Abstract

Background

Treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections with antimicrobial agents is controversial due to an association with potentially fatal sequelae. The production of Shiga toxins is believed to be central to the pathogenesis of this organism. Therefore, decreasing the expression of these toxins prior to bacterial eradication may provide a safer course of therapy.

Methods

The utility of decreasing Shiga toxin gene expression in E. coli O157:H7 with rifampicin prior to bacterial eradication with gentamicin was evaluated in vitro using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Toxin release from treated bacterial cells was assayed for with reverse passive latex agglutination. The effect of this treatment on the survival of E. coli O157:H7-infected BALB/c mice was also monitored.

Results

Transcription of Shiga toxin-encoding genes was considerably decreased as an effect of treating E. coli O157:H7 in vitro with the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of rifampicin followed by the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of gentamicin (> 99% decrease) compared to treatment with gentamicin alone (50-75% decrease). The release of Shiga toxins from E. coli O157:H7 incubated with the MIC of rifampicin followed by addition of the MBC of gentamicin was decreased as well. On the other hand, the highest survival rate in BALB/c mice infected with E. coli O157:H7 was observed in those treated with the in vivo MIC equivalent dose of rifampicin followed by the in vivo MBC equivalent dose of gentamicin compared to mice treated with gentamicin or rifampicin alone.

Conclusions

The use of non-lethal expression-inhibitory doses of antimicrobial agents prior to bactericidal ones in treating E. coli O157:H7 infection is effective and may be potentially useful in human infections with this agent in addition to other Shiga toxin producing E. coli strains.

Keywords: Escherichia coli O157:H7, rifampicin, gentamicin, Shiga toxins

Background

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is the most commonly encountered member of the Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) group. Infection with this agent typically results in bloody diarrhea with low-grade or absence of fever with no leukocytes in the stools [1]. Symptoms may progress, culminating in potentially fatal complications such as the hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) [2-4] and thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP) in the elderly and the young [3]. This organism causes about 73,000 illnesses annually in the United States [5].

Until recently, the most common mode of E. coli O157:H7 infection was via the oral route by consumption of ground beef. In recent years, E. coli O157:H7 has been isolated with increasing frequency from fresh produce. Other modes of infection include consumption of animal products, person-to-person transmission, waterborne, animal contact and less commonly, laboratory-associated transmission [6]. Several virulence factors contribute to the pathogenicty of E. coli O157:H7 with the production of Shiga toxins (Stxs) being at the epicenter of the infectious process. These toxins consist of two major groups: Stx1, which is nearly identical to the toxin of Shigella dysenteriae type 1, and Stx2, which shares less than 55% amino acid sequence with Stx1 [7-9]. Another virulence factor is the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) which contains genes required for the production of the attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions that accompany E. coli O157: H7 infection [10]. These genes basically allow the bacteria to colonize the intestines. The Shiga toxins have also been implicated in contributing to the process of intestinal colonization [11].

Treating E. coli O157:H7 infection with antimicrobial agents is currently contraindicated due to its association with HUS and an increased case-fatality rate [12-14]. This may be due to the activation of a stress response signal upon treatment with the antimicrobial agent that potentially leads to enhanced production and subsequent release of Shiga toxins [15]. Alternatively, the antimicrobial agent may lead to bacterial lysis and subsequent release of stored toxins that are present in the periplasmic space [16].

A potential method of treatment may involve administration of an antimicrobial agent at non-bactericidal doses that limit toxin expression prior to employing an agent at bactericidal doses. This would decrease toxin production prior to bacterial cell lysis and hence may circumvent the sequelae associated with this type of infection. We have previously demonstrated that minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of rifampicin effectively decreased toxin release from E. coli O157:H7 in vitro [17,18]. We have also shown that this agent improves the survival rate of mice infected with E. coli O157:H7 [19]. Employment of rifampicin in monotherapy is associated with evolution of rapid resistance [20]. Hence, we investigated the utility treating infected mice with rifampicin at doses that limit toxin expression followed by gentamicin at bactericidal doses to eradicate the bacterial agent.

Methods

In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of rifampicin and gentamicin for the CDC 26-98 strain E. coli O157:H7 were determined as previously described [19].

Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for assessing toxin gene transcription

To assess the effect of treating E. coli O157:H7 cells with rifampicin and gentamicin on toxin gene expression multiple regimens were tested. An inoculum of 106 CFU of the CDC 26-98 strain of E. coli O157:H7 in 2 ml of Mueller Hinton broth was incubated in the MIC of rifampicin for 18 hrs at 37°C. A similar inoculum was incubated in the MBC of gentamicin for 18 hrs at 37°C. A different sample was incubated in the MIC of rifampicin for 18 hrs at 37°C, cells were then centrifuged (5000 rpm, 5 min), and resuspended in the MBC of gentamicin prior to incubation for 4 hrs at 37°C. Similarly a sample was incubated in the MIC of rifampicin for 18 hrs at 37°C. Cells were then centrifuged and resuspended in the MBC of rifampicin prior to further incubation for 4 hrs at 37°C. An inoculum of E. coli O157:H7 grown in 2 ml of antimicrobial agent-free broth for 22 hrs at 37°C was also included as a normal growth control. None of the samples incubated with the antimicrobial agents showed any growth.

After incubations, total RNA was extracted from 106 CFU of each of the samples described above using the Illustra RNAspin Mini RNA Isolation Kit (General Electric Company, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's specifications for bacterial cells. Reverse transcription and cDNA synthesis was then performed on all samples of extracted RNA using the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Gene expression was then assessed with real-time PCR for the stx1 and stx2 genes, that respectively encode Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1) and Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2). This was performed using a BioRad CFX96 Real Time System, C1000 Thermal Cycler (Germany). Primers were obtained from Thermo Scientific (Ulm, Germany). Previously published primers were used for detection of stx1 and stx2 transcripts [21]. Reactions (20 μl), performed in triplicates per sample, each contained 738 ng cDNA, 10 pmoles of each primer and 1 × QuantiFast SYBR green PCR mix (Qiagen, germany). Reactions were incubated at 95°C for 15 minutes followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds, 55°C for 10 seconds and 72°C for 20 seconds.

Relative expression (RE) was calculated using the formula: RE = (1+ % E) ΔCt, where E is the efficiency of the real-time run and ΔCt is the difference between the Ct value of samples extracted from E. coli O157: H7 grown in the absence of drugs and the Ct value of the antimicrobial agent-treated samples. In our experiments, we used an efficiency value of 100%, therefore, the equation employed for the analysis was: RE = (1 + 1) ΔCt = (2) ΔCt. Expression levels were normalized to those detected in bacterial samples incubated with drug-free media.

Reverse passive latex agglutination (RPLA) for assessing toxin release

VTEC-RPLA "SEIKEN" kit (Denka Seiken, LTD., Tokyo, Japan) was used to assess Stx1 and Stx2 release from the CDC 26-98 strain of E. coli O157:H7 incubated in the presence of the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of gentamicin. E. coli O157:H7 was grown for 18 hrs at 37°C in rifampcin-containing TSB followed by additional 4 hrs of incubation with the MBC of gentamicin. Toxin titers were then determined by reverse passive latex agglutination (RPLA) and compared to E. coli O157:H7 grown in antimicrobial free TSB. When toxin titers were tested in bacterial cultures grown in the MIC or MBC of rifampicin, growth inhibition was accounted for and CFU numbers were adjusted to be equivalent to those grown in antimicrobial agent-free media.

Antimicrobial treatment of E. coli O157:H7-infected BALB/c mice

Adult male BALB/c mice, 4-6 weeks old and weighing 22-39 g each, were obtained from the Animal Care Facility at the American University of Beirut (AUB). The LD50 of the CDC 26-98 strain of E. coli O157:H7 in these mice was determined as previously described [19]. To assess the utility of an antimicrobial regimen for the treatment of infected mice, seven groups each containing 8 mice were used (Table 1). Mice received 3 × LD50 of the CDC 26-98 strain of E. coli O157:H7 and then were treated with the in vivo MIC equivalent dose of of rifampicin (15.168 μg), the in vivo MBC equivalent dose of gentamicin (7.584 μg) or with both successively. A group that was treated with the in vivo MIC equivalent dose of rifampicin followed by the MBC equivalent dose of the same agent was also assessed. Groups of mice that were not infected but injected with sterile broth or with the antimicrobial agents in addition to a group that was infected but not treated were included as controls. All injections were administered intraperitoneally and their volumes did not exceed 0.5 ml/mouse/day. Mice were then monitored for death and weight change over a period of 14 days. Mice were to be euthanized had they lost more than 30% of their body weight post-infection; however, this did not occur during the 14 day monitoring period.

Table 1.

Mouse treatment regimen

| Group | First Injection (Hour 0) |

Second Injection (Hour 1) |

Third Injection (Hour 17) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | E. coli O157:H7 (3 × LD50) | Rifampicin (MIC) | - |

| 2 | E. coli O157:H7 (3 × LD50) | Gentamicin (MBC) | - |

| 3 | E. coli O157:H7 (3 × LD50) | Rifampicin (MIC) | Gentamicin (MBC) |

| 4 | E. coli O157:H7 (3 × LD50) | Rifampicin (MIC) | Rifampicin (MBC) |

| 5 | Trypticase soy broth | Trypticase soy broth | Trypticase soy broth |

| 6 | Trypticase soy broth | Rifampicin (MIC) | Gentamicin (MBC) |

| 7 | E. coli O157:H7 (3 × LD50) | - | - |

The therapeutically relevant in vivo MIC equivalent dose of rifampicin was extrapolated from its in vitro MIC according to the following formula: rifampicin in vivo MIC dose (μg) = [rifampicin in vitro MIC (μg/μl) × in vitro MIC broth volume (μl) × E. coli O157:H7 CFU administered in vivo]/E. coli O157:H7 CFU per in vitro MIC reaction. Consequently, the ratio of rifampicin to E. coli O157:H7 CFU determined by in vitro MIC testing was maintained in vivo. Similarly, the therapeutically relevant in vivo MBC equivalent dose of rifampicin was extrapolated from its in vitro MBC according to the following formula: rifampicin in vivo MBC dose (μg) = [rifampicin in vitro MBC (μg/μl) × in vitro MBC broth volume (μl) × E. coli O157:H7 CFU administered in vivo]/E. coli O157:H7 CFU per in vitro MBC reaction. The same formula was used to determine the in vivo MBC equivalent dose of gentamicin.

Results

Effect of in vitro treatment with antimicrobial agents on toxin expression in E. coli O157:H7

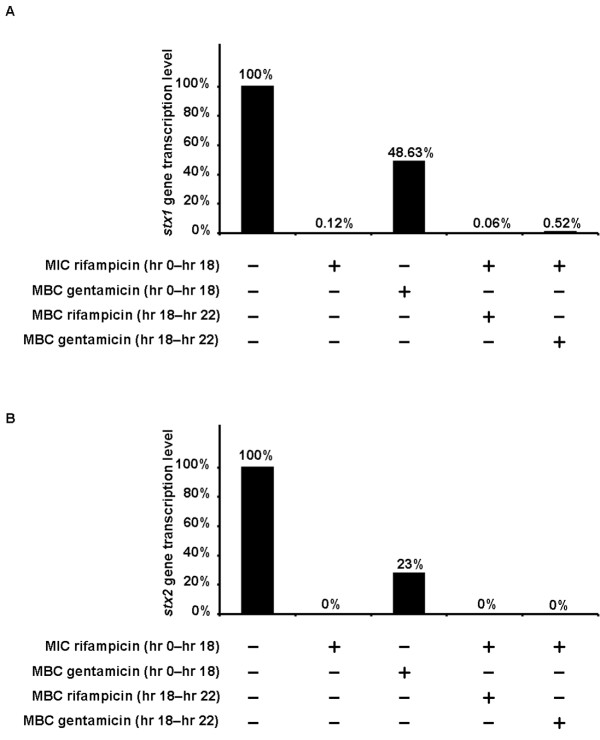

Multiple rifampicin and gentamicin treatment regimens were used to assess the effect of these agents on the expression of Stx1 and Stx2 encoding genes, stx1 and stx2, in E. coli O157:H7. Treatments tested are described in the materials and methods section. Real-time RT-PCR showed that the stx1 and stx2 genes were expressed in the E. coli O157:H7 strain employed when incubated in antimicrobial agent-free broth (Figure 1). After incubation with antimicrobial agents, levels of stx1 gene expression markedly decreased (> 99% decrease) in the sample treated with the MIC of rifampicin (8 μg/ml). A similar decrease was observed in the sample treated with the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of rifampicin (16 μg/ml) and in the sample treated with the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of gentamicin (4 μg/ml). The least inhibition of toxin gene expression (51.37% decrease) was seen in the sample treated with the MBC of gentamicin. A marked decrease in stx2 transcript detection was observed in the sample treated with the MBC of gentamcin (77% decrease.) On the other hand, stx2 expression was completely inhibited by treatment with the MIC of rifmapicin, treatment with the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of rifampicin, and treatment with the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of gentamicin.

Figure 1.

Relative transcription levels of the stx1 and stx2 genes in E. coli O157:H7 treated with antimicrobial agents. Bacterial inocula were either grown in antimicrobial-agent free broth, treated with the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of rifampicin or with the minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) of gentamicin. One sample was treated with the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of rifampicin itself while another was treated with the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of gentamicin. RNA was then extracted from these samples. Subsequently, the relative transcription levels of the stx1 and stx2 genes were assessed with real-time RT-PCR as described in the materials and methods section. All expression levels were normalized to those detected in bacteria grown in antimicrobial agent-free broth. (A) Relative transcription levels of the stx1 gene. (B) Relative transcription levels of the stx2 gene.

Treatment of E. coli O157:H7 with the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of gentamicin showed an 8-fold decrease of Stx1 toxin release into the growth medium. On the other hand, there was no change in the level of Stx2 released into the growth medium as compared to toxin titers of E. coli O157:H7 grown in antimicrobial free broth (data not shown.)

Effect of antimicobial treatment on E. coli O157:H7-infected mice

We have previously shown that treatment with the MIC of rifamipicin was capable of significantly decreasing the expression and release of both Stx1 and Stx2 from E. coli O157:H7 [17-19]. This may be employed in a treatment regimen whereby toxin production is limited prior to administering an antimicrobial agent that can effectively kill the bacteria. Therefore, we assessed this treatment approach in vivo.

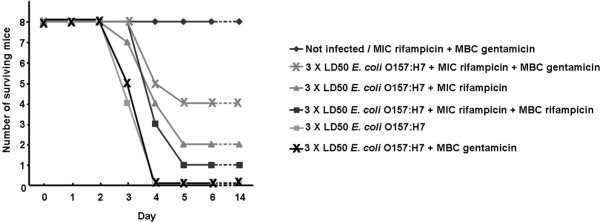

Mice were infected with 3 × LD50 of E. coli O157:H7 (equivalent to 9.48 × 105 CFU) and treated with various regimens of rifampicin and gentamicin as summarized in Table 1 and described in the materials and methods section. All mice infected with E. coli O157:H7 and left untreated or treated with the in vivo MBC equivalent dose of gentamicin were dead by day 4 post infection (Figure 2). Mice in other groups that survived until day 5 remained alive for the rest of the 14 day monitoring period. The highest survival rate was obtained with the group treated with the in vivo MIC equivalent dose of rifampicin followed by the in vivo MBC equivalent dose of gentamicin. In this group, 50% of the mice infected and treated were alive on day 5 and remained so forward. In comparison, 25% of the mice infected and treated with the in vivo MIC equivalent dose of rifampicin were alive on day 5. On the other hand, mice treated post-infection with the in vivo MIC equivalent dose of rifampicin followed by the in vivo MBC equivalent dose of rifampicin showed a 12.5% survival rate.

Figure 2.

Number of surviving BALB/c mice after infection with E. coli O157:H7 and treatment with antimicrobial agents. Male BALB/c mice were infected with E. coli O157:H7 and then treated with rifampicin and/or gentamicin as delineated in the materials and methods section. Mice were then monitored for 14 days.

Discussion

Using antimicrobial agents to treat E. coli O157:H7 infections has been contraindicated due to studies showing an association between antimicrobial treatment and increased fatality rates [4]. The quest for other treatments has led to the development of antibodies, among other agents, aimed at direct inhibition of the toxins secreted by E. coli O157:H7 and associated with the severe sequelae of infection [22,23]. While these approaches appear to be effective, their affordability limits their use. On the other hand, the use of probiotics, physical means in addition to natural and chemical products for the treatment and prevention of E. coli O157:H7 has been assessed by multiple groups with variable success [24-28].

Antimicrobial agents remain to be the method of choice for early empirical treatment of bacterial infections, particularly in the treatment of gastroenteritis in pediatric patients [26]. Antimicrobial treatment for E. coli O157:H7 may be possible if Shiga toxin expression can first be decreased before administering bactericidal doses of an agent, thus limiting potential toxin release upon lysis of the organism. This was previously established by our group in vitro [17,18] and by the study at hand in vivo.

Upon establishing that in vitro treatment of E. coli O157:H7 inocula with the MIC of rifampicin followed by the MBC of gentamicin potently decreases the transcription of the Stx1 and Stx2 encoding genes, we assessed the effect of this treatment mode on toxin release. Testing the levels of toxins released into the growth medium showed an 8-fold decrease in Stx2 levels whereas no such decrease was observed for Stx1 levels. This may be explained by the biology of production and storage of these toxins and their turnover rates. Stx1 is stored in the periplasmic space; consequently, upon addition of gentamicin at a bactericidal concentration, cells possibly ruptured and released the pre-stored Stx1. On the other hand, Stx2 is typically found in the extracellular fraction and is released from bacterial cells [29].

Treatment of infected mice with the in vivo MIC equivalent dose of rifampicin, followed by the in vivo MBC equivalent dose of gentamicin increased the survival rate of infected mice by 50%. On the other hand treatment with MBC equivalent dose of gentamicin led to the death of all mice that received this agent. Rifampicin, being a known inhibitor of gene transcription, is assumed here to have hindered the expression of the toxins by E. coli O157:H7. After suppression of toxin expression with rifampicin, treatment with gentamicin helped eradicate the infection and enhance mouse survival.

In a previous report [18], a higher fold-decrease in toxin-release was seen in vitro when E. coli O157:H7 was incubated with rifampicin or gentamicin alone compared to the decrease observed in the present study upon combinatorial treatment. However, treatment of infected mice with rifampicin followed by gentamicin proved to be more effective than when these antimicrobial agents were used individually. Therefore, in vivo, these antimicrobial agents may have had other effects additional to affecting toxin expression and release. These agents, for example, may have had a direct inhibitory effect on the bacterial lipopolysacchride consequently leading to decreased inflammation and septic shock [30].

In addition, the combinational treatment of rifampicin and gentamicin in vivo proved to be more effective than treating with rifampicin alone, that is, treating the infected mice with an MIC dose of rifampicin first, followed later on by a bactericidal dose of the same drug. A potential reason behind this is a resistance to rifampicin that may have developed, and thus resulted in the ineffective outcome of using an MBC dose of rifampicin, as compared to that of gentamicin. Resistance to rifampicin by E. coli was reported shortly after rifampicin was discovered. Susceptible bacteria, like E. coli, develop resistance to rifampicin by one-step mutations that alter the subunit structure of the RNA-polymerase, and this takes place rapidly when rifampicin is used alone [20,31].

Conclusions

The present study indicates that treatment with rifampicin followed by gentamicin is capable of decreasing toxin expression in E. coli O157:H7 in vitro and improving the survival of mice infected with this organism. Further investigations should indicate cases where such a treatment modality would be of benefit. Antibacterial agents should therefore not be kept out of perspective for the treatment of E. coli O157:H7 among other Shiga toxin-producing organisms. However, care should be given to the selection of agents with the appropriate mechanism of action. The effect of these agents on toxin gene expression should be taken into account. Agents that limit toxin production prior to eradicating the bacterial infection are preferable. This may be achieved by combination antimicrobial therapy such as the one described herein.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

EAR and GMM conceived and designed the study, monitored the progress and supervised and drafted the manuscript. NK carried out the in vitro and in vivo assays described herein and participated in drafting the manuscript. AS participated in designing and performing the real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. AMA participated in designing the in vivo monitoring aspects of this study and in manuscript revisions. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Elias A Rahal, Email: er00@aub.edu.lb.

Natalie Kazzi, Email: nonanat@msn.com.

Ahmad Sabra, Email: as110@aub.edu.lb.

Alexander M Abdelnoor, Email: aanoor@aub.edu.lb.

Ghassan M Matar, Email: gmatar@aub.edu.lb.

References

- Levine MM. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:377–389. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce TG, Swerdlow DL, Griffin PM. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:364–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508103330608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JN. The thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndromes: overview of pathogenesis (Experience of The Oklahoma TTP-HUS Registry, 1989-2007) Kidney Int Suppl. 2009. pp. S8–S10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:607–625. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel JM, Sparling PH, Crowe C, Griffin PM, Swerdlow DL. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreaks, United States, 1982-2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:603–609. doi: 10.3201/eid1104.040739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead PS, Griffin PM. Escherichia coli O157:H7. Lancet. 1998;352:1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MP. Structure-function analyses of Shiga toxin and the Shiga-like toxins. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90050-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood SB, Auclair F, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch GT, Mekalanos JJ. Nucleotide sequence of the Shiga-like toxin genes of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4364–4368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SL. Southwestern Internal Medicine Conference: Shiga-like toxins in hemolytic-uremic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med Sci. 1993;306:398–406. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199312000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallance BA, Finlay BB. Exploitation of host cells by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8799–8806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CM, Sinclair JF, Smith MJ, O'Brien AD. Shiga toxin of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli type O157:H7 promotes intestinal colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9667–9672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602359103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AO, Borczyk AA, Carlson JA, Harvey B, Hockin JC, Karmali MA, Krishnan C, Korn DA, Lior H. A severe outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7--associated hemorrhagic colitis in a nursing home. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1496–1500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712103172403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff SM, Kobayashi JM, Lewis JH. Infections with Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Washington State. The first year of statewide disease surveillance. JAMA. 1989;262:355–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavia AT, Nichols CR, Green DP, Tauxe RV, Mottice S, Greene KD, Wells JG, Siegler RL, Brewer ED, Hannon D. et al. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome during an outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections in institutions for mentally retarded persons: clinical and epidemiologic observations. J Pediatr. 1990;116:544–551. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walterspiel JN, Ashkenazi S, Morrow AL, Cleary TG. Effect of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on extracellular Shiga-like toxin I. Infection. 1992;20:25–29. doi: 10.1007/BF01704889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Ohta Y, Noda M. Shiga toxin 2 is specifically released from bacterial cells by two different mechanisms. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2813–2823. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00060-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matar GM, Rahal E. Inhibition of the transcription of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 genes coding for shiga-like toxins and intimin, and its potential use in the treatment of human infection with the bacterium. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97:281–287. doi: 10.1179/000349803235002146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanbar A, Rahal E, Matar GM. In Vitro Inhibition of the Expression of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Genes Encoding the Shiga-like Toxins by Antimicrobial Agents: Potential Use in the Treatment of Human Infection. J Appl Res. 2003;3:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Rahal EA, Kazzi N, Kanbar A, Abdelnoor AM, Matar GM. Role of rifampicin in limiting Escherichia coli O157:H7 Shiga-like toxin expression and enhancement of survival of infected BALB/c mice. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezekiel DH, Hutchins JE. Mutations affecting RNA polymerase associated with rifampicin resistance in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1968;220:276–277. doi: 10.1038/220276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinneman KC, Yoshitomi KJ, Weagant SD. Multiplex real-time PCR method to identify Shiga toxin genes stx1 and stx2 and Escherichia coli O157:H7/H- serotype. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:6327–6333. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.6327-6333.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Mao X, Li J, Li H, Feng Y, Chen H, Luo P, Gu J, Yu S, Zeng H. et al. Engineering an anti-Stx2 antibody to control severe infections of EHEC O157:H7. Immunol Lett. 2008;121:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Matsuoka K, Kita E, Okabe N, Mizuguchi M, Hino K, Miyazawa S, Yamasaki C, Aoki J, Takashima S. et al. A therapeutic agent with oriented carbohydrates for treatment of infections by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7669–7674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112058999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkovic A, Smigic N, Devlieghere F. Contemporary strategies in combating microbial contamination in food chain. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee KM, Kim WS, Lim J, Nam S, Youn M, Nam SW, Kim Y, Kim SH, Park W, Park S. Antipathogenic properties of green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate at concentrations below the MIC against enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Food Prot. 2009;72:325–331. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-72.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe A, Wu VC, Tyler S, Edwards K. Antimicrobial action of the American cranberry constituents; phenolics, anthocyanins, and organic acids, against Escherichia coli O157:H7. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;139:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Shimizu K, Nomoto K, Takahashi M, Watanuki M, Tanaka R, Tanaka T, Hamabata T, Yamasaki S, Takeda Y. Protective effect of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in infant rabbits. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1101–1108. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1101-1108.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oussalah M, Caillet S, Lacroix M. Mechanism of action of Spanish oregano, Chinese cinnamon, and savory essential oils against cell membranes and walls of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes. J Food Prot. 2006;69:1046–1055. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-69.5.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton-Celsa AR, O'Brien A. In: Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E coli strains. Kaper JB, O'Brien AD, editor. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Structure, biology, and relative toxicity of Shiga toxin family members for cells and animals; pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Barsoumian H, El-Rami F, Abdelnoor AM. The effect of five antibacterial agents on the physiological levels of serum nitric oxide in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reese RE, Betts RF. In: Handbook of antibiotics. Richard E Reese, Robert F Betts, editor. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, MA; 1993. Rifampin; pp. 359–369. [Google Scholar]