Abstract

Background:

Tobacco use is a major cause of avoidable mortality. Postgraduate doctors in training are an important group of physicians likely to influence patients’ tobacco use/cessation.

Objective:

To assess preparedness for tobacco control among clinical postgraduate residents of a medical college in southern India.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was undertaken among all clinical postgraduate residents enrolled in St. John's Medical College, Bangalore, to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding tobacco cessation in their patients. A self-administered, anonymous questionnaire was used. Simple descriptive analysis was undertaken.

Results:

The overall response rate was 66% (76/116). Mean (S.D.) knowledge score on tobacco use prevalence and disease burden was 6.2 (2.0) out of 10. About 25% of them were not aware of nicotine replacement therapy as a treatment option for tobacco cessation. Nearly two thirds of them expected their patients to ask for assistance with quitting and nearly half were sceptical about patients’ ability to quit. While 80% of them enquired routinely about tobacco use in their patients, only 50% offered advice on quitting and less than a third assessed readiness to quit or offered assistance with quitting in their patients.

Conclusion:

Our study revealed suboptimal levels of knowledge and tobacco cessation practice among postgraduate residents. Attitudes toward tobacco cessation by their patients was however generally positive and there was substantial interest in further training in tobacco control. Reorienting postgraduate medical education to include tobacco control interventions would enable future physicians to be better equipped to deal with nicotine addiction.

Keywords: India, postgraduate medical education, tobacco cessation

Introduction

Tobacco use is now understood to impose a large and growing public health burden worldwide. Globally, tobacco use is estimated to lead to 1 in 5 male deaths and 1 in 20 female deaths among those over age 30 thus causing over 5 million deaths annually.(1) In India, tobacco-attributable mortality is estimated to increase from 1% of total mortality in 1990 to 13% by 2020.(2) There is however widespread under-appreciation of the health effects of tobacco use. Among available interventions to reduce tobacco-associated mortality, it is now estimated that tobacco cessation is more likely to avert millions of deaths over the next few decades than the prevention of tobacco use initiation. Research over the last two decades has identified behavioural counselling and pharmaceuticals as two cost-effective tobacco cessation strategies for use in clinical practice.(1,3,4) Tobacco cessation is thus an increasingly relevant intervention in clinical settings in developing countries like India. Graduate medical residents are an appropriate group among health professionals for assessing preparedness for tobacco control. This communication reports on a survey conducted among postgraduate residents of a medical college in southern India with the following objectives: (i) to evaluate knowledge regarding tobacco-attributable disease burden; (ii) to assess attitudes relating to tobacco use among patients and (iii) to study tobacco cessation/control practices followed by them routinely in their clinical work.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Needs assessment survey using a cross-sectional study design.

Study population and setting

All postgraduate residents enrolled in three types of clinical degree programs (diploma, masters and specialty courses) at St. John's Medical College Hospital, a 1200-bed hospital located in Bangalore, were the study participants. An explanatory note detailing the study objectives was distributed to them in a classroom/individual setting and written consent for participation was obtained. Then the anonymized, self-administered questionnaires were distributed to them and collected after completion (usually about 30-40 min). The study was cleared by the St. John's institutional ethics review board and conducted during January-May 2007.

Study instrument

A two-page, 24-item questionnaire was designed to obtain information on the three domains (cognitive, attitude, and practice) relating to tobacco control. Cognitive (knowledge) and attitude domains were assessed according to Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives–at the knowledge level for the cognitive domain and at the organization level for the attitude domain.(5) For the cognitive domain, knowledge on tobacco-related disease burden was studied; for the attitude domain, residents’ attitudes regarding tobacco use and quitting by their patients was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. To assess the quality of tobacco cessation clinical practice, residents’ adherence to tobacco control guidelines suggested by the U.S. Public Health Services(3,6) based on Prochaska's Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change was estimated;(7,8) for this we used a 3-point scale with narrative description (“always or often,” “sometimes,” and “never/rarely”). In addition, they were also asked to rate subjectively, using a 3-point descriptive scale (low, average, and high), the adequacy of their prior training, proficiency in tobacco control management, and interest in further training for tobacco control. Question items were developed based on literature review(9,10) and pilot-tested for item clarity.

Analysis

Data was entered and analyzed using Stata (version 8.0). Frequency distributions were calculated for outcomes of interest. Significance was taken at P<0.05.

Results

Out of a total of 116 clinical residents, 110 (95%) were contacted and 76 (66%) participated in the survey. There were 18 diploma students, 50 master's students, and 8 specialty students; 32% were females. The mean (standard deviation) age of respondents was 28 years (2.9 yrs). The mean number of patients seen by the resident trainees was reported to be 133 in the out-patient clinic and 109 in the in-patient setting during the preceding month.

Knowledge

The overall mean knowledge score was 6.2 (95% C.I.= 6.0, 6.5) out of a total of 10; this did not vary significantly by age (P=0.76), gender (P=0.41), type of degree (P=0.26), or completed years of graduate training (P=0.07). Over two-thirds were not aware of the prevalence of tobacco use in the country (with over half of them reporting that it was less than 20%). 55% of them perceived “ultra-light” or “light” cigarettes to be less harmful than regular cigarettes. On diseases related to tobacco use, 55% of them answered that there was no link whatsoever between smoking and tuberculosis. Although most of them knew about the association between smoking and cardiovascular disease, about 20% of them thought that smoking was not linked to stroke and 15% replied that smoking had no association with heart attack. Almost all of them answered correctly on questions relating to association between smoking and cancer, and smoking and reproductive health. Regarding tobacco cessation, about 25% of them were not aware of nicotine replacement therapy as a treatment option for tobacco cessation.

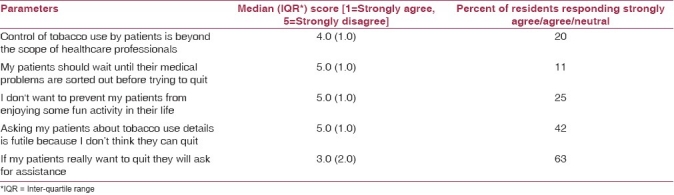

Attitude

Median (and inter-quartile range) attitude scores and proportions giving negative/ambivalent (strongly agree/agree/neutral) responses to attitude questions are shown in Table 1. Few residents (≤20%) held negative/ambivalent attitudes regarding role of healthcare professionals in tobacco cessation and addressing patients’ tobacco use problem simultaneously with physical medical problems. However, about 1 in 4 residents perceived tobacco use in patients as a permissible “fun activity” in life not to be intervened upon. 42% of them had serious reservations about patients’ ability to quit tobacco use and nearly two thirds of them would wait for their patients to ask for assistance with quitting.

Table 1.

Postgraduate residents’ attitudes on tobacco use and quitting by their patients

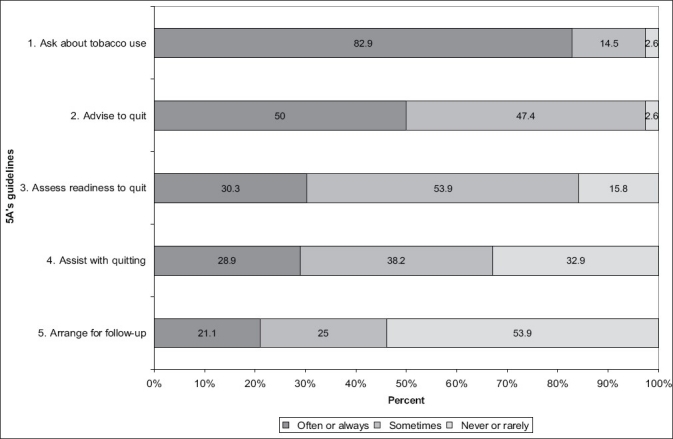

Practice

Residents reported frequency of practice of 5A's for tobacco cessation is depicted in Figure 1. While over 80% routinely enquired about their patients’ tobacco use, only 50% offered advice regarding quitting. Less than a third of them assessed readiness to quit or initiated assistance with quitting and only about one in five arranged for continued follow-up.

Figure 1.

Postgraduate residents’ reported frequency of use of the 5A Tobacco cessation guidelines

Training adequacy, current proficiency, and interest in training

74% of residents responded that their training regarding tobacco control was inadequate (low/average) and 69% of them rated themselves as currently of low/average proficiency in routine clinical tobacco cessation practice. 95% of residents reported average/high interest in further training on tobacco control.

Discussion

Our study has revealed suboptimal levels of residents’ knowledge of tobacco use and its health effects. Over half of them believed in the tobacco-industry propagated myth of “ultra-light/light” cigarettes being a safer alternative to “regular” cigarettes. While a minority was unaware of the association between smoking and cardiovascular diseases (myocardial infarction and stroke), a substantial proportion of them also failed to identify the link between smoking and tuberculosis.

Overall attitudes to tobacco usage by their patients were healthy, revealing few barriers to improved participation of healthcare professionals in tobacco control. A sizeable fraction of them however were permissive of tobacco use in their patients as an acceptable lifestyle not necessitating any intervention. A majority of them also would apparently wait for their patients to ask for assistance with quitting. This reveals an under-appreciation of the addictive potential of nicotine on the part of residents given that tobacco use is less often associated with social, medical, economic, or behavioral perturbations in the early phase of nicotine dependence unlike other addictions like alcohol, drugs, or gambling.

While most of the residents routinely asked their patients about substance abuse as part of their clinical enquiry, majority did not engage in the other components of the 5A's (advice, assess, assist, or arrange follow-up). Many had reported low level of academic input on tobacco cessation during their professional training; more positively, a majority had evinced keen interest in acquiring further training on tobacco control.

Tobacco research on postgraduate residents is limited in India.(11) Numerous studies are however available from elsewhere on residents in internal medicine, psychiatry, obstetrics, pediatrics, preventive medicine, and family medicine.(10,12–19) Most studies have identified insufficient formal training and some negative attitudes as key barriers to enhanced participation of healthcare professionals in tobacco control. In routine clinical practice worldwide, residents appear to ask about and offer advice on tobacco use but involve themselves less often in assessing, assisting or arranging follow-up for tobacco cessation.(10,14,19)

Tobacco control interventions in clinical settings could take the form of “in-depth counseling” where resources permit or could be “opportunistic counseling” (brief interventions lasting <10 min) in busy settings.(4,20) Residents’ training in tobacco control has been shown to be productive in many ways: it has increased knowledge, reduced skepticism, and resulted in higher level of adherence to current practice guidelines (5As). An increased likelihood of quit attempts, reduction or abstinence from cigarette use by their patients has also been demonstrated. Several authors have suggested multiple approaches to enhancing training for tobacco control–setting of educational standards, development of faculty expertise, creation of education material, and targeting of attainment of competencies in all three domains (that is, improvement in knowledge, attitudes, and routine clinical practice).(18,21–23) Several teaching-learning aids (didactic lectures, CD-ROMs, role-plays, and standardized patients at various stages of change) have been suggested for those specifically interested in preparing training material.(23,24) Online training material is also available from some sources.(25,26)

It has been documented that residents report low professional satisfaction in treating addictions in their patients owing to poor attitudes.(27) Hence, in addition to improving knowledge, improving attitudes appears to be a key in the effective use of knowledge in routine clinical practice.

This is probably the first comprehensive study among postgraduate clinical residents in India on their knowledge, attitude, and practice relating to tobacco control in their patients. There are however some key limitations. It is based on residents in a single institution, participation was average and representativeness of the sample was not known. In addition, all findings were based on self-reporting and social desirability bias could not be assessed.(28) Hence, these findings may need to be corroborated from other centres in India. Further, we did not assess tobacco use by the postgraduates themselves; if their tobacco use status was known, stratified analysis would have helped gain a deeper understanding of the knowledge, attitude, and practices in the two subgroups. We however know from another recent study that current tobacco use was reported by <1% of third-year undergraduate medical students in Bangalore city.(29)

In conclusion, our study revealed low levels of knowledge and tobacco cessation intervention in clinical practice by postgraduate residents. Suboptimal academic input appears to be a crucial factor. Attitude toward tobacco cessation in their patients was generally upbeat among clinical residents and there was heightened interest in further training in tobacco control. Reorienting postgraduate medical training(30) to include tobacco control interventions would enable future physicians to be better equipped to deal with a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the 21st century.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Prem Pais, MD, Professor and Dean, St. John's Medical College, for administrative support for the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The study received financial support from St. John's Medical College Research Society

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, Moore J, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, Peck R, et al. Tobacco Addiction. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 869–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobacco or health: A global status report. Geneva: WHO; 1997. World Health Organization (WHO) [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Public Health Service (USPHS). A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: A US Public Health Service report. The Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline Panel, Staff and Consortium Representatives. JAMA. 2000;283:3244–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornuz J. Smoking cessation interventions in clinical practice. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. [Last accessed on 2006 Aug 2]. Available from: http://www.fctel.uncc.edu/pedagogy/basicscoursedevelop/Bloom.html .

- 6.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1996. Cessation. Clinical Practice Guideline 18. AHCPR 96-0692. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Self change processes, self efficacy and decisional balance across five stages of smoking cessation. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1984;156:131–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kviz FJ, Clark MA, Prohaska TR, Slezak JA, Crittenden KS, Freels S, et al. Attitudes and practices for smoking cessation counseling by provider type and patient age. Prev Med. 1995;24:201–12. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prochaska JJ, Fromont SC, Hall SM. How prepared are psychiatry residents for treating nicotine dependence? Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29:256–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.29.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkar D, Dhand R, Malhotra A, Malhotra S, Sharma BK. Perceptions and attitude towards tobacco smoking among doctors in Chandigarh. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 1990;32:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strecher VJ, O’Malley MS, Villagra VG, Campbell EE, Gonzalez JJ, Irons TG, et al. Can residents be trained to counsel patients about quitting smoking.Results from a randomized trial? J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02599383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potter B, Fleming MF. Obstetrics and gynecology resident education in tobacco, alcohol, and drug use disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003;30:583–99, vii. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(03)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hymowitz N, Schwab J, Haddock CK, Burd KM, Pyle S. The Pediatric Residency Training on Tobacco Project: Baseline findings from the resident tobacco survey and observed structured clinical examinations. Prev Med. 2004;39:507–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein JD, Portilla M, Goldstein A, Leininger L. Training pediatric residents to prevent tobacco use. Pediatrics. 1995;96:326–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosower E, Ernst A, Taub B, Berman N, Andrews J, Seidel J. Tobacco prevention education in a pediatric residency program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:430–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170160084012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins RL, D’Angelo S, Stearns SD, Campbell LR. Training pediatric residents to provide smoking cessation counseling to parents. Scientific World Journal. 2005;5:410–9. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2005.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrams Weintraub T, Saitz R, Samet JH. Education of preventive medicine residents: Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug abuse. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:101–5. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlieb NH, Guo JL, Blozis SA, Huang PP. Individual and contextual factors related to family practice residents’ assessment and counseling for tobacco cessation. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:343–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kristeller JL, Ockene JK. Tobacco curriculum for medical students, residents and practicing physicians. Indiana Med. 1996;89:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming M, Barry K, Davis A, Kropp S, Kahn R, Rivo M. Medical education about substance abuse: changes in curriculum and faculty between 1976 and 1992. Acad Med. 1994;69:362–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humair JP, Cornuz J. A new curriculum using active learning methods and standardized patients to train residents in smoking cessation. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:1023–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.20732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornuz J, Humair JP, Seematter L, Stoianov R, van Melle G, Stalder H, et al. Efficacy of resident training in smoking cessation: a randomized, controlled trial of a program based on application of behavioral theory and practice with standardized patients. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:429–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-6-200203190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Institute for Global Tobacco Control. [Last accessed on 2007 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.globaltobaccocontrol.org/

- 26.Ontario Tobacco Research Unit (OTRU). Tobacco and Public Health: From theory to practice. [Last accessed on 2007 Feb 30]. Available from: http://www.tobaccocourse.otru.org/

- 27.Saitz R, Friedmann PD, Sullivan LM, Winter MR, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Moskowitz MA, et al. Professional satisfaction experienced when caring for substance-abusing patients: faculty and resident physician perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:373–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulhus DL, Reid DB. Enhancement and denial in socially desirable responding. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:307–17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mony P, John P, Jayakumar S. Tobacco use habits and beliefs among undergraduate medical and nursing students of two cities in southern India. Natl Med J India. 2010;23:340–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benegal V, Bajpai A, Basu D, Bohra N, Chatterji S, Galgali RB, et al. Proposal to the Indian Psychiatric Society for adopting a specialty section on addiction medicine (alcohol and other substance abuse) Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:277–82. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]