INTRODUCTION

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a hereditary condition transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, which is characterized by the appearance of numerous adenomatous polyps in the colon. This condition results from mutation of the APC gene and accounts for 1% of cases of colorectal cancer.1

FAP is frequently associated with extracolonic manifestations: desmoid tumors, osteomas, pigmented lesions of the retina, adenomas of the upper gastrointestinal tract, and epidermoid cysts, as well as gastric, thyroid, suprarenal, and central nervous system cancer.2

The desmoid tumor (DT) is a benign neoplasm that occurs in 10%–20% of the patients with FAP. It originates from fascial or muscle-aponeurotic structures that foster fibroblast proliferation. DTs occur more frequently in the intra-abdominal region or the abdominal wall, although they can also be detected in extra-abdominal areas. It is a rare type of tumor, representing 0.03% of neoplasms. Compared with the general population, a patient with FAP is at an 852-fold increased risk of developing a DT.3

Although benign from a histological viewpoint, a DT can display aggressive biological behavior characterized by infiltrative growth and a high recurrence rate after resection. DTs represent the second most common cause of death in patients with FAP.

CASE REPORT

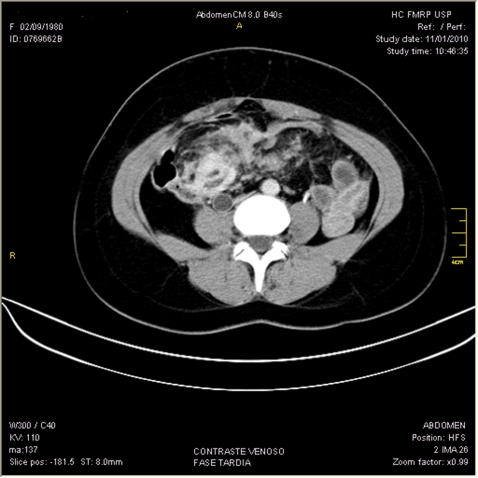

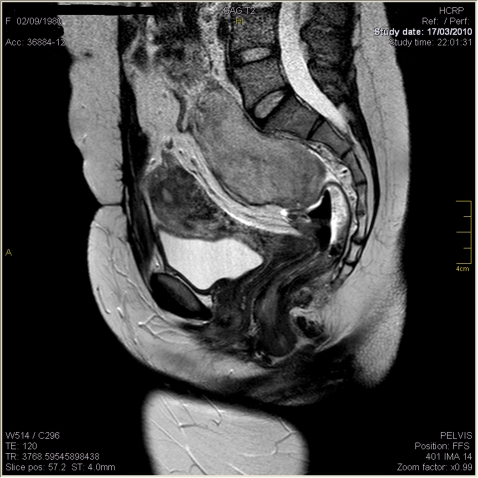

This is a report on a female patient, aged 29 years, who presented with hematochezia for one year and had a family history of FAP (mother with FAP, submitted to surgery). Colonoscopy revealed numerous polyps measuring between 0.2 and 2 cm along the colon and rectum, which confirmed FAP. The patient underwent total proctocolectomy and terminal ileostomy because of the presence of neoplastic tissue (T2N1M0) in the rectum. She received adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin. A year later, she was subjected to reconstruction of the intestinal tract with a J-shaped ileal reservoir and protective ileostomy loop. Subsequently, she was diagnosed with thyroid papillary carcinoma and was submitted to total thyroidectomy and iodine therapy. Upon clinical examination, abdominal palpation revealed a hard mass in the mesogastrium. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging examinations revealed two masses, one in the mesogastrium (8.5×5.8×3 cm) (Figure 1) and the other in the region anterior to the sacrum (6.5×5.4 cm) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography showing a huge mass in the mesogastrium. - Computed tomography showing a huge mass in the mesogastrium.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing another mass in the region anterior to the sacrum.- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing another mass in the region anterior to the sacrum.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy, which detected a large solid mass involving the mesentery and omentum, with peritoneal infiltration, which did not allow for total excision. The patient progressed satisfactorily, and the anatomopathological findings confirmed a DT. Chemotherapy with doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 was performed every 21 days for six months. The patient's progress on chemotherapy was assessed by abdominal computerized tomography. There abdominal mass displayed no progression and remained clinically stable at the 12-month follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Colorectal cancer and DTs are the main causes of death among patients with FAP. The association of DTs and FAP occurs in patients with Gardner's Syndrome. DTs and FAP have been described in 3.5% to 5.7% of the patients with this syndrome, although they can also occur in the absence of the syndrome.4,5 The association of FAP, thyroid papillary carcinoma, and a DT found in the present case is a clinical variation of Gardner's syndrome.

In some cases, DT diagnosis may precede FAP diagnosis, because the DT may develop in abdominal incisions performed for other purposes, such as appendectomy.6,7

Although composed of benign fibromatous lesions, DTs display aggressive behavior. They consist of encapsulated, slow-growing, locally aggressive tumors with infiltrative growth in adjacent tissues. The outcome is unpredictable. In some circumstances, they remit spontaneously, whereas in most cases, they grow implacably, culminating in death. Seventy percent of all DTs are intra-abdominal, but the mesentery is frequently involved as well.8 DTs also occur in the retroperitoneum, abdominal wall (incisions), inguinal region, and gluteus. Sometimes, they are multifocal.

The presence of a palpable mass in patients with FAP should lead physicians to suspect a DT. Small DTs may be asymptomatic. Symptoms are generally related to adjacent organ compression, as well as urethral obstruction, intestinal obstruction, bowel ischemia and perforation, or even aortic rupture.8,9 The 10-year survival of patients with intra-abdominal tumors can be as high as 60% to 70%; death occurs six years after diagnosis, on average.10,11

The occurrence of DTs is associated with different risk factors, such as female reproductive age, use of oral contraceptives (OCC), and pregnancy. The larger prevalence of DTs in these cases, as well as their rare occurrence before menarche and after menopause, is related to the influence of female sex hormones on tissues. Estrogen receptor counts in neoplastic tissues from women with DTs are significantly higher than those in normal tissues. Evidence that the in vitro proliferation of desmoid cells is inhibited by antiestrogen drugs suggests a strong relationship between estrogen levels and DT development.12-14 Other risk factors for DTs include previous surgery and a family history of DTs. The mechanism through which surgical trauma predisposes individuals to DTs remains unclear, but approximately 80% of patients with this tumor have already undergone previous abdominal surgeries. Patients with FAP have a 16% cumulative risk of developing DT in the ten years subsequent to colectomy, and this tumor usually appears between one and three years following colorectal surgery. The manifestation of this tumor does not seem to be associated with a specific surgery type because it is equally incident in patients that have been submitted to proctocolectomy with ileal pouch, ileal-rectum, or ileal-sigmoid anastomosis and in individuals subjected to partial colectomy.12,10,15 Patients with FAP and a family history of DTs are at a 25% increased risk of developing DTs.15

Surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are some of the approaches used to treat DTs. The treatment of choice is total resection with a safety margin. DT recurrence rates after resection lie between 60% and 85%. Less invasive surgeries are associated with fewer postoperative complications and lower recurrence rates, whereas more invasive surgeries are correlated with higher morbidity. Therefore, bypass procedures are usually preferred over resection for the correction of obstructions.8,9,15

Because of the possibility of recurrence and prolonged survival, some authors recommend that DT patients with mild symptoms should be kept under supervision only.

The use of noncytotoxic drugs, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (sulindac, indomethacin) and antiestrogen agents (tamoxifen, progesterone), has proven to be beneficial for DT patients, with reduction in tumor size and symptomatology compared with nontreated patients. The objective response rate for each of these agents is 50%. Seventy-nine percent of DTs present specific receptors for antiestrogen drugs. Some authors have suggested that intra-abdominal DT should be treated with 150 mg of sulindac twice a day. If the tumor continues to grow, tamoxifen can be administered at 80 mg/day.16-19

Cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs employed in the treatment of sarcoma (e.g., doxorubicin and carboplatin) are restricted to symptomatic patients with unresectable and clinically aggressive tumors or with tumors that do not respond to other therapies,15,20,21 as reported in this case.

The role of radiotherapy in the treatment of DTs involving the abdominal wall, either as adjuvant therapy or primary treatment, is advancing. Higher local control rates have been achieved by employing surgery associated with radiotherapy, as compared with surgery alone, especially when tumor resection is incomplete. As for intra-abdominal tumors, the use of radiotherapy is still limited because of potential complications, such as actinic enteritis.22

FAP does not occur only in the colon; indeed, the incidence of extracolonic manifestations can be as high as 40%. Hence, research, prevention, and the treatment of FAP manifestations are important. In this context, the identification of patients at risk of developing DTs is crucial for the design of prevention strategies. Moreover, it is mandatory that patients are aware of the need for periodic evaluations and that they are warned about the risk of extracolonic manifestations and their impact on the quality of life.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silva ARBM, Parra RS, Rolo JG, Filho RB, Féres O, Rocha JJR. Familiar adenomatosis polyposis: analysis of forty-four cases from the school of medicine of Ribeirão Preto Hospital and Clinics. 2007 Rev bras. Colo-proctol. vol.27, no. 3, Rio de Janeiro July/Sept. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos FG, Habr-Gama A, Kiss DR, Atuí FC, Katayama F, Gama-Rodrigues J. Extracolonic manifestations of familial adenomatous polyposis: incidence and impact on the disease outcome. Arq Gastroenterol. 2003;40:92–8. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032003000200006. 10.1590/S0004-28032003000200006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belchetz LA, Berk T, Bapat BV, Cohen Z, Gallinger S. Changing causes of mortality in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:384. doi: 10.1007/BF02054051. 10.1007/BF02054051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bussey HJR. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1975. Familial polyposis coli. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forte MD, Brant WE. Spontaneous isolated mesenteric fibromatosis: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:315. doi: 10.1007/BF02554369. 10.1007/BF02554369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corman ML. Polypoid diseases. Colon & Rectal Surgery 5th ed. 2005:p747–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAdam WA, Goligher JC. The occurrence of desmoids in patients with familial polyposis. Br J Surg. 1970;57:618–31. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800570816. 10.1002/bjs.1800570816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lotfi AM, Dozois RR, Gordon H, Hruska LS, Weiland LH, Carryer PW, Hurt RD. Mesenteric fibromatosis complicating familial adenomatous polyposis: predisposing factors and results of treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:30–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01648547. 10.1007/BF01648547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulaylat MN, Karakousis CP, Keaney CM, McCorvey D, Bem J, Ambrus JL., Sr Desmoid tumour: A pleomorfic lesion. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25:487–97. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0684. 10.1053/ejso.1999.0684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurbuz AK, Giardiello FM, Petersen GM, Krush AJ, Offerhaus GJA, Booker SV, et al. Desmoid tumors in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 1994;35:377–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.377. 10.1136/gut.35.3.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AJ, Lewis JJ, Merchant NB, Leung DH, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Surgical Management of intra- abdominal desmoid tumours. Br J Surg. 2000;87:608–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01400.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertario L, Russo A, Sala P, Eboli M, Giarola M, D'amico F. Hereditary Colorectal Tumours Registry. Genotype and phenotype factors as determinants of desmoid tumors in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. . Int J Cancer. 2001;95:102–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010320)95:2<102::aid-ijc1018>3.0.co;2-8. 10.1002/1097-0215(20010320)95:2<102::AID-IJC1018>3.0.CO;2-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim CL, Walker MJ, Mehta RR, Das Gupta TK. Estrogen and antiestrogen binding sites in desmoid tumors. Europ J Cancer clin Oncol. 1986;22:583–7. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(86)90047-7. 10.1016/0277-5379(86)90047-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tonelli F, Valanzano R, Brandi ML. Pharmacologic treatment of desmoid tumors in familial adenomatous polyposis: results of an in vitro study. Surgery. 1994;115:473–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penna C, Tiret E, Parc R, Sfairi A, Kartheuser A, Hannoun L, et al. Operation and abdominal desmoid tumors in familial adenomatous polyposis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Church JM. Desmoid tumors in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Semin Colon Rectal Surgery. 1995;6:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Côrtes BJW, Leite SMO, Campos MHR, Oliveira LA. Tumor desmóide tratado com tamoxifeno: relato de caso. 2006 Rev bras. Colo-proctol., vol.26, no. 1, Rio de Janeiro, Jan./Mar. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein WA, Miller HH, Thomas CT, Turrisi AT. The use of indomethacin, sulindac, and tamoxifen for the treatment of desmoid tumors associated with familial polyposi. Cancer. 1987;60:2863–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19871215)60:12<2863::aid-cncr2820601202>3.0.co;2-i. 10.1002/1097-0142(19871215)60:12<2863::AID-CNCR2820601202>3.0.CO;2-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsukada K, Church JM, Jagelman DG, Fazio VW, McGannon E, George CR, et al. Noncytotoxic drug therapy for intra-abdominal desmoid tumor in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:29–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02053335. 10.1007/BF02053335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwama T, Mishima Y, Utsunomiya J. The impact of familial adenomatous polyposis on the tumorigenesis and mortality at the several organs. Its rational treatment. Ann Surg. 1993;217:101–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199302000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch HT, Fitzgibbons R, Chong S, Cavalieri J, Lynch J, Wallace F, et al. Use de doxorubicin and dacarbazine for the manegemnet of iresectable intra-abdominal desmoid tumors in Gardner's syndrome: Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:260–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02048164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuyttens JJ, Rust PF, Thomas CR, Jr, Turrisi AT., 3rd Surgery versus radiation therapy for patients with agressive fibromatosis or desmoid tumors: A comparative review of 22 articles. Cancer. 2000;88:1517–23. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000401)88:7<1517::AID-CNCR3>3.0.CO;2-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]