Abstract

Hypocalcemia is a less known but treatable cause for dilated cardiomyopathy, leading to severe heart failure in children. Cardiogenic shock related to hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy is a rare event. We describe 5 infants presenting with cardiogenic shock over 3 years, who were found to have severe hypocalcemia as a sole cause of myocardial dysfunction. The patients responded to calcium and vitamin D supplementation promptly and left ventricular systolic function normalized within months of treatment. In any case of cardiogenic shock, hypocalcemia should be included in the differential diagnosis and must be investigated.

Keywords: Calcium supplementation, cardiogenic shock, dilated cardiomyopathy, hypocalcaemia

INTRODUCTION

Hypocalcemia reduces myocardial contractility,[1] but the incidence of congestive heart failure (CHF) due to hypocalcemia is infrequent in clinical practice. Several cases of hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy have been reported.[2–6] In these cases, correction of hypocalcemia was associated with resolution of CHF and in most patients the left ventricular (LV) geometry and systolic function recovered completely.[7,8] However, cardiogenic shock related to hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy is a rarely described event. We herein report our experience with 5 infants who had presented to the emergency in cardiogenic shock and the cause was attributed to hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy. All but 1 patient recovered completely after correction of hypocalcemia.

METHODS

We reviewed the records of 26 infants who presented with dilated cardiomyopathy associated with hypocalcemia between July 2007 and August 2010. A subset of these patients has been reported from our institution.[7] Five infants who presented in cardiogenic shock were included in this retrospective analysis. Cardiogenic shock was defined as hypotension with clinical signs of poor tissue perfusion, which include oliguria, cyanosis, cool extremities, and altered mentation. These signs persisted after attempts have been made to correct hypovolemia, arrhythmia, hypoxia, and acidosis.

Demographic data, including age, gender, and weight, were recorded and the details of presentation, including symptomatology, clinical signs, feeding habits, maternal supplementation, and history of undiagnosed sudden death in siblings, were recorded. The patients were investigated according to the cardiomyopathy protocol of our institute, which included electrocardiogram, chest X-ray frontal view, echocardiography, blood gas analysis, Sepsis screen, renal and liver function test, serum electrolytes, including calcium, ionized calcium, inorganic phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase. Serum parathyroid hormone level (chemiluminescent immunoassay), serum vitamin D (25-hydroxy) level (chromatography radioreceptor H3 assay), and serum metabolic profile for inborn errors of metabolism (tandem mass spectrometry) were also analyzed in all infants.

RESULTS

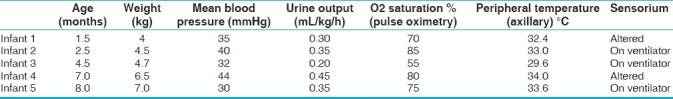

The median (range) of age at presentation was 4 months (6 weeks to 8 months) with median weight of 4.7 kg (4–7 kg) [Table 1]. All infants were referred from local hospital and presented to emergency department with cardiogenic shock requiring ionotropic support, while 3 were on ventilator. One of these infants was diagnosed as rickets and was on oral calcium supplementation. The child had recurrent convulsions following febrile illness along with hypocalcemia at home and immediately shifted to a nearby hospital. One infant had presented with pulseless ventricular tachycardia for which DC cardioversion was done along with stabilization with ventilatory and ionotropic support. Another child also had generalized convulsion at presentation. Feeding history revealed that 2 infants were on combination of breastfeed and formula feed, 2 were exclusively on breastfeed and 1 was on cow's milk. Except 1 infant, none had received vitamin D or calcium supplementation postnatally. History of maternal supplementation was present in 2 infants. There was no history of undiagnosed sudden death in siblings in any of the family.

Table 1.

Clinical profile at presentation

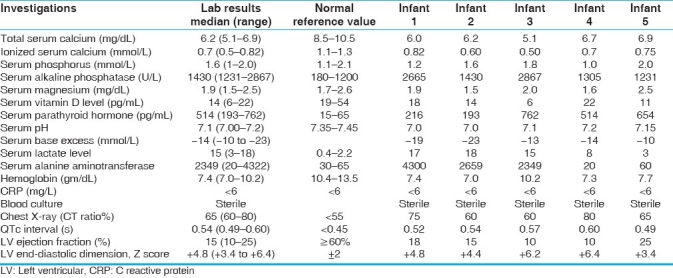

The investigations at presentations are shown in Table 2. Chest radiograph revealed gross cardiomegaly in all cases. Twelve lead electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia, normal frontal QRS axis for age, and prolonged corrected QT interval. Two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography revealed severely decreased LV systolic function with median ejection fraction of 15% (range, 10%-25%), reduced fractional shortening (FS) and dilated left ventricle with median LV diastolic dimension Z score +4.8 (range +3.4 to +6.4). Coronaries had normal origin and course and no structural heart defect was detected. All infants had severe metabolic acidosis with median PH of 7.10, base excess of -14 mmol/L, and lactate of 15 mmol/L. All infants had severe hypocalcemia at the time of presentation (range, 5.1–6.9 mg/dL) [Table 2]. Serum magnesium level was low in 2 cases and normal in rest of the cases. Serum parathyroid hormone level was elevated (secondary hyperparathyroidism) in all cases. Serum vitamin D (25 hydroxy Vit D) levels were low in all except a patient who had low normal level. Screening for inborn errors of metabolism (tandem mass spectrometry) was normal in all the infants. All cases were anemic with hemoglobin ranged between 7 and 10.2 g/dL and received packed cell transfusion. Sepsis screen was negative and blood cultures were sterile in all cases. Hepatic enzymes, including aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, were severely deranged in 3 cases, which normalized over 2–5 days period. Maternal serum calcium, alkaline phosphatase, and serum phosphorus levels were checked in all and were within normal limits.

Table 2.

Investigations at presentation

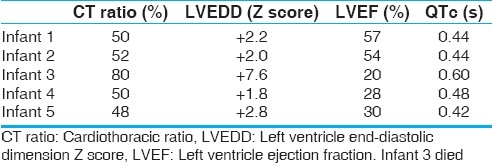

All cases received inotropic support including intravenous infusion of dopamine, dobutamine, and milrinone. Mechanical ventilation was continued in 1 patient. Anti-heart failure therapy including digoxin, frusemide, ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) inhibitor was started in all cases. All infants received 1 packed cell transfusion (15 mL/kg). The patient responded to these drugs with only slight symptomatic improvement. When hypocalcemia was confirmed, calcium was started as continuous intravenous infusion (dose 100–200 mg/kg/day) till serum calcium normalized, after which it was switched to oral calcium in the same dose. Injection magnesium sulfate (50%) (0.1 mL/kg) was given intramuscularly to all infants for 3 days. Injection vitamin D (cholecalciferol) was given intramuscularly (600,000 IU) followed by oral maintenance dose of 400 units/day for 6 months. All except 1 infant responded dramatically [Table 3]. Within 48 h of treatment for hypocalcemia, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium values were restored. QTc shortened to normal value. One infant, who was brought in multiorgan failure, remained in refractory shock. His renal functions and liver functions continued to deteriorate. Peritoneal dialysis was started in view of poor urine output. He suffered hypoxic brain damage with evidence of brainstem dysfunction. He had sudden cardiac arrest on third day of admission and could not be revived. Other infants were discharged in medium of 1 week with echocardiography showing significant improvement of LV function with median ejection fraction of 33% (range, 20-57%). On discharge oral decongestants, ACE inhibitors, calcium, and vitamin D supplementation were continued. On follow-up, serum calcium level remained normal in all the surviving infants. Median LV ejection fraction improved to 53% (range, 36–60%). LV size returned to normal range at a median of 2 months (1–4 months) from presentation.

Table 3.

Clinical status at discharge

DISCUSSION

Dilated cardiomyopathy in children have been well studied.[9–11] Myocardial dysfunction in patients with hypocalcemia is well described in the literature.[5–8,12] Hypocalcemia causes decreased myocardial contractility, leading to CHF, hypotension, and angina. Acute hypocalcemia causes prolongation of the QT interval, which may lead to ventricular dysrhythmias. Children have also been reported to develop heart failure in hypoparathyroidism.[4,13,14] However, there are only scattered case reports of hypocalcemia-related myocardial dysfunction that improved after treatment with therapeutic dose of vitamin D and calcium. Maiya et al.[15] reported first series of 16 cases of cardiomyopathy in children associated with vitamin D deficiency leading to hypocalcemia. Recently Tomar et al.[7] reported a series of 15 infants who were admitted with diagnosis of hypocalcemia cardiomyopathy, who responded dramatically to treatment with vitamin D and calcium, and cardiac function returned to normal within months. However, cardiogenic shock attributable to hypocalcemia is not well recognized. This series of 5 patients showed the surprising severity of hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy, seldom reported earlier. All the patients presented with cardiogenic shock and metabolic acidosis and required ionotropic support or mechanical ventilation. All infants were profoundly hypocalcemic, serum parathyroid hormone levels were uniformly raised and initial calcium levels were low, primarily due to vitamin D deficiency, which was present in all except one case. All infants except one responded dramatically to therapeutic doses of vitamin D and calcium. Clinical presentation, investigations, and dramatic response to treatment with vitamin D and calcium strongly support hypocalcemia being cause of severe cardiomyopathy leading to cardiogenic shock.

CONCLUSIONS

Thus, we conclude that in any case of cardiogenic shock in infancy, without structural heart disease, hypocalcemia should be included in the differential diagnosis and must be investigated as this is a reversible cause of cardiomyopathy, if proper resuscitation measures can be instituted simultaneously.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Levine SN, Rheams CN. Hypocalcemic heart failure. Am J Med. 1985;78:1033–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price DI, Stanford LC, Jr, Braden DS, Ebeid MR, Smith JC. Hypocalcemic rickets: An unusual cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24:510–2. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-0251-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown J, Nunez S, Russell M, Spurney C. Hypocalcemic rickets and dilated cardiomyopathy: Case reports and review of literature. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30:818–23. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9444-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altunbaş H, Balci MK, Yazicioğlu G, Semiz E, Ozbilim G, Karayalçin U. Hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy due to untreated hypoparathyroidism. Horm Res. 2003;59:201–4. doi: 10.1159/000069324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uysal S, Kalayci AG, Bysal K. Cardiac function in children with vitamin D deficiency rickets. Pediatr Cardiol. 1999;20:283–6. doi: 10.1007/s002469900464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olgun H, Ceviz N, Ozkan B. A case of dilated cardiomyopathy due to nutritional vitamin D deficiency rickets. Turk J Pediatr. 2003;45:152–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomar M, Radhakrishnan S, Shrivastava S. Myocardial dysfunction due to hypocalcaemia. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:781–3. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0117-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rimailho A, Bouchard P, Schaison G, Richard C, Auzépy P. Improvement of hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy by correction of serum calcium level. Am Heart J. 1985;109:611–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ushasree B, Shivani V, Venkateshwari A, Jain RK, Narsimhan C, Nallari P. Epidemiology and genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy in the Indian context. Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63:288–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Towbin JA, Lowe AM, Colan SD, Sleeper LA, Orav EJ, Clunie S, et al. Incidence, causes, and outcomes of dilated cardiomyopathy in children. JAMA. 2006;18(296):1867–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daubeney PE, Nugent AW, Chondros P, Carlin JB, Colan SD, Cheung M, et al. National Australian Childhood Cardiomyopathy Study. Clinical features and outcomes of childhood dilated cardiomyopathy: Results from a national population-based study. Circulation. 2006;114:2671–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gulati S, Bajpai A, Juneja R, Kabra M, Bagga A, Kalra V. Hypocalcemic heart failure masquerading as dilated cardiomyopathy. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68:287–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02723209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kudoh C, Tanaka S, Marusaki S, Takahashi N, Miyazaki Y, Yoshioka N, et al. Hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy in a patient with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism. Intern Med. 1992;31:561–8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.31.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avramides DA, Ionitsa SS, Panou FK, Ramos AN, Koutmos ST, Zacharoulis AA. Dilated cardiomyopathy and hypoparathyroidism: Complete recovery after hypocalcemia correction. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2003;44:150–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maiya S, Sullivan I, Allgrove J, Yates R, Malone M, Brain C, et al. Hypocalcemia and vitamin D deficiency: An important but preventable cause of life threatening infant heart failure. Heart. 2008;94:581–4. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.119792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]