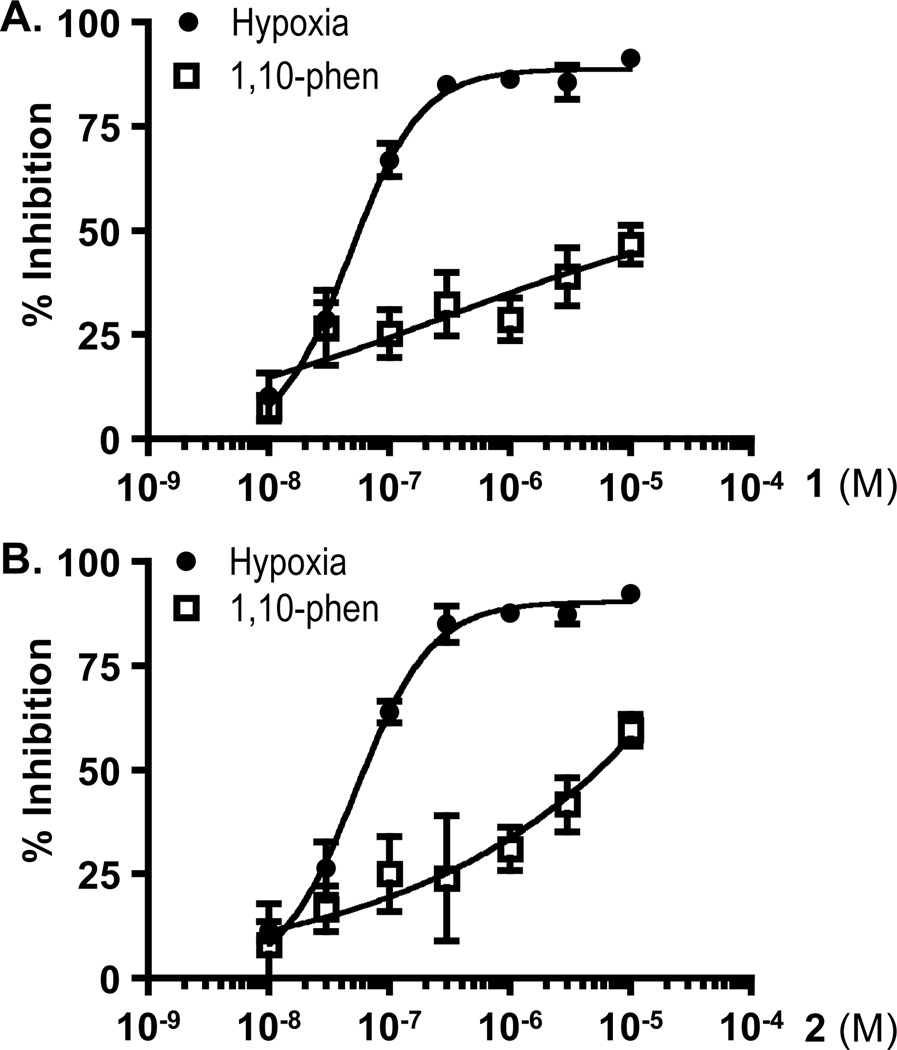

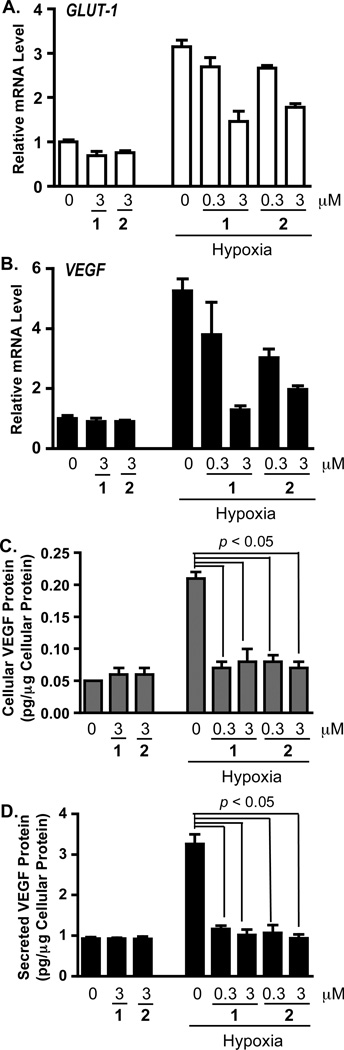

The non-polar extract of A. marmelos from the U.S. National Cancer Institute “NCI Open Repository” inhibited hypoxia (1% O2)-induced HIF-1 activation by 93% at 5 µg mL−1 in a T47D cell-based reporter assay. Bioassay-guided isolation and subsequent dereplication-based structure elucidation afforded two known protolimonoids, 1 and 2.4,5 In the T47D cell-based reporter assay,12 both compounds suppressed hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation with comparable nanomolar IC50 values (63 nM for 1, and 68 nM for 2; Figures 1A and 1B). The HIF-1 inhibitory effects exerted by 1 and 2 appear to be inducing condition-dependent. They were at least 80 times less potent at inhibiting HIF-1 activation by the iron chelator 1,10-phenanthroline (IC50 values >10 µM for 1, and 5.6 µM for 2; Figures 1A and 1B), relative to their effects on hypoxia-induced HIF activation. Among the HIF-1 target genes, GLUT-1 and VEGF are induced by hypoxia in a HIF-1 dependent manner in a majority of the cell types and cell lines examined.13 In T47D cells, 1 and 2 suppressed the hypoxic induction of GLUT-1 and VEGF mRNAs (Figure 2A and 2B). VEGF promotes tumor angiogenesis by stimulating new blood vessel formation and agents that inhibit VEGF are in clinical use for cancer treatment.14 Compounds 1 and 2 blocked the hypoxic induction of both cellular and secreted VEGF proteins (Figure 2C and 2D). At the lower concentration (0.3 µM), 1 and 2 exerted more pronounced inhibitory effects on the induction of VEGF at the protein level (Figures 2C and 2D), relative to the effects on mRNA levels (Figure 2B). Under normoxic conditions, neither compound suppressed the expression of HIF-1 target genes (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Skimmiarepins inhibit HIF-1 activation.

(A) Skimmiarepin A (1) inhibits HIF-1 activation in a concentration-dependent manner. T47D cells transfected with the pTK-HRE3-luc reporter construct were exposed to HIF-1 activating conditions [hypoxia (1% O2, 16 h, ●), and chemical hypoxia (10 µM 1,10-phenanthroline, 16 h, ▯)] in the presence and absence of compound 1 at the specified concentrations. Luciferase activities were determined and presented as "% Inhibition" of the induced control. Data shown are averages ± standard deviations from one representative experiment performed in triplicate. (B) Skimmiarepin C (2) exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition of HIF-1 activation similar to those observed in the presence of 1. Experimental conditions and data presentation are the same as those described in (A).

Figure 2. Skimmiarepins inhibit hypoxic induction of HIF-1 target genes.

(A) Compounds 1 and 2 inhibit the induction of Glut-1 mRNA by hypoxia. T47D cells were exposed to 1 and 2 at the specified concentrations under normoxic (95% air, 16 h) and hypoxic conditions (1% O2, 16 h). Total RNA samples were isolated from each specified condition, and the levels of Glut-1 mRNA determined by quantitative real time RT-PCR and normalized to an internal control (18S rRNA) using the ΔΔCT method. Data are presented as relative mRNA level of the normoxic control. (B) Compounds 1 and 2 inhibited hypoxic induction of VEGF mRNA in T47D cells. Experimental conditions, data acquisition, processing, and presentation were the same as those described in (A). (C) Compounds 1 and 2 suppress hypoxic induction of cellular VEGF protein in T47D cells. Compound treatment was the same as that described in (A) and (B). Levels of VEGF protein in the cell lysate samples were determined by ELISA and normalized to the amount of cellular proteins. Data shown are averages + standard deviations (n = 3) from one experiment. (D) Compounds 1 and 2 block hypoxic induction of secreted VEGF protein. Experimental conditions were the same as those described in (C). Levels of secreted VEGF proteins were determined by ELISA analysis of the T47D cell-conditioned media samples.

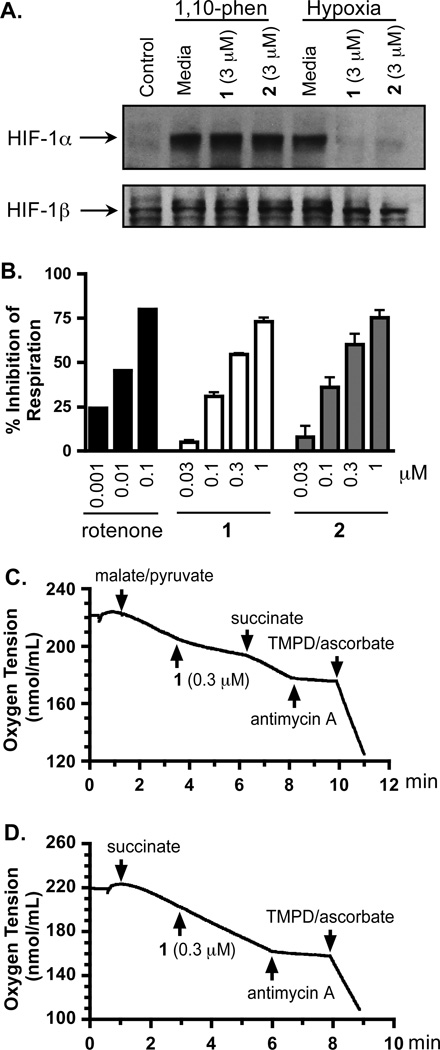

In general, the availability and activity of the oxygen-regulated HIF-1α protein determines HIF-1 activity.13 In the presence of oxygen, HIF-1α protein is rapidly degraded. Exposure to hypoxia, iron chelators, and transition metals can each stabilize and activate HIF-1α protein. To investigate the mechanism(s) of action for the skimmiarepins to inhibit HIF-1 activation, we first examined the effects of 1 and 2 on the levels of nuclear HIF-1α protein in T47D cells. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α protein was not detected by western blot (Control, Figure 3A). Hypoxic exposure induced the accumulation of HIF-1α protein (Media, Hypoxia; Figure 3A). Compounds 1 and 2 suppressed the hypoxic induction of HIF-1α protein (1 and 2, Hypoxia; Figure 3A). By contrast, neither compound affected the induction of HIF-1α protein by 1,10-phenanthroline, an iron chelator (1, and 2, 1,10-phen; Figure 3A). Levels of the constitutively expressed HIF-1β protein were not affected by compounds 1 and 2 (Figure 3A). These observations suggest that 1 and 2 inhibited HIF-1 activation by blocking the hypoxic induction of HIF-1α protein. Among the natural products examined, compounds that disrupt mitochondrial function constitute a group of HIF-1 inhibitors that selectively suppress the activation of HIF-1 by hypoxia.15 To test the hypothesis that skimmiarepins may function as mitochondrial inhibitors, a T47D cell-based oxygen consumption study was performed to determine the effects of 1 and 2 on cellular respiration. Compounds 1 and 2 suppressed respiration at the same range of concentrations that inhibited HIF-1 activation by hypoxia (respiration: Figure 3B; HIF-1 inhibition: Figures 1B and 1C). At the highest concentration tested (1 µM), 1 and 2 inhibited T47D cell respiration by 73% and 75%, respectively (Figure 3B). Since 1 and 2 exhibited similar bioactivities and they only differ by the presence or absence of a double bond in the ester residue at C-3, compound 1 was selected as a representative for mechanistic studies to discern the site(s) within the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) targeted by skimmiarepins. The addition of a mixture of malate and pyruvate to permeabilized T47D cells initiated mitochondrial respiration at complex I that was suppressed by 1 (Figure 3C). The complex II substrate succinate overcame this inhibition. Meanwhile, 1 did not inhibit mitochondrial respiration initiated at complex II by succinate (Figure 3D). To ensure that ETC complexes III and IV remained functional, antimycin A was added to inhibit respiration at complex III and a mixture of TMPD/ascorbate was added to re-initiate respiration at complex IV (Figures 3C and 3D). These results mirrored those observed in the presence of the commonly used complex I inhibitor rotenone.16 Thus, these data indicate that 1 inhibits mitochondrial ETC complex I and does not significantly inhibit complex II, III, or IV.

Figure 3. Skimmiarepins inhibit hypoxic induction of HIF-1α protein and mitochondrial electron transport chain at complex I.

(A) Compounds 1 and 2 block the induction of HIF-1α protein by hypoxia (1% O2, 4 h), but not that by 1,10-phenanthroline (10 µM, 4 h). Nuclear extract samples from T47D cells exposed to each specified condition were subjected to western blot analysis for the levels of HIF-1α and HIF-1β proteins. (B) Compounds 1 and 2 suppress cellular respiration in a concentration-dependent manner. T47D cell respiration rates were measured in the presence and absence of compounds at the specified concentrations. Data are presented as "% Inhibition" of the untreated control (average + standard deviation from three independent experiments for 1 and 2, and one representative experiment for rotenone). (C) Compound 1 suppressed mitochondrial respiration at complex I. A mixture of malate and pyruvate was added to digitonin-permeabilized T47D cells to initiate respiration at complex I. The inhibition exerted by 1 on complex I was overcome by succinate, a substrate for complex II. The complex III inhibitor antimycin A and complex IV substrates TMPD/ascorbate were added in a sequential manner to ensure that the ETC remained functional. (D) Compound 1 did not affect mitochondrial respiration in the presence of succinate.

Little is known about the biological activities of the skimmiarepins. One study reported that they have potent insecticidal activity.5 A concentration-response study was performed to determine the effects of 1 and 2 on tumor cell proliferation/viability. Among the three cell lines examined, human breast tumor T47D cells were most sensitive to the cytostatic/cytotoxic effects of 1 and 2 and human breast tumor MDA-MB-231 cells were least sensitive (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Human prostate tumor PC-3 cells exhibited a moderate level of sensitivity. Extended exposure time (6 day versus 2 day) significantly enhanced the inhibitory effects exerted by 1 and 2 in all three cell lines. These results correlate with previous observations that mitochondrial respiration inhibitors require prolonged incubation time to suppress tumor cell proliferation/viability.17

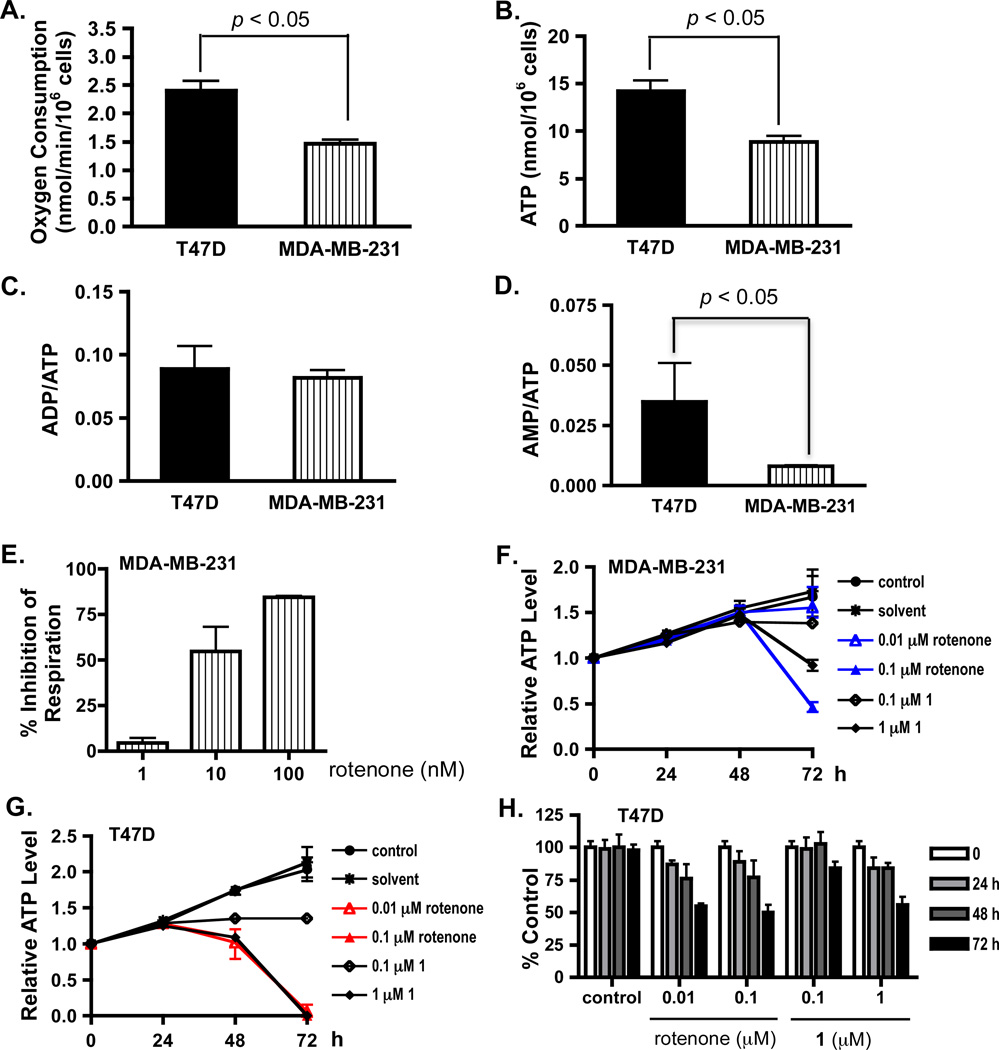

To investigate the mechanism(s) that contribute to the cell line-dependent antiproliferative effect of skimmiarepins, T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were selected as in vitro models for distinct breast cancer subtypes. T47D cells are estrogen receptor (ER)- and progesterone receptor (PR)-positive, and represent the less aggressive luminal subtype, while MDA-MB-231 cells are ER- and PR-negative, highly invasive, and represent the more aggressive basal subtype.18 As indicators of cellular bioenergetics, the rate of cellular respiration, and levels of ATP, ADP, and AMP were determined in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells consume oxygen at 58% of the rate observed in T47D cells (Figure 4A), and yield 37% less ATP than T47D cells (Figure 4B). The ratio of ADP/ATP (Figure 4C) was comparable between T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, while the ratio of AMP/ATP was higher in T47D cells (Figure 4D). These observations suggest that MDA-MB-231 cells respire at a slower rate, and generate proportionally less ATP, presumably due to their reduced rate of oxidative phosphorylation. To determine if the electron transport chain functions similarly between T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, a concentration-response study was performed to quantify the effects of the commonly used complex I inhibitor rotenone on cellular respiration. At lower concentrations, rotenone suppressed cellular respiration to a lesser extent in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 4E) than that observed in T47D cells (Figure 3B) (serum-free DMEM/F12 medium, 30 °C).

Figure 4. Skimmiarepin A decreases T47D cell ATP production and proliferation/viability in a concentration- and treatment time-dependent manner.

(A) Respiration rate in exponentially grown T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. Oxygen consumption was monitored at 37 °C, and the rate of oxygen consumption was presented as average + standard deviation from three independent experiments. Data were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni analysis. (B) Cellular ATP levels in exponentially grown T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. The cells were lysed, the ATP levels were determined by a HPLC-based method, and normalized to the number of cells plated. Data were compared and presented as previously described in (A). (C) ADP/ATP ratios in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (average + standard deviation, n = 3). There is no statistically significant difference between these two cell lines. (D) AMP/ATP ratios in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. Data were compared and presented as previously described in (C). (E) Rotenone exerts concentration-dependent inhibition of respiration in MDA-MB-231 cells. The oxygen consumption rate was monitored under 37 °C. Data shown are average + standard deviation from three independent experiments. (F) The mitochondrial inhibitors rotenone and compound 1 inhibited ATP production in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were exposed to test compounds or solvent control at the specified concentrations for 24, 48, and 72 h. The ATP levels in cell lysate samples were determined by HPLC and presented as "Relative ATP Level" of the media control before compound treatment (T0). Data shown are average + deviation from average of two independent experiments. (G) Rotenone and 1 decreased ATP levels in T47D cells. The experimental design and data presentation are as described in (F). (H) Mitochondrial inhibitors suppressed T47D cell proliferation/viability in a time-dependent manner. T47D cells were exposed to compounds at the specified concentrations for 24, 48, and 72 hours. Cell viability at each time point was determined by the SRB method and presented as "% Control" of the untreated control. Data shown are average + standard deviation from one experiment performed in triplicate.

To determine if the cytostatic/cytotoxic effects exerted by 1 correlate with the suppression of ATP production, a time-course study was performed to monitor the levels of ATP in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium, in the presence and absence of test compounds. No significant change in ATP levels was observed between the control and treated MDA-MB-231 cells at exposure times up to 48 h (Figure 4F). At the 72 h time point, both rotenone and 1 decreased cellular ATP levels in a concentration-dependent manner. A more pronounced inhibitory effect was observed in T47D cells (Figure 4G). Rotenone and 1 reduced cellular ATP levels after 48 h exposure and prolonged exposure enhanced the suppression. At 72 h, the detachment and/or loss of adhesive cells in rotenone (0.01 and 0.1 µM) and 1 (1 µM)-treated T47D cells most likely magnified the decrease in ATP levels. This notion is supported by the observation that rotenone (0.01 and 0.1 µM) and 1 (1 µM) only suppressed T47D cell proliferation/viability by ~50% in a parallel sulforhodamine B (SRB) method-based cell viability study (Figure 4H). The SRB method fixes cells directly in the wells without abrasive procedures (i.e., aspiration, wash, etc.) and is thus less likely to disturb the cells that are loosely attached.

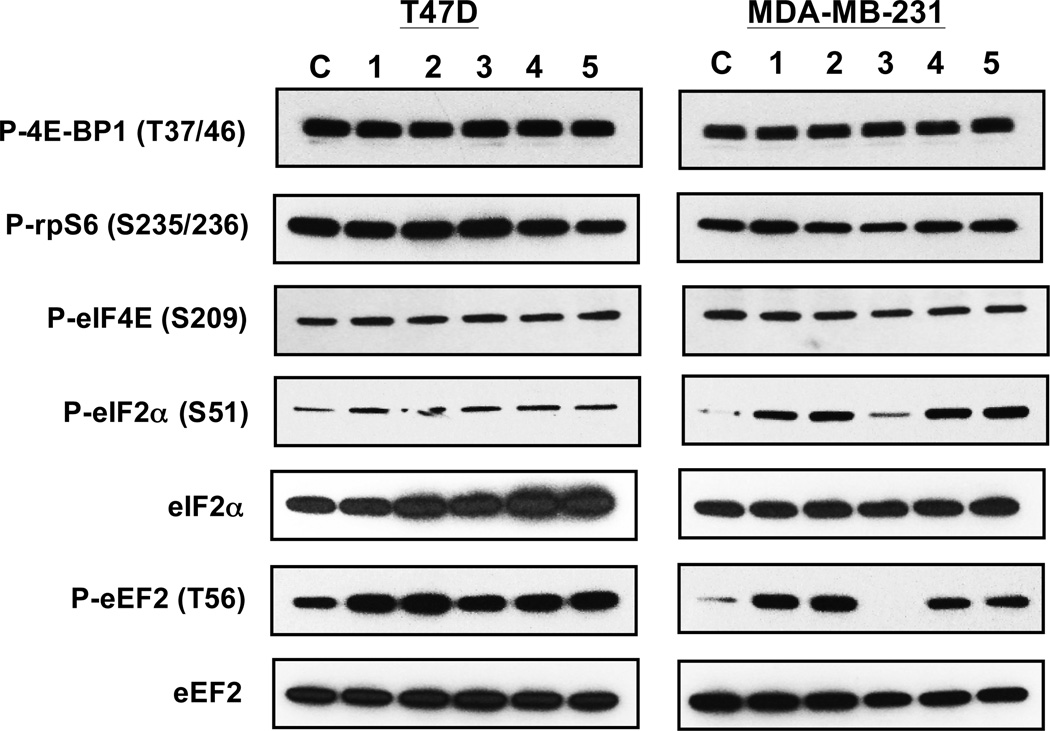

Although not universally accepted, one proposed mechanism for mitochondrial inhibitors to suppress hypoxia-activated HIF-1 is by blocking the production of hypoxia-induced mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) that stablize the HIF-1α protein.19,20 To investigate if other mechanism(s) also contribute to mitochondrial inhibitor-mediated HIF-1 inhibition, we examined the effects of 1 on representative signaling pathways that regulate protein translation. The commonly used complex I inhibitor rotenone was included to discern the consequence of disrupting mitochondrial function on these pathways. A mixture of 2-deoxyglucose and oligomycin (2-DG/oligomycin) was applied as a positive control for metabolic stress. The large Ser/Thr protein kinase mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) regulates cellular growth and metabolism in response to intra- and extracellular signals.21 The phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6) was examined to monitor mTORC1 activity. The phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 promotes cap-dependent translation by releasing eIF4E, while rpS6 phosphorylation increases ribosome biogenesis by enhancing the translation of ribosomal proteins.21 In serum-replete T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, rotenone, 1, and 2-DG/oligomycin did not exert significant effects on the activity of mTORC1 (P-4E-BP1 and P-rpS6; Figure 5). A component of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4F (eIF4F) complex, eIF4E is regulated at multiple levels including the phosphorylation of serine 209 that improves translation efficiency.22 Under experimental conditions, exposure to rotenone, 1, and 2-DG/oligomycin did not affect the phosphorylation of eIF4E in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (P-eIF4E; Figure 5). The assembly of eIF4E/eIF4A/eIF4G into eIF4F that binds the m7-GTP cap on mRNAs and that of the eIF2/GTP/Met-tRNA complex that binds the 40S ribosome constitute two important signaling nodes that regulate translation initiation.22,23 Phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-α (eIF2α) at Ser51 inhibits translation by preventing the formation of the eIF2/GTP/Met-tRNA complex.23 Mitochondrial inhibitors rotenone, 1, and 2-DG/oligomycin, induced the hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α at Ser51 [P-eIF2α (S51); Figure 5]. A more pronounced effect was observed in MDA-MB-231 cells, relative to the effect observed in T47D cells. At the concentrations tested, 1 exhibited concentration-dependent induction of eIF2α phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of the eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) was examined to determine if mitochondrial inhibitors also regulate translation elongation. The translation elongation factor eEF2 mediates the translocation step of protein synthesis and the phosphorylation of eEF2 at Thr56 inhibits translation by blocking the interaction between eEF2 and ribosome.24 Rotenone, 1, and 2-DG/oligomycin, each induced the hyperphosphorylation of eEF2 [P-eEF2 (T56); Figure 5]. Similar to that observed on the phosphorylation of eIF2α, 1 exhibited a more pronounced concentration-dependent effect on the hyperphosphorylation of eEF2 in MDA-MB-231 cells. These results suggest that the hyperphosphorylation and inhibition of eIF2α and eEF2 by 1 (Figure 5) correlates with the inhibition of respiration (Figure 3B). Thus, mitochondrial inhibitors may suppress translation by inhibiting the activities of eIF2 and eEF2. Further studies are required to identify the proteins that are tightly regulated by mitochondrial respiration inhibitors at the translation level.

Figure 5. Skimmiarepin A (1) and rotenone inhibit translation initiation and elongation factors.

T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to compound or control as specified for 30 min. The cell lysate samples were subjected to western blot analysis with antibodies against phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (P-4E-BP1), phosphorylated rpS6 (P-rpS6), phosphorylated eIF4E (P-eIF4E), phosphorylated eIF2α (P-eIF2α), phosphorylated eEF2 (P-eEF2), total eIF2α (eIF2α), and total eEF2 (eEF2) proteins, repectively. The treatment conditions are: control (C), 0.1 µM rotenone (1), 1 µM rotenone (2), 1 µM compound 1 (3), 10 µM compound 1 (4), and a mixture of 100 ng/mL oligomycin and 10 mM 2-deoxyglucose (5).

Although Bael tree has been widely used in traditional Indian medicine and its crude extracts have been extensively investigated for their pharmacological properties,1 the only reported biological activity of skimmiarepins A and C is insecticidal action against the mustard beetle Phaedon cochleariae and the house fly Musca domestica.5 These skimmiarepins are the first protolimonoids found to inhibit mitochondrial ETC complex I (NADH dehydrogenase). The ecological significance and potential agrochemical impact of our findings is that it appears likely that the rotenone-like activity of these protoliminoids may deter grazing by herbivores and be responsible for the reported insecticidal activities of these A. marmelos metabolites. Meanwhile, the mitochondrial disrupting effects of the skimmiarepins should be further investigated and closely monitored when Bael tree extracts are used as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) products.

In humans, mitochondrial respiration accounts for over 90% of cellular oxygen consumption.25 It is not surprising that mitochondria regulate the stability and activity of HIF-1, a key regulator of oxygen homeostasis. Despite intensive investigations conducted by numerous research groups, the nature of the mitochondria-mediated signaling events that regulate HIF-1 remains an area of considerable controversy.25 The “ROS hypothesis” proposes that hypoxia increases mitochondrial ROS production at ETC complex III, which then inactivates the hydroxylases that modify HIF-1α protein and leads to the stabilization and activation of HIF-1α protein.20,25 Small-molecule mitochondrial inhibitors suppress hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation by blunting hypoxia-induced mitochondrial ROS production.19 However, a number of studies including a recent report26 support the notion that hypoxia-induced stabilization of HIF-1α protein occurs independently of mitochondrial ROS. This “oxygen redistribution hypothesis” proposes that the mitochondrial ETC regulates hypoxic activation of HIF-1 by affecting the availability of oxygen to the hydroxylases that inactivate HIF-1.25,26 Under hypoxic conditions, mitochondria consume a large fraction of the available oxygen and inactivate hydroxylases by depleting intracellular oxygen. Mitochondrial inhibitors prevent hypoxic HIF-1 activation by increasing the level of cytosolic oxygen that eventually leads to the inactivation of HIF-1. Our results suggest that the regulation of translation may also contribute to the mitochondria-mediated signaling events that control HIF-1 activation. The observation that mitochondrial respiration inhibitors induce the hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α and eEF2 proteins suggests that the disruption of mitochondrial respiration may trigger a brake that stalls translation. The upstream kinase that may mediate mitochondrial inhibitor-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α is the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-α kinase 3 (EIF2AK3, or PERK). Acting as an ER stress sensor, PERK phosphorylates eIF2α upon activation and suppresses global protein translation.27 Our working hypothesis is that the mitochondrial inhibitor imposed metabolic stress can be signaled to the ER and prompts an ER stress response that arrests global protein translation. For the phosphorylation of eEF2, one possible candidate pathway is the transmission of signals via the AMP/ATP↑ - AMPK - eEF2K - eEF2 chain.23,28 However, no statistically significant change in the AMP/ATP ratio was detected after 15 and 30 min exposure of T47D cells to mitochondrial inhibitors such as rotenone (Supporting Information). Mitochondrial disruption with 2-deoxyglucose/oligomycin did not activate AMPK until after 4 hr of treatment (Supporting Information). Therefore, it appears that mitochondrial respiration inhibitors induce an AMPK-independent signaling event that results in the hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of eEF2. Further studies directed at discerning the crosstalk between mitochondria and translation are required to resolve this question.

In summary, we have discovered that protolimonoids skimmiarepin A (1) and C (2) inhibit mitochondrial respiration at the ETC complex I. In addition, 1 and the commonly used ETC complex I inhibitor rotenone induce a rapid stress response that stalls protein translation. The translation inhibitory effects exerted by respiration disruptors appear to be AMPK-independent. The disruption of mitochondrial function and the subsequent translational inhibition may account for the biological activities attributed to these protolimonoids. Since these compounds are found in CAM products that contain Bael tree extract, it is important that the mitochondrial disrupting properties of these compounds be considered as a safety concern of CAM products that contain such mitochondrial inhibitors.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures for Natural Product Chemistry

HPLC was conducted using a Waters system, equipped with a 600 controller and a 2424 evaporative light scattering detector (split ratio 20:1). Semi-preparative HPLC column (Phenomenex Luna RP-18, 5 µm, 250 × 10 mm) was employed for isolation. TLC were performed using Merck Si60F254 plates, sprayed with a 10% H2SO4 solution in EtOH, and heated to char. Optical rotations were obtained on an AP IV/589-546 digital polarimeter. NMR spectra were recorded on a AMX-NMR spectrometer (Bruker) operating at 400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C, respectively. Residual solvent peaks (δ 7.27 for 1H and δ 77.23 for 13C) were used as internal references for the NMR spectra recorded running gradients. The ESIMS were determined on a Bruker Daltonics micro TOF fitted with an Agilent 1100 series HPLC and an electrospray ionization source. The purities of 1 and 2 were judged on the percentage of the integrated signal at from the evaporative light scattering detector. Both compounds submitted for bioassay were at least 95% pure as judged by this method.

Plant Material

Aegle marmelos bark was collected from Sumba, eastern Indonesia (February, 1994). The plant material was identified by A. McDonald and a voucher specimen was deposited at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C.

Extraction and Isolation

Dried plant material was extracted with CH2Cl2-MeOH (1:1),29 residual solvents removed under vacuum, and the extract (NCI Open Repository collection number N085633) stored at −20 °C in the NCI Open Repository at the Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center (Frederick, Maryland). The crude extract (4.19 g sample from an NCI stock supply) was subjected to passage over a Sephadex LH-20 column eluted with CH2Cl2-MeOH (1:1) to afford six fractions. The fractions were evaluated for HIF-1 inhibitory activities in a T47D cell-based reporter assay.12 Active fraction B (1.23 g) was further separated into ten subfractions by C18 VLC column chromatography eluted with step gradients of 10% to 100% MeOH in H2O. The seventh subfraction (55 mg, eluted with 70% MeOH in H2O) was separated by semi-preparative HPLC [Luna 5 µm, C18(2), 100 Å, 250 × 10 mm, isocratic 80% MeOH in H2O, 4.0 mL min−1, ELSD detection] to produce 1 (2.5 mg, 0.05% yield, tR 23 min) and 2 (3.1 mg, 0.07% yield, tR 21 min). Dereplication-based structural elucidation by NMR identified 1 as skimmiarepin A (CAS Registry No. 118156-16-4) and 2 as skimmiarepin C (CAS Registry No. 690664-15-4). The spectroscopic and physical characteristics of 1 and 2 matched those reported for skimmiarepin A4 and skimmiarepin C,5 respectively.

Cell-Based Reporter and Proliferation/Viability Assays

Human breast tumor T47D, MDA-MB-231, and prostate tumor PC-3 cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM/F12 media with l-glutamine (Mediatech), supplemented with fetal bovine serum [FBS, 10% (v/v), Hyclone], potassium penicillin (50 units mL−1), and streptomycin sulfate (50 µg mL−1) (Lonza). The T47D cell-based pHRE3-TK-Luc reporter assay was performed as described to monitor HIF-1 activity.12 The 96-well plate-based cell viability assay procedure was similar to that described,30 except that fresh medium containing 5% FBS and test compound were used to replace the conditioned medium after 3 days in the 6-day viability study. Data were presented as % Inhibition of the induced control in the reporter assay, and % Inhibition of the medium control in the cell viability assay. The formula used was: % Inhibition = [1 − (ODtreated/ODcontrol)] × 100.

Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR and ELISA Assays

Preparation of RNA samples from compound treated and control T47D cells, synthesis of the first strand cDNAs, quantitative real-time PCR reactions with gene-specific primers, and data analysis were same as previously described.31 The acquisition of T47D cell-conditioned medium and cellular lysate samples in the presence and absence of test compounds, and ELISA assay for secreted and cellular VEGF proteins, were performed as those previously described.12 The amount of VEGF protein (secreted and cellular) was normalized to that of cellular proteins quantified using a micro BCA assay kit (Pierce).

Western Blot Analysis

The procedures to determine the levels of HIF-1α and HIF-1β proteins in the nuclear extract samples prepared from compound treated and control T47D cells were the same as described.16

For signaling pathway-related western blot analysis, exponentially grown T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at the density of 0.8 × 106 cells per well into 6-well plates. The cells were exposed to test compounds at the specified concentrations in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 5% FBS and a mixture of penicillin and streptomycin for 30 minutes at 37 °C under 5% CO2-95% air. The cells were washed once with cold Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) free of calcium, magnesium, and phenol red (Hyclone). A modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) supplemented with a mixture of protease inhibitors (Sigma, P2714) and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma, P5726 and P2850) were added in a volume of 150 µL per well to lyse the cells. After incubating on ice for 5 min, the cell lysates were scraped off, transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, and spun at 12000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to fresh tubes and stored at −80 °C. The concentration of proteins in the supernatant was determined using a micro BCA assay kit (Pierce). Standard SDS-PAGE and western blot methods were applied for the signaling pathway analysis. Cellular proteins (40 µg) were separated on 4–20% Tris-Glycine gels (Bio-Rad), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Primary antibodies against P-4E-BP1 (T37/46), P-S6 (S235/236), P-eIF4E (S209), P-eIF2α (S51), P-eEF2 (T56), eIF2α, and eEF2 were purchased from Cell Signaling and used at 1:1,000 dilution following manufacturer's instructions. A horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, 1:2000 dilution) was used to detect the primary antibodies. The membrane was developed with a Supersignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Reagent System (Pierce) and exposed to X-ray films.

Cell Respiration Assay

An Oxytherm Clarke-type electrode system (Hansatech) was used to monitor cellular oxygen consumption. For T47D cell-based respiration studies to determine the effects of test compounds on cellular respiration and to investigate the mechanism of action, the experiments were performed as described.16 To compare the rates of cellular respiration between T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, the respiration studies were conducted similar to those previously described16 except that the cells and solutions were equilibrated to 37 °C.

HPLC-UV-Based Determination of Cellular ATP, ADP, and AMP Levels

Exponentially grown T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at the density of 5 × 105 cells per well into 12-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) in DMEM/F12 medium with l-glutamine, 10% FBS, and a mixture of Pennicillin/Streptomycin, as previously described. Following 24 h incubation, half of the conditioned medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM/F12 medium containg Penn/Strep and test compounds. After the cells were exposed to compounds for the specified amount of time, the conditioned medium was removed by aspiration, the cells were washed once with cold DPBS free of calcium, magnesium, and phenol red (Hyclone), and lysed with cold 0.4 M perchloric acid (100 µL per well, −80 °C 1 h). The cell lysates were thawed on ice, transferred to 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes, the wells were washed once with dd-H2O (100 µL per well), the wash solution pooled with the lysates, and the tubes centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and neutralized with the addition of 10 µL 4 M K2CO3. The mixture was subjected to centrifugation at 14000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant samples were transferred to new tubes and stored at −20 °C pending further analysis. The HPLC-based analyses were performed using an HPLC system that consisted of a Waters 600 pump and controller and a UV/vis photodiode array 2998 detector. Chromatographic separations were carried out on a Nova-Pak C18 ODS column (150 mm × 3.9 mm i.d., 5 µm particle size, Waters) with a C18 Guard column (4.0 mm × 3.0 mm i.d., 5 µm particle size, Phenomenex), at a flow rate of 0.7 mL min−1 with an injection volume of 20 µL. The mobile phases were composed of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0 (A) and MeOH (B). Isocratic elution was performed with a mixture of 99A:1B. The DAD detected analytes at 257 nm. Standards for ATP, ADP, and AMP were purchased from Sigma.

Statistical Analysis

Data comparison was performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analyses using GraphPad Prism 4. Differences between data sets were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the Natural Products Branch Repository Program at the National Cancer Institute for providing marine extracts from the NCI Open Repository used in these studies, D. J. Newman and E. C. Brown (NCI, Frederick, MD) for assistance with sample logistics and collection information, S. L. McKnight (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas) for providing the pTK-HRE3-luc construct, Y. Yang (NHGRI, NIH) and D. Reines (Emory University) for their input on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (grant CA98787), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Institute for Undersea Science and Technology (grant NA16RU1496). This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with Research Facilities Improvement Grant C06 RR-14503-01 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Skimmiarepins inhibit tumor cell proliferation/viability in a concentration-, cell Line-, and time-dependent manner. Effects of mitochondrial inhibitors on the ratio of AMP/ATP in T47D cells. Exposure time-dependent activation of AMPK in T47D cells. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maity P, Hansda D, Bandyopadhyay U, Mishra DK. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2009;47:849–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohashi K, Watanabe H, Ohi K, Arimoto H, Okumura Y. Chem. Lett. 1995;24:881–882. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali MS, Pervez MK. Nat. Prod. Res. 2004;18:141–146. doi: 10.1080/14786410310001608037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ochi M, Tatsukawa A, Seki N, Kotsuki H, Shibata K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1988;61:3225–3229. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samarasekera JKRR, Khambay BPS, Hemalal KP. Nat. Prod. Res. 2004;18:117–122. doi: 10.1080/1478641031000149858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra BB, Kishore N, Tiwari VK, Singh DD, Tripathi V. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra BB, Singh DD, Kishore N, Tiwari VK, Tripathi V. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma BR, Rattan RK, Sharma P. Phytochemistry. 1981;20:2606–2607. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narender T, Shweta S, Tiwari P, Reddy KP, Khaliq T, Prathipati P, Puri A, Srivastava AK, Chander R, Agarwal SC, Raj K. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:1808–1811. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phuwapraisirisan P, Puksasook T, Jong-aramruang J, Kokpol U. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:4956–4958. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohashi K, Watanabe H. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994;42:1924–1926. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodges TW, Hossain CF, Kim YP, Zhou Y-D, Nagle DG. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:767–771. doi: 10.1021/np030514m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semenza GL. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2010;2:336–361. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrara N, Mass RD, Campa C, Kim R. Annu. Rev. Med. 2007;58:491–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.061705.145635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagle DG, Zhou Y-D. Phytochem. Rev. 2010;8:415–429. doi: 10.1007/s11101-009-9120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Veena CK, Morgan JB, Mohammed KA, Jekabsons MB, Nagle DG, Zhou Y-D. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:5859–5968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806744200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaughlin JL. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:1311–1321. doi: 10.1021/np800191t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neve RM, Chin K, Fridlyand J, Yeh J, Baehner FL, Fevr T, Clark L, Bayani N, Coppe JP, Tong F, Speed T, Spellman PT, DeVries S, Lapuk A, Wang NJ, Kuo WL, Stilwell JL, Pinkel D, Albertson DG, Waldman FM, McCormick F, Dickson RB, Johnson MD, Lippman M, Ethier S, Gazdar A, Gray JW. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin X, David CA, Donnelly JB, Michaelides M, Chandel NS, Huang X, Warrior U, Weinberg F, Tormos KV, Fesik SW, Shen Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:174–179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706585104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamanaka RB, Chandel NS. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Sabatini DM. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:310–322. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh AC, Ruggero D. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:4914–4920. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Cash TP, Jones RG, Keith B, Thompson CB, Simon MC. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel J, McLeod LE, Vries RG, Flynn A, Wang X, Proud CG. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:3076–3085. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor CT. Biochem. J. 2008;409:19–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chua YL, Dufour E, Dassa EP, Rustin P, Jacobs HT, Taylor CT, Hagen T. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:31277–31284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.158485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wouters BG, Koritzinsky M. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:851–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Wise DR, Diehl JA, Simon MC. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:31153–31162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805056200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCloud TC. Molecules. 2010;15:4526–4563. doi: 10.3390/molecules15074526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du L, Mahdi F, Jekabsons MB, Nagle DG, Zhou Y-D. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1868–1872. doi: 10.1021/np100501n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hossain CF, Kim YP, Baerson SR, Zhang L, Bruick RK, Mohammed KA, Agarwal AK, Nagle DG, Zhou Y-D. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;333:1026–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.