Abstract

Our objective was to resequence insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) to identify variants associated with obesity- and diabetes-related traits in Hispanic children. Exonic and intronic segments, 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of IRS2 (∼14.5 kb), were bidirectionally sequenced for single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) discovery in 934 Hispanic children using 3730XL DNA Sequencers. Additionally, 15 SNPs derived from Illumina HumanOmni1-Quad BeadChips were analyzed. Measured genotype analysis tested associations between SNPs and obesity and diabetes-related traits. Bayesian quantitative trait nucleotide analysis was used to statistically infer the most likely functional polymorphisms. A total of 140 SNPs were identified with minor allele frequencies (MAF) ranging from 0.001 to 0.47. Forty-two of the 70 coding SNPs result in nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions relative to the consensus sequence; 28 SNPs were detected in the promoter, 12 in introns, 28 in the 3′-UTR, and 2 in the 5′-UTR. Two insertion/deletions (indels) were detected. Ten independent rare SNPs (MAF = 0.001–0.009) were associated with obesity-related traits (P = 0.01–0.00002). SNP 10510452_139 in the promoter region was shown to have a high posterior probability (P = 0.77–0.86) of influencing BMI, fat mass, and waist circumference in Hispanic children. SNP 10510452_139 contributed between 2 and 4% of the population variance in body weight and composition. None of the SNPs or indels were associated with diabetes-related traits or accounted for a previously identified quantitative trait locus on chromosome 13 for fasting serum glucose. Rare but not common IRS2 variants may play a role in the regulation of body weight but not an essential role in fasting glucose homeostasis in Hispanic children.

Keywords: DNA resequencing, diabetes, body mass index, single nucleotide polymorphisms, indels, insulin receptor substrate 2

insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) is a compelling candidate gene for obesity, insulin resistance, and Type 2 diabetes given its role in insulin signal transduction and the manifestation of obesity, insulin resistance and β-cell failure in Irs2−/− mice (30), and yet human studies of common IRS2 variants have not demonstrated consistent effects (2–4, 34). IRS2 is a cytoplasmic signaling protein that mediates effects of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, and cytokines by acting as a relay protein between diverse receptor tyrosine kinases and downstream effectors (35, 36) and thereby accounting for the diverse actions of insulin (18). Structurally, IRS2 has many modified residues (phosphotyrosines, phosphoserines, and phosphothreonines) and a CpG island in the promoter region, which suggests high regulatory potential. Highly expressed in the hypothalamus as well as pancreatic islets, prefrontal cortex, adrenal cortex and adipocytes, IRS2 may play a key role in the integration of central control of energy homeostasis with peripheral insulin action and β-cell function (11, 36).

Human linkage and association studies have not demonstrated a consistent effect of IRS2 variants on insulin resistance or Type 2 diabetes (2–4, 19). Study cohorts, however, have been relatively small, and IRS2 genotyping has been limited. In Caucasian families with early-onset Type 2 diabetes, no linkage or mutations involving IRS2 were identified in 220 diabetic patients and 146 controls (3). In 150 Ashkenazi Jewish families, linkage was not detected between Type 2 diabetes and IRS2 (19). In a Danish cohort, IRS2 SNPs (codons 1057 and 879) were not associated with Type 2 diabetes or insulin secretion (2, 4). In 193 Italians with Type 2 diabetes and 200 controls, the same single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (codon 1057) was protective against Type 2 diabetes in lean individuals (25). In French Caucasian women, SNP (codon 1057) was associated with severe obesity (22). Bottomley et al. (9) sequenced the coding region of IRS2 in 161 European nonobese and obese adults with severe insulin resistance. Eight rare, nonsynonymous variants were identified, but there was no clear evidence that these variants had a pathogenic effect on insulin resistance.

Findings from our Viva La Familia genome-wide scan suggested that variation in IRS2 may contribute to childhood obesity and its comorbidities (13). We identified a highly significant quantitative trait locus (QTL) on chromosome 13q [logarithm of the odds (LOD) = 4.6] for fasting serum glucose and suggestive linkage for sICAM-1 (LOD = 2.5), total T4 (LOD = 1.7), and ghrelin (LOD = 1.2). Pleiotropy was found between fasting serum glucose and insulin and c-peptide, as might be expected given the pivotal role of insulin in glucose homeostasis.

The contribution of IRS2 variants to the high susceptibility for obesity and Type 2 diabetes among Hispanic children has not been investigated. In 2007–2008, 20.9% of Hispanic children, aged 2–19 yr, were classified as obese [≥95th percentile for body mass index (BMI) for age] (27). In 2001, the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes in Hispanic youth, aged 10–19 yr, was 0.48 cases per 1,000 (24). A positive family history was common for Type 2 diabetes (83%), and minorities were more likely to have a positive family history than non-Hispanic whites (odds ratio 1.96, confidence interval 1.69–2.27) (15).

Hence, the specific objectives of our study were: 1) to resequence exonic and intronic segments and 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of IRS2 (∼14.5 kb) to identify SNPs in 934 Hispanic children; 2) to perform measured genotype analysis to test for associations between genotype and the obesity- and diabetes-related traits; and 3) to perform Bayesian quantitative trait nucleotide (BQTN) analysis to test combinations of variants to statistically identify potentially functional genetic variants influencing obesity and diabetes risk in Hispanic children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Subjects

Subjects (n = 934) were from 319 Hispanic families enrolled in the Viva La Familia Study in 2000–2004. Anthropometric and body composition measurements were performed on parents and children. Blood samples were drawn for biochemistry profiling of the children and genotyping of children and parents. Subjects and study procedures are described in detail in a previous publication (12). All children and their parents gave written informed consent or assent. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subject Research for Baylor College of Medicine and Affiliated Hospitals and the Texas Biomedical Research Institute.

In brief, the Viva La Familia Study cohort consisted of a total of 631 parents and 1,030 children. The majority of the parents were either overweight (34%) or obese (57%). Type 2 diabetes was reported in 11 and 8% of the mothers and fathers, respectively. Fifty-one percent of the children were above the 95th BMI percentile with z-scores ranging from 2.3 to 4.5 (21).

Anthropometry and Body Composition

Body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg was measured with a digital balance and height to the nearest 1 mm was measured with a stadiometer. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Waist circumference was measured at a level midway between the inferior border of the rib cage and superior border of the iliac crest with a nonstretchable tape measure. Total body estimates of fat-free mass (FFM), fat mass (FM), and percent FM were measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry using a Hologic Delphi-A whole-body scanner (Delphi-A; Hologic, Waltham, MA).

Fasting Biochemistries

A blood sample was drawn in the morning after a 12-h fast. Serum samples were obtained from whole blood after clotting. Fasting serum concentration of glucose was measured by enzymatic-colorimetric techniques using the GM7 Analyzer (Analox Instruments, Lundeburg, MA) [coefficient of variation (CV) = 2.4%]. Commercial radioimmunoassay kits were used to measure fasting serum concentrations of insulin (CV = 7.1%), C-peptide (CV = 4.2%), and leptin (CV = 4.6%) (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO) and ghrelin (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, CA) (CV = 7%). Total and free triiodothyronine (T3) were measured by radioimmunoassay kits (Diagnostic Products, Los Angeles, CA) (CV = 6.85, 9.5%). C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured using a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay (American Laboratory Products, Windham, NH) (CV = 11.6%). Plasma soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) was measured using a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay (CV = 6.1%) (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Triglycerides were assayed enzymatically using lipase, glycerol kinase, glycerol phosphate oxidase, and peroxidase supplied by Thermo Electron (Louisville, CO). Total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) were determined using cholesterol esterase, cholesterol oxidase, and peroxidase supplied by Thermo Electron. Insulin resistance was estimated by the HOMA (homoeostatic model assessment) method that is computed as HOMA = [fasting serum insulin (mU/ml) * fasting serum glucose (mmol/l)]/22.5 (26).

Genetic Analysis

Resequencing.

IRS2 is a 1,338-amino acid protein with a well-conserved pleckstrin homology domain at the extreme NH2 terminus, followed by a phosphotyrosine binding domain that binds to phosphorylated NPXY motifs, and a COOH-terminal region with multiple tyrosine phosphorylation sites (35). The IRS2 gene has 32,731 bp. Exonic and intronic segments, and 5′ and 3′ flanking regions (a total of 29 amplicons) were sequenced in 934 children. IRS2 has one main coding exon ∼4 kb in length and a short coding piece in the 3′ exon. There are three conserved regions extending through 1.5 kb upstream from the IRS2 promoter and a prominent CpG island. Validated primer pairs for this project were used to amplify exonic and intronic segments, and 5′ and 3′ flanking regions from 934 samples of DNA and a negative and positive control per 384-well plate quadrant [8 no-DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) control wells included for quality control].

The target sequences were amplified in ∼500 bp fragments. Exon specific primer pairs were designed using the program Primer 3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/). Universal M13 forward or reverse primer tails were attached to each amplicon-specific primer. PCR reactions were established using the Qiagen PCR kit, with individual amplicon size of 270–550 bp. PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels and purified using ExoSap (USB, Cleveland, OH). Bidirectional sequencing of each fragment was performed separately using big dye terminator sequencing chemistry on 3730XL DNA Sequencers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The average amplicon sequencing success rate was 92%. The sequences were analyzed using the program SNPdetector v. 3.0 (38). Variant bases were annotated with Reference SNP IDs based on dbSNP build 131. SNPs were confirmed manually by viewing raw sequence traces in CONSED (16).

Our resequencing strategy was to interrogate as much of the IRS2 gene region as possible within our budget. Our above resequencing strategy was designed to cover the coding regions, the promoter region, and a modest number of 5′- and 3′-untranslated region (UTR) conserved noncoding regions. Because we opportunistically had additional SNP data from the Illumina panel, we chose to augment coverage in the 5′- and 3′-UTR regions. Hence, 15 SNPs located in the IRS2 region were selected: three SNPs are just outside the sequenced region, one upstream and two downstream. The other 12 SNPs are located within the intron sequence of IRS2 not captured by the primer design. Although our intent for using the Illumina chip data was not as an additional quality control step, six additional SNPs on the Illumina chip were also identified by sequencing.

These 15 additional SNPs in the intronic and 5′- and 3′-UTRs regions were genotyped as part of the Illumina HumanOmni1-Quad v1.0 BeadChips using the Infinium HD single-base extension (SBE) assay (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Genomic DNA was whole genome amplified, fragmented, and hybridized to the BeadChips where SBE occurs using fluorescence-labeled nucleotides. Fluorescence intensities were detected by scanning the BeadChips on the Illumina BeadStation 500GX and analyzed with the GenomeStudio software from Illumina. Cluster calls were checked for accuracy. For an assessment of consistency in allele calling, replicate samples were included on our genotyping plates. Further quality control assessment is performed using sample-dependent and sample-independent controls included on the Illumina BeadChips.

Statistical Methods

All traits were transformed to meet the assumption of normality before entering the genetic analyses to avoid inflating type 1 error. Age, age2, sex, and their interactions were used as covariates and simultaneously estimated in these models. All genetic analyses were performed using the Sequential Oligogenic Linkage Analysis Routines (SOLAR) computer package (1). Bivariate analyses were conducted to partition the phenotypic correlations (ρP) between two traits into additive genetic (ρG) and environmental correlations (ρE). Genotype frequencies for each SNP were estimated allowing for nonindependence due to kinship (5, 6) and were tested for departures from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Estimates of linkage disequilibrium between SNPs were determined by calculating pair-wise D′ and r2 statistics.

Measured genotype analysis.

As a first step in investigating the association between the SNPs in IRS2 and our obesity- and diabetes-related traits, we employed a measured genotype analysis (8), as implemented in SOLAR (1). This approach extends the classical variance components-based biometrical model to account for both the random effects of kinship and the main effects of SNP genotypes. Variance components are modeled as random effects, e.g., additive genetic effects and random environmental effects and the effects of covariates such as age and sex are modeled as fixed effects on the main trait. For each SNP, we compared this saturated model with a null model in which the main effect of the SNP is constrained to zero. The test statistic, twice the difference in loge (likelihood) between the saturated model and the SNP-specific null, is distributed as χ2 with one degree of freedom.

BQTN analysis.

The measured genotype analysis provides the prior probability that each SNP is associated with a trait of interest. However, it is not known a priori whether a gene influencing a given trait has one common variant affecting the trait in all pedigrees or multiple variants with potentially interacting effects. BQTN analysis was implemented in SOLAR to statistically identify the most likely functional SNPs associated with a trait (5). For a chosen set of SNPs, this approach evaluates the likelihood of all possible association models, while providing a penalty for overparameterization, to identify the subset of SNPs with the highest posterior probability of association with the trait. Although the major purpose of BQTN analysis is to statistically identify the most likely functional variant, it has also been proved extremely useful in cases where a subset of SNPs have been genotyped.

Bayesian model selection identifies the set of variants that optimally predicts the trait. In a Bayesian framework, two competing hypotheses (models) are compared by evaluation of the Bayes factor, which is the ratio of the integrated likelihoods of the competing models (20). For each hypothesis, a Bayesian information criterion (BIC) is defined with reference to a single null model (in our case, the random effects model without the SNPs) and is used to assess whether the BQTN model explains sufficient variation in the trait to justify the number of parameters used (6). The magnitude of the BIC difference provides an estimate of the evidence of support for one model over another. For example, a BIC difference greater than two units provides support for one model over another with a posterior probability of 75%. The BQTN approach also accounts for model uncertainty and thus provides the posterior probability that each variant is associated with the trait of interest. This variant-specific posterior probability is a measure of the evidence that a particular variant is likely to be functional or in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) with a functional variant. This approach has been shown to provide accurate determination of functional variants in conditions where the variants have been identified (5, 6, 14, 31).

RESULTS

Obesity- and Diabetes-Related Traits

Obesity- and diabetes-related traits of the 934 nonobese and obese children in the Viva La Familia cohort are summarized in Table 1. The additive genetic correlations between the obesity- and diabetes-related traits are shown in Table 2. The overall phenotypic correlation between fasting glucose and BMI in this cohort was statistically significant (ρP = 0.20, P = 5.71E-09). However, the bivariate analyses indicated that the phenotypic correlation was not driven by the genetic correlation. The additive genetic correlation between fasting glucose and BMI was not statistically significant [ρG = 0.10 (0.13), P = 0.45], whereas the environmental correlation was significant [ρE = 0.30 (0.10), P = 0.004].

Table 1.

Obesity- and diabetes-related traits of children enrolled in Viva La Familia Study (n = 934)

| Nonobese Boys | Obese Boys | Nonobese Girls | Obese Girls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 209 | 257 | 246 | 222 |

| Age, yr | 11.1 ± 4.2 | 11.3 ± 3.5 | 10.4 ± 4.5 | 10.8 ± 3.7 |

| Weight, kg | 43.8 ± 19.9 | 70.6 ± 29.7 | 37.7 ± 17.1 | 63.4 ± 24.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 20.0 ± 3.7 | 30.5 ± 7.0 | 19.5 ± 3.8 | 29.5 ± 6.4 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 66.5 ± 11.8 | 89.2 ± 16.6 | 61.7 ± 10.2 | 83.4 ± 14.7 |

| Fat-free mass, kg | 33.8 ± 15.5 | 42.0 ± 15.8 | 26.0 ± 10.6 | 36.8 ± 12.6 |

| Fat mass, kg | 10.2 ± 5.6 | 26.3 ± 11.3 | 11.7 ± 7.0 | 26.7 ± 11.7 |

| Fat mass, % weight | 22.8 ± 5.9 | 37.9 ± 5.8 | 29.2 ± 6.0 | 41.0 ± 5.0 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 91 ± 7 | 94 ± 8 | 89 ± 11 | 94 ± 18 |

| Insulin, μU/ml | 12.1 ± 8.0 | 29.4 ± 20.3 | 13.5 ± 8.8 | 33.1 ± 21.7 |

| C-peptide, ng/ml | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 2.0 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 1.8 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.8 ± 2.0 | 6.9 ± 5.0 | 3.1 ± 2.7 | 7.9 ± 6.2 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 50 ± 12 | 44 ± 10 | 51 ± 12 | 43 ± 9 |

| Total T3, ng/dl | 145 ± 24 | 152 ± 24 | 148 ± 25 | 152 ± 26 |

| Free T3, pg/ml | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 0.8 |

| CRP, ng/ml | 601 ± 875 | 1696 ± 1575 | 687 ± 960 | 1777 ± 1743 |

| sICAM-1, pg/ml | 263 ± 113 | 293 ± 121 | 261 ± 93 | 280 ± 103 |

| Leptin, ng/ml | 5.6 ± 4.1 | 23 ± 12 | 12 ± 9 | 30 ± 16 |

| Ghrelin, ng/ml | 43 ± 17 | 33 ± 14 | 45 ± 17 | 32 ± 12 |

Values are means ± SD. BMI, body mass index; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; T3, triiodothyronine; CRP, C-reactive protein; sICAM-1, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1.

Table 2.

Additive genetic correlations between obesity- and diabetes-related traits of children enrolled in Viva La Familia

| Weight | BMI | Waist | FFM | FM | % FM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.10 (0.13) | 0.09 (0.13) | −0.03 (0.14) | −0.03 (0.14) | 0.02 (0.12) |

| Insulin | 0.54 (0.11) | 0.62 (0.09) | 0.68 (0.08) | 0.31 (0.14) | 0.58 (0.10) | 0.59 (0.10) |

| C-peptide | 0.28 (0.11) | 0.36 (0.10) | 0.32 (0.10) | 0.11 (0.12) | 0.32 (0.10) | 0.34 (0.10) |

| HOMA-IR | 0.50 (0.11) | 0.60 (0.10) | 0.64 (0.09) | 0.28 (0.15) | 0.54 (0.11) | 0.55 (0.10) |

| HDL | −0.17 (0.12) | −0.10 (0.11) | −0.15 (0.11) | −0.28 (0.11) | −0.14 (0.11) | −0.13 (0.10) |

| Total T3 | −0.12 (0.14) | −0.04 (0.14) | 0.01 (0.14) | −0.37 (0.15) | −0.02 (0.14) | 0.03 (0.12) |

| Free T3 | −0.12 (0.13) | −0.16 (0.13) | −0.10 (0.12) | −0.10 (0.13) | −0.03 (0.13) | 0.04 (0.12) |

| CRP | 0.35 (0.13) | 0.44 (0.12) | 0.45 (0.11) | 0.33 (0.14) | 0.40 (0.12) | 0.44 (0.11) |

| sICAM-1 | −0.22 (0.12) | −0.16 (0.11) | −0.14 (0.11) | −0.13 (0.11) | −0.17 (0.11) | −0.06 (0.10) |

| Leptin | 0.67 (0.08) | 0.70 (0.07) | 0.68 (0.07) | 0.30 (0.14) | 0.78 (0.05) | 0.78 (0.05) |

| Ghrelin | −0.43 (0.11) | −0.50 (0.10) | −0.49 (0.10) | −0.34 (0.11) | −0.48 (0.10) | −0.46 (0.09) |

Additive genetic correlation (ρG) ± SE adjusted for age, sex, age2, age × sex, and age2 × sex. Statistically significant ρG values >0.20. FFM, fat-free mass; FM, fat mass.

Resequencing And Genotyping

A total of 140 SNPs were identified with minor allele frequencies (MAF) ranging from 0.001 to 0.47. Of the 140 SNPs, 35 (25%) are described in the database dbSNP [National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), build 131]. Forty-two of the 70 coding SNPs result in nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions relative to the consensus sequence; 28 SNPs were detected in the promoter, 12 in the intron, 28 in the 3′-UTR, and 2 in 5′-UTR. The genotypic distributions of all 140 SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Thirty-three SNPs were removed from further consideration due to high LD [correlation (ρ) ≥0.9]. The 40 SNPs with MAF ≥0.01 are presented in Table 3; all 140 SNPs are presented online as Supplemental Material.1

Table 3.

Identification of SNPs in the IRS2 gene with MAF ≥0.01 in 934 Hispanic children enrolled in Viva La Familia cohort

| SNP ID | Position on Chr 13 | Left Flank. Right Flank | Major Allele | Minor Allele | MAF | Type | Reference AA | Variable AA | Protein Position | Reference Codon | Codon Position | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs1034104 | 109203128 | TGGATGCACG.ACAAATGTTT | G | C | 0.129 | 3′UTR | |||||

| 2 | rs9587979 | 109203242 | TTTCTTCTTT.TATTCTTGAT | G | A | 0.011 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 3 | rs41275080 | 109204832 | ATACCACCCA.TGATGCCTAT | T | C | 0.015 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 4 | 10467453_203 | 109205580 | TTTTTCTTTT.GTTTTTTTTG | T | G | 0.252 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 5 | 10467453_204 | 109205581 | TTTTCTTTTT.TTTTTTTTGT | G | T | 0.025 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 6 | rs1044364 | 109205647 | AATACGTTTT.TAAAAATCAA | T | C | 0.096 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 7 | rs2289047 | 109205816 | ACATCTACAT.GAGAAGATTA | C | A | 0.46 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 8 | rs2289046 | 109205907 | CCCAATACAG.TGATTTTCAA | T | C | 0.366 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 9 | rs7320328 | 109206094 | TGGACCATTT.AATAAGGCCG | C | A | 0.015 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 10 | rs1865434 | 109206609 | TTTAATGATA.TCTCTGACAT | T | C | 0.083 | 3′-UTR | |||||

| 11 | rs9515119 | 109207337 | TCAAACTTTC.TATGTTCCAG | A | C | 0.448 | intron | |||||

| 12 | rs754204 | 109209569 | CACGGTAAAG.GAGAACTGTG | G | A | 0.399 | intron | |||||

| 13 | rs913949 | 109209797 | GGAAAAGGCT.GAGCACACCT | A | G | 0.211 | intron | |||||

| 14 | rs12584136 | 109217355 | AGACATTTTC.AATGCTCATG | C | A | 0.094 | intron | |||||

| 15 | rs9559646 | 109217405 | CCCAGATCTG.GAAATGCTTT | G | A | 0.351 | intron | |||||

| 16 | rs9521509 | 109219452 | CTCAATGGTA.CTCAGCGTCT | G | A | 0.463 | intron | |||||

| 17 | rs4773088 | 109219885 | CTTAACATCT.TAAGACCGGC | G | A | 0.219 | intron | |||||

| 18 | rs2241745 | 109220532 | GGGGCTGTGG.TGGCAGGAAA | A | G | 0.081 | intron | |||||

| 19 | rs7999797 | 109224001 | CCACTCAGTA.ACACCGTCCA | G | A | 0.468 | intron | |||||

| 20 | rs4771647 | 109225210 | TTTTAACCCC.AGAGAAGAGT | A | C | 0.215 | intron | |||||

| 21 | rs7981170 | 109229575 | AAACATTACC.ACATAACCCC | G | A | 0.156 | intron | |||||

| 22 | rs11618950 | 109232311 | CCAAAAAGTG.GAGCAGTGAA | G | A | 0.128 | intron | |||||

| 23 | rs1805097 | 109233232 | TGAGGCGGCG.CCGGGCCCTG | T | C | 0.441 | missense mutation | Gly | Asp | 1057 | GGC | 2 |

| 24 | rs9583424 | 109233303 | CCGGCGGCGG.GGCGGCGGCT | T | C | 0.155 | coding synonymous | Pro | Pro | 1033 | CCA | 3 |

| 25 | 9967402_329 | 109233309 | GCGGTGGCGG.GGCTGCAGAG | C | T | 0.014 | coding synonymous | Pro | Pro | 1031 | CCG | 3 |

| 26 | rs12853546 | 109233915 | TGCGCCCCAC.GGGGAGCTCA | G | A | 0.147 | coding synonymous | Pro | Pro | 829 | CCC | 3 |

| 27 | rs4773092 | 109233954 | TGTCCCCGCC.CAGGTGTAGG | G | A | 0.301 | coding synonymous | Cys | Cys | 816 | TGT | 3 |

| 28 | rs3742210 | 109234233 | AGCCGCCCCC.CTCGCCGGGA | A | G | 0.293 | coding synonymous | Ser | Ser | 723 | AGC | 3 |

| 29 | 9967406_432 | 109234890 | CTGGGCTGGA.CCGTACTCGT | G | T | 0.012 | coding synonymous | Gly | Gly | 504 | GGC | 3 |

| 30 | 9967410_456 | 109236513 | CGGCCGCCCG.CCGATCACGC | C | T | 0.011 | 5′-UTR | |||||

| 31 | 9966358_25 | 109237356 | AGCTTCCGCC.GGGAGGGGGC | G | A | 0.014 | promoter | |||||

| 32 | 10510452_28 | 109237452 | TGGGCGGCGA.CCGGGCCGTG | G | A | 0.015 | promoter | |||||

| 33 | 10510452_31 | 109237455 | GCGGCGAGCC.GGCCGTGCTC | G | A | 0.012 | promoter | |||||

| 34 | rs63193461 | 109237565 | CCGTCTCCCG.CCGCATCTCC | T | G | 0.13 | promoter | |||||

| 35 | 10510452_201 | 109237625 | CCGCGGCCGC.GGTTCGCGAG | G | C | 0.119 | promoter | |||||

| 36 | 10510452_333 | 109237757 | GCCATTCACT.GTCAGCTTGT | T | A | 0.016 | promoter | |||||

| 37 | rs3803239 | 109237955 | CAGGGGCGTC.TCTCCCCCCA | C | G | 0.116 | promoter | |||||

| 38 | 9966359_243 | 109237983 | AGGAGCACCC.CTTCCTTCCT | C | T | 0.012 | promoter | |||||

| 39 | 10467450_40 | 109238040 | CCCCTTCCTT.CACAGGGGCG | C | G | 0.069 | promoter | |||||

| 40 | rs4773094 | 109239484 | CCAGACTGGG.ACAAAAGAGA | G | A | 0.165 | promoter |

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) ID in dbSNP (NCBI, build 131) or assigned ID for novel SNPs by investigators. IRS2, insulin receptor sustrate 2; MAF, minor allele frequency; UTR, untranslated region. DNA sequence in positive orientation.

Two insertion/deletions (indels) were detected in the promoter region at chromosomal positions 109237583 and 109237738 (NCBI build 131) with MAFs corresponding to 0.317 and 0.016, respectively.

Measured Genotype Analysis

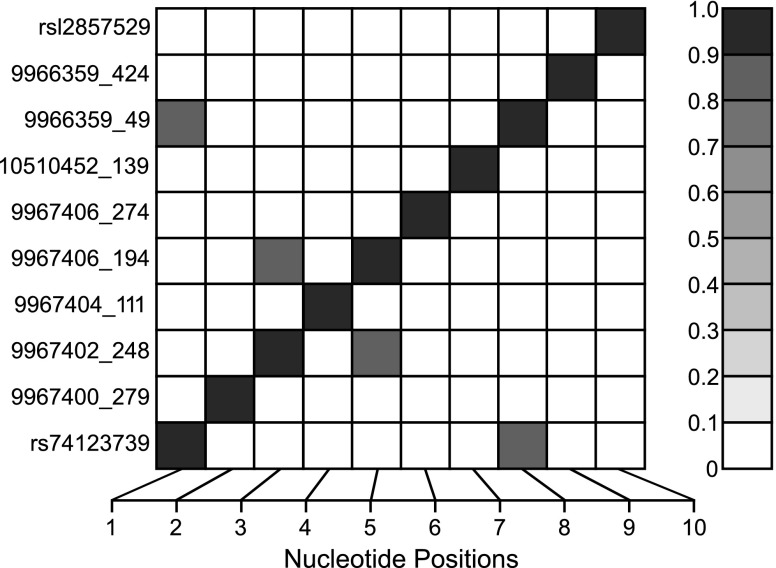

Measured genotype analysis was performed between the 140 identified SNPs and two indels and the obesity- and diabetes-related traits. Ten SNPs were found to be associated with the measured traits at nominal P values ≤0.01, uncorrected for multiple testing (Table 4, Fig. 1). Associations were observed between IRS2 variants and weight, BMI, waist circumference, FFM, FM, and fasting serum levels of HDL, total and free T3, CRP, sICAM-1, leptin, and ghrelin. With respect to our original QTL, three SNPs (9967402_100, rs73606275, and rs35927012) were marginally associated with fasting serum glucose (P values = 0.02–0.05) but did not withstand correction for multiple testing. The indels were not significantly associated with any of the obesity- and diabetes-related traits.

Table 4.

Measured genotype analysis of SNPs identified in IRS2 with obesity- and diabetes-related traits in children

| SNP | rs12857529 | rs74123739 | 9966359_49 | 10510452_139 | 9967402_248 | 9967400_279 | 9967404_111 | 9966359_424 | 9967406_194 | 9967406_274 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor allele | A | C | A | G | A | A | T | C | A | A |

| frequency | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Type | promoter | 3′-UTR | promoter | promoter | coding synon | missense mutation | missense mutation | promoter | nonsense mutation | missense mutation |

| Glucose | 0.973 | 0.295 | 0.382 | 0.383 | 0.753 | 0.300 | 0.859 | 0.657 | 0.736 | 0.737 |

| Insulin | 0.507 | 0.081 | 0.057 | 0.020 | 0.685 | 0.333 | 0.129 | 0.727 | 0.687 | 0.453 |

| Weight | 0.006 | 0.037 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.102 | 0.129 | 0.351 | 0.033 | 0.104 | 0.362 |

| BMI | 0.014 | 0.029 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.105 | 0.103 | 0.084 | 0.031 | 0.108 | 0.437 |

| Waist | 0.018 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 0.0004 | 0.109 | 0.076 | 0.098 | 0.102 | 0.114 | 0.484 |

| FFM | 0.007 | 0.115 | 0.121 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.027 | 0.805 | 0.046 | 1.000 | 0.211 |

| FM | 0.024 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.073 | 0.063 | 0.245 | 0.006 | 0.077 | 0.610 |

| HDL | 0.621 | 0.792 | 0.847 | 0.061 | 0.00002 | 0.563 | 0.599 | 0.705 | 0.00002 | 0.200 |

| Total T3 | 0.197 | 0.184 | 0.167 | 0.680 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.482 | 0.480 | 0.007 | 0.822 |

| Free T3 | 0.199 | 0.518 | 0.420 | 0.240 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.117 | 0.153 | 0.006 | 0.672 |

| CRP | 0.038 | 0.783 | 0.626 | 0.033 | 0.028 | 0.770 | 0.009 | 0.606 | 0.029 | 0.778 |

| sICAM-1 | 0.946 | 0.498 | 0.408 | 0.817 | 0.021 | 0.631 | 0.006 | 0.889 | 0.026 | 0.001 |

| Leptin | 0.343 | 0.049 | 0.024 | 0.050 | 0.360 | 0.068 | 0.031 | 0.010 | 0.354 | 0.881 |

| Ghrelin | 0.412 | 0.675 | 0.762 | 0.006 | 0.150 | 0.015 | 0.021 | 0.030 | 0.153 | 0.200 |

All measured genotype analysis models included age, sex, age × sex, age2, and age2 × sex as covariates (n = 934). Nominal P values are shown uncorrected for multiple testing. P values ≤0.01 are highlighted in boldface.

Fig. 1.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) linkage disequilibrium structure for the nominally significant SNPs in the insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) gene. SNPs are indicated by their physical order within or nearby the gene on the x-axis. The degree of correlation (ρ) between SNP pairs is indicated by the intensity of shading in the small squares of the central figure with perfect correlation between identical SNPs along the diagonal.

BQTN Analysis

The 10 nominally associated SNPs were analyzed by the BQTN method to estimate the posterior probabilities that any one variant or combination of variants has an effect on the measured traits. SNP 10510452_139 in the promoter region was shown to have a high posterior probability (P = 0.77–0.86) of influencing BMI, fat mass, and waist circumference in Hispanic children. The minor allele for SNP 10510452_139 was detected in two unrelated pedigrees among five obese children, all with BMIs >99th percentile. The proportion of variance contributed by the SNPs is shown in Table 5 for all 10 nominally significant SNPs. SNP 10510452_139 contributed the highest percentage of the variance (between 2 and 4%) in body weight and composition.

Table 5.

Percent of the population variance contributed by the nominally significant SNPs (%)

| SNP | rs12857529 | rs74123739 | 9966359_49 | 10510452_139 | 9967402_248 | 9967400_279 | 9967404_111 | 9966359_424 | 9967406_194 | 9967406_274 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor allele | A | C | A | G | A | A | T | C | A | A |

| frequency | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Type | promoter | 3′-UTR | promoter | promoter | coding synon | missense mutation | missense mutation | promoter | nonsense mutation | missense mutation |

| Glucose | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0 |

| Insulin | 0.002 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 1.40 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| Weight | 0.40 | 0.01 | 1.10 | 2.90 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| BMI | 0.20 | 0.80 | 1.20 | 2.80 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Waist | 0.20 | 0.80 | 1.20 | 3.10 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| FFM | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 3.60 | 0 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.70 | 0 | 0.30 |

| FM | 0.23 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 3.10 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 0.20 | 0.05 |

| HDL | 0 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.77 | 0.09 |

| Total T3 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.90 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.40 | 0 |

| Free T3 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.02 |

| CRP | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1.10 | 0.43 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.02 |

| sICAM-1 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.90 | 0 | 0.50 | 0.90 |

| Leptin | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Ghrelin | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 2.20 | 0.20 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

DISCUSSION

Resequencing of IRS2 in 934 Hispanic children predisposed to obesity and Type 2 diabetes revealed multiple, rare variants that may exert an effect on body weight regulation. Our experimental approach to identify likely functional polymorphisms within IRS2 involved enumeration of genetic variants in a large set of resequenced individuals, followed by measured genotype analysis and Bayesian model selection and averaging. For each putative SNP, a posterior probability of effect was obtained to prioritize SNPs for future intensive molecular functional analysis. Our resequencing strategy designed to cover the coding regions, the promoter region, and a modest number of 5′- and 3′-UTR conserved noncoding regions represents the largest effort to date to enumerate IRS2 variants in a human population.

Our major study finding suggests a role of IRS2 in energy homeostasis and body weight regulation in Hispanic children. Strong associations were seen between IRS2 variants and weight, BMI, waist circumference, FFM, and FM. Our BQTN analysis statistically identified a novel variant in the promoter region that may be involved in the regulation of body weight. This SNP (10510452_139) was detected in two unrelated pedigrees among five children with severe obesity (BMIs >99th percentile). Our findings may be specific to the Hispanic population, since frequencies of rare variants in a given genomic region may vary greatly from one ethnic group to another due to different evolutionary histories including genetic drift and bottlenecks (7). Although this rare variant was detected only in a few families, on a population basis it could contribute between 2–4% of the variance in body weight and composition.

The mechanism by which genetic heterogeneity in the IRS2 gene may impact energy homeostasis and body weight regulation is unclear. However, evidence from Irs2−/− mice support a role of Irs2 in the hypothalamic control of energy homeostasis and body weight regulation (11, 37). Female Irs2−/− mice consumed 30% more food, weighed 20% more, and stored twice the amount of body fat than controls. Mechanistically, leptin-stimulated phosphorylation of STAT-3 in the hypothalamus was inactivated in the Irs2−/− mice, disrupting appetite control and body weight regulation. Acting as an integrator of energy homeostasis, IRS2 could underlie the close relationship between obesity, peripheral insulin resistance, and eventual β-cell failure (36). Our results in Hispanic children are consistent with the possibility that partial dysregulation of IRS2 may contribute to the early development of obesity that predisposes to Type 2 diabetes.

In contrast to findings from murine models (30) but perhaps more consistent with human studies (2–4, 19), our analysis did not reveal any statistically significant associations between IRS2 variants and fasting serum glucose, insulin, C-peptide, or HOMA-IR. Consequently, IRS2 variants did not account for our original QTL on chromosome 13q for fasting serum glucose. The lack of association between IRS2 variants and fasting serum glucose might be attributable to compensatory overlap between IRS1 and IRS2 proteins (10, 18) or mimicking by environmental and physiological factors that affect glucose metabolism (36) or, indeed, another gene responsible for the QTL. This QTL encompasses 27 genes, half of which are hypothetical proteins of unknown function. In fact, the individuals harboring the rare IRS2 variants did not belong to the families contributing to the linkage signal for glucose. Pleiotropy was not seen between fasting glucose and body weight, suggesting different, independent genetic effects are acting on these two traits. Even though IRS2 was a strong positional candidate gene for our QTL for fasting glucose, the identified genetic variants were not associated with fasting glucose nor did they account for our linkage signals. This “negative” finding is important in and of itself; furthermore, our investigations led us to identify an IRS2 promoter variant that statistically has a high likelihood of being effective in the regulation of body weight and composition.

Our resequencing of IRS2 represents the largest effort to date to enumerate IRS2 variants in a human population. Until now, resequencing of IRS2 had been restricted to the coding region. Our resequencing effort demonstrated considerable within locus variant heterogeneity of IRS2. In addition to 70 coding SNPs, SNPs were detected in the promoter (28), intron (12), 3′-UTR (28), and 5′-UTR (2). Two indels also were detected in the promoter region. The common alleles identified in IRS2 appeared to be neutral, whereas rare variants were associated with disease susceptibility, supporting the “common disease rare variant hypothesis,” that there is extreme allelic heterogeneity for complex traits and that multiple rare variants with moderate to high penetrance may be responsible for complex diseases (7, 17, 23, 28, 29). A significant proportion of the inherited susceptibility to common chronic diseases may be due to the summation of the effect of a series of low-frequency dominantly and independently acting variants of different genes, each conferring a moderate but detectable increase in relative risk (7).

Our study has demonstrated the utility of deep resequencing of genes for identification of low-frequency alleles contributing to complex diseases. Understanding the genetic architecture of complex diseases such as obesity or diabetes is of great interest to the biomedical community. While whole genome association studies based on genotyping predominantly high-frequency SNPs have identified SNPs associated with obesity and diabetes, the variants account for only a small fraction of observed phenotypic variation (32, 33). In contrast, deep resequencing of putative genes has the potential to reveal low-frequency alleles contributing to complex diseases, such as the novel variant detected in the IRS2 promoter region in this study.

Conclusion

Rare but not common IRS2 variants may play a role in the regulation of body weight but not an essential role in fasting glucose homeostasis in Hispanic children.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant DK-080457 and the USDA/ARS (Cooperative Agreement 6250-51000-053). Work performed at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute in San Antonio, TX, was conducted in facilities constructed with support from the Research Facilities Improvement Program of the National Center for Research Resources, NIH (C06 RR-013556, C06 RR-017515).

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the USDA, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the families who participated in the Viva La Familia Study. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Mercedes Alejandro and Marilyn Navarrete for study coordination; and Sopar Seributra for nursing; and Theresa Wilson, Maurice Puyau, Firoz Vohra, Anne Adolph, Nitesh Mehta, Roman Shypailo, JoAnn Pratt, Maryse Laurent, Grace-Ellen Meixner, Margie Britten, and Maria del Pilar Villegas for technical assistance.

The authors' responsibilities were as follows: N. F. Butte, S. A. Cole, and A. G. Comuzzie participated in the conception, design, analysis, data interpretation, and redaction of the manuscript; D. M. Muzny, D. A. Wheeler, and R. A. Gibbs performed the resequencing; K. Chang and A. Hawes were responsible for the informatics; V. S. Voruganti and K. Haack participated in the genetic statistical analyses. All authors played a role in the data interpretation and writing of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work is a publication of the U.S. Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service (USDA/ARS) Children's Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, Texas.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1. Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet 62: 1198–1211, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Almind K, Frederiksen SK, Bernal D, Hansen T, Ambye L, Urhammer S, Ekstrom CT, Berglund L, Reneland R, Lithell H, White MF, Van Obberghen E, Pedersen O. Search for variants of the gene-promoter and the potential phosphotyrosine encoding sequence of the insulin receptor substrate-2 gene: evaluation of their relation with alterations in insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia 42: 1244–1249, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bektas A, Warram JH, White MF, Krolewski AS, Doria A. Exclusion of insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS-2) as a major locus for early-onset autosomal dominant type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 48: 640–642, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernal D, Almind K, Yenush L, Ayoub M, Zhang Y, Rosshani L, Larsson C, Pedersen O, White MF. Insulin receptor substrate-2 amino acid polymorphisms are not associated with random type 2 diabetes among Caucasians. Diabetes 47: 976–979, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blangero J, Goring HH, Kent JW, Williams JT, Peterson CP, Almasy L, Dyer TD. Quantitative trait nucleotide analysis using Bayesian model selection. Hum Biol 77: 541–559, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blangero J, Williams JT, Iturria SJ, Almasy L. Oligogenic model selection using the Bayesian Information Criterion: linkage analysis of the P300 Cz event-related brain potential. Genet Epidemiol 17: S67–S72, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bodmer W, Bonilla C. Common and rare variants in multifactorial susceptibility to common diseases. Nat Genet 40: 695–701, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boerwinkle E, Chakraborty R, Sing CF. The use of measured genotype information in the analysis of quantitative phenotypes in man. I. Models and analytical methods. Ann Hum Genet 50: 181–194, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bottomley WE, Soos MA, Adams C, Guran T, Howlett TA, Mackie A, Miell J, Monson JP, Temple R, Tenenbaum-Rakover Y, Tymms J, Savage DB, Semple RK, O'Rahilly S, Barroso I. IRS2 variants and syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Diabetologia 52: 1208–1211, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brady MJ. IRS2 takes center stage in the development of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 114: 886–888, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burks DJ, de Mora JF, Schubert M, Withers DJ, Myers MG, Towery HH, Altamuro SL, Flint CL, White MF. IRS-2 pathways integrate female reproduction and energy homeostasis. Nature 407: 377–382, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Butte NF, Cai G, Cole SA, Comuzzie AG. Viva La Familia Study: genetic and environmental contributions to childhood obesity and its comorbidities in the Hispanic population. Am J Clin Nutr 84: 646–654, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cai G, Cole SA, Butte NF, Voruganti VS, Comuzzie AG. A quantitative trait locus (QTL) on chromosome 13q affects fasting glucose levels in Hispanic children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 4893–4896, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Curran JE, Jowett JBM, Elliott KS, Gao Y, Gluschenko K, Wang J, Azim DM, Cai G, Mahaney MC, Comuzzie AG, Dyer TD, Walder KR, Zimmet P, MacCluer JW, Collier GR, Kissebah AH, Blangero J. Genetic variation in selenoprotein S influences inflammatory response. Nat Genet 37: 1234–1241, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilliam LK, Liese AD, Bloch CA, Davis C, Snively BM, Curb D, Williams DE, Pihoker C. Family history of diabetes, autoimmunity, and risk factors for cardiovascular disease among children with diabetes in the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatr Diab 8: 354–361, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res 8: 195–202, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gorlov IP, Gorlova OY, Sunyaev SR, Spitz MR, Amos CI. Shifting paradigm of association studies: value of rare single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet 82: 100–112, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haeusler RA, Accili D. The double life of Irs. Cell Metab 8: 7–9, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kalidas K, Wasson J, Glaser B, Meyer JM, Duprat LJ, White MF, Permutt MA. Mapping of the human insulin receptor substrate-2 gene, identification of a linked polymorphic marker and linkage analysis in families with Type II diabetes: no evidence for a major susceptibility role. Diabetologia 41: 1389–1391, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J Am Stat Assoc 90: 773–795, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, Mei Z, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. CDC Growth Charts: United States. Adv Data 314: 1–27 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lautier C, El Mkadem SA, Renard E, Brun JF, Gris JC, Bringer J, Grigorescu F. Complex haplotyes of IRS2 gene are associated with severe obesity and reveal heterogeneity in the effect of gly1057asp mutation. Hum Genet 113: 34–43, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li B, Leal SM. Deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in parental and unaffected sibling genotype data. Hum Hered 67: 104–115, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liese AD, D'Agostino RB, Jr, Hamman RF, Kilgo PD, Lawrence JM, Liu LL, Loots B, Linder B, Marcovina S, Rodriguez B, Standiford D, Williams DE. The burden of diabetes mellitus among US youth: prevalence estimates from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics 118: 1510–1518, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mammarella S, Romano F, Di Valerio A, Creati B, Esposito D, Palmirotta R, Capani F, Vitullo P, Volpe G, Battista P, Della Loggia F, Mariani-Costantini R, Cama A. Interaction between the G1057D variant of IRS-2 and overweight in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Hum Mol Genet 9: 2517–2521, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudensky AS, Naylor A, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta cell function from fasting glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28: 412–419, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA 303: 242–249, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pritchard JK, Cox NJ. The allelic architecture of human disease genes: common disease–common variant… or not? Hum Mol Genet 11: 2417–2423, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schork NJ, Murray SS, Frazer KA, Topol EJ. Common vs. rare allele hypotheses for complex diseases. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19: 212–219, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sesti G, Federici M, Hribal ML, Lauro D, Sbraccia P, Lauro R. Defects of the insulin receptor substrate (IRS) system in human metabolic disorders. FASEB J 15: 2099–2111, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soria JM, Almasy L, Souto JC, Sabater-Lleal M, Pontcuberta J, Blangero J. The F7 gene and clotting factor VII levels: dissection of a human quantitative trait locus. Hum Biol 77: 561–575, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, Monda KL, Thorleifsson G, Jackson AU, Allen HL, Lindgren CM, Luan J, Magi R, Randall JC, Vedantam S, Winkler TW, Qi L, Workalemahu T, Heid IM, Steinthorsdottir V, Stringham HM, Weedon MN, Wheeler E, Wood AR, Ferreira T, Weyant RJ, Segre AV, Estrada K, Liang L, Nemesh J, Park JH, Gustafsson S, Kilpelainen TO, Yang J, Bouatia-Naji N, Esko T, Feitosa MF, Kutalik Z, Mangino M, Raychaudhuri S, Scherag A, Smith AV, Welch R, Zhao JH, Aben KK, Absher DM, Amin N, Dixon AL, Fisher E, Glazer NL, Goddard ME, Heard-Costa NL, Hoesel V, Hottenga JJ, Johansson A, Johnson T, Ketkar S, Lamina C, Li S, Moffatt MF, Myers RH, Narisu N, Perry JR, Peters MJ, Preuss M, Ripatti S, Rivadeneira F, Sandholt C, Scott LJ, Timpson NJ, Tyrer JP, van Wingerden S, Watanabe RM, White CC, Wiklund F, Barlassina C, Chasman DI, Cooper MN, Jansson JO, Lawrence RW, Pellikka N, Prokopenko I, Shi J, Thiering E, Alavere H, Alibrandi MT, Almgren P, Arnold AM, Aspelund T, Atwood LD, Balkau B, Balmforth AJ, Bennett AJ, Ben-Shlomo Y, Bergman RN, Bergmann S, Biebermann H, Blakemore AI, Boes T, Bonnycastle LL, Bornstein SR, Brown MJ, Buchanan TA, Busonero F, Campbell H, Cappuccio FP, Cavalcanti-Proenca C, Chen YD, Chen CM, Chines PS, Clarke R, Coin L, Connell J, Day IN, Heijer M, Duan J, Ebrahim S, Elliott P, Elosua R, Eiriksdottir G, Erdos MR, Eriksson JG, Facheris MF, Felix SB, Fischer-Posovszky P, Folsom AR, Friedrich N, Freimer NB, Fu M, Gaget S, Gejman PV, Geus EJ, Gieger C, Gjesing AP, Goel A, Goyette P, Grallert H, Grassler J, Greenawalt DM, Groves CJ, Gudnason V, Guiducci C, Hartikainen AL, Hassanali N, Hall AS, Havulinna AS, Hayward C, Heath AC, Hengstenberg C, Hicks AA, Hinney A, Hofman A, Homuth G, Hui J, Igl W, Iribarren C, Isomaa B, Jacobs KB, Jarick I, Jewell E, John U, Jorgensen T, Jousilahti P, Jula A, Kaakinen M, Kajantie E, Kaplan LM, Kathiresan S, Kettunen J, Kinnunen L, Knowles JW, Kolcic I, Konig IR, Koskinen S, Kovacs P, Kuusisto J, Kraft P, Kvaloy K, Laitinen J, Lantieri O, Lanzani C, Launer LJ, Lecoeur C, Lehtimaki T, Lettre G, Liu J, Lokki ML, Lorentzon M, Luben RN, Ludwig B, Manunta P, Marek D, Marre M, Martin NG, McArdle WL, McCarthy A, McKnight B, Meitinger T, Melander O, Meyre D, Midthjell K, Montgomery GW, Morken MA, Morris AP, Mulic R, Ngwa JS, Nelis M, Neville MJ, Nyholt DR, O'Donnell CJ, O'Rahilly S, Ong KK, Oostra B, Pare G, Parker AN, Perola M, Pichler I, Pietilainen KH, Platou CG, Polasek O, Pouta A, Rafelt S, Raitakari O, Rayner NW, Ridderstrale M, Rief W, Ruokonen A, Robertson NR, Rzehak P, Salomaa V, Sanders AR, Sandhu MS, Sanna S, Saramies J, Savolainen MJ, Scherag S, Schipf S, Schreiber S, Schunkert H, Silander K, Sinisalo J, Siscovick DS, Smit JH, Soranzo N, Sovio U, Stephens J, Surakka I, Swift AJ, Tammesoo ML, Tardif JC, Teder-Laving M, Teslovich TM, Thompson JR, Thomson B, Tonjes A, Tuomi T, van Meurs JB, van Ommen GJ. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet 42: 937–948, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, Morris AP, Dina C, Welch RP, Zeggini E, Huth C, Aulchenko YS, Thorleifsson G, McCulloch LJ, Ferreira T, Grallert H, Amin N, Wu G, Willer CJ, Raychaudhuri S, McCarroll SA, Langenberg C, Hofmann OM, Dupuis J, Qi L, Segre AV, van HM, Navarro P, Ardlie K, Balkau B, Benediktsson R, Bennett AJ, Blagieva R, Boerwinkle E, Bonnycastle LL, Bengtsson BK, Bravenboer B, Bumpstead S, Burtt NP, Charpentier G, Chines PS, Cornelis M, Couper DJ, Crawford G, Doney AS, Elliott KS, Elliott AL, Erdos MR, Fox CS, Franklin CS, Ganser M, Gieger C, Grarup N, Green T, Griffin S, Groves CJ, Guiducci C, Hadjadj S, Hassanali N, Herder C, Isomaa B, Jackson AU, Johnson PR, Jorgensen T, Kao WH, Klopp N, Kong A, Kraft P, Kuusisto J, Lauritzen T, Li M, Lieverse A, Lindgren CM, Lyssenko V, Marre M, Meitinger T, Midthjell K, Morken MA, Narisu N, Nilsson P, Owen KR, Payne F, Perry JR, Petersen AK, Platou C, Proenca C, Prokopenko I, Rathmann W, Rayner NW, Robertson NR, Rocheleau G, Roden M, Sampson MJ, Saxena R, Shields BM, Shrader P, Sigurdsson G, Sparso T, Strassburger K, Stringham HM, Sun Q, Swift AJ, Thorand B, Tichet J, Tuomi T, van Dam RM, van Haeften TW, van Herpt T, van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Walters GB, Weedon MN, Wijmenga C, Witteman J, Bergman RN, Cauchi S, Collins FS, Gloyn AL, Gyllensten U, Hansen T, Hide WA, Hitman GA, Hofman A, Hunter DJ, Hveem K, Laakso M, Mohlke KL, Morris AD, Palmer CN, Pramstaller PP, Rudan I, Sijbrands E, Stein LD, Tuomilehto J, Uitterlinden A, Walker M, Wareham NJ, Watanabe RM, Abecasis GR, Boehm BO, Campbell H, Daly MJ, Hattersley AT, Hu FB, Meigs JB, Pankow JS, Pedersen O, Wichmann HE, Barroso I, Florez JC, Frayling TM, Groop L, Sladek R, Thorsteinsdottir U, Wilson JF, Illig T, Froguel P, van Duijn CM, Stefansson K, Altshuler D, Boehnke M, McCarthy MI. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet 42: 579–589, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang H, Rissanen J, Miettinen R, Karkkainen P, Kekalainen P, Kuusisto J, Mykkanen L, Karhapaa P, Laakso M. New amino acid substitutions in the IRS-2 gene in Finnish and Chinese subjects with late-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 50: 1949–1951, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. White MF. The IRS-signalling system: a network of docking proteins that mediate insulin action. Mol Cell Biochem 182: 3–11, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. White MF. Regulating insulin signaling and beta-cell function through IRS proteins. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 84: 725–737, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Withers DJ, Gutierrez JS, Towery H, Burks DJ, Ren JM, Previs S, Zhang Y, Bernal D, Pons S, Shulman GI, Bonner-Weir S, White MF. Disruption of IRS-2 causes type 2 diabetes in mice. Nature 391: 900–902, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang J, Wheeler DA, Yakub I, Wei S, Sood R, Rowe W, Liu PP, Gibbs RA, Buetow KH. SNPdetector: a software tool for sensitive and accurate SNP detection. PloS Comput Biol 1: e53, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.