An activator of RAC/ROP GTPases, RopGEF7, regulates the maintenance of the root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis by mediating the expression of PLETHORA transcription factors and interacting with At RAC1 to activate RAC/ROP signaling. RopGEF7 expression is stimulated by auxin and may be an integral component of a network that regulates auxin signaling and root development.

Abstract

The root stem cell niche defines the area that specifies and maintains the stem cells and is essential for the maintenance of root growth. Here, we characterize and examine the functional role of a quiescent center (QC)–expressed RAC/ROP GTPase activator, RopGEF7, in Arabidopsis thaliana. We show that RopGEF7 interacts with At RAC1 and overexpression of a C-terminally truncated constitutively active RopGEF7 (RopGEF7ΔC) activates RAC/ROP GTPases. Knockdown of RopGEF7 by RNA interference causes defects in embryo patterning and maintenance of the QC and leads to postembryonic loss of root stem cell population. Gene expression studies indicate that RopGEF7 is required for root meristem maintenance as it regulates the expression of PLETHORA1 (PLT1) and PLT2, which are key transcription factors that mediate the patterning of the root stem cell niche. Genetic analyses show that RopGEF7 interacts with PLT genes to regulate QC maintenance. Moreover, RopGEF7 is induced transcriptionally by auxin while its function is required for the expression of the auxin efflux protein PIN1 and maintenance of normal auxin maxima in embryos and seedling roots. These results suggest that RopGEF7 may integrate auxin-derived positional information in a feed-forward mechanism, regulating PLT transcription factors and thereby controlling the maintenance of root stem cell niches.

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells in the root meristem (RM) provide the source of cells for the generation of different tissues that form the root of higher plants. Root growth is achieved by the balance of two processes: the maintenance of stem cells surrounding a group of mitotically inactive cells called the quiescent center (QC) and the formation of differentiated cell types (Jiang and Feldman, 2005; Scheres, 2007). In Arabidopsis thaliana, maintenance of the root stem cells requires the activity of the QC (van den Berg et al., 1997), which together with its surrounding stem cells forms a stem cell niche (Aida et al., 2004). The root stem cell niche is established during embryogenesis and serves as the source for postembryonic root development (Weigel and Jürgens, 2002; Aida et al., 2004). The specification of the root stem cell niche requires two parallel, transcriptionally regulated pathways: an auxin-dependent PLETHORA (PLT)-regulated (Aida et al., 2004; Blilou et al., 2005) and an auxin-independent SHORTROOT (SHR) and SCARECROW (SCR)-regulated pathway (Helariutta et al., 2000; Sabatini et al., 2003). The PLT gene family encodes several AP2-type transcription factors that are essential for stem cell niche maintenance. Ectopic expression of PLT genes induced QC, stem cell, and RM formation in the hypocotyl and shoots, thus identifying the PLT transcription factors as master regulators of root development (Aida et al., 2004; Galinha et al., 2007).

PLT expression is regulated by auxin and dependent on auxin response factors (Aida et al., 2004). PLT genes have been shown to have a gradient of expression in the root, which is thought to be outputs of an underlying auxin gradient (Galinha et al., 2007; Grieneisen et al., 2007). Regulation of the PLT gradient in root development apparently involves novel mechanisms that are yet to be fully understood. For instance, GCN5 (for general control nonderepressible 5), a histone acetyltransferase important for chromatin modification in postembryonic root stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis (Kornet and Scheres, 2009), genetically interacts with TOPLESS (TPL), an IAA12-interacting transcriptional corepressor. TPL acts directly at the PLT1 and PLT2 promoter, and the tpl loss-of-function mutant has been shown to display ectopic PLT activity and apical root formation (Long et al., 2006; Szemenyei et al., 2008; Smith and Long, 2010). Furthermore, recent reports also identified a critical role for tyrosylprotein sulfotransferases and their substrate root growth factors as peptide hormones in root stem cell niche maintenance (Komori et al., 2009; Matsuzaki et al., 2010), and tyrosylprotein sulfotransferases have been shown to function through the auxin-mediated PLT pathway (Zhou et al., 2010). However, the identity of additional signaling components involved in regulating the PLT gradient is not known.

RAC/ROP GTPases form a plant-specific clade of the conserved RHO family of small GTPases (Yang and Fu, 2007; Fowler, 2010). They regulate a wide range of signaling pathways in plants, affecting polarized cell growth of pollen tubes and root hairs, leaf epidermal cell morphogenesis, pathogen defense and oxidative stress–related responses, and hormone responses, such as those for auxin and abscisic acid (reviewed in Nibau et al., 2006; Yalovsky et al., 2008; Yang, 2008; Wu et al., 2011). Report of a pea (Pisum sativum) Rop1-related protein in CLAVATA signaling implicates a potential role for RAC/ROP signaling in meristem development (Trotochaud et al., 1999). Recently, a RAC/ROP effector, ICR1 (for interactor of constitutive active ROPs 1), has been shown to affect embryo patterning and RM maintenance. Loss of ICR1 function resulted in embryo defects and collapse of the RM in icr1 mutants as a result of altered polar localization of auxin efflux transporters (i.e., PIN proteins) at the plasma membrane, thus affecting auxin distribution (Lavy et al., 2007; Hazak et al., 2010). Molecular mechanisms underlying RAC/ROP-regulated meristem development remain to be elucidated.

As with their RHO GTPase counterparts in animals and yeast, RAC/ROPs are pivotal signaling switches that cycle between their GTP-bound active and GDP-bound inactive forms. The cycling of GTP- and GDP-bound small G proteins is regulated by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs). GAPs accelerate GTP hydrolysis, converting them back to the inactive GDP-bound form and terminating signaling from these GTPases. Guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors also negatively regulate these small G proteins by sequestering them in the cytosol, although they also participate in recycling the inactive GTPases through the cytosol, delivering them to the cell membrane for functioning (Klahre et al., 2006). GAPs and guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors for RAC/ROPs have been identified in plants (Bischoff et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2000).

GEFs promote small G protein activation by stimulating the exchange of GDP for GTP. RAC/ROPs use predominantly a plant-specific family of GEFs named RopGEFs for activation (Berken et al., 2005). RopGEFs share a conserved PRONE domain for GEF catalytic activity but have variable N- and C-terminal domains. There are 14 RopGEFs in the Arabidopsis genome. Overexpression analysis in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and Arabidopsis pollen tubes suggest a subset of these RopGEFs are involved in regulating tip growth (Gu et al., 2006; Zhang and McCormick, 2007; Cheung et al., 2008), but their biological roles in growth and development remain to be revealed. Involvement of RopGEFs in receptor-like kinase (RLK)–mediated signaling has been suggested by studies on the mechanisms of pollen tube growth and root hair development. A highly phosphorylated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) kinase partner protein is a RopGEF that interacts with a pollen-specific RLK, PRK1, in vivo (Kaothien et al., 2005). In Arabidopsis, RopGEF12 interacts with a pollen receptor kinase, PRK2a, through its C terminus. Coexpression of RopGEF12 and PRK2a in tobacco pollen tubes led to depolarized tip growth similar to that induced by overexpression of a constitutively active ROP (Zhang and McCormick, 2007). Additionally, members of the Catharanthus roseus RLK-related family (Kessler et al., 2010; Nibau and Cheung, 2011) have been identified as upstream regulators for RopGEFs in a yeast two-hybrid screen, and loss of function in one of these, the FERONIA receptor-like kinase, results in reduced levels of active RAC/ROPs and severe root hair defects (Duan et al., 2010).

Here, we examine the biological role of RopGEF7 and show that RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown of its expression resulted in transgenic progeny with RM defects. We provide molecular and genetic evidence that RopGEF7 is specifically expressed in the QC precursor during embryogenesis and in the QC of postembryonic root and modulates root stem cell maintenance by regulating the expression of PLT genes. Furthermore, we show that auxin stimulates expression of RopGEF7, which in turn is required for the expression of the auxin efflux protein PIN1 and affects auxin-induced reporter gene expression at the root tip region. Taken together, these results implicate RopGEF7 in a feed-forward mechanism connecting RopGEF-regulated RAC/ROP signaling and auxin-dependent PLT-regulated root pattern formation.

RESULTS

RopGEF7 Expression Is Restricted to the QC Precursor Cells during Embryogenesis and Extends to Broader Tissue Types in Postembryonic Development

To assess the possible role of RopGEF7 in plant development, the promoter-GUS (β-glucuronidase) fusion gene (RopGEF7pro::GUS) was used to study the RopGEF7 gene expression pattern. Analysis of several RopGEF7pro:GUS transgenic lines revealed that GUS activity was specifically restricted to the precursor cells of the QC at the heart, torpedo, bent-cotyledon, and mature embryo stages during embryogenesis (Figures 1A to 1D). At the seedling stage, RopGEF7 expression remained most predominant in the QC (Figure 1E) but expanded to the vascular bundles of root differentiated zones and lateral root primordia (Figures 1F and 1G). RopGEF7 expression was also detected in the vasculature of hypocotyls, in the meristemoid and guard cells of cotyledons (see Supplemental Figures 1A and 1B online), and in the styles of the flowers (see Supplemental Figure 1C online). QC expression of RopGEF7 is consistent with the results from the QC transcriptional profile analysis (Nawy et al., 2005).

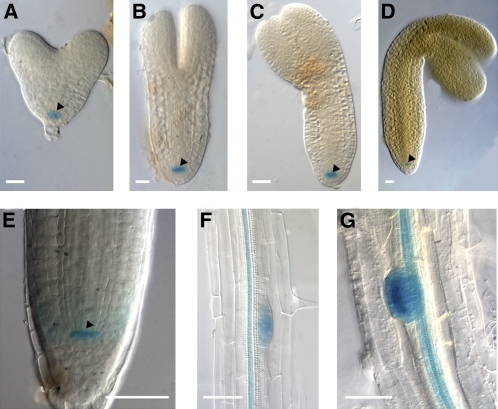

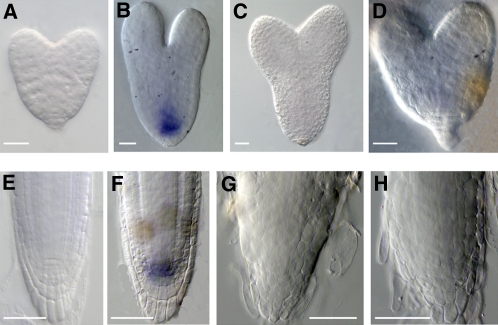

Figure 1.

RopGEF7 Expression Profile Analysis during Embryogenesis and Seedling Root Development.

(A) to (D) Detection of RopGEF7pro:GUS expression in the precursor cells of the QC at the heart (A), torpedo (B), bent cotyledon (C), and mature (D) embryo stages. GUS staining was for 16 h.

(E) to (G) Detection of GUS activity in a 5-d-old RopGEF7pro:GUS seedling in the QC of a primary root tip (E), mature zone of a primary root (F), and lateral root primordia (G). GUS staining was for 6 h.

Arrowheads indicate the QC. Bars =20 μm in (A) to (D) and 50 μm in (E) to (G).

RNAi Knockdown of RopGEF7 Induces Patterning and QC Maintenance Defects during Embryogenesis

The RopGEF7 expression pattern suggests that this gene may be functionally important for embryogenesis. Since potential null mutants for RopGEF7 could not be identified from T-DNA insertion mutants listed in Arabidopsis databases, an RNAi approach was used to study the function of RopGEF7. To examine more precisely the role of RopGEF7 in embryo development, a strong embryonic promoter, RPS5A (Weijers et al., 2001), was used to control the expression of RopGEF7RNAi. In total, 55 T1 independent RPS5Apro:RopGEF7RNAi transformed lines were obtained. The progeny from 45 of these plants suggested embryo defects. Transcript analysis of a subset of these RNAi lines (see Supplemental Figure 2A online) showed that their embryo defects correlated with reduced levels of RopGEF7 expression and that the transgenic line that produced the lowest amount of RopGEF7 mRNA, L6, had the highest percentage of embryo defects. The expression level of RopGEF1, a closely related homolog of RopGEF7, was not affected in L6 (see Supplemental Figure 2B online), suggesting minimum off-target silencing and consistent with RNAi being targeted to a relatively diverse region among RopGEFs. Thus, L6 was chosen for subsequent analysis.

The most striking and commonly observed phenotype among RPS5Apro:GEF7RNAi transgenic seedlings was related to the development of the precursor of the RM during embryogenesis. At the heart stage, nearly 19.2% of embryos analyzed (n = 156) exhibited abnormal morphogenesis in the basal pole of embryos (see Supplemental Table 2 online). The hypophysis region in wild-type embryos (n = 127) shows its normal pattern with two layers of cells, and each layer has two cells (Figures 2A and 2B; see Supplemental Table 2 online): the upper lens-shaped cell has already divided, producing two cells that will develop into the QC of the RM, while the lower layer will form the single layer of the columella stem cells. In RopGEF7RNAi embryos, the hypophysis region either showed aberrant cell plate formation, leading to disorganization in the basal embryo region (Figure 2D), or it formed two layers of progenitor cells for the QC and the columella initials accompanied by additional, abnormal divisions (Figure 2E). In some cases, the cell division defect in the hypophyseal region of these RopGEF7RNAi embryos was also accompanied by periclinal divisions of suspensor cells (Figures 2F and 2G), whereas the wild-type suspensor cells divided anticlinally at this stage (Figure 2B). The division defect of the hypophyseal cell region in these RopGEF7 knockdown embryos persisted throughout the late heart stage (Figures 2C, 2H, and 2I). Embryos from 35Spro:RopGEF7RNAi plants (Figure 3A; see Supplemental Figures 3A to 3C online) also displayed a similar embryo phenotype (see Supplemental Figures 3D and 3E online) to those observed for RPS5Apro:RopGEF7RNAi. The basal embryo defects in these RopGEF7 RNAi plants resemble those observed in plt1 plt2 double mutants, plt1 plt3 bbm triple mutants, and pin4 (Friml et al., 2002; Aida et al., 2004; Galinha et al., 2007).

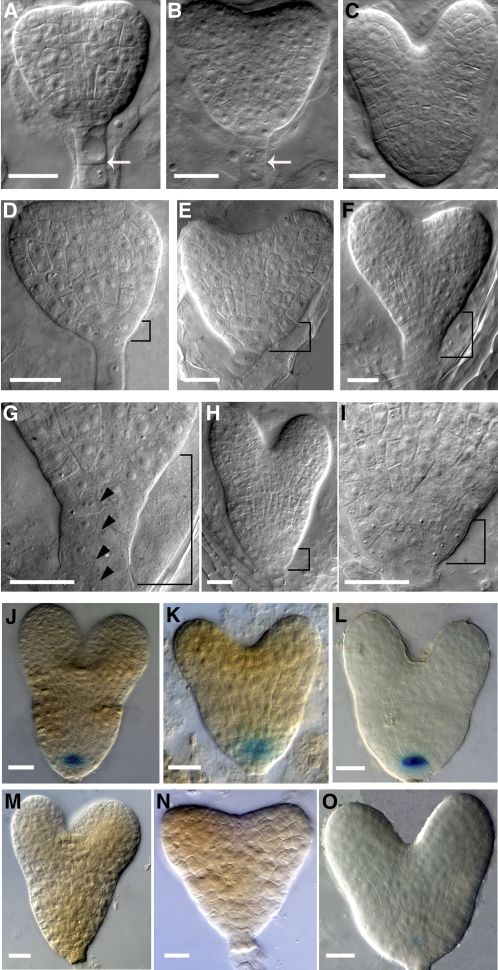

Figure 2.

Downregulation of RopGEF7 during Embryogenesis Induces Defects in Cell Division and Maintenance of the QC.

(A) to (C) Wild-type embryos in early heart (A), heart (B), and late heart (C) stages. Arrows indicate the anticlinal cell division in suspensor cells.

(D) to (I) Basal cell division defects in RPS5Apro:RopGEF7 RNAi embryos at the early heart (D), heart ([E] and [F]), and late heart (H) stages. (G) and (I) show magnifications of basal cell regions (bracketed) in (F) and (H), respectively. Arrowheads point to periclinal cell divisions in suspensor cells.

(J) to (L) GUS staining of QC25:GUS (J), QC46:GUS (K), and RopGEF7pro:GUS (L) in a control embryo.

(M) to (O) GUS staining of QC25:GUS (M), QC46:GUS (N), and RopGEF7pro:GUS (O) in an RNAi embryo.

Bars = 20 μm in (A) to (O).

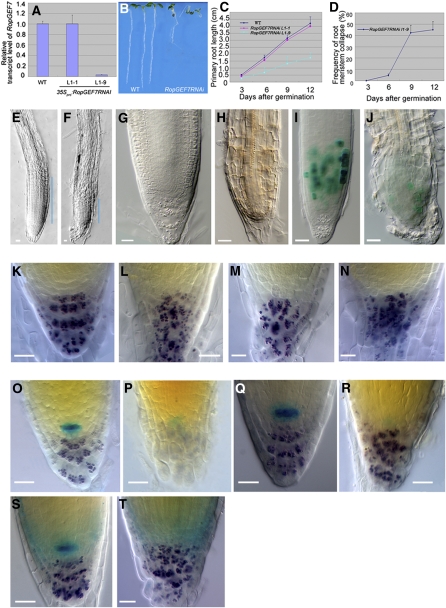

Figure 3.

RopGEF7 Is Important for Root Stem Cell Maintenance.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of RopGEF7 expression in 7-d-old wild-type and RopGEF7 RNAi transgenic lines (L1-1 and L1-9).

(B) Phenotype of 5-d-old seedlings of the wild type and RopGEF7RNAi (from left to right).

(C) and (D) Root length (C) and meristem collapse frequency (D) at different time points for the wild type and RopGEF7RNAi. In each experiment, a total of 30 to 50 plants was used for measurement. Data presented in (D) are the averages from three biological repeats with sd and with 50 plants in each repeat.

(E) and (F) Three-day-old root tips of the wild type (E) and RopGEF7RNAi (F). Blue lines indicate the RM region.

(G) and (H) Nine-day-old root tips of the wild type (G) and RopGEF7RNAi (H).

(I) and (J) Cyclin B1;1:GUS expression in 5-d-old root tips of the wild type (I) and RopGEF7RNAi (J).

(K) to (N) Distal RM region of 5-d-old seedling of the wild type (K) and RopGEF7RNAi ([L] to [N]). Starch granule staining labels the differentiated cells in the columella (purple).

(O) and (P) Double staining of QC25:GUS marker and starch granules (purple) in 5-d-old wild-type (O) and RopGEF7RNAi (P) seedlings.

(Q) and (R) Double staining of QC46:GUS marker and starch granules in 5-d-old root tips of wild-type (Q) and RopGEF7RNAi (R) seedlings.

(S) and (T) Double staining of RopGEF7pro:GUS marker and starch granules in 5-d-old root tips of wild-type (S) and RopGEF7RNAi (T) seedlings.

Bars = 20 μm in (E) to (T).

Defects in embryogenesis were also observed prior to the heart stage in ~4.8% of the RPS5Apro:RopGEF7RNAi embryos examined (n = 332; see Supplemental Table 2 online). At the 8-cell stage, abnormal cell division pattern in apical development was detected in these RopGEF7RNAi embryos (see Supplemental Figures 2G to 2H compared with 2C online). At the 16-cell, 32-cell, and globular stages, the defective embryos exhibited abnormal morphology in both apical and basal embryo regions (see Supplemental Figures 2I to 2K compared with 2D to 2F online). Due to these aberrant cell divisions, the presumptive hypophyseal cell region was not properly defined and the apical embryos were also misshaped. Collectively, the embryo phenotypes in RopGEF7RNAi plants indicate that RopGEF7 function is important for embryo patterning, and, especially, the basal embryonic defects at the heart stages reflect that RopGEF7 can affect the specification of the QC and its surrounding stem cells.

To gain further insight into cell identities in RopGEF7RNAi embryonic stem cell regions, we analyzed expression patterns of QC-specific markers, including RopGEF7pro:GUS. In the wild type, QC25 and QC46 were expressed in the QC precursor cell at the heart-stage embryos (100%, n = 30; Figures 2J and 2K). On the other hand, the corresponding cells in RopGEF7RNAi embryos showed no detectable expression (90 to 95%, n = 16 to 25; Figures 2M and 2N) or reduced expression (5 to 10%, n = 16 to 25). RopGEF7pro:GUS is readily detected in the QC precursor cells in the wild-type heart-stage embryos (100%, n = 30; Figure 2L), whereas its expression is substantially suppressed in RopGEF7RNAi (100%, n = 22; Figure 2O). It is evident from our results that some features of the RopGEF7RNAi embryo phenotype, including disorganized cell division in the hypophysis region, correlate with RopGEF7 expression in QC precursor cells of heart stage embryos. This finding supports a role for RopGEF7 in the establishment and maintenance of embryonic cell division patterns and the QC.

Downregulation of RopGEF7 Affects Stem Cell Maintenance in the RM

To investigate the postembryonic function of RopGEF7, we focused on several 35S-RopGEF7RNAi transformed lines with reduced RopGEF7 mRNA levels (Figure 3A; see Supplemental Figure 3A online). Two lines, L1-9 and L1-1 with strongly suppressed and almost normal levels of RopGEF7 mRNA (Figure 3A), respectively, were selected for further analysis. Downregulation of RopGEF7 suppressed root growth. The RNAi seedlings developed shorter roots (Figure 3B; see Supplemental Figure 3B online), with L1-9 showing the most significantly reduced root growth rate compared with the wild type and L1-1 transgenic line (Figure 3C). The RM size in L1-9 was also reduced (cf. Figures 3E and 3F). Nine days after germination, RM cells were completely differentiated in 42.3% of the L1-9 plants (cf. Figures 3D and 3H with 3G). To assess whether the reduction in meristem size could be due to reduced cell division in the RM region, we visualized RM cells by expressing D-Box Cyclin B1;1pro:GUS (Colón-Carmona et al., 1999), a reporter gene for the G2-M phase in the cell cycle. There were notably fewer GUS-expressing cells in the RNAi RM than in wild-type seedlings (cf. Figure 3J with 3I), consistent with cell division being suppressed in the RM region of these RopGEF7 RNAi plants. Moreover, the wild-type root cap has an ordered structure, which consists of a layer of columella stem cells and four layers of columella cells (Figure 3K). On the other hand, RNAi roots displayed disorganized columella tiers (Figures 3L to 3N).

To examine whether the decrease in RM size observed in the RopGEF7RNAi plants correlated with their defects in QC maintenance, we analyzed the expression of the QC-specific reporters QC25:GUS and QC46:GUS along with that of RopGEF7pro:GUS. The wild-type roots expressed QC25 and QC46 in QC cells (100%, n = 30; Figures 3O and 3Q). By contrast, expression of QC25 was reduced in 91.4% of RNAi roots (n = 35, Figure 3P) or completely missing in 8.6% of RNAi roots (n = 35) compared with the wild type. Similarly, QC46 expression was also suppressed (80%, n = 30; Figure 3R) or missing in RNAi roots (20%, n = 30). The peak activity of RopGEF7pro:GUS was detected in the QC in all the wild-type seedlings examined (n = 30; Figure 3S), but the activity in the QC was entirely absent from RNAi roots (n = 16; Figure 3T). These results suggest that RopGEF7 is required for the maintenance of the root organizing center and thereby affects the maintenance of the RM stem cells.

RopGEF7 Interacts with and Activates RAC/ROPs

Members of the Arabidopsis RopGEF family were identified as activators of ROP/RACs by biochemical and structural studies (Berken et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2006; Thomas et al., 2007). To determine the functional relationship between RopGEF7 and RAC/ROPs, we first examined the physical interaction between RopGEF7 and At RAC1 by bimolecular fluorescence complement (BiFC) assays in plant cells. Since the variable C-terminal domain of some RopGEFs has been shown to autoinhibit GEF activity (Gu et al., 2006; Zhang and McCormick, 2007), we constructed both the full-length and C terminus truncated, constitutively active RopGEF7 (RopGEF7ΔC) vectors for BiFC assays. When BiFC constructs of RopGEF7 or RopGEF7ΔC and At RAC1 were cotransformed into Arabidopsis protoplasts, BiFC-generated yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) signal was observed (Figures 4B and 4C), whereas the controls showed background signal (Figures 4A), indicating that both RopGEF7 and RopGEF7ΔC interacted with At RAC1 in Arabidopsis protoplasts. We also examined the expression of YFP-tagged At RAC1, RopGEF7, and RopGEF7ΔC individually in protoplasts. At RAC1 displayed predominant association with the plasma membrane (Figure 4D), whereas RopGEF7 and RopGEF7ΔC partitioned between the plasma membrane and cytosol (Figures 4E and 4F), similar to the pattern seen in Figures 4B and 4C. We then examined whether RopGEF7 directly regulates the activity of RAC/ROPs by protein binding domain (PBD) pull-down assays that specifically target activated RAC/ROPs (Tao et al., 2002). As shown in Figure 4G, the levels of GTP-bound active form of RAC/ROPs in one RopGEF7ΔC overexpressing line, L34 (Figure 5A), as detected by anti-NtRac1 antibody (Tao et al., 2002) were remarkably increased. Therefore, these results are consistent with RopGEF7 interacting with RAC/ROPs, and activating them to regulate downstream signaling pathways.

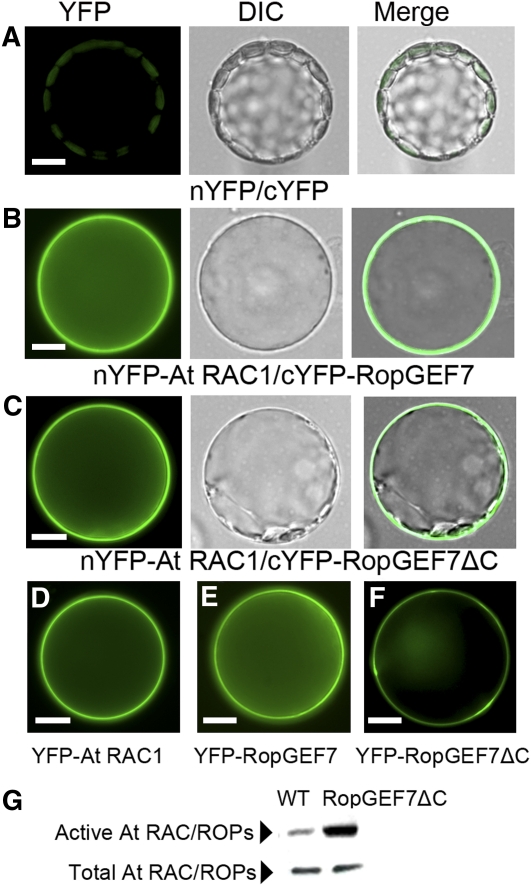

Figure 4.

RopGEF7 Interacts with and Activates At RAC/ROPs.

(A) to (C) Arabidopsis protoplasts were cotransfected with N-terminal YFP and C-terminal YFP (A), nYFP-At RAC1 and cYFP-RopGEF7 (B), and nYFP-At RAC1 and cYFP-GEF7ΔC (C). Images are acquired under the YFP and differential interference contrast (DIC) channel, respectively, and then merged together.

(D) to (F) Localization of YFP-labeled At RAC1 (D), RopGEF7 (E), and GEF7ΔC (F).

(G) GST-PBD pull-down assays for active At RACs in wild-type seedlings and RPS5Apro:RopGEF7ΔC-overexpressing line L34 (top panel). Bottom panel shows total At RAC/ROPs (active and inactive) from the corresponding samples. Nt Rac1 antibody was used against At RAC/ROP proteins.

Bars = 10 μm in (A) to (F).

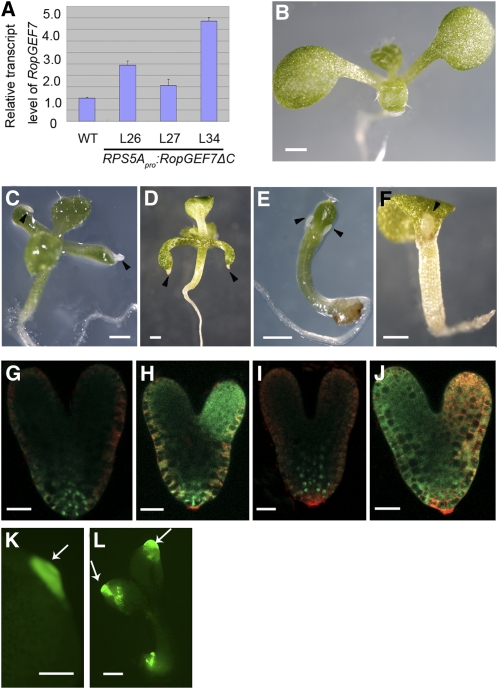

Figure 5.

Upregulation of RAC/ROP Signaling Induces the Ectopic Production of Root-Like Structures in RopGEF7ΔC-Overexpressing Seedlings.

(A) Relative expression levels of RopGEF7ΔC, as determined by qRT-PCR, in three transgenic lines compared with the wild type. Data presented are mean values of four biological repeats with sd.

(B) Seven-day-old wild-type seedling.

(C) and (D) Ectopic production of root-like structures from cotyledon tips in 10-d-old (C) and 7-d-old RPS5Apro:RopGEF7ΔC seedlings (D).

(E) and (F) Ectopic production of root-like structures near the shoot apex in 7-d-old RPS5Apro:RopGEF7ΔC seedlings.

(G) and (H) Expression of PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP in wild-type (G) and RopGEF7ΔC (H) embryos.

(I) and (J) Expression of PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP in wild-type (I) and RopGEF7ΔC embryos (J).

(K) Expression of PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP in root-like structures emerging from cotyledon tips in 7-d-old RopGEF7ΔC seedlings.

(L) Expression of PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP in root-like structures emerging from cotyledons and the main root of 7-d-old RopGEF7ΔC seedlings. Arrowheads point to root-like structures. Arrows indicate the expression of the marker genes in the root-like structures.

Bars = 0.5 mm in (B) to (F), 20 μm in (G) to (J), and 200 μm in (K) and (L).

Activation of RAC/ROP Signaling Induces Homeotic Transformations to Roots

To further study the function of RopGEF7, transgenic lines overexpressing full-length RopGEF7 and RopGEF7ΔC under the control of embryonic promoter RPS5A were generated. RopGEF7-overexpressing plants did not display obvious seedling phenotypes, while overexpression of RopGEF7ΔC resulted in ectopic production of white root-like tissues on the cotyledons and shoot apical region of seedlings. Among these, line L34 showed a relatively high level of transgene expression (Figure 5A) and produced seedlings with a striking phenotype, namely, having root-like structures emerging from the tips of cotyledons (cf. Figures 5C and 5D with 5B) at a frequency of ~3.8% (n = 184) in the T2 generation. The remaining population did not show obvious defects in root development, with their root length and lateral root number being only slightly different from those of the wild type (see Supplemental Figures 4E to 4G online). Similarly, seedlings derived from independent lines L27 and L26 also developed ectopic root-like structures but at the lower frequencies than those observed in L34 (1% of L27 seedlings [n = 202] and 1.99% of L26 seedlings [n = 251] examined) consistent with their lower RopGEF7ΔC expression level (Figure 5A). A similar phenotype was also seen in seedlings overexpressing a dominant-negative Rab5 GTPase, DN-Ara7, that affects endocytosis during embryogenesis (Dhonukshe et al., 2008). The homeotic transformation of leaves to roots in the DN-Ara7–expressing plants was shown to be due to the increased local auxin response and ectopic expression of PLT transcription factors in embryonic leaves (Dhonukshe et al., 2008). Some RopGEF7ΔC-overexpressing seedlings also developed root-like structures from the shoot apical meristem flanks (Figures 5E and 5F), which partially resembled the phenotypes seen in PLT2-overexpressing seedlings (Galinha et al., 2007). Growth of these root-like structures was arrested eventually, and these defective RopGEF7ΔC plants did not survive beyond the seedling stage.

To validate the identity of the root-like structures, we first analyzed the cell morphology under Normarski opitics. Some of the white structures contained rectangular cells without interspersed stomata, resembling root cells (see Supplemental Figure 4B online), which were distinct from the wild-type leaf epidermal pavement cells (see Supplemental Figure 4A online), while cells at the tip of some other root-like structures were similar to root columella cells (see Supplemental Figures 4C and 4D online), although they failed to accumulate starch granules.

To dissect the mechanism involved in ectopic RopGEF7ΔC-induced root formation, we examined the expression of two root-specific stem cell markers, PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP and PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP (Galinha et al., 2007), during embryogenesis. In wild-type embryos, YFP-labeled PLT1 and PLT2 fusion proteins were detected at the root pole (Figures 5G and 5I), and ectopic expression of PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP and PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP was observed in one or two cotyledon regions in RPS5A-RopGEF7ΔC embryos (Figures 5H and 5J) in addition to in the embryonic root. Furthermore, the root-like structures in RPS5A-RopGEF7ΔC seedlings also expressed YFP-labeled PLT1 and PLT2 (Figures 5K and 5L). These data indicate that ectopic expression of constitutively active RopGEF7 can induce the transformation of organ identity to roots during embryogenesis and therefore result in postembryonic root-like structures.

Altered Expression of PLT Genes in RopGEF7 RNAi Embryos and Plants

PLT expression is necessary for root stem cell maintenance, and the gradient distributions of PLT proteins are responsible for root formation (Aida et al., 2004; Galinha et al., 2007). PLT1 and PLT2 transcripts have been shown to have a maximum accumulation in the stem cell niche region of wild-type heart embryos and roots (Aida et al., 2004; Galinha et al., 2007). In situ hybridization showed that RopGEF7RNAi embryos (cf. Figures 6C and 6D with Figure 6B) and seedlings (cf. Figures 6G and 6H with Figure 6F) accumulated either substantially reduced or undetectable levels of PLT1 transcript. We also examined the YFP-tagged protein fusion level of PLT1 and PLT2 in the RopGEF7RNAi background. As shown in Figures 7B and 7J, PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP expression was absent or substantially reduced in the RopGEF7RNAi embryos and seedlings, while expression was observed in wild-type controls (Figures 7A and 7I). Similar to PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP expression, PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP expression was reduced in RopGEF7RNAi embryos (Figure 7D) and seedlings (Figure 7L), whereas its expression was normal in controls (Figures 7C and 7K). These results indicate that the maintenance of a root stem cell niche was affected by the downregulation of RopGEF7.

Figure 6.

Downregulation of RopGEF7 Suppresses PLT1 Transcript in in Situ Hybridization Assays.

(A) to (D) Whole-mount in situ hybridization with a sense probe for PLT1 in wild-type embryos (A) and an antisense probe in wild-type embryos (B) and two different RopGEF7RNAi embryos ([C] and [D]).

(E) to (H) In situ hybridization with a sense probe for PLT1 in the roots of 4-d-old of wild-type seedling (E) and an antisense probe in wild-type (F) and two different RopGEF7RNAi ([G] and [H]) roots.

Bars = 20 μm in (A) to (D) and 50 μm in (E) to (H).

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

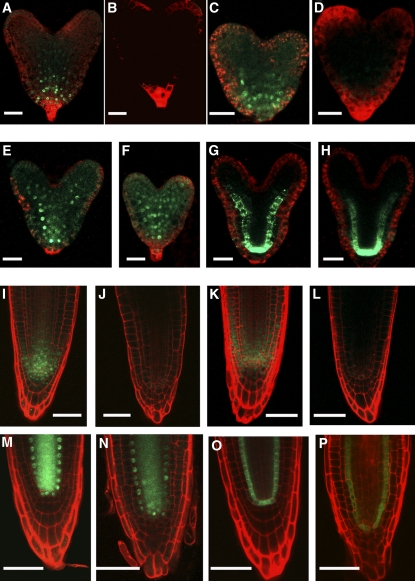

Figure 7.

RopGEF7 Mediates PLT1 and PLT2 Expression.

(A) and (B) Expression of PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP in wild-type (A) and RopGEF7RNAi (B) embryos.

(C) and (D) Expression of PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP in wild-type (C) and RopGEF7RNAi (D) embryos.

(E) and (F) SHRpro:SHR:GFP expression in wild-type (E) and RopGEF7RNAi (F) embryos.

(G) and (H) Expression of SCRpro:GFP in wild-type (G) and RopGEF7RNAi (H) embryos.

(I) and (J) Expression of PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP in the roots of 4-d-old wild-type (I) and RopGEF7RNAi (J) seedlings.

(K) and (L) Expression of PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP in the roots of 4-d-old wild-type (K) and RopGEF7RNAi (L) seedlings.

(M) and (N) SHRpro:SHR:GFP expression in the roots of 4-d-old wild-type (M) and RopGEF7RNAi (N) seedlings.

(O) and (P) SCRpro:GFP expression in the roots of 4-d-old wild-type (O) and RopGEF7RNAi (P) seedlings.

Bars 20 μm in (A) to (H) and 50 μm in (I) to (P).

SHR and SCR function in a pathway parallel to PLT1/PLT2, and the activity of these two pathways is essential for the specification and maintenance of the root stem cell niche (Helariutta et al., 2000; Sabatini et al., 2003; Aida et al., 2004). We examined the protein localization of SHRpro:SHR:GFP (green fluorescent protein) and the expression of SCRpro:GFP in RopGEF7RNAi embryos and seedlings. Unlike PLTs, the pattern for both SHR localization and SCR expression was not altered in RopGEF7RNAi embryos (Figures 7F and 7H) and seedlings (Figures 7N and 7P) relative to wild-type controls (Figures 7E, 7G, 7M, and 7O). These observations are consistent with RopGEF7 not being required for SHR/SCR action.

RopGEF7 Functions in the PLT Pathway

The phenotype of RopGEF7RNAi, together with PLT expression defects, suggested that RopGEF7 may participate in the PLT-mediated maintenance of QC identity and stem cells. This prompted us to investigate whether RopGEF7 interacts genetically with the PLT pathway. To detect interactions between RopGEF7RNAi and mutants affecting the auxin-dependent PLT pathway (plt1-4 plt2-2) (Aida et al., 2004), we obtained a mutant combination RopGEF7RNAi plt1-4 plt2-2. The root length (Figure 8A) and meristem size (cf. Figures 8C and 8G with Figures 8E and 8F) in RopGEF7RNAi plt1-4 plt2-2 were similar to those of plt1-4 plt2-2 double mutants (Figure 8F), suggesting that RopGEF7 acts in the PLT pathway.

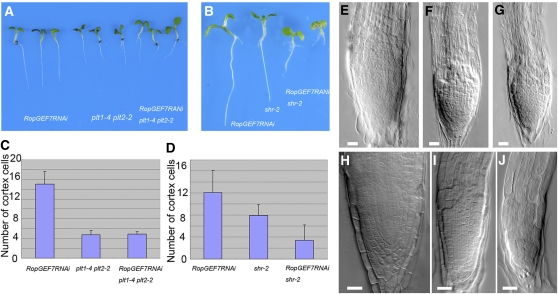

Figure 8.

Genetic Interaction between RopGEF7 and PLT or SHR Genes.

(A) Four-day-old seedling root phenotype of RopGEF7RNAi, plt1-4 plt2-2, and RopGEF7RNAi plt1-4 plt2-2.

(B) Six-day-old seedling root phenotype of RopGEF7RNAi, shr-2, and RopGEF7RNAi shr-2.

(C) Meristem size comparison of 4-d-old RopGEF7RNAi, plt1-4 plt2-2, and RopGEF7RNAi plt1-4 plt2-2 seedlings. Data presented are average and sd (n = 24 to 28).

(D) Meristem size comparison of 6-d-old RopGEF7RNAi, shr-2, and RopGEF7RNAi shr-2. Data presented are average and sd (n = 27 to 39).

(E) to (G) The root tips of 4-d-old RopGEF7RNAi (E), plt1-4 plt2-2 (F), and RopGEF7RNAi plt1-4 plt2-2 (G) seedlings.

(H) to (J) The root tips of 6-d-old RopGEF7RNAi (H), shr-2 (I), and RopGEF7RNAi shr-2 (J) seedlings.

Bars = 20 μm in (E) to (J).

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

To investigate whether PLTs have a role in defining RopGEF7 expression, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed. Results showed that the plt1-4 plt2-2 mutation did not affect the expression of RopGEF7 (see Supplemental Figure 5A online). We also crossed the RopGEF7pro:GUS line to the plt1-4 plt2-2 double mutant. GUS staining showed that RopGEF7pro:GUS reporter was normally expressed in plt1-4 plt2-2 mutants (see Supplemental Figures 5C and 5E compared with 5B and 5D online). Thus, PLT1 and PLT2 have little effect on restricting RopGEF7 expression to the root stem cell niche, suggesting that RopGEF7 may function upstream of PLTs in mediating the maintenance of the root stem cell niche.

To examine whether RopGEF7RNAi also acts in the SHR/SCR pathway, we obtained the mutant combination RopGEF7RNAi shr-2. Root phenotype analysis showed the effect of RopGEF7RNAi and shr-2 to be additive. The combined mutant had a shorter root and smaller meristem size than either the shr-2 single mutant or RopGEF7RNAi plants (cf. Figures 8B, 8D, and 8J with 8H and 8I), suggesting that RopGEF7 and SHR function in independent pathways.

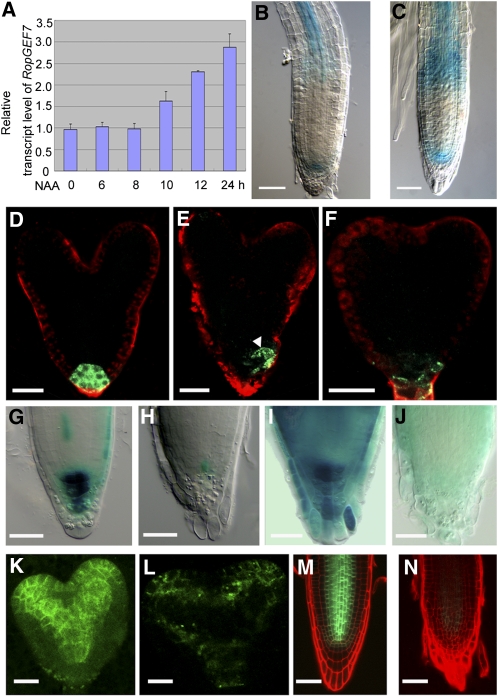

RopGEF7 Expression Is Regulated by Auxin

Simulation studies showed that auxin polar transport is sufficient to generate an auxin maximum at the root apex to specify the QC (Grieneisen et al., 2007). RopGEF7 is embryonically and postembryonically expressed in the QC, overlapping the expression pattern of auxin reporters, suggesting that it may act in an auxin-related pathway. To test this idea, we examined whether auxin regulated RopGEF7 expression using qRT-PCR analysis and RopGEF7pro:GUS transgenic plants. Seven-day-old wild-type seedlings treated with auxin (naphthalene acetic acid [NAA]) for different amounts of time were used to extract total RNA. qRT-PCR analysis showed that the relative RopGEF7 transcript level was elevated by 10 h after addition of NAA and reached the highest level by 24 h of treatment (Figure 9A). To further confirm the observation, we tested the RopGEF7pro:GUS transgenic lines for their responses to auxin. Similarly, RopGEF7 expression was induced by auxin treatment. Its expression domain became considerably broader, surrounding the QC and extending into the elongation zone of the primary root (Figure 9C) relative to untreated controls (Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

RopGEF7 Is Regulated by Auxin and Is Required for PIN1 Expression and Maintenance of Auxin Maximum.

(A) to (C) Induction of RopGEF7 expression in response to NAA treatment.

(A) The relative transcript level of RopGEF7, as determined by qRT-PCR analysis of 7-d-old wild-type seedlings treated without and with 10 μM NAA for different lengths of time as indicated. Data presented are mean values of three biological repeats with sd.

(B) and (C) GUS activity in the primary root of 5-d-old seedlings treated without (B) and with (C) 10 μM NAA for 12 h. GUS staining was for 12 h.

(D) to (F) GFP expression of DR5rev:GFP in wild-type embryo (D) and RopGEF7RNAi embryos ([E] and [F]). Arrowhead points to the shifted auxin maximum.

(G) and (H) In the absence of auxin treatment, DR5:GUS expression at root tips of 5-d-old wild-type (G) and RopGEF7RNAi (H) seedlings. GUS staining was for 12 h.

(I) and (J) Five-day-old seedlings were treated with 5 μM NAA for 12 h, and the activity of DR5:GUS was detected at root tips of wild-type (I) and RopGEF7RNAi (J) seedlings. GUS staining was for 6 h.

(K) and (L) PIN1pro:PIN1:GFP expression at heart stage in wild-type (K) and RopGEF7RNAi (L) embryos.

(M) and (N) PIN1pro:PIN1:GFP expression in 4-d-old seedling roots of wild-type (M) and RopGEF7RNAi (N).

Bars = 50 μm in (B), (C), (G) to (J), (M), and (N) and 20 μm in (D) to (F), (K), and (L).

RopGEF7 Is Required for PIN1 Expression and Maintenance of the Normal Auxin Response Maximum in the Root

To gain further insight into the potential function of RopGEF7 in auxin-related processes, we examined the expression of the well-characterized auxin reporters DR5rev:GFP and DR5:GUS (Ulmasov et al., 1997; Sabatini et al., 1999; Benková et al., 2003; Friml et al., 2003) in RopGEF7RNAi embryos and plants. The auxin response maximum was located in the QC, columella initial cells, and the future columella tier in control embryos (Figure 9D), but in the RNAi embryos, the reporter displayed an abnormal expression pattern with DR5 activity often displaced to one side (Figure 9E) or substantially reduced (Figure 9F). Furthermore, in comparison to wild-type roots (Figures 9G and 9I), GUS activity of DR5:GUS in an RNAi background was suppressed under endogenous auxin conditions and was not responsive to stimulation by auxin treatment (Figures 9H and 9J).

Since auxin efflux carrier PIN proteins are regulated by PLTs and contribute to embryonic development and RM patterning (Blilou et al., 2005; Galinha et al., 2007) and PLT1/PLT2 expression is suppressed in RopGEF7RNAi embryos and plants (Figures 6 and 7), we examined whether the expression of PIN1pro:PIN1:GFP was also affected in the RNAi embryos and seedling roots. In wild-type heart-stage embryos, PIN1-GFP protein was localized at the basal end of vascular cells within the central embryo axis and in cotyledons (Figure 9K), whereas in seedling roots, it was expressed in the stele, endodermis, and QC (Figure 9M). In RopGEF7RNAi embryos and roots, the accumulation of PIN1pro:PIN1:GFP in the equivalent regions and cell types was reduced (Figures 9L and 9N), indicating that RopGEF7 also regulates the expression of PIN1. These observations suggest that auxin polar transport and thus auxin distribution would be perturbed in RopGEF7RNAi embryos and roots because the reduced local accumulation of PIN1 and possibly of other PINs could potentially underlie the altered DR5 activity observed in RNAi embryos and plants. These results are consistent with the phenotypes observed in RopGEF7RNAi and suggest that the meristem defects observed in these RopGEF7 knockdown embryos and roots have resulted from abnormal auxin distribution and responses.

DISCUSSION

As RAC/ROP activators, RopGEFs are expected to play important roles in diverse signaling pathways. The results reported here, showing that RopGEF7 is an important regulator of stem cell niche maintenance, reveal the functional role of a member of this protein family in plant growth and development.

RopGEF7 Regulates the Maintenance of the Root Stem Cell Niche

RopGEF7 promoter GUS analysis showed that RopGEF7 expression is restricted to the QC precursor in developing embryos and to the QC in postembryonic roots (Figures 1A to 1E), consistent with a previous gene profiling study showing that RopGEF7 transcripts are enriched in the QC of seedling roots (Nawy et al., 2005). It also revealed temporal expression information for RopGEF7 during embryogenesis and showed that it could be detected as early as in the heart-stage embryos. These RopGEF7 expression properties together with defects in polar development of the basal root pattern and suppressed expression of QC-specific markers in RopGEF7 knockdown embryos indicate that RopGEF7 is crucial for QC maintenance during embryo development (Figures 2D to 2O). Furthermore, the inhibited root development and reduced RM zone in RopGEF7RNAi plants (Figure 3) also support that RopGEF7 is required for meristem maintenance during postembryonic development. The finding that embryo defects were observed prior to the heart stage in some RopGEF7 downregulated embryos (see Supplemental Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 2 online), albeit at considerably lower levels than in late embryonic stages, suggests that there may be a low level of RopGEF7 expression that is below the detection limit of the GUS staining assay but is required for early embryogenesis. Although a low level of off-target suppression of other RopGEFs could not be ruled out, it is unlikely because the RNAi construct was designed to target a relatively specific region of RopGEF7 and suppression of the closely related RopGEF1 was not observed (see Supplemental Figure 2B online). The relatively broad RopGEF7 expression in postembryonic plants (Figures 1E to 1G; see Supplemental Figure 1 online) suggests RopGEF7 may function in multiple signaling pathways throughout plant development. Maintenance of the QC and differentiation of the vasculature are both known to be dependent on auxin, and both locations are known to support the expression of many auxin-related genes (Birnbaum et al., 2003; Nawy et al., 2005). This and the observation that RopGEF7 expression is enhanced by exogenous auxin treatment would support the notion that under normal growth and developmental conditions, RopGEF7 expression is also dependent on and/or functionally related to auxin regulation, thus integrating it into a broader auxin-related regulatory scheme.

RopGEF7 Interacts with PLT to Mediate RM Patterning

Dependence of PLT expression on RopGEF7 (Figures 6 and 7) and the comparable phenotypes shared by the combined RopGEF7RNAi plt1-4 plt2-2 mutant and plt1-4 plt2-2 (Figure 8) suggest that RopGEF7 and PLT1/PLT2 function in a common pathway. How RopGEF7-activated RAC/ROP signaling (Figure 4) intersect with the regulation of PLT expression and function in RM pattern determination remains to be determined. However, the observation that overexpression of the constitutively active RopGEF7ΔC (Figure 5) induces a phenotype similar to that of PLT1 or PLT2 overexpression (Aida et al., 2004; Galinha et al., 2007) or of plants expressing DN-Ara7 (Dhonukshe et al., 2008), namely, the development of ectopic root-like structures on the cotyledon and shoot apex, may provide some hints. Previous studies have attributed these homeotic transformations to ectopic PLT activity during embryogenesis in an auxin-dependent or -independent manner (Aida et al., 2004; Dhonukshe et al., 2008). The expression of DN-Ara7 should inhibit endocytosis and therefore would have a similar effect of an increase in intracellular auxin, which inhibits clathrin-dependent endocytosis, including that of PINs (Robert et al., 2010), and thereby affects local auxin concentration. Increasing RAC/ROP signaling by overexpressing CA-At RAC10 also inhibits endocytosis (Bloch et al., 2005). Taken together, augmenting RAC/ROP signaling by overexpressing RopGEF7ΔC should therefore also result in the inhibition of PIN endocytosis. Since PLT expression is dependent on auxin, the altered auxin condition in normally non-root meristematic regions could stimulate PLT expression, resulting in ectopic root development. These considerations suggest that RopGEF7 and PLT could interact via the effect of RAC/ROP signaling on PIN localization (Hazak et al., 2010), and thus on local auxin concentration, to affect PLT expression and mediate RM patterning.

On the other hand, the stem cell niche domain in ectopic roots induced by PLT overexpression did not overlap with a high level of auxin, as reflected by the auxin reporter IAA2:GUS, suggesting that expression of the PLT genes alone is necessary and sufficient for specification of the root stem cell niche (Aida et al., 2004). Therefore, since RopGEF7 regulates PLT expression, the ectopic root production observed in RopGEF7ΔC-overexpressing seedlings could be a direct consequence of RopGEF7-stimulated PLT activity, resulting in ectopic conversion to embryonic root apical characteristics. Furthermore, since PLT expression is dependent on auxin and on RopGEF7, the observation that auxin also stimulates RopGEF7 expression suggests a feed-forward mechanism may also be involved, whereby the delayed auxin-stimulated RopGEF7 levels play an important role in sustaining PLT expression. The precise molecular mechanism underlying RopGEF7 function in root stem cell maintenance remains to be elucidated; our results nonetheless support the notion that RopGEF7 modulates this process by regulating the PLT pathway.

RopGEF7 as Part of a Network That Regulates Auxin Signaling

Given that auxin activates RAC/ROPs (Tao et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2010), the observations that RopGEF7 expression (e.g., in the QC) (Figure 1) overlaps with regions of auxin maxima and is stimulated by auxin treatment suggest that RopGEF7 is likely part of a regulatory loop that mediates an appropriate level of auxin signaling for root stem cell niche maintenance throughout plant growth and development. However, it should be noted that auxin-stimulated RopGEF7 transcription was detected only hours after auxin treatment, which is considerably slower than RAC/ROP activation by auxin (Tao et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2010) and auxin-regulated early response gene expression (Abel et al., 1995). Thus, while RopGEF7 may contribute to mediating auxin-activated RAC/ROP signaling, the auxin-regulated RopGEF7 expression is apparently mediated by pathways different from those that regulate early auxin-responsive gene expression (Abel et al., 1995). Furthermore, upstream regulators of RopGEF7 signaling activity remain unknown, although receptor-like kinases, such as the pollen receptor kinases from tomato and Arabidopsis (Kaothien et al., 2005; Zhang and McCormick, 2007; Zhang et al., 2008) and, more recently, the FERONIA receptor-like kinase from Arabidopsis, have been shown to regulate RAC/ROP signaling. In particular, FERONIA has been shown to interact directly with RopGEFs, including RopGEF7 (Duan et al., 2010). Given the findings that FERONIA regulates reactive oxygen species production in roots and root hairs (Duan et al., 2010) and reactive oxygen species apparently play an important role in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation during root development (Tsukagoshi et al., 2010), it is plausible that FERONIA and/or its related receptor-like kinases whose expression pattern overlaps with that of RopGEF7 could act as upstream regulators of RopGEF7.

Auxin is essential for embryo patterning and RM function. The aberrant expression patterns of the auxin-responsive reporters DR5rev:GFP and DR5:GUS and the dramatic reduction in PIN1 expression in RopGEF7 RNAi embryos and seedlings (Figures 9D to 9N) suggest that these defects could be mediated by defective auxin distribution and the resulting auxin-regulated responses. The observations that RopGEFs activate RAC/ROPs and mediate RAC/ROP-induced cell polarization (Kaothien et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008) and that RopGEF7 interacts with At RAC1 and activates At RACs (Figure 4) suggest that RopGEF7 may activate At RACs, including At RAC1, to regulate auxin-induced expression of PLT genes. Since auxin activates RAC/ROPs, which in turn stimulate auxin-responsive gene expression via regulated proteolysis of repressor AUX/IAA proteins (Tao et al., 2002, 2005), and inhibits endocytosis (Bloch et al., 2005), and the RAC/ROP effector ICR1 mediates PIN polarization (Hazak et al., 2010), RopGEF7 could regulate PIN accumulation and polarization directly through RAC/ROP signaling. It is noteworthy that altered PIN polarity could lead to an altered local auxin gradient, which in turn would affect auxin-mediated PLT expression (Blilou et al., 2005; Dinneny and Benfey, 2008). Alternatively, the fact that RopGEF7 is required for PLT expression, which is known to be important for the expression of PINs (Blilou et al., 2005), suggests that the reduced accumulation of PIN1-GFP in RopGEF7 RNAi embryos and seedling roots (Figures 9K to 9N) could be caused by the decreased level of PLT1/PLT2 expression. Therefore, RopGEF7 could affect PIN accumulation and polarization in various ways and impact polar auxin transport and thereby function as part of a homeostatic regulatory loop that mediates auxin signaling pathways throughout development. Identifying upstream regulators and downstream target processes of RopGEF7 will help elucidate how this apparently interconnected and relatively complex regulatory network involving auxin, RAC/ROPs, and PLTs works in regulating the root stem cell niche.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia and Wassilewskija were used. Some of the marker lines and mutants used were previously described: QC25:GUS and QC46:GUS (Sabatini et al., 2003); PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP and PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP (Galinha et al., 2007); SHRpro:SHR:GFP (Nakajima et al., 2001); SCR pro:GFP (Wysocka-Diller et al.,2000); Cyclin B1;1:GUS (Colón-Carmona at al., 1999); PIN1pro:PIN1:GFP (Benková et al., 2003); DR5rev:GFP (Benková et al., 2003); DR5:GUS (Ulmasov et al., 1999); plt1-4 plt2-2 (Aida et al., 2004); and shr-2 (Fukaki et al., 1998).

Seeds were surface sterilized and germinated on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) agar medium supplemented with 1.5% Suc at 22°C with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle in a phytotron set. Seedlings were transferred to soil 7 to 10 d after germination and grown under the same conditions.

Chimeric Gene Construction and Plant Transformation

RopGEF7pro:GUS was generated by inserting a 2.826-kb RopGEF7 promoter sequence into pBI101.1 at the HindIII and XbaI sites. A 490-bp cDNA fragment of RopGEF7 between 1296 to 1783 bp that corresponds to the 3′ region of the coding sequence and spans the most diverged region among all RopGEFs was used for the construction of RopGEF7RNAi. The RNAi construct was inserted into the HindIII and SalI sites (for forward insert) and the MluI and PstI sites (for the reverse insert) of the pRNAi-35S vector (Hu and Liu, 2006). To create the embryonic promoter RPS5A (Weijers et al., 2001), which drives RopGEF7 RNAi, the 35S promoter fragment of the pRNAi-35S vector was replaced by a 2.24-kb Arabidopsis RPS5A promoter. To generate the constructs for overexpression of wild-type RopGEF7 and the C-terminal-truncated version (RopGEF7ΔC), the coding sequence of RopGEF7 and its truncated fragment were inserted into the pAC1352 binary vector behind the 35SCAMV promoter (Rodermel et al., 1988) and downstream of the RPS5A promoter in modified pCAMBIA1300, respectively.

The above constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and used to transform Arabidopsis by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998).The sequences of the primers used in the chimeric gene construction are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR Analysis

For analysis of RopGEF7 gene expression, total RNA was extracted from 7- to 10-d-old seedlings or embryos using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA contamination was removed by RNA-free DNase I treatment. Two micrograms of RNA was reverse transcribed with oligo(dT) primers in a total volume of 20 μL according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PrimeScript cDNA synthesis kit; TakaRa). One microliter of first-strand cDNAs was used as templates for PCR amplification using RopGEF7-specific primers with 28 to 32 cycles. Expression levels of RopGEF7 were normalized to Actin 2 expression levels. qRT-PCR analysis was performed in a total volume of 25 μL with 2 μL of cDNA template, 0.5 μL 10 μM gene-specific primers, and 12.5 μL SYBR Premix (Takara) on a DNA Engine Option 2 real-time PCR machine (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expression levels of RopGEF7 in transgenic plants and embryos were normalized to those of Actin 7 and then compared with those of the wild type. Data presented are the averages from at least three biological replicates with sd.

The sequences of the gene-specific primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online.

Auxin Treatment

Wild-type (Columbia) seeds were surface sterilized and germinated on half-strength MS agar medium. Seven- to ten-day-old seedlings were transferred to double distilled water in the presence or absence of 10 μM NAA. Total RNA was extracted after 0, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h of treatment, and expression levels of RopGEF7 were analyzed by qRT-PCR.

Root Length and Meristem Size Analysis

Seeds were germinated on half-strength MS medium (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1.5% Suc and 0.8% agar and grown in a vertical position from 3 to 12 d. The primary root length was measured. Results presented are averages of 30 to 50 seedlings. Root growth experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. Meristem size was determined as the number of cells in the cortex files in the meristem before the elongation zone.

Marker Gene Analysis and Genetic Interaction Assays

QC markers PLT1pro:PLT1:YFP, PLT2pro:PLT2:YFP, SHRpro:SHR:GFP, SCRpro:GFP, CYCB1;1:GUS, PIN1pro:PIN1:GFP, DR5rev:GFP, and DR5:GUS were crossed to the phenotypically strongest transgenic line of RopGEF7RNAi. Homozygous plants for both RopGEF7RNAi and marker genes were obtained in the F2 population. For genetic interaction analysis, shr-2 and plt1-4 plt2-2 mutants were crossed to RopGEF7RNAi plants. Homozygotes for shr-2, plt1-4 plt2-2, and RopGEF7RNAi were isolated in the F2 or F3 generation. Analysis of these homozygotes was conducted in the next generation while parental plants were used as a control.

In Situ Hybridization

RNA in situ hybridization of whole-mount embryos and 3-d-old seedlings was performed as described by Hejátko et al. (2006). A 282-bp fragment from nucleotides 209 to 491 of the PLT1 coding sequence was used to generate a probe as described with modification (Aida et al., 2004). The PCR fragment was inserted into the XbaI to HindIII sites of the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and transcribed in vitro from the T7 promoter or SP6 for sense or antisense strand synthesis using the Digoxigenin RNA labeling kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche).

Microscopy

Ovules and seedling roots were cleared in a modified Hoyer’s solution and an HCG solution as described by Liu and Meinke (1998) and Sabatini et al. (1999), respectively. Samples were viewed using Nomarski optics on an Olympus BX51 microscope connected to a Ritiga 2000R digital camera. Histochemical assays of GUS activities were performed as described by Weijers et al. (2001). Embryos, tissues, and seedlings were incubated in GUS staining buffer [0.1 M phosphate, pH 7.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 1 mM K4Fe(CN)6·3H2O, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1 mM X-gluc] from 3 h to overnight at 37°C. Starch staining of seedlings or the GUS-stained seedling was performed by dipping root tips in a 1:1 dilution of Lugol’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and then rinsing them with distilled water and mounting them in chloral hydrate–containing clearing solution for visualization.

For confocal microscopy, dissected embryos and seedling roots were stained with 1 μg/mL FM4-64 (Molecular Probes) and 100 μg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively, and mounted in 5% glycerol. Confocal images were taken using a Zeiss LSM510 META laser scanning microscope with the following excitation (Ex) and emission (Em) wavelengths (Ex/Em): 488 nm/505 to 530 nm for GFP; 514 nm/530 to 600 nm for YFP; 543 nm/600 nm for FM4-64; and 561 nm/591 to 635 nm for propidium iodide. Approximately 20 to 30 individual samples were examined under the Olympus BX51 microscope prior to confocal microscopy. Five to six samples were used for acquiring confocal images. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with comparable results. Seedlings of RopGEF7ΔC-overexpressing lines were photographed using the Nikon SMZ1000 microscope and Nikon Digital sight DS-Fi1 camera.

Analysis of Active At RACs in RopGEF7ΔC-Overexpressing Plants

To demonstrate the RopGEF7ΔC activation of At RACs, we used RopGEF7ΔC-overexpressing plants and the p21 PBD fused with glutathione S-transferase (GST) for pull-down assays, as described previously (Tao et al., 2002). PBD-GST was used as bait for GTP-bound At RACs. Bound proteins were eluted and examined by immunoblot analysis after SDS-PAGE. To ensure comparable levels of proteins were loaded for immunoblot analysis, 10 μL from 500 μL of total protein extracts was analyzed first for protein amount approximation. At RAC proteins were detected with a polyclonal antibody against Nt Rac1 (Tao et al., 2002) and the chemiluminescence detection kit (Thermo-Scientific).

Subcellular Localization and BiFC Analysis in Arabidopsis Protoplasts

Plasmids for 35Spro:YFP:RopGEF7, 35Spro:YFP:RopGEF7ΔC, and 35Spro:YFP:At RAC1 were generated by inserting a RopGEF7 coding sequence, a truncated fragment of RopGEF7, and At RAC1 RCR fragments, respectively, into the EcoRI and SalI sites of a modified Bluescript pSK vector containing 35Spro:YFP (Tao et al., 2005). The resulting constructs were transformed into Arabidopsis protoplasts for subcellular localization analysis. To construct the fusion proteins of cYFP-RopGEF7, cYFP-RopGEF7ΔC, and nYFP-At RAC1, RopGEF7, RopGEF7ΔC, and At RAC1 coding sequences were inserted into the EcoRI and SalI sites of pSAT6-nEYFP-C1 and pSAT6-cEYFP-C1 vectors (Citovsky et al., 2006), respectively. Both plasmids of 35Spro:cYFP:RopGEF7 or 35Spro:cYFP:RopGEF7ΔC and 35Spro:nYF: At RAC1 were cotransformed into Arabidopsis protoplasts for BiFC assays.

Protoplast isolation and transfection were performed as described previously (Tao et al., 2005). YFP was visualized by an Olympus BX51 microscope using YFP filter sets: the excitation and emission filters Ex490 to 510 nm/DM515 nm/BA 520 to 550 nm (Tao et al., 2005). The sequences of the primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: ACTIN7 (At5g09810), CYCB1;1 (At4g37490), PIN1 (At1g73590), PLT1 (At3g20840), PLT2 (At1g51190), At RAC1 (At2g17800), RopGEF1 (At4g38430), RopGEF7 (At5g02010), SCR (At3g54220), and SHR (At4g37650).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. RopGEF7 Expression Pattern Analysis.

Supplemental Figure 2. Early Embryo Phenotypes Are Observed in the RPS5Apro:RopGEF7RNAi Lines.

Supplemental Figure 3. Analysis of 35Spro:RopGEF7 RNAi Transgenic Lines.

Supplemental Figure 4. Analysis of RPS5Apro:RopGEF7ΔC-Overexpressing Transgenic Plants.

Supplemental Figure 5. Expression of RopGEF7 in plt1-4 plt2-2 Double Mutant.

Supplemental Table 1. Primers Used in This Study.

Supplemental Table 2. Frequencies of Embryo Defects in RPS5Apro:RopGEF7RNAi Plants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the ABRC (Ohio State University) and Ben Scheres, Philip Benfey, Chunming Liu, Jian Xu, and Dong Liu for providing seeds used in this study. We thank Yaoguang Liu and Hongquan Yang for providing RNAi and BiFC vectors. We thank Hen-ming Wu for comments on the manuscript and Jianmin Li, Jian Xu, Chunming Liu, and Zhenghui He for helpful discussion on this work. This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2007CB948200) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (90817005 and 30770215).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.C., H.L., J.K., and L.T. designed the experiments. M.C., H.L., J.K., Y.Y., N.Z., R.L., J.Y., and J.H. performed the experiments. M.C., L.T., and C.L. analyzed the data. L.T. and A.Y.C. wrote the article.

References

- Abel S., Nguyen M.D., Theologis A. (1995). The PS-IAA4/5-like family of early auxin-inducible mRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Mol. Biol. 251: 533–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aida M., Beis D., Heidstra R., Willemsen V., Blilou I., Galinha C., Nussaume L., Noh Y.S., Amasino R., Scheres B. (2004). The PLETHORA genes mediate patterning of the Arabidopsis root stem cell niche. Cell 119: 109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benková E., Michniewicz M., Sauer M., Teichmann T., Seifertová D., Jürgens G., Friml J. (2003). Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell 115: 591–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berken A., Thomas C., Wittinghofer A. (2005). A new family of RhoGEFs activates the Rop molecular switch in plants. Nature 436: 1176–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum K., Shasha D.E., Wang J.Y., Jung J.W., Lambert G.M., Galbraith D.W., Benfey P.N. (2003). A gene expression map of the Arabidopsis root. Science 302: 1956–1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff F., Vahlkamp L., Molendijk A., Palme K. (2000). Localization of AtROP4 and AtROP6 and interaction with the guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor AtRhoGDI1 from Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 42: 515–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blilou I., Xu J., Wildwater M., Willemsen V., Paponov I., Friml J., Heidstra R., Aida M., Palme K., Scheres B. (2005). The PIN auxin efflux facilitator network controls growth and patterning in Arabidopsis roots. Nature 433: 39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch D., Lavy M., Efrat Y., Efroni I., Bracha-Drori K., Abu-Abied M., Sadot E., Yalovsky S. (2005). Ectopic expression of an activated RAC in Arabidopsis disrupts membrane cycling. Mol. Biol. Cell 16: 1913–1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A.Y., Duan Q.H., Costa S.S., de Graaf B.H., Di Stilio V.S., Feijo J., Wu H.M. (2008). The dynamic pollen tube cytoskeleton: Live cell studies using actin-binding and microtubule-binding reporter proteins. Mol. Plant 1: 686–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky V., Lee L.Y., Vyas S., Glick E., Chen M.H., Vainstein A., Gafni Y., Gelvin S.B., Tzfira T. (2006). Subcellular localization of interacting proteins by bimolecular fluorescence complementation in planta. J. Mol. Biol. 362: 1120–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colón-Carmona A., You R., Haimovitch-Gal T., Doerner P. (1999). Technical advance: Spatio-temporal analysis of mitotic activity with a labile cyclin-GUS fusion protein. Plant J. 20: 503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P., et al. (2008). Generation of cell polarity in plants links endocytosis, auxin distribution and cell fate decisions. Nature 456: 962–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Dinneny J.R., Benfey P.N. (2008). Plant stem cell niches: Standing the test of time. Cell 132: 553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q., Kita D., Li C., Cheung A.Y., Wu H.M. (2010). FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 17821–17826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J., Benková E., Blilou I., Wisniewska J., Hamann T., Ljung K., Woody S., Sandberg G., Scheres B., Jürgens G., Palme K. (2002). AtPIN4 mediates sink-driven auxin gradients and root patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell 108: 661–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J., Vieten A., Sauer M., Weijers D., Schwarz H., Hamann T., Offringa R., Jürgens G. (2003). Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature 426: 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J. E. (2010). Evolution of the ROP GTPase signaling module. In Integrated G Proteins Signaling in Plants, Yalovsky S., Baluska F., Jones A., (New York: Springer; ), pp. 305–327 [Google Scholar]

- Fukaki H., Wysocka-Diller J., Kato T., Fujisawa H., Benfey P.N., Tasaka M. (1998). Genetic evidence that the endodermis is essential for shoot gravitropism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 14: 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinha C., Hofhuis H., Luijten M., Willemsen V., Blilou I., Heidstra R., Scheres B. (2007). PLETHORA proteins as dose-dependent master regulators of Arabidopsis root development. Nature 449: 1053–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieneisen V.A., Xu J., Marée A.F., Hogeweg P., Scheres B. (2007). Auxin transport is sufficient to generate a maximum and gradient guiding root growth. Nature 449: 1008–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y., Li S., Lord E.M., Yang Z. (2006). Members of a novel class of Arabidopsis Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors control Rho GTPase-dependent polar growth. Plant Cell 18: 366–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazak O., Bloch D., Poraty L., Sternberg H., Zhang J., Friml J., Yalovsky S. (2010). A rho scaffold integrates the secretory system with feedback mechanisms in regulation of auxin distribution. PLoS Biol. 8: e1000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejátko J., Blilou I., Brewer P.B., Friml J., Scheres B., Benková E. (2006). In situ hybridization technique for mRNA detection in whole mount Arabidopsis samples. Nat. Protoc. 1: 1939–1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helariutta Y., Fukaki H., Wysocka-Diller J., Nakajima K., Jung J., Sena G., Hauser M.T., Benfey P.N. (2000). The SHORT-ROOT gene controls radial patterning of the Arabidopsis root through radial signaling. Cell 101: 555–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Liu Y. (2006). The construction of RNAi vectors and the use for gene silencing in rice. Mol. Plant Breed. 4: 621–626 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K., Feldman L.J. (2005). Regulation of root apical meristem development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21: 485–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaothien P., Ok S.H., Shuai B., Wengier D., Cotter R., Kelley D., Kiriakopolos S., Muschietti J., McCormick S. (2005). Kinase partner protein interacts with the LePRK1 and LePRK2 receptor kinases and plays a role in polarized pollen tube growth. Plant J. 42: 492–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler S.A., Shimosato-Asano H., Keinath N.F., Wuest S.E., Ingram G., Panstruga R., Grossniklaus U. (2010). Conserved molecular components for pollen tube reception and fungal invasion. Science 330: 968–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahre U., Becker C., Schmitt A.C., Kost B. (2006). Nt-RhoGDI2 regulates Rac/Rop signaling and polar cell growth in tobacco pollen tubes. Plant J. 46: 1018–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori R., Amano Y., Ogawa-Ohnishi M., Matsubayashi Y. (2009). Identification of tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 15067–15072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornet N., Scheres B. (2009). Members of the GCN5 histone acetyltransferase complex regulate PLETHORA-mediated root stem cell niche maintenance and transit amplifying cell proliferation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 1070–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavy M., Bloch D., Hazak O., Gutman I., Poraty L., Sorek N., Sternberg H., Yalovsky S. (2007). A novel ROP/RAC effector links cell polarity, root-meristem maintenance, and vesicle trafficking. Curr. Biol. 17: 947–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J.A., Ohno C., Smith Z.R., Meyerowitz E.M. (2006). TOPLESS regulates apical embryonic fate in Arabidopsis. Science 312: 1520–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.M., Meinke D.W. (1998). The titan mutants of Arabidopsis are disrupted in mitosis and cell cycle control during seed development. Plant J. 16: 21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y., Ogawa-Ohnishi M., Mori A., Matsubayashi Y. (2010). Secreted peptide signals required for maintenance of root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Science 329: 1065–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K., Sena G., Nawy T., Benfey P.N. (2001). Intercellular movement of the putative transcription factor SHR in root patterning. Nature 413: 307–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawy T., Lee J.Y., Colinas J., Wang J.Y., Thongrod S.C., Malamy J.E., Birnbaum K., Benfey P.N. (2005). Transcriptional profile of the Arabidopsis root quiescent center. Plant Cell 17: 1908–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibau C., Cheung A. (2011). New insights into the functional roles of CrRLKs in the control of plant cell growth and development. Plant Signal. Behav. 6: 655–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibau C., Wu H.M., Cheung A.Y. (2006). RAC/ROP GTPases: ‘Hubs’ for signal integration and diversification in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 11: 309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert S., et al. (2010). ABP1 mediates auxin inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocytosis in Arabidopsis. Cell 143: 111–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodermel S.R., Abbott M.S., Bogorad L. (1988). Nuclear-organelle interactions: nuclear antisense gene inhibits ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase enzyme levels in transformed tobacco plants. Cell 55: 673–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini S., Beis D., Wolkenfelt H., Murfett J., Guilfoyle T., Malamy J., Benfey P., Leyser O., Bechtold N., Weisbeek P., Scheres B. (1999). An auxin-dependent distal organizer of pattern and polarity in the Arabidopsis root. Cell 99: 463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini S., Heidstra R., Wildwater M., Scheres B. (2003). SCARECROW is involved in positioning the stem cell niche in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Genes Dev. 17: 354–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B. (2007). Stem-cell niches: Nursery rhymes across kingdoms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8: 345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Z.R., Long J.A. (2010). Control of Arabidopsis apical-basal embryo polarity by antagonistic transcription factors. Nature 464: 423–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szemenyei H., Hannon M., Long J.A. (2008). TOPLESS mediates auxin-dependent transcriptional repression during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Science 319: 1384–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao L.Z., Cheung A.Y., Nibau C., Wu H.M. (2005). RAC GTPases in tobacco and Arabidopsis mediate auxin-induced formation of proteolytically active nuclear protein bodies that contain AUX/IAA proteins. Plant Cell 17: 2369–2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao L.Z., Cheung A.Y., Wu H.M. (2002). Plant Rac-like GTPases are activated by auxin and mediate auxin-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell 14: 2745–2760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C., Fricke I., Scrima A., Berken A., Wittinghofer A. (2007). Structural evidence for a common intermediate in small G protein-GEF reactions. Mol. Cell 25: 141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotochaud A.E., Hao T., Wu G., Yang Z., Clark S.E. (1999). The CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase requires CLAVATA3 for its assembly into a signaling complex that includes KAPP and a Rho-related protein. Plant Cell 11: 393–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukagoshi H., Busch W., Benfey P.N. (2010). Transcriptional regulation of ROS controls transition from proliferation to differentiation in the root. Cell 143: 606–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T., Hagen G., Guilfoyle T.J. (1999). Activation and repression of transcription by auxin-response factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 5844–5849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T., Murfett J., Hagen G., Guilfoyle T.J. (1997). Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell 9: 1963–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg C., Willemsen V., Hendriks G., Weisbeek P., Scheres B. (1997). Short-range control of cell differentiation in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Nature 390: 287–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D., Jürgens G. (2002). Stem cells that make stems. Nature 415: 751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijers D., Franke-van Dijk M., Vencken R.J., Quint A., Hooykaas P., Offringa R. (2001). An Arabidopsis Minute-like phenotype caused by a semi-dominant mutation in a RIBOSOMAL PROTEIN S5 gene. Development 128: 4289–4299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Li H., Yang Z. (2000). Arabidopsis RopGAPs are a novel family of rho GTPase-activating proteins that require the Cdc42/Rac-interactive binding motif for rop-specific GTPase stimulation. Plant Physiol. 124: 1625–1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.M., Hazak O., Cheung A.Y., Yalovsky S. (2011). RAC/ROP GTPases and auxin signaling. Plant Cell 23: 1208–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka-Diller J.W., Helariutta Y., Fukaki H., Malamy J.E., Benfey P.N. (2000). Molecular analysis of SCARECROW function reveals a radial patterning mechanism common to root and shoot. Development 127: 595–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T., Wen M., Nagawa S., Fu Y., Chen J.G., Wu M.J., Perrot-Rechenmann C., Friml J., Jones A.M., Yang Z. (2010). Cell surface- and rho GTPase-based auxin signaling controls cellular interdigitation in Arabidopsis. Cell 143: 99–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalovsky S., Bloch D., Sorek N., Kost B. (2008). Regulation of membrane trafficking, cytoskeleton dynamics, and cell polarity by ROP/RAC GTPases. Plant Physiol. 147: 1527–1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. (2008). Cell polarity signaling in Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 24: 551–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Fu Y. (2007). ROP/RAC GTPase signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10: 490–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Wengier D., Shuai B., Gui C.P., Muschietti J., McCormick S., Tang W.H. (2008). The pollen receptor kinase LePRK2 mediates growth-promoting signals and positively regulates pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Physiol. 148: 1368–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., McCormick S. (2007). A distinct mechanism regulating a pollen-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the small GTPase Rop in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 18830–18835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Wei L., Xu J., Zhai Q., Jiang H., Chen R., Chen Q., Sun J., Chu J., Zhu L., Liu C.M., Li C. (2010). Arabidopsis Tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase acts in the auxin/PLETHORA pathway in regulating postembryonic maintenance of the root stem cell niche. Plant Cell 22: 3692–3709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.