Abstract

Background

Cultural biases may affect the individual responses to questionnaires for depression and thus confound the international or multiethnic researches on depression.

Objective

We compared the diagnostic accuracy of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) for major depressive disorder (MDD) in late life between Korean and US Caucasian elderly.

Methods

This study included 332 US Caucasian MDD patients, 116 Korean MDD patients, 125 US Caucasian nondepressed subjects and 700 Korean nondepressed subjects. Differential item functioning and factor analyses were conducted to examine the differences in the response patterns to the CES-D between the US Caucasian and Korean elderly. Diagnostic accuracy of the CES-D for MDD was compared using the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curves (AUC).

Results

The Korean elderly were more likely to endorse 6 items compared to the US Caucasians, and the US Caucasian elderly were more likely to endorse 5 items compared to the Koreans. The factor solutions from both ethnic groups were not comparable since the congruence coefficient for the second factor was below 0.46 and that for the first factor did not reach 0.90. The AUC of the CES-D for MDD in Koreans (AUC = 0.850, 95% CI = 0.801–0.899) was significantly smaller than that in US Caucasians (AUC = 0.973, 95% CI = 0.960–0.987), and the optimal cutoff score of the CES-D in the Korean elderly (21/22) was 2 times higher than that in the US Caucasian elderly (10/11).

Conclusion

Cross-cultural issues may significantly influence the diagnostic accuracy of depression questionnaires and thus should be considered more carefully than before in both clinical and research settings on multiethnic populations.

Key Words: Depression; Diagnostic accuracy, questionnaires; Koreans; Caucasians; Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Introduction

Depression is one of the most prevalent psychiatric conditions in late life [1]. It occurs 3 times as frequently in the elderly as in the rest of the population, and depressive symptoms affect about 30% of Asian and Caucasian people aged over 65 [2,3,4,5]. As aging of the population is accelerating remarkably in Asian countries including Korea [6], the number of people with depression is also on a steep rise. In late life, depression is often associated with functional decline, diminished quality of life, increased caregiver burden and service utilization, risk of hospitalization, mortality from comorbid medical conditions and suicide [7,8,9,10]. However, depression in late life, despite its prevalence and impact, remains underdiagnosed and inadequately treated for many reasons, such as subsyndromal presentations, coexisting medical illnesses, reluctance to self-report symptoms due to a fear of stigmatization and passivity, and limited expectations of treatments [11].

Therefore, active screening may be effective in improving case finding for depression in elderly people [12], and screening for depression can be facilitated by using brief questionnaires. Various self-reporting questionnaires for depression such as the Beck Depression Inventory [13], the Geriatric Depression Scale [14], the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [15], and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale [16] are widely used for screening depression in both clinical and research settings, not only in English-speaking countries but also in non-English-speaking countries. However, individual responses to these questions have been shown to be affected by cultural biases due to the effects of translation from English to other languages, patients’ different interpretations of its emotional terms, and various cultural factors, such as perceptions of racial prejudice and a cultural group's work ethic [17,18,19,20,21]. For example, Latinos were less likely to endorse inability to work than English speakers [22], and Koreans were less likely to endorse positive affect than Caucasian Americans [18]. In a recent qualitative content analysis of 30 studies that investigated the meaning of culture for the expression of depression, culture was found to shape the symptoms and expressions of depression and thus diagnostic scales developed in the western world may lead to misdiagnosis of depressive symptoms in several ethnic minorities [23].

On this account, the diagnostic accuracy of these questionnaires for depression may also be subject to cultural biases in elderly people, which may complicate international cooperative studies or cross-cultural comparison studies of geriatric depression. However, to date, no studies have directly examined cross-cultural differences in diagnostic accuracy of depression self-report questionnaires and its impact on the results of research and clinical practice in late-life depression. Therefore, in the present study, we compared the diagnostic accuracy of the CES-D for major depressive disorder (MDD) in late life between Korean and US Caucasian elderly.

Method

Subjects

This study included 332 US Caucasian MDD patients, 116 Korean MDD patients, 125 US Caucasian nondepressed subjects and 700 Korean nondepressed subjects. All the subjects were aged 55 years or more (age range = 58–95). Demographic characteristics of participants are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects

| Depressed patients |

Nondepressed subjects |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koreans | US Caucasians | Koreans | US Caucasians | |

| Age, years | 71.87±7.20∗,+ | 69.70±7.28+ | 75.01±8.07∗,+ | 69.96±5.63+ |

| Gender (women), % | 77.59∗' + | 64.16+ | 49.86∗,+ | 71.20+ |

| Education, years | 6.50±5.18∗,+ | 13.61±3.03∗,+ | 8.08±5.64∗,+ | 15.58±1.65∗,+ |

| CES-D, points | 30.84±14.36∗ | 30.48±12.70 | 11.93±8.58∗,+ | 1.98±2.98+ |

With the exception of gender the values represent mean ± SD.

p < 0.01 between nondepressed controls and depressed patients

p < 0.01 between US Caucasians and Koreans.

Nondepressed Korean elderly were enrolled from a cohort of community-dwelling Koreans who participated in the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLOSHA) [24]. Korean elderly with MDD were enrolled either from the KLOSHA or from patients receiving care at the Late Life Depression Clinic of the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH) from January 2007 to April 2009.

All US Caucasian subjects were enrolled in the National Institute of Mental Health-supported Conte Neuroscience Center at the Duke University Medical Center. Nondepressed US Caucasian elderly were obtained from a volunteer registry in the Duke Center for Aging. Older depressed US Caucasian adults were inpatients and outpatients referred by the psychiatry service and the general medical clinics at Duke.

All participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of SNUBH and Duke University Hospital.

Assessments

Korean subjects were administered the Korean version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [25] by research psychiatrists for diagnosing or ruling out MDD and other major psychiatric disorders. Subjects also completed the self-report Korean version of the CES-D [26,27] for evaluating depressive symptoms.

For US Caucasian subjects, a trained research assistant administered the Duke Depression Evaluation Schedule [28], a composite diagnostic instrument that includes basic sociodemographic questions as well as sections of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule modified for DSM-IV to establish MDD diagnosis [29]. Subjects also completed the English version of the CES-D [30]. Study psychiatrists interviewed patients and confirmed DSM-IV major depression diagnoses.

MDD was diagnosed according to the DSM-IV criteria, and minor depressive disorder according to the research criteria proposed in Appendix B of the DSM-IV criteria [29]. Other major psychiatric disorders including dementia were also diagnosed according to the DSM-IV criteria [29].

The MDD group consisted of subjects diagnosed with MDD without other comorbid psychiatric disorders in both the Korean and US Caucasian samples. Subjects who had no psychiatric disorders including minor depressive disorder were enrolled in the nondepressed group in both Korean and US Caucasian samples.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were compared between US Caucasians and Koreans using Student's t tests and χ2 tests. The total and item scores of the CES-D were compared between US Caucasians and Koreans within each diagnostic group using analysis of variance controlling age, gender, and educational level with the Bonferroni correction. In order to detect different response patterns between the US Caucasian and Korean elderly, a differential item functioning (DIF) [31] analysis was conducted using a partial correlation method. We computed the correlation between individual items and group membership (coded as US Caucasian = 0 and Korean = 1) while partialling out the age, gender, education, and total CES-D score. p < 0.0025 was considered statistically significant. The purpose of this latter analysis was to identify the patterns of the endorsement of individual items controlling for the overall levels of depression. A positive coefficient indicates that the item is overendorsed by Koreans, and a negative coefficient indicates that the item is overendorsed by US Caucasians.

Factor structures of the CES-D in US Caucasians and Koreans were computed using principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The extracted factor matrices were then compared between the groups. A congruence coefficient was calculated to quantify the overlap between factor matrices and determines the degree of similarity between them [32]. Congruence coefficients greater than 0.90 are conventionally suggested to be an indication of factor invariance, and those lower than 0.46 are regarded as an indication of factor incongruence [33,34].

The optimal cutoff scores satisfying both sensitivity and specificity for MDD were determined by the receiver-operating characteristic curve analyses. To measure the diagnostic accuracy of the CES-D for MDD in Koreans and US Caucasians, the area under the ROC curves (AUC), the standard errors, and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. The diagnostic accuracy of the CES-D for MDD between US Caucasians and Koreans was compared by comparing the AUC between the Korean sample and the US Caucasian sample.

All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0.

Results

In the nondepressed elderly group, the total CES-D scores of Koreans were about 6 times higher than those of US Caucasians (11.93 ± 8.58 vs. 1.98 ± 2.98, p < 0.001). However, in the MDD group, the total CES-D scores of Koreans were comparable to those of US Caucasians (30.84 ± 14.36 vs. 30.48 ± 12.70, p < 0.01, Student's t test).

In the nondepressed elderly group, Koreans showed higher scores than US Caucasians in all CES-D items, and the difference was statistically significant in 5 items: ‘I felt I was just as good as other people’ (1.64 ± 1.27 vs. 0.02 ± 0.27, p < 0.001), ‘I thought my life had been a failure’ (0.52 ± 0.90 vs. 0.02 ± 0.27, p = 0.002), ‘I was happy’ (1.79 ± 1.30 vs. 0.06 ± 0.40, p < 0.001), ‘I talked less than usual’ (0.49 ± 0.81 vs. 0.11 ± 0.39, p, 0.001), and ‘I enjoyed life’ (1.59 ± 1.34 vs. 0.04 ± 0.30, p < 0.001).

In contrast, in the MDD group, US Caucasians showed higher scores than Koreans in 5 items: ‘I felt depressed’ (2.32 ± 1.02 vs. 1.62 ± 1.21, p < 0.001), ‘I felt everything I did was an effort’ (2.19 ± 1.15 vs. 1.67 ± 1.15, p = 0.001), ‘I enjoyed life’ (1.66 ± 1.25 vs. 1.16 ± 0.87, p = 0.001), ‘I felt sad’ (2.23 ± 1.07 vs. 1.32 ± 1.01, p < 0.001), and ‘I could not get going’ (1.94 ± 1.22 vs. 1.63 ± 1.18, p = 0.001). In the MDD group, Koreans showed higher scores than US Caucasians only in two items: ‘I felt I was just as good as other people’ (1.73 ± 1.15 vs. 1.01 ± 1.32, p < 0.001) and ‘People were unfriendly’ (1.28 ± 1.12 vs. 0.36 ± 0.84, p < 0.001).

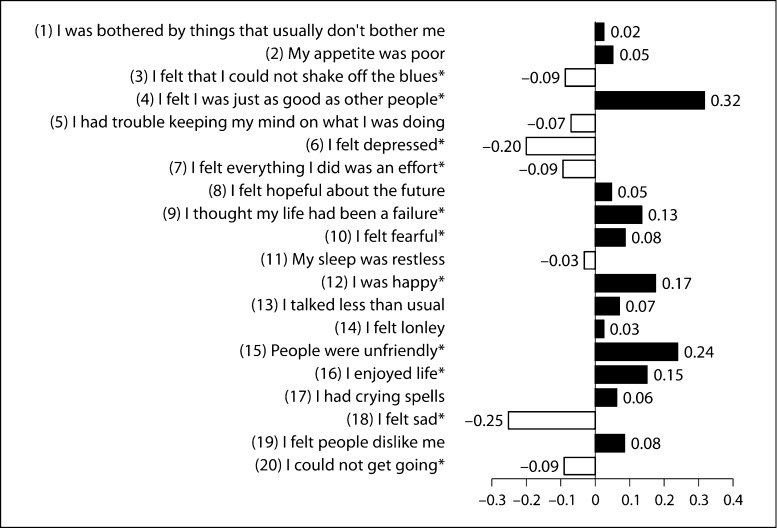

To detect a DIF after controlling overall levels of depression, we assessed correlation coefficients of individual items of the CES-D with group membership (US Caucasian = 0, Korean = 1) after partialling out the effects of age, gender, education, and the total CES-D score. Significant positive coefficients were found in 6 items (0.32 for ‘I felt I was just as good as other people’, 0.13 for ‘I thought my life had been a failure’, 0.08 for ‘I felt fearful’, 0.17 for ‘I was happy’, 0.24 for ‘People were unfriendly’, 0.15 for ‘I enjoyed life’) and significant negative coefficients were found in 5 items (–0.09 for ‘I felt that I could not shake off the blues’, –0.20 for ‘I felt depressed’, –0.09 for ‘I felt everything I did was an effort’, –0.25 for ‘I felt sad’, and –0.09 for ‘I could not get going’) (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of response patterns to the CES-D items between US Caucasian elderly and Korean elderly. ∗ p < 0.0025, by correlation tests partialling out the age, gender, education, and total CES-D score (US Caucasian was coded as 0 and Korean as 1).

Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was conducted separately for the Korean elderly and the US Caucasian elderly (table 2). In the Korean elderly, two factors were extracted, accounting for a total of 54.66% of the variance. We named these factors ‘negative affect’ and ‘positive affect,’ since the second factor only included the three positive affect items in the Korean version of the CES-D (‘I felt I was just as good as other people’, ‘I was happy’, ‘I enjoyed life’). In the US Caucasian elderly, two factors were also extracted explaining 53.49% of the variance. We named these factors ‘depressed mood’ and ‘negative interpersonal perception’, since the second factor included the 4 items related to subjective appraisal of interpersonal situations or comparison with others (‘I felt I was just as good as other people’, ‘I thought my life had been a failure’, ‘People were unfriendly’, ‘I felt people dislike me’). The comparison of factor structures for the CES-D between the Korean and US Caucasian elderly provided congruent coefficients of 0.861 for the first factor and 0.377 for the second factor, indicating that factor solutions of the Korean and US Caucasian elderly were considered to be not well replicated in the CES-D.

Table 2.

Comparison of the factor structures of the CES-D between US Caucasians and Koreans

| US Caucasians |

Koreans |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| factor 1 | factor 2 | factor 1 | factor 2 | ||

| 1 | I was bothered by things that usually don't bother me | 0.687 | 0.080 | 0.720 | −0.062 |

| 2 | My appetite was poor | 0.581 | 0.048 | 0.606 | 0.113 |

| 3 | I felt that I could not shake off the blues | 0.825 | 0.228 | 0.814 | 0.016 |

| 4 | I felt I was just as good as other people | 0.354 | 0.580 | 0.087 | 0.775 |

| 5 | I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing | 0.707 | 0.177 | 0.725 | 0.022 |

| 6 | I felt depressed | 0.855 | 0.217 | 0.818 | 0.022 |

| 7 | I felt everything I did was an effort | 0.803 | 0.213 | 0.759 | 0.005 |

| 8 | I felt hopeful about the future | 0.594 | 0.374 | 0.785 | −0.047 |

| 9 | I thought my life had been a failure | 0.403 | 0.465 | 0.700 | −0.029 |

| 10 | I felt fearful | 0.546 | 0.340 | 0.773 | −0.051 |

| 11 | My sleep was restless | 0.633 | 0.026 | 0.603 | 0.096 |

| 12 | I was happy | 0.790 | 0.284 | 0.010 | 0.804 |

| 13 | I talked less than usual | 0.548 | 0.258 | 0.651 | 0.068 |

| 14 | I felt lonely | 0.635 | 0.298 | 0.780 | 0.033 |

| 15 | People were unfriendly | 0.014 | 0.747 | 0.707 | −0.027 |

| 16 | I enjoyed life | 0.729 | 0.303 | −0.089 | 0.773 |

| 17 | I had crying spells | 0.513 | 0.101 | 0.743 | −0.021 |

| 18 | I felt sad | 0.840 | 0.222 | 0.791 | −0.064 |

| 19 | I felt people dislike me | 0.079 | 0.808 | 0.623 | −0.036 |

| 20 | I could not get going | 0.724 | 0.205 | 0.737 | −0.006 |

| Eigenvalue | 9.254 | 1.443 | 9.044 | 1.888 | |

| Variance explained, % | 40.32 | 13.17 | 45.22 | 9.44 | |

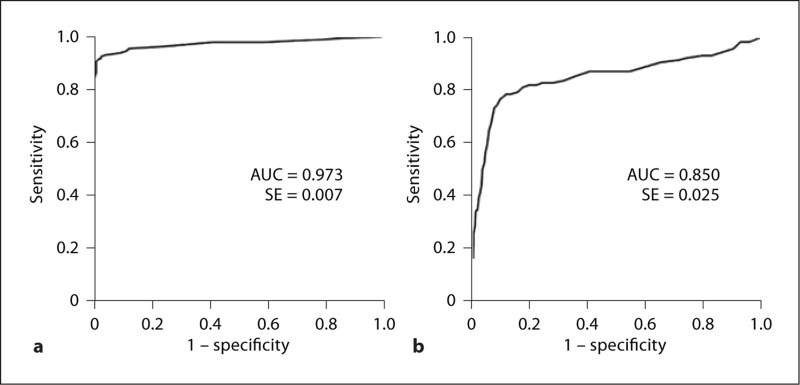

As shown in figure 2, the CES-D was found to be useful for detecting MDD in both US Caucasians and Koreans since the AUCs were larger than 0.8 and the 95% CIs of the AUCs did not incorporate 0.5. However, the AUC of the CES-D for MDD in Koreans was significantly smaller than that in US Caucasians (AUC = 0.850, 95% CI = 0.801–0.899 in Koreans; AUC = 0.973, 95% CI = 0.960–0.987 in Caucasians, z = –4.738, p < 0.001), indicating that the diagnostic accuracy of the CES-D may be significantly lower in Koreans compared with US Caucasians. The optimal cutoff score of the CES-D in the Korean elderly was determined as 21/22 (sensitivity = 0.784, specificity = 0.881), which was almost 2 times higher than that in the US Caucasian elderly (cutoff score = 10/11, sensitivity = 0.925, specificity = 0.976).

Fig. 2.

Receiver operator curve analyses of the CES-D for MDD in US Caucasian (a) and Korean (b) elderly. The AUC was significantly larger in US Caucasians than in Koreans (p < 0.001). SE = Standard error of AUC.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated differences in response to the CES-D between Koreans and US Caucasians for both depressed and nondepressed groups. Principal component analysis revealed clinically meaningful factors among groups. Finally, sensitivity analyses showed clear differences between the two ethnic groups, leading to markedly different optimal cutoff scores for the CES-D as a screen for MDD. These findings suggest that ethnocultural factors influence manifestation of depressive symptoms and thus the responses to depression questionnaires. Although factor analysis yielded two factors for both the Korean and US Caucasian samples, the factor solutions from both ethnic groups were not comparable since the congruence coefficient for the second factor was below 0.46 and that for the first factor did not reach 0.90.

Differences in the response style to the questions on mood between Koreans and US Caucasians had already been reported twice [18,19]. In these studies, Korean Americans were found to be more reluctant to endorse positive feelings than Caucasian Americans [18,19], and this tendency was significantly influenced by the level of their acculturation to western culture [18]. Consistent with these earlier observations, the DIF coefficients were positive in all three positive affect items in the present study, indicating that the Korean elderly endorsed statements related to positive affect much less than the US Caucasian elderly. This may be attributed to the cultural characteristics of modesty and self-effacement in Korea [35]. This reluctance to endorse positive affects is commonly observed in other Asian populations [36,37] and Hispanic populations [38]. Interestingly, their responses to item 8 (‘I felt hopeful about the future’) which was translated into a negative question in the Korean version of the CES-D (‘I felt hopeless about the future’) were not different between the two groups, suggesting that the way of asking mood should be adjusted to cultural norms to ensure cross-cultural equivalence. In addition to the three positive items, Koreans were more likely to endorse items 15 (‘People were unfriendly’) and 19 (‘I felt people dislike me’) than US Caucasians. This may be attributed to relatively high interpersonal relationship sensitivity of Koreans. Interpersonal perception is also affected by cultural norms. Individuals from a more hierarchically structured culture like Korea were known to be more sensitive to the status of people than Americans who at least nominally belong to a more egalitarian culture [39]. Finally, the Korean elderly were more likely to endorse item 9 (‘I thought my life had been a failure’) than the US Caucasian elderly. For the past few decades, Korea has gone through tremendous sociocultural, economic and political changes, and many Korean elderly have felt caught in the middle of these rapid changes. As a result, many older Koreans may have difficulty giving their lives a satisfactory appraisal in the success-oriented atmosphere of Korea. Therefore, the differences in the CES-D scores between Korean elderly and US Caucasian elderly may reflect not only true differences in mood but also differences in the mode of mood expression.

Although the CES-D was found be useful for detecting MDD in both US Caucasians and Koreans, its diagnostic accuracy was significantly lower and optimal cutoff scores for screening MDD were about 2 times higher in Koreans than in US Caucasians. Currently, various questionnaires for depression are in use for screening in or out the subjects for a wide range of studies including epidemiological studies, biological studies, and clinical trials. However, culture-specific cutoffs have been barely applied in those studies even if their subjects were multinational and/or multiethnic. If we uniformly apply a cutoff score of the CES-D estimated in US Caucasians to other ethnic groups when we conduct an epidemiological study on a multiethnic population, the CI of prevalence may be wider and the statistical power for finding risk factors may be lower in the populations with higher cutoff scores than in US Caucasians. If we apply a uniform cutoff score on the CES-D when we conduct an international clinical trial on new antidepressants, the US subjects may inevitably show greater depression severity than those enrolled in Korea, which may significantly confound the results of the trial such as therapeutic dosage, time to clinical response, or dropout rate. Therefore, it would be better to endorse culture-specific cutoff scores in the research with multiethnic populations, since it may not be feasible to develop a questionnaire that works equivalently in all ethnic groups. These cross-cultural issues may be equally important in terms of depression prevention and case management in clinical settings.

Our study has several limitations that should be noted. First, there were differences in sampling methods. Korean subjects were recruited from either a community sample (both nondepressed and depressed individuals) or from a hospital-based clinic (depressed patients). US Caucasians were enrolled in a federally supported study, with nondepressed participants approached based on the data of a volunteer registry and depressed patients recruited from the outpatient psychiatric and medical clinics and from the inpatient psychiatric service at Duke. Thus, comparisons of the nondepressed sample may have been affected by the ‘community status’ versus the ‘volunteer status’ of the two groups. Volunteers may have a more positive outlook and this may have positively influenced CES-D scores. Inclusion of an inpatient group in the US sample may have affected the results as well. In addition, considerable differences in the demographic characteristics between Korean and US Caucasian samples, although statistically adjusted in the analysis, may also have affected the results. The versions of the CES-D used in this study may represent another limitation. There were differences in the ordering of some questions and in the wording of others. A final issue pertains in the construct of statistical versus clinical significance. Although many of the differences in the CES-D item scores reached statistical significance, it is not clear how clinically meaningful the differences are. For example, many of the differences we report are for CES-D item scores of less than 1, a finding that may be hard to interpret clinically.

In conclusion, questionnaires for depression developed in the western culture should be well adapted culturally as well as well translated linguistically to ensure the comparability between ethnic groups [40]. In future studies on multiethnic populations, cross-cultural issues should be considered more carefully than before unless we develop a culture-free instrument for depression.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Independent Research Grant (IRG) from Pfizer Global Pharmaceuticals (Grant No. 06-05-039), the Grant for Developing Seongnam Health Promotion Program for the Elderly from Seongnam City Government in Korea (Grant No. 800-20050211), and US National Institute of Mental Health Grants P50 MH060451, R01 MH56846, and K24 MH70027.

References

- 1.Blazer D. The epidemiology of depression in late life. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1989;22:35–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts RE, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ, Strawbridge WJ. Does growing old increase the risk for depression? Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1384–1390. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Copeland JRM, Abou-Saleh MT, Blazer DG. Principles and Practice of Geriatric Psychiatry. ed 2. Chichester: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra R, Chan A, Ostbye T. Prevalence and correlates of clinically significant depressive symptoms among elderly people in Sri Lanka: findings from a national survey. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:227–236. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buys L, Roberto KA, Miller E, Blieszner R. Prevalence and predictors of depressive symptoms among rural older Australians and Americans. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16:33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations . Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision. New York: United Nations; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Pieper CF. The association of depression and mortality in elderly persons: a case for multiple, independent pathways. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M505–M509. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.8.m505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganguli M, Dodge HH, Mulsant BH. Rates and predictors of mortality in an aging, rural, community-based cohort: the role of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1046–1052. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang BY, Cornoni-Huntley J, Hays JC, Huntley RR, Galanos AN, Blazer DG. Impact of depressive symptoms on hospitalization risk in community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1279–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Diehr P, Simon G, Grembowski D, Katon W. Quality adjusted life years in older adults with depressive symptoms and chronic medical disorders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:15–33. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burroughs H, Lovell K, Morley M, Baldwin R, Burns A, Chew-Graham C. ‘Justifiable depression’: how primary care professionals and patients view late-life depression? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2006;23:369–377. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR. The efficiency of depression questionnaires for case finding in primary medical care. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:541–547. doi: 10.1007/BF02599556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr LK, Kerr LD., Jr Screening tools for depression in primary care: the effects of culture, gender, and somatic symptoms on the detection of depression. West J Med. 2001;175:349–352. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.5.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. Acculturation and manifestation of depressive symptoms among Korean-American older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:500–507. doi: 10.1080/13607860500193021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang Y, Small BJ, Haley WE. Cross-cultural comparability of the geriatric depression scale: comparison between older Koreans and older Americans. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5:31–37. doi: 10.1080/13607860020020618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang SM, Hahm B-J, Lee J-Y, Shin MS, Jeon HJ, Hong J-P, Lee HB, Lee D-W, Cho MJ. Cross-national difference in the prevalence of depression caused by the diagnostic threshold. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen CI, Magai C, Yaffee R, Walcott-Brown L. Racial differences in syndromal and subsyndromal depression in an older urban population. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1556–1563. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azocar F, Arean P, Miranda J, Munoz RF. Differential item functioning in a Spanish translation of the Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57:355–365. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehti AH, Johansson EE, Bengs C, Danielsson U, Hammarstrom A. ‘The western gaze’ – an analysis of medical research publications concerning the expressions of depression, focusing on ethnicity and gender. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31:100–112. doi: 10.1080/07399330903067861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park J, Lim S, Lim J, Kim K-I, Han M-K, Yoon I, Kim J-M, Chang Y-S, Chang C, Chin H, Choi E, Lee S, Park Y, Paik N-J, Kim T, Jang H, Kim K. An overview of the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLOSHA) Psychiatr Invest. 2007;4:84–95. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Youu S-W, Namkoong K, Kim S-J, Kim C-H, Chae J-H, Oh K-S, Min K-J, Choi Y-H, Kim Y-S, Noh J-S, Lee K-C, Jeon S-I, Oh D-J, Joo E-J, Park H-J. Validity of Korean version of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview. Anxiety Mood. 2006;2:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the geriatric depression scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho MJ, Kim KH. Diagnostic validity of the CES-D (Korean version) in the assessment of DSM-III-R major depression. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1993;32:381–399. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blazer D, Hughes DC, George LK. Age and impaired subjective support. Predictors of depressive symptoms at one-year follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180:172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association . Task Force on DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. ed 4. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts RE, Vernon SW. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: its use in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:41–46. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stricker L. Identifying test items that perform differently in population subgroups: a partial correlation index. Appl Psychol Meas. 1982;6:261–273. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorsuch RL. Factor Analysis. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan W, Ho R, Leung K, Chan D, Yung Y. An alternative method for evaluating congruence coefficients with procrustes rotation: a bootstrap procedure. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:378–402. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tucher LR. A Method for Synthesis of Factor Analysis Studies: Personal Research Section Report No 984. Washington: Department of Army; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. Acculturation and manifestation of depressive symptoms among Korean-American older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:500–507. doi: 10.1080/13607860500193021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwata N, Roberts RE. Age differences among Japanese on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: an ethnocultural perspective on somatization. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:967–974. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chien CP, Cheng TA. Depression in Taiwan: epidemiological survey utilizing CES-D. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 1985;87:335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golding JM, Aneshensel CS, Hough RL. Responses to depression scale items among Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic whites. J Clin Psychol. 1991;47:61–75. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199101)47:1<61::aid-jclp2270470110>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall JA, Bernieri FJ. Interpersonal Sensitivity: Theory and Measurement. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mui A. Self-reported depressive symptoms among black and Hispanic frail elders: a sociocultural perspective. J Appl Gerontol. 1993;12:170–180. [Google Scholar]