Abstract

Coordinated regulation of the adult neurogenic subventricular zone (SVZ) is accomplished by a myriad of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The neurotransmitter dopamine is one regulatory molecule implicated in SVZ function. Nigrostriatal and ventral tegmental area (VTA) midbrain dopamine neurons innervate regions adjacent to the SVZ, and dopamine synapses are found on SVZ cells. Cell division within the SVZ is decreased in humans with Parkinson's disease and in animal models of Parkinson's disease following exposure to toxins that selectively remove nigrostriatal neurons, suggesting that dopamine is critical for SVZ function and nigrostriatal neurons are the main suppliers of SVZ dopamine. However, when we examined the aphakia mouse, which is deficient in nigrostriatal neurons, we found no detrimental effect to SVZ proliferation or organization. Instead, dopamine innervation of the SVZ tracked to neurons at the ventrolateral boundary of the VTA. This same dopaminergic neuron population also innervated the SVZ of control mice. Characterization of these neurons revealed expression of proteins indicative of VTA neurons. Furthermore, exposure to the neurotoxin MPTP depleted neurons in the ventrolateral VTA and resulted in decreased SVZ proliferation. Together, these results reveal that dopamine signaling in the SVZ originates from a population of midbrain neurons more typically associated with motivational and reward processing.

Introduction

Neurogenesis in the adult brain occurs primarily in two stem cell niches, the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and the subventricular zone (SVZ) along the lateral wall of the lateral ventricle (Altman and Das, 1966; Hinds, 1968; Cameron and Gould, 1994; Eriksson et al., 1998; Gould et al., 1999). Here we focus on the SVZ, which throughout adulthood generates immature neurons that migrate to the olfactory bulb, integrate into the existing neuronal network, and function in odor perception discrimination (Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1993; Doetsch et al., 1999; Bédard and Parent, 2004; Curtis et al., 2007). Several molecules released by cells within, and adjacent to, the SVZ have regulatory roles in SVZ neurogenesis, including growth factors such as FGF, EGF, and VEGF, and several neurotransmitters, notably GABA, glutamate, and 5-HT (for review, see Lennington et al., 2003; Pathania et al., 2010; Conover and Shook, 2011). Another neurotransmitter, dopamine, has been reported to stimulate proliferation within the SVZ (Höglinger et al., 2004), but the origin and role of dopamine afferents in the SVZ are still unclear.

A9 nigrostriatal dopamine neurons originating from the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) innervate the striatum, which borders the dorsolateral SVZ. These neurons mediate sensorimotor function (DeLong et al., 1983). The ventral SVZ is bordered by the nucleus accumbens, which is innervated by A10 dopamine neurons originating from the ventral tegmental area (VTA). These neurons mediate affect, reward, and motivational learning (Montague et al., 1996; Hollerman and Schultz, 1998). Injection of neuronal tracers into the midbrain of nonhuman primates revealed organized, topographical projections of midbrain dopamine neurons to the SVZ (Freundlieb et al., 2006). Additionally, it has been shown that SVZ cells possess dopamine receptors and dopaminergic synapses (Höglinger et al., 2004). Based on studies showing declines in SVZ proliferation in Parkinson's disease patients and following A9-selective lesioning in rodents, the origin of midbrain inputs to the SVZ was thought to be SNpc neurons (Baker et al., 2004; Höglinger et al., 2004). However, others have proposed that A10 VTA afferents, in addition to innervating the neighboring nucleus accumbens, extend into the ventromedial striatum immediately adjacent to the SVZ (Björklund and Dunnett, 2007). Innervation by the VTA would implicate the motivational reward system in olfactory neurogenesis, versus the sensorimotor system as currently reported. To date, the molecular signature and projection targets of midbrain dopaminergic neuron populations and their contribution to SVZ neurogenesis have not been fully investigated.

To examine the origin and role of dopamine signaling in the SVZ, we evaluated the aphakia (ak) mouse, a genetic model for dopaminergic neuron loss and an alternative to standard chemical methods that produce acute lesions of dopaminergic neurons. During ak development, midbrain dopamine neurons are born, but up to 90% of SNpc neurons are lost by birth, resulting in severe depletion of dopaminergic innervation of the striatum. VTA dopaminergic neuron projections to the nucleus accumbens are only modestly affected (Hwang et al., 2003; Nunes et al., 2003; van den Munckhof et al., 2003). Since ak mice have normal lifespans, we could examine whether loss of SNpc neuron-generated dopamine affected SVZ organization and function. Here, we report that a subpopulation of dopaminergic neurons with characteristics more typically associated with VTA neurons is the primary supplier of dopamine to the SVZ in ak as well as control mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Male ak mice were provided by Drs. Kwang-Soo Kim and Dong-Youn Hwang (McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Belmont, MA). Male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Animal procedures were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Connecticut and conformed to National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Immunohistochemistry.

Mice were perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline followed by 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were fixed overnight in 3% paraformaldehyde at 4°C and then washed in PBS before cutting 50 μm sections with a vibratome (VT-1000S, Leica). Free-floating sections were washed in 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS three times for 10 min, blocked in 10% donkey serum (Sigma) in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 h, and incubated with the following primary antibodies: anti-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, 5 μg/ml, cat. #OBT0030, Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation), anti-Ki-67 (1:500, MAB377, Millipore), anti-doublecortin (DCX, 1 μg/ml, cat. #SC-8066, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-dopamine transporter (DAT, 1:400, cat. #MAB369, Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents; Triton X-100 exposure in blocking phase only); anti-Caspase3 (6 μg/ml, cat. #AF355, R&D Systems), anti-GABA (44 μg/ml, #55545, Sigma), anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (1:500, cat. #ab113, AbCam), anti-Otx2 (1:400, cat. #AB9566, Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents), anti-Calbindin (1:500, cat. #C9848, Sigma), and anti-GIRK2 (1:500, cat. #APC-006, Alomone Labs). Sections were incubated with appropriate Alexa Fluor dye-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 h and washed three times for 10 min in PBS. Secondary antibodies alone were used as a control. Mounted sections were washed for 5 min in PBS and coverslipped using Aqua-Poly/Mount (Polysciences).

Bromodeoxyuridine immunohistochemistry.

Mice were injected with 300 mg of BrdU/kg 2 h before perfusion for 2 h pulse studies. This concentration was previously determined to label the maximal number of S-phase cells (Cameron and McKay, 2001). BrdU immunostaining of 50 μm sections was conducted as described previously (Luo et al., 2006) and analyzed by quantifying BrdU+ cells in 18 consecutive anterior forebrain sections from coordinates 0.5–1.4 mm anterior, relative to bregma.

Intensity analysis.

Average intensities of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) were calculated using ImageJ by sampling a 28 × 28 pixel area, in the dorsal and ventral SVZ, as well as in the corpus callosum and striatum, in 40× images taken from four consecutive sections from coordinates 1.10–1.25 mm anterior, relative to bregma. Values are reported as average intensity above background (corpus callosum) ± SD.

Whole mounts.

The entire lateral wall of the lateral ventricle was prepared as previously described and immunostained for doublecortin (DCX, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (Luo et al., 2006). Whole mounts were trimmed, placed onto glass slides, coverslipped with Aqua-Poly/Mount (Polysciences), and imaged by epifluorescence microscopy.

Neuronal tracing.

Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane in 2 L/min O2 flow while placed in a stereotaxic frame. Mice received a stereotaxic injection of 1 μl of 2 mg/ml wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to FITC (WGA-FITC; Sigma L-4895) and transport was analyzed after 5–7 d. For anterograde transport analysis, WGA-FITC was injected into the ventrolateral VTA region of the midbrain (−3.08 mm caudal, 0.4 mm lateral, 4.6 mm ventral, relative to bregma). For retrograde analysis, WGA-FITC was injected into the lateral ventricle (0.0 mm caudal, 0.9 mm lateral, 2.3 mm ventral, relative to bregma). We confirmed that 5–7 d was sufficient for retrograde transport of FITC via TH+ afferents to the midbrain. In addition, our observation of FITC+ cells in the raphé nucleus after 5–7 d, via retrograde transport by serotonergic neurons known to innervate the region of the SVZ (Lorez and Richards, 1982), served as a positive control. The extent of WGA-FITC diffusion into brain tissue following injection into the lateral ventricle was analyzed at 6 and 24 h after injection in the coronal sections containing the lateral and third ventricles. Needle insertion into the cortex (0.0 mm caudal, 0.9 mm lateral, 1.0 mm ventral, relative to bregma) revealed that 5–7 d later no WGA-FITC tracked to TH+ cells in the VTA. In addition to imaging for WGA-FITC, 50 μm sections were immunostained with antibodies for tyrosine hydroxylase, Otx2, Calbindin, and GIRK2. In the midbrain, FITC+ cells in six sections from −2.85 to −3.56 mm, relative to bregma, were counted and evaluated for coexpression of TH with Otx2, Calbindin, or GIRK2. Results are reported as percentage of the total FITC+ cells.

MPTP lesioning.

Mice received four intraperitoneal injections of 10 mg/kg 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) (Sigma) or 0.9% saline at 2 h intervals followed by eight intraperitoneal injections of 50 mg/kg BrdU, at 6 h intervals, as previously described (Höglinger et al., 2004). Animals were analyzed 3 d after the first MPTP injection.

Midbrain analysis.

SNpc and VTA midbrain neurons were characterized by TH, Otx2, Calbindin, and GIRK2 expression, and counted using stereological methods. SNpc and VTA regions in every third section from −2.85 to −3.56 mm relative to bregma were traced and cells were counted using MicroBrightField stereological algorithms and settings as follows: counting frames were 50 × 50 in a 150 × 150 grid. Fifty-micrometer sections (cut thickness) were used and safety zones were set to exclude edge areas such that 30 μm in the center of the section were counted. Results are reported based on mean measured thickness.

Microscopy and statistical analysis.

Sections were imaged on an Axioskop 2 mot plus microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging), using a Retiga 1300 EX digital camera (Q-Imaging), on a TCS SP2 confocal laser scan microscope (Leica), or on an Axio Imager M2 with Apotome (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) using a Orca R2 (Hamamatsu). Statistical results are reported as mean ± SD. Differences in means were assessed using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Dopaminergic afferents are retained in the SVZ following loss of SNpc neurons

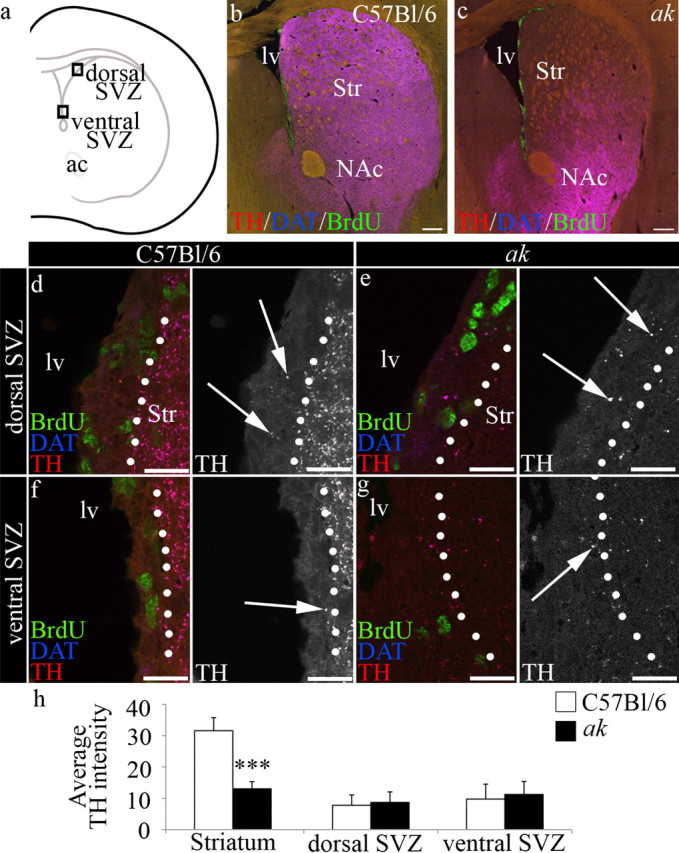

Several studies, including investigations of patients with Parkinson's disease, have correlated SNpc A9 neuron loss with decreased SVZ proliferative function (Baker et al., 2004; Höglinger et al., 2004; O'Keeffe et al., 2009). However, VTA A10 dopaminergic neurons are also thought to innervate regions adjacent to the SVZ (Björklund and Dunnett, 2007). To determine the respective contributions of A9 and A10 midbrain dopaminergic neuron populations to the innervation and regulation of the SVZ, we evaluated the ak mouse strain, which is selectively deficient in A9 midbrain neurons (Hwang et al., 2003; Nunes et al., 2003). The ak mouse has greatly reduced expression of Pitx3, a homeobox transcription factor that facilitates the survival and differentiation of A9 dopamine neurons (Semina et al., 1997; Hwang et al., 2003; Nunes et al., 2003; van den Munckhof et al., 2003, 2006; Baker et al., 2004; Maxwell et al., 2005; Amano et al., 2009; Papanikolaou et al., 2009). Analysis of the midbrain of ak mice shows early degeneration of midbrain dopamine neurons from E14.5 through postnatal day 0 (Smidt et al., 2004). Both A9 and A10 dopaminergic neurons are born in the ak mouse embryo; however, nearly all A9 dopamine neurons die during late embryonic development, while A10 neurons are relatively spared (Hwang et al., 2003, 2009; Nunes et al., 2003). Similar to the work of others (Beeler et al., 2009), we found that TH+ and DAT+ dopamine neuron afferents were significantly reduced in the striatum of ak mice, compared to C57BL/6 control mice (Fig. 1a–c). However, high-powered magnification revealed that afferents containing TH, the rate-limiting enzyme in the production of dopamine, were still found in the region of the SVZ in ak mice (Fig. 1d–h). Specifically, we found that TH+ neuronal afferents remained in both the dorsal and ventral regions of the SVZ in ak mice.

Figure 1.

Dopamine afferents are severely depleted in the dorsal striatum, but retained within the SVZ of ak mice. a, Schematic indicating area evaluated. Boxes indicate position of dorsal and ventral regions of the SVZ used in d–g. b, TH+/DAT+ afferents (purple) are observed in the dorsal and ventral striatum and along the SVZ in C57BL/6 control mice. c, TH+/DAT+ afferents are severely reduced in the dorsal striatum, but retained in the region of the nucleus accumbens in ak mouse brain. BrdU+ cells (green) define the SVZ, which is located along the lateral wall of the lateral ventricle. d–g, High-magnification images of the SVZ (left of dotted line) from control and ak mice revealed that TH+ afferents (purple, arrows) are present in the dorsal (d, e) and ventral (f, g) SVZ. h, Average intensity of TH is significantly reduced in ak mice in the striatum (C57BL/6 n = 4, ak n = 4, p = 0.000232), but not in the dorsal SVZ or ventral SVZ. lv, Lateral ventricle; Str, striatum; NAc, nucleus accumbens. Scale bars: b, c, 250 μm; d–g, 50 μm.

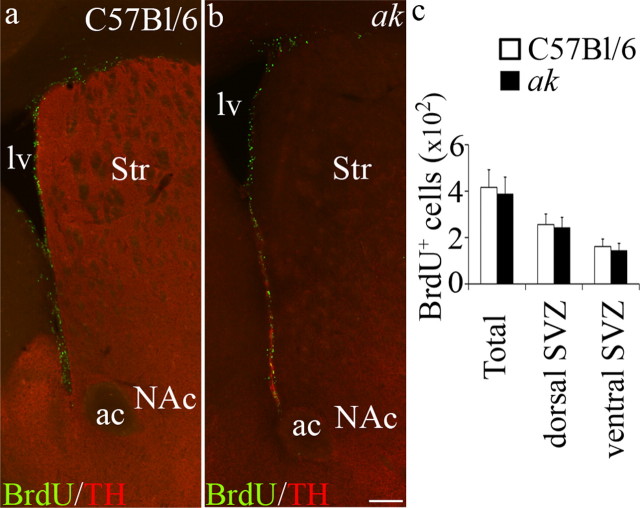

SNpc dopamine neuron loss does not affect SVZ cell proliferation or niche organization

We next examined whether the severe reduction in A9 nigrostriatal dopamine afferents affected SVZ proliferation in the ak mouse. Based on incorporation of the thymidine analog BrdU, we found that the number of dividing cells in the SVZ was not significantly different in 3-month-old ak compared to C57BL/6 control mice (C57BL/6 n = 10; ak n = 16; p = 0.34) (Fig. 2a–c). Similarly, no difference in proliferation levels was observed at either P7 or 6 months of age in ak compared to control mice (data not shown). As BrdU incorporation can also occur in dying cells, we quantified expression of caspase-3 and found that cell death levels were not significantly different in the SVZ of ak mice compared with controls (C57BL/6 31.83 ± 13.50, n = 6; ak 21.17 ± 10.91, n = 6; p = 0.163).

Figure 2.

SNpc A9 neuron deficiency does not affect proliferation in the SVZ of ak mice. Cell proliferation was quantified in the SVZ following a 2 h pulse BrdU injection. a–c, Based on incorporation of BrdU (green nuclei), levels of cell proliferation were similar in control and ak mice in both the dorsal and ventral SVZ. Ac, Anterior commissure; lv, lateral ventricle; Str, striatum; NAc, nucleus accumbens. Scale bars: a, b, 200 μm.

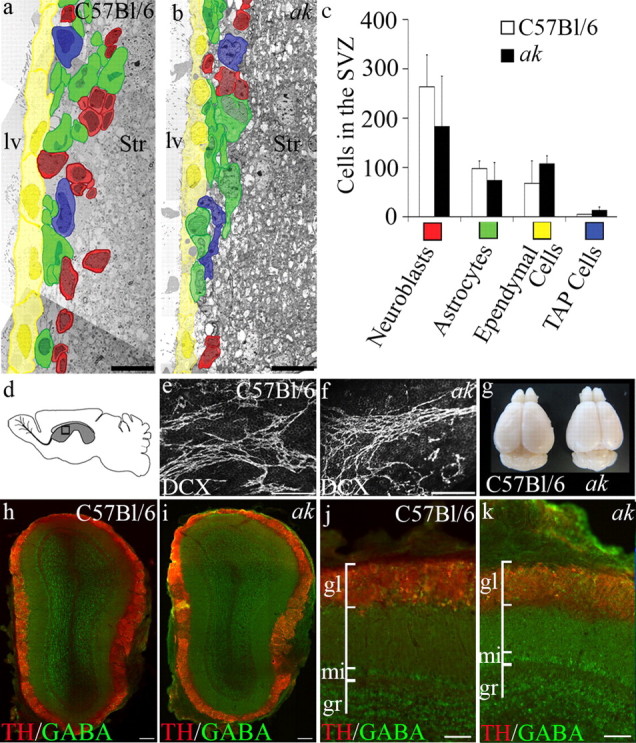

We also evaluated whether the absence of nigrostriatal A9 dopaminergic neurons affected either SVZ organization or the migratory capacity of newly generated neuroblasts. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to examine the cytoarchitectural organization of the SVZ in ak and control mice. Micrograph montages were prepared from 3-month-old ak and control mice, and cell types in the SVZ were identified and counted (Fig. 3a–c) (Luo et al., 2006). The SVZ contains four main cell types: astrocytes, a subset of which are stem cells; transit-amplifying progenitor (TAP) cells; neuroblasts, the highly migratory immature neurons; and ependymal cells that line the ventricles and form the apical border of the SVZ (Luskin, 1993; Doetsch et al., 1997). The numbers of neuroblasts, astrocytes, ependymal cells, and transit-amplifying cells in the young adult ak SVZ were not significantly different from C57BL/6 control mice (C57BL/6 n = 3; ak n = 3; neuroblasts p = 0.15, astrocytes p = 0.18, ependymal cells p = 0.11, transit-amplifying cells p = 0.06). Similarly, no significant differences in SVZ organization were observed in ak versus control mice at P7 or 6 months of age (data not shown).

Figure 3.

SNpc A9 neuron deficiency does not affect the SVZ of adult ak mice. a, b, Representative electron micrograph montages of the SVZ reveal the cellular composition and distribution of the four major cell types within the SVZ of C57BL/6 control and ak mice. SVZ cells are pseudo-colored to indicate cell type. c, Quantification of each of the major cell types of the SVZ revealed no significant difference between control and ak mice. d, Schematic indicating region of whole-mount preparation of lateral wall of the lateral ventricle (boxed area in gray region). e, f, Whole-mount preparations of doublecortin (DCX) immunolabeled neuroblast chains indicate no significant difference in neuroblast chain organization in control versus ak mice. g, Whole brains including olfactory bulbs from 3-month-old control and ak mice indicate no gross anomaly in ak brain morphology. h–k, Immunolabeling with GABA and TH indicate no deficits in olfactory bulb organization in ak mice. Gl, Glomerular region; mi, mitral cell region; gr, granule cell region; lv, lateral ventricle; Str, striatum. Scale bars: a, b, 10 μm; e, f, 200 μm; h, i, 200 μm; j, k, 100 μm.

Further analysis of SVZ functions included examination of the organization of neuroblasts into chains. Chain migration is the mechanism by which neuroblasts migrate across the lateral ventricle wall, along the RMS, and into the olfactory bulb (Lois et al., 1996; Wichterle et al., 1997). Neuroblasts were immunolabeled with doublecortin in whole-mount preparations of the lateral wall. The organization and number of chains of doublecortin+ neuroblasts transiting the lateral ventricle wall in ak mice did not differ from those found in control mice (Fig. 3d–f). Morphological observation revealed that the brains and, in particular, the olfactory bulbs of adult ak mice were comparable in size and morphology to control mice (Fig. 3g). In addition, no gross abnormalities were observed in adult olfactory bulb organization or composition (Fig. 3h–k). Together, these data demonstrate that despite an SNpc A9 neuron deficiency, ak mice retain full SVZ organization and function.

Dopaminergic neurons from the ventrolateral VTA innervate the SVZ

Since previous studies implicated SNpc A9 neurons in providing dopamine critical for normal SVZ regulation (Baker et al., 2004; Höglinger et al., 2004), we wondered how the ak mouse, which is deficient in A9 dopamine neurons, was able to maintain and regulate SVZ functions. We determined that dopamine neuron afferents were still present in the SVZ of ak mice (Fig. 1), yet the precise identity of these innervating neurons was unclear. To determine their origin, WGA conjugated to FITC was injected unilaterally into the lateral ventricle, using stereotaxic coordinates, of both C57BL/6 control and ak mice (Fig. 4). Retrograde tracking of labeled neurons was performed 5–7 d later.

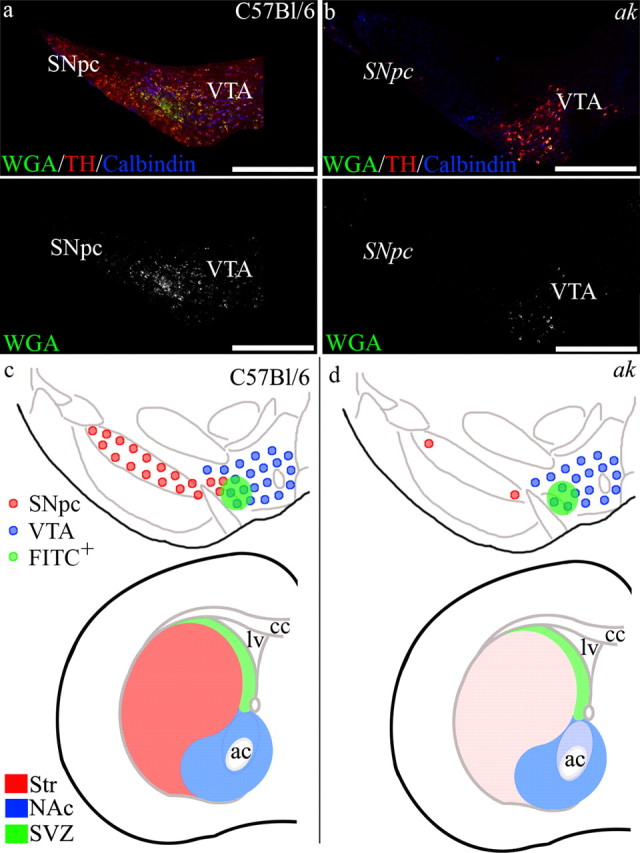

Figure 4.

The SVZ is innervated by dopaminergic neurons originating from the ventrolateral region of the VTA. WGA conjugated to FITC was unilaterally injected into the lateral ventricle, and after 5–7 d, the midbrain was analyzed for WGA-FITC retrograde tracking. a, In control mice, FITC-labeled neurons were found in the ventrolateral region of the VTA bordering the SNpc, with some FITC+ cells in regions of the SNpc. b, Retrograde tracking of WGA-FITC from the SVZ of ak mice also revealed FITC+ cells in the ventrolateral region of the VTA. (Note the absence of TH+ neurons in the area of the SNpc in ak mice.) c, d, Schematic of midbrain dopaminergic neuron populations that innervate the striatum and nucleus accumbens, modified from Björklund and Dunnett (2007). Here we represent midbrain dopamine neuron populations that innervate the striatum, nucleus accumbens, and SVZ in C57BL/6 control mice (c) and in ak mice (d). In ak mice, SNpc innervation of the striatum is depleted, while midbrain dopaminergic neuron innervation of the NAc and SVZ remains. ac, Anterior commissure; cc, corpus callosum; lv, lateral ventricle. Scale bars: a, b, 500 μm.

In control C57BL/6 mice, WGA was transported via SVZ afferents to cell bodies found in a discrete midbrain region at the ventrolateral border of the VTA, adjacent to the SNpc (Fig. 4a,c). In A9-deficient ak mice, retrograde tracking from the SVZ revealed similar tracking of WGA-FITC to midbrain cells located at the ventrolateral border of the VTA, immediately adjacent to where the SNpc would typically be found (Fig. 4b,d).

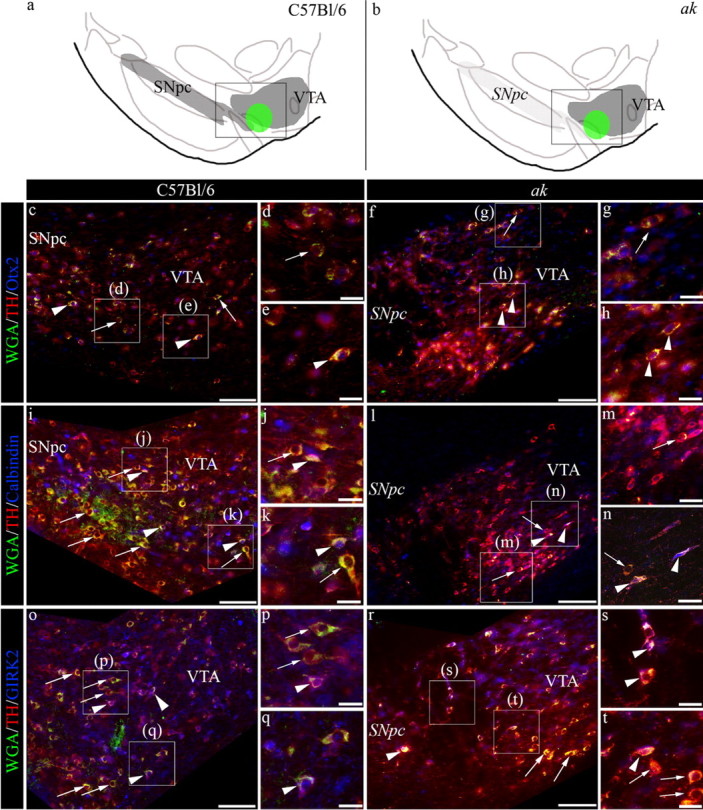

Based on transcriptome comparisons, several markers have been identified that are differentially expressed between the A9 and A10 dopaminergic neuron populations. A10 neurons that populate the VTA express significantly higher levels of ortho-denticle-related homeobox 2 (Otx2) and Calbindin, while A9 neurons that populate the SNpc express higher levels of G-protein coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channel 2 (GIRK2), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (AHD2), and glycosylated dopamine transporter (glyco-Dat) (C. Y. Chung et al., 2005, 2010; S. Chung et al., 2005; Di Salvio et al., 2010). To define the neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA, we combined retrograde tracking with immunohistochemical characterization in both C57BL/6 and ak mice (see Fig. 5a,b, schematic representation of midbrain region). Following 5–7 d of retrograde transport, quantification of FITC+ cells in C57BL/6 control mice revealed that 96% of the FITC+ cells were TH+. Of those FITC+ cells expressing TH, 46% coexpressed Otx2 (Fig. 5c–e, Table 1) and 22% coexpressed Calbindin (Fig. 5i–k, Table 1), while 41% coexpressed GIRK2 (Fig. 5o–q, Table 1). In the ak mouse, quantification of the FITC+ cells following 5–7 d of retrograde transport showed that 99% were TH+, with 63% coexpressing Otx2 (Fig. 5f–h, Table 1), 31% coexpressing Calbindin (Fig. 5l–n, Table 1), and 39% coexpressing GIRK2 (Fig. 5r–t, Table 1). In the A9-deficient ak mouse, these results indicate that the midbrain neurons that innervate the SVZ include a mixed population of Otx2+, Calbindin+, and GIRK2+ neurons that reside along the ventrolateral border of the VTA. Our studies also emphasize that the classification of midbrain dopamine neurons into A9 and A10 populations based on expression of markers such as Calbindin or GIRK2 alone is overly simplified. In the SNpc-deficient ak mouse, we observed GIRK2 expression in the VTA consistent with previous studies that have found low levels of GIRK2 expression in A10 populations and low levels of Calbindin expression in A9 populations (C. Y. Chung et al., 2005). While relative levels of proteins such as GIRK2 and Calbindin are presently used to identify A9 and A10 populations, there is not yet a distinct biomarker for either population (C. Y. Chung et al., 2005).

Figure 5.

Characterization of midbrain dopaminergic neurons that innervate the SVZ. a, b, Schematic representation of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain. Inset boxes indicate area imaged in c–t. In control and ak mice, FITC+ neurons were identified following retrograde transport of WGA-FITC. Immunostaining resulted in cells that were TH+/Otx2+ (arrowheads) and TH+/Otx2− (arrows) (c–h); TH+/Calbindin+ (arrowheads) and TH+/Calbindin− (arrows) (i–n); and TH+/GIRK2+ (arrowheads), as well as TH+/GIRK2− (arrows) (o–t). In the ak mouse midbrain, the italicized SNpc denotes the area typically populated by SNpc A9 neurons. Scale bars: c, f, i, l, o, r, 100 μm; others, 25 μm.

Table 1.

Classification of FITC+ cells in the midbrain following retrograde transport in C57Bl/6 and ak mice

| C57BL/6 (n = 3) | ak (n = 3) | |

|---|---|---|

| TH+ | 96.89 ± 3.73 | 99.15 ± 1.48 |

| TH+/Otx2+ | 46.15 ± 6.61 | 63.17 ± 10.42 |

| TH− | 3.11 ± 3.73 | 0.85 ± 1.48 |

| TH+ | 88.88 ± 6.03 | 97.58 ± 2.04 |

| TH+/Calbindin+ | 21.52 ± 7.03 | 31.27 ± 7.24 |

| TH− | 11.12 ± 6.03 | 2.42 ± 2.04 |

| TH+ | 94.31 ± 3.06 | 90.67 ± 4.82 |

| TH+/GIRK2+ | 41.12 ± 7.30 | 39.17 ± 5.48 |

| TH− | 5.69 ± 3.06 | 9.33 ± 4.82 |

Data are recorded as percentage of FITC+ cells ± SD, n = 3 per experimental grouping.

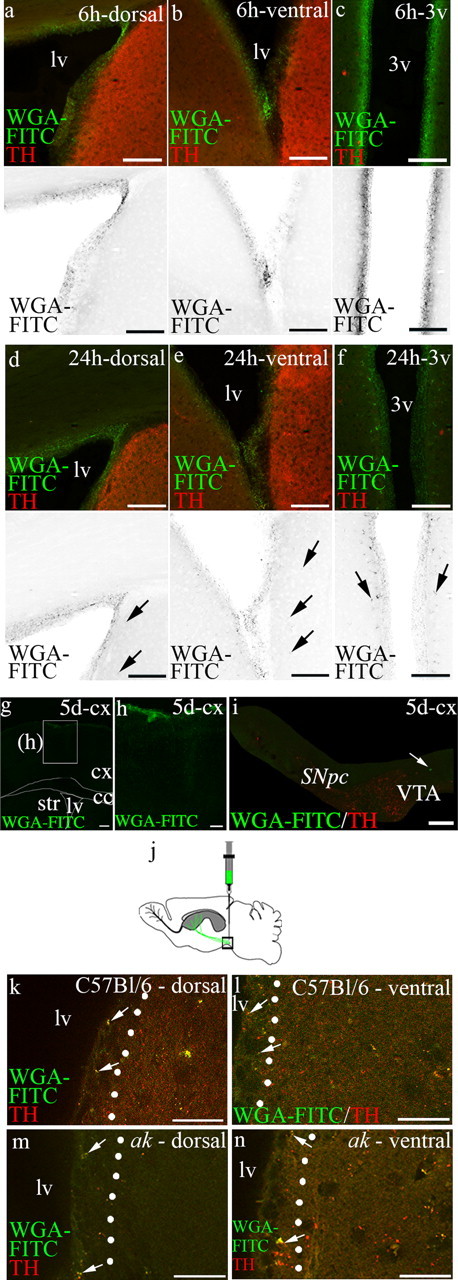

To assess the extent to which WGA-FITC diffuses into regions neighboring the SVZ, we examined coronal sections of the anterior forebrain at the level of the lateral ventricle at 6 and 24 h after injection. At 6 h, WGA-FITC was largely restricted to the ependyma and the subependyma of the lateral ventricle (Fig. 6a,b). We also determined that WGA-FITC is restricted to the ependyma in sections including the third ventricle (Fig. 6c). By 24 h, WGA-FITC intensity decreased significantly along the walls of both the lateral and third ventricles due to ventricular clearance. Only very faint staining was evident beyond the SVZ (Fig. 6d–f). This faint staining may represent the initial transport of WGA-FITC by SVZ afferents. These studies confirm that WGA-FITC diffusion into tissue neighboring the SVZ is very limited.

Figure 6.

Transport of WGA-FITC following injection into the lateral ventricle and anterograde transport following injection of WGA-FITC into the ventrolateral region of the VTA. a–f, The initial diffusion of WGA-FITC was analyzed at 6 and 24 h following injection into the lateral ventricle. a–c, Six hours after injection of WGA-FITC into the lateral ventricle revealed trace in the ependymal and subependymal regions. Similarly, WGA-FITC was found primarily associated with the ependyma in the third ventricle. d–f, At 24 h after injection, the intensity of WGA-FITC labeling was reduced, but restricted to the ependyma and subependyma. Some FITC+ afferents were detected beyond the SVZ (arrows). Monochrome images are shown below fluorescent images. g–i, Insertion of the needle into the cortex resulted in minimal WGA-FITC label in the cortex and no WGA-FITC labeling of TH+ neurons in the VTA. Arrow indicates WGA-FITC+/TH− cell. j–n, Anterograde transport was analyzed following injections into the ventrolateral VTA. j, Schematic depicting anterograde injection into ventrolateral VTA. k, l, In C57BL/6 control mice injection of WGA-FITC into the ventrolateral region of the VTA resulted in transport to afferents visible in the SVZ (arrows) in the dorsal and ventral SVZ. Transport of WGA-FITC to targets in both the medial striatum and nucleus accumbens can also be seen, as would be predicted by diffusion at the injection site and arborization of neuronal projections. m, n, Similarly, in the SNpc-deficient ak mouse, there was transport to both the dorsal and ventral SVZ (arrows). Transport of WGA-FITC to targets in the nucleus accumbens can also be seen. Lv, Lateral ventricle; 3v, third ventricle; cx, cortex; cc, corpus callosum; Str, striatum. Scale bars: a–f, 100 μm; g, 250 μm; h, 100 μm; i, 200 μm; k–n, 50 μm.

Midbrain WGA-FITC injection results in anterograde transport to the subventricular zone

Anterograde transport experiments allowed us to track midbrain dopaminergic neuron projections to the SVZ, providing further support of our retrograde tracing studies. WGA-FITC was stereotaxically injected into the region of the ventrolateral VTA of ak and control mice, and anterior forebrain sections were examined after 5–7 d. In C57BL/6 control mice, analysis of WGA-FITC in anterior forebrain sections revealed anterograde transport to both the dorsal and ventral SVZ (Fig. 6k,l). Similarly, in the SNpc-deficient ak mouse, anterograde transport of WGA-FITC resulted in labeled afferents in the dorsal and ventral SVZ (Fig. 6m,n). Together, these data reveal that a population of dopaminergic neurons, present in the SNpc-deficient ak mouse, innervates the SVZ.

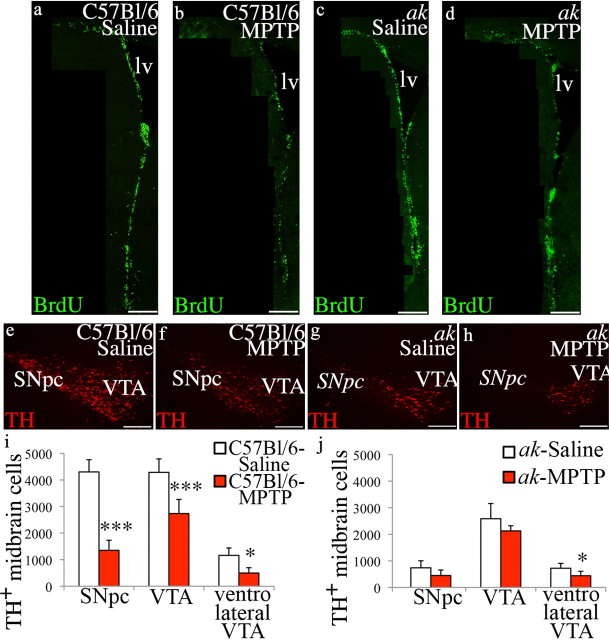

Chemical lesioning by MPTP affects dopamine neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA

The compound 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), the toxic metabolite of MPTP, is a neurotoxin that rapidly and selectively targets nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons (Langston et al., 1983). Reduction in SVZ proliferation following injection of MPTP has been attributed to the removal of A9 nigrostriatal midbrain neurons (Höglinger et al., 2004). Above, our results indicate that dopaminergic neuron tracts originating from a region at the ventrolateral border of the VTA innervate the SVZ. We sought to determine whether, in addition to depleting SNpc cells, MPTP exposure also reduces neurons in this ventrolateral VTA region. We administered MPTP to ak and control mice in a series of intraperitoneal injections. BrdU was injected immediately after the final MPTP injection (four injections at 6 h intervals) to label dividing cells, and the SVZ and midbrain were evaluated 3 d after the first MPTP injection (Höglinger et al., 2004). Quantification of the number of BrdU incorporating cells revealed that MPTP injection, compared to injection of vehicle alone, caused a significant decrease in the number of proliferating cells in the SVZ of both ak and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 7a–d). In C57BL/6 mice, proliferation was reduced by 36% [BrdU+ SVZ cells: saline (n = 4) 272.2 ± 40.64; MPTP (n = 6) 174.28 ± 52.11; p = 0.0135], similar to the levels reported previously (Höglinger et al., 2004), and we detected a 38% reduction in proliferating BrdU+ cells in ak mice [BrdU+ SVZ cells: saline (n = 4) 276.78 + 35.29; MPTP (n = 5) 170.70 ± 38.29; p = 0.00368]. Further analysis of the effects of MPTP exposure revealed a significant decline in SVZ proliferation in the dorsal SVZ compared to saline vehicle in both control and ak mice [dorsal SVZ % decline (MPTP-treated vs saline-treated): control 40.125%, p = 0.0105; ak 44.344, p = 0.00950]; whereas no significant decline was observed in the ventral SVZ of MPTP-treated versus saline vehicle-treated control and ak mice [ventral SVZ % decline (MPTP-treated vs saline-treated): control 28.909%, p = 0.067; ak 26.706, p = 0.110].

Figure 7.

MPTP exposure depletes midbrain dopamine neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA and decreases SVZ proliferation. a–d, Following MPTP administration, eight injections of BrdU at 6 h intervals were given to label dividing cells. After 3 d, proliferation in the SVZ was significantly reduced in both control and ak mice, compared to saline-injected mice. e, f, i, In control mice following exposure to MPTP, the number of TH+ neurons in the SNpc and the VTA, including neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA, were reduced (SNpc p = 3.86 × 10−6, VTA p = 1.73 × 10−3, ventrolateral VTA p = 0.0134). g, h, j, In ak mice, neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA were also reduced following MPTP injection, compared to saline-injected controls (p = 0.0462). lv, Lateral ventricle. Scale bars: a–d, 200 μm; e–h, 250 μm.

Analysis of the midbrain of MPTP-treated C57BL/6 mice revealed a loss of both SNpc and VTA neurons, including neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA (Fig. 7e,f). Specifically, in C57BL/6 mice, the neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA were reduced by 56%, compared to saline-injected controls (p = 0.0134) (Fig. 7i). In ak mice, neurons at the ventrolateral border of the VTA were reduced by 39% (p = 0.0462) (Fig. 7g,h,j). These results indicate that, in addition to depleting SNpc neurons, MPTP also targets neurons located in the ventrolateral VTA—precisely the population of neurons that innervates the SVZ.

Discussion

Examination of the SNpc-deficient ak mouse revealed no deficiencies in proliferation or organization in the SVZ, suggesting that dopamine neurons from another source supply sufficient dopamine to regulate the SVZ. Indeed, we report that a population of midbrain dopamine neurons in the ventrolateral VTA innervates the SVZ in both C57BL/6 control and ak mice and likely provides the SVZ with adequate access to the neurotransmitter dopamine. Although the traditional view of dopamine neuron anatomy is often expressed in terms of a clear distinction between the nigrostriatal system, which originates in the SNpc (A9) and terminates in the neostriatum, and the mesocorticolimbic system, which originates in the VTA (A10) and terminates in the ventral striatum and cortex, the present findings are consistent with the more complex view that the distinction between A9 and A10 projection zones is not so clear and that the VTA has a wide projection area that includes various cortical, limbic, and striatal regions (Beckstead et al., 1979; Fallon and Loughlin, 1995), as well as the SVZ. Likewise, the traditional view of dopamine function has been that the mesolimbic DA system mediates “reward” processes, while the nigrostriatal system regulates motor functions; this dogma also has been challenged, because the mesolimbic dopamine system is involved in multiple functions that span several realms, including motor control and learning, behavioral activation, and aversive as well as appetitive aspects of motivation (Salamone et al., 2007; Salamone, 2010). Our finding that the SVZ is innervated by midbrain dopamine neurons more generally associated with the VTA system indicates that mesolimbic dopamine signaling regulates SVZ neurogenesis. Thus, it is possible that the appetitive, aversive, or intense conditioned and unconditioned sensory stimuli that are generally thought to activate VTA dopamine neurons may also participate in the regulation of olfactory neurogenesis (Anstrom and Woodward, 2005; Salamone et al., 2007; Brischoux et al., 2009; Schultz, 2010). In view of the extended timescale for the process of SVZ neurogenesis and migration to the olfactory bulb, it is likely that dopaminergic regulation of the SVZ influences olfactory-based behavioral functions that fluctuate gradually over time. For example, seasonally based changes or maternal behavior may act to prime the olfactory system to alter long-term responsiveness to particular olfactory stimuli (Shepherd, 2004; Atanasova et al., 2008).

Retrograde tracing followed by biomarker immunoreactivity revealed that it is actually a mixed population of midbrain neurons that innervates the SVZ, including cells expressing GIRK2 and Calbindin. While expression of GIRK2 and Calbindin is thought to be indicative of A9 and A10 neurons, respectively, both proteins are expressed at varying levels in both neuron populations (i.e., higher concentrations of GIRK2/lower concentrations of Calbindin in SNpc neurons and vice versa for VTA dopaminergic neurons) (C. Y. Chung et al., 2005). While VTA neurons contribute to the innervation of the SVZ in ak mice, some SNpc dopaminergic neurons may also contribute to the SVZ in C57BL/6 mice. Future designation of midbrain dopaminergic neurons will need to be based on combinatorial studies that include retrograde tracking, as well as detection of multiple discriminating biomarkers that take into account the complexity of this region.

The ak mouse, which lacks SNpc dopaminergic neurons, provided evidence that a mixed population of VTA midbrain neurons contribute to the regulation of the SVZ. It is possible that this contribution had been overlooked previously due to the use of chemical lesion models that were thought to selectively ablate SNpc A9 neurons. In particular, MPTP, which is converted to MPP+ by MAO and is then preferentially transported via heightened expression of DAT into dopamine neurons (C. Y. Chung et al., 2005; Di Salvio et al., 2010), was considered to be specific for A9 SNpc neurons. In this study, we document that MPTP also depletes neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA. Following exposure to MPTP, the reduction in SVZ proliferation found in ak mice was similar to the reduction found in C57BL/6 control mice. Initially, this result was surprising as the ak mouse is largely deficient in SNpc A9 neurons and A9 dopamine neurons were thought to be responsible for modulating SVZ proliferation (Höglinger et al., 2004). Indeed, the effects of MPTP might have been expected to be of little consequence in the ak mouse due to reduced DAT expression in the remaining midbrain cells (Hwang et al., 2009). Instead, we found that a population of dopaminergic neurons associated with the VTA is also vulnerable to MPTP. Our finding that the SNpc-deficient ak mouse is susceptible to further midbrain dopaminergic neuron loss by MPTP emphasizes that midbrain dopamine neuron populations cannot be categorized into MPTP-vulnerable and MPTP-resistant groups based on A9 and A10 midbrain identity alone.

In addition to the targeting of neurons in the ventrolateral region of the VTA, it is important to note there are other factors that may contribute to the declines in SVZ proliferation observed following MPTP exposure. These include the reported direct effects of MPTP on proliferating SVZ cells due to the toxicity of MPTP and/or secondary effects due to acute cell loss in regions adjacent to the SVZ (He et al., 2008; Shibui et al., 2009). While a direct effect of MPTP on SVZ cells has been proposed, to date neither DAT nor monoamine transporters have been found to regulate MPTP-induced neuroblast apoptosis, and therefore the pathway through which MPTP may exert its direct effect on SVZ cells is currently unknown (He et al., 2008; Shibui et al., 2009). In addition, there is reported recovery of neuroblast numbers within 24 h of MPTP treatment, making this effect very transitory and the mechanism of recovery is unclear (He et al., 2008; Shibui et al., 2009). The data we collected was 3 d after MPTP treatment, after the transitory period of proposed neuroblast loss through a putative direct MPTP mechanism. This suggests that the effects we observed were not due to direct MPTP toxicity. In addition, our analysis revealed significant declines in dorsal but not ventral SVZ proliferating cells following MPTP treatment. Further characterization of the cells that reside in the VTA and SNpc, and analysis of the robustness of individual cells to neurotoxins, such as MPTP, together with analysis of the mechanism of action of MPTP will reveal how MPTP affects SVZ cells. In conclusion, our findings highlight the importance of using nonacute models, such as the ak mouse, in combination with neurotoxic agents and other pharmacological tools as a means to determine the precise role of dopamine signaling in SVZ function.

Ultimately, what is the significance of ventrolateral VTA dopamine neuron signaling to the SVZ? Maintenance of SVZ function throughout adulthood allows for continual replacement of olfactory bulb interneurons (Altman, 1969). This process is necessary for fine-discriminatory olfaction through adulthood. Declines in the neurogenic output of the SVZ and declines in olfactory capacity occur throughout aging, as well as in Parkinson's disease (Murphy et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2006; Atanasova et al., 2008). While the loss of SNpc dopamine neurons and subsequent motor dysfunction are hallmarks of Parkinson's disease, analysis of the midbrain from patients shows not only an average of 76% reduction in SNpc A9 neurons, but also declines of 48% in VTA A10 dopamine neurons (Hirsch et al., 1988). It is possible that the loss of A10 neurons is responsible for some of the nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease (Salamone et al., 2010), including those affecting olfaction.

Our results show that the SVZ is innervated by neurons residing in the ventrolateral region of the VTA. These neurons are maintained in the SNpc-deficient ak mouse, and we find that in these mice SVZ organization and function appear normal. MPTP lesioning depletes neurons in this midbrain region in both control and ak mice, and as a consequence SVZ cell proliferation is decreased. These findings indicate that a population of VTA dopaminergic neurons contributes to the regulation of SVZ-mediated olfactory neurogenesis throughout life. Loss of this population may be responsible for decreases in SVZ neurogenesis and loss of fine olfactory discrimination. This study provides the first evidence for a functional relationship between mesolimbic motivational processing and the regulation of olfactory bulb neurogenesis.

Footnotes

J.C.C. was supported by NINDS Grant NS05033. J.B.L. was supported in part by the Parkinson's Disease Foundation. We thank Drs. K. S. Kim and D. Y. Hwang (McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School) for the ak mice.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Altman J. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. IV. Cell proliferation and migration in the anterior forebrain, with special reference to persisting neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1969;137:433–457. doi: 10.1002/cne.901370404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. I. A longitudinal investigation of the kinetics, migration and transformation of cells incorporating tritiated thymidine in neonate rats, with special reference to postnatal neurogenesis in some brain regions. J Comp Neurol. 1966;126:337–389. doi: 10.1002/cne.901260302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Papanikolaou T, Sung LY, Lennington J, Conover J, Yang X. Nuclear transfer embryonic stem cells provide an in vitro culture model for Parkinson's disease. Cloning Stem Cells. 2009;11:77–88. doi: 10.1089/clo.2008.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstrom KK, Woodward DJ. Restraint increases dopaminergic burst firing in awake rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1832–1840. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasova B, Graux J, El Hage W, Hommet C, Camus V, Belzung C. Olfaction: a potential cognitive marker of psychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1315–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SA, Baker KA, Hagg T. Dopaminergic nigrostriatal projections regulate neural precursor proliferation in the adult mouse subventricular zone. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:575–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead RM, Domesick VB, Nauta WJ. Efferent connections of the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area in the rat. Brain Res. 1979;175:191–217. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bédard A, Parent A. Evidence of newly generated neurons in the human olfactory bulb. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;151:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler JA, Cao ZF, Kheirbek MA, Zhuang X. Loss of cocaine locomotor response in Pitx3-deficient mice lacking a nigrostriatal pathway. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1149–1161. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund A, Dunnett SB. Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brischoux F, Chakraborty S, Brierley DI, Ungless MA. Phasic excitation of dopamine neurons in ventral VTA by noxious stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4894–4899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Gould E. Adult neurogenesis is regulated by adrenal steroids in the dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 1994;61:203–209. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, McKay RD. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:406–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CY, Seo H, Sonntag KC, Brooks A, Lin L, Isacson O. Cell type-specific gene expression of midbrain dopaminergic neurons reveals molecules involved in their vulnerability and protection. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1709–1725. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CY, Licznerski P, Alavian KN, Simeone A, Lin Z, Martin E, Vance J, Isacson O. The transcription factor orthodenticle homeobox 2 influences axonal projections and vulnerability of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Brain. 2010;133:2022–2031. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Hedlund E, Hwang M, Kim DW, Shin BS, Hwang DY, Jung Kang U, Isacson O, Kim KS. The homeodomain transcription factory Pitx3 facilitates differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into AHD2-expressing dopaminergic neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover JC, Shook BA. Aging of the subventricular zone neural stem cell niche. Aging Dis. 2011;2:149–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Kam M, Nannmark U, Anderson MF, Axell MZ, Wikkelso C, Holtås S, van Roon-Mom WM, Björk-Eriksson T, Nordborg C, Frisén J, Dragunow M, Faull RL, Eriksson PS. Human neuroblasts migrate to the olfactory bulb via a lateral ventricular extension. Science. 2007;315:1243–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.1136281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong MR, Crutcher MD, Georgopoulos AP. Relations between movement and single cell discharge in the substantia nigra of the behaving monkey. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1599–1606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-08-01599.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Salvio M, Di Giovannantonio LG, Acampora D, Prosperi R, Omodei D, Prakash N, Wurst W, Simeone A. Otx2 controls neuron subtype identity in ventral tegmental area and antagonizes vulnerability to MPTP. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1481–1488. doi: 10.1038/nn.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, García-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cellular composition and three-dimensional organization of the subventricular germinal zone in the adult mammalian brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5046–5061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05046.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Caillé I, Lim DA, García-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JH, Loughlin SE. Substantia nigra. In: Paxinos G, editor. The rat nervous system. San Diego: Academic; 1995. pp. 215–255. [Google Scholar]

- Freundlieb N, François C, Tandé D, Oertel WH, Hirsch EC, Höglinger GU. Dopaminergic substantia nigra neurons project topographically organized to the subventricular zone and stimulate precursor cell proliferation in aged primates. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2321–2325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4859-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Reeves AJ, Fallah M, Tanapat P, Gross CG, Fuchs E. Hippocampal neurogenesis in adult Old World primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5263–5267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XJ, Yamauchi H, Uetsuka K, Nakayama H. Neurotoxicity of MPTP to migrating neuroblasts: studies in acute and subacute mouse models of Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds JW. Autoradiographic study of histogenesis in the mouse olfactory bulb. II. Cell proliferation and migration. J Comp Neurol. 1968;134:305–322. doi: 10.1002/cne.901340305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Graybiel AM, Agid YA. Melanized dopaminergic neurons are differentially susceptible to degeneration in Parkinson's disease. Nature. 1988;334:345–348. doi: 10.1038/334345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höglinger GU, Rizk P, Muriel MP, Duyckaerts C, Oertel WH, Caille I, Hirsch EC. Dopamine depletion impairs precursor cell proliferation in Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:726–735. doi: 10.1038/nn1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollerman JR, Schultz W. Dopamine neurons report an error in the temporal prediction of reward during learning. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:304–309. doi: 10.1038/1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DY, Ardayfio P, Kang UJ, Semina EV, Kim KS. Selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of Pitx3-deficient aphakia mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;114:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DY, Hong S, Jeong JW, Choi S, Kim H, Kim J, Kim KS. Vesicular monoamine transporter 2 and dopamine transporter are molecular targets of Pitx3 in the ventral midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurochem. 2009;111:1202–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science. 1983;219:979–980. doi: 10.1126/science.6823561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennington JB, Yang Z, Conover JC. Neural stem cells and the regulation of adult neurogenesis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:99. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Proliferating subventricular zone cells in the adult mammalian forebrain can differentiate into neurons and glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2074–2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, García-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Chain migration of neuronal precursors. Science. 1996;271:978–981. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorez HP, Richards JG. Supra-ependymal serotoninergic nerves in mammalian brain: morphological, pharmacological and functional studies. Brain Res Bull. 1982;9:727–741. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Daniels SB, Lennington JB, Notti RQ, Conover JC. The aging neurogenic subventricular zone. Aging Cell. 2006;5:139–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin MB. Restricted proliferation and migration of postnatally generated neurons derived from the forebrain subventricular zone. Neuron. 1993;11:173–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90281-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SL, Ho HY, Kuehner E, Zhao S, Li M. Pitx3 regulates tyrosine hydroxylase expression in the substantia nigra and identifies a subgroup of mesencephalic dopaminergic progenitor neurons during mouse development. Dev Biol. 2005;282:467–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Dayan P, Sejnowski TJ. A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive Hebbian learning. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1936–1947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01936.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Nondahl DM. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA. 2002;288:2307–2312. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes I, Tovmasian LT, Silva RM, Burke RE, Goff SP. Pitx3 is required for development of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4245–4250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230529100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keeffe GC, Tyers P, Aarsland D, Dalley JW, Barker RA, Caldwell MA. Dopamine-induced proliferation of adult neural precursor cells in the mammalian subventricular zone is mediated through EGF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8754–8759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803955106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolaou T, Amano T, Lennington J, Sink K, Farrar AM, Salamone J, Yang X, Conover JC. In-vitro analysis of Pitx3 in mesodiencephalic dopaminergic neuron maturation. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:2264–2275. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathania M, Yan LD, Bordey A. A symphony of signals conducts early and late stages of adult neurogenesis. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:865–876. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD. Involvement of nucleus accumbens dopamine in behavioral activation and effort-related functions. In: Iversen LL, Iversen SD, Dunnett SB, Björklund A, editors. Dopamine handbook. Oxford: Oxford UP; 2010. pp. 286–300. [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD, Correa M, Farrar A, Mingote SM. Effort-related functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine and associated forebrain circuits. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:461–482. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD, Correa M, Farrar AM, Nunes EJ, Collins LE. Role of dopamine/adenosine interactions in the brain circuitry regulating effort-related decision making: insights into pathological aspects of motivation. Future Neurol. 2010;5:377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Multiple functions of dopamine neurons. F1000 Biol Rep. 2010;2:2. doi: 10.3410/B2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semina EV, Reiter RS, Murray JC. Isolation of a new homeobox gene belonging to the Pitx/Rieg family: expression during lens development and mapping to the aphakia region on mouse chromosome 19. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2109–2116. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd GM. The human sense of smell: are we better than we think? PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibui Y, He XJ, Uchida K, Nakayama H. MPTP-induced neuroblast apoptosis in the subventricular zone is not regulated by dopamine or other monoamine transporters. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:1036–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smidt MP, Smits SM, Burbach JPH. Homeobox gene Pitx3 and its role in the development of dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0943-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Munckhof P, Luk KC, Ste-Marie L, Montgomery J, Blanchet PJ, Sadikot AF, Drouin J. Pitx3 is required for motor activity and for survival of a subset of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Development. 2003;130:2535–2542. doi: 10.1242/dev.00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Munckhof P, Gilbert F, Chamberland M, Lévesque D, Drouin J. Striatal neuroadaptation and rescue of locomotor deficit by L-dopa in aphakia mice, a model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2006;96:160–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H, García-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Direct evidence for homotypic, glia-independent neuronal migration. Neuron. 1997;18:779–791. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]