Abstract

Background

Iron deficiency has been proposed as a potential therapeutic target in heart failure, but its prevalence and association with anemia and clinical outcomes in community-dwelling adults with heart failure have not been well characterized.

Methods and Results

Using data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, we evaluated the associations between iron deficiency, hemoglobin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in 574 adults with self-reported heart failure. Iron deficiency was defined in both absolute and functional terms as a ferritin level < 100 μg/L or between 100 and 299 μg/L if the transferrin saturation was < 20%. Iron deficiency was present in 61.3% of participants and was associated with reduced mean hemoglobin (13.6 vs. 14.2 g/dl, p=.007) and increased mean CRP (0.95 vs. 0.63 mg/dl, p=.04). Over a median of 6.7 years of follow-up, there were 300 all-cause deaths, 193 of which were from cardiovascular causes. In age- and gender-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, hemoglobin, CRP, and transferrin saturation, but not iron deficiency, were significantly associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. In multivariate models, hemoglobin remained an independent predictor of cardiovascular mortality, while CRP remained an independent predictor of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Conclusions

Iron deficiency is common in heart failure and is associated with decreased hemoglobin and increased CRP. In multivariate analysis, hemoglobin was associated with cardiovascular mortality while CRP was associated with both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Iron deficiency was not associated with all-cause or cardiovascular mortality in this cohort.

Keywords: iron deficiency, inflammation, heart failure, mortality

Iron is an essential trace element that plays a role in oxygen transport, cellular respiration, immune system regulation, and protein transcription.1-4 Functional iron deficiency occurs when iron stores are trapped inside cells of the reticuloendothelial system, reducing iron availability to target tissues and organs, despite adequate iron stores in the body. While absolute iron deficiency is uncommon in heart failure patients, functional iron deficiency, mediated by activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in heart failure, may be much more common and may reduce functional capacity by decreasing iron-dependent oxygen transport and oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle.5-6

Iron deficiency is a potential therapeutic target in heart failure. Several small single-center studies have reported that parenteral repletion of iron in heart failure patients with iron deficiency anemia improves exercise capacity and quality of life.7-10 A larger multicenter trial demonstrated that parental repletion of iron in heart failure patients with functional iron deficiency improved exercise capacity and quality of life, independent of the presence of anemia.11 Functional iron deficiency has also been reported to be associated with increased mortality risk, independent of the presence of anemia, in patients with advanced systolic heart failure referred to specialized care centers.6 Whether iron deficiency is an independent predictor of mortality in community-dwelling heart failure patients is unknown.

Accordingly, we sought to characterize the prevalence, clinical correlates, and independent prognostic significance of iron deficiency in a representative sample of U.S. civilian non-institutionalized adults with self-reported heart failure who participated in the NHANES III survey.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

This is a prospective cohort study of adults with self-reported heart failure in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).12 Baseline data was collected from 1988-1994 as a cross-sectional, complex, multi-stage survey of a representative sample of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population. NHANES III oversampled non-Hispanic blacks, Mexican Americans, and persons over the age of 60 to obtain reliable information about these subgroups. Individuals aged ≥ 17 (n=20,050) received a home-based interview; 17,705 of these participants were examined in the mobile examination center (MEC). Follow-up on vital status and cause of death were obtained from the NHANES III Linked Mortality File, which linked participants to information obtained from death certificate data in the National Death Index (NDI).13

Responses to demographic, lifestyle, dietary, and medical history questions were gathered by trained professionals during the household and MEC surveys. During the MEC exam, a physical exam was performed and blood was drawn. We included participants ≥ 17 years of age who were examined in the MEC and who identified themselves as having heart failure by a “yes” response to the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you had congestive heart failure?” Iron deficiency was defined in both absolute and functional terms, as it included participants with a ferritin level < 100 μg/L or between 100 and 299 μg/L if the transferrin saturation was < 20%.11

Sample Demographics, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and Comorbid Conditions

We obtained information on age, gender, race-ethnicity, education, and income from the NHANES III household adult survey data. Race-ethnicity was self-reported and classified as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, and other. Education was categorized as did not complete high school, completed high school only, or obtained at least some higher education. Poverty income ratio, the ratio between the midpoint of the observed family income category (<$10,000, $10,000-29,999, $30,000-49,999, and ≥$50,000) and the poverty threshold produced annually by the Census Bureau, allowed income to be analyzed uniformly across the entire survey period. Smoking status was dichotomized as current smokers and former or never smokers. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight measured at the MEC examination. It was analyzed as both a continuous variable and as a categorical variable dichotomized into obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and non-obese (BMI < 30 kg/m2).14 Physical activity was classified as vigorous, moderate, light, or sedentary from the frequency and intensity of leisure time exercise.15

Blood pressures were measured in the interview by a trained interviewer and in the MEC examination by a physician, and an average of up to six values for systolic and diastolic blood pressures were recorded. Hypertension was defined by self-reported diagnosis, self-reported antihypertensive medication use, mean systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg, or mean diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg. Total cholesterol (mg/dl), triglyceride (mg/dl), high density lipoprotein (HDL, mg/dl), CRP (mg/dl), ferritin (μg/L), transferrin saturation (%), hemoglobin (g/dl), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c, %), sodium (mmol/L), and creatinine (mg/dl) levels were obtained from blood collected during the MEC examination using methods described by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.16 Ferritin was measured by using Bio-Rad Laboratories’ Quantimune Ferritin Immunoradiometric Assay (IRMA) kit, which was a single-incubation, two-site assay using a radiolabeled I-125 antibody to ferritin. Not all participants had low density lipoprotein (LDL) measurements, and as such LDL was not included in the analysis. Hyperlipidemia was defined by self-reported high cholesterol, self-reported cholesterol-lowering medication use, or total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dl. Diabetes was defined by self report or baseline HbA1c measurement ≥ 7% on MEC examination. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin < 12.5 g/dl. Diagnoses of other comorbid conditions such as myocardial infarction (MI) and cancer were obtained by self-report. Neither B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) nor N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) were measured in NHANES III.

Outcome Variables

Person-months of follow-up from the MEC examination date were obtained from the Linked Mortality File. Mortality follow-up was complete through December 31, 2000, with the exception of one participant who was lost to follow-up. All-cause mortality was defined by the final determination of vital status by the National Center for Health Statistics using a probabilistic match between NHANES III and National Death Index death certificate data. Cardiovascular mortality was determined from the death certificate data by pooling cause of death codes from the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death (ICD-10).17 Cardiovascular disease mortality included codes for deaths from all major cardiovascular diseases (ICD-10 codes I00-I78), including ischemic heart disease, stroke, and other cardiovascular disorders.

Statistical Analysis

Among participants with self-reported heart failure, baseline characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, and comorbid conditions were compared between participants with iron deficiency and those without iron deficiency using survey procedures in SAS 9.2 (Statistical Analysis System, Cary, NC).18 Unadjusted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates stratified by the presence or absence of iron deficiency along with p values were obtained by a life table product limit method. Kaplan-Meier curves for both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality were determined for the dichotomous iron deficiency variable and the equality of curves was tested by a log-rank statistic. To evaluate the association between iron deficiency and mortality, we fit age- and gender-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models. Similarly, we fit age- and gender-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models for 1 g/dl decreases in hemoglobin, 1 mg/dl increases in CRP, 25 μg/L decreases in ferritin, and 1% decreases in transferrin saturation. Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered significant. The final multivariate Cox proportional hazards models for iron deficiency included age, gender, hemoglobin, CRP, BMI, and self-reported MI.

The complex sample survey design of NHANES III included stratification, clustering, and unequal weighting of participants in order to estimate characteristics for the entire population. In order to account for this complex survey design, we used survey procedures (Proc Surveymeans, Proc Surveyfreq, Proc Surveyreg, and Proc Surveyphreg) in SAS that allowed us to incorporate these in the analysis.18,19 Specifically, a strata statement was used to account for the stratified nature of the sampling procedure in NHANES III. Because NHANES III also used cluster sampling to group together sampling units, we included a cluster statement in the survey procedures. Finally, to provide accurate population-based estimates, participants in NHANES III were weighted unequally in the survey design to better represent the target population. This was accounted for by using a weight statement in the final survey procedures.20 All of the survey weights, strata, and cluster variables were provided in the NHANES III database and linked to each individual participant.

Results

There were 574 participants with self-reported heart failure and available laboratory studies. Iron deficiency was present in 352 participants (61.3%). Anemia was present in 96 participants (16.7%). Iron deficiency was more common in participants with anemia compared to those without anemia (73.2% vs. 56.4%, p=.05). Participants with iron deficiency were more likely to be anemic than participants without iron deficiency (20.2% vs. 10.7%, p=.06). Participants with iron deficiency were more likely to be female (60.1% vs. 34.9%, p<.001), less likely to be obese (29.0% vs. 41.8%, p=.01), and less likely to self-report a history of MI (50.2% vs. 65.0%, p=.03) than participants without iron deficiency. Iron deficiency was associated with lower mean hemoglobin (13.6 vs. 14.2 g/dl, p=.007) and higher mean CRP (0.95 vs. 0.63 mg/dl, p=.04) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants with heart failure stratified by iron deficiency.*

| All with HF (n = 574) |

HF but not ID (n = 222) |

HF and ID (n = 352) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.3 (63.0-67.5) | 64.1 (61.1-67.1) | 66.1 (63.2-68.9) | 0.32 |

| Male, % | 50.2 (43.5-56.9) | 65.1 (56.1-74.2) | 39.9 (33.4-46.4) | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.89 | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 71.2 (64.0-78.4) | 71.5 (58.7-84.4) | 70.9 (63.4-78.5) | |

| White, % | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black, % |

13.0 (9.7-16.2) | 14.5 (10.4-18.6) | 11.9 (8.0-15.9) | |

| Mexican American, % |

5.6 (4.1-7.1) | 4.4 (2.8-6.0) | 6.5 (4.3-8.6) | |

| Other, % | 10.2 (3.1-17.4) | 9.6 (0.0-21.6) | 10.7 (2.4-18.9) | |

| Smoker, % | 21.5 (14.7-28.2) | 22.9 (10.0-35.8) | 20.5 (13.7-27.3) | 0.73 |

| Education | 0.13 | |||

| Less than high school, % |

54.6 (48.3-60.9) | 49.7 (39.2-60.2) | 60.0 (50.8-65.1) | |

| High school graduate, % |

21.8 (16.5-27.2) | 28.0 (16.9-39.1) | 17.5 (13.2-21.8) | |

| Beyond high school, % |

23.6 (18.1-29.0) | 22.2 (14.3-30.2) | 24.5 (17.9-31.1) | |

| Poverty income ratio | 2.31 (2.11-2.50) | 2.48 (2.15-2.82) | 2.17 (1.96-2.38) | 0.11 |

| Obese, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

34.2 (27.6-40.9) | 41.8 (33.7-49.8) | 29.0 (21.1-36.9) | 0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.6 (27.7-29.5) | 29.5 (28.4-30.7) | 28.0 (26.9-29.0) | 0.02 |

| Activity level | 0.31 | |||

| Sedentary, % | 47.2 (40.2-54.1) | 40.8 (30.3-51.3) | 51.5 (43.8-59.3) | |

| Light, % | 20.5 (16.4-24.5) | 20.8 (13.4-28.1) | 20.3 (15.4-25.1) | |

| Moderate, % | 29.5 (23.8-35.2) | 34.2 (24.1-44.2) | 26.3 (19.5-33.1) | |

| Vigorous, % | 2.9 (0.5-5.2) | 4.2 (0.0-8.9) | 1.9 (0.0-4.5) | |

| Systolic BP, mean mmHg |

138.6 (136.1- 141.0) |

136.9 (132.7- 141.2) |

139.7 (136.5- 143.0) |

0.32 |

| Diastolic BP, mean mmHg |

73.2 (71.5-74.9) | 73.9 (71.3-76.6) | 72.8 (71.0-74.5) | 0.41 |

| Hypertension, % | 72.0 (66.0-78.0) | 68.6 (56.9-80.3) | 74.4 (68.3-80.5) | 0.36 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl |

223.3 (216.9- 229.7) |

219.8 (209.6- 230.0) |

225.8 (217.3- 234.2) |

0.38 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 201.2 (180.7- 221.8) |

188.6 (163.2- 213.9) |

210.0 (179.5- 240.6) |

0.29 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 46.5 (44.3-48.6) | 45.9 (42.2-49.5) | 46.9 (44.6-49.2) | 0.60 |

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 73.4 (66.7-80.8) | 68.7 (57.2-80.3) | 77.3 (71.1-83.5) | 0.11 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 0.82 (0.64-1.00) | 0.63 (0.50-0.75) | 0.95 (0.67-1.24) | 0.04 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 13.9 (13.6-14.1) | 14.2 (13.8-14.6) | 13.6 (13.3-13.9) | 0.007 |

| Anemia, % | 16.3 (10.2-22.4) | 10.7 (3.2-18.3) | 20.2 (13.3-27.1) | 0.06 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 6.01 (5.85-6.18) | 5.89 (5.63-6.14) | 6.10 (5.85-6.35) | 0.26 |

| Diabetes, % | 22.1 (18.0-26.2) | 22.7 (17.8-27.7) | 21.7 (15.1-28.3) | 0.83 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 140.7 (140.3- 141.1) |

141.0 (140.4- 141.6) |

140.5 (139.9- 141.0) |

0.18 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.34 (1.22-1.46) | 1.40 (1.17-1.64) | 1.30 (1.21-1.39) | 0.37 |

| Myocardial Infarction, % |

56.2 (49.2-63.3) | 65.0 (54.3-75.7) | 50.2 (41.6-58.8) | 0.03 |

| Cancer, % | 7.7 (4.4-11.0) | 7.9 (3.2-12.6) | 7.6 (4.1-11.1) | 0.91 |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 157.0 (131.7- 182.4) |

270.3 (219.9- 320.6) |

78.8 (70.0-87.6) | <0.001 |

| Transferrin saturation, % |

24.5 (22.1-26.8) | 31.8 (27.8-35.9) | 19.4 (17.9-20.8) | <0.001 |

Continuous variables are given as means while categorical variables are given as percentages. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are given in parentheses. Data is reported as population estimates using survey weights, strata, and cluster variables. The first column reports data for the entire heart failure population while the remaining columns report data stratified by presence or absence of iron deficiency.

HF, heart failure; ID, iron deficiency; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

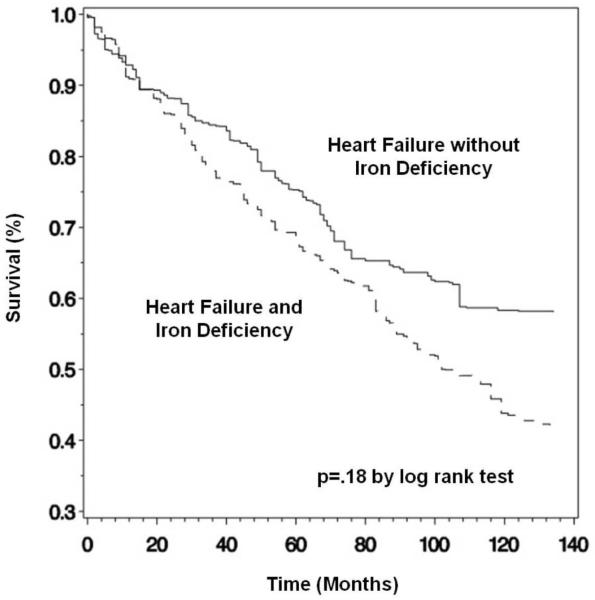

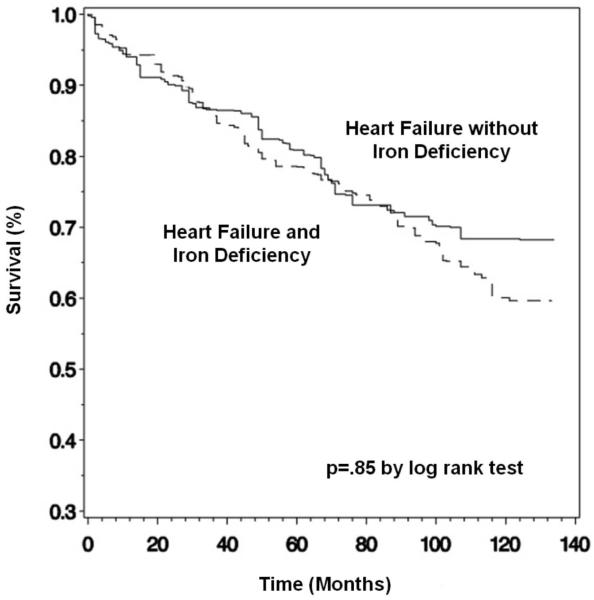

Of the 574 participants with heart failure, 273 (47.6%) were alive through the follow-up period and 300 (52.3%) died, 193 (33.6%) from cardiovascular causes. One participant was lost to follow-up. Mean follow up time was 6.7 (6.2-7.2) years. Unadjusted mortality rates in participants with and without iron deficiency did not differ (Table 2 and Figures 1 and 2). To further evaluate the association between iron deficiency and mortality while controlling for important confounders, Cox proportional hazards models were used; relative risks were reported as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (Table 3). In age- and gender-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, a 1 g/dl decrease in hemoglobin was associated with higher all-cause [1.16 (1.01-1.33), p=.03] and cardiovascular [1.19 (1.02-1.37), p=.02] mortality, a 1 mg/dl increase in CRP was associated with higher all-cause [1.24 (1.12-1.37), p<.0001] and cardiovascular [1.20 (1.07-1.34), p=.002] mortality, and a 1% decrease in transferrin saturation was associated with higher all-cause [1.03 (1.01-1.05), p=.01] and cardiovascular [1.02 (1.00-1.04), p=.03] mortality. In a multivariate model that included all of the variables from Table 1 that were significantly different in participants with and without iron deficiency, the estimate of the association between hemoglobin and cardiovascular mortality did not substantially change [1.20 (1.01-1.43), p=.04], while the estimate of the association between hemoglobin and all-cause mortality was no longer statistically significant [1.16 (0.99-1.35), p=.06]. The estimate of the association between CRP and mortality did not substantially change and remained statistically significant for both all-cause [1.22 (1.10-1.35), p<.0001] and cardiovascular [1.17 (1.04-1.32), p=.01] mortality. The estimate of the association between transferrin saturation and mortality was not longer significant both for all causes and for cardiovascular causes. In both the age- and gender-adjusted and the multivariate models, iron deficiency was not associated with all-cause or cardiovascular mortality.

Table 2.

All-cause and cardiovascular mortality among adults with heart failure, stratified by iron deficiency status.

| All HF (n = 574) |

HF but not ID (n = 222) |

HF and ID (n = 352) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause deaths | ||||

| Number* (%) | 300 (52.3) | 110 (49.5) | 190 (54.0) | 0.33 |

| Population estimate†,% | 48.4 (41.5-55.4) | 42.6 (31.1-54.1) | 52.5 (44.9-60.1) | 0.16 |

| Cardiovascular deaths | ||||

| Number* (%) | 193 (33.6) | 80 (36.0) | 113 (32.1) | 0.33 |

| Population estimate†,% | 31.9 (26.1-37.8) | 32.0 (22.4-41.5) | 31.9 (25.3-38.6) | 0.99 |

| Mortality rates‡ | ||||

| All-cause | 72.2 | 61.4 | 80.1 | 0.18 |

| Cardiovascular | 47.6 | 46.1 | 48.7 | 0.85 |

HF, heart failure; ID, iron deficiency.

All-cause and cardiovascular deaths are presented as the total number of deaths as well as the percentage of participants deceased on follow-up. The first column reports data for the entire cohort of participants with heart failure while the remaining columns report data stratified by presence or absence of iron deficiency.

Population estimates of the percentage of participants deceased on follow-up are reported using survey weights, strata, and cluster variables. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for these population estimates are given in parentheses.

Mortality rates per 1,000 person-years of follow-up are presented unadjusted for confounders. Data is reported as population estimates using survey weights, strata, and cluster variables.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of survival for all-cause mortality, stratified by presence or absence of functional iron deficiency.*

*Kaplan-Meier curves are presented unadjusted for confounders, using survey weights, strata, and cluster variables to obtain population estimates.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of survival for cardiovascular mortality, stratified by presence or absence of functional iron deficiency.*

*Kaplan-Meier curves are presented unadjusted for confounders, using survey weights, strata, and cluster variables to obtain population estimates.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards ratios with 95% confidence intervals for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.*

| Age- and Gender-Adjusted | Multivariate | |

|---|---|---|

| All-Cause Mortality | ||

| Hemoglobin | 1.16 (1.01-1.33), p=.03 | 1.16 (0.99-1.35), p=.06 |

| CRP | 1.24 (1.12-1.37), p<.0001 | 1.22 (1.10-1.35), p<.0001 |

| Iron Deficiency | 1.22 (0.87-1.71), p=.25 | 1.12 (0.80-1.57), p=.50 |

| BMI | 1.00 (0.97-1.04), p=.95 | 1.01 (0.97-1.05), p=.68 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 0.76 (0.54-1.07), p=.12 | 0.79 (0.56-1.11), p=.17 |

| Ferritin | 0.99 (0.96-1.02), p=.61 | 0.99 (0.96-1.03), p=.73 |

| Transferrin Saturation | 1.03 (1.01-1.05), p=.01 | 1.02 (0.99-1.04), p=.13 |

| Cardiovascular Mortality | ||

| Hemoglobin | 1.19 (1.02-1.37), p=.02 | 1.20 (1.01-1.43), p=.04 |

| CRP | 1.20 (1.07-1.34), p=.002 | 1.17 (1.04-1.32), p=.01 |

| Iron Deficiency | 1.02 (0.68-1.55), p=.91 | 0.95 (0.63-1.43), p=.81 |

| BMI | 1.01 (0.96-1.06), p=.85 | 1.01 (0.96-1.08), p=.63 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 0.65 (0.40-1.05), p=.08 | 0.65 (0.40-1.06), p=.08 |

| Ferritin | 0.99 (0.97-1.02), p=.62 | 0.99 (0.97-1.02), p=.71 |

| Transferrin Saturation | 1.02 (1.00-1.04), p=.03 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03), p=.20 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; BMI, body mass index.

The multivariate predictors used in the Cox models included age, gender, hemoglobin, CRP, BMI (as a continuous variable), and iron deficiency. In the Cox models for ferritin and transferrin saturation, iron deficiency was excluded from the multivariate models (as it was defined using these variables) but the remaining predictors were included. All hazard ratios and confidence intervals incorporated survey weights, strata, and cluster variables to obtain population estimates. The hazard ratios presented above reflect 1 g/dl decreases in hemoglobin, 1 mg/dl increases in CRP, 1 kg/m2 increases in BMI, 25 μg/L decreases in ferritin, and 1% decreases in transferrin saturation. Iron deficiency is a categorical variable.

Finally we tested the prognostic significance of more restrictive definitions of iron deficiency, analyzing low ferritin levels independent of transferrin saturation levels. 9.8% of the participants had a ferritin level < 30 μg/L, while 47.2% of the participants had a ferritin level < 100 μg/L. Neither a ferritin level < 30 μg/L [all-cause hazard ratio (HR) 0.84 (0.51-1.40), p=.51, cardiovascular HR 0.93 (0.49-1.76), p=.81] nor a ferritin level < 100 μg/L [all-cause HR 1.18 (0.82-1.70), p=.38, cardiovascular HR 0.92 (0.60-1.41), p=.71] were associated with increased mortality.

Discussion

This population-based study demonstrates that iron deficiency is common in adults with self-reported heart failure.6 This study also confirmed that decreases in hemoglobin are associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in adults with self-reported heart failure,5,21-26 though this association did not remain statistically significant for all-cause mortality in the multivariate model. This study also confirmed the association of CRP with increased mortality in adults with self-reported heart failure,27-30 an association that remained significant in the multivariate model. This study demonstrated cross-sectional associations between functional iron deficiency and both anemia and inflammation, findings that are consistent with the putative pathophysiology of iron deficiency in heart failure.1,26,31-33 Contrary to the findings of a recently published observational study,6 we did not observe a significant association between iron deficiency and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality in community-dwelling adults with self-reported heart failure.

Proposed mechanisms for anemia in heart failure include insufficient erythropoietin secretion (due in part to inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system), erythropoietin resistance (due to chronic inflammation), hemodilution, comorbid kidney disease, and iron deficiency.1 Iron deficiency in and of itself may also be multifactorial, though inflammation appears to be one of the key mediators of iron deficiency and the subsequent progression to anemia in heart failure.1,34 Proinflammatory cytokines have been shown to lead to decreased intestinal absorption of iron and sequestration of iron in macrophages.34 The mechanism is related to that observed in anemia of chronic disease.35 CRP is an inflammatory marker that is known to be elevated in heart failure and carries prognostic significance;27-30 in addition CRP demonstrates an inverse relationship to hemoglobin.36 The effects of chronic inflammation and iron deficiency may be detrimental prior to the onset of full-blown anemia, as iron deficiency in and of itself is associated with decreased aerobic capacity and abnormal oxygen transport in skeletal muscle, independent of the presence of anemia.1 Our research supports the hypothesis that inflammation mediates the link between iron deficiency and anemia, as participants with iron deficiency tended to have higher average CRP levels and lower hemoglobin levels, with nearly double the risk of full-blown anemia.

Our study had several important limitations. Our observational prospective study design does not fully allow causal inference, as unmeasured confounders or other biases may have contributed to our results. NHANES III did not collect data on BNP or NT-proBNP; as such we were unable to use this value as a corroborator of volume status in our cohort. We also did not have data available on medications used by the participants in the study; as such we were unable to determine if participants were taking medications with proven efficacy in heart failure. Other than the observed high event rate, the available data did not allow us to objectively substantiate the diagnosis of heart failure. As the diagnosis of heart failure was obtained by self-report, it may be subject to self-report biases. However, the event rates were consistent with a mild heart failure population, as several recent studies have noted an annual mortality for class I-II heart failure around 5-7%.37-38 Given that our data were collected from a representative sample of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population, it is plausible that these were mostly highly functional and ambulatory patients with less advanced disease and survival comparable to the recently studied mild heart failure populations. Compared to the results presented by Jankowska et al.6 in patients with advanced systolic heart failure referred to tertiary heart failure treatment centers, our participant pool may have been healthier overall. This is supported by the fact that our population had a lower mean CRP, higher mean BMI, and lower frequency of diabetes and myocardial infarction compared to the population studied by Jankowska et al. In addition, the relatively high mean systolic BP, large proportion of women, and age of the population indicated that many of our participants had preserved ejection fraction. As such, it is possible that iron deficiency may not fully retain its prognostic value in healthier heart failure patients with varying degrees of systolic function. This appears to be consistent with the finding by Jankowska et al. that functional iron deficiency is associated with higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class; as such iron deficiency may have a higher prognostic significance in patients falling into higher NYHA functional classes than the ambulatory, community-dwelling participants in this study.

The presented analysis also has several important strengths. First, this is the first study looking at the prevalence of iron deficiency specifically in a community-dwelling population of US adults with self-reported heart failure. Second, a population-based representative sample was surveyed, allowing estimates of usually underrepresented groups such as minorities and the elderly. Third, data were collected using a standardized, detailed, labor-intensive process with rigorous quality control. Fourth, because data were collected in a nonmedical setting for research purposes, there was little missing data and less chance of subject response bias. Fifth, because subjects were randomly selected from different geographic regions across the country, these results are potentially generalizable to the entire US population of community-dwelling adults with heart failure. Lastly, the use of a hard endpoint such as all-cause mortality as the primary outcome variable reduces the likelihood of spurious results.

Though there is evidence that parental repletion of iron in heart failure patients with functional iron deficiency independent of the presence of anemia improves exercise capacity and quality of life,11 there is also evidence that moderately increased iron stores without overt evidence of organ dysfunction may be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.39 This association may in part be explained by the iron-dependent formation of free hydroxyl radicals that can damage cells irreversibly and promote reperfusion injury, leading to possible relationships between iron overload and carcinogenesis and atherogenesis.39-40 Blood donation is known to deplete total body iron stores and is associated with reduced cardiovascular risk in blood donor populations.41-44 Currently available biomarkers of iron stores provide limited information on tissue iron stores and regulation of intracellular iron stores. These limitations may have led to misclassification of the true iron storage status in our population and obscured our ability to detect a difference in mortality between the groups with and without iron deficiency. An ongoing prospective study of the effects of parenteral iron therapy on clinical outcomes in the heart failure population will provide important additional data to assess the potential causal role of iron in disease progression.

In conclusion, iron deficiency is common in community-dwelling adults with heart failure and is associated with markers of anemia and inflammation. Our data do not support a direct relationship between iron deficiency and mortality in community-dwelling US adults with self-reported heart failure. Further work is needed to determine the long-term effects of iron therapy in the heart failure population.

Iron deficiency has been proposed as a potential therapeutic target in heart failure. Recentresearch has characterized the prevalence of iron deficiency in symptomatic heart failure patients referred to tertiary care centers, but the prevalence in the community-dwelling population of U.S. adults with heart failure remains unclear. Recent research has also demonstrated that iron deficiency may be associated with mortality in symptomatic heart failure patients referred to tertiary care centers; iron supplementation in these patients may be associated with improved exercise tolerance and quality of life. Our study characterizes the prevalence of iron deficiency in ambulatory, community-dwelling U.S. adults with self-reported heart failure, and demonstrates cross-sectional associations with both anemia and inflammation. Our study also suggests that iron deficiency is not associated with mortality in this population. Our results suggest that though iron repletion may be a useful strategy in symptomatic patients with advanced heart failure to improve symptoms and quality of life, iron repletion appears less important in patients with less advanced heart failure and milder symptoms. Our study thus adds to the emerging body of literature regarding the management of iron deficiency in heart failure patients, and provides useful data for clinicians caring for ambulatory, community-dwelling patients with heart failure.

Acknowledgements

We obtained public-use NHANES III data from the National Center of Health Statistics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This material was presented in abstract form at the 14th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, 13 September 2010, San Diego, CA. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the supporting agencies or of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Sources of Funding We are grateful for the support provided by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (AI 60373, CA 74015, CA 069222, and GM 29745) and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (RCD 00-211 and IIR 04-170).

Footnotes

Disclosures Dr. Katz has served as a consultant for Amgen, Inc. Amgen, Inc had no relationship or financial contribution to the research presented above. None of the remaining authors have any financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jelani Q, Attanasio P, Katz SD, Anker SD. Treatment with iron of patients with heart failure with and without anemia. Heart Failure Clin. 2010;6:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Failla ML. Trace elements and host defense: recent advances and continuing challenges. J Nutr. 2003;133:1443S–1447S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1443S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordeuk VR, Bacon BR, Brittenham GM. Iron overload: causes and consequences. Annu Rev Nutr. 1987;7:485–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.07.070187.002413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beard JL. Iron biology in immune function, muscle metabolism, and neuronal functioning. J Nutr. 2001;131:568S–580S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.568S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang YD, Katz SD. Anemia in chronic heart failure: prevalence, etiology, clinical correlates, and treatment options. Circulation. 2006;113:2454–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jankowska EA, Rozentryt P, Witkowska A, Nowak J, Hartmann O, Ponikowska B, Borodulin-Nadzieja L, Banasiak W, Polonski L, Filippatos G, McMurray J, Anker SD, Ponikowski P. Iron deficiency: an ominous sign in patients with systolic chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1872–1880. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolger AP, Bartlett FR, Penston HS, O’Leary J, Pollock N, Kaprielian R, Chapman CM. Intravenous iron alone for the treatment of anemia in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1225–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toblli JE, Lombrana A, Duarte P, Di Gennaro F. Intravenous iron reduces NT-pro-brain natriuretic peptide in anemic patients with chronic heart failure and renal insufficiency. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1657–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okonko DO, Grzeslo A, Witkowski T, Mandal A, Slater RM, Roughton M, Foldes G, Thum T, Majda J, Banasiak W, Missouris CG, Poole-Wilson PA, Anker SD, Ponikowski P. Effect of intravenous iron sucrose on exercise tolerance in anemic and nonanemic patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure and iron deficiency. FERRIC-HF: a randomized, controlled, observer-blinded trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Usmanov RI, Zueva EB, Silverberg DS, Shaked M. Intravenous iron without erythropoietin for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with moderate to severe congestive heart failure and chronic kidney insufficiency. J Nephrol. 2008;21:236–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anker SD, Colet J Comin, Filippatos G, Willenheimer R, Dickstein K, Drexler H, Luscher TF, Bart B, Banasiak W, Niegowska J, Kirwan BA, Mori C, von Eisenhart Rothe B, Pocock SJ, Poole-Wilson PA, Ponikowski P. Ferric carboxymaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2436–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 1988-1994. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics; [Accessed January 3, 2011]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nh3data.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Health Statistics. Office of Analysis and Epidemiology . Public-use Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Linked Mortality File, 2007. Hyattsville, MD: [Accessed January 3, 2011]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/data_linkage/mortality/nhanes3_linkage_public_use.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1855–1867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford ES. Does exercise reduce inflammation? Physical activity and C-reactive protein among U.S. adults. Epidemiology. 2002;13:561–568. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunter EW, Lewis BG, Koncikowski SM, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [Accessed January 3, 2011];Laboratory procedures used for the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 1988-1994. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes3/cdrom/nchs/manuals/labman.pdf.

- 17.International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Tenth Revision. Volume 1. World Health Organization; 1992. Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAS/STAT User’s Guide. Version 9.2. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukhopadhyay PK. SAS Global Forum Proceedings: Statistics and Data Analysis. Seattle, WA: 2010. Not Hazardous to Your Health: Proportional Hazards Modeling for Survey Data with the SURVEYPHREG Procedure; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT ® 9.2 User’s Guide. SAS Publishing; Cary, NC: 2008. Chapter 14. Introduction to Survey Sampling and Analysis Procedures. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Ahmad A, Rand WM, Manjunath G, Konstam MA, Salem DN, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ. Reduced kidney function and anemia as risk factors for mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:955–962. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mozaffarian D, Nye R, Levy WC. Anemia predicts mortality in severe heart failure: the prostective randomized amlodipine survival evaluation (PRAISE) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1933–1939. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horwich TB, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, MacLellan WR, Borenstein J. Anemia is associated with worse symptoms, greater impairment in functional capacity, and a significant increase in mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1780–1786. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosiborod M, Smith GL, Radford MJ, Foody JM, Krumholz HM. The prognostic importance of anemia in patients with heart failure. Am J Med. 2003;114:112–119. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maggioni AP, Opasich C, Anand I, Barlera S, Carbonieri E, Gonzini L, Tavazzi L, Latini R, Cohn J. Anemia in patients with heart failure: prevalence and prognostic role in a controlled trial and in clinical practice. J Card Fail. 2005;11:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ezekowitz JA, McAlister FA, Armstrong PW. Anemia is common in heart failure and is associated with poor outcomes: insights from a cohort of 12,065 patients with new-onset heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:223–225. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052622.51963.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller C, Laule-Killian K, Christ A, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Perruchoud AP. Inflammation and long-term mortality in acute congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2006;151:845–850. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chirinos JA, Zambrano JP, Chakko S, Schob A, Veerani A, Perez GO, Mendez AJ. Usefulness of C-reactive protein as an independent predictor of death in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:88–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anand IS, Latini R, Florea VG, Kuskowski MA, Rector T, Masson S, Signorini S, Mocarelli P, Hester A, Glazer R, Cohn JN, for the Val-HeFT Investigators C-reactive protein in heart failure: prognostic value and the effect of valsartan. Circulation. 2005;112:1428–1434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.508465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Araujo JP, Lourenco P, Azevedo A, Frioes F, Rocha-Goncalves F, Ferreira A, Bettencourt P. Prognostic value of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in heart failure: a systematic review. J Card Fail. 2009;15:256–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witte KK, Desilva R, Chattopadhyay S, Ghosh J, Cleland JG, Clark AL. Are hematinic deficiencies the cause of anemia in chronic heart failure? Am Heart J. 2004;147:924–930. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westenbrink BD, Voors AA, van Veldhuisen DJ. Is anemia in chronic heart failure caused by iron deficiency? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2301–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berry C, Norrie J, Hogg K, Brett M, Stevenson K, McMurray JJ. The prevalence, nature, and importance of hematologic abnormalities in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1313–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anand IS. Anemia and chronic heart failure: implications and treatment options. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:501–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1011–1023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anand IS, Rector T, Deswal A. Relationship between proinflammatory cytokines and anemia in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:485. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang ASL, Wells GA, Talajic M, Arnold MO, Sheldon R, Connolly S, Hohnloser SH, Nichol G, Birnie DH, Sapp JL, Yee R, Healey JS, Rouleau JL. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2385–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zannad F, McMurray JJV, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, Vincent J, Pocock SJ, Pitt B. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jelani Q, Katz SD. Treatment of anemia in heart failure: potential risks and benefits of intravenous iron therapy in cardiovascular disease. Cardiology in Review. 2010;18:240–250. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181e71150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan XM, Li W. Iron involvement in multiple signaling pathways of atherosclerosis: a revisited hypothesis. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2157–2172. doi: 10.2174/092986708785747634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuomainen TP, Salonen R, Nyyssonen K, Salonen JT. Cohort study of relation between donating blood and risk of myocardial infarction in 2682 men in eastern Finland. BMJ. 1997;314:793–794. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyers DG, Strickland D, Maloney PA, Seburg JK, Wilson JE, McManus BF. Possible association of a reduction in cardiovascular events with blood donation. Heart. 1997;78:188–193. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Blood donations and the risk of coronary heart disease in men. Circulation. 2001;103:52–57. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyers DG, Jensen KC, Menitove JE. A historical cohort study of the effect of lowering body iron through blood donation on incident cardiac events. Transfusion. 2002;42:1135–1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]