Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus aureus synthesizes two siderophores, staphyloferrin A and staphyloferrin B, that promote iron-restricted growth. Previous work on the biosynthesis of staphyloferrin B has focused on the role of the synthetase enzymes, encoded from within the sbnA-I operon, which build the siderophore from the precursor molecules citrate, alpha-ketoglutarate and L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid. However, no information yet exists on several other enzymes, expressed from the biosynthetic cluster, that are thought to be involved in the synthesis of the precursors (or synthetase substrates) themselves.

Results

Using mutants carrying insertions in sbnA and sbnB, we show that these two genes are essential for the synthesis of staphyloferrin B, and that supplementation of the growth medium with L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid can bypass the block in staphyloferrin B synthesis displayed by the mutants. Several mechanisms are proposed for how the enzymes SbnA, with similarity to cysteine synthase enzymes, and SbnB, with similarity to amino acid dehydrogenases and ornithine cyclodeaminases, function together in the synthesis of this unusual nonproteinogenic amino acid L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid.

Conclusions

Mutation of either sbnA or sbnB result in abrogation of synthesis of staphyloferrin B, a siderophore that contributes to iron-restricted growth of S. aureus. The loss of staphyloferrin B synthesis is due to an inability to synthesize the unusual amino acid L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid which is an important, iron-liganding component of the siderophore structure. It is proposed that SbnA and SbnB function together as an L-Dap synthase in the S. aureus cell.

Background

The stimulus of iron limitation is a key sensory trigger for virtually all bacteria. Iron is scarce in the fluids of mammalian hosts, due to rapid oxidation of the soluble ferrous (Fe2+) form to the less soluble ferric (Fe3+) form under aerobic, physiological conditions [1]. Any residual soluble ferric iron is further sequestered through high affinity binding by innate immune proteins such as lactoferrin and transferrin [2]. For many pathogenic microbes, decreasing iron availability leads to the enhanced expression of iron acquisition mechanisms and virulence factors, which frequently play direct roles in liberating iron from host sequestration factors [2-4]. A prevalent component of bacterial iron responses is the secretion of siderophores. These small molecules scavenge residual ferric iron as well as transferrin-bound iron from the extracellular milieu with extremely high affinity and are actively reimported into bacterial cells via dedicated ABC-type transport systems [5,6]. Siderophore assembly pathways fall into two broad classes: nonribosomal peptide synthesis (NRPS) and NRPS-independent siderophore (NIS) synthesis [7,8]. NRPS siderophores are peptidic constructs assembled in a stepwise fashion by large, heterofunctional, multidomain proteins, independently of ribosomes. NIS siderophores are formed via condensation of alternating subunits of dicarboxylic acids with diamines, amino alcohols, and alcohols by sets of synthetase enzymes.

Encoded within the genome of S. aureus are two loci directing the production of NIS-type siderophores. The sfaABCD locus encodes for proteins involved in biosynthesis and secretion of staphyloferrin A, a molecule also produced by the majority of less pathogenic coagulase-negative staphylococci [9-12]. This metabolite is assembled from one unit of the nonproteinogenic amino acid D-ornithine and two units of citrate; the staphyloferrin A biosynthetic pathway was recently established in an elegant study [10]. The sbnABCDEFGHI operon encodes for biosynthesis and secretion of staphyloferrin B. This siderophore has been identified in S. aureus and a few species of coagulase-negative staphylococci, and in the Gram-negative genera Ralstonia and Cupriavidus [13-16]. However, based on early studies by Haag et al. [16] and recent staphylococcal genome data, staphyloferrin B may also be produced by other coagulase-positive staphylococci other than S. aureus. Staphyloferrin B is comprised of one unit each of citric acid, 1,2-diaminoethane, alpha-ketoglutaric acid, and the nonproteinogenic amino acid L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (L-Dap) [15-17]. These precursors are condensed by NIS synthetase enzymes SbnC, SbnE, and SbnF, with modification of an intermediate metabolite by decarboxylase SbnH [17]. Inactivation of staphyloferrin B biosynthesis (via chromosomal deletion of a siderophore synthetase) was previously shown to reduce the virulence of S. aureus in a mouse infection model [14], which underscores the contribution of specialized iron uptake mechanisms to pathogenesis. In addition to the characterized functions of SbnCEFH in staphyloferrin B biosynthesis, the sbn operon also encodes several auxiliary enzymes predicted to be involved in generation of staphyloferrin B precursors or substrates that would be fed to the NIS synthetases. Of interest are the first two genes sbnA and sbnB, which encode proteins with a yet undiscovered role in staphyloferrin B biosynthesis. Furthermore, it is intriguing that SbnA and SbnB share sequence homology to the enzymes VioB and VioK, respectively, of the viomycin assembly pathway in Streptomyces sp. [18]. Like staphyloferrin B, the antibiotic viomycin molecule also contains L-Dap as a structural component. It was hypothesized by Thomas et al. [18] that VioB (homologous to SbnA) catalyzes a β-substitution replacement reaction to generate L-Dap from (O-acetyl-)L-serine using ammonia as a nucleophile. The source of this ammonia would come from the activity of VioK, which like SbnB, shares sequence identity with bacterial ornithine cyclodeaminases that would catalyze the cyclization of L-Orn to L-Pro with concomitant release of ammonia. Therefore, it is probable that VioK and VioB (or SbnA and SbnB) function synergistically as an L-Dap synthase. The production of L-Dap is a critical process because the molecule is used twice per mole of staphyloferrin B [17]. Specifically, both prochiral carboxyl groups of citrate are condensed onto a molecule of L-Dap as catalyzed by the synthetases SbnE and SbnF [17].

In this study, through a series of genetics-based experiments, we propose that the generation of L-Dap in S. aureus is a coupled function of enzymes SbnA and SbnB, whose activity is essential for the downstream biosynthesis of the siderophore staphyloferrin B.

Methods

Strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains, plasmids and oligonucleotides used throughout the study are described in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth, with the following antibiotic concentrations used for selection of plasmids: kanamycin (30 μg/mL), ampicillin (100 μg/mL), erythromycin (300 μg/mL). S. aureus strains were grown in tryptic soy broth for genetic manipulations, with the following antibiotic concentrations used for selection of strains bearing plasmids or chromosomal resistance cassettes: erythromycin (3 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (5 μg/mL), tetracycline (4 μg/mL). For characterization of growth phenotypes, S. aureus strains were grown in Tris-minimal succinate (TMS) [19] broth. TMS culture medium was pretreated with Chelex-100 resin (Bio-Rad) for 24 h at 4°C with 10% (wt/vol) Chelex-100 resin prior to autoclaving. Some micronutrients were added postautoclave. Further culture amendments are detailed below. All media were made with water purified through a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA). All glassware was treated overnight in 0.1 M HCl and rinsed thoroughly with Millipore-filtered water to remove residual contaminating iron.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Reagent | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Φ80 dLacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rk- mk+) supE44 relA1 deoRΔ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | Promega |

| S. aureus | ||

| RN4220 | rk- mk+; accepts foreign DNA | [20] |

| RN6390 | Prophage-cured wild-type strain | [21] |

| Newman | Wild-type clinical isolate | [22] |

| H803 | Newman sirA::Km; KmR | [30] |

| H1665 | Newman Δsfa::Km; KmR | [9] |

| H1666 | Newman Δsbn::Tet Δsfa::Km; TetR KmR | [9] |

| H1262 | Newman Δhts::Tet; TetR | [9] |

| H1497 | Newman sirA::Km Δhts::Tet; TetR KmR | [9] |

| H2131 | Newman sbnA::Tc ΔsfaABCsfaD::Km | This study |

| H1718 | Newman sbnB::Tc ΔsfaABCsfaD::Km | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | E. coli cloning vector; CmR | ATCC |

| pALC2073 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector; ApR CmR | [26] |

| pAUL-A | Temperature-sensitive S. aureus suicide vector; EmR LcR | [25] |

| pDG1514 | pMTL23 derivative carrying tetracycline resistance cassette; ApR | [24] |

| pFB5 | pALC2073 derivative carrying sbnA; CmR | This study |

| pSED52 | pALC2073 derivative carrying sbnB; CmR | This study |

| Oligonucleotides* | ||

| Cloning of sbnA into pBC SK+ | ||

| sbnA5'-SacI | 5' TGAGCTCGATTCTGTAGGGCAAACACC 3' | |

| sbnA3'-KpnI | 5' TTGGTACCTCTAAGTAACGATCGCCTCG 3' | |

| Amplification/cloning of a tetracycline resistance cassette from pDG1513 | ||

| Tet5'-NsiI | 5' TTGTATATGCATACGGATTTTATGACCGATGA 3' | |

| Tet3' | 5' TGTGTGGAATTGTGAGCGGATAAC 3' | |

| Cloning of sbnA into pALC2073 | ||

| sbnA5'-XhoI | 5' TTTCTCGAGATTTTAAATTTGAGGAGGAA 3' | |

| sbnA3'-EcoRI | 5' TTTGAATTCCCACATAAACTTGTGAATGATT 3' | |

| Cloning of sbnB into pACYC184 | ||

| sbnB5'-BamHI | 5' TTGGATCCTAGTTTATTCAGATACATGG 3' | |

| sbnB3'-BamHI | 5' TTGGATCCTGTCCCAATATTTTGTTGTT 3' | |

| Cloning of sbnB into pALC2073 | ||

| sbnB5'-EcoRI | 5' TTGAATTCTCAAGTGATCCATGTAGATG 3' | |

| sbnB3'-EcoRI | 5' TTGAATTCCAATTCCGGCTATATCTTCA 3' | |

* underlined sequences in oligonucleotides denote restriction sites

DNA and PCR preparation and purification

Plasmid DNA was isolated from bacteria using Qiaprep mini-spin kits (Qiagen), as directed. S. aureus cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in P1 buffer amended with 50 mg/mL lysostaphin (Roche Diagnostics) prior to addition of lysis buffer P2. Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, Klenow fragment, and PwoI polymerase were purchased from Roche Diagnostics. Pfu Turbo polymerase was purchased from Stratagene and oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. For all PCR reactions, genomic template was from S. aureus strain Newman.

Genetic manipulation and construction of S. aureus mutants

All extrachromosomal genetic constructs were created in E. coli strain DH5α and then electroporated into the restriction-deficient S. aureus strain RN4220 [20] prior to subsequent passage into other S. aureus genetic backgrounds. Chromosomal replacement alleles (namely sbnA::Tc and sbnB::Tc) were generated in strain RN6390 [21] and transduced into the Newman [22] background using phage 80α, similar to previously described methods [9,23]. The sbnA::Tc and sbnB::Tc mutant alleles and vectors for complementing these mutations in trans were generated using methodologies previously described [9,23].

To create an inactivation allele for sbnA, the sbnA gene was PCR amplified from the chromosome of S. aureus strain Newman using primers with engineered SacI and KpnI restriction sites, and cloned into vector pBC SK+. A tetracycline resistance cassette was PCR amplified from vector pDG1514 [24], digested with restriction enzymes NsiI and PstI, and ligated into a unique NsiI restriction site in sbnA; this allele was excised and ligated into temperature-sensitive suicide shuttle vector pAUL-A [25] using restriction enzymes KpnI and SacI, then integrated via double homologous recombination into the S. aureus RN6390 chromosome. The mutation was transduced to S. aureus Newman Δsfa (strain H1665) [9] for use in this study. To generate a complementation vector, sbnA was PCR-amplified using primers with engineered XhoI and EcoRI restriction sites and cloned directly to pALC2073, creating plasmid pFB5.

To create an inactivation allele for sbnB, the sbnB gene was PCR-amplified from the chromosome of S. aureus strain Newman using primers with engineered BamHI sites but cloned as a blunt-ended PCR product to vector pACYC184 digested with EcoRV. A tetracycline resistance cassette was excised from vector pDG1514 [24] with restriction enzymes NsiI and PstI and ligated into a unique PstI restriction site in sbnB within pACYC184; this allele was excised and ligated into temperature-sensitive suicide shuttle vector pAUL-A using restriction enzyme BamHI, then integrated via double homologous recombination into the S. aureus RN6390 chromosome prior to transduction into S. aureus Newman Δsfa (strain H1665) for use in this study. To generate a complementation vector, sbnB was PCR-amplified using primers with engineered EcoRI restriction sites and cloned directly to pALC2073 [26], creating plasmid pSED52.

Growth assays

S. aureus growth curves were generated using a Bioscreen C plate reader (Oy Growth Curves, Finland). Prior to plate inoculation, strains were grown in glass tubes for 12 h in TMS broth and then subcultured and grown for 12 h in TMS broth containing 100 μM 2,2'-dipyridyl (Sigma). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice in sterile saline solution, and diluted 1:100 into 200- or 250-μl chelex-treated TMS. Amendments to culture media included 10 μM human holotransferrin (60% iron saturated) (Sigma), 5 mM L- or D-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (Iris Biotech GmbH), 5 mM L-ornithine (Sigma), 5 mM L-alanine, 5 mM O-acetyl-L-serine (Sigma), 5 mM L-proline (Sigma), or FeCl3 (at 10 or 100 μM). Appropriate antibiotics at the concentrations stated above were included to maintain plasmid selection for complementation experiments. Plates were incubated with constant shaking at medium amplitude. Optical density (OD) was recorded every 15 min, although for graphical clarity, figures have been edited to display values every 2 h.

Siderophore quantification

Quantification of siderophore output from S. aureus strains was performed by testing the iron-binding activity of culture supernatants, using a chrome azurol S (CAS) shuttle solution as described previously [9,27]. Supernatant siderophore units were normalized to culture optical density.

Siderophore preparations

Siderophore concentrates were prepared by growing S. aureus strains with aeration in TMS with 0.1 μM EDDHA. Culture supernatants were harvested at 15 and 40 hours after initial culturing. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and supernatants were lyophilized. The freeze-dried supernatant was extracted with methanol (one-fifth the original supernatant volume), and then passed through a Whatman No. 1 filter paper to remove insoluble material followed by rotary evaporation. The methanol-extracted material was solubilized in water to 5% of the original supernatant volume. The resulting preparations were stored at -20°C.

Siderophore plate-disk diffusion assays

Siderophore growth promotion assays were performed essentially as described [9]. Briefly, S. aureus strains were seeded into TMS agar (1 × 104 cells ml-1) containing 10 μM EDDHA. Ten-μL aliquots of culture supernatant concentrates (as prepared above) were added to sterile paper disks which were then placed onto the TMS agar plates. Growth promotion was quantified by measuring the diameter of growth around the disc after 36 h at 37°C.

Computer analyses

DNA sequence analysis, oligonucleotide primer design and sequence alignments were performed either using programs available through NCBI or using Vector NTI Suite software package (Informax, Bethesda, MD). Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 4.0.

Results

The S. aureus sbn operon contains genes predicted to encode L-Dap biosynthesis enzymes

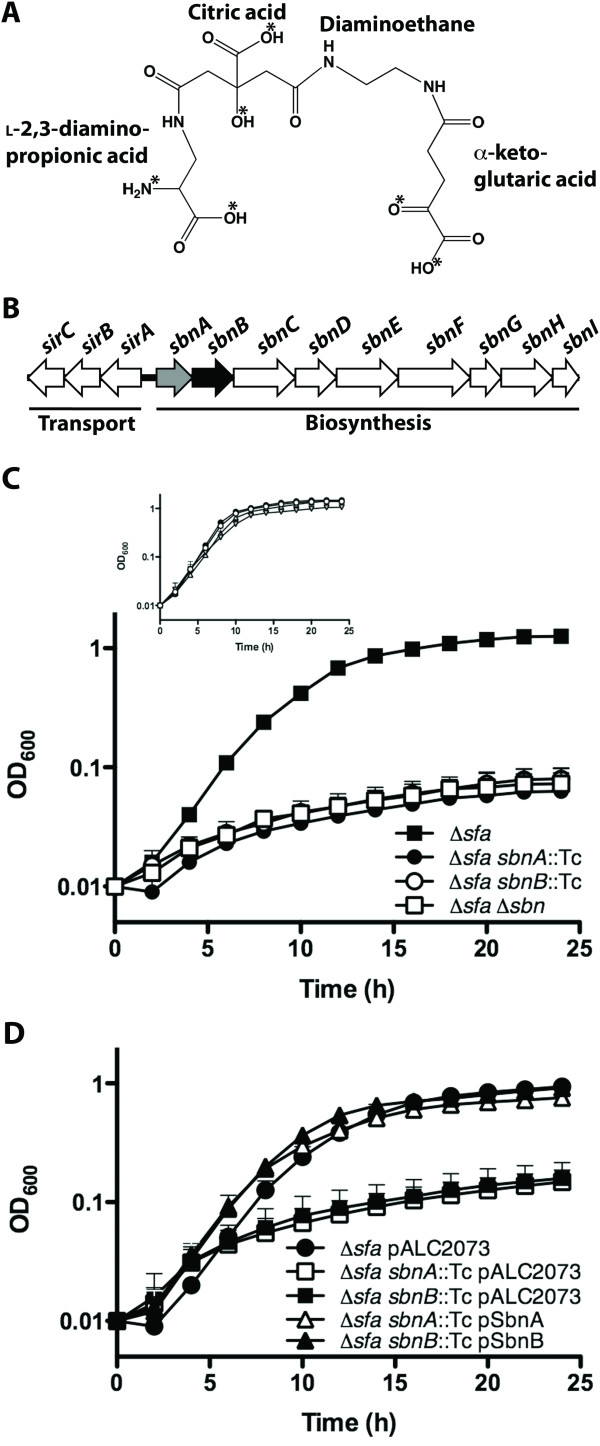

Original studies on the structural elucidation of staphyloferrin B revealed that it contained citric acid, α-ketoglutaric acid (α-KG), 1,2-diaminoethane (Dae), and L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid (L-Dap) [15] (Figure 1A). The unusual nonproteinogenic amino acid L-Dap serves a critical role for the siderophore in terms of iron-coordination, since a carboxyl group oxygen and the nitrogen atom on the primary amine of L-Dap contribute two of the six iron-ligands used to obtain the distorted octahedral geometry in the ferric-staphyloferrin B complex [28] (Figure 1A). In the proposed biosynthetic pathway, L-Dap is twice incorporated into the staphyloferrin B molecule, as the amine nucleophilic substrate for the type A and type C NIS synthetases SbnE and SbnF, respectively [17]. While SbnE condenses the first molecule of L-Dap to citrate, the action of the decarboxylase SbnH removes the carboxyl group from the L-Dap residue to give rise to the Dae portion of staphyloferrin B [17]. SbnF then condenses a terminal L-Dap onto a citryl-Dae intermediate within the staphyloferrin B structure [17]. Since L-Dap plays such a pivotal role in iron-coordination for staphyloferrin B, and since the biosynthesis of this siderophore requires two units of L-Dap per unit of staphyloferrin B, we were interested in elucidating the genetic requirement for L-Dap biosynthesis in S. aureus.

Figure 1.

SbnA and SbnB are essential for synthesis of staphyloferrin B in S. aureus. A) Chemical structure of staphyloferrin B with fundamental components labeled. Asterisks indicate ligands responsible for the octahedral coordination of iron. B) Within the sir-sbn genetic locus, the focus of this study is the characterization of mutations in sbnA (highlighted grey) (encoding a putative cysteine synthase) and sbnB (highlighted in black) (encoding a putative ornithine cyclodeaminase). Together, the products of these two genes are hypothesized to be an L-Dap synthase. C) S. aureus mutants were grown in chelex 100-treated TMS medium containing 10 μM holo-transferrin. In the Δsfa genetic background, growth in this medium is dependent on the production of the siderophore staphyloferrin B. Supplementation of the medium with FeCl3 allows for equivalent growth for all strains (inset). D) The growth impairment exhibited by S. aureus sbnA or sbnB mutants, in the Δsfa genetic background, can be restored upon complementation in trans with a wild-type copy of the corresponding gene. Plasmid pALC2073 is the vehicle control.

S. aureus possesses a nine-gene sbn operon with an adjacent sir operon; these operons encode proteins that function in staphyloferrin B biosynthesis and transport, respectively [17,23,29,30] (Figure 1B). SbnC, SbnE, SbnF, and SbnH have been previously described as the core enzymes involved in staphyloferrin B biosynthesis [17], however the function of several gene products in the sbn operon remain to be resolved. Since L-Dap is such a critical component of staphyloferrin B, we reasoned that the biosynthesis of this molecule must be intrinsic to the sbn operon and that L-Dap biosynthesis is likely to occur concurrently with the activity of the rest of the Sbn enzymes. The first two genes in the sbn operon are sbnA and sbnB (Figure 1B) which, through simple NCBI BLAST searches, reveal that they share similarity with cysteine synthases (Table 2) and L-ornithine cyclodeaminases (Table 3), respectively. However, further bioinformatic analyses suggested that genes homologous to sbnA and sbnB fall under a new family of enzymes currently dubbed "PLP_SbnA_fam" and "dehyd_SbnB_fam", respectively, suggesting that they may carry out functions distinct from the above mentioned enzyme activities. Furthermore, close homologs of these two genes consistently appear adjacent to one another or are genetically fused into a single polypeptide (see Table 4) with the presumed purpose of functioning together to create a biosynthetic precursor. Of particular note are other organisms, in addition to S. aureus, that are predicted to produce staphyloferrin B based on the similarity and gene organization of their biosynthetic operons to that of the S. aureus sbn operon. Furthermore, genes homologous to sbnA and sbnB are also found in biosynthetic gene clusters responsible for producing the characterized antibiotics zwittermicin A [31,32], viomycin [18], and dapdiamides [33,34] that all contain L-Dap (Table 2). In support of the presumed role of SbnA and SbnB in L-Dap synthesis, Thomas and colleagues [18] earlier proposed that the enzymes VioB (SbnA homologue) and VioK (SbnB homologue) were involved in production of L-Dap for viomycin synthesis. Therefore, it appears that homologues of sbnA and sbnB are widely distributed across biosynthetic gene clusters, whose enzymes synthesize molecules for which L-Dap is featured as a structural component.

Table 2.

List of SbnA homologs

| Organism | Similar Proteina | PDB ID | Identity (%) |

Similarity | E-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Cysteine synthase | 1z7w | 33 | 0.500 | 0 |

| Homo sapiens | Cystathionine beta-synthase | 1jbq | 30 | 0.498 | 0 |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | Serine racemase | 1v71 | 17 | 0.202 | 0 |

| Escherichia coli | Biosynthetic threonine deaminase | 1tdj | 18 | 0.255 | 0 |

| Homo sapiens | L-serine dehydratase | 1p5j | 20 | 0.249 | 0 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Threonine synthase | 2d1f | 19 | 0.279 | 0 |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | Tryptophan synthase beta chain 1 | 1v8z | 22 | 0.231 | 0 |

| Pyrococcus horikoshii | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase | 1j0a | 19 | 0.123 | 0 |

aOnly top hit, using HHPred, for each class of enzyme is shown

Table 3.

List of SbnB homologs

| Organism | Homologous Proteina | PDB ID | Identity (%) |

Similarity | E-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaeoglobus fulgidus | Alanine dehydrogenase | 1omo | 32 | 0.543 | 0 |

| Homo sapiens | MU-crystallin homolog | 2i99 | 24 | 0.381 | 0 |

| Pseudomonas putida | Ornithine cyclodeaminase | 1x7d | 21 | 0.352 | 0 |

| Thermoplasma volcanium | Glutamyl-tRNA reductase | 3oj0 | 15 | 0.312 | 3e-19 |

| Geobacillus kaustophilus | Shikimate 5-dehydrogenase | 2egg | 13 | 0.113 | 1.4e-9 |

aOnly top hit, using HHPred, for each class of enzyme is shown

Table 4.

List of bacteria, not including S. aureus, containing transcriptionally-linked sbnA/sbnB homologs

| Organism | Homologous Gene ID (SbnA/SbnB) |

Similarity (% SbnA/%SbnB) |

E-Value (SbnA/SbnB) |

Predicted gene cluster product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius HK10-03 | spint_0334/spint_0335 | 90/91 | 2e-149/6e-161 | Staphyloferrin B |

| Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 | rmet_1117/rmet_1116 | 75/71 | 1e-102/2e-97 | Staphyloferrin B |

| Ralstonia solanacearum GMT1000 | cysK2/rsp0418 | 76/79 | 8e-100/2e-118 | Staphyloferrin B |

| Shewanella denitrificans OS217 | sden_0590/sden_0589 | 73/75 | 6e-100/2e-109 | Staphyloferrin B |

| Methylobacterium nodulans ORS 2060 | mnod_6948/mnod_6949 | 71/72 | 9e-91/2e-104 | Staphyloferrin B |

| Acinetobacter sp. DR1 | aole_07120/aole_07115 | 76/74 | 4e-84/6e-104 | Staphyloferrin B?** |

| Clostridium cellulovorans 743B | clocel_3151/clocel_3150 | 64/55 | 4e-65/7e-39 | Unknown |

| Streptomyces griseus subsp. Griseus NBRC 13350 | sgr_2592/sgr_2591 | 57/52 | 1e-56/9e-34 | Unknown NRPS product |

| Pantoea agglomerans | ddaA/ddaB | 56/53 | 5e-57/3e-32 | Dapdiamide antibiotic |

| Bacillus thuringiensis serovar kurstaki YBT-1520 | zwa5A/zwa5B | 63/55 | 5e-72/3e-48 | Zwittermicin A antibiotic |

| Streptomyces vinaceus | vioB/vioK | 52/47 | 1e-49/3e-31 | Viomycin antibiotic |

| Acidobacterium capsulatum ATCC 51196 | acp_1153* | 61/44 | 5e-73/1e-26 | Unknown polyketide-NRPS product |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 | pspto_2960* | 59/49 | 4e-64/4e-34 | Unknown |

| Paenibacillus sp. JDR-2 | pjdr2_5192/pjdr_5191 | 63/49 | 5e-76/1e-37 | Unknown |

| Herpetosiphon aurantiacus ATCC 23779 | haur_1863/haur_1864 | 64/49 | 8e-77/3e-35 | Unknown NRPS product |

*Indicates fusion of sbnA and sbnB homologs into one coding region

**Known gene required for staphyloferrin B biosynthesis (sbnH homolog) is missing from operon

Both sbnA and sbnB are required for staphyloferrin B biosynthesis in S. aureus

The goal of this study was to elucidate the requirement for sbnA and sbnB in staphyloferrin B synthesis in S. aureus, specifically with regard to their presumed role in providing a source of L-Dap in the cell. Under iron-limiting growth conditions, S. aureus synthesizes two siderophores, named staphyloferrin A and staphyloferrin B. As we have previously demonstrated, both siderophores play a vital role in acquisition of iron from human holo-transferrin [23]. Moreover, because of functional redundancy, when either the biosynthetic gene cluster for staphyloferrin A (sfa) or staphyloferrin B (sbn) is inactivated alone (i.e. leaving the other intact in the S. aureus cell), the resulting mutants do not display a growth deficit phenotype when human holo-transferrin is provided as the sole iron source. Therefore, the simplest manner in which to study the function of specific genes within the sbn operon was to use a strain that was deficient in its ability to synthesize staphyloferrin A; as such, all experiments outlined in this study were performed in a S. aureus sfa deletion background.

With holo-transferrin as the sole iron source in the bacterial growth medium, an S. aureus Δsfa mutant was capable of growth to an optical density in excess of 1.0 within twenty-four hours (Figure 1C), in agreement with earlier studies [23]. This growth was dependent on an intact sbn gene cluster (and, hence, staphyloferrin B production) since the Δsfa Δsbn mutant did not grow above an optical density of 0.1 over the same time period. These growth kinetics were identical to those of S. aureus Δsfa sbnA::Tc and S. aureus Δsfa sbnB::Tc mutants (Figure 1C), suggesting abrogation of staphyloferrin B production in the absence of either sbnA or sbnB. Electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry was used to confirm that staphyloferrin B was present in the spent culture supernatant of the Δsfa strain, yet was absent in the spent culture supernatants of the S. aureus Δsfa sbnA::Tc and S. aureus Δsfa sbnB::Tc strains (data not shown). Importantly, the ESI-MS data were obtained from cultures grown in TMS without added transferrin; this medium is iron-limited but not so much as to completely abrogate growth of siderophore-deficient strains. In order to ensure that the mutant growth deficiencies were not due to pleiotropic effects as a result of the introduction of alternate genetic mutations and that growth, or lack thereof, is solely dependent on iron accessibility, we supplemented each strain with FeCl3; this resulted in the growth rescue of all strains (Figure 1C, inset). Moreover, mutants carrying insertions in sbnA and sbnB were fully complemented by expressing the wild-type version of the genes in trans; complemented strains were able to reach a final biomass comparable to the isogenic S. aureus Δsfa parental strain (Figure 1D).

Supplementation of growth media with L-Dap bypasses sbnA and sbnB mutations, allowing for restored staphyloferrin B production in S. aureus

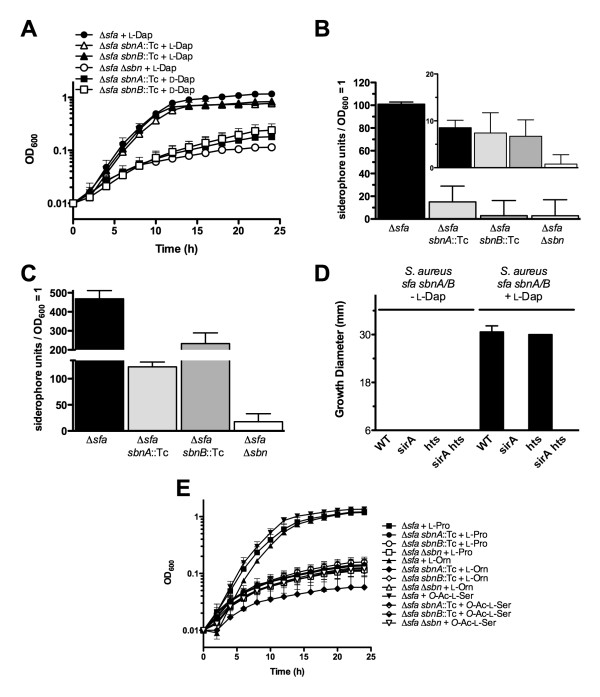

If SbnA and SbnB are involved in the production of L-Dap for staphyloferrin B biosynthesis, then the growth deficit phenotype displayed by S. aureus Δsfa sbnA::Tc and S. aureus Δsfa sbnB::Tc mutants (Figure 1) should be restored when L-Dap is supplemented in the culture medium, since presence of this molecule would bypass the need for the activities of SbnA or SbnB in siderophore production. Accordingly, as shown in Figure 2A, the iron-restricted growth of sbnA and sbnB mutants is restored equivalent to that of staphyloferrin B-producing cells when the culture medium of the sbnA and sbnB mutants is supplemented with L-Dap, but not D-Dap. This is in agreement with the fact that only the L-isomer of Dap is present in the final structure of the staphyloferrin B molecule [15,16,28]. Providing L-Dap to the complete staphyloferrin-deficient mutant (Δsfa Δsbn) did not allow iron-restricted growth, suggesting that growth restoration of sbnA and sbnB mutants by L-Dap is a result of this precursor being incorporated into a functional siderophore in the presence of other staphyloferrin B biosynthesis enzymes (Figure 2A). This result shows that provision of L-Dap to either sbnA or sbnB mutants allowed the bypass of the requirement for these genes in staphyloferrin B biosynthesis, which strongly supports the hypothesis that sbnA and sbnB function together in a direct role in L-Dap synthesis.

Figure 2.

Supplementation of culture medium with L-Dap allows S. aureus sbnA and sbnB mutants to overcome the block in synthesis of staphyloferrin B. A) Bacterial growth curves in chelex 100-treated TMS containing 10 μM holo-transferrin as the sole iron source, with the indicated supplements. B) Siderophore quantification from culture supernatants of iron-starved S. aureus mutants via CAS assay (see Materials and Methods). The inset graph represents culture supernatants from identical strains but grown in medium supplemented with FeCl3. Siderophore units are normalized to culture density. C) Same as in B) except culture media was supplemented with L-Dap. D) Siderophore-disk diffusion assays. Culture supernatants to be tested were derived from S. aureus Δsfa sbnA::Tc or Δsfa sbnB::Tc strains cultured in medium supplemented with, or without, L-Dap, as indicated, and were spotted onto sterile paper disks before being placed onto TMS agar plates seeded with S. aureus wild-type and siderophore transport mutants, as indicated. Plate disk bioassay is described in Materials and Methods. E) Bacterial growth curves for cultures of S. aureus Δsfa sbnA::Tc and S. aureus Δsfa sbnB::Tc mutants in chelex 100-treated TMS medium containing 10 μM holo-transferrin as the sole iron source, where the medium was supplemented with various hypothesized L-Dap synthase substrates and by-products from Fig. 3, scheme A.

Since the iron-restricted growth of S. aureus Δsfa sbnA::Tc and S. aureus Δsfa sbnB::Tc mutants was restored in the presence of L-Dap, we hypothesized that this was due to the mutants' renewed ability to synthesize staphyloferrin B. To verify this, we performed a chrome azurol S (CAS) assay on concentrated and methanol-extracted culture supernatants of several mutant derivatives of S. aureus Δsfa (grown under iron starvation) to quantify their siderophore production (Figure 2B and 2C). Consistent with the growth phenotype illustrated in Figure 2A, amendment of growth media with L-Dap allowed siderophore production by S. aureus Δsfa sbnA::Tc and Δsfa sbnB::Tc (Figure 2C). Interestingly, supplementation of the parental strain (Δsfa) with L-Dap enhanced the level of staphyloferrin B output by approximately five-fold (Figure 2C cf. Figure 2B).

As a final method to demonstrate that the siderophore secreted by S. aureus Δsfa sbnA::Tc or Δsfa sbnB::Tc mutants, in media supplemented with L-Dap, was indeed staphyloferrin B, we performed plate-disk growth promotion assays by spotting culture supernatants onto sterile paper disks that were then placed onto TMS agar seeded with various S. aureus siderophore transport mutants (Figure 2D). Only culture supernatants from S. aureus sbnA::Tc or sbnB::Tc mutants that were fed L-Dap promoted the growth of seeded S. aureus Δhts and its isogenic wild-type strain, but strains containing a mutation in the sirA gene (encoding the receptor lipoprotein for staphyloferrin B) did not grow. Moreover, no growth-promoting siderophore was produced by sbnA or sbnB mutants grown in media lacking L-Dap (Figure 2D). LC-ESI-MS/MS was used for confirmation of staphyloferrin B presence in methanol-extracted culture supernatants of complemented mutants (data not shown); spectra were as published previously [17]. When iron-restricted growth media were supplemented with several other molecules that were predicted substrates or byproducts of an SbnA-SbnB reaction (e.g. L-ornithine, L-proline, and O-acetyl-L-serine) according to the models illustrated in Figure 3, scheme A, we noted that none rescued the iron-restricted growth of sbnA or sbnB mutants in the Δsfa background (Figure 2E). This leads us to conclude that none of these molecules can be modified into L-Dap by alternative S. aureus enzymes.

Figure 3.

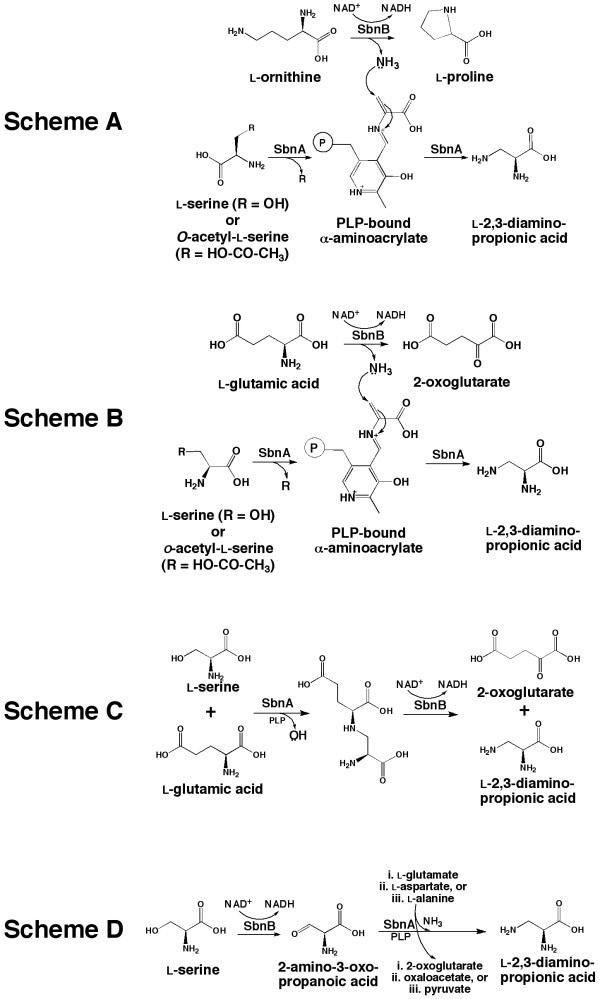

Proposed schemes for SbnA- and SbnB-dependent synthesis of L-Dap. Scheme A is adapted from Thomas et al. [18] for which the functions of SbnA and SbnB are analogous to the proposed functions VioB and VioK, respectively. The proposed functions of SbnA in schemes B-D remain as a β-replacement enzyme while SbnB is proposed to be an NAD+-dependent dehydrogenase of the indicated amino acid.

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated, through a series of genetics-based experiments, that the S. aureus sbnA and sbnB genes are necessary for staphyloferrin B production. We have also shown that S. aureus mutations in sbnA and sbnB are fully complementable in trans by both wild-type copies of each gene as well as through feeding of the molecule L-Dap itself, leading to the renewed production of the staphyloferrin B molecule. The data support the contention that the enzymes SbnA and SbnB function synergistically as a L-Dap synthase, catalyzing the first committed biosynthetic step towards staphyloferrin B synthesis in S. aureus. Overall, this is the first study that simultaneously investigates the roles of both genes encoding a cohesive L-Dap synthase.

The L-Dap molecule is a very unusual and rare amino acid. It is non-proteinogenic but it is often found structurally associated with secondary metabolites such as antibiotics (Table 4). To our knowledge, staphyloferrin B represents the only characterized siderophore that contains L-Dap as part of its structure (Figure 1A). The experiment shown in Figure 2A also reinforces the fact that only L-Dap, and not D-Dap, is incorporated into staphyloferrin B. This is in agreement with initial structural elucidation studies [15], the high resolution crystal structure of the siderophore [28], as well as enzymatic recognition of L-Dap as a substrate by staphyloferrin B NIS synthetases [17]. The only siderophore with a component similar to L-Dap in its structure is achromobactin from Pseudomonas syringae [35], which has an overall structure and biosynthetic pathway that is very similar to that of staphyloferrin B. In place of L-Dap, achromobactin contains L-2,4-diaminobutyric acid which is condensed onto a unit of citrate and α-KG at both amino groups. L-2,4-diaminobutyric acid may be synthesized by a putative aminotransferase (AcsF) that is also encoded within the achromobactin biosynthetic gene cluster. In the case of achromobactin, synthesis of this diamino acid substrate requires only one enzyme as opposed to the two enzymes required for synthesis of L-Dap. Biochemical characterization of AcsF, along with its substrate specificity, awaits further investigation. Why some siderophore biosynthetic systems have evolved to select one diamino acid over another is an intriguing biological question.

Based on bioinformatics and the emerging diversity of members of the OCD enzyme family, the S. aureus SbnB enzyme likely does not contribute to proline production, and hence would not recognize L-ornithine as a substrate. In agreement with this hypothesis, under the experimental conditions of Li et al. [36] in testing S. aureus for proline synthesis, they could not attribute the production of L-proline to SbnB, but rather L-proline production was solely dependent on the pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase pathway; it should be noted, however, that these experiments did not test whether sbnB was responsible for proline synthesis under low-iron growth conditions and thus do not completely eliminate the possibility that SbnB has OCD activity. The exact biochemical reactions catalyzed by SbnA and SbnB (and homologs) await detailed investigation.

SbnA and SbnB are likely functioning together as an L-Dap synthase and perhaps the mechanism is that originally proposed by Thomas and colleagues [18] for VioB and VioK with regards to viomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces (Figure 3, scheme A). In this scheme for L-Dap synthesis, VioK (or SbnB) acts as an L-ornithine cyclodeaminase (based on sequence similarity to an OCD [1X7D]) that will convert L-Orn to L-Pro with the concomitant release of ammonia. The released ammonia is picked up by VioB (or SbnA) to be used as a nucleophile for the β-replacement reaction on (O-acetyl-) L-serine, thus generating L-Dap. The reaction catalyzed by VioB (or SbnA) is modeled after homologous cysteine synthases which use a sulfide group for β-replacement reactions to generate cysteine [18]. Therefore, the action of VioB, or SbnA, would appear to be an amidotransferase in this reaction scheme.

However, more recent bioinformatic and phylogenetic analyses of these enzymes suggest that the mechanism of L-Dap synthesis may be quite different from that just described. This is especially true for SbnB, which is more closely related to NAD+-dependent amino acid dehydrogenases rather than characterized ornithine cyclodeaminases. Therefore, this prompted us to propose several new mechanisms of L-Dap synthesis (Figure 3, Schemes B-D), emphasizing the role of SbnB as an amino acid dehydrogenase, while SbnA would continue to serve the function of a β-replacement enzyme or aminotransferase. As illustrated in Figure 3, scheme B, SbnB acts as an NAD+-dependent L-Glu dehydrogenase that converts L-Glu to 2-oxoglutarate (or α-KG). This reaction will release an ammonia molecule to be used by SbnA in an identical manner to the second half of the reaction proposed in scheme A. The reaction depicted in scheme B is attractive since all products of this mechanism can be funneled towards staphyloferrin B biosynthesis (i.e. α-KG is a substrate for SbnC, while L-Dap is a substrate for SbnE and SbnF), as opposed to scheme A where the generation of L-Pro serves no purpose in staphyloferrin B biosynthesis. In scheme C, SbnA would act as the first enzyme in the pathway by condensing L-Ser with L-Glu to form a larger intermediate consisting of an L-Ser-L-Glu conjugate. In effect, SbnA would perform a β-replacement reaction on L-Ser by displacing the hydroxyl group on L-Ser with L-Glu. Dehydrogenase activity provided by SbnB would resolve and split the intermediate compound to give rise to L-Dap and 2-oxoglutarate. As in scheme B, all products from this reaction are used in the biosynthesis of staphyloferrin B. In scheme D, SbnB would serve as a 2-Ser dehydrogenase, converting L-Ser to 2-amino-3-oxopropanoic acid, an intermediate that would be primed for nucleophilic attack at the β-carbon by an ammonia molecule derived from the aminotransferase activity of SbnA. The source of this ammonia might be L-Glu, L-Asp, or L-Ala, which are all common amino group donors. In this scheme, if L-Glu is used as the amino donor, 2-oxoglutarate is produced and would be a substrate for the SbnC synthetase.

Unlike the substrate uncertainty exhibited by SbnB, the substrate for SbnA homologs have been defined through precursor labeling studies [37,38]. Since, an SbnA homologue is involved in L-Dap production for viomycin (Table 4), then it is very likely that L-serine (or the O-acetylated derivative) is also the substrate for SbnA. Moreover, a recent study by Zhao et al. [32] characterized the gene zwa5A, an SbnA homologue (Table 4), and through genetic knockout of this gene in Bacillus thuringiensis, confirmed that it is involved in synthesizing L-Dap for the antibiotic zwittermicin A. Similar to our experiments, these researchers were able to restore the production of zwittermicin A in the zwa5A mutant by providing exogenous L-Dap to the culture media [32].

It is important to note that β-replacement reactions involving ammonia as the nucleophile are rare. Only recently was an L-2,3-diaminobutyric acid (L-Dab) synthase studied that is involved in mureidomycin A production [39]. This enzyme, which catalyzes a similar reaction to the ones proposed for SbnA (Figure 3), will use L-Thr as the substrate (instead of L-Ser) and will displace the β-hydroxyl group with an ammonia molecule to form L-Dab. However, the source of the ammonia was not described and thus it is assumed that this enzyme may depend on cellular concentrations of free ammonia rather then receiving the ammonia from a dedicated dehydrogenase. The idea that an enzyme acquires free ammonia within a cell is intriguing. Certainly, the rate of diffusion of ammonia inside a cell can be a limiting factor and this is perhaps why both halves of an L-Dap synthase appear to be consistently co-expressed, and potentially are intimately associated with one another such that liberated ammonia by the dehydrogenase unit can be properly channeled to the aminotransferase unit. This would ensure catalytic efficiency and also assumes that extensive protein-protein interactions would occur between the two enzymes. Certainly, this idea is supported by the existence of single-polypeptide encoding genes found within the P. syringae and Acidobacterium capsulatum genome, in which half of the polypeptide shares significant similarity with SbnA and the other half shares significant similarity with SbnB (Table 4).

It is interesting that supplementation of the S. aureus culture medium with L-Dap enhanced staphyloferrin B output in wildtype cells (Figure 2B cf. 2C), a phenomenon that has previously been observed [15]. It is tempting to speculate that L-Dap may be a critical molecule in terms of regulating staphyloferrin B production or that the presence of L-Dap is a signal for the organism to commit to staphyloferrin B synthesis. At this time, how such a signal may be transduced is unknown but perhaps L-Dap can induce allosteric effects on certain Sbn proteins that may, in turn, regulate staphyloferrin B production. Interestingly, enhancement of end product formation by L-Dap feeding has also been observed for zwittermicin A production in B. thuringiensis [32].

The biochemical schemes for L-Dap synthesis, as depicted in Figure 3, await experimentation with purified enzymes as well as screening with potential substrates, and these experiments are under investigation in our laboratory. Certainly, the actual mechanism of L-Dap synthesis may not be restricted to those mechanisms outlined here, but at least these provide a starting point towards the biochemical investigation of L-Dap synthase enzymes in different bacteria. No matter the mechanism, it is most surely to be novel. Regardless, the studies here have demonstrated the essentiality of SbnA and SbnB towards L-Dap synthesis in S. aureus, a nonproteinogenic amino acid component of staphyloferrin B that is critical to the iron coordinating function of the siderophore, as well as providing implications for the role that L-Dap may play in regulating production of the molecule.

Conclusions

Mutation of either sbnA or sbnB result in abrogation of synthesis of staphyloferrin B, a siderophore that contributes to iron-restricted growth of S. aureus. The loss of staphyloferrin B synthesis is due to an inability to synthesize the unusual amino acid L-2,3-diaminopropionic acid which is an important, iron-liganding component of the siderophore structure. It is proposed that SbnA and SbnB function together as an L-Dap synthase in the S. aureus cell.

Authors' contributions

FCB and JC carried out the molecular genetic and bioinformatics studies and drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in the design of the study, and edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Federico C Beasley, Email: fred.beasley@gmail.com.

Johnson Cheung, Email: jcheun56@uwo.ca.

David E Heinrichs, Email: deh@uwo.ca.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. FCB and JC were supported by the Ontario Graduate Scholarships program. The authors would like to thank members of the Heinrichs laboratory for helpful discussions.

References

- Guerinot ML. Microbial iron transport. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:743–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman C, Delepelaire P. Bacterial iron sources: from siderophores to hemophores. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh JP, Rodriguez-Quinones F, Abdul-Tehrani H, Svistunenko DA, Poole RK, Cooper CE, Andrews SC. Global iron-dependent gene regulation in Escherichia coli. A new mechanism for iron homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(32):29478–29486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil ML, Ochsner UA. The response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to iron: genetics, biochemistry and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:399–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Garcia-Herrero A, Johanson TH, Krewulak KD, Lau CK, Peacock RS, Slavinskaya Z, Vogel HJ. Siderophore uptake in bacteria and the battle for iron with the host; a bird's eye view. Biometals. 2010;23(4):601–611. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miethke M, Marahiel MA. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71(3):413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis GL. A widely distributed bacterial pathway for siderophore biosynthesis independent of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chembiochem. 2005;6(4):601–611. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosa JH, Walsh CT. Genetics and assembly line enzymology of siderophore biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66(2):223–249. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.223-249.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley FC, Vines ED, Grigg JC, Zheng Q, Liu S, Lajoie GA, Murphy ME, Heinrichs DE. Characterization of staphyloferrin A biosynthetic and transport mutants in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72(4):947–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton JL, Tao J, Balibar CJ. Identification and characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus gene cluster coding for staphyloferrin A. Biochemistry. 2009;48(5):1025–1035. doi: 10.1021/bi801844c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konetschny-Rapp S, Jung G, Meiwes J, Zahner H. Staphyloferrin A: a structurally new siderophore from staphylococci. Eur J Biochem. 1990;191(1):65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiwes J, Fiedler H-P, Haag H, Zähner H, Konetschny-Rapp S, Jung G. Isolation and characterization of staphyloferrin A, a compound with siderophore activity from Staphylococcus hyicus DSM 20459. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;67:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt G, Denny TP. Ralstonia solanacearum iron scavenging by the siderophore staphyloferrin B is controlled by PhcA, the global virulence regulator. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(23):7896–7904. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7896-7904.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SE, Doherty-Kirby A, Lajoie G, Heinrichs DE. Role of siderophore biosynthesis in virulence of Staphylococcus aureus: identification and characterization of genes involved in production of siderophore. Infect Immun. 2004;72:29–37. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.29-37.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel H, Freund S, Nicholson G, Haag H, Jung O, Zahner H, Jung G. Purification and chemical characterization of staphyloferrin B, a hydrophilic siderophore from staphylococci. Biometals. 1993;6(3):185–192. doi: 10.1007/BF00205858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag H, Fiedler HP, Meiwes J, Drechsel H, Jung G, Zahner H. Isolation and biological characterization of staphyloferrin B, a compound with siderophore activity from staphylococci. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115(2-3):125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J, Beasley FC, Liu S, Lajoie GA, Heinrichs DE. Molecular characterization of staphyloferrin B biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74(3):594–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MG, Chan YA, Ozanick SG. Deciphering tuberactinomycin biosynthesis: isolation, sequencing, and annotation of the viomycin biosynthetic gene cluster. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(9):2823–2830. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2823-2830.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebulsky MT, Speziali CD, Shilton BH, Edgell DR, Heinrichs DE. FhuD1, a ferric hydroxamate-binding lipoprotein in Staphylococcus aureus: a case of gene duplication and lateral transfer. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(51):53152–53159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiswirth BN, Lofdahl S, Bentley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng HL, Novick RP, Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Schlievert P. Cloning, characterization, and sequencing of an accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170(9):4365–4372. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4365-4372.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie ES, Lorenz LL. Staphylococcal coagulase: mode of action and antigenicity. J Gen Microbiol. 1952;6:95–107. doi: 10.1099/00221287-6-1-2-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley FC, Marolda CL, Cheung J, Buac S, Heinrichs DE. Staphylococcus aureus Transporters Hts, Sir, and Sst Capture Iron Liberated from Human Transferrin by Staphyloferrin A, Staphyloferrin B, and Catecholamine Stress Hormones, Respectively, and Contribute to Virulence. Infect Immun. 2011;79(6):2345–2355. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00117-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérout-Fleury AM, Shazand K, Frandsen N, Stragier P. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1995;167(1-2):335–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty T, Leimeister-Wåchter M, Domann E, Hartl M, Goebel W, Nichterlein T, Notermans S. Coordinate regulation of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes requires the product of the prfA gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:568–574. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.568-574.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman BT, Donegan NP, Jarry TM, Palma M, Cheung AL. Evaluation of a tetracycline-inducible promoter in Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in vivo and its application in demonstrating the role of sigB in microcolony formation. Infect Immun. 2001;69(12):7851–7857. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7851-7857.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwyn B, Neilands JB. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg JC, Cheung J, Heinrichs DE, Murphy ME. Specificity of Staphyloferrin B recognition by the SirA receptor from Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(45):34579–34588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.172924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley FC, Heinrichs DE. Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition in the staphylococci. J Inorg Biochem. 2010;104(3):282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SE, Sebulsky MT, Heinrichs DE. Involvement of SirABC in iron-siderophore import in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:8356–8362. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8356-8362.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Luo Y, Song C, Liu Z, Chen S, Yu Z, Sun M. Identification of three Zwittermicin A biosynthesis-related genes from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain YBT-1520. Arch Microbiol. 2007;187(4):313–319. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Song C, Luo Y, Yu Z, Sun M. L-2,3-diaminopropionate: one of the building blocks for the biosynthesis of Zwittermicin A in Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain YBT-1520. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(20):3125–3131. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawlaty J, Zhang X, Fischbach MA, Clardy J. Dapdiamides, tripeptide antibiotics formed by unconventional amide ligases. J Nat Prod. 2010;73(3):441–446. doi: 10.1021/np900685z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenhorst MA, Clardy J, Walsh CT. The ATP-dependent amide ligases DdaG and DdaF assemble the fumaramoyl-dipeptide scaffold of the dapdiamide antibiotics. Biochemistry. 2009;48(43):10467–10472. doi: 10.1021/bi9013165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti AD, Thomas MG. Analysis of achromobactin biosynthesis by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(14):4594–4604. doi: 10.1128/JB.00457-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Sun F, Cho H, Yelavarthi V, Sohn C, He C, Schneewind O, Bae T. CcpA mediates proline auxotrophy and is required for Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(15):3883–3892. doi: 10.1128/JB.00237-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JH, Du Bus RH, Dyer JR, Floyd JC, Rice KC, Shaw PD. Biosynthesis of viomycin. II. Origin of beta-lysine and viomycidine. Biochemistry. 1974;13(6):1227–1233. doi: 10.1021/bi00703a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JH, Du Bus RH, Dyer JR, Floyd JC, Rice KC, Shaw PD. Biosynthesis of viomycin. I. Origin of alpha, beta-diaminopropionic acid and serine. Biochemistry. 1974;13(6):1221–1227. doi: 10.1021/bi00703a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam WH, Rychli K, Bugg TD. Identification of a novel beta-replacement reaction in the biosynthesis of 2,3-diaminobutyric acid in peptidylnucleoside mureidomycin A. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:1912–1917. doi: 10.1039/b802585a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]