Abstract

Objective

Cigarette smoking and unhealthy alcohol use are common causes of preventable morbidity and mortality that frequently result in admission to an intensive care unit. Understanding how to identify and intervene in these conditions is important because critical illness may provide a “teachable moment.” Furthermore, the Joint Commission recently proposed screening and receipt of an intervention for tobacco use and unhealthy alcohol use as candidate performance measures for all hospitalized patients. Understanding the efficacy of these interventions may help drive evidence-based institution of programs, if deemed appropriate.

Data Sources

A summary of the published medical literature on interventions for unhealthy alcohol use and smoking obtained through a PubMed search.

Summary

Interventions focusing on behavioral counseling for cigarette smoking in hospitalized patients have been extensively studied. Several studies include or focus on critically ill patients. The evidence demonstrates that behavioral counseling leads to increased rates of smoking cessation but the effect depends on the intensity of the intervention. The identification of unhealthy alcohol use can lead to brief interventions. These interventions are particularly effective in trauma patients with unhealthy alcohol use. However, the current literature would not support routine delivery of brief interventions for unhealthy alcohol use in the medical ICU population.

Conclusion

ICU admission represents a “teachable moment” for smokers and some patients with unhealthy alcohol use. Future studies should assess the efficacy of brief interventions for unhealthy alcohol use in medical ICU patients. In addition, identification of the timing and optimal individual to conduct the intervention will be necessary.

“The doctor of the future will give no medicine but will interest his patients in the care of the human frame, in diet, and in the cause and prevention of disease.” - Thomas Edison

Introduction

More than one-fifth of the annual deaths in the United States are attributable to cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption. Despite recent public health efforts, annual healthcare expenditures for these conditions exceed $100 billion and mortality rates remain essentially unchanged (1–5). Unfortunately, these treatable conditions lead to frequent encounters with critical care providers. Involvement of critical care providers in screening and initiating treatment for tobacco smoking and unhealthy alcohol use is important because admission to the ICU may represent a “teachable moment” wherein patients feel vulnerable and are willing to change their behaviors. We will review the data on the identification of hospitalized and critically ill patients who smoke or have unhealthy alcohol use. Subsequently, we discuss the controversies that surround the utilization of interventions during their hospital stay and whether these therapies can improve morbidity and mortality following discharge, thus leading to secondary prevention. While most studies of intervention focus on hospitalized patients, many successfully incorporate critically ill patients into systematic screening and intervention.

We searched PubMed from 1970 until 2010 for published work relevant to this subject. We entered the terms “brief intervention,” “counseling,” “behavioral counseling,” “intensive counseling,” and “behavioral therapy” into a search. These terms were then grouped together, identifying over 100,000 articles. We then entered search terms specific to unhealthy alcohol use and smoking and individually cross-matched them with intervention or counseling-related articles. We focused on articles published in the past 10 years. Additionally, the references of retrieved articles were reviewed and we selected additional articles deemed to be relevant.

Brief Interventions, Motivational Interviewing, and a “Teachable Moment”

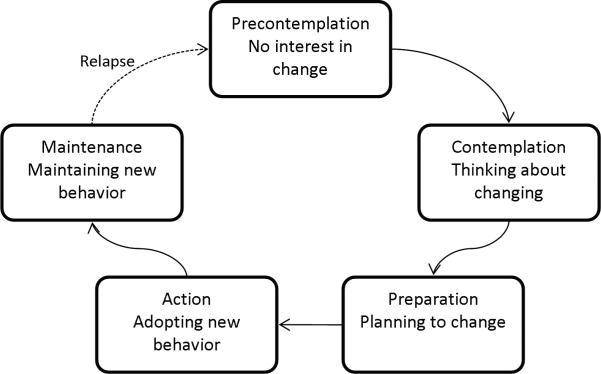

Brief interventions (BIs) refer to 10 to 15 minute sessions in which healthcare professionals (e.g. physicians, nurses, social workers, or psychologists) provide counseling, feedback, advice, and goal-setting (6). Brief interventions have been applied to a number of risky behaviors including cigarette smoking and problem drinking (7). When risky behaviors are identified during a clinical encounter, a BI may be a “teachable moment” for the patient regardless of whether the patient is seeking help for that particular problem (8). While there is no consensus as to the content, BIs frequently incorporate the techniques of motivational interviewing (MI) developed by Miller for the treatment of substance abuse (9). MI is patient-centered, builds trust, and focuses on increasing readiness to change. Readiness to change is classified into five stages based on the transtheoretical model (Figure 1). The techniques of MI include reflective listening and eliciting motivational statements from patients by exploring both sides of a patient's ambivalence (7). An important component of MI is empathy on the part of the healthcare provider. Alcohol consumption one year following the delivery of a brief intervention using MI is inversely correlated to the amount of empathy expressed by the physician (10). Conversely, confrontational approaches have a deleterious correlation with the amount of alcohol consumption at 12 months (11).

Figure 1.

The Transtheoretical Model describes a sequence of steps in successful behavior change using stages of change. Patients may not move through the stages in a linear manner and may relapse.

In studies of interventions for cigarette smoking or unhealthy alcohol use that include ICU patients, the intervention is generally delivered following the resolution of critical illness but prior to discharge home (12–15). Although interventions have been successfully implemented in critically ill patients, potential barriers exist. Some of these barriers are well-described in the outpatient or emergency department setting and several may be applicable to the ICU. Healthcare providers perceive a lack of time (16) as well as a lack of knowledge and confidence in providing appropriate treatments as barriers to implementation (17). While healthcare providers fear that addressing sensitive issues with patients will upset them (18), patients are generally positive about screening (19). A perceived lack of time as well as a lack of confidence in identification and treatment can and have been overcome in the outpatient clinic as well as in the hospital setting (18, 20). However, future studies will need to address these barriers in the ICU.

Cigarette Smoking

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States and is responsible for 443,000 annual deaths (21). After a period of steady decline, smoking rates have reached an unfortunate plateau for the last 5 years with 20.6% of the US population being current smokers in 2009 (22). To address this epidemic, current guidelines from the United States Department of Health and Human Services recommend that every healthcare provider screen patients for tobacco use at each encounter (23). A 2004 report from the Surgeon General concluded that epidemiologic evidence was sufficient to link smoking with multiple diseases that commonly result in ICU admission (24). The prevalence of smoking in ICU patients is 22–46% in prospective studies where smoking rates are reported. These studies reveal that critical care providers encounter current smokers at a higher rate than the general population (25–28). Similarly, epidemiologic studies strongly link smoking with an increased risk and duration of hospitalization. Importantly, this risk is attenuated in former smokers highlighting the potential benefits of smoking cessation (29–31)

Diagnosis and Identification

The National Health Interview Survey is used to estimate annual smoking rates in the United States and defines a current smoker as somebody who has smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smokes every day or almost every day (32). Although any amount of smoking is considered detrimental to health, there are formal criteria for the diagnosis of nicotine dependence established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (DSM IV) and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10) (33). Withdrawal symptoms, difficulty controlling use, higher prioritization of nicotine use, and persistent use despite detrimental effects are central to the diagnostic criteria. In the only study to assess smoking history in critically ill patients, 21% of non-smokers identified by history obtained from a patient, surrogate, or the medical chart were determined to be current smokers by levels of serum cotinine or urine 4-(methylnitosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (34). While diagnostic tools for the identification of current smokers in the ICU require further study, all patients who are identified as smokers should be offered smoking cessation therapy.

Treatment

The first step in offering treatment for smoking cessation is to ask about tobacco use. This is emphasized in a brief intervention framed by the “5 A's” model of treating tobacco use and dependence advocated by guidelines from the U.S. Surgeon General (Table 1) (23). Unfortunately, studies demonstrate that documented smoking histories are only obtained in 66–75% of hospitalized patients (35–36). Identification of current smokers is important because only 20–30% of smokers who make a quit attempt utilize therapies proven to double or triple abstinence rates (37). Once a current smoker has been identified in the hospital, tobacco use or dependence should be added to the admission problem list and a brief intervention should be performed. However, a brief intervention is only effective when combined with more intensive behavioral counseling for hospitalized patients (38–39).

Table 1.

The “5 A's” model for treating tobacco use and dependence (Revised from reference 14).

| Action | Strategy for Implementation | |

|---|---|---|

| Ask about tobacco use | Identify and document tobacco use status for every patient at every visit. | Incorporate tobacco use into the vital signs. |

| Advise to quit | In a clear, strong, and personalized manner, urge every tobacco user to quit. |

Clear – “It is important that you quit smoking now, and I can help you.” Strong – “As your clinician, I need you to know that quitting smoking is the most important thing you can do to protect your health now and in the future.” Personalized – Tie tobacco use to current symptoms and health concerns, and/or its social and economic costs. |

| Assess willingness to make a quit attempt | Is the tobacco user willing to make a quit attempt at this time? | If willing, provide assistance or refer for intensive counseling If unwilling, provide an intervention shown to increase future attempts. |

| Assist in quit attempt | For patient willing to make a quit attempt, provide or refer for counseling and offer medication when appropriate. |

Preparation - Help patient set a quit date, tell family, anticipate challenges, and remove tobacco from their environment. Medication - Recommend medications when indicated. Counseling – Emphasize abstinence, discuss past quit experiences, anticipate challenges, avoid alcohol, encourage housemates to quit. Support and supplementary materials – Provide supportive clinical environment, information on quitlines. |

| Arrange follow-up | Arrange for follow-up contacts either in person or via telephone. |

Timing – soon after quit date. Actions – identify problems, congratulate abstinence, anticipate challenges. |

Behavioral counseling in support of a quit attempt for a hospitalized smoker has been studied in numerous randomized controlled trials. There are typically three components of behavioral counseling: skills training, intra-treatment social support, and extra-treatment social support (40–41). In most studies conducted in hospitalized patients, a brief intervention is delivered by a physician. Follow-up behavioral counseling is then delivered by a nurse who is typically a member of the study team (39, 42–44). The techniques of motivational interviewing and the concepts of the transtheoretical model discussed above are frequently incorporated into smoking cessation counseling for hospitalized patients (45–47). A recent systematic review of 27 studies assessing the efficacy of behavioral counseling found that its efficacy is based on intensity (Table 2). Two of these studies explicitly excluded ICU patients (45, 48), three focused on ICU patients (12–14), and the remainder do not explicitly exclude ICU patients. Only studies that included intensive counseling with more than 1 month of follow-up post-discharge had a statistically significant effect, with a 65% increase in the odds of successful smoking cessation (49). Although many of the studies were conducted in patients with cardiovascular disease, the effect of intensive counseling on smoking cessation persisted regardless of admission diagnosis and was also independent of the provision of pharmacotherapy. In addition to increasing the rate of smoking cessation, intensive interventions may also decrease the rate of re-hospitalization and improve mortality (50).

Table 2.

Behavioral Counseling for smoking cessation. The pooled effects of 27 studies of behavioral counseling for smoking cessation in hospitalized patients.

| Successful Cessation in Intervention | Successful Cessation in Control | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity 1 * | 68/678 | 59/673 | 1.16 (0.80–1.67) |

| Intensity 2 ** | 356/1987 | 301/1630 | 1.08 (0.89–1.29) |

| Intensity 3 ¥ | 274/1844 | 354/2632 | 1.09 (0.91–1.30) |

| Intensity 4 ¶ | 732/2673 | 551/2935 | 1.65 (1.44–1.90) |

One contact in hospital lasting 15 minutes or less with no post-discharge support

One or more contact in hospital lasting more than 15 minutes total with no post-discharge support

Any hospital contact plus post-discharge support lasting 1 month or less

Any hospital contact plus post-discharge support lasting more than 1 month

Although the effect of intensive counseling is not isolated to patients with cardiovascular disease, secondary prevention may be particularly important in this population. Smoking cessation leads to a marked reduction in mortality for patients with coronary artery disease, including patients with left ventricular dysfunction following acute myocardial infarction (43, 51–52). Unfortunately, simply complying with the current Joint Commission Standards for the provision of smoking cessation may not be sufficient to affect outcome. In an analysis of a prospective database including nearly 2500 patients with acute MI, there was no correlation between the documentation of smoking cessation counseling and successful smoking cessation at 6 months or 1 year (53). There are several potential reasons for this finding, though one may be the lack of a provision for intensive counseling in the Joint Commission quality performance measures. Recently proposed revisions of these measures address this shortcoming by adding a provision for follow-up after discharge and seeking to extend screening and intervention for smoking to all hospitalized patients.

The gap between current evidence and practice for smoking cessation counseling in hospitalized patients unfortunately persists. In one recent study, only 17% of hospitalized smokers received smoking cessation counseling (54). In a large, urban academic training hospital, only 48% of active smokers received smoking cessation counseling during an admission for a COPD exacerbation (55), despite evidence linking smoking cessation to a decreased rate of COPD exacerbation (56). Strategies including audit and feedback, the use of computers and reminders, substitution of tasks, financial interventions, and patient-mediated interventions may aid in the effective implementation of smoking cessation programs (57–58). Another strategy may be to incorporate outpatient providers and quitlines in therapy following hospital discharge (59). The incorporation of ICUs into hospital-wide smoking cessation programs should be considered. ICU nurses specifically requested they be included in training after initial exclusion from the implementation of the inpatient Veteran Administration's Tobacco Tactics program. The training of nurses in this study led to a feeling of empowerment and enthusiasm in delivering smoking cessation to patients (54).

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), now available in several different forms, is effective in increasing rates of abstinence in outpatient smokers, though the few studies performed in inpatients have not demonstrated a benefit (60–64). However, assessing the risk to benefit ratio of providing NRT to ICU patients may be particularly unique. A retrospective case-control study suggested an increase in mortality (20% vs 7%) in critically ill patients provided NRT when compared to a control group matched based on severity of illness and age (65). Unmeasured confounding may be responsible for these findings and there are no prospective or randomized studies in the ICU population. Additionally, the benefits of NRT in ICU patients may extend beyond smoking cessation. Prospective observational studies demonstrate an association between current smoking and delirium or agitation, potentially mediated by nicotine withdrawal (25, 27). Prospective randomized controlled trials examining the use of NRT in ICU patients to prevent the development of delirium and agitation and improve smoking cessation rates in ICU survivors could help ICU providers more definitively weigh the risks and benefits of NRT.

Unhealthy Alcohol Use

Unhealthy alcohol use is common in patients admitted to the ICU and is responsible for up to 40% of ICU admissions (66). The systemic effects of heavy alcohol use result in an increased risk of hospitalization(29) and predispose to multiple conditions that result in ICU admission including the acute respiratory distress syndrome (67), septic shock (68), and nosocomial infection (69–70). However, physicians often fail to recognize alcohol-related problems in patients admitted to the hospital (71). A recent proposal by the Joint Commission to include screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for unhealthy alcohol use as a quality measure in all hospitalized patients has been the source of significant controversy because of the mixed effects of BI in various hospitalized patient populations (72–74). This proposal, the detrimental effects of alcohol in multiple critical care settings, and the prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use in the ICU demand that critical care providers be familiar with the diagnosis of unhealthy alcohol use and the utility of BI in various ICU populations.

Definitions and Identification

There is a spectrum of alcohol use ranging from abstinence to alcohol dependence (Table 3). Any consumption of alcohol in excess of recommended amounts is referred to as unhealthy alcohol use (6). The severity of unhealthy alcohol use ranges from risky use to the most severe form, alcohol dependence. Alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence are often collectively referred to as alcohol use disorders (AUD). The ICD-10 and DSM-IV contain commonly used criteria for the diagnosis of alcohol abuse, and alcohol dependence (75). The DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria have high reliability, validity, and concordance for the diagnosis of alcohol dependence (76).

Table 3.

The spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use.

| Risky Alcohol Use: Consumption of alcohol in excess of recommended limits. The recommended limit for men ≤ 65 years is no more than 4 drinks per occasion or 14 drinks per week. For men > 65 years and women the recommended limit is no more than 3 drinks per occasion or 7 drinks per week. In the United States, a standard drink contains 13.7 grams of pure alcohol and is equal to one 12 ounce beer, one 5 ounce glass of wine, or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof liquor. |

| Harmful Alcohol Use: Diagnosis is based on ICD-10 criteria. Alcohol must be responsible for physical or psychological harm leading to disability or impaired relationships. The pattern of use must persist for at least 1 month or repeatedly over the preceding 12 months and the patient does not meet criteria for alcohol dependence. |

| Alcohol Abuse: Diagnosis is based on DSM-IV criteria. The criteria include failure to fulfill major role obligations, use in hazardous situations, alcohol-related legal problems, or social or interpersonal problems recurrently over a 12 month period. |

| Alcohol Dependence: The DSM-IV criteria include 3 or more of the following: tolerance, withdrawal, great deal of time spent obtaining or consuming alcohol or recovering from its effects, reducing or giving up important activities, drinking more or longer than intended, a persistent desire or unsuccessful quit attempts, and continued use despite physical or psychological consequences from alcohol. The ICD-10 criteria are similar. |

| Alcohol Use Disorder: The presence of either alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence. |

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a ten question survey that was developed by the World Health Organization and has been validated in multiple languages and healthcare settings (77). When using a score ≥ 8, the reported sensitivities range from 50–90% and specificity is approximately 80% for the identification of unhealthy alcohol use (76). In trauma patients, a cutoff of 5 for women yields a similar sensitivity and specificity as a cutoff of 8 for men (78). AUDIT surveys completed by a proxy have a high percentage of agreement in trauma patients. The level of agreement is highest in spouses, co-habitating significant others, and those with daily personal contact (79). Several laboratory tests including blood alcohol concentration, liver function tests, mean corpuscular volume, gamma-glutamyltransferase, and carbohydrate deficient transferrin may be abnormal in patients with AUDs, but lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity to be used for screening and diagnostic purposes in the ICU (80–83).

Trauma Patients

A blood alcohol level is not sufficiently sensitive nor specific to identify the one-half of hospitalized trauma patients who have an AUD (84–86). An AUD increases the rate of complications in trauma survivors including infection or the need for an operation, and increases the length of ICU stay (87–88). Whether this is true for patients acutely intoxicated with alcohol is controversial in the trauma literature (89–92). Importantly, acute alcohol intoxication and AUDs are the most important predictors of readmission for trauma, conferring a relative risk of 2.5 to 3.7 that of patients without an alcohol-related diagnosis (93–94).

The role of alcohol in readmission coupled with the high prevalence of AUDs in patients admitted to the hospital for trauma led to an interest in the role of BIs in trauma patients. In a randomized trial of BI that included ICU patients, trauma patients who received an intervention consumed nearly 15 fewer alcoholic beverages per week than patients in the control group 12 months after discharge. This was coupled with a 47% reduction in injuries. The BI was performed by a psychologist on or near the day of discharge and incorporated the techniques of MI. The effect was mostly confined to patients with risky alcohol use (15). Brief interventions also halve the rate of arrests for driving under the influence following an admission for trauma related to a motor vehicle crash (95). The implementation of screening and BI in trauma centers is feasible (96). Furthermore, screening and BI in trauma centers is cost-effective and leads to an average savings of $89 for each patient screened (97). Based on the high prevalence of AUDs in hospitalized trauma patients and the efficacy, feasibility, and cost-effectiveness of BI, the American College of Surgeons now requires screening and BI services for unhealthy alcohol use for Level I Trauma designation (98).

Medical Patients

There is a high prevalence of patients with alcohol-related problems in the medical ICU and heavy alcohol consumption increases the risk of morbidity and mortality (68). Brief interventions decrease alcohol consumption and healthcare utilization in patients with risky alcohol use when delivered opportunistically to outpatients (99). It would, therefore, seem logical that the period of abstinence offered by a hospitalization for a medical illness may provide a “teachable moment.” Although no studies have specifically assessed the efficacy of BI in medical ICU patients, numerous studies of BI in medical inpatients fail to demonstrate a reduction in alcohol consumption following hospital discharge (100). In a recent large randomized trial in medical inpatients, BI did not increase the proportion of patients receiving alcohol assistance when compared to usual care (44% vs 49%) (101). A potential reason for the lack of efficacy in medical inpatients may be that the spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use in medical inpatients is skewed toward patients with alcohol dependence, a group that may not respond to BI (102). Regardless, the current evidence would not support the systematic implementation of BI for medical inpatients.

Conclusion

Smoking and unhealthy alcohol use are public health problems that commonly result in critical illness. Reliable screening systems can lead to identification of these treatable conditions in patients admitted to the ICU. Addressing smoking through the delivery of intensive interventions and, when appropriate, the use of pharmacotherapy can lead to a significant improvement in smoking cessation rates. Appropriately delivered brief interventions can have a dramatic effect on alcohol consumption in trauma patients and reduce trauma recidivism, but studies do not conclusively show an effect when delivered to medical inpatients. If performance measures are to be evidence-based, the current level of evidence would not completely support the inclusion of medical ICU patients in screening and BI efforts for unhealthy alcohol use (103). Future studies should address the efficacy of BI in medical ICU patients and the optimal timing of these interventions. Potential moderators and mediators of the efficacy of BI, such as the type of healthcare provider providing the intervention, will also be important. The effective implementation of interventions deemed to be efficacious will also need to overcome barriers to implementation – some unique to critical care and others proven to be surmountable in other healthcare settings.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(18):2207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses - United States, 2000–2004. MMWR. 2008;57(45):1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(5):w822–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harwood H. [Accessed November 11, 2010];Updating Estimates of the Economic Costs of Alcohol Abuse in the United States: Estimates, Update Methods, and Data. Available online at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/economic-2000/.

- 6.Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):596–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96(12):1725–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitka M. “Teachable moments” provide a means for physicians to lower alcohol abuse. JAMA. 1998;279(22):1767–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.22.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing with Problem Drinkers. Behavioral Psychotherapy. 1983;11:147–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller WR, Baca LM. Two-year Follow-up of Bibliotherapy and Therapist-directed Controlled Drinking Training for Problem Drinkers. Behavior Therapy. 1983;14:441–48. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller WR, Benefield RG, Tonigan JS. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: a controlled comparison of two therapist styles. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(3):455–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feeney GF, McPherson A, Connor JP, McAlister A, Young MR, Garrahy P. Randomized controlled trial of two cigarette quit programmes in coronary care patients after acute myocardial infarction. Intern Med J. 2001;31(8):470–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2001.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sivarajan Froelicher ES, Miller NH, Christopherson DJ, Martin K, Parker KM, Amonetti M, et al. High rates of sustained smoking cessation in women hospitalized with cardiovascular disease: the Women's Initiative for Nonsmoking (WINS) Circulation. 2004;109(5):587–93. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115310.36419.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigotti NA, McKool KM, Shiffman S. Predictors of smoking cessation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Results of a randomized trial with 5-year follow-up. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(4):287–93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-4-199402150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, Daranciang E, Dunn CW, et al. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Ann Surg. 1999;230(4):473–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. discussion 80–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham DM, Maio RF, Blow FC, Hill EM. Emergency physician attitudes concerning intervention for alcohol abuse/dependence delivered in the emergency department: a brief report. J Addict Dis. 2000;19(1):45–53. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lock CA, Kaner E, Lamont S, Bond S. A qualitative study of nurses' attitudes and practices regarding brief alcohol intervention in primary health care. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(4):333–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aalto M, Pekuri P, Seppa K. Primary health care professionals' activity in intervening in patients' alcohol drinking: a patient perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams A, Ockene JK, Wheller EV, Hurley TG. Alcohol counseling: physicians will do it. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(10):692–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. [Accessed August 27, 2010];Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Smoking and Tobacco Use Fast Facts. Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm.

- 22.Vital Signs: Current Cigarette smoking Among Adults Aged > 18 years - United States 2009. MMWR. 2010;59(35):23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, Curry SJ, et al. [Accessed Septemer 2, 2010];Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Available online at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/treating_tobacco_use.pdf.

- 24. [Accessed September 22, 2010];U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: 2004 Surgeon General's Report - The Health Consequences of Smoking. Accessed online at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2004/index.htm.

- 25.Van Rompaey B, Elseviers MM, Schuurmans MJ, Shortridge-Baggett LM, Truijen S, Bossaert L. Risk factors for delirium in intensive care patients: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2009;13(3):R77. doi: 10.1186/cc7892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucidarme O, Seguin A, Daubin C, Ramakers M, Terzi N, Beck P, et al. Nicotine withdrawal and agitation in ventilated critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):R58. doi: 10.1186/cc8954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moller AM, Pedersen T, Villebro N, Schnaberich A, Haas M, Tonnesen R. A study of the impact of long-term tobacco smoking on postoperative intensive care admission. Anaesthesia. 2003;58(1):55–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.02788_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hvidtfeldt UA, Rasmussen S, Gronbaek M, Becker U, Tolstrup JS. Influence of smoking and alcohol consumption on admissions and duration of hospitalization. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(4):376–82. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haapanen-Niemi N, Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Pasanen M, Oja P. The impact of smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity on use of hospital services. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(5):691–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.691. PMCID: 1508744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkins K, Shields M, Rotermann M. Smokers' use of acute care hospitals--a prospective study. Health Rep. 2009;20(4):75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. [Accessed September 23, 2010];Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Health Interview Survey 2010. Accessed online at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

- 33.Hatsukami DK, Stead LF, Gupta PC. Tobacco addiction. Lancet. 2008;371(9629):2027–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60871-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh SJ, Ware LB, Eisner MD, Yu L, Jacob P, 3rd, Havel C, et al. Biomarkers increase detection of active smoking and secondhand smoke exposure in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(1):40–5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fa4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shourie S, Conigrave KM, Proude EM, Haber PS. Detection of and intervention for excessive alcohol and tobacco use among adult hospital in-patients. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(2):127–33. doi: 10.1080/09595230601145175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benowitz NL, Schultz KE, Haller CA, Wu AH, Dains KM, Jacob P., 3rd Prevalence of smoking assessed biochemically in an urban public hospital: a rationale for routine cotinine screening. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(7):885–91. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp215. PMCID: 2765360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lancaster T, Stead L. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD000165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hajek P, Taylor TZ, Mills P. Brief intervention during hospital admission to help patients to give up smoking after myocardial infarction and bypass surgery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;324(7329):87–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reid RD, Quinlan B, Riley DL, Pipe AL. Smoking cessation: lessons learned from clinical trial evidence. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22(4):280–5. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328236740a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vidrine JI, Cofta-Woerpel L, Daza P, Wright KL, Wetter DW. Smoking cessation 2: behavioral treatments. Behav Med. 2006;32(3):99–109. doi: 10.3200/BMED.32.3.99-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith PM, Burgess E. Smoking cessation initiated during hospital stay for patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2009;180(13):1297–303. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Superko HR, Dennis CA, Thomas RJ, Lew HT, et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(9):721–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller NH, Smith PM, DeBusk RF, Sobel DS, Taylor CB. Smoking cessation in hospitalized patients. Results of a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(4):409–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ockene J, Kristeller JL, Goldberg R, Ockene I, Merriam P, Barrett S, et al. Smoking cessation and severity of disease: the Coronary Artery Smoking Intervention Study. Health Psychol. 1992;11(2):119–26. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dornelas EA, Sampson RA, Gray JF, Waters D, Thompson PD. A randomized controlled trial of smoking cessation counseling after myocardial infarction. Prev Med. 2000;30(4):261–8. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hennrikus DJ, Lando HA, McCarty MC, Klevan D, Holtan N, Huebsch JA, et al. The TEAM project: the effectiveness of smoking cessation intervention with hospital patients. Prev Med. 2005;40(3):249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagle AL, Hensley MJ, Schofield MJ, Koschel AJ. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a nurse-provided intervention for hospitalised smokers. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29(3):285–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):1950–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.18.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohiuddin SM, Mooss AN, Hunter CB, Grollmes TL, Cloutier DA, Hilleman DE. Intensive smoking cessation intervention reduces mortality in high-risk smokers with cardiovascular disease. Chest. 2007;131(2):446–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Critchley JA, Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;290(1):86–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shah AM, Pfeffer MA, Hartley LH, Moye LA, Gersh BJ, Rutherford JD, et al. Risk of all-cause mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction, and heart failure hospitalization associated with smoking status following myocardial infarction with left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(7):911–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reeves GR, Wang TY, Reid KJ, Alexander KP, Decker C, Ahmad H, et al. Dissociation between hospital performance of the smoking cessation counseling quality metric and cessation outcomes after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2111–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duffy SA, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Ewing LA, Smith PM. Implementation of the Tobacco Tactics program in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 1):3–10. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yip NH, Yuen G, Lazar EJ, Regan BK, Brinson MD, Taylor B, et al. Analysis of hospitalizations for COPD exacerbation: opportunities for improving care. COPD. 2010;7(2):85–92. doi: 10.3109/15412551003631683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Au DH, Bryson CL, Chien JW, Sun H, Udris EM, Evans LE, et al. The effects of smoking cessation on the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):457–63. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0907-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, Sakrouge R, McElduff P, Walsh RA, et al. Increasing smoking cessation care provision in hospitals: a meta-analysis of intervention effect. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(6):650–62. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Winickoff JP, Hillis VJ, Palfrey JS, Perrin JM, Rigotti NA. A smoking cessation intervention for parents of children who are hospitalized for respiratory illness: the stop tobacco outreach program. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):140–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campbell IA, Prescott RJ, Tjeder-Burton SM. Smoking cessation in hospital patients given repeated advice plus nicotine or placebo chewing gum. Respir Med. 1991;85(2):155–7. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campbell IA, Prescott RJ, Tjeder-Burton SM. Transdermal nicotine plus support in patients attending hospital with smoking-related diseases: a placebo-controlled study. Respir Med. 1996;90(1):47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(96)90244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewis SF, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Anderson JE, Baker TB. Transdermal nicotine replacement for hospitalized patients: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 1998;27(2):296–303. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Molyneux A, Lewis S, Leivers U, Anderton A, Antoniak M, Brackenridge A, et al. Clinical trial comparing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) plus brief counselling, brief counselling alone, and minimal intervention on smoking cessation in hospital inpatients. Thorax. 2003;58(6):484–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.6.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee AH, Afessa B. The association of nicotine replacement therapy with mortality in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(6):1517–21. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266537.86437.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marik P, Mohedin B. Alcohol-related admissions to an inner city hospital intensive care unit. Alcohol Alcohol. 1996;31(4):393–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moss M, Bucher B, Moore FA, Moore EE, Parsons PE. The role of chronic alcohol abuse in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults. JAMA. 1996;275(1):50–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Brien JM, Jr., Lu B, Ali NA, Martin GS, Aberegg SK, Marsh CB, et al. Alcohol dependence is independently associated with sepsis, septic shock, and hospital mortality among adult intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):345–50. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254340.91644.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gacouin A, Legay F, Camus C, Volatron AC, Barbarot N, Donnio PY, et al. At-risk drinkers are at higher risk to acquire a bacterial infection during an intensive care unit stay than abstinent or moderate drinkers. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1735–41. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174dd75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Delgado-Rodriguez M, Mariscal-Ortiz M, Gomez-Ortega A, Martinez-Gallego G, Palma-Perez S, Sillero-Arenas M, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of nosocomial infection in general surgery. Br J Surg. 2003;90(10):1287–93. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moore RD, Bone LR, Geller G, Mamon JA, Stokes EJ, Levine DM. Prevalence, detection, and treatment of alcoholism in hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1989;261(3):403–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Field CA, Baird J, Saitz R, Caetano R, Monti PM. The mixed evidence for brief intervention in emergency departments, trauma care centers, and inpatient hospital settings: what should we do? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(12):2004–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saitz R. Candidate performance measures for screening for, assessing, and treating unhealthy substance use in hospitals: advocacy or evidence-based practice? Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(1):40–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-1-201007060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saitz R. Candidate Measures for Screening for, Assessing, and Treating Unhealthy Substance Use in Hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(1):72–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hasin D. Classification of alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(1):5–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492–501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. [Accessed January 27, 2011];World Health Organization. 2001 Available online at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/who_msd_msb_01.6a.pdf.

- 78.Neumann T, Neuner B, Gentilello LM, Weiss-Gerlach E, Mentz H, Rettig JS, et al. Gender differences in the performance of a computerized version of the alcohol use disorders identification test in subcritically injured patients who are admitted to the emergency department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(11):1693–701. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145696.58084.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Donovan DM, Dunn CW, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Ries RR, Gentilello LM. Comparison of trauma center patient self-reports and proxy reports on the Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) J Trauma. 2004;56(4):873–82. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000086650.27490.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Neumann T, Spies C. Use of biomarkers for alcohol use disorders in clinical practice. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 2):81–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Conigrave KM, Davies P, Haber P, Whitfield JB. Traditional markers of excessive alcohol use. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 2):31–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martin MJ, Heymann C, Neumann T, Schmidt L, Soost F, Mazurek B, et al. Preoperative evaluation of chronic alcoholics assessed for surgery of the upper digestive tract. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(6):836–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moss M, Burnham EL. Alcohol abuse in the critically ill patient. Lancet. 2006;368(9554):2231–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Gurney JG, Seguin D, Fligner CL, Ries R, et al. The magnitude of acute and chronic alcohol abuse in trauma patients. Arch Surg. 1993;128(8):907–12. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420200081015. discussion 12–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Soderstrom CA, Dischinger PC, Smith GS, McDuff DR, Hebel JR, Gorelick DA. Psychoactive substance dependence among trauma center patients. JAMA. 1992;267(20):2756–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gentilello LM, Villaveces A, Ries RR, Nason KS, Daranciang E, Donovan DM, et al. Detection of acute alcohol intoxication and chronic alcohol dependence by trauma center staff. J Trauma. 1999;47(6):1131–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199912000-00027. discussion 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Gurney JG, Fligner C, Ries R, Mueller BA, et al. The effect of acute alcohol intoxication and chronic alcohol abuse on outcome from trauma. JAMA. 1993;270(1):51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Spies CD, Kissner M, Neumann T, Blum S, Voigt C, Funk T, et al. Elevated carbohydrate-deficient transferrin predicts prolonged intensive care unit stay in traumatized men. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33(6):661–9. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/33.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Swearingen A, Ghaemmaghami V, Loftus T, Swearingen CJ, Salisbury H, Gerkin RD, et al. Extreme blood alcohol level is associated with increased resource use in trauma patients. Am Surg. 2010;76(1):20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rootman DB, Mustard R, Kalia V, Ahmed N. Increased incidence of complications in trauma patients cointoxicated with alcohol and other drugs. J Trauma. 2007;62(3):755–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318031aa7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeckey C, Dannecker S, Hildebrand F, Mommsen P, Scherer R, Probst C, et al. Alcohol and multiple trauma-is there an influence on the outcome? Alcohol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Klasen J, Junger A, Hartmann B, Quinzio L, Benson M, Rohrig R, et al. Excessive alcohol consumption and perioperative outcome. Surgery. 2004;136(5):988–93. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fabbri A, Marchesini G, Dente M, Iervese T, Spada M, Vandelli A. A positive blood alcohol concentration is the main predictor of recurrent motor vehicle crash. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(2):161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Jurkovich GJ, Gurney JG, Soderberg R. The effects of alcohol abuse on readmission for trauma. JAMA. 1993;270(16):1962–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schermer CR, Moyers TB, Miller WR, Bloomfield LA. Trauma center brief interventions for alcohol disorders decrease subsequent driving under the influence arrests. J Trauma. 2006;60(1):29–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199420.12322.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schermer CR. Feasibility of alcohol screening and brief intervention. J Trauma. 2005;59(3 Suppl):S119–23. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000174679.12567.7c. discussion S24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gentilello LM, Ebel BE, Wickizer TM, Salkever DS, Rivara FP. Alcohol interventions for trauma patients treated in emergency departments and hospitals: a cost benefit analysis. Ann Surg. 2005;241(4):541–50. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157133.80396.1c. PMCID: 1357055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gentilello LM. Alcohol and injury: American College of Surgeons Committee on trauma requirements for trauma center intervention. J Trauma. 2007;62(6 Suppl):S44–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180654678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers. A randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1039–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Emmen MJ, Schippers GM, Bleijenberg G, Wollersheim H. Effectiveness of opportunistic brief interventions for problem drinking in a general hospital setting: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;328(7435):318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37956.562130.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, Horton NJ, Freedner N, Dukes K, et al. Brief intervention for medical inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(3):167–76. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Saitz R, Freedner N, Palfai TP, Horton NJ, Samet JH. The severity of unhealthy alcohol use in hospitalized medical patients. The spectrum is narrow. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(4):381–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00405.x. PMCID: 1484710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chassin MR, Loeb JM, Schmaltz SP, Wachter RM. Accountability measures--using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):683–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1002320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]