Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the risk of and risk factors for a second episode (relapse) among patients with remitted primary anterior uveitis.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Participants

Patients with primary anterior uveitis presenting to one of 4 academic ocular inflammation subspecialty practices achieving remission of the primary episode within 90 days of initial uveitis diagnosis.

Methods

Data were obtained by standardized chart review.

Main outcome measures

Time-to-relapse of anterior uveitis and risk factors for relapse.

Results

102 patients with a first episode of anterior uveitis were seen within 90 days of first-ever uveitis onset and followed for 165 person-years after achieving remission of the initial episode. Most patients were female (60%) and white (78%). Forty patients had a recurrence of anterior uveitis. The incidence of relapse was 24% per person-year (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 17–33%). At 1.5 years after remission, 61% (95% CI: 48–71%) were still in remission. Younger adults had significantly higher relapse risk than middle-aged adults (hazard ratio [18–35 year-old persons vs. 35–55 year-old persons]=2.7, 95% CI: 1.3–6.0).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that many patients with remitted primary anterior uveitis presenting for tertiary uveitis care will relapse. Age in the young adult range was associated with higher risk of relapse. Given the high relapse risk, management of patients with primary anterior uveitis should include an explicit plan for detecting and managing relapses.

Introduction

Uveitis can be a devastating ophthalmic disease, which has been estimated to cause 30,000 new cases of legal blindness annually in the United States1 and up to 10% of cases of blindness.2–4 This disease, which disproportionately affects people in the working age range, has important personal and economic impacts.3 Visual impairment in uveitis may be caused by cataract, glaucoma, retinal scars, macular edema, band keratopathy and various other structural complications of inflammation and its treatment. 5,6 Anterior uveitis is considered to have a better visual prognosis than other forms of uveitis; however it represents up to 92% of all cases of uveitis and therefore contributes significantly to visual loss from uveitis.7

Better knowledge of the risk of and risk factors for relapse following a primary episode of acute anterior uveitis would be valuable to allow physicians to better educate patients about the prognosis of this disease and to guide clinical management decisions such as treatment following remission of the initial attack. However, only limited data regarding the risks of and risk factors for relapse of a first episode of acute primary anterior uveitis are available. Here, we evaluate the risk of and risk factors for relapse in a cohort of patients presenting with primary anterior uveitis, followed from the point of remission of the first episode.

Methods

Study Population

The design of the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Disease (SITE) Cohort Study has been detailed in a prior publication.8 The SITE Cohort Study is a retrospective cohort study of patients with inflammatory eye diseases seen at 5 tertiary academic ocular inflammation centers in the United States. Institutional review board approval was obtained. While previous reports refer to random sampling of a subset of patients at one center, the study group subsequently completed data entry for the previously unsampled patients at that center; the complete database was available for this analysis.

One of the participating centers, which primarily followed a consultative co-management practice pattern, was excluded from this analysis, in order to avoid biases introduced by observation of patients at only a minority of their planned visits wherein there was a greater likelihood of follow-up visits occurring if patients were doing poorly. The other four practices typically either provided a single consultation or directly implemented management over time, minimizing this difficulty amongst the patients followed longitudinally; data from these four centers were used for this report.

All patients who both presented to the participating centers within 90 days of an initial episode of anterior uveitis and who were observed to be in remission within 90 days of initial diagnosis of uveitis were selected for the analysis. Remission was defined as inactivity of uveitis at all visits spanning at least a 90 day interval while using neither corticosteroids nor immunosuppressive drugs9. Thus, patients who did not have sufficient follow-up visits to meet inclusion criteria or who never obtained remission of inflammation during follow-up also were not eligible for this analysis. In order to provide information about primary anterior uveitis, patients with concomitant intermediate and/or posterior uveitis, scleritis, and/or other concomitant ocular inflammatory diseases in addition to their anterior uveitis also were excluded from the analysis. Patients with infectious uveitis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection had been excluded from the parent study.

Data Collection

Data on all the patients had been entered using a data entry system with extensive intrinsic quality control measures, requiring correction of errors in real time, as described in previous reports.8, 10–15 Data evaluated in this analysis included demographic characteristics and diagnosis of systemic inflammatory diseases. Identification of systemic inflammatory diseases associated with ocular inflammatory diseases is a major objective of the participating clinics; 25% of patients had been found to have one of 23 systemic inflammatory diseases (including spondyloarthropathies) in a previous report involving the parent cohort.15 Data on human leukocyte antigen HLA-B27 testing—which had been performed when indicated on the basis of symptoms and clinical findings—also were analyzed.

Patients had been followed longitudinally for relapse of anterior uveitis over the period retrospectively observed. At the participating centers, relapses typically are identified either by observation of relapse of inflammation at scheduled clinic visits or by evaluation of acute symptoms reported to the clinic by the patient. The analysis of relapse was done by-patient, not by-eye. Person-time at risk of relapse was calculated beginning from the point at which remission of anterior uveitis for at least 90 days was first confirmed (beginning from the first visit after at least 90 days of quiescence) because by virtue of the inclusion criteria patients were not at risk of relapse during the period of quiescence required for study entry. Person-time at risk of relapse ended with either the date at which relapse was observed or the date of the last follow-up visit (for patients not observed to have a relapse). Potential risk factors for relapse of anterior uveitis were assessed, including age, sex, race, smoking status, HLA-B27 status, and the presence of systemic inflammatory diseases (as diagnosed by the study ocular inflammation specialists based on history, examination findings, and review of records). In addition to ophthalmology training, all ocular inflammation specialists who had evaluated the patients had completed internal medicine residency, rheumatology fellowship and/or ocular inflammation specialty fellowship training that included systemic inflammatory disease diagnosis as a primary objective of training.

Statistical analysis

Relapse risk was summarized as the incidence per person year (analyzed by patient); a 95% confidence interval (CI) was generated assuming a Poisson distribution. Kaplan-Meier curves were created to evaluate time-to–relapse of anterior uveitis. Potential risk factors for relapse of anterior uveitis were evaluated on the basis of hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs (with 95% CIs) generated using univariate and multivariate Cox regression. The data analyses were performed using SAS v9.1 (SAS Corporation, Cary, NC).

Results

One hundred and two patients who experienced a first episode of primary anterior uveitis followed by remission documented at a participating center within 90 days of initial diagnosis were included in this analysis and followed over 165 person-years at risk for relapse. The median follow up time after remission was 291 days. All visits studied occurred between May 18, 1978 and September 25, 2007. The characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 1 (available at http://aaojournal.org). The majority of patients were female (60%), white (78%) and non-smokers (75%). Thirty patients were ages 34 or younger (29%), the remainder being 35 years or older.

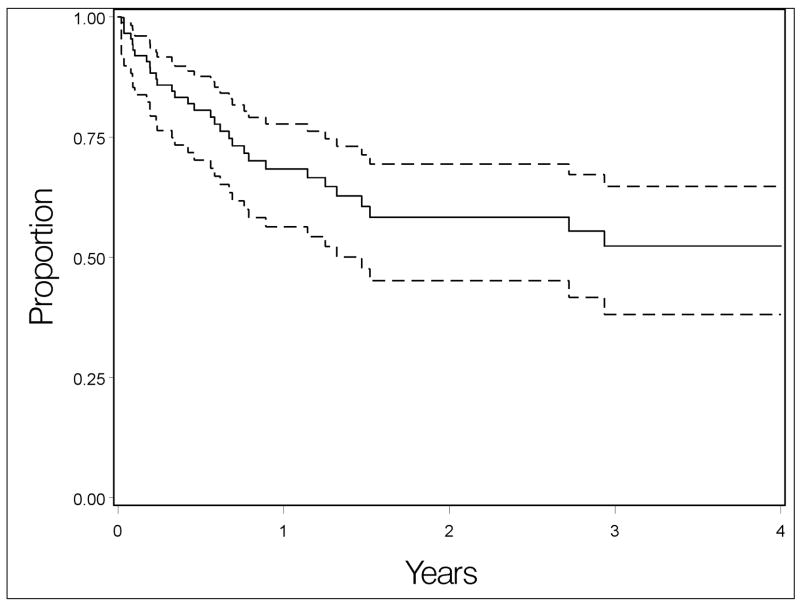

Forty patients (39%) were observed to have a recurrence of anterior uveitis activity during follow up. The incidence rate for relapse of primary anterior uveitis was 24% per person-year (95% Confidence Interval [CI] 17–33%). At 1.5 years after remission, 61% (95% CI: 48–71%) were still in remission (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve depicting overall risk of anterior uveitis recurrence observed in the cohort, with 95% confidence interval bands.

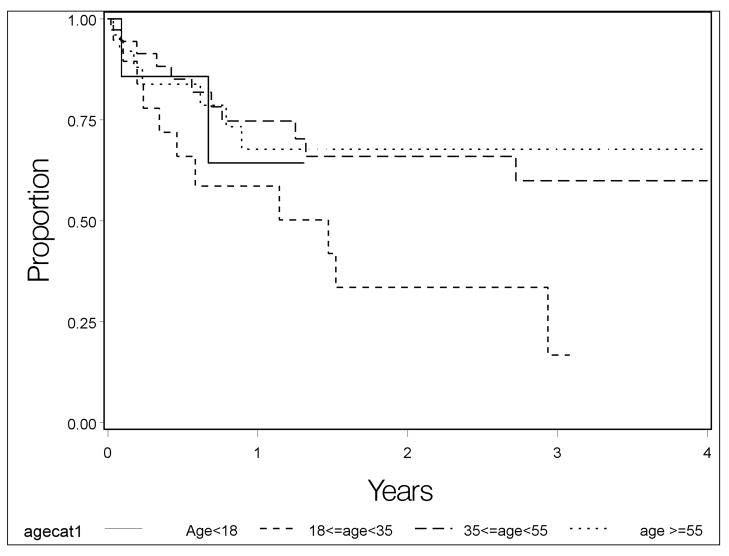

Potential risk factors for recurrence of a first episode of anterior uveitis were evaluated using survival analysis. The crude and adjusted results were similar, so crude hazard ratios (HR) are given here in the text. Recurrence risk varied significantly across age groups (Table 1 which is available at http://aaojournal.org, Table 2, Figure 2); in comparison with the largest group (35–54 years old), the 18–34 year old age group had the highest relapse risk (HR=2.7, 95% CI: 1.3–6.0). The youngest group (<18 years old) also tended to have higher relapse risk (HR=2.0, 95% CI: 0.7–6.4), whereas the group aged 55 years and older had a risk similar to the 35–54 year-old group (HR=1.1, 95% CI: 0.5–2.5). Females and males had similar relapse risk, as did smokers, non-smokers, and former smokers. Neither spondyloarthropathy (HR=1.0, 95% CI: 0.4–2.7), HLA-B27 positive status (HR=1.0, 95% CI:0.5–2.0), nor the presence of both (HR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.1–3.6) were associated with increased relapse risk. Sarcoidosis (HR=1.6, 95% CI: 0.6–4.5) was associated with a higher relapse risk but this was not statistically significant. Other systemic conditions (listed in Table 1 and its footnotes, available at http://aaojournal.org) had been diagnosed infrequently in this group of patients.

Table 2.

Multiple regression analysis for anterior uveitis relapse.

| Characteristic* | Adjusted hazard ratio for recurrence (95 % Confidence Interval) | Overall adjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Age < 18 | 2.1 (0.6 – 6.8) | 0.05 |

| 18 ≤ age<35 | 2.7 (1.2 – 6.1) | 0.05 |

| 35 ≤ age<55 | 1.0 (Reference Group) | |

| Age ≥ 55 | 1.1 (0.4 – 2.6) | 0.05 |

| Sex: Female vs. Male | 1.1 (0.5 – 2.2) | 0.8 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.0 (Reference Group) | |

| Black | 1.5 (0.6 – 3.6) | 0.63 |

| Hispanic or Other | 1.1 (0.4 – 3.3) | 0.63 |

| Spondyloarthropathy | 1.1 (0.4 – 3.3) | 0.91 |

| HLA B27+ | 1.2 (0.5 – 2.7) | 0.66 |

Other characteristics listed in Table 1 which are omitted from Table 2 were not significantly associated with the risk of uveitis relapse and hence were omitted from the multiple regression model.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves depicting risk of anterior uveitis recurrence by age.

Only subjects that were observed to have remission of inflammation (no activity at visits spanning at least a 90 day interval while using neither corticosteroids nor immunosuppressive drugs) were eligible for inclusion. In a sensitivity analysis excluding subjects where the point of first remission and the next visit confirming remission was greater than 6 months results were similar to those presented here (data not shown).

Discussion

These results indicate that the risk of relapse for cases of remitted primary anterior uveitis among patients presenting to tertiary uveitis centers is high, with an estimated rate of relapse of inflammation of 39% at 1.5 years after remission based on this sample. The Kaplan-Meier curve describing the experience of our patients suggests that the risk of first relapse may diminish among patients still free of relapse after two years (see Figure 1), but that even after two years the risk of relapse is not negligible. Given that many patients will experience a uveitis relapse, management of patients with primary anterior uveitis should include a plan as to how relapses will be detected so as to allow prompt treatment. Ophthalmologists cannot see all patients frequently enough to promptly detect all relapses at scheduled exams, and clinical experience suggests that sequelae of uveitis can be avoided in most cases with prompt diagnosis and treatment of relapses. Therefore, patients should be told that the risk of recurrence is high and should be instructed regarding the signs and symptoms of uveitis so that they can recognize relapses and promptly report for care. Patients with fewer symptoms associated with anterior uveitis activity may need to be seen for planned follow-up visits more frequently than patients with easily detectable symptoms.

Prior reports have shown that the mean age of onset of acute anterior uveitis is in the 30’s.16–17 Our analysis suggests that recurrence risk varies by age—a first episode of anterior uveitis in younger adults is more likely to recur. It is not uncommon for more severe cases of a disease to present earlier in life than less severe cases, which may explain this observation. Smoking, which has been observed to increase the risk of relapse of ocular inflammation in general 18–19, was not observed to increase relapse risk specifically in primary anterior uveitis cases.

Spondyloarthropathy and HLA-B27 positive status are well-known to be risk factors for anterior uveitis. 7, 20–21 Prior reports on the risk of recurrence of anterior uveitis have included a mixture of primary and already recurrent uveitis cases; the latter group can be expected to have a higher relapse risk than the former, given that not all primary anterior uveitis cases will relapse. Several studies of such mixed groups of patients have reported a high frequency of recurrence of anterior uveitis in HLA-B27 positive patients with a mean number of attacks ranging from 0.6–3.3 attacks per patient per year of follow up.7, 16, 17, 22, 23 Among studies comparing relapse risk between HLA-B27 positive and negative individuals, one study (performed at a tertiary uveitis center participating in the present study) found a higher frequency of relapses in HLA-B27 positive patients as compared with HLA-B27 negative patients,6 while another study found an equal number of recurrences per eye in HLA-B27 positive and negative patients.16 In our study, HLA-B27 positive status and spondyloarthropathy were not associated with higher risk of relapse, supporting the second result. However, given the available statistical precision our results do not rule out a moderately increased relapse risk in these groups. Although the participating clinics have pursued systemic inflammatory disease diagnoses aggressively throughout their history, it is possible that milder cases of spondyloarthropathy may not have been ascertained in every instance; if spondyloarthropathy in fact is associated with a higher risk of relapse, failure to ascertain these cases may have biased the association toward the null. Our results do not address the frequency of relapse among cases with an established recurrent acute anterior uveitis pattern, which the studies previously cited suggest may be higher among HLA-B27 positive individuals, especially those with both HLA-B27 and a spondyloarthropathy.6, 7, 17

Other systemic disease diagnoses were infrequent among our patients with primary anterior uveitis, limiting our ability to comment on the possible impact of such conditions on relapse risk. Based on the imprecise estimates available, primary anterior uveitis cases associated with sarcoidosis tended to have a higher estimated relapse risk; this preliminary observation requires confirmation in additional studies as the association was non-significant and could well be due to random error.

The strengths of this study included its derivation from a very large parent cohort, which allowed us to look at a relatively large number of primary anterior uveitis cases followed from remission of their index inflammatory event, and the use of quality control efforts to optimize the quality of retrospective data collection. Limitations derive primarily from the retrospective nature of the study. Incomplete follow-up may have led to a mis-estimation of the recurrence rate if patients who did not return for follow-up had a different relapse risk than those who did; if subjects with no recurrences were less likely to return for follow up visits, our overall relapse rate would be overestimated, but still would be high. Relapse was not always identified in the context of scheduled follow-up visits, rather patients were instructed to return for follow up sooner than scheduled visits if they had symptoms of a recurrence. Given that subjects were seen at tertiary centers, cases may have been especially severe and perhaps therefore more prone to relapse, which also would lead to an overestimate of the recurrence rate with respect to a non-tertiary care practice, but which would be representative of tertiary uveitis practices. This problem may be partially mitigated by the exclusion of patients presenting more than 90 days after initial diagnosis, as most patients presenting soon after initial diagnosis are likely to have received their primary eye care at our institutional facilities. In addition, the number of subjects with each of the different systemic inflammatory conditions was relatively small despite the multicenter approach, leading to imprecise estimates of the risk of relapse for these conditions. If systemic conditions were under-diagnosed despite our best efforts—and in truth lead to higher or lower relapse risk—risk ratios associated with these conditions would tend to be biased toward no association, meaning that increases or decreases in risk with these conditions could have been missed by this study. However, none of these limitations are likely to have introduced enough bias so as to affect the primary conclusions that the risk of relapse of primary anterior uveitis is high, and that relapses occur more frequently in younger persons than in adults ages 35 years and higher.

In summary, among cases of primary anterior uveitis presenting to tertiary uveitis centers within 90 days of initial diagnosis and achieving an initial medication-free remission of inflammation within the first 90 days that lasted for at least another 90 days, relapse of uveitis was frequent, occurring in 39% within 1.5 years. Age in the young adult range was associated with an increased relapse risk. Management of these patients should include an explicit plan for detecting relapses—usually based on counseling patients how to respond to new symptoms suggesting uveitis relapse, given that for most cases relapses will be highly symptomatic. However, patients at high risk of relapse for whom obvious uveitic symptoms were not a prominent part of initial presentation may require close monitoring for signs of relapse, particularly in the first two years following presentation of uveitis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported primarily by National Eye Institute Grant EY014943 (Dr. Kempen). Additional support was provided by Research to Prevent Blindness and the Paul and Evanina Mackall Foundation. During part of the conduct of this project, Dr Kempen was an RPB James S. Adams Special Scholar Award recipient, Dr. Thorne was an RPB Harrington Special Scholar Award recipient, and Drs. Jabs and Rosenbaum were Research to Prevent Blindness Senior Scientific Investigator Award recipients. Dr. Levy-Clarke was previously supported by and Dr. Nussenblatt continues to be supported by intramural funds of the National Eye Institute. Dr. Suhler receives support from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the sponsors had any role in the design and conduct of the report; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; nor in the preparation, review, and approval of this manuscript. The authors have the following conflicts of interest, proprietary or financial interests in the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. John Kempen, C, Alcon. C, Lux Biosciences. C, Sanofi-Pasteur. R. Oktay Kaçmaz, E, Allergan. Douglas Jabs, C, Applied Genetic Technologies. C, Alcon. C, Genentech. C, Allergan. C, Genzyme. C, Abbott. C, Novartis. C, Roche. C, GlaxoSmithKline. Eric B. Suhler, S Eyegate. S, Luxbio. S, Genentech. S, Celgene. S, Abbott. Jennifer Thorne, C, Horon evidence development. C Stephen Foster, C/L, Ista. C/L, Lux. C, Novartis.

Online-only material: This article contains online-only material. The following should appear online-only: Table 1.

Meeting presentation: American Academy of Ophthalmology 2010

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nussenblatt RB. The natural history of uveitis. Int Ophthalmol. 1990;14:303–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00163549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darrell RW, Wagner HP, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of uveitis: incidence and prevalence in a small urban community. Arch Ophthalmol. 1962;68:502–14. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1962.00960030506014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suttorp-Schulten MS, Rothova A. The possible impact of uveitis in blindness: a literature survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:844–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.9.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein H. The reported demography and causes of blindness throughout the world. Adv Ophthalmol. 1980;40:1–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanoff M, Duker JS. Opthalmology. 2. St Louis: Mosby; 2004. pp. 1115–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Power WJ, Rodriguez A, Pedroza-Seres M, et al. Outcomes in anterior uveitis associated with HLA-B27 haplotype. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1646–51. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang JH, McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D. Acute anterior uveitis and HLA-B27. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:364–88. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kempen JH, Daniel E, Gangaputra S, et al. Methods for identifying long term adverse effects of treatment in patients with eye diseases: the Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) Cohort Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:47–55. doi: 10.1080/09286580701585892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data: results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaidi A, Ying GS, Daniel E, et al. Hypopyon in patients with uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gangaputra S, Newcomb CW, Liesegang TL, et al. Methotrexate for ocular inflammatory disease. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2188–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kacmaz RO, Kempen JH, Newcomb C, et al. Ocular inflammation in behcet disease: incidence of ocular complications and of loss of visual acuity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:828–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kacmaz RO, Kempen JH, Newcomb C, et al. Cyclosporine for ocular inflammatory disease. Opthalmology. 2010;117:576–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasadhika S, Kempen JH, Newcomb CW. Azathioprine for ocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmology. 2009;148:500–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kempen JH, Daniel E, Dunn JP, et al. Overall and cancer related mortality among patients with ocular inflammation treated with immunosuppressive drugs: retrospective cohort study. Br Med J. 2009;339:b2480. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linssen A, Meenken C. Outcomes of HLA-B27 positive and HLA-B27 negative acute anterior uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:351–61. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothova A, Van Veendaal WG, Linssen A, et al. Clinical features of acute anterior uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:137–45. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galor A, Feuer W, Kempen JH, Kaçmaz RO, Liesegang TL, Suhler EB, Foster CS, Jabs DA, Levy-Clarke GA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Thorne JE. Adverse effects of smoking on patients with ocular inflammation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:813–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.174466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin P, Loh AR, Margolis TP, Acharya NR. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:584–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linssen A, Rothova A, Valkenburg HA. The lifetime cumulative incidence of acute anterior uveitis in a normal population and its relation to ankylosing spondylitis and histocompatibility antigen HLA-B27. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2568–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pathanapitoon K, Suksomboon S, Kunavisarut P, et al. HLA-B27 associated acute anterior uveitis in the University referral centre in north Thailand: Clinical presentation and visual prognosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1448–50. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monnet D, Breban M, Hudry C, et al. Ophthalmic findings and frequency of extraocular manifestations in patients with HLA-B27 uveitis: a study of 175 cases. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:802–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kearney MT, Schwam BL, Lowder C, et al. Clinical features and associated systemic disease of HLA-B27 uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.