Abstract

Background:

The aim of this study was to review the clinicopathologic features of focal reactive gingival lesions at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria.

Methods:

A retrospective review of cases of different focal reactive gingival lesions from the records of the Departments of the Oral Biology/Oral Pathology and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital between 1970 and 2008 was carried out. Available clinical data regarding age, gender, location, estimated duration of the lesion and treatment modality were obtained and analyzed.

Results:

Prevalence rate of focal reactive gingival lesions was 5.6%. Pyogenic granuloma (PG) was the most common lesions constituting 57% of the cases. Seventeen (9.5%) of the 179 cases of PG were pregnancy induced pyogenic granuloma. The female-to-male ratio was 1.7:1. All the 4 lesions occurred more in female patients than males. The mean age of patients at presentation was 30 ± 16.5 years. The lesions were commonly seen in the second and third decade of life and least commonly seen above the age of 60 years. The lesions were equally distributed on the maxillary and mandibular gingivae, and were mostly located on the buccal gingival of the jaws. Most (51.6%) of the lesions occurred in incisors/canine region. Recurrence of the lesions was seen in 9 cases (2.9%), all pyogenic granuloma.

Conclusion:

Focal reactive gingival lesions are relatively uncommon lesions of the oral cavity with a prevalence rate of 5.6%. The lesions occurred commonly in females, and in third decades of life. Pyogenic granuloma was the most common lesions constituting 57% of all cases.

Keywords: focal, reactive, lesions, gingiva

INTRODUCTION

Oral mucosa is constantly subjected to external and internal stimuli and therefore manifests a spectrum of disease that range from developmental, reactive, and inflammatory to neoplastic.1 These lesions present as either generalized or localized lesions1. Reactive lesions are clinically and histologically non-neoplastic nodular swellings that develop in response to chronic and recurring tissue injury which stimulates an exuberant or excessive tissue response2. They may present as pyogenic granuloma, fibrous epulis, peripheral giant cell granuloma, fibroepithelial polyp, peripheral ossifying fibroma, giant cell fibroma, pregnancy epulis; and commonly manifest in the gingiva2. Such reactive lesions are less commonly present in other intraoral sites such as the cheek, tongue, palate and floor of the mouth2–8. Clinically, these reactive lesions often present diagnostic challenges because they mimic various groups of pathologic processes. They are clinically similar but possess distinct histopathological features. They may be termed ‘epulides’ when the connective tissue proliferation which occurs is confined to the gingiva9. Reactive lesions of the gingiva have been classified on the basis of their histology10–13. Kfir et al10 have specifically classified reactive gingival lesions into pyogenic granuloma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, fibrous hyperplasia and peripheral fibroma with calcification.

The aim of this study was to review the clinicopathologic features of focal reactive gingival lesions at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria and establish the relative prevalence of these lesions in relation to gender, age and site distribution and compare such with reported data in the scientific literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A review of focal reactive lesions of the gingivae presented to the Departments of Oral Pathology and Biology and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria between January 1970 and December 2008 was conducted. On the basis of the classification of reactive lesions by Kfir et al.10, the cases for inclusion in this study were those categorized as pyogenic granuloma (PG), peripheral giant cell granuloma (PGCG), peripheral fibrous hyperplasia (FH) and peripheral fibroma with calcification/peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF). Haematoxylin and eosin stained glass slides of all the aforementioned lesions were retrieved and re-evaluated according to the criteria of Daley et al.12 to confirm specific diagnosis. Clinical data regarding age, gender, location, and treatment were obtained from the patients records for each case.

Data was analysed using the SPSS for Windows (version 12.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) statistical software package; and presented in descriptive and tabular forms.

RESULTS

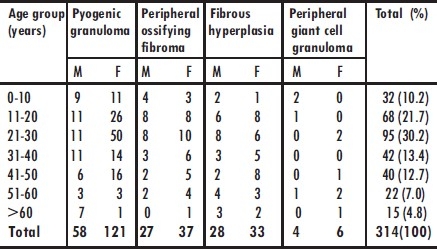

A total 314 focal reactive gingival lesions was histologically diagnosed out of a total of 5572 lesions recorded in the biopsy records during the period, with a prevalence rate of 5.6%. Pyogenic granuloma (PG) was the most common lesions constituting 57% of the cases (Figuures 1 and 2), followed by peripheral ossifying fibroma (20.4%) (Table 1, Fig. 3). Seventeen (9.5%) of the 179 cases of PG occurred in pregnancy (pregnancy induced pyogenic granuloma) There were 197 females and 117 males with a female-to-male ratio of 1.7:1.

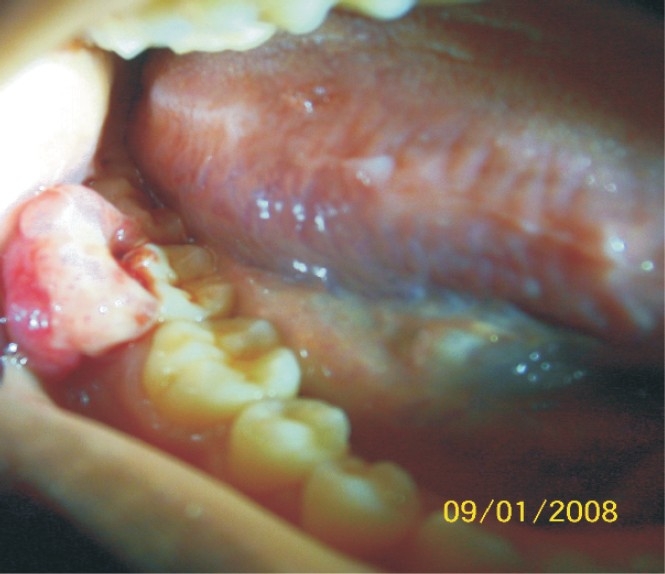

Figure 1.

Pyogenic granuloma located on the buccal gingiva of second and third lower right molars

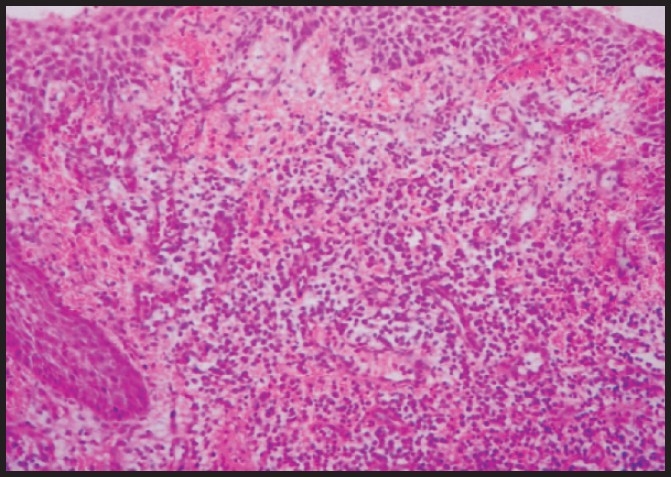

Figure 2.

Pyogenic granuloma: Photomicrograph showing dysplastic epithelium that overlies a fibrous connective tissue that contains numerous chronic inflammatory cells and blood vessels (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain × 100)

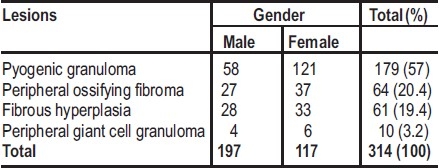

Table 1.

Distribution of focal reactive gingival lesions according to gender of patients

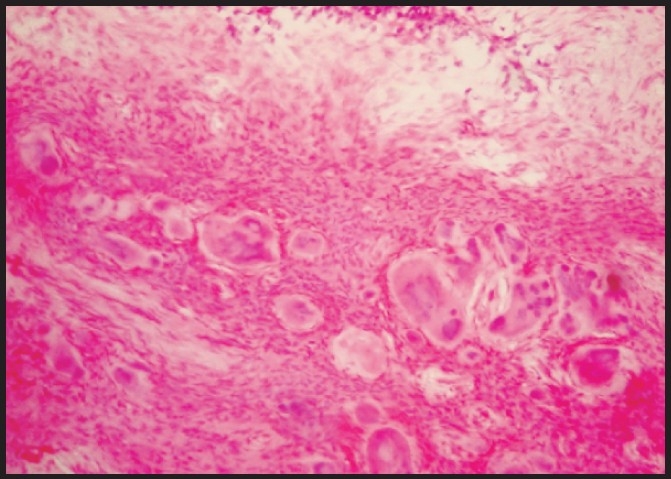

Figure 3.

Peripheral ossifying fibroma: Photomicrograph showing cellular fibrous connective tissue containing numerous calcified deposits (Hematoxylin and eosin stain ×100)

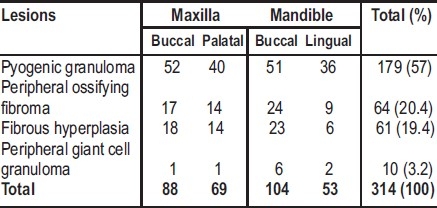

Focal reactive gingival lesion (FRGL) occurred more in females (62.7%) than males. All the 4 lesions occurred more in female patients than males (Table 1). The mean age of patients at presentation was 30 ± 16.5 years (range, 4 months to 86 years). The lesions were commonly seen in the second and third decade of life and least commonly seen above the age of 60 years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of focal reactive gingival lesions according to age group of patients

There was no significant difference in the mean age group of patients with the 4 different histologic subtypes.

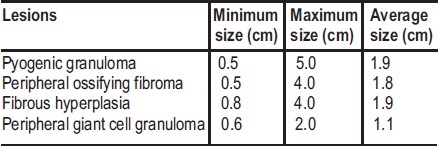

Table 3 shows the site distribution of focal reactive gingival lesions. The lesions were equally distributed on the maxillary and mandibular gingivae. The most (33.1%, n=104) common site of occurrence was mandibular bucco-labial region (Table 3). FRGL were mostly located on the buccal gingival of the maxilla and mandible. Most (51.6%, n=162) of the lesions occurred in incisors/canine region (maxilla=83, mandible=79), followed by premolar region (24.8%, n=78; maxilla=42, mandible=36) and molar region (23.6%, n=74; maxilla=32, mandible=42). Estimated duration of lesion at the time of presentation was recorded in 187 cases. This ranged from 0.25 months to 180 months with a mean of 18.3 ±30.0 months.

Table 3.

Location of focal reactive gingival lesions

Table 4 shows the average size of the lesions. Size of the lesions ranged between 0.5cm and 5cm. Radiographic findings were available in only 100 cases. No bone pathology was seen on X-ray in all cases.

Table 4.

Average size of focal reactive gingival lesions

All the lesions were surgically excised under local anaesthesia. Recurrence of the lesions was seen in 9 cases (2.9%), all pyogenic granuloma. No recurrences were recorded for the other lesions.

DISCUSSION

An extensive search of the literature showed that the present series is the largest report on the incidence of the four main histological types of focal reactive lesions of the gingiva in Lagos, Nigeria. Pyogenic granuloma was the most common lesion in the present study. Similar observations were reported in previous studies in the scientific literature11. However, another previous report showed that focal fibrous hyperplasia the most common lesion occurring14.

In the present study, all the 4 lesions were commonly seen in female patients. This is consistent with previous reports in the literature10,15. The reason for this observation is not entirely clear. However, the role of hormones, especially female hormones may need to be investigated. The exposure of inflamed gingival to progesterone and oestrogen from saliva and blood stream during pregnancy is thought to be a contributory factor in the aetiopathogenesis of pregnancy induced pyogenic granuloma6,9.

In the present study, pyogenic granuloma occurred more frequently in the third decade of life, in females (female-to-male ratio of 2.1: 1), and in the anterior region of the jaws. Similar findings were reported by Vilman et al16. Poor oral hygiene has been reported to be a precipitating factor in the development of pyogenic granuloma17. Pyogenic granuloma of the gingiva has been reported to develop in up to 5% of pregnancies18.

In this study, 9.5% of cases of pyogenic granuloma appeared to be pregnancy induced. Reports from previous studies suggested that female gender predilection and third decade age incidence observed for PG, reflected the influence of pregnancy in its pathogenesis10,15. Daley et al19 reported a positive relationship between PG and serum estrogen and progesterone concentrations in pregnant women. They suggested that these hormones render the gingival tissues more susceptible to chronic irritation by calculus and plaque, and ultimately leading to development of pregnancy-associated pyogenic granuloma. The increased prevalence of PG towards the end of pregnancy and its shrinkage tendency post partum indicate the hormonal role in its aetiology20,21. The gradual rise in the development of PG through out pregnancy may be due to the increasing levels of estrogen and progesterone that occurs as pregnancy progresses20,21. The return of the hormonal levels to normal post partum usually occurs with resolution of PG in some cases even without treatment22.

Pyogenic granulomas are highly vascular in appearance and often bleed easily due to their extreme vascularity. Microscopic examination of PG usually shows an ulcerated surface epithelium that overlies a connective tissue which contains numerous small and large endothelium lined channels that are engorged with red blood cells. In addition, a mixture of inflammatory cell infiltrate is usually present within the connective tissue stroma.

Certain factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor23, connective tissue growth factor24,25 and basic fibroblast growth factor24 have been implicated in the rapid growth and angiogenesis of pyogenic granuloma. Estrogen has been shown to cause granulation tissue formation by stimulating basic fibroblast growth factor (b FGF) and transforming growth factor β1 (TGF- β1) in fibroblasts26. Recent studies have shown that the enhancing effect of estrogen on macrophages to produce vascular endothelial growth factor is antagonized by androgens and may therefore be related to the development of PG during pregnancy27. Ojanotko-Harri et al28 suggested that progesterone acts as an immunosuppressant in the gingival tissues in pregnant women by preventing the development of a rapid acute inflammatory reaction against plaque but allowing an increased chronic tissue reaction that results clinically in an exaggerated appearance of inflammation.

The validity of the term ‘pregnancy epulis or tumour’ is questionable. Some authors believe that term ‘pregnancy epulis simply represents a PG that occurs in pregnancy due to marked similarities in the clinical and histological appearance of both lesions22,29. Others believe that pregnancy tumour or epulis has a unique nature due to the influence of progesterone and estrogen and should be considered a separate entity19. On the basis of the extreme similar clinical presentation and histological appearance of PG and PG in pregnancy (pregnancy epulis) observed in our series, we believe that pregnancy epulis simply represents a pyogenic granuloma.

Peripheral fibroma with calcification (peripheral ossifying fibroma) occurred more frequently in females than in males in our series by a ratio of 1.4:1. There was bimodal peak age of incidence at the 2 nd and 3rd decades of life followed by a definite decline showing that POF has a marked predilection for the younger age group. This finding is consistent with reports from previous studies3,10,14. Eversole and Rovin30 indicated that the loss of periodontium which occurs with tooth loss in old age could explain the greater occurrence of POF in the younger age group. Furthermore they suggested that the strict gingival site location of POF supports a superficial periodontal ligament histogenic derivation. The periodontal ligament contains cells capable of producing cementum and bone and this explains the presence of bone or cementum in POF.

Peripheral giant cell granuloma an exophytic lesion, clinically similar to but histologically different from PG due the presence of numerous multinucleated giant cells is strictly seen in the gingiva. Its strict gingival location, as in the case of POF, also supports a possible histogenic derivation from superficial periodontal ligament31. The present study reports a wide age distribution of PGCG which agrees with reports from the scientific literature11,13. In addition PGCG appears to have a mandibular site predilection particularly in the buccal posterior region. This finding was in agreement with reports from previous studies3,11,31. Although Kfir et al10 reports no sex predilection for PGCG, we observe a female preponderance in our series. This agrees with observations from study that was conducted to establish the prevalence of 636 different reactive gingival lesions in an Iraqi community11.

A substantial overlap exists between the various histological types of reactive focal gingival hyperplastic lesions. The frequent gingival site occurrence supports an assertion that these hyperplastic lesions are the same lesions at different developmental stages22,29. Daley et al12 suggested that the vascular component of PG is gradually replaced by fibrous tissue with time and, hence, diagnosed as a fibrous hyperplasia or fibroma. In addition, Natheer Al- Rawi11 observed that fibrous hyperplasia on the gingiva not only have the same female gender preponderance but occur in the same age group and site as gingival pyogenic granuloma. An inference that fibrous hyperplasia represents a fibrous maturation of pyogenic granuloma especially in lesions with long duration was therefore made to support the assertion. On the contrary, our study did not show a clear-cut age grouping for the various histologic entities. The mean ages for the different lesions was not shown to distinctly reflect the progressive development of the lesions through the different histological stages, therefore whether or not the focal reactive gingival lesions represent the same lesion at different developmental stages is questionable.

Identification of any reactive hyperplastic gingival lesion requires the formulation of a differential diagnosis to enable accurate patient evaluation and management. These lesions must be separated clinically and histologically from precancerous, developmental and neoplastic lesions. Differential diagnoses include metastatic tumours in the oral cavity, angiosarcomas, gingival non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, Kaposi's sarcoma and haemangioma. Metastatic lesions in the oral cavity may be the first indication of an undiscovered malignancy at a distant site32. The clinical appearance of these lesions in most cases has a striking resemblance to reactive gingival lesions most especially pyogenic granuloma. In addition, the clinical appearance of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the gingiva may also be an asymptomatic reactive gingival lesion32. Small haemangiomas may also be clinically indistinguishable from PG26.

CONCLUSION

A substantial overlap exists between the various histological types of focal reactive gingival hyperplastic lesions. Focal reactive gingival lesions are relative uncommon lesions of the oral cavity with a prevalence rate of 5.6%. The lesions occurred commonly in females, and in third decades of life. Pyogenic granuloma was the most common lesions constituting 57% of all cases. The lesions were equally distributed on the maxillary and mandibular gingivae especially on the buccal region of incisor/canine region. Recurrence following surgical excision was low.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott JH, Symons NBB. 9th edition. London Melbourne and New York: Churchill Livingston Edinburgh; 1982. Introduction to dental anatomy. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shenoy SS, Dinkar AD. Pyogenic granuloma associated with bone loss in an eight year old child. A case report. J Indian Soc Ped and Prev Dent. 2006;24:201–3. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.28078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchner A, Calderon S, Ramon Y. Localized hyperplastic lesions of the gingival: a clinicopathological study of 302 lesions. J Periodontol. 1977;93:305–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stablien MJ, Silverglade LB. Comparative analysis of biopsy specimens from gingival and alveolar mucosa. J. Periodontol. 1985;56(11):671–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.11.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarei MR, Chamani G, Amanpoor S. Reactive hyperplasia of the oral cavity in Kerman province, Iran : a review of 172 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45(4):288–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell JL, Bailey CL, Coopland AT, Otis CN, Frank JL, Meyer I. Nd:yag laser excision of a giant gingival pyogenic granuloma of pregnancy. Lasers Surg Med. 1994;14:178–83. doi: 10.1002/1096-9101(1994)14:2<178::aid-lsm1900140211>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White JM, Chaudhry SL, Kudler JJ, Sekandari N, Schoelch ML, Silverman S., Jr Nd :YAG and Co2 laser therapy of oral mucosal lesions. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1998;16:299–304. doi: 10.1089/clm.1998.16.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assadat M, Pour H, Rand M, Mojtahedi A. A survey of soft tissue tumour –like lesions of oral cavity: a clinicopathological study. Iranian Journal of Pathology. 2008;3(2):81–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee KW. The fibrous epulis and related lesions.Granuloma pyogenicum. Pregnancy tumour, fibroepithelial polyp and calcifying fibroblastic granuloma. A clinic pathological study. Periodontics. 1968;6:277–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kfir Y, Buchner A, Hansen LS. Reactive lesions of the gingiva. A clinico-pathological study of 741 cases. J Periodontol. 1980;51:655–61. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.11.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natheer Al-Rawi H. Localized reactive hyperplastic lesions of the gingiva: a clinico- pathological study of 636 lesions in Iraq. Internet Journal of Dental Science. 2009;7:1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daley TD, Wysocki GP, Wysocki PD, Wysocki DM. The major epulides: Clinico- pathological correlations. J Can Dent Assoc. 1990;56:627–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bataineh A, Al-Dowairi ZN. A survey of localized lesions of oral tissues. A clinic pathological study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nartey NO, Mosadomr HA, Al-Cailani M, Al -Mobeerik A. Localized inflammatory hyperplasia of the oral cavity: clinic-pathological study of 164 cases. Saudi Dent J. 1994;6:145–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angelopoulous AP. Pyogenic granuloma of the oral cavity: statistical analysis of its clinical features. J Oral Surg. 1971;29:840–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vilmann A, Vilmann P, Vilmamm H. Pyogenic granuloma evaluation of oral conditions. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:376–82. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. 4th edition. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2003. Oral Pathology: Clinical pathologic considerations; pp. 115–116. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sills ES, Zegarelli DJ, Hoschander MM, Strider WE. Clinical diagnosis and management of hormonally responsive oral pregnancy tumour (pyogenic granuloma) J Reprod Med. 996;41:467–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daley TD, Nartey NO, Wysocki G P. Pregnancy tumour an analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1991;72:196–99. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg MS, Glick M. 10th edition. Hamilton: BC Decker; 2003. Burket's Oral Medicine Diagnosis and treatment; pp. 141–142. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonis ST, Fazio RC, Fang LST. 2nd edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996. Principles and practice of Oral Medicine; p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neville BW, Damn DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology; pp. 518–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bragado R, Bello E, Requena L, Renedo G, Texeiro E, Alvarez MV, Castilla MA, Caramelo C. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in pyogenic granuloms. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1990;79:422–25. doi: 10.1080/000155599750009834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Igarashi A, Hayashi N, Nashiro K, Takehara K. Differential expression of connective tissue growth factor gene in cutaneous fibrohistiocytic and vascular tumours. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:143–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1998.tb01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagiwara K, Khaskhely NM, Uezato H, Nonaka S. Mast cell ‘densities’ in vascular proliferations. A preliminary study of pyogenic granuloma, portwine stains carvernous hemangiomas, cherry angiomas, Kaposi's sarcoma and malignant hemangio-endothelioma. J Dermatol. 1999;26:577–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48(4):167–75. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.48.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanda N, Watanabe S. Regulatory roles of sex hormones in cutaneous biology and immunology. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;38:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ojanotko-Harri AO, Harri MP, Hurttia HM, Sewon LA. Altered tissue metabolism of progesterone in pregnancy gingivitis and granuloma. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:262–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM, Tomich CE. 4th edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1983. A textbook of Oral Pathology; pp. 359–40. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eversole LR, Rovin S. Reactive lesions of the gingiva. J Oral Pathol. 1972;1:30–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooke BED. The fibrous epulis and the fibroepithelial polyp: their histogenesis and natural history. Br Dent J. 1952;93:305–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirshberg A, Buchner A. Metastatic tumours of the oral region. An overview. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1995;31:355–36. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]