Abstract

Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) has emerged as a key mediator in the mechanisms of ischaemic tolerance induced by a wide variety of preconditioning stimuli. NO is involved in the brain protection that develops either early (minutes–hours) or late (days–weeks) after the preconditioning stimulus. However, the sources of NO and the mechanisms underlying the protective effects differ substantially. While in early preconditioning NO is produced by the endothelial and neuronal isoform of NO synthase, in delayed preconditioning NO is synthesized by the inducible or ‘immunological’ isoform of NO synthase. Furthermore, in early preconditioning, NO acts through the canonical cGMP pathway, possibly through protein kinase G and opening of mitochondrial KATP channels. In late preconditioning, the protection is mediated by peroxynitrite formed by the reaction of NO with superoxide derived from the enzyme NADPH oxidase. The mechanisms by which peroxynitrite exerts its protective effect may include improvement of post-ischaemic cerebrovascular function, leading to enhancement of blood flow to the ischaemic territory, and expression of prosurvival genes resulting in cytoprotection. The evidence suggests that NO can engage highly effective and multifunctional prosurvival pathways, which could be exploited for the prevention and treatment of cerebrovascular pathologies.

Costantino Iadecola, MD, is the G. C. Cotzias Distinguished Professor of Neurology and Neuroscience and Chief of the Division of Neurobiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City. His research focuses on neurovascular regulation, the molecular pathology of ischaemia, and on the interface between stroke and Alzheimer's disease. He has published over 200 papers. He has served on the Research Committee of the AHA and on the Stroke Council. He has chaired the International Stroke Conference, is President (Chair) of the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Fondation Leducq and an advisor to the Canadian, European and German Stroke Networks. He is consulting editor for Stroke, reviewing editor for The Journal of Neuroscience, and guest editor for PNAS and Circulation. He is on the editorial board of the Annals of Neurology, the American Journal of Physiology (Heart Circ Physiol), Cerebrovascular Diseases, and the Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. He has received the Laurence McHenry Award (AAN), the Louis Sklarow Memorial Award, the Established Investigator Award (AHA), and the Jacob Javits Award (NINDS). In 2009, he received the Willis Award, the highest honour bestowed by the AHA in stroke research.

|

Introduction

Organisms face various destructive threats, such as infection, ischaemia or trauma, and, consequently, have developed mechanisms for self-protection from tissue damage. In this context, the term ‘preconditioning’ describes a process by which a potentially harmful stimulus ameliorates tissue damage when applied in a sub-lethal fashion before the injury. For example, short periods of non-lethal cerebral ischaemia reduce the brain damage produced by a subsequent lethal ischaemic insult (Gidday, 2006). This phenomenon, called ischaemic tolerance, was first reported in vivo in 1964 (Dahl & Balfour, 1964) and is fittingly described by the quote of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche: ‘What does not destroy me makes me stronger’ (Nietzsche, 2007).

Preconditioning can be induced by a wide variety of stimuli, including hypoxia-ischaemia, anaesthetics, hyperthermia, cortical spreading depressions, mitochondrial toxins, or proinflammatory agents, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Gidday, 2006). Tolerance can develop minutes to hours after the preconditioning stimulus (early preconditioning). Early preconditioning does not require protein synthesis and depends on signalling pathways activated by the preconditioning stimulus (Stagliano et al. 1999; Orio et al. 2007). A longer-lasting type of tolerance (delayed or late preconditioning) occurs days after the inducing stimulus and can last for weeks (Reis et al. 1998; Gidday, 2006; Stowe et al. 2011). Delayed preconditioning requires de novo protein synthesis (Kitagawa et al. 1990). The mechanisms of preconditioning have been studied extensively and have been recently reviewed (Perez-Pinzon et al. 2005; Gidday, 2006; Stenzel-Poore et al. 2007; Dirnagl et al. 2009). The evidence suggests that preconditioning is mediated by multiple pathways that act in concert to protect the brain by reducing energy expenditures, improving the delivery of blood flow, suppressing the pathogenic pathways triggered by cerebral ischaemia, and maximizing the repair potential of the damaged tissue (Dirnagl et al. 2009). In the context of delayed preconditioning, these effects are associated with, and perhaps driven by, a profound reprogramming of post-ischaemic gene expression (Stenzel-Poore et al. 2003).

Among the many factors involved in the complex chain of events leading to ischaemic preconditioning, nitric oxide (NO), a pleiotropic mediator implicated both in cell death and survival, has emerged as a key player. The purpose of this brief review is to examine the role of NO in ischaemic tolerance and to evaluate the potential translational relevance of using manipulations of the NO system to protect the brain from the consequences of cerebral ischaemia. A more comprehensive appraisal of this topic can be found in several excellent reviews (Gidday, 2006; Stenzel-Poore et al. 2007; Dirnagl et al. 2009).

Nitric oxide: sources, targets and reactions with oxygen radicals

NO is synthesized from l-arginine and oxygen by the oxidoreductase nitric oxide synthase, an enzyme present in three isoforms: neuronal NOS (nNOS), endothelial NOS (eNOS) and inducible or ‘immunological’ NOS (iNOS) (Alderton et al. 2001). NO exerts its biological effects by reacting with oxygen, superoxide, or transitional metal centres (Gross & Wolin, 1995; Pacher et al. 2007). These reactions support additional nitrosative reactions (reaction of NO+) with thiol groups that induce post-translational modifications of proteins (nitrosylation) (Stamler et al. 1992). NO reacts with haem groups of enzymes, such as guanylyl cyclase, leading to modulation of enzymatic activity (Gross & Wolin, 1995). However, NO has the greatest affinity for the free radical superoxide, with which it reacts to form peroxynitrite, a highly reactive agent that mediates some of the biological effects of NO (Beckman et al. 1990; Pacher et al. 2007). There are many sources of superoxide including cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, xanthine oxidase and mitochondrial enzymes (Adibhatla & Hatcher, 2009). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase is another enzyme that has recently emerged as a major source of superoxide in cerebral blood vessels and brain parenchyma (Chrissobolis & Faraci, 2008; Sorce & Krause, 2009). NADPH oxidase, a multi-unit enzyme first described in neutrophils (Bedard & Krause, 2007) is involved in the superoxide production evoked by a wide variety of agonists, ranging from inflammatory mediators, to β-amyloid and angiotensin II (Iadecola et al. 2009). As discussed in the next sections, the reaction of NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide with NO plays a key role in delayed preconditioning.

Cytoprotective effects of NO

The cytoprotective effects of NO typically occur through direct post-translational modification of proteins (S-nitrosylation), through activation of the cGMP second messenger system and through reaction with superoxide to form peroxynitrite (Table 1). S-Nitrosylation, produced by the direct reaction of NO with cysteine thiol groups, has been linked to neuroprotection through inhibition of NMDA receceptor activity (Lei et al. 1992; Lipton et al. 1993; Kim et al. 1999). In addition, S-nitrosylation may confer neuroprotection by inhibition of apoptosis, particularly through inactivation of caspases, proteases that degrade key intracellular proteins (Melino et al. 1997; Budihardjo et al. 1999; Zhou et al. 2005). S-Nitrosylation also leads to activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathway (Yun et al. 1998), which triggers the expression of prosurvival genes in cortical neurons. S-Nitrosylation can also play a role in gene expression through modification of transcription factors involved in neuronal survival, such as CREB (cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding; Lonze & Ginty, 2002). Recently, a study in cortical neurons found that the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), well known for its role in cell survival, induced CREB binding to target DNA (Riccio et al. 2006). These effects of NO on CREB-DNA binding are mediated by S-nitrosylation of histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) (Riccio et al. 2006). In addition, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a neuroprotective redox-sensitive transcription factor linked to antioxidant defences (Shih et al. 2005), is activated by S-nitrosylation of its cytoplasmic inhibitor KEAP1 (kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; Li et al. 2009). The resulting conformational changes lead to the dissociation of Nrf2/KEAP1 complexes and nuclear translocation of Nrf2, which, in turn, induces the transcription of antioxidant genes including glutathione reductase, peroxiredoxin, thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase, haemoxygenase-1, catalase, and extracellular superoxide dismutase, among others (Calabrese et al. 2009). In addition, S-nitrosylation of the p50 subunit negatively regulates the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB (nuclear factor κ lightchain enhancer of activated B cells), possibly contributing to an anti-inflammatory environment (Colasanti & Persichini, 2000).

Table 1.

Cytoprotective effects of NO

| Cellular effect | Possible protective mechanisms | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| S-Nitrosylation | ||

| Inhibits NR2A-containing NMDAR | Modifies channel properties, reduces Ca2+ influx and mitigates neurotoxicity | Lipton et al. 1993; Choi et al. 2000 |

| Inhibits caspase-3 activity | Reduces apoptosis and apoptotic morphological features | Melino et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 2005 |

| Dissociates HDAC2 from CREB-related promoters | BDNF increases CREB-DNA binding and CRE-dependent expression of neuroprotective genes | Riccio et al. 2006; Nott et al. 2008 |

| Dissociates Nrf2/KEAP complexes | Nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and transcription of antioxidant genes | Calabrese et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009 |

| Activates p21Ras | Activates the ERK signalling pathway, which plays a role in neuronal survival | Yun et al. 1998 |

| cGMP/PKG | ||

| CREB phosphorylation, Bcl-2 expression and activation of prosurvival Akt-GSK3 pathway | Growth factor expression and inhibition of apoptosis leading to survival of cerebellar granule neurons | Ciani et al. 2002a, 2002b |

| Contributes to ERK signalling and the expression of BDNF in cortical neurons | May provide trophic support to neurons | Gallo & Iadecola, 2011 |

| Activates mitoKATP channels in cardiomyocytes following ischaemic injury | Possible inhibition of mitochondrial transition pore | Ockaili et al. 1999; Qin et al. 2004; Costa & Garlid, 2008 |

| Improves synaptic function and amyloid-β accumulation in AD mouse model | Possible CREB activation | Puzzo et al. 2009 |

| Phosphorylation of the proapoptotic protein Bad at key functional residue | Inhibits apoptosis by binding to Bcl-xL | Johlfs & Fiscus, 2010 |

| Activation of Kv1.1/1.2 channels; increased GABA release probability | Increased GABAergic transmission may reduce cell death | Li et al. 2004; Dave et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2007 |

| Peroxynitrite | ||

| Protects from ischaemia–reperfusion injury in cardiac ischaemia | May inhibit neutrophil–endothelium interactions | Lefer et al. 1997 |

| Nitration or oxidation of tyrosine residues on proteins | May lead to activation of key neuroprotective pathways, such as ERK or Akt | Jope et al. 2000; Pesse et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006 |

HDAC2: histone deacetylase 2; CREB: cAMP responsive element-binding protein; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; KEAP1: Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; AD: Alzheimer's disease; Bcl: B-cell lymphoma.

A main biological target of NO is the haem-containing enzyme soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), which catalyses the conversion of GTP to cGMP. Numerous studies suggest that NO-dependent elevations in cGMP and consequent activation of protein kinase G (PKG) inhibit cell death and activate prosurvival pathways (Table 1). A role for NO in the expression of specific neuroplasticity-associated proteins, including BDNF, was recently demonstrated in cortical neurons and in the whisker barrel cortex, an effect that involves cGMP/PKG and ERK signalling (Gallo & Iadecola, 2011). Similarly, cGMP improves synaptic function and CREB activation in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (Puzzo et al. 2009). A glimpse into the cellular mechanisms of NO protection downstream of PKG is provided by studies in cardiomyocytes. Following ischaemia–reperfusion, NO-dependent PKG activity leads to activation of protein kinase Cɛ, which phosphorylates mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ (mitoKATP) channels (Costa & Garlid, 2008). The subsequent opening of the channels results in cytoprotection by inhibiting the mitochondrial transition pore (Costa & Garlid, 2008). Opening of mitoKATP channels is also associated with neuroprotection through mechanisms related to stabilization of mitochondrial function and prevention of apoptosis (Liu et al. 2002; Mayanagi et al. 2006).

NO rapidly reacts with superoxide to form peroxynitrite (Beckman et al. 1990). Besides its well-established toxic potential at high concentrations (Calabrese et al. 2009), at low concentrations peroxynitrite can act as a signalling molecule (Liaudet et al. 2009). For instance, in the vasculature, peroxynitrite is able to induce vascular relaxation and inhibition of platelet aggregation (Liu et al. 1994; Moro et al. 1994). Peroxynitrite protects cardiomyocytes from ischaemia–reperfusion injury (Lefer et al. 1997), an effect associated with inhibition of leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells (Table 1). In addition, peroxynitrite leads to redox modulation of proteins within signalling cascades that mediate neuroprotection (Liaudet et al. 2009). For example, peroxynitrite activates ERK and Akt signalling in different cells promoting their survival (Jope et al. 2000; Pesse et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006).

These observations suggest that NO has powerful protective effects that involve not only pro-survival signalling pathways, but also blood flow and vascular inflammatory events that play a prominent role in ischaemic brain injury. As discussed below, these aspects of NO biology are critical for understanding the protective effect that NO exerts in the context of ischaemic preconditioning.

Role of NO in early preconditioning

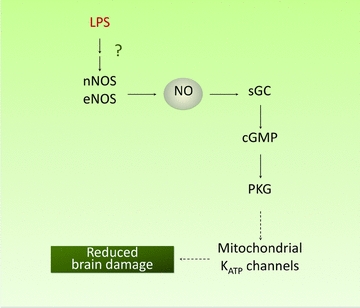

As illustrated in Table 2, NO has been implicated both in early and late preconditioning, and in the newborn as well in the adult brain. NO derived from eNOS and nNOS is essential for induction of tolerance in models of early preconditioning. For example, the lesion produced by neocortical injection of the glutamate receptor agonist NMDA was markedly reduced 1 h after administration of the pro-inflammatory mediator LPS in mice (Orio et al. 2007). The effect was not abolished by the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin, attesting to the fact that the protection did not require new protein synthesis, a hallmark of early preconditioning. The protection conferred by LPS was abolished by inhibitors of nNOS, and could be reconstituted by neocortical injection of a NO donor. Furthermore, the tolerance was not observed in nNOS or eNOS null mice, but was preserved in iNOS null mice and in mice treated with the iNOS inhibitor aminoguanidine (AG) (Orio et al. 2007). In agreement with LPS preconditioning in NMDA lesions, the early tolerance to focal ischaemic injury produced by a transient episode of focal cerebral ischaemia was not observed in eNOS or nNOS null mice (Atochin et al. 2003), suggesting that eNOS and nNOS-derived NO is also involved in other preconditioning and injury modalities. These observations implicate eNOS and nNOS, but not iNOS, as sources of NO. There is evidence that the mechanisms by which NO induces early tolerance involve the second messenger cGMP. Thus, the early tolerance conferred by LPS is abolished by the sGC inhibitor 1H-[1,2,4] oxadiazolo [4,3-a] quinoxalin-1-one and is re-established by exogenous cGMP (Orio et al. 2007). As discussed in the section ‘Cytoprotective effects of NO’ above, the mechanisms by which cGMP leads to tissue protection may involve PKG and mitoKATP channels. These observations, collectively, indicate that NO is critical for the establishment of ischaemic tolerance induced by transient ischaemia or by the proinflammatory mediator LPS, an effect involving activation of sGC and cGMP production (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Selected in vivo studies on the involvement of NO in ischaemic tolerance

| Species | PC stimulus | Type of PC | Injury model | Presumed source of NO | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | tMCAO | Early (0.5 h) | pMCAO | eNOS | Atochin et al. 2003 |

| nNOS | |||||

| Mouse | LPS | Early (1 h) | NMDA lesion | eNOS | Orio et al. 2007 |

| nNOS | |||||

| Rat, neonatal | Hypoxia | Late (24 h) | pCCAO and hypoxia | eNOS | Gidday, 2006 |

| Rat, neonatal | Isoflurane | Late (24 h) | pCCAO and hypoxia | iNOS | Zhao et al. 2007 |

| Rat, neonatal | LPS | Late (24 h) | pCCAO and hypoxia | eNOS | Lin et al. 2010 |

| Rat neonatal | Prenatal hypoxia | Late (48 h) | pCCAO and hypoxia | iNOS | Zhao & Zuo, 2005 |

| Rat | Isoflurane | Late (6–24 h) | tBCCAO and pMCAO | iNOS | Kapinya et al. 2002 |

| Mouse | tBCCAO or LPS | Late (24 h) | tMCAO | iNOS | Cho et al. 2005 |

| Mouse | tBCCAO or LPS | Late (24 h) | NMDA lesion | iNOS | Kawano et al. 2007 |

| Mouse | LPS | Late (24 h) | tMCAO | iNOS | Kunz et al. 2007 |

| Rat | Isoflurane | Late (24 h) | pMCAO | iNOS | Chi et al. 2010 |

| Mouse | Hypoxia | Late (24 h) | Subarachnoid haemorrhage | eNOS | Vellimana et al. 2011 |

| Rat | tMCAO | Late (36 h) | tMCAO | iNOS | Wen & Chen, 2007 |

| Mouse | tBCCAO | Late (48 h) | pMCAO | iNOS | Pradillo et al. 2009 |

| Rat | LPS | Late (72 h) | tMCAO | n.d. | Puisieux et al. 2000 |

| Rat | t4VO | Late (72 h) | t4VO | n.d. | Liu et al. 2006 |

| Gerbil | tBCCAO | Late (72 h) | tBCCAO | eNOS | Hashiguchi et al. 2004 |

| Rat | CSD | Late (96 h) | tMCAO | n.d. | Horiguchi et al. 2005 |

4VO: four vessel occlusion; BCCAO: bilateral common carotid artery occlusion; CCAO: common carotid artery occlusion (unilateral); CSD: cortical spreading depression; MCAO: middle cerebral artery occlusion; PC, preconditioning; tMCAO: transient MCAO; pMCAO: permanent MCAO; n.d.: not determined.

Figure 1. Nitric oxide in LPS-induced early preconditioning.

The pro-inflammatory mediator lipopolysaccharide (LPS) rapidly triggers a protein-synthesis-independent form of brain preconditioning, which is mediated by eNOS and nNOS-derived NO production and cGMP. The neuroprotective effect may involve activation of the cGMP effector kinase PKG and the consequent opening of mitochondrial KATP channels. Dashed lines refer to pathways which have not been elucidated.

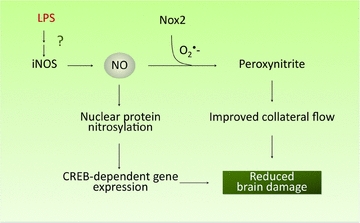

Role of NO in delayed preconditioning

Mounting evidence suggests that NO is also involved in delayed preconditioning. In hypoxic preconditioning in a neonatal rat model of ischaemic–hypoxic damage, the protection is abolished by the non-selective NOS inhibitor nitro-l-arginine, but not by the nNOS inhibitor 7-nitroindazole or the iNOS inhibitor AG (Table 2), implicating eNOS as the source of NO. Similar results were obtained in another model of preconditioning in neonatal rats (Lin et al. 2010). With some exceptions (Hashiguchi et al. 2004; Vellimana et al. 2011), the majority of studies on the role of NO in delayed preconditioning in the adult have indicated that the source of NO is iNOS (Table 2). Studies in adult mice have revealed a key role of iNOS in the preconditioning produced by LPS or transient forebrain ischaemia. iNOS null mice do not develop tolerance to focal ischaemia or NMDA lesions after treatment with LPS or transient forebrain ischaemia (Cho et al. 2005; Kawano et al. 2007; Kunz et al. 2007). Similarly, AG prevents the development of tolerance in these models. The preconditioning is associated with an increase in mitochondrial resistance to calcium-mediated depolarization (Cho et al. 2005), supporting the involvement of mitochondria also in the mechanisms of delayed tolerance (see Table 1 and section ‘Cytoprotective effects of NO’ above).

There is increasing evidence that preconditioning stimuli, in addition to changes in gene expression and mitochondrial function, also improve cerebrovascular function (Gidday, 2006). Therefore, the mechanisms of ischaemic tolerance may also include vascular effects that lead to an improvement of cerebral perfusion and blood–brain barrier function. In support of this possibility, LPS or ischaemic preconditioning improves cerebral blood flow and microvascular perfusion in vulnerable regions at the periphery of the ischaemic territory (ischaemic penumbra) (Dawson et al. 1999; Furuya et al. 2005; Hoyte et al. 2006; Zhao & Nowak, 2006; Kunz et al. 2007). After cerebral ischaemia, the mechanisms regulating cerebral circulation, such as the ability of neurons and endothelial cells to increase cerebral blood flow (CBF), are markedly impaired (Kunz & Iadecola, 2009). Such impairment may compromise the ability of cerebral blood vessels to compensate for the reduction in CBF in the ischaemic area by redistributing flow from adjacent vascular territories that are normally perfused (collateral circulation) (Kunz & Iadecola, 2009). We found that LPS preconditioning ameliorates the neurovascular alterations associated with focal cerebral ischaemia and increases CBF in regions of the ischaemic territory that are spared from infarction (Kunz et al. 2007). Such restoration of cerebrovascular function is not observed in mice treated with AG or in iNOS null mice, implicating iNOS in the mechanisms of the protection. Administration of preconditioning doses of LPS also increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), an effect mediated by NADPH oxidase (Nox2) (Kunz et al. 2007). This observation raises the possibility that the ROS superoxide reacts with NO to form peroxynitrite, which, in turn, mediates the preconditioning effects of NO. The following observations support this hypothesis. First, Nox2-null mice are not susceptible to LPS preconditioning, attesting to the need for superoxide to induce tolerance. Second, the peroxynitrite marker 3-nitrotyrosine is upregulated in the brain parenchyma and blood vessels by LPS preconditioning, an effect that is dependent on iNOS and Nox2. Third, the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTTPS (5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)prophyrinato iron (III)) blocks the beneficial vascular effects of LPS and counteracts, in part, the beneficial effects of LPS preconditioning on ischaemic injury (Kunz et al. 2007). Ischaemic preconditioning induced iNOS expression and accumulation of 3-nitrotyrosine in cerebral blood vessels (Cho et al. 2005), whereas LPS preconditioning was associated with accumulation of 3-nitrotyrosine in neurons and vessels (Kunz et al. 2007). Therefore, both vascular and neuronal sources could be involved in LPS preconditioning, whereas vascular sources may predominate in preconditioning induced by cerebral ischaemia.

In a model of brain injury produced by neocortical injection of NMDA (Kawano et al. 2007), the tolerance induced by LPS was not observed in iNOS null mice, but was present in cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-null mice, ruling out a role of COX-2 in the mechanisms of preconditioning. A NO donor was able to re-establish LPS tolerance in mice in which iNOS was inhibited by AG or in iNOS null mice, indicating that NO is an absolute requirement for the tolerance. Unlike early tolerance, a cGMP analogue was unable to re-establish the protection conferred by LPS preconditioning. Rather, the delayed tolerance was associated with increased 3-nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity, which was not observed in iNOS or Nox2-null mice supporting a role for peroxynitrite (Kawano et al. 2007). Accordingly, the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTTPS abolished the preconditioning effect of LPS. Therefore, peroxynitrite is involved both in the tolerance to ischaemic lesions and excitotoxicity.

These observations, collectively, suggest that LPS preconditioning induces iNOS-derived NO, which reacts with Nox2-derived superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which, in turn, is responsible for the protection (Fig. 2). The mechanisms by which peroxynitrite mediates the tissue protection remain to be elucidated, but may involve both cytoprotective and vasoprotective effects of low doses of peroxynitrite (Table 1). As discussed in section ‘Cytoprotective effects of NO’ above, NO could also be protective by additional mechanisms involving nitrosylation of nuclear proteins leading to activation of CREB-dependent transcription and expression of protective proteins (Table 1).

Figure 2. Nitric oxide in LPS-induced delayed preconditioning.

NO production via the activation of iNOS by LPS results in reduced brain damage most likely through a combination of cytoprotective and vasoprotective effects. Peroxynitrite, a product of the reaction of NO with superoxide (O2·−) derived from Nox2, may lead to increased cerebral blood flow to vulnerable regions near the ischaemic territory. NO may also activate prosurvival programmes, such as the expression of CREB-dependent genes, through S-nitrosylation.

Clinical implications

The findings reviewed above highlight the essential role of NO in the tolerance induced by ischaemia or the proinflammatory mediator LPS, strongly supporting the concept that NO serves as a key inducer of preconditioning. Therefore, NO could be of clinical value in patients at high risk of ischaemic stroke. Because NO can also be damaging in cerebral ischaemia, its beneficial effects in preconditioning need to be weighed against potential deleterious effects on the ischaemic tissue. The actions of NO on the ischaemic brain are time and context dependent (Iadecola, 1997). NO is protective in the early phase after induction of ischaemia, when modulation of CBF ameliorates tissue damage, and destructive in the late phase, when the deleterious effects of NO on mitochondrial enzymes and DNA worsen the metabolic state of the tissue (Iadecola, 1997). Our data in NMDA lesions suggest that administration of NO donors 20 h prior to the ischaemic insult is beneficial (Kawano et al. 2007), but it remains unclear whether a similar timing will be effective in focal ischaemia. Furthermore, NO donors were administered after LPS, indicating that other factors induced by LPS, such as free radicals, are required to enable the preconditioning potential of NO. Studies addressing these issues would be a welcome addition to the field. The hypotensive effects of systemic administration of NO donors may be a complicating factor that also needs to be considered. Targeting NO delivery to the specific tissue and cellular compartments remains a challenge for all NO-based therapies. Perhaps, pharmacological activation of protective downstream pathways linked to NO preconditioning (Table 1) may overcome some of these difficulties. Despite these challenges, the realization that NO has a critical role in preconditioning opens new avenues in the prevention of ischaemic stroke in high risk patients, while providing valuable clues to brain protection in acute stroke.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants NS34179 (C.I., J.A.), NS35806 (C.I., J.A.) and AG35067 (E.F.G.), and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft KA 2279/4-1(T.K.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AG

aminoguanidine

- BDNF

brain derived neurotrophic factor

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- CREB

cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ERK

extracellular-signal-regulated kinase

- FeTTPS

5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)prophyrinato iron (III)

- HDAC2

histone deacetylase 2

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KEAP1

kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

- Nox2

NADPH oxidase 2

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- PKG

protein kinase G

- sGC

soluble guanylyl cyclase

References

- Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Lipid oxidation and peroxidation in CNS health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;12:125–169. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357:593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atochin DN, Clark J, Demchenko IT, Moskowitz MA, Huang PL. Rapid cerebral ischemic preconditioning in mice deficient in endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthases. Stroke. 2003;34:1299–1303. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000066870.70976.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budihardjo I, Oliver H, Lutter M, Luo X, Wang X. Biochemical pathways of caspase activation during apoptosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:269–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Rizzarelli E, Owen JB, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Butterfield DA. Nitric oxide in cell survival: a janus molecule. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2717–2739. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi OZ, Hunter C, Liu X, Weiss HR. The effects of isoflurane pretreatment on cerebral blood flow, capillary permeability, and oxygen consumption in focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1412–1418. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d6c0ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Park EM, Zhou P, Frys K, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Obligatory role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in ischemic preconditioning. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:493–501. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YB, Tenneti L, Le DA, Ortiz J, Bai G, Chen HSV, Lipton SA. Molecular basis of NMDA receptor-coupled ion channel modulation by S-nitrosylation. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:15–21. doi: 10.1038/71090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrissobolis S, Faraci FM. The role of oxidative stress and NADPH oxidase in cerebrovascular disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani E, Guidi S, Bartesaghi R, Contestabile A. Nitric oxide regulates cGMP-dependent cAMP-responsive element binding protein phosphorylation and Bcl-2 expression in cerebellar neurons: implication for a survival role of nitric oxide. J Neurochem. 2002a;82:1282–1289. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani E, Virgili M, Contestabile A. Akt pathway mediates a cGMP-dependent survival role of nitric oxide in cerebellar granule neurones. J Neurochem. 2002b;81:218–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti M, Persichini T. Nitric oxide: an inhibitor of NF-κB/Rel system in glial cells. Brain Res Bull. 2000;52:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa ADT, Garlid KD. Intramitochondrial signaling: interactions among mitoKATP, PKCɛ, ROS, and MPT. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H874–H882. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01189.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl N, Balfour W. Prolonged anoxic survival due to anoxia pre-exposure: brain ATP, lactate, and pyruvate. Am J Physiol. 1964;207:452–456. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.207.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave KR, Lange-Asschenfeldt C, Raval AP, Prado R, Busto R, Saul I, Pérez-Pinzón MA. Ischemic preconditioning ameliorates excitotoxicity by shifting glutamate/γ-aminobutyric acid release and biosynthesis. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:665–673. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Furuya K, Gotoh J, Nakao Y, Hallenbeck JM. Cerebrovascular hemodynamics and ischemic tolerance: lipopolysaccharide-induced resistance to focal cerebral ischemia is not due to changes in severity of the initial ischemic insult, but is associated with preservation of microvascular perfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:616–623. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, Becker K, Meisel A. Preconditioning and tolerance against cerebral ischaemia: from experimental strategies to clinical use. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:398–412. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya K, Zhu L, Kawahara N, Abe O, Kirino T. Differences in infarct evolution between lipopolysaccharide-induced tolerant and nontolerant conditions to focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:715–723. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.4.0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo EF, Iadecola C. Neuronal nitric oxide contributes to neuroplasticity-associated protein expression through cGMP, protein kinase G, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6947–6955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0374-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidday JM. Cerebral preconditioning and ischaemic tolerance. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:437–448. doi: 10.1038/nrn1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross SS, Wolin MS. Nitric oxide: pathophysiological mechanisms. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:737–769. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiguchi A, Yano S, Morioka M, Hamada J, Ushio Y, Takeuchi Y, Fukunaga K. Up-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway contributes to ischemic tolerance in the CA1 subfield of gerbil hippocampus. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:271–279. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000110539.96047.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi T, Snipes JA, Kis B, Shimizu K, Busija DW. The role of nitric oxide in the development of cortical spreading depression-induced tolerance to transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2005;1039:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyte LC, Papadakis M, Barber PA, Buchan AM. Improved regional cerebral blood flow is important for the protection seen in a mouse model of late phase ischemic preconditioning. Brain Res. 2006;1121:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. Bright and dark sides of nitric oxide in ischemic brain injury. Trends in Neurosci. 1997;20:132–139. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Park L, Capone C. Threats to the mind: aging, amyloid, and hypertension. Stroke. 2009;40:S40–S44. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.533638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johlfs MG, Fiscus RR. Protein kinase G type-Iα phosphorylates the apoptosis-regulating protein Bad at serine 155 and protects against apoptosis in N1E-115 cells. Neurochem Int. 2010;56:546–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jope RS, Zhang L, Song L. Peroxynitrite modulates the activation of p38 and extracellular regulated kinases in PC12 cells. Arch Biochem and Biophys. 2000;376:365–370. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapinya KJ, Lowl D, Futterer C, Maurer M, Waschke KF, Isaev NK, Dirnagl U. Tolerance against ischemic neuronal injury can be induced by volatile anesthetics and is inducible NO synthase dependent. Stroke. 2002;33:1889–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020092.41820.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Kunz A, Abe T, Girouard H, Anrather J, Zhou P, Iadecola C. iNOS-derived NO and nox2-derived superoxide confer tolerance to excitotoxic brain injury through peroxynitrite. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1453–1462. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WK, Choi YB, Rayudu PV, Das P, Asaad W, Arnelle DR, Stamler JS, Lipton SA. Attenuation of NMDA receptor activity and neurotoxicity by nitroxyl anion, NO−. Neuron. 1999;24:461–469. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80859-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa K, Matsumoto M, Tagaya M, Hata R, Ueda H, Niinobe M, Handa N, Fukunaga R, Kimura K, Mikoshiba K. ‘Ischemic tolerance’ phenomenon found in the brain. Brain Res. 1990;528:21–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90189-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz A, Iadecola C. Cerebral vascular dysregulation in the ischemic brain. Handb Clin Neurol. 2009;92:283–305. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(08)01914-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz A, Park L, Abe T, Gallo EF, Anrather J, Zhou P, Iadecola C. Neurovascular protection by ischemic tolerance: Role of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7083–7093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1645-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefer DJ, Scalia R, Campbell B, Nossuli T, Hayward R, Salamon M, Grayson J, Lefer AM. Peroxynitrite inhibits leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:684–691. doi: 10.1172/JCI119212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei SZ, Pan ZH, Aggarwal SK, Chen HSV, Hartman J, Sucher NJ, Lipton SA. Effect of nitric oxide production on the redox modulatory site of the NMDA receptor-channel complex. Neuron. 1992;8:1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CQ, Kim MY, Godoy LC, Thiantanawat A, Trudel LJ, Wogan GN. Nitric oxide activation of Keap1/Nrf2 signaling in human colon carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14547–14551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907539106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DP, Chen SR, Finnegan TF, Pan HL. Signalling pathway of nitric oxide in synaptic GABA release in the rat paraventricular nucleus. J Physiol. 2004;554:100–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MH, Cha YN, Surh YJ. Peroxynitrite induces HO-1 expression via PI3K/Akt-dependent activation of NF-E2-related factor 2 in PC12 cells. Free Radic Biol and Med. 2006;41:1079–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaudet L, Vassalli G, Pacher P. Role of peroxynitrite in the redox regulation of cell signal transduction pathways. Front Biosci. 2009;14:4809–4814. doi: 10.2741/3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HY, Wu CL, Huang CC. The Akt-endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway in lipopolysaccharide preconditioning-induced hypoxic-ischemic tolerance in the neonatal rat brain. Stroke. 2010;41:1543–1551. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.574004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA, Choi YB, Pan ZH, Lei SZ, Chen HSV, Sucher NJ, Loscalzo J, Singel DJ, Stamler JS. A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compounds. Nature. 1993;364:626–632. doi: 10.1038/364626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Lu C, Wan R, Auyeung WW, Mattson MP. Activation of mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channels protects neurons against ischemia-induced death by a mechanism involving suppression of Bax translocation and cytochrome c release. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:431–443. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HQ, Li WB, Li QJ, Zhang M, Sun XC, Feng RF, Xian XH, Li SQ, Qi J, Zhao HG. Nitric oxide participates in the induction of brain ischemic tolerance via activating ERK1/2 signaling pathways. Neurochem Res. 2006;31:967–974. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Beckman JS, Ku DD. Peroxynitrite, a product of superoxide and nitric oxide, produces coronary vasorelaxation in dogs. J Pharm and Exp Therap. 1994;268:1114–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze BE, Ginty DD. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35:605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayanagi K, Gáspár T, Katakam PVG, Kis B, Busija DW. The mitochondrial KATP channel opener BMS-191095 reduces neuronal damage after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;27:348–355. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melino G, Bernassola F, Knight RA, Corasaniti MT, Nistic G, Finazzi-Agr A. S-nitrosylation regulates apoptosis. Nature. 1997;388:432–433. doi: 10.1038/41237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro MA, Darley-Usmar VM, Goodwin DA, Read NG, Zamora-Pino R, Feelisch M, Radomski MW, Moncada S. Paradoxical fate and biological action of peroxynitrite on human platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6702–6706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche F. Twilight of the Idols. 2007. Wordsworth Editions Ltd.

- Nott A, Watson PM, Robinson JD, Crepaldi L, Riccio A. S-nitrosylation of histone deacetylase 2 induces chromatin remodelling in neurons. Nature. 2008;455:411–415. doi: 10.1038/nature07238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockaili R, Emani VR, Okubo S, Brown M, Krottapalli K, Kukreja RC. Opening of mitochondrial KATP channel induces early and delayed cardioprotective effect: role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;277:H2425–H2434. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.6.H2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio M, Kunz A, Kawano T, Anrather J, Zhou P, Iadecola C. Lipopolysaccharide induces early tolerance to excitotoxicity via nitric oxide and cGMP. Stroke. 2007;38:2812–2817. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinzon MA, Dave KR, Raval AP. Role of reactive oxygen species and protein kinase C in ischemic tolerance in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1150–1157. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesse B, Levrand S, Feihl F, Waeber B, Gavillet B, Pacher P, Liaudet L. Peroxynitrite activates ERK via Raf-1 and MEK, independently from EGF receptor and p21Ras in H9C2 cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:765–775. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradillo JM, Fernandez-Lopez D, Garcia-Yebenes I, Sobrado M, Hurtado O, Moro MA, Lizasoain I. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in neuroprotection afforded by ischemic preconditioning. J Neurochem. 2009;109:287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puisieux F, Deplanque D, Pu Q, Souil E, Bastide M, Bordet R. Differential role of nitric oxide pathway and heat shock protein in preconditioning and lipopolysaccharide-induced brain ischemic tolerance. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;389:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00893-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzzo D, Staniszewski A, Deng SX, Privitera L, Leznik E, Liu S, Zhang H, Feng Y, Palmeri A, Landry DW, Arancio O. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibition improves synaptic function, memory, and amyloid-β load in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8075–8086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0864-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Yang XM, Cui L, Critz SD, Cohen MV, Browner NC, Lincoln TM, Downey JM. Exogenous NO triggers preconditioning via a cGMP- and mitoKATP-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H712–H718. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00954.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis DJ, Kobylarz K, Yamamoto S, Golanov EV. Brief electrical stimulation of cerebellar fastigial nucleus conditions long-lasting salvage from focal cerebral ischemia: conditioned central neurogenic neuroprotection. Brain Res. 1998;780:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A, Alvania RS, Lonze BE, Ramanan N, Kim T, Huang Y, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Ginty DD. A nitric oxide signaling pathway controls CREB-mediated gene expression in neurons. Mol Cell. 2006;21:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih AY, Li P, Murphy TH. A small-molecule-inducible Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response provides effective prophylaxis against cerebral ischemia in vivo. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10321–10335. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4014-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorce S, Krause KH. NOX enzymes in the central nervous system: from signaling to disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2481–2504. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagliano NE, Perez-Pinzon MA, Moskowitz MA, Huang PL. Focal ischemic preconditioning induces rapid tolerance to middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:757–761. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199907000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS, Simon DI, Osborne JA, Mullins ME, Jaraki O, Michel T, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. S-Nitrosylation of proteins with nitric oxide: synthesis and characterization of biologically active compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:444–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel-Poore MP, Stevens SL, King JS, Simon RP. Preconditioning reprograms the response to ischemic injury and primes the emergence of unique endogenous neuroprotective phenotypes: a speculative synthesis. Stroke. 2007;38:680–685. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251444.56487.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel-Poore MP, Stevens SL, Xiong Z, Lessov NS, Harrington CA, Mori M, Meller R, Rosenzweig HL, Tobar E, Shaw TE, Chu X, Simon RP. Effect of ischaemic preconditioning on genomic response to cerebral ischaemia: similarity to neuroprotective strategies in hibernation and hypoxia-tolerant states. Lancet. 2003;362:1028–1037. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe AM, Altay T, Freie AB, Gidday JM. Repetitive hypoxia extends endogenous neurovascular protection for stroke. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:975–985. doi: 10.1002/ana.22367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellimana AK, Milner E, Azad TD, Harries MD, Zhou ML, Gidday JM, Han BH, Zipfel GJ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase mediates endogenous protection against subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced cerebral vasospasm. Stroke. 2011;42:776–782. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen JY, Chen ZW. Protective effect of pharmacological preconditioning of total flavones of Abelmoschl manihot on cerebral ischemic reperfusion injury in rats. Am J Chin Med. 2007;35:653–661. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X07005144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Chen SR, Li DP, Pan HL. Kv1.1/1.2 channels are downstream effectors of nitric oxide on synaptic GABA release to preautonomic neurons in the paraventricular nucleus. Neuroscience. 2007;149:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun HY, Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Nitric oxide mediates N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-induced activation of p21ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5773–5778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Nowak TS., Jr CBF changes associated with focal ischemic preconditioning in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1128–1140. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Peng L, Li L, Xu X, Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning improves long-term neurologic outcome after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:963–970. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000291447.21046.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Zuo Z. Prenatal hypoxia-induced adaptation and neuroprotection that is inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Qian L, Iadecola C. Nitric oxide inhibits caspase activation and apoptotic morphology but does not rescue neuronal death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:348–357. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]