Abstract

African Americans (AA) tend to have heightened systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Endothelial microparticles (EMP) are released from activated/apoptotic endothelial cells (EC) when stimulated by inflammation. The purpose of our study was to assess EMP responses to inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α) and antioxidant (superoxide dismutase, SOD) conditions in human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) obtained from AA and Caucasians. EMPs were measured under four conditions: control (basal), TNF-α, SOD, and TNF-α + SOD. Culture supernatant was collected for EMP analysis by flow cytometry and IL-6 assay by ELISA. IL-6 protein expression was assessed by Western blot. AA HUVECs had greater EMP levels under the TNF-α condition compared to the Caucasian HUVECs (6.8 ± 1.1 vs 4.7% ± 0.4%, P = 0.04). The EMP level increased by 89% from basal levels in the AA HUVECs under the TNF-α condition (P = 0.01) compared to an 8% increase in the Caucasian HUVECs (P = 0.70). Compared to the EMP level under the TNF-α condition, the EMP level in the AA HUVECs was lower under the SOD only condition (2.9% ± 0.3%, P = 0.005) and under the TNF-α + SOD condition (2.1% ± 0.4%, P = 0.001). Basal IL-6 concentrations were 56.1 ± 8.8 pg/mL/μg in the AA and 30.9 ± 14.9 pg/mL/μg in the Caucasian HUVECs (P = 0.17), while basal IL-6 protein expression was significantly greater (P < 0.05) in the AA HUVECs. These preliminary observational results suggest that AA HUVECs may be more susceptible to the injurious effects of the proinflammatory cytokine, TNF-α.

Keywords: endothelium, inflammation, endothelial microparticles, African Americans

Video abstract

Video (38.1MB, avi)

Introduction

Endothelial dysfunction precedes hypertension and atherosclerosis1,2 and is a prognostic indicator of future cardiovascular events. In response to sensing hormonal, biochemical, and mechanical stimuli, the endothelium releases mediators of vascular function, initiates inflammatory processes, and influences homeostasis. In the US, African Americans experience higher mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD) including hypertension compared to Caucasians or Mexican Americans.3

An impaired endothelium is conventionally thought to be analogous to diminished nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation in response to endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) agonists such as acetylcholine or bradykinin. Currently, there is an expanded appreciation of endothelial dysfunction which includes a proinflammatory, pro-oxidant, and prothrombic EC state. Several studies have shown that African-Americans have impaired endothelial function as determined by flow-mediated dilation (FMD)4–6 and other measures of endothelial-dependent vasodilation.7–12

The mechanisms underlying racial disparities in CVD and endothelial dysfunction are multifactorial, but could be due, in part, to differences in endothelial cell (EC) responses to stimuli. However, a major problem with research on the racial disparity in endothelial dysfunction is that it is conducted at the organ or clinical levels and not at the cellular level. This lack of knowledge about the EC biology of African Americans severely impedes advances in finding optimal preventive and treatment strategies.

In response to proinflammatory cytokine stimulation, ECs undergo functional changes that include increased expression/production of IL-6 and adhesion molecules, and induction of procoagulant activity.13–15 African Americans have also been shown to have higher levels of inflammatory markers compared to Caucasians and this also may contribute to the greater CVD-related morbidity and mortality in this population.16–21 Studies have linked inflammation to EC activation, an early step in endothelial dysfunction, and loss of NO bioactivity.22 In a cell culture study, Kalinowski et al showed that human umbilical ECs (HUVECs) from African Americans had reduced NO bioavailability compared to Caucasian HUVECs primarily due to increased superoxide (O2−) production and eNOS uncoupling.23

Endothelial microparticles (EMP) are submicroscopic membranous particles that are released from activated or apoptotic parent EC when stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, or infectious agents.24 They carry with them a subset of membrane proteins and phospholipids, or markers, of their parent EC including those induced by activation, apoptosis or oxidative stress. Recent evidence indicates that EMPs provide valuable information about the biological status of the endothelium. Previous studies have shown that EMPs expressing constitutive surface markers such as CD31 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule; PECAM) are increased in injury and/or apoptosis.25 Results from both clinical and laboratory studies demonstrate that higher EMP levels are related to diminished endothelium-dependent vasodilation. The level of EMP appears to correlate with the degree of endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic renal failure26 or coronary artery disease.27 Thus, the level of EMPs is emerging as a novel direct marker of EC impairment mediated by activation and apoptosis28,29 and may provide new insight into the mechanisms of racial disparities in endothelial dysfunction. However, EMPs have never been used to assess potential racial differences in endothelial function.

Due to the hypothesized mechanisms leading to endothelial dysfunction and EC impairment in African Americans, the purpose of our study was to observe EMP responses to inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α) and antioxidant ( superoxide dismutase, SOD) conditions in HUVECs obtained from African Americans and Caucasians.

Methods

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

HUVECs were purchased from Lonza Inc (Walkersville, MD), who harvested ECs from umbilical cord donors (AA, n = 3; Caucasian, n = 3). Cryopreserved HUVECs were then shipped by Lonza as frozen primaries. The HUVECs were cultured in parallel, in EGM medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and growth factors (Lonza, Inc) at 37°C in a 95% air −5% CO2 atmosphere, following methods by Lonza. All Lonza HUVECs are characterized by morphological observation through serial passaging, positive test for von Willebrand Factor VIII and acetylated low density lipoprotein (LDL) uptake, and negative test for α-smooth muscle actin.

Experimental procedures

Human recombinant TNF-α was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO) and SOD was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ). Parallel HUVEC cultures were tested under four separate conditions: Control, TNF-α (100 U/mL) for 4 hours, SOD (100 U/mL) for 24 hours, and TNF-α + SOD. 100 U/mL of TNF-α was selected because it is a typical level used to stimulate ECs and falls approximately midway between the highest and lowest levels used to stimulate ECs in similar studies.30–35 Culture media samples (4 mL) obtained from 106 ECs were collected and immediately frozen at −80°C for subsequent EMP analysis.25,36 Remaining culture supernatant was collected for IL-6 assay.

Cell lysate was collected by cellular fractionation for total SOD activity measurements. Briefly, cells were washed once with ice-cold phosphate buffer solution, and resuspended in 2 mL cold 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer (Lonza) using a rubber scraper. Cells were centrifuged at 600g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μL cold HEPES buffer and then transferred to a Teflon glass homogenizer. The cell solution was homogenized at 1600 rpm for 30 strokes while on ice, and then immediately centrifuged at 1500g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford method.

For all procedures, AA and Caucasian HUVECs at passage 4 were treated identically. For assay, experimental samples were tested in duplicate and control samples of culture media were tested along with the cell samples in order to eliminate potential interference from culture media in measurements. Absorbance was read using a SpectraMax Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

EMP immunolabeling

Microparticles express several different cell surface markers which can be quantified. The preferred method is the 2-color combination of phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-CD31 with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-CD42. Because CD31 is also found on platelets, platelet-specific CD42 allows counting the platelet microparticles population (CD31+, CD42+) distinct from EMP (CD31+, CD42−), giving both counts in a single run. This pair of markers has the advantage of being very bright and therefore sensitive.29 EMP samples were prepared as previously described.37,38

To remove unwanted cellular fragments, thawed culture media (1.5 mL) was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 4300g (20°C). Supernatant was removed and transferred into a new tube and centrifuged for 90 minutes at 3152g (20°C). 100 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and incubated with 20 μL of anti-human CD31+ (PE) and 20 μL of anti CD42 (FITC) in the dark at room temperature (30 minutes), then fixed by adding 93 μL of 10% formaldehyde. The mixture was protected from light and incubated while being gently mixed for 20 minutes using a shaker. Samples were diluted in 500 μL of double-filtered (0.22 μm) PBS for a total sample volume of 733 μL. Two additional tubes were prepared to serve as a negative control and as a calibration. For the negative control tube, 733 μL of PBS was added to one tube. To prepare the calibrator sample, two drops of 0.9 μm standard precision NIST traceable polystyrene particle beads ( Polysciences Inc, Warrington PA) were added to PBS according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were then immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Labeled EMP produced by 106 ECs were analyzed using an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed with BD FACSDiva software (v 1.2.6; BD Biosciences). There is no consensus on the threshold level setting which determines the smallest size microparticle analyzed, therefore we set the threshold levels based on the number of background events per second when double-filtered PBS was passed through the flow cytometer as reported by Orozco and Lewis.39 The upper limit of gate was determined by 0.9 μm standard beads. CD31+/ C42− events included in this gate were identified in forward and side scatter intensity dot representation and plotted on 2-color fluorescence histograms and were considered EMP.5,40,41–43 From each 50 μL sample, the percentage of EMP from 50,000 total events was recorded.40,41 Before every run, the machine was kept running until the background events fell to baseline levels. The final EMP values were then expressed as % total events40 normalized to protein content (μg/μL). The inter- and intra-assay CVs were 8% and 6%, respectively.

Western blot for IL-6 protein

HUVECs were washed twice in ice-cold Hanks buffered saline solution and lysed in Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay Buffer with Roche protease inhibitor (RIPA-Pi). Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride protease inhibitor was also added to the RIPA-Pi to eliminate interference. At confluence, cells were collected, centrifuged at 16,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Quantification of protein content was measured by Bradford assay. 20 μg of protein was separated by electrophoresis through 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose filter membranes. Membranes were blocked with non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C. Subsequently, the membranes were washed and then incubated with secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Immunoreactive proteins were detected by chemiluminescence with Thermo Scientific SuperSignal substrate systems (Pierce Biotechnology). Anti-IL-6 (Abcam, Inc, MA). Actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used as the internal control. Band densitometry analysis was performed using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software.

Assay for superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

Total SOD activity was measured in order to have an assessment of the cell’s potential for superoxide quenching. Total SOD activity in cell lysate samples by assay (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), as previously reported.42 Concentrations were normalized to protein content (μg/μL). Inter-assay and intra-assay CVs were 5.9% and 12.4%, respectively.

Assay for IL-6

IL-6 proteins released into media were measured in cell culture supernatants by ELISA (Thermo Scientific-Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations were normalized to protein content (μg/μL). The intra- and inter-assay CVs were 9% and 10%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All values were presented as means ± SE. Two-way (ethnicity by condition) and one-way (within ethnicity and within experimental condition) ANOVA followed by Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) were performed for statistical comparisons. An independent t-test was used to compare band densities for IL-6 expression between AA and Caucasian HUVECs. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

HUVEC morphology under all experimental conditions

Representative images of AA and Caucasian HUVECs at confluency under all experimental conditions are shown in Figure 1. HUVECs displayed a cobblestone-like shape. There were no morphological differences between the AA and Caucasian HUVECs.

Figure 1.

Representative images of African American and Caucasian HUVECs at harvest under all experimental conditions.

Abbreviations: HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TNF-α, tissue necrosis factor alpha.

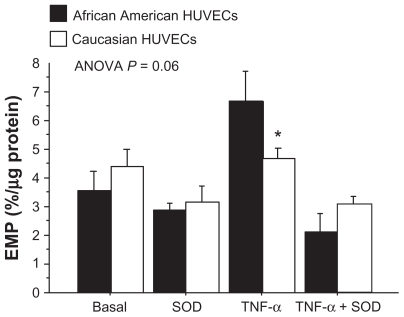

EMP levels under basal conditions

Figure 2 shows comparisons of EMP levels between AA and Caucasian HUVECs under all experimental conditions. There were no significant differences in EMP levels under basal conditions between AA (3.6% ± 0.7%) and Caucasian (4.4% ± 0.6%) HUVECs (P = 0.38).

Figure 2.

Comparison of EMP levels between the African American and Caucasian HUVEC groups under each of the experimental conditions.

Note: *P < 0.05 between HUVEC racial groups.

Abbreviations: HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; SOD, superoxide dismutase, EMP, endothelial microparticles; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

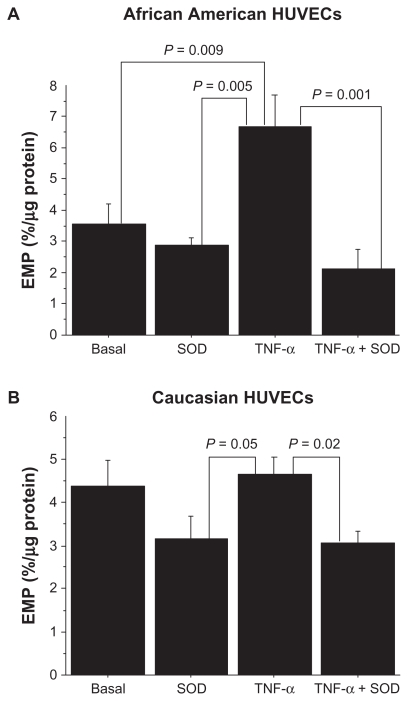

Effects of TNF-α stimulation and SOD on EMP generation

TNF-α is a potent inducer of inflammatory reactions and oxidative stress in EC. When the levels of EMPs were analyzed by experimental condition (AA and Caucasian HUVEC responses combined), TNF-α significantly increased EMP from the basal level of 3.9% ± 0.4% to 5.7% ± 0.6% (P = 0.01). Compared to the basal EMP level, SOD decreased the EMP level to 3.0% ± 0.5% (P = 0.19). Compared to the TNF-α condition, the addition of SOD significantly reduced the EMP level to 3.0 ± 0.3 (P < 0.0001). The EMP levels under the SOD only condition (3.0 ± 0.3) and the TNF-α + SOD condition (2.6 ± 0.3) were not different.

The interactive effect of HUVEC race and experimental condition was borderline significant (P = 0.06, Figure 2). Post hoc analyses showed that AA HUVECs had a significantly greater level of EMP under the TNF-α condition compared to the Caucasian HUVECs (6.8 ± 1.1 vs 4.7% ± 0.4%, P = 0.04). Within the AA HUVECs, the EMP level increased by 89% from a basal level of 3.5 ± 0.7 to 6.8% ± 1.1% under the TNF-α condition (P = 0.01) (Figure 3A). Compared to the EMP level under the TNF-α condition, the EMP level was significantly lower under the SOD only condition (2.9% ± 0.3%, P = 0.005) and under the TNF-α + SOD condition (2.1% ± 0.4%, P = 0.001). Within the Caucasian HUVECs, there was only an 8% increase in the EMP level from the basal condition to the TNF-α condition (P = 0.70) (Figure 3B). The only significant difference in EMP levels in the Caucasian HUVECs was between the TNF-α (4.7% ± 0.4%) and the TNF-α + SOD condition (3.0% ± 0.3%, P = 0.02). The difference in the level of EMP between the TNF-α condition (4.7 ± 0.4) and the SOD condition (3.2 ± 1.0) was borderline significant (P = 0.05).

Figure 3.

A) EMP levels under each of the experimental conditions in African American HUVECs. B) EMP levels under each of the experimental conditions in Caucasian HUVECs.

Abbreviations: HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; SOD, superoxide dismutase, EMP, endothelial microparticles.

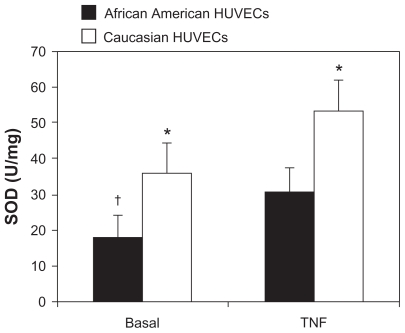

Total SOD activity under basal and TNF-α conditions

Total SOD activity in AA and Caucasian HUVECs under basal and TNF-α conditions are shown in Figure 4. Basal SOD activity levels were (17.2 ± 12.0 U/mg) in the AA HUVECs and (35.8 ± 17.2 U/mg) the Caucasian HUVECs (P = 0.03). Compared to the basal levels, TNF-α stimulation caused a significant increase in SOD activity in the AA HUVECs (P = 0.04), while no significant change occurred with TNF-α stimulation in Caucasian HUVECs (P = 0.09).

Figure 4.

Total SOD activity under basal and TNF-α conditions in African American and Caucasian HUVECs.

Notes: *P < 0.05 between HUVEC racial groups within condition; †P < 0.05 compared to TNF-α condition within racial HUVEC groups.

Abbreviations: HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TNF-α, tissue necrosis factor alpha.

IL-6 concentrations under basal conditions

IL-6 concentrations in AA and Caucasian HUVECs under all experimental conditions are shown in Figure 5. Basal IL-6 concentrations were (56.1 ± 8.8 pg/mL/μg) in the AA HUVECs and (30.9 ± 14.9 pg/mL/μg) the Caucasian HUVECs (P = 0.17). Given the nearly two-fold higher basal IL-6 concentration in the AA HUVECs, we wanted to confirm whether IL-6 protein expression was greater. Representative Western blots for IL-6 protein under basal conditions are shown in Figure 5. Basal IL-6 protein expression was significantly greater in the AA HUVECs compared to the Caucasian HUVECs. This confirmed the greater basal IL-6 concentrations in the culture media of AA HUVECs.

Figure 5.

IL-6 concentrations under each of the experimental conditions in African American and Caucasian HUVECs.

Notes: *P < 0.05 between HUVEC racial groups within condition; †P < 0.05 compared to TNF-α condition within racial HUVEC groups. At the top are representative Western blots of basal IL-6 protein expression levels in African American and Caucasian basal HUVECs.

Abbreviations: HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TNF-α, tissue necrosis factor alpha; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Effects of TNF-α stimulation and SOD on IL-6 concentrations and protein expression

The binding of TNF-α to its receptor on EC induces down-stream gene expression of IL-6, which can influence EC function and cause increased adhesion and chemokine expression and apoptosis. When the levels of IL-6 were analyzed by experimental condition (AA and Caucasian HUVEC responses combined), IL-6 concentration increased from 44.9 ± 8.8 pg/mL/μg protein under basal conditions to 62.6 ± 10.6 pg/mL/μg protein under TNF-α stimulation, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.14). There were no significant differences in IL-6 concentrations between any of the other conditions. The interactive effect of HUVEC race and condition was not statistically significant (P = 0.43) (Figure 5). Within the AA HUVECs, the IL-6 concentration under the SOD condition tended to lower compared to the TNF-α condition (40.0 ± 8.0 vs 70.8 ± 15.7 pg/mL/μg, P = 0.07) (Figure 5). Within the Caucasian HUVECs, there were no significant differences in IL-6 concentrations between any of the experimental conditions (Figure 4).

Discussion

The most important finding of this preliminary observational study was that for the first time we showed that TNF-α-stimulated EMP generation was different between African American and Caucasian HUVECs. AA HUVECs demonstrated an 89% increase in EMP generation as a result of TNF-α stimulation compared to an 8% increase in EMP generation in the Caucasian HUVECS. This finding is important because it is generally thought that for any given level of BP, African Americans have a greater degree of endothelial dysfunction compared to Caucasians and because the measurement of the EMP expression of marker CD31 is linked to EC activation/apoptosis. Therefore, these observations suggest that AA HUVECs have greater EC damage from TNF-α stimulation.

Microparticles are not released randomly into the circulation. 43 Activation or injury of the endothelium leads to various inflammatory-related processes including the release of microparticles. Combes et al were the first to demonstrate that HUVECs release EMP when stimulated with TNF-α.24 Other proinflammatory, prothrombotic, proapoptotic, or oxidative substances also induce the release of EMP.28,44 EMP express adhesion molecules specific for mature ECs such as CD54 (ICAM-1), CD62E (E-selectin), CD62P (P-selectin), or CD31 (PECAM).28,29 CD31 is also expressed by platelet-derived microparticles, therefore EMP specificity is ensured by the CD31+/CD41− phenotype with CD41 being the platelet integrin GPIIbIIIa.28,29 Studies have demonstrated that EMP can be used as a novel biomarker of endothelial injury that directly reflects the homeostatic state of the endothelium.29,45–49 To our knowledge, no study has used EMPs as an index of endothelial cell status to assess potential racial differences in EC function.

TNF-α stimulation caused a significant 89% increase in EMP level in AA HUVECs and a nonsignificant 8% increase in EMP level in the Caucasian HUVECs. The EMP levels under TNF-α stimulation were significantly different between the HUVEC groups. Based on these results, it appears that AA HUVECs were more susceptible to the damaging effects of TNF-α. Plasma TNF-α concentrations have been associated with early atherosclerosis.50 Moreover, there are reports that African Americans have higher systemic levels of inflammatory biomarkers16–21 which suggests that at least a portion of their endothelial dysfunction may be secondary to cytokine-induced endothelial activation/ apoptosis.

The endothelium has several important functions related to cardiovascular health. Functional changes of the activated endothelium include disturbance of the regulation of vessel tone and the maintenance of a vascular environment that favors coagulation, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. EMP levels are increased in hypertension and a significant correlation was shown between EMP and blood pressure.46 It is thought that African Americans have lower endothelial NO bioavailability than Caucasians based on findings of attenuated flow-mediated arterial vasodilatation.4–6 Other investigations have also documented lower endothelial-dependent vasodilation in African Americans.8–11,51,52

TNF-α can induce endothelial dysfunction through both inflammatory and oxidative stress mechanisms. TNF-α activates the p38 MAPK pathway53 and the transcription factor, NF-κB, which regulates the expression of genes involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction.54–56 Inflammatory cytokines induce the expression of adhesion molecules and chemoattractants by ECs. Gertzberg et al and Yamagishi et al showed that in response to TNF-α, EC NADPH oxidase activity increased, leading to increased O2− production.57,58 Under normal physiological conditions, the dismutation of O2− by SOD yields H2O2. In the case of heightened NADPH oxidase activity and O2− overproduction, O2− reacts with NO to produce ONOO− thus reducing NO bioavailability.59 In order to assess the potential for O2− dismutation in the present study, total SOD activity was measured in cell lysate from both basal and TNF-α stimulated AA and Caucasian HUVECs. We observed significantly higher SOD activity in the Caucasian HUVECs under both conditions. The AA HUVECs had a 79% increase in SOD activity compared to a 50% increase in Caucasian HUVECs. This could suggest a higher oxidative stress response to the TNF-α stimulation which is also evidenced by the heightened EMP production with TNF-α stimulation in the African American HUVECs.

In the present study, we also measured EMP levels after incubation of the HUVECs with SOD alone and after incubation with TNF-α + SOD. The response to SOD alone was similar in both groups of HUVECs. Though both the AA and Caucasian HUVECs showed a significant decrease in EMP levels when the TNF-α + SOD condition was compared to the TNF-α alone condition, the AA HUVECs showed a 68% decrease in EMP levels whereas the Caucasian HUVECs showed a 35% decrease in EMP level. These results suggest that TNF-α-induced oxidative stress played a greater role in EMP generation in AA compared to Caucasian HUVECs because the effect of SOD was nearly twice that of the Caucasian HUVECs.

The proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α also induces EC gene expression and production of IL-6 via the NF-κB pathway. 58 IL-6 is a secondary inflammatory cytokine that mediates the regulation of the acute-phase response to injury and infection. IL-6 induces the increase of plasma concentrations of fibrinogen, PAI-1, and CRP. Evidence indicates that the elevation of CRP predicts future cardiovascular events.60

In the present study, we observed that the AA HUVECs had nearly a two-fold greater basal IL-6 concentration compared to the Caucasian HUVECs. Western blot analysis of basal IL-6 expression showed that the AA HUVECs had significantly greater IL-6 protein expression. The IL-6 response to SOD was also different between the HUVEC groups. SOD decreased IL-6 concentration in the AA HUVECs but increased IL-6 concentration in the Caucasian HUVECs. The reasons for the disparate IL-6 response to SOD are not clear. Incubating the HUVECs with TNF-α + SOD similarly decreased IL-6 concentrations compared to incubation with TNF-α alone. These changes were similar in both HUVEC groups. In healthy men, elevated levels of IL-6 were associated with increased future CVD risk, endothelial dysfunction, and hypertension.61–63 Epidemiologic data support the existence of an association between different inflammatory markers and high blood pressure.64,65

The normal functional integrity of ECs is maintained by continuous cell regeneration and the incorporation of endothelial progenitor cells. Under these normal quiescent conditions, EC activation tends to be localized, low-grade, and reversible. The level of circulating EMP is very low when ECs are quiescent.66 The exposure of the endothelium to cytokines causes vascular inflammation by inducing EC activation and apoptosis. There is a tendency for African Americans to have heightened systemic inflammation as measured by various inflammatory biomarkers.16–21 Long-term exposure of the endothelium to proinflammatory cytokines leads to increased oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis, and promotes leukocyte infiltration and thrombosis. All of these changes to ECs cause vascular dysfunction and support an EC environment favoring hypertension and atherosclerosis.

The aim of this observational study was to assess ECs that have not been exposed to chronic diseases in order to assess their fundamental response to stimuli. The HUVECs were purchased from Lonza Inc in which only the racial origin is known, due to The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which protects the privacy of individually identifiable health information. HUVECs are derived from fetal tissue which makes them better suited for measuring fundamental responses to stimuli because adult ECs may have been subjected to prolonged exposure to cytokines, hormones, and other stimuli, potentially resulting in an altered phenotype.67 An EC obtained from a newborn has already developed to the point where it is suitable for its particular function. One study found that out of the potentially confounding variables such as the interval between delivery and cell isolation, sex and weight of newborn, type of delivery, age, smoking habits, diabetes, or hypertension of the mother, only the short time between delivery and cell isolation and the mother’s smoking habits lead to alterations in cell culture success rate68 and morphology.69 Thus while we do not know the specific characteristics of the mothers, we believe that the HUVECs were relatively unaffected by the mother.

There are several limitations of the study that are worth noting. First, we did not directly measure the levels of the superoxide radical. The measurement of total SOD activity provides insight into the cell’s potential for superoxide quenching. Second, we only incubated the cells with TNF-α for 4 hours. This was done in order to avoid significant apoptosis. Lastly, the present observational study cannot provide insight into potential mechanisms for heightened EC susceptibility to TNF-α in AA HUVECs but it may lie in differences in TNF-α receptor sensitivity and/or post-receptor signaling mechanisms.

The preliminary results of our study suggest that AA HUVECs are more susceptible to the injurious effects of the proinflammatory cytokine, TNF-α. In addition, the results suggest that TNF-α-induced oxidative stress plays a greater role in EMP generation in AA compared to Caucasian HUVECs. If African Americans tend to have a subclinical heightened state of chronic systemic low-grade inflammation, then the manner in which their ECs respond to inflammatory cytokines could make them more susceptible to long-term endothelial dysfunction and its sequelae such as hypertension and atherosclerosis. This warrants the importance of aggressive preventive lifestyle modification strategies in African Americans in early subclinical stages of hypertension development to reduce the inflammation and oxidative stress burdens.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Taddei S, Virdis A, Mattei P, Ghiadoni L, Sudano I, Salvetti A. Defective L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway in offspring of essential hypertensive patients. Circulation. 1996;94(6):1298–1303. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R. Atherosclerosis – an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perregaux D, Chaudhuri A, Rao S, et al. Brachial vascular reactivity in blacks. Hypertension. 2000;36(5):866–871. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campia U, Choucair WK, Bryant MB, Waclawiw MA, Cardillo C, Panza JA. Reduced endothelium-dependent and -independent dilation of conductance arteries in African Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(4):754–760. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones DS, Andrawis NS, Abernethy DR. Impaired endothelial-dependent forearm vascular relaxation in black Americans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;65(4):408–412. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Cannon RO, 3rd, Panza JA. Racial differences in nitric oxide-mediated vasodilator response to mental stress in the forearm circulation. Hypertension. 1998;31(6):1235–1239. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang CC, Stein CM, Brown RM, et al. Attenuation of isoproterenol-mediated vasodilatation in blacks. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(3):155–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507203330304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbaum DA, Pretorius M, Gainer JV, et al. Ethnicity affects vasodilation, but not endothelial tissue plasminogen activator release, in response to bradykinin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(6):1023–1028. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000017704.45007.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gainer JV, Stein CM, Neal T, Vaughan DE, Brown NJ. Interactive effect of ethnicity and ACE insertion/deletion polymorphism on vascular reactivity. Hypertension. 2001;37(1):46–51. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn DF, Duffy SJ, Tomasian D, et al. Effects of black race on forearm resistance vessel function. Hypertension. 2002;40(2):195–201. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000024571.69634.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein CM, Lang CC, Nelson R, Brown M, Wood AJ. Vasodilation in black Americans: attenuated nitric oxide-mediated responses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;62(4):436–443. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanden Berghe W, Vermeulen L, De Wilde G, De Bosscher K, Boone E, Haegeman G. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor and gene regulation of the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60(8):1185–1195. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackay F, Loetscher H, Stueber D, Gehr G, Lesslauer W. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha)-induced cell adhesion to human endothelial cells is under dominant control of one TNF receptor type, TNF-R55. J Exp Med. 1993;177(5):1277–1286. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nawroth PP, Stern DM. Modulation of endothelial cell hemostatic properties by tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med. 1986;163(3):740–745. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.3.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lampert R, Ickovics J, Horwitz R, Lee F. Depressed autonomic nervous system function in African Americans and individuals of lower social class: a potential mechanism of race- and class-related disparities in health outcomes. Am Heart J. 2005;150(1):153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haren MT, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, et al. Higher C-reactive protein and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor levels are associated with poor physical function and disability: a cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of late middle-aged African Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(3):274–281. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox ER, Benjamin EJ, Sarpong DF, et al. Epidemiology, heritability, and genetic linkage of C-reactive protein in African Americans (from the Jackson Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(7):835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doumatey AP, Lashley KS, Huang H, et al. Relationships among obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance in African Americans and West Africans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(3):598–603. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slopen N, Lewis TT, Gruenewald TL, et al. Early life adversity and inflammation in African Americans and whites in the midlife in the United States survey. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(7):694–701. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e9c16f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai S, Fishman EK, Lai H, Pannu H, Detrick B. Serum IL-6 levels are associated with significant coronary stenosis in cardiovascularly asymptomatic inner-city black adults in the US. Inflamm Res. 2009;58(1):15–21. doi: 10.1007/s00011-008-8150-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang AL, Vita JA. Effects of systemic inflammation on endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalinowski L, Dobrucki IT, Malinski T. Race-specific differences in endothelial function: predisposition of African Americans to vascular diseases. Circulation. 2004;109(21):2511–2517. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129087.81352.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combes V, Simon AC, Grau GE, et al. In vitro generation of endothelial microparticles and possible prothrombotic activity in patients with lupus anticoagulant. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(1):93–102. doi: 10.1172/JCI4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng B, Chen Y, Luo Y, Chen M, Li X, Ni Y. Circulating level of microparticles and their correlation with arterial elasticity and endothelium-dependent dilation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208(1):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amabile N, Guerin AP, Leroyer A, et al. Circulating endothelial microparticles are associated with vascular dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3381–3388. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werner N, Wassmann S, Ahlers P, Kosiol S, Nickenig G. Circulating CD31+/annexin V+ apoptotic microparticles correlate with coronary endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(1):112–116. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000191634.13057.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chironi GN, Boulanger CM, Simon A, Dignat-George F, Freyssinet JM, Tedgui A. Endothelial microparticles in diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335(1):143–151. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horstman LL, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Ahn YS. Endothelial microparticles as markers of endothelial dysfunction. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1118–1135. doi: 10.2741/1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai PF, Mohamed F, Monge JC, Stewart DJ. Downregulation of eNOS mRNA expression by TNF-alpha: identification and functional characterization of RNA-protein interactions in the 3′UTR. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59(1):160–168. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li JM, Mullen AM, Yun S, et al. Essential role of the NADPH oxidase subunit p47(phox) in endothelial cell superoxide production in response to phorbol ester and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circ Res. 2002;90(2):143–150. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.103615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li JM, Fan LM, Christie MR, Shah AM. Acute tumor necrosis factor alpha signaling via NADPH oxidase in microvascular endothelial cells: role of p47phox phosphorylation and binding to TRAF4. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(6):2320–2330. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2320-2330.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kataoka H, Murakami R, Numaguchi Y, Okumura K, Murohara T. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers prevent tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated endothelial nitric oxide synthase reduction and superoxide production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;636:1–3. 36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franzen B, Duvefelt K, Jonsson C, et al. Gene and protein expression profiling of human cerebral endothelial cells activated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;115(2):130–146. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Keulenaer GW, Ushio-Fukai M, Yin Q, et al. Convergence of redox-sensitive and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 induction in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(2):385–391. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heiss C, Amabile N, Lee AC, et al. Brief secondhand smoke exposure depresses endothelial progenitor cells activity and endothelial function: sustained vascular injury and blunted nitric oxide production. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(18):1760–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piccin A, Murphy WG, Smith OP. Circulating microparticles: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Blood Rev. 2007;21(3):157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang JM, Wang Y, Huang JY, et al. C-Reactive protein-induced endothelial microparticle generation in HUVECs is related to BH4-dependent NO formation. J Vasc Res. 2007;44(3):241–248. doi: 10.1159/000100558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orozco AF, Lewis DE. Flow cytometric analysis of circulating microparticles in plasma. Cytometry A. 2010;77(6):502–514. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macey MG, Enniks N, Bevan S. Flow cytometric analysis of microparticle phenotype and their role in thrombin generation. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2011;80(1):57–63. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gelderman MP, Simak J. Flow cytometric analysis of cell membrane microparticles. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;484:79–93. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-398-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feairheller DL, Sturgeon KM, Diaz KM, et al. Prehypertensive African-American women have preserved nitric oxide and renal function but high cardiovascular risk. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2010;33(4):282–290. doi: 10.1159/000317944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blann A, Shantsila E, Shantsila A. Microparticles and arterial disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35(5):488–496. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1234144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leroyer AS, Anfosso F, Lacroix R, et al. Endothelial-derived microparticles: biological conveyors at the crossroad of inflammation, thrombosis and angiogenesis. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(3):456–463. doi: 10.1160/TH10-02-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preston RA, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, et al. Effects of severe hypertension on endothelial and platelet microparticles. Hypertension. 2003;41(2):211–217. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000049760.15764.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koga H, Sugiyama S, Kugiyama K, et al. Elevated levels of VEcadherin-positive endothelial microparticles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(10):1622–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernal-Mizrachi L, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, et al. High levels of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2003;145(6):962–970. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heloire F, Weill B, Weber S, Batteux F. Aggregates of endothelial microparticles and platelets circulate in peripheral blood. Variations during stable coronary disease and acute myocardial infarction. Thromb Res. 2003;110(4):173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jimenez JJ, Jy W, Mauro LM, Horstman LL, Ahn YS. Elevated endothelial microparticles in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: findings from brain and renal microvascular cell culture and patients with active disease. Br J Haematol. 2001;112(1):81–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skoog T, Dichtl W, Boquist S, et al. Plasma tumour necrosis factor-alpha and early carotid atherosclerosis in healthy middle-aged men. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(5):376–383. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Cannon RO, Panza JA. Attenuation of cyclic nucleotide-mediated smooth muscle relaxation in blacks as a cause of racial differences in vasodilator function. Circulation. 1999;99(1):90–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steinberg HO, Bayazeed B, Hook G, Johnson A, Cronin J, Baron AD. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with cholesterol levels in the high normal range. Circulation. 1997;96(10):3287–3293. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curtis AM, Wilkinson PF, Gui M, Gales TL, Hu E, Edelberg JM. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase targets the production of proinflammatory endothelial microparticles. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(4):701–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.dela Paz NG, Simeonidis S, Leo C, Rose DW, Collins T. Regulation of NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression by the POU domain transcription factor Oct-1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(11):8424–8434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rimbach G, Valacchi G, Canali R, Virgili F. Macrophages stimulated with IFN-gamma activate NF-kappa B and induce MCP-1 gene expression in primary human endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;3(4):238–242. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.2000.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar A, Takada Y, Boriek AM, Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-kappaB: its role in health and disease. J Mol Med. 2004;82(7):434–448. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0555-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gertzberg N, Neumann P, Rizzo V, Johnson A. NAD(P)H oxidase mediates the endothelial barrier dysfunction induced by TNF-alpha. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286(1):L37–48. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00116.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, Nakamura K, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits TNF-alpha-induced interleukin-6 expression in endothelial cells by suppressing NADPH oxidase-mediated reactive oxygen species generation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37(2):497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darley-Usmar V, White R. Disruption of vascular signalling by the reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide: implications for cardiovascular disease. Exp Physiol. 1997;82(2):305–316. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101(15):1767–1772. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Pfeffer M, Sacks F, Lepage S, Braunwald E. Elevation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and increased risk of recurrent coronary events after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101(18):2149–2153. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.18.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brevetti G, Silvestro A, Schiano V, Chiariello M. Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular risk prediction in peripheral arterial disease: additive value of flow-mediated dilation to ankle-brachial pressure index. Circulation. 2003;108(17):2093–2098. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095273.92468.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rifai N, Joubran R, Yu H, Asmi M, Jouma M. Inflammatory markers in men with angiographically documented coronary heart disease. Clin Chem. 1999;45(11):1967–1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chae CU, Lee RT, Rifai N, Ridker PM. Blood pressure and inflammation in apparently healthy men. Hypertension. 2001;38(3):399–403. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Rifai N, Blake GJ, Gaziano JM, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein and the risk of developing hypertension. JAMA. 2003;290(22):2945–2951. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leroyer AS, Isobe H, Leseche G, et al. Cellular origins and thrombogenic activity of microparticles isolated from human atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(7):772–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tan PH, Chan C, Xue SA, et al. Phenotypic and functional differences between human saphenous vein (HSVEC) and umbilical vein (HUVEC) endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173(2):171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balconi G, Pietra A, Busacca M, de Gaetano G, Dejana E. Success rate of primary human endothelial cell culture from umbilical cords is influenced by maternal and fetal factors and interval from delivery. In Vitro. 1983;19(11):807–810. doi: 10.1007/BF02618159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Asmussen I, Kjeldsen K. Intimal ultrastructure of human umbilical arteries. Observations on arteries from newborn children of smoking and nonsmoking mothers. Circ Res. 1975;36(5):579–589. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]