Abstract

Heat shock protein 10 (Hsp10) in eukaryotes, originally identified as a mitochondrial chaperone, now is also known to be present in cytosol, cell surface, extracellular space and peripheral blood. Functionally besides participating in mitochondrial protein folding in association with Hsp60, Hsp10 appears to be related to pregnancy, cancer and autoimmune inhibition. Hsp10 can be released to peripheral blood at very early time point of pregnancy and given another name called early pregnancy factor (EPF), which seems to play a critical role in developing a pregnant niche. In malignant disorders, Hsp10 is usually abnormally expressed in the cytosol of malignant cells and further released to extracellular space, resulting in tumor-promoting effect from various aspects. Furthermore, distinct from other heat shock protein members, whose soluble form is recognized as danger signal by immune cells and triggers immune responses, Hsp10 after release, however, is designed to be an inhibitory signal by limiting immune response. This review discusses how Hsp10 participates in various physiological and pathological processes from basic protein molecule folding to pregnancy, cancer and autoimmune diseases, and emphasizes how important the location is for the function exertion of a molecule.

Keywords: Hsp10, location, pregnancy, autoimmune disease, cancer

Introduction

Heat shock proteins are among the most conserved proteins in evolution and present in cells normally but overexpressed when exposed to a stress such as sudden temperature jump. Acting as intracellular chaperones, heat shock proteins correct unfolding or misfolding proteins so to keep cell with normal function. To date, a large number of heat shock protein members have been identified, and among them, Hsp10 is a 10 kDa, highly conserved, mitochondrion-resident protein, which co-chaperones with another mitochondrial heat shock protein Hsp60 for protein folding as well as the assembly and disassembly of protein complexes. Moreover, Hsp10 alone is widely involved in protecting prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells from stresses caused by infection, inflammation and others [1–3]. Such versatile effects of Hsp10 are linked to its changeable location either in cytosol or extracellular space. Hsp10 prototypically functions as chaperone in mitochondria, however the expression of Hsp10 in cytosol [4], cell surface [5], extracellular fluid [6] and peripheral blood [7] is associated with a variety of activities in immunomodulation and cell proliferation and differentiation. It has been known that the deregulation and malfunction of heat shock proteins contribute to a large number of tissue-specific and systemic disorders, including various types of cancer and autoimmune diseases [8]. Here, we address the prototypic location and the secretion pathways of Hsp10 and the associations between Hsp10 location and pregnancy, autoimmunity as well as cancer. A better understanding of intra- and extracellular functions of Hsp10 may potentially allow us to develop new strategies to treat Hsp10 involved cancers, inflammation-related diseases, and other disorders.

Location of Hsp10

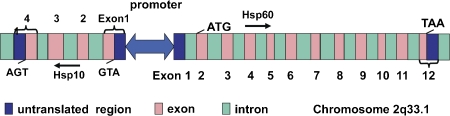

Human Hsp10 is encoded by a nuclear gene HSPE1 (GeneID: 3336) on chromosome 2q33.1. The close functional correlation existing in the mitochondrial matrix between Hsp10 and Hsp60 is reflected in the structure and localization of their genes. The human genes of both proteins (HSPE1 and HSPD1 for Hsp10 and Hsp60, respectively) are located on the same chromosome and they place head-to-head on opposite strands. As shown in Figure 1, HSPE1 and HSPD1 are controlled by a bidirectional promoter, with the two genes spanning approximately 17kb, and consisting of 4 and 12 exons respectively [9]. This locus organization lends itself to co-regulation of the two genes with simultaneous overexpression in eukaryotic cells under various conditions including carcinogenesis [2,4,10,11] and post-ischemia of brain [12]. Generally, Hsp10 is originally translated in the cytoplasm and transported into and localized in the mitochondrial matrix and chloroplasts (in plants), where it forms heterodimer with Hsp60 that exerts the function by capturing and refolding partially folded or unfolded proteins and assisting them for correct conformation [9]. Besides mitochondria, mounting evidence demonstrates that Hsp10 can also be located in cytosol, cell membrane, intercellular space, and periphery [3,13]. However, mechanisms by which Hsp10 is sequestered in the mitochondrial and released into the extracellular space have not been elucidated yet.

Figure 1.

The gene structure of HSPE1 and HSPD1.

Hsp10 does not have a N-terminal signal peptide for the secretion, suggesting that its extracellular exportation has to be proceeded through a non-classical endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi-independent pathway. Although the mechanisms of leaderless protein secretion are much incompletely understood, two main pathways have been proposed. First, some proteins such as FGF-1 and IL-1α, can translocate across the plasma membrane through the formation of multiprotein complexes as a “molten globule” form [14–16]. It has been conjectured that heat shock stimulates this pathway by allowing Hsp10 to partially unfold, as partial unfolding is required for membrane translocation of many proteins [15,17]. The second pathway by which IL-1β crosses membrane, involves entry of the secreted protein into endolysosomes and release from the cell by a vesiculation mechanism [18]. And such mechanism probably requires the activity of ATP binding cassette transporters and the likely participation of purinergic receptors [19]. In addition, some secreted nuclear proteins, such as high mobility protein b1 (HMGB1) and engrailed-2, appear to be secreted through special pathway under specialized conditions that promote secretion [20,21]. Interestingly, the secreting pathways of Hsp60 and Hsp70 have been widely studied, and these chaperones seem to be released to the extracellular space via an alternative pathway mediated by exosomes [22–25]. Based on these findings, it is reasonable to speculate that similar secreting pathway(s) is employed to Hsp10 for its extracellular secretion.

Intracellular proteins, like HMGB1, IL-1b and others, to achieve the extracellular secretion, usually accept stimulatory signal and get modification. Hence, two important questions are raised, viz: how signals trigger the process of Hsp10 secretion and whether Hsp10 undergoes modification. Posttranslational modification is a crucial step in regulating the functions of many eukaryotic proteins, including phosphorylation of serine, threonine and tyrosine, acetylation of lysine, and methylation of lysine and arginine. In addition, amino acid transition is another type of modification. For instance, arginine residue can be converted into citrulline residue by peptidylarginine deiminases through a process called citrullination or deimination during cell death and tissue inflammation. Posttranslational modification may play a critical role in the export of leaderless proteins. HMGB1 is localized in nucleus and exerts the regulation of gene expression through DNA-binding. However, under intrinsic or extrinsic stresses, the DNA-binding lysine residues of HMGB1 are acetylated, which neutralizes the positive charge and separates HMGB1 from DNA, thus leading to the nuclear export and the subsequent release into extracellular space. As a result, by functioning as a proinflammatory factor, the released HMGB1 mediates various inflammatory processes of diseases [20,21]. Therefore, here, we propose that stimulatory signal triggers the modification of specific amino acid residue(s) of Hsp10, leading to the dissociation of Hsp10 from Hsp60/Hsp10 complex and the subsequent access into intracellular vesicles such as secretary lysosomes and the final release into the extracellular environment.

Hsp10 as molecular chaperone

In living cells, most of heat shock proteins are constitutively expressed and perform essential chaperone functions, including protein folding, re-folding, assembly, translocation, and degradation through the whole life [8,26,27]. By binding with Hsp60 to form the chaperonin, Hsp10 favors mitochondrial protein folding. Hsp60 consists of two rings stacked on each other to form barrel-shaped structure with a central cavity, the folding chamber or cage [28,29], and Hsp10 however forms a heptameric lid, which binds to a double-ring toroidal structure comprising seven Hsp60 subunits per ring [30–32]. This complex accepts unfolded and misfolded proteins into its central cavity and assists them in the folding process, which does not release the substrate protein before it reaches the native state, thus preventing non-native polypeptide aggregation [26,29]. This process may be divided into three steps: (1) the unfolded substrate is bound tightly to chaperonin; (2) the substrate protein is trapped in the cavity capped by Hsp10; and (3) the substrate protein is “ejected”. Partially folded protein will rebind to the chaperonin, continuing the cycle until folding is complete [29,33,34]. Therefore, chaperonin seems to be capable of distinguishing proteins in a native conformation from those that are correctly folded. However, this molecular and structural basis is incompletely understood. A clue might be energy molecule ATP. Chaperonin favoring substrate protein folding is driven by ATP binding and hydrolysis, which controls the conformation of the chaperonin and its affinity to substrate. Proteins in mitochondrion may be derived from nucleus or encoded by mitochondrial genes. However, mitochondrial DNA is vulnerable because (1) mitochondrial DNA is in close proximity to the mitochondrial respiratory chain, the main source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) for DNA damage; and (2) DNA repair capacity in the mitochondria is less efficient than in the nucleus. Such damaged DNA may cause many erroneous protein molecules, which need the help of chaperone for the refolding, translocation and degradation. Therefore, Hsp10 as chaperone may be critical in the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis.

Function beyond protein folding: link to pregnancy

The first report of the extracellular function of Hsp10 was derived from the study of the action of early pregnancy factor (EPF) occurred in the 1970s [35]. By the rosette inhibition test, a protein factor was detected in the pregnancy serum with immunosuppressive effect [36]. This soluble protein thereafter was named as early pregnancy factor (EPF), because it appears in the maternal serum within 24h after fertilization. It was not until 1994 that EPF has been shown to be extracelluar homolog of Hsp10 [37] . It is thought that EPF is first produced in the ovary and then secreted from blastocyst. So far, EPF has been detected in diverse animal species, such as mouse [38], sheep [39], pig [40], horse [41] and cow [39,42]. In human, EPF is detectable in serum [43], amniotic fluid [44] and fetal serum [45] of pregnant women. EPF seems to play an important role during pre-implantation and implantation stages [46,47], potentially by acting as an immunosuppressive factor to assist in preventing immune response to the early embryo, which is very important since pregnancy can only occur when the embryo can evade maternal immune surveillance. Passive immunization of pregnant mice with monoclonal or purified polyclonal antibodies to EPF induced miscarriage [48]. In addition, during the first and second trimesters, EPF is characterized to enter the blood and urine of pregnant women and to be the principal immunosuppressive agent for the establishment of pregnancy [37,49]. Interestingly, it was reported that

Hsp10 is present on the surface of the mouse spermatozoa where it may aid in sperm capacitation. Thus in addition to having biological actions in the body fluids, Hsp10 may also have functions when it is located on the outer cell membrane [5]. Taken together, Hsp10 as EPF may provide us with wide clinical applications, such as testing the occurrence of fertilization in vivo, predicting the prognosis of pregnancy, and evaluating embryo quality in the in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer treatment.

The good side of Hsp10: anti-autoimmunity

The development of autoimmune diseases is a result of losing immune tolerance by the defect of immune regulatory cells or molecules. Modern chaperonology has taught us that Hsp10 play a critical role in inhibiting the inflammatory responses to a number of noxae or stressors [1,3,50]. Several studies showing that Hsp10 therapies decrease clinical signs of experimental autoimmune diseases are summarized in Table 1. In an allogeneic graft model, recombinant human Hsp10 was demonstrated to be capable of prolonging the skin graft survival time [51]. In a murine model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), it was found that recombinant Hsp10 plays a major role in the reduction of disease signs [52]. The underlying mechanism might be explained by that Hsp10 not only downregulates the expression of integrins LFA-1, VLA-4 and Mac-1 and adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in the central nervous system (CNS), but also inhibits the infiltration of effector T cells to the parenchyma of the spinal cord [53]. Moreover, Hsp10 may target TLR signaling, inhibiting lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced nuclear factor-κB activation and secretion of inflammatory mediators TNF-α, IL-6, and RANTES from either murine macrophages or human peripheral blood mononuclear cells [1,3]. In patients with periodontal disease, circulating levels of Hsp10 are lower than those in matched, disease-free controls and blood Hsp10 levels come back to normal only after effective therapy [6]. In a phase I clinical trial of multiple sclerosis, it was found that Hsp10 significantly inhibits the production of critical proinflammatory cytokines by leukocytes, and that no significant differences in the frequency of adverse events were seen between treatment and placebo arms. Hsp10 might also be useful in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Patients with moderate-to-severe active rheumatoid arthritis were received with various intravenous doses of recombinant Hsp10 (twice a week for 12 weeks) and showed much amelioration of clinical signs and well tolerance [54]. Together, these findings demonstrated that extracellular space-locating Hsp10 is possessed of a strong immunosuppressive activity, suggesting that Hsp10 might be a potential therapeutic agent in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Nonetheless, the detailed mechanism (s) and the corresponding signaling pathway(s) triggered by extracellular Hsp10 still remain elusive.

Table 1.

Hsp10 in anti-autoimmunity

| Autoimmune disease | Applied Hsp10 | Mechanism | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin graft | Recombinant | Modify Th1 responses | Prolong survival time | [51] |

| multiple sclerosis/EAE1 | Recombinant | Downregulate expression of integrins and adhesion molecules; inhibit the infiltration of effector T cells | Alleviate clinical signs | [52] |

| Periodontal disease | Endogenous after effective therapy | Inhibit intracellular signaling pathways through TLRs | Elevate the level of Hsp10 | [53] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Recombinant | Inhibit the production of a range of cytokines | Tolerate well and ameliorate the clinical signs | [54] |

Abbreviations: EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.

Pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) is the term generally referred to microbe-derived molecules, which can be recognized by a set of receptors called pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). In contrast to exogenous PAMPs, endogenous molecules capable of eliciting innate immune responses are termed damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP). Both PAMPs and DAMPs use the same PRRs for signaling transduction, typically Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [55–57]. Many endogenous molecules have been identified as DAMPs, which function as potential TLR ligands, including the degraded products of extracellular matrix components, nuclear materials, and the nuclear protein high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) as well as heat-shock proteins, such as HSP60, HSP70 and HSP90 [4,11]. By considered as danger signals, intracellular proteins may potentially act as DAMPs, once they translocate to extracellular spaces. In this respect, when released from stressed or dead cells to interstitial milieu, Hsp10 might be conferred a new identity as a DAMP molecule to trigger TLR signaling, just as its other family members do. However, the difference is that other heat shock proteins such as Hsp70 stimulate inflammatory responses through TLR signaling and Hsp10, in contrast, exerts anti-inflammatory effects. One possible explaination is that Hsp10 might occupy and saturate the binding site for other TLR ligands. Besides TLRs, Hsp10 might bind to other PRRs, such as CD14, CD36, and CD91. Moreover, the class E scavenger receptors, known as lectinlike oxidized LDL receptor-1(LOX-1) expressed in dendritic cells, are reported to participate in Hsp70 binding [58], suggesting a possibility that such receptor might also involved in the modulation of Hsp10 binding. Irrespective of the rationality of these speculations, much more experimental evidences are needed to be done to uncover the real face of Hsp10 binding and the correlated signaling pathway.

The bad side of Hsp10: tumor promotion

The relationship between heat shock proteins and tumor has been intensively studies for a long time. Certain heat shock proteins such as Hsp70, Hsp90 and Grp78 are well known for their tumor-promoting effects in a variety of human malignancies through protecting cancer cells against apoptosis in response to a variety of stresses. Nevertheless, relative to those studies, studies on Hsp10 in tumor are much lagged and how Hsp10 affects tumor is much unclear, even if some recent studies indicated the potential positive role of Hsp10 in turmorigenesis [13,59]. Consistent to Hsp70 and others, the overexpression of Hsp10 is found in several tumor and pretumoral cells [2,10,60,61] and the number of Hsp10-positive cells was significantly increased in secondary follicles and medullary sinus in metastatic lymph nodes compared to hyperplastic lymph nodes [4,13,62]. Besides the different expression levels, interestingly, Hsp10 is localized differently in normal and cancer cells. In normal cells, majority of Hsp10 is localized in the mitochondrial matrix, whereas in tumor cells Hsp10 reaches much higher levels in the cytosol [4]. Therefore, Hsp10 seems to accumulate in the cytoplasm of dysplastic and neoplastic cells and its expression is increased during the transition from dysplasia towards carcinoma. The increase of intracellular Hsp10 is a prelude for its secretion into the cellular space and subsequent modulation of the antitumor immune response, which is linked to the pathogenesis of premalignant conditions. Thus, the up-regulation of Hsp10 occurred in the early stage of carcinogenesis might be serve as an index for early diagnosis of large bowel carcinomas [4,10,60,61,63]. However, the opposite case was reported in that Hsp10 was down-regulated during bronchial and vesical carcinogenesis and the reasons behind these quantitative variations have not been elucidated [64].

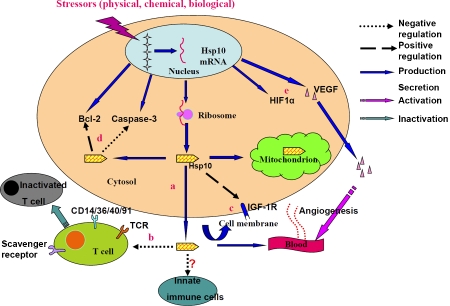

Hsp10 might employ different mechanisms to influence tumor initiation and progression [2–4,65–67]. In some model systems, evidences indicate that the tumor cells have developed mechanisms to subvert the immune system and the increased levels of Hsp10 seem to be correlated with a downregulated immune response. It has been suggested that this downregulation takes place by suppressing the expression of the signal-transducing zeta chain associated with the T-cell receptor (TCR) known as CD3-zeta, and T cells with suppressed zeta chain exhibit diminished proliferation and production of cytokines [68–70]. Several types of receptors have been described to be potentially involved in heat shock protein binding, such as TLR2/4, CD14, CD36, CD40, CD91, and scavenger receptors [71–74]. However, since the specific receptor has not been found, it is possible that Hsp10 is internalized with the engaged receptors or via non-receptor-mediated mechanisms as gp96 [75]. Irrespective of how Hsp10 suppresses T cell expressing CD3 zeta chain, the resultant inhibition of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte activation may play a critical role in the cancer progression [65]. Nevertheless, whether Hsp10 employs other mechanisms to mediate tumor immune escape remains elusive.

It has been reported that Hsp10 is selectively expressed by myeloid and megakaryocytic precursors in human bone marrow but these features disappear after lineage maturation, suggesting that Hsp10 might influence the function of signal elements and play a role in lineage differentiation and/or proliferation [76]. In line with this, it has been shown that neutralization of Hsp10 by antibody significantly decreased the uptake of thymidine by liver cells, and the peripheral blood levels of Hsp10 was strikingly increased 8 hours after partial hepatectomy [77]. This might be explained by (1) the involvement of Hsp10 signaling in DNA synthesis in an autocrine or paracrine form [78]; and (2) the promoting effect of Hsp10 on functional receptors such as IGF-1 receptor [79]. Therefore, Hsp10 might contribute to tumor cell growth. Moreover, Hsp10 might be also involved in the regulation of tumor cell apoptosis by inhibiting apoptosis and shifting the balance towards cell survival. Overexpression of Hsp10 in cancer cells inhibits tumor cell apoptosis by increasing the abundance of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 and decreasing the expression of caspase-3 [80]. Furthermore, Hsp10 appears to be able to complex with pro-caspase-3, thus inhibiting the activation of pro-caspase-3 and promoting the survival of tumor cells [81]. In addition, Hsp10 could be involved in Ras GTPase signaling pathway, thus influencing tumorigenesis [82].

Angiogenesis is required for invasive tumor growth and metastasis and constitutes an important point in the control of cancer progression. To grow beyond the diffusion distance of oxygen in tissue (100 μm), tumors must assemble additional microcirculation through de novo angiogenesis [83]. Heat shock proteins are important in such a process via their influence on the key transcription factor HIF-1a, the primary sensor of tumor hypoxia [84]. The increased amounts of both Hsp70 and Hsp90 were needed to mediate HIF-1a stabilization and accumulation [84]. To date, the promoting effect of Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp27 and Grp78 on neoangiogenesis has been well demonstrated [85–89]. In this respect, whether Hsp10 plays a role in tumor angiogenesis is worthy of study. Taken together, Hsp10 not only facilitates tumor immune evasion but also favors tumor cell growth and survival as well as probably tumor angiogenesis (Figure 2), suggesting that Hsp10-based methods and reagents have potential therapeutic values against tumor and a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of Hsp10-mediated tumor promotion should further strengthen such therapeutic efficiency.

Figure 2.

Possible mechanisms of Hsp10 in tumor promotion: a) accumulation of Hsp10 in tumor cell and then release into extracellular space; b) suppression of the signal transduction of CD3-zeta chain of TCR and inactivation of T cells, and the possible involvement of TRL2/4, CD14,CD36,CD40,CD91 and scavenger receptors in this process; c) increase of the number of functional receptors and amplifying activation of IGF-1R signaling; d) inhibition of apoptosis by increasing the abundance of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 and downregulation of capase-3; and e) enhanced angiogenesis through increasing the amount of paramount factors such as HIF-1α and VEGF.

Concluding remarks

Multi-functional exertion by Hsp10 depends on its location in mitochondrion, cytosol or extracellular space. Particularly, extracellular Hsp10, seemingly as an antagonist of other extracellular heat shock proteins, plays an important role in the inhibition of immunoinflammatory reaction. Two basic questions about such extracellular Hsp10 remain to be answered: (1) how Hsp10 is released; and (2) how the Hsp10 signal is transduced. A better understanding of the secretion mechanism and signaling pathway of Hsp10 undoubtedly benefits this protein-based application in the prevention, therapy and diagnosis of cancer and other immune-related diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation of Wuhan City Human Resource for Returned Scholars; the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-08-0219), the Funds for International Cooperation and Exchange of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30911120482), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31000640), the Important National Science & Technology Specific Projects (2009ZX09301-014).

References

- [1].Johnson BJ, Le TT, Dobbin CA, Banovic T, Howard CB, Flores Fde M, Vanags D, Naylor DJ, Hill GR, Suhrbier A. Heat shock protein 10 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory mediator production. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4037–4047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cappello F. HSP60 and HSP10 as diagnostic and prognostic tools in the management of exocervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:661. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Corrao S, Campanella C, Anzalone R, Farina F, Zummo G, Conway de Macario E, Macario AJ, Cappello F, La Rocca G. Human Hsp10 and Early Pregnancy Factor (EPF) and their relationship and involvement in cancer and immunity: current knowledge and perspectives. Life Sci. 2010;86:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cappello F, David S, Rappa F, Bucchieri F, Marasa L, Bartolotta TE, Farina F, Zummo G. The expression of HSP60 and HSP10 in large bowel carcinomas with lymph node metastase. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Walsh A, Whelan D, Bielanowicz A, Skinner B, Aitken RJ, O'Bryan MK, Nixon B. Identification of the molecular chaperone, heat shock protein 1 (chaperonin 10), in the reproductive tract and in capacitating spermatozoa in the male mouse. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:983–993. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shamaei-Tousi A, D'Aiuto F, Nibali L, Steptoe A, Coates AR, Parkar M, Donos N, Henderson B. Differential regulation of circulating levels of molecular chaperones in patients undergoing treatment for periodontal disease. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sadacharan SK, Cavanagh AC, Gupta RS. Immunoelectron microscopy provides evidence for the presence of mitochondrial heat shock 10-kDa protein (chaperonin 10) in red blood cells and a variety of secretory granules. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;116:507–517. doi: 10.1007/s00418-001-0344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Macario AJ, Conway de Macario E. Sick chaperones, cellular stress, and disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1489–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hansen JJ, Bross P, Westergaard M, Nielsen MN, Eiberg H, Borglum AD, Mogensen J, Kristiansen K, Bolund L, Gregersen N. Genomic structure of the human mitochondrial chaperonin genes: HSP60 and HSP10 are localised head to head on chromosome 2 separated by a bidirectional promoter. Hum Genet. 2003;112:71–77. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cappello F, Bellafiore M, David S, Anzalone R, Zummo G. Ten kilodalton heat shock protein (HSP10) is overexpressed during carcinogenesis of large bowel and uterine exocervix. Cancer Lett. 2003;196:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rodolico V, Tomasello G, Zerilli M, Martorana A, Pitruzzella A, Marino Gammazza A, David S, Zummo G, Damiani P, Accomando S, Conway de Macario E, Macario AJ, Cappello F. Hsp60 and Hsp10 increase in colon mucosa of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15:877–884. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0196-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kim SW, Lee JK. NO-induced downregulation of HSP10 and HSP60 expression in the postischemic brain. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1252–1259. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Czarnecka AM, Campanella C, Zummo G, Cappello F. Heat shock protein 10 and signal transduction: a “capsula eburnea” of carcinogenesis? Cell Stress Chaperones. 2006;11:287–294. doi: 10.1379/CSC-200.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Prudovsky I, Mandinova A, Soldi R, Bagala C, Graziani I, Landriscina M, Tarantini F, Duarte M, Bellum S, Doherty H, Maciag T. The non-classical export routes: FGF1 and IL-1alpha point the way. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4871–4881. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Arai M, Kuwajima K. Role of the molten globule state in protein folding. Adv Protein Chem. 2000;53:209–282. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(00)53005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fujiwara K, Arai M, Shimizu A, Ikeguchi M, Ku-wajima K, Sugai S. Folding-unfolding equilibrium and kinetics of equine betalactoglobulin: equivalence between the equilibrium molten globule state and a burst-phase folding intermediate. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4455–4463. doi: 10.1021/bi982683p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mambula SS, Calderwood SK. Heat shock protein 70 is secreted from tumor cells by a nonclassical pathway involving lysosomal endosomes. J Immunol. 2006;177:7849–7857. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Andrei C, Margiocco P, Poggi A, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Rubartelli A. Phospholipases C and A2 control lysosome-mediated IL-1 beta secretion: Implications for inflammatory processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9745–9750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308558101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Marty V, Medina C, Combe C, Parnet P, Amedee T. ATP binding cassette transporter ABC1 is required for the release of interleukin-1beta by P2X7-stimulated and lipopolysaccharideprimed mouse Schwann cells. Glia. 2005;49:511–519. doi: 10.1002/glia.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gardella S, Andrei C, Ferrera D, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Bianchi ME, Rubartelli A. The nuclear protein HMGB1 is secreted by monocytes via a non-classical, vesicle-mediated secretory pathway. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:995–1001. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Maizel A, Bensaude O, Prochiantz A, Joliot A. A short region of its homeodomain is necessary for engrailed nuclear export and secretion. Development. 1999;126:3183–3190. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gupta S, Knowlton AA. HSP60 trafficking in adult cardiac myocytes: role of the exosomal pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H3052–3056. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01355.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cappello F, Conway de Macario E, Di Felice V, Zummo G, Macario AJ. Chlamydia tra-chomatis infection and anti-Hsp60 immunity: the two sides of the coin. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000552. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Endo T, Yamano K. Multiple pathways for mitochondrial protein traffic. Biol Chem. 2009;390:723–730. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhan R, Leng X, Liu X, Wang X, Gong J, Yan L, Wang L, Wang Y, Wang X, Qian LJ. Heat shock protein 70 is secreted from endothelial cells by a non-classical pathway involving exosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;387:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Horwich AL, Fenton WA, Chapman E, Farr GW. Two families of chaperonin: physiology and mechanism. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:115–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ghosh JC, Dohi T, Kang BH, Altieri DC. Hsp60 regulation of tumor cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5188–5194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Azem A, Diamant S, Kessel M, Weiss C, Goloubinoff P. The protein-folding activity of chaperonins correlates with the symmetric GroEL14(GroES7)2 heterooligomer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:12021–12025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Coluzza I, De Simone A, Fraternali F, Fren-kel D. Multi-scale simulations provide supporting evidence for the hypothesis of intramolecular protein translocation in GroEL/GroES complexes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fiaux J, Bertelsen EB, Horwich AL, Wuthrich K. NMR analysis of a 900K GroEL GroES complex. Nature. 2002;418:207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature00860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Meyer AS, Gillespie JR, Walther D, Millet IS, Doniach S, Frydman J. Closing the folding chamber of the eukaryotic chaperonin requires the transition state of ATP hydrolysis. Cell. 2003;113:369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Xu Z, Horwich AL, Sigler PB. The crystal structure of the asymmetric GroEL-GroES-(ADP) 7 chaperonin complex. Nature. 1997;388:741–750. doi: 10.1038/41944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lin KM, Lin B, Lian IY, Mestril R, Scheffler IE, Dillmann WH. Combined and individual mitochondrial HSP60 and HSP10 expression in cardiac myocytes protects mitochondrial function and prevents apoptotic cell deaths induced by simulated ischemia-reoxygenation. Circulation. 2001;103:1787–1792. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Levy-Rimler G, Bell RE, Ben-Tal N, Azem A. Type I chaperonins: not all are created equal. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Morton H, Hegh V, Clunie GJ. Immunosuppression detected in pregnant mice by rosette inhibition test. Nature. 1974;249:459–460. doi: 10.1038/249459a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Morton H, Rolfe B, Clunie GJ. An early pregnancy factor detected in human serum by the rosette inhibition test. Lancet. 1977;1:394–397. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92605-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cavanagh AC, Morton H. The purification of early-pregnancy factor to homogeneity from human platelets and identification as chaperonin 10. Eur J Biochem. 1994;222:551–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Orozco C, Perkins T, Clarke FM. Platelet-activating factor induces the expression of early pregnancy factor activity in female mice. J Reprod Fertil. 1986;78:549–555. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0780549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nancarrow CD, Wallace AL, Grewal AS. The early pregnancy factor of sheep and cattle. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1981;30:191–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Morton H, Morton DJ, Ellendorff F. The appearance and characteristics of early pregnancy factor in the pig. J Reprod Fertil. 1983;69:437–446. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0690437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ohnuma K IK, Miyake Y-I, Tahakashi J, Ya-suda Y. Detection of early pregnancy factor (EPF) in mare sera. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 1996;42:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ghaffari Laleh V, Ghaffari Laleh R, Pirany N, Moghadaszadeh Ahrabi M. Measurement of EPF for detection of cow pregnancy using rosette inhibition test. Theriogenology. 2008;70:105–107. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Qin ZH, Zheng ZQ. Detection of early pregnancy factor in human sera. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol. 1987;13:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zheng ZQ, Qin ZH, Ma AY, Qiao CX, Wang H. Detection of early pregnancy factor-like activity in human amniotic fluid. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1990;22:9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1990.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wang HN, Zheng ZQ. Detection of early pregnancy factor in fetal sera. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1990;23:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1990.tb00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Athanasas-Platsis S, Morton H, Dunglison GF, Kaye PL. Antibodies to early pregnancy factor retard embryonic development in mice in vivo. J Reprod Fertil. 1991;92:443–451. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0920443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cheng SJ, Zheng ZQ. Early pregnancy factor in cervical mucus of pregnant women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:102–105. doi: 10.1046/j.8755-8920.2003.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Athanasas-Platsis S, Quinn KA, Wong TY, Rolfe BE, Cavanagh AC, Morton H. Passive immunization of pregnant mice against early pregnancy factor causes loss of embryonic viability. J Reprod Fertil. 1989;87:495–502. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0870495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cavanagh AC. Identification of early pregnancy factor as chaperonin 10:implications for understanding its role. Rev Reprod. 1996;1:28–32. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0010028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Macario AJ, Cappello F, Zummo G, Conway de Macario E. Chaperonopathies of senescence and the scrambling of interactions between the chaperoning and the immune systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1197:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Morton H, McKay DA, Murphy RM, Somodevilla-Torres MJ, Swanson CE, Cassady AI, Summers KM, Cavanagh AC. Production of a recombinant form of early pregnancy factor that can prolong allogeneic skin graft survival time in rats. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:603–607. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Athanasas-Platsis S, Zhang B, Hillyard NC, Cavanagh AC, Csurhes PA, Morton H, McCombe PA. Early pregnancy factor suppresses the infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages in the spinal cord of rats during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis but has no effect on apoptosis. J Neurol Sci. 2003;214:27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zhang B, Walsh MD, Nguyen KB, Hillyard NC, Cavanagh AC, McCombe PA, Morton H. Early pregnancy factor treatment suppresses the inflammatory response and adhesion molecule expression in the spinal cord of SJL/J mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and the delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to trinitrochlorobenzene in normal BALB/c mice. J Neurol Sci. 2003;212:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Vanags D, Williams B, Johnson B, Hall S, Nash P, Taylor A, Weiss J, Feeney D. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of chaperonin 10 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:855–863. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bianchi ME. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Land WG. Injury to allografts: innate immune pathways to acute and chronic rejection. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2005;16:520–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Pluddemann A, Neyen C, Gordon S. Macro-phage scavenger receptors and host-derived ligands. Methods. 2007;43:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kaul Z, Yaguchi T, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R. Quantum dot-based protein imaging and functional significance of two mitochondrial chaperones in cellular senescence and carcinogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1067:469–473. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Tetu B, Popa I, Bairati I, L'Esperance S, Bachvarova M, Plante M, Harel F, Bachvarov D. Immunohistochemical analysis of possible chemoresistance markers identified by microarrays on serous ovarian carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1002–1010. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ghobrial IM, McCormick DJ, Kaufmann SH, Leontovich AA, Loegering DA, Dai NT, Krajnik KL, Stenson MJ, Melhem MF, Novak AJ, Ansell SM, Witzig TE. Proteomic analysis of mantle -cell lymphoma by protein microarray. Blood. 2005;105:3722–3730. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Czarnecka AM, Campanella C, Zummo G, Cappello F. Mitochondrial chaperones in cancer: from molecular biology to clinical diagnostics. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:714–720. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Fan L, Fan L, Ling J, Ma X, Cui YG, Liu JY. Involvement of HSP10 during the ovarian follicular development of polycystic ovary syndrome: Study in both human ovaries and cultured mouse follicles. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:392–397. doi: 10.1080/09513590902730796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Cappello F, Di Stefano A, David S, Rappa F, Anzalone R, La Rocca G, D'Anna SE, Magno F, Donner CF, Balbi B, Zummo G. Hsp60 and Hsp10 down-regulation predicts bronchial epithelial carcinogenesis in smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cancer. 2006;107:2417–2424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Akyol S, Gercel-Taylor C, Reynolds LC, Taylor DD. HSP-10 in ovarian cancer: expression and suppression of T-cell signaling. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Athanasas-Platsis S, Somodevilla-Torres MJ, Morton H, Cavanagh AC. Investigation of the immunocompetent cells that bind early pregnancy factor and preliminary studies of the early pregnancy factor target molecule. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:361–369. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cappello F, Rappa F, David S, Anzalone R, Zummo G. Immunohistochemical evaluation of PCNA, p53, HSP60, HSP10 and MUC-2 presence and expression in prostate carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:1325–1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Rabinowich H, Suminami Y, Reichert TE, Crowley-Nowick P, Bell M, Edwards R, Whiteside TL. Expression of cytokine genes or proteins and signaling molecules in lymphocytes associated with human ovarian carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:276–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961104)68:3<276::AID-IJC2>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Reichert TE, Rabinowich H, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL. Mechanisms responsible for signaling and functional defects. J Immunother. 1998;21:295–306. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cheriyan VT, Krishna SM, Kumar A, Jayaprakash PG, Balaram P. Signaling defects and functional impairment in T-cells from cervical cancer patients. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009;24:667–673. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2009.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Vabulas RM, Braedel S, Hilf N, Singh-Jasuja H, Herter S, Ahmad-Nejad P, Kirschning CJ, Da Costa C, Rammensee HG, Wagner H, Schild H. The endoplasmic reticulum-resident heat shock protein Gp96 activates dendritic cells via the Toll-like receptor 2/4 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20847–20853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Murshid A, Gong J, Calderwood SK. Heat shock protein 90 mediates efficient antigen cross presentation through the scavenger receptor expressed by endothelial cells-I. J Immunol. 2010;185:2903–2917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Fischer N, Haug M, Kwok WW, Kalbacher H, Wernet D, Dannecker GE, Holzer U. Involvement of CD91 and scavenger receptors in Hsp70-facilitated activation of human antigenspecific CD4+ memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:986–997. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hromadnikova I, Nguyen TT, Zlacka D, Sedlackova L, Popelka S, Veigl D, Pech J, Vavrincova P, Sosna A. Expression of heat shock protein receptors on fibroblast-like synovial cells derived from rheumatoid arthritis-affected joints. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28:837–844. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Pockley AG, Fairburn B, Mirza S, Slack LK, Hop-kinson K, Muthana M. A non-receptor-mediated mechanism for internalization of molecular chaperones. Methods. 2007;43:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Cappello F, Tripodo C, Farina F, Franco V, Zummo G. HSP10 selective preference for myeloid and megakaryocytic precursors in normal human bone marrow. Eur J Histochem. 2004;48:261–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Quinn KA, Cavanagh AC, Hillyard NC, McKay DA, Morton H. Early pregnancy factor in liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats: relationship with chaperonin 10. Hepatology. 1994;20:1294–1302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Quinn KA, Morton H. Effect of monoclonal antibodies to early pregnancy factor (EPF) on the in vivo growth of transplantable murine tumours. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1992;34:265–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01741795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Shan YX, Yang TL, Mestril R, Wang PH. Hsp10 and Hsp60 suppress ubiquitination of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and augment insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling in cardiac muscle: implications on decreased myocardial protection in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45492–45498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Shan YX, Liu TJ, Su HF, Samsamshariat A, Mes-tril R, Wang PH. Hsp10 and Hsp60 modulate Bcl-2 family and mitochondria apoptosis signaling induced by doxorubicin in cardiac muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1135–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Samali A, Cai J, Zhivotovsky B, Jones DP, Orrenius S. Presence of a pre-apoptotic complex of pro-caspase-3, Hsp60 and Hsp10 in the mitochondrial fraction of jurkat cells. Embo J. 1999;18:2040–2048. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Lin KM, Hollander JM, Kao VY, Lin B, Macpher-son L, Dillmann WH. Myocyte protection by 10 kD heat shock protein (Hsp10) involves the mobile loop and attenuation of the Ras GTP-ase pathway. Faseb J. 2004;18:1004–1006. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0348fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:15–18. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Zhou J, Schmid T, Frank R, Brune B. PI3K/Akt is required for heat shock proteins to protect hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha from pVHL-independent degradation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13506–13513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Dong D, Ni M, Li J, Xiong S, Ye W, Virrey JJ, Mao C, Ye R, Wang M, Pen L, Dubeau L, Groshen S, Hofman FM, Lee AS. Critical role of the stress chaperone GRP78/BiP in tumor proliferation, survival, and tumor angiogenesis in transgene-induced mammary tumor development. Cancer Res. 2008;68:498–505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Liu B, Ye D, Song X, Zhao X, Yi L, Song J, Zhang Z, Zhao Q. A novel therapeutic fusion protein vaccine by two different families of heat shock proteins linked with HPV16 E7 generates potent antitumor immunity and antiangiogenesis. Vaccine. 2008;26:1387–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Okawa Y, Hideshima T, Steed P, Vallet S, Hall S, Huang K, Rice J, Barabasz A, Foley B, Ikeda H, Raje N, Kiziltepe T, Yasui H, Enatsu S, Anderson KC. SNX-2112, a selective Hsp90 inhibitor, potently inhibits tumor cell growth, angiogenesis, and osteoclastogenesis in multiple myeloma and other hematologic tumors by abrogating signaling via Akt and ERK. Blood. 2009;113:846–855. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Sun J, Liao JK. Induction of angiogenesis by heat shock protein 90 mediated by protein kinase Akt and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2238–2244. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000147894.22300.4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Zhao HY, Ooyama A, Yamamoto M, Ikeda R, Haraguchi M, Tabata S, Furukawa T, Che XF, Zhang S, Oka T, Fukushima M, Nakagawa M, Ono M, Kuwano M, Akiyama S. Molecular basis for the induction of an angiogenesis inhibitor, thrombospondin-1, by 5-fluorouracil. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7035–7041. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]