Abstract

Changes in intracellular Ca2+ are central to the function of smooth muscle, which lines the walls of all hollow organs. These changes take a variety of forms, from sustained, cell-wide increases to temporally varying, localized changes. The nature of the Ca2+ signal is a reflection of the source of Ca2+ (extracellular or intracellular) and the molecular entity responsible for generating it. Depending on the specific channel involved and the detection technology employed, extracellular Ca2+ entry may be detected optically as graded elevations in intracellular Ca2+, junctional Ca2+ transients, Ca2+ flashes, or Ca2+ sparklets, whereas release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores may manifest as Ca2+ sparks, Ca2+ puffs, or Ca2+ waves. These diverse Ca2+ signals collectively regulate a variety of functions. Some functions, such as contractility, are unique to smooth muscle; others are common to other excitable cells (e.g., modulation of membrane potential) and nonexcitable cells (e.g., regulation of gene expression).

Ca2+ signals in smooth muscle include Ca2+ sparks (mediated by RyRs), Ca2+ puffs (IP3Rs), Ca2+ waves (IP3Rs/RyRs), junctional Ca2+ transients (P2X1Rs), Ca2+ flashes (VDCCs), and Ca2+ sparklets (VDCCs).

SMOOTH MUSCLE

Smooth muscle cells form a continuous layer that lines the walls of the hollow organs of the body, such as blood vessels, intestines, urinary bladder, airways, lymphatics, penis, and uterus. A defining feature of smooth muscle cells is their ability to contract. This property reflects the excitable nature of these cells, which allows for membrane potential-dependent influx of calcium (Ca2+) and the Ca2+-dependent formation of cross-bridges between myosin and actin—the two major contractile proteins that drive contraction. The contractile property of smooth muscle plays an important functional role in these organs, notably by allowing dynamic changes in luminal volume. These changes may regulate the translational movement of the organ’s contents, such as in the gastrointestinal tract, where the peristaltic action caused by sequential contraction of smooth muscle segments is responsible for the movement of food, and the urinary bladder, where smooth muscle in the wall relaxes during filling and contracts forcefully to expel urine during micturition. Uterine smooth muscle plays a similar role, relaxing during gestation to accommodate fetal growth and contracting vigorously during parturition. In the vasculature, the contractility of smooth muscle in the vessel wall is a primary determinant of blood pressure, which in turn controls blood flow and the distribution of nutrients and oxygen throughout the body.

Ca2+ SIGNALS IN SMOOTH MUSCLE

Smooth muscle contractility, and therefore hollow organ function, is regulated by changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). These changes may take a variety of forms, the simplest of which is a “global” (cell-wide) increase of the type associated with Ca2+-triggered actin-myosin cross-bridge formation and contraction. However, changes in intracellular Ca2+ may also be highly localized and often include a temporal component. Thus, Ca2+ changes may be sustained or transient, stationary or moving, or regularly repeating (Berridge 1997; Sanders 2001).

The nature of the Ca2+ signal depends to a large extent on the molecular mechanism responsible for generating it. Broadly speaking, there are two major mechanisms by which [Ca2+]i is raised in smooth muscle: (1) entry of Ca2+ from the extracellular space, and (2) release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Influx of extracellular Ca2+ is mediated by ion channels in the plasmalemmal membrane, the most prominent of which is the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (VDCC). Nonselective cation channels, such as transient receptor potential (TRP) channels and ionotropic purinergic (P2X) receptors, are also potentially important extracellular Ca2+ entry pathways in smooth muscle cells. Although a number of intracellular organelles take up and release Ca2+, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) represents the largest pool of releasable Ca2+ in smooth muscle cells. In response to a variety of stimuli, Ca2+-release channels in the SR, namely ryanodine receptors (RyR) and inositol trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), mediate efflux of Ca2+ from the SR into the cytoplasm of the cell.

IMAGING INTRACELLULAR Ca2+

Fluorescence, a property that allows certain molecules to absorb specific wavelengths of light and release energy in the form of light at a longer wavelength, has been exploited to produce numerous fluorescent indicators, including Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dyes. The fluorescence properties of Ca2+-sensitive indicators change when Ca2+ is bound; thus, such dyes can be used to detect intracellular Ca2+ levels. Ion fluxes in smooth muscle can occur very rapidly—often in the millisecond range. This property has motivated the development of a number of very rapid fluorescent dyes that enable detection of such changes in ion concentrations with high temporal resolution.

Fluorescent dyes can be loaded into cells by microinjection, but are more commonly introduced by incubating isolated smooth muscle cells or intact tissue with the membrane-permeant acetoxymethyl (AM) ester of the dye. The AM form is readily taken up by cells, but is acted on by intracellular esterases that cleave the ester bond to release the free anion, which is not membrane permeant and is thus retained within the cell. Most fluorescent Ca2+ indicators are based on fluorophore-conjugated derivatives of the Ca2+ chelator, BAPTA (bis-[o-amino-phenoxy]-ethane-N,N,N′N′-tetraacetic acid), which is used for both ratiometric and nonratiometric Ca2+ applications (Tsien 1980). Ratiometric dyes are used to measure the intracellular concentration of Ca2+. These dyes show a shift in the excitation (e.g., Fura-2) or emission (e.g., indole-1) spectrum according to the concentration of free or unbound Ca2+. From the ratio of bound and unbound Ca2+, the free intracellular Ca2+ concentration can be determined. Nonratiometric dyes, such as those in the Fluo family, show an increase in fluorescence quantum yield or intensity on binding Ca2+ and are useful for detecting qualitative changes in Ca2+ levels. Although nonratiometric dyes are not usually used for quantitative Ca2+ measurements, methods have been developed to calculate Ca2+ concentrations using single-wavelength fluorescence signals (Jaggar et al. 1998a; Maravall et al. 2000). One advantage of ratiometric dyes is that the ratio normalizes fluorescence variations caused by uneven cell thickness, dye distribution, dye leakage, or photobleaching—problems that are common to nonratiometric dyes. A disadvantage of ratiometric dyes is that they require excitation in the UV range. Some parameters to consider when selecting a fluorescent dye include (1) ion specificity, (2) dissociation constant (Kd), (3) hardware suitability (excitation and emission spectra), (4) fluorescence intensity, (5) availability as an AM ester, and (6) sensitivity to photobleaching.

Ca2+ signals are typically imaged using laser-scanning confocal microsopes. In its simplest form, a confocal microscope system comprises three main components: (1) a light source; (2) optical and electronic components to manipulate, display, and analyze signals; and (3) a microscope. Lasers, coupled to either upright or inverted microscopes, are commonly used as the light source for confocal microscopes. Although gas lasers (e.g., Ar-ion, Kr-ion, HeNe) provide numerous lasing lines from UV to red, and are well suited for optimal excitation of fluorescent probes, solid-state lasers are increasingly being used because they offer the advantages of longer lifetime, lower power consumption, and compact size.

To record very rapid events or determine the kinetics of a Ca2+ event by confocal microscopy, researchers have typically measured Ca2+ fluxes using a line-scanning procedure. In line-scan mode, a single line is repeatedly scanned across the cell for a period of time. Each line is then aligned to form an image that is a plot of fluorescence along the scanned line versus time (Fig. 1). Although line scans are still used, the development of very sensitive CCD (charge-coupled device) cameras and rapid Ca2+-sensitive dyes allows laser-scanning confocal systems to routinely achieve detailed spatial and temporal resolution, which is crucial for determining the origin of a Ca2+ event.

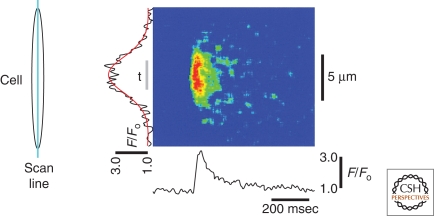

Figure 1.

Line-scan imaging. The image shown demonstrates the time course of fractional fluorescence (F/F0; bottom) and spatial distribution of the Ca2+ spark (left) fitted to a Gaussian distribution (red line). Gray bar labeled “t” indicates the region over which the fluorescence time course was averaged. Scan lines are displayed vertically in a continuous manner. (Inset) Orientation of scanning line. (Adapted from Bonev et al. 1997; reprinted with permission from The American Physiological Society © 1997.)

Confocal microscopy systems can also be used to measure changes in cellular Ca2+ caused by activation of photoprotected (“caged”) compounds. In this technique, the concentration of ions, signaling molecules, or other biologically active compounds can be instantaneously changed by UV stimulation of cells loaded with their caged equivalent. The resulting changes in intracellular Ca2+ can be monitored using the same system. By employing caged Ca2+ or Ca2+-releasing compounds (e.g., IP3), this approach can also be used to directly elevate Ca2+ within a cell. This uncaging strategy facilitates the study of a particular signaling step independent of preceding steps in the signaling pathway.

Specialized techniques have also been developed for measuring Ca2+ signals in specific subcellular compartments. One such technique is total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, which is used to selectively visualize the area immediately beneath the plasmalemma. In TIRF microscopy, an evanescent wave is created by the reflection of a laser beam at the interface between a glass coverslip and the cytoplasm of cells attached to the coverslip (Fig. 2). Because TIRF measurements usually use nonratiometric dyes, they have the same limitations noted above for these fluorophores.

Figure 2.

TIRF microscopy. (A) A schematic of the TIRF imaging system. A, adjustable rectangular knife-blade aperture; BE, beam expander; FL, focusing lens; BF, barrier filter; DM, dichroic mirror; CCD, charge-coupled device. (B) Imaging membrane-proximate fluorescent Ca2+ signals near an open channel by TIRF microscopy. (C) A single frame of a TIRF microscopy video image illustrating Ca2+ signals generated by three channels within an 80 × 80-μm patch of membrane. Increasing Ca2+ concentrations are indicated by both “warmer” colors and height. (Adapted from Demuro and Parker 2004; reprinted with permission from Elsevier © 2004.)

Ca2+ SIGNALS FROM OUTER SPACE: Ca2+ INFLUX

Signals Mediated by VDCCs

Membrane potential depolarization activates VDCCs—the major contributors to increases in [Ca2+]i. VDCCs are multisubunit complexes comprising a pore-forming α1 subunit and regulatory β, α2δ, and γ subunits (Curtis and Catterall 1984; Hosey et al. 1987; Leung et al. 1987; Vaghy et al. 1987). Most of the functional properties of the VDCC channel, including voltage sensitivity, Ca2+ permeability, Ca2+-dependent inactivation, and sensitivity to pharmacological block by organic Ca2+ channel blockers, are attributable to the α1 subunit. The domain organization of the α1 subunit creates a pseudotetrameric structure in which the four repeat domains (I, II, III, IV), each composed of six transmembrane segments (S1–6) and intracellular amino- and carboxyl-termini (Catterall 2000; Jurkat-Rott and Lehmann-Horn 2004), are analogous to the individual subunits of structurally similar, tetrameric voltage-dependent potassium (K+) channels. The S4 transmembrane segments of each domain serve as voltage sensors; in response to changes in membrane potential, they move outward and rotate, producing a conformational change that opens the pore (Catterall 2000).

The pore-forming α1 subunit is expressed as multiple splice variants with different regulatory and biophysical properties. Additional molecular diversity is provided by four different, variably spliced β subunits (Birnbaumer et al. 1998), which further modify VDCC biophysical properties and regulate surface expression of the α1 subunit; properties of the VDCC complex may be additionally modulated by splice variants of the α2δ regulatory subunit (Angelotti and Hofmann 1996).

VDCC-mediated currents are characterized by high voltage of activation, large single-channel conductance, and slow voltage-dependent inactivation. VDCC-mediated currents also display a characteristic sensitivity to dihydropyridines (Reuter 1983), a class of drugs used clinically in the treatment of hypertension (Nelson et al. 1990; Snutch et al. 2001). In vascular and visceral smooth muscle, these dihydropyridine-sensitive currents are attributable to the expression of the L-type VDCC pore-forming α1C subunit (CaV1.2) (Keef et al. 2001; Moosmang et al. 2003; Wegener et al. 2004); but in some smooth muscle types, the α1D (CaV1.3) subunit is expressed as well (Nikitina et al. 2007). Of the four β subunits, only two—β2 and β3—are clearly detected at the protein level in smooth muscle, although mRNA for all four isoforms is expressed (Hullin et al. 1992; Murakami et al. 2003).

There is also evidence for the expression of a dihydropyridine-insensitive Ca2+ current in some smooth muscle types. This T-type (transient) current is mediated by CaV3 pore-forming α subunits—primarily the CaV3.1 isoform in smooth muscle (Bielefeldt 1999; Perez-Reyes 2003). Expression of T-type channels varies between different smooth muscle types, but their presence often goes undetected because of their low levels of expression or because they are obscured by the specific recording conditions used. Moreover, the negative steady-state inactivation property of these channels results in their being half-inactivated at about –70 mV. Therefore, over the range of smooth muscle resting membrane potential (–50 to –30 mV), T-type channels may be completely inactivated. Because of these gating properties, the importance of T-type currents in the regulation of smooth muscle membrane potential is a matter of controversy. However, there is evidence from the rabbit urethra that, at least in this tissue, T-type channels regulate action potential frequency (Bradley et al. 2004). It also has been suggested that voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in smooth muscle with a T-type pharmacology may arise because of a CaV3.1 (and/or CaV3.2) splice variant with a more depolarized activation voltage (Kuo et al. 2010).

Three different Ca2+ signals mediated by VDCCs have been identified in smooth muscle: (1) global elevations in intracellular Ca2+, (2) Ca2+ “flashes,” and (3) Ca2+ “sparklets.”

Global Ca2+ Signals

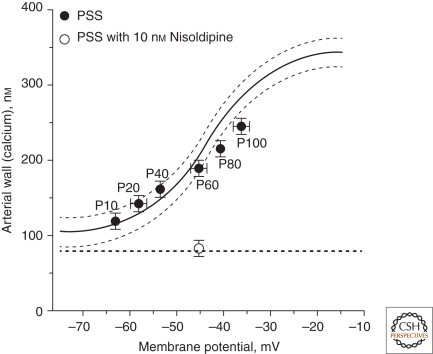

As the name suggests, global Ca2+ signals reflect changes in Ca2+ concentration that are essentially uniform throughout the cell. In smooth muscle, depolarization of the membrane by ∼15 mV from its resting potential (approximately –50 to –40 mV) elevates global Ca2+ to ∼300–400 nM, whereas hyperpolarization by ∼15 mV lowers Ca2+ to ∼100 nM. These signals are typically monitored using ratiometric dyes (e.g., Fura-2), which are ideally suited to measuring Ca2+ concentration over this range (Kd ∼300 nM). Thus, by modulating the steady-state open probability of VDCCs, slow changes in membrane potential can have profound, sustained effects on global intracellular Ca2+. This is illustrated in Figure 3, which shows that the membrane potential depolarization that accompanies elevation of intraluminal pressure from 60 mmHg (Fig. 3A) to 100 mmHg (Fig. 3B) increases the global intracellular Ca2+ concentration in the vascular wall. Inhibition of VDCC channels with nisoldipine decreases global [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3C). Changes in global Ca2+ are accompanied by changes in vascular diameter, underscoring the importance of global Ca2+ in regulating the contractile state of smooth muscle (see below).

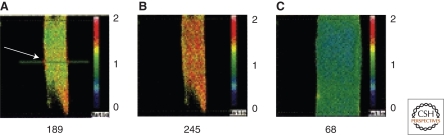

Figure 3.

Global Ca2+. Ca2+ images obtained from a rat basilar artery pressurized to (A) 60 mmHg, (B) 100 mmHg, and (C) 100 mmHg in the presence of nisoldipine. The numbers below each panel correspond to the Ca2+ concentration in the smooth muscle of the vascular wall, calculated from the ratio of Fura-2 fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm. Note contraction and dilation in B and C, respectively, relative to A. (Adapted from Knot and Nelson 1998; reprinted with permission from The Journal of Physiology © 1998.)

Ca2+ Flashes

Some types of smooth muscle (e.g., urinary bladder, gallbladder, ureter) show action potentials. These rapid, transient changes in membrane potential, which show a characteristic temporal profile, are unique to excitable cells. However, unlike other excitable cells, such as neurons and cardiac myocytes, where action potentials are initiated by activation of channels that predominantly mediate sodium (Na+) influx, the upstroke of the action potential in smooth muscle reflects massive Ca2+ entry through VDCCs. The resulting rapid elevation of global intracellular Ca2+ can be detected optically as a Ca2+ flash that brightly and briefly lights up cells loaded with fluorescent Ca2+ indicators. A recording of a Ca2+ flash in urinary bladder smooth muscle is shown in Figure 4. Ca2+ flashes can be evoked by electrical field stimulation, but also occur spontaneously (as in the example shown), likely reflecting the spontaneous release of neurotransmitters from sympathetic (e.g., mesenteric arteries) or parasympathetic (e.g., urinary bladder) nerve terminals (Klockner and Isenberg 1985; Heppner et al. 2005). Note that in this example, Ca2+ was simultaneously elevated in two adjacent cells, indicating that these events may be coupled.

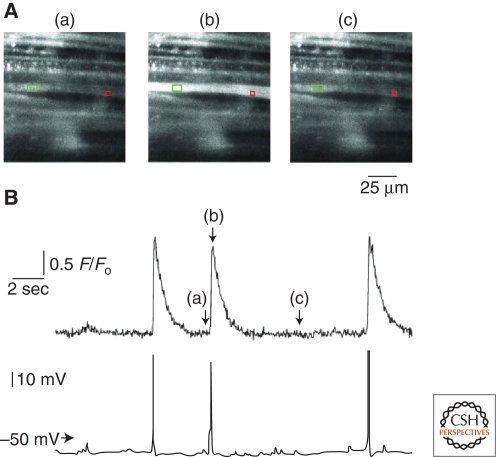

Figure 4.

Ca2+ flashes. (A) Selected images recorded before (a), during (b), and after (c) a spontaneous action potential in a smooth muscle bundle loaded with Fluo-4 and impaled with a microelectrode (green rectangle). (B) Simultaneous recordings of changes in Ca2+-activated fluorescence (upper trace) and voltage (lower trace) from a single bundle of urinary bladder smooth muscle. Changes in Ca2+-activated fluorescence were measured from the red box in A; the letters a, b, and c denote the times at which the correspondingly labeled images in A were acquired. Note that each of the three action potentials induced a simultaneous increase in Ca2+-activated fluorescence. (Adapted from Heppner et al. 2005; reprinted with permission from The Journal of Physiology © 2005.)

Ca2+ Sparklets

Cheng and colleagues first measured the local Ca2+ signal caused by the opening of a single L-type VDCC in cardiac muscle (Wang et al. 2001b), and referred to these events as Ca2+ sparklets. Ca2+ sparklets are also present in vascular smooth muscle (Fig. 5), where they are detected by TIRF microscopy as highly localized, dihydropyridine-sensitive, subplasmalemmal Ca2+-release events reflecting the activity of an individual channel or cluster of channels (Navedo et al. 2005). The average area of a Ca2+ sparklet is ∼0.8 µm2 or ∼0.08% of the surface membrane of a typical arterial smooth muscle cell (Santana et al. 2008). Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ sparklet sites is quantal, and the size of a given Ca2+ sparklet depends on the number of quanta activated. One quantal unit of Ca2+ release elevates [Ca2+]i by about 35 nm. The specific locations of Ca2+ sparklets vary between cells, but within a cell, Ca2+ sparklets are predominantly stationary events that occur in specific regions of the sarcolemmal membrane (Fig. 5A–C). Both low- and high-activity Ca2+ sparklet sites have been described. The frequency of the latter type of event, termed a persistent sparklet, is increased by activation of protein kinase C (PKC), which recruits previously silent sites and increases the frequency of low-activity sites (Fig. 5D).

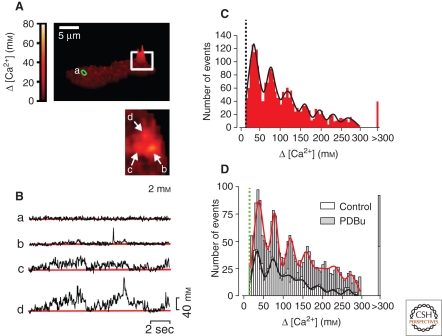

Figure 5.

Ca2+ sparklets. (A) Surface plot of Ca2+ imaged in a freshly isolated arterial myocyte. (Inset) Higher magnification view of boxed area showing three active Ca2+ sparklet sites (2 mm extracellular Ca2+). (B) Traces showing time course of changes in Ca2+ at sites a–d. (C) Amplitude histogram of Ca2+ sparklets (20 mm extracellular Ca2+). (D) Amplitude histogram of Ca2+ sparklets (2 mm extracellular Ca2+) in the absence and presence of the PKC activator phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu). Solid lines in C and D are best fits to a Gaussian function. (Adapted from Navedo et al. 2005; reprinted with permission from The National Academy of Sciences © 2005.)

In heart muscle, where local coupling of Ca2+ influx through single VDCCs to RyRs is central to excitation-contraction coupling (Cannell et al. 1995; Lopez-Lopez et al. 1995), a Ca2+ sparklet can activate four to six nearby RyRs to cause a Ca2+ spark (see below). However, there is no evidence for this direct VDCC-to-RyR communication in smooth muscle. Instead, Ca2+ currents through VDCCs appear to activate RyRs indirectly through elevations in global Ca2+ and SR Ca2+ load (Collier et al. 2000; Herrera and Nelson 2002; Wellman and Nelson 2003; Essin and Gollasch 2009).

Signals Mediated by Store-Operated Ca2+ Channels

Extracellular Ca2+ influx in response to depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores, a process termed store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), is known to play an important role in a number of cell types, notably nonexcitable cells. However, the molecular mechanism underlying this coupling long remained elusive. Recent seminal work by a number of independent groups effectively resolved this question, clearly identifying ubiquitously expressed STIM proteins (Liou et al. 2005; Roos et al. 2005) as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ sensors, and members of the Orai family (Feske et al. 2006; Vig et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006) of transmembrane proteins as the entities responsible for mediating Ca2+ entry (reviewed in Varnai et al. 2009). These researchers showed that, in response to a decrease in ER Ca2+ concentrations, the low-affinity Ca2+-binding STIM proteins aggregate to form discrete plasmalemmal-proximate clusters that tether Orai proteins. This physical coupling activates Orai, which is a highly selective Ca2+ channel, thereby promoting extracellular Ca2+ entry. The identification of the STIM-Orai mechanism has sparked renewed interest in investigating SOCE in smooth muscle (reviewed in Wang et al. 2008). These studies, most of which have been performed using cultured smooth muscle cells, have consistently shown that STIM and Orai family members are expressed in smooth muscle, and, under the conditions tested, are capable of functionally coupling store depletion to extracellular Ca2+ entry (Peel et al. 2006, 2008; Takahashi et al. 2007; Ng et al. 2010; Park Hopson et al. 2011). It has also been suggested that, in addition to promoting Orai activity, STIM1 negatively regulates VDCCs (Wang et al. 2010). Some recent studies have provided evidence for STIM-Orai coupling in native smooth muscle preparations, and have suggested a role for this mechanism in hypertension (Giachini et al. 2009, 2010). An optical signature of Orai-mediated Ca2+ influx has not been defined and additional research will be required to definitively establish the physiological relevance of this pathway in native smooth muscle tissues.

Signals Mediated by Nonselective Cation Channels

In contrast to VDCCs, which show a high selectivity for Ca2+ ions over monovalent cations, nonselective cation channels typically also allow influx of extracellular Na+. Although channels of this type are permeable to Ca2+ and thus directly increase [Ca2+]i to some degree, in many if not most cases, their major impact on [Ca2+]i is indirect through Na+-dependent membrane potential depolarization and activation of VDCCs. Several types of Ca2+-permeable, nonselective cation channels are present in smooth muscle, including receptor-activated channels, mechanosensitive channels, tonically active channels, and channels activated by SR Ca2+ store depletion.

Receptor-Activated Cation Channels

Of the various nonselective cation channels expressed in smooth muscle, only the ATP-gated P2X receptor (P2XR) is clearly associated with an optically identifiable Ca2+ signal. The functional P2XR complex is thought to be a trimer (Aschrafi et al. 2004)—an unusual structural arrangement in ion-channel space where tetramers dominate. Each subunit contains intracellular amino- and carboxyl-termini and two membrane-spanning domains that are connected by a large extracellular domain (Khakh 2001; North 2002). Binding of ATP (three molecules per complex) to a site in the large extracellular domain induces a conformational change that results in rapid (milliseconds) opening of the pore.

These Ca2+- and Na+-permeable channels (Benham and Tsien 1987; Schneider et al. 1991) mediate a rapid local influx of Na+ and Ca2+ at nerve–muscle junctions following activation by neurally released ATP (Lamont and Wier 2002; Lamont et al. 2006). The influx of Na+ and Ca2+ creates an excitatory junction potential (EJP) that contributes directly to the increase in postjunctional excitability. Multiple lines of evidence, including studies using knockout mice, indicate that the P2X1 receptor is the predominant P2X receptor isoform expressed in smooth muscle (Mulryan et al. 2000; Vial and Evans 2002; Lamont et al. 2006; Heppner et al. 2009).

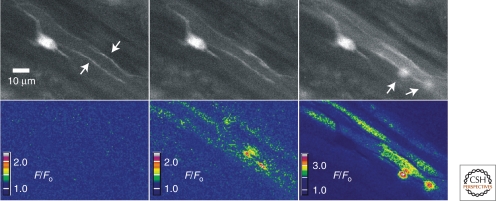

Although most of the excitatory junction current (EJC) associated with P2X1 receptor activation is carried by the more abundant Na+ ions, Ca2+ influx is substantial. This influx can be detected optically in the form of local elementary purinergic-induced Ca2+ transients (Fig. 6). These events have been described in vas deferens (Brain et al. 2002), mesenteric arteries (Lamont and Wier 2002), and urinary bladder (Heppner et al. 2005), where they have been termed neuroeffector Ca2+ transients (NCTs), junctional Ca2+ transients (jCaTs), and nerve-evoked elementary purinergic Ca2+ transients, respectively. The kinetic properties of these purinergic Ca2+ signals are similar to one another and are clearly distinct from those of other local Ca2+ transients (Hill-Eubanks et al. 2010).

Figure 6.

Elementary purinergic Ca2+ transients recorded from urinary bladder smooth muscle. Transient events were evoked by electrical field stimulation (2-sec train, 5 Hz; 37°C) in bladder strips loaded with Fluo-4 and scanned at a rate of 30 images/sec. The top three images illustrate nerve processes before (top panel, left, indicated by arrows) and after stimulation (middle and right panels). The three bottom panels illustrate color-coded ratios (F/F0) of the images above. Intracellular Ca2+ increases first in the nerve fibers, and then two local Ca2+ transients are detected (right panel, bottom right quadrant, indicated by arrows). The activity of Ca2+ transients continued throughout the duration of field stimulation. (Unpublished data from Mark Nelson.)

Other Nonselective Cation Channels

Smooth muscle cells express a number of nonselective cation channels of the TRP family. Although no signature signaling event associated with Ca2+ influx through TRP channels has been reported in the literature, given the relative selectivity of these channels for Ca2+ (and the high Ca2+ permeability and single-channel conductance of some TRP family members, notably TRPV), imaging methods that have been used to examine jCaT-like events (confocal microscopy) and/or VDCC-mediated sparklets (TIRF) may ultimately provide a means to optically detect Ca2+ influx through these channels.

Ca2+ SIGNALS FROM INNER SPACE: RELEASE OF Ca2+ FROM INTRACELLULAR STORES

The most important intracellular Ca2+ store in smooth muscle is the SR. Cytosolic Ca2+ is transported into the SR by the action of the SR/ER Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA). SERCA activity is negatively regulated by the protein phospholamban, a target of protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase G (PKG). On phosphorylation, the SERCA inhibitory activity of phospholamban is lost, increasing Ca2+ uptake and SR Ca2+ load. Free Ca2+ taken up by the SR is buffered by Ca2+-binding proteins, which retain transported Ca2+ and reduce the free Ca2+ concentration gradient, facilitating continued Ca2+ uptake from the cytoplasm (Pozzan et al. 1994).

Ca2+ sequestered in the SR may be delivered to the cytosol through RyRs and IP3 receptors in the SR membrane. Although these two channel types are phenotypically similar on a superficial level (both function to release Ca2+ from SR stores) they are very different molecular entities with distinctive regulatory features and characteristic Ca2+-release signatures.

Signals Mediated by RyRs: Ca2+ Sparks

There are three RyR subtypes (RyR1-3), each of which is expressed at varying levels in different smooth muscle tissues (Neylon et al. 1995; Yang et al. 2005; Prinz and Diener 2008). RyRs are large tetrameric complexes formed from ∼560-kDa subunits. Each subunit contains four membrane-spanning domains, a large cytosol-facing amino-terminal region containing the Ca2+-binding site as well as binding sites for numerous accessory proteins, and a short SR-luminal carboxy-terminal domain (reviewed in Zalk et al. 2007; Lanner et al. 2010).

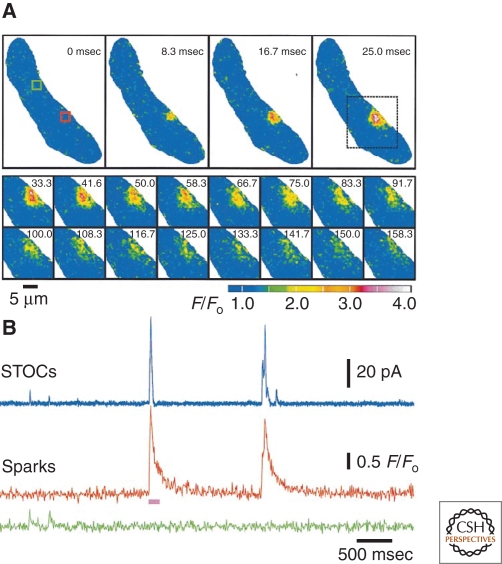

Ca2+ flux through ryanodine receptors is detectable in the form of elementary release events termed Ca2+ sparks. First discovered in cardiac muscle (Cheng et al. 1993) and subsequently identified in skeletal (Klein et al. 1996) and smooth (Nelson et al. 1995) muscle, a Ca2+ spark represents the opening of a few (likely four to six) RyR channels in the SR membrane (Cheng and Lederer 2008). Ca2+ sparks have been detected in a wide variety of smooth muscle types, including those from arteries (Nelson et al. 1995), portal vein (Mironneau et al. 1996; Gordienko and Bolton 2002), urinary bladder (Herrera et al. 2001), ureter (Burdyga and Wray 2005), airway (Sieck et al. 1997), and the gastrointestinal tract (Gordienko et al. 1998). Ca2+ sparks in arterial smooth muscle can be detected in isolated myocytes as well as in intact pressurized arteries. Ca2+ sparks are rapid, transient, stationary events. The rise time of sparks in vascular smooth muscle and urinary bladder smooth muscle is ∼20–40 msec (Nelson et al. 1995; Herrera et al. 2001); their spatial spread is ∼12.6 µm, and this spread corresponds to ∼1% of the surface membrane. The duration (half-time) of these events is ∼50–60 msec; this contrasts with nerve-evoked purinergic Ca2+ transients, which have half-times of ∼110–145 msec (Brain et al. 2002; Lamont and Wier 2002; Heppner et al. 2005). Current evidence indicates that smooth muscle Ca2+ sparks are attributable to activation of RyR2, although both RyR1 and RyR3 may influence spark activity (Vaithianathan et al. 2010).

In smooth muscle, localized increases in Ca2+ associated with Ca2+ sparks activate closely juxtaposed large-conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels in the plasma membrane. The Kd of BKCa channels for Ca2+ is ∼20 µm at the physiological membrane potential of –40 mV. A single spark causes a local increase of [Ca2+]i of 10–30 µm and activates about 30 nearby BKCa channels, increasing their open probability by approximately 100-fold (Jaggar et al. 2000; Perez et al. 2001). In smooth muscle from adult animals, there is a one-to-one relationship between sparks and BKCa channel–mediated transient outward currents, indicating that all spark sites are functionally coupled to BKCa channel clusters. In current-clamp mode, activation of BKCa channels by a single spark causes about a 20-mV hyperpolarization (Jaggar et al. 1998b).

Stimuli that increase SR Ca2+ load increase the frequency of Ca2+ sparks, but sparks also occur spontaneously. The outward currents associated with this latter activity are termed “spontaneous transient outward currents” or “STOCs” (Benham and Bolton 1986). An example depicting the time course and decay kinetics of a single Ca2+ spark event is presented in Figure 7A. Simultaneous electrophysiological recordings and traces showing analyzed Ca2+ signals (Fig. 7B) highlight the one-to-one relationship between sparks and STOCs.

Figure 7.

Ca2+ sparks in an isolated rat basilar artery myocyte. (A) (Top) Two-dimensional confocal images of an entire smooth muscle cell showing the time course of the fractional increase in Fluo-3 fluorescence (F/F0) of a typical Ca2+ spark. (Bottom) Images obtained from the region of interest in the top-right panel (dotted box) depicting spark decay. Pseudocolor denotes relative Ca2+ levels as indicated by the bar. (B) Simultaneous measurements of STOCs and sparks at –40 mV highlighting the temporal association between the events. The pink bar below the sparks trace corresponds to the time period imaged in A. (Adapted from Perez et al. 1999; reprinted with permission from The Rockefeller University Press © 1999.)

In addition to activating BKCa channels to produce STOCs, Ca2+ sparks can also activate Ca2+-sensitive chloride (ClCa) channels to produce spontaneous transient inward currents (STICs) (Hogg et al. 1993). Where BKCa and ClCa channels coexist, spontaneous transient outward/inward currents (STOICs) are produced (ZhuGe et al. 1998; Jaggar et al. 2000; Wellman and Nelson 2003). Both hyperpolarizing (STOCs) and depolarizing currents (STICs) modulate membrane potential and excitability, with STOCs being inhibitory and STICs being excitatory.

Signals Mediated by IP3Rs: Ca2+ Waves

There are three IP3 receptor subtypes (IP3R1-3), each of which is expressed at varying levels in different smooth muscle tissues (Newton et al. 1994; Tasker et al. 1999; Boittin et al. 2000; Grayson et al. 2004). IP3Rs are large homo- or heterotetrameric complexes formed from approximately 2700 to 2800 amino acid subunits. Each subunit contains six membrane-spanning domains, a large cytosol-facing amino-terminal region containing the IP3 binding site, and a short cytosolic carboxy-terminal domain. The pore of the channel is formed by the coassociation of transmembrane domains 5 and 6 from each of the four subunits (Foskett et al. 2007).

Ca2+ release by IP3Rs is regulated by two second messengers: IP3 and Ca2+. The prototypical signaling pathway that leads to elevation of IP3 is activation of Gαq/11-type G protein-coupled receptors. Among the most prominent agonists of this pathway in smooth muscle are neurohumoral vasoconstrictors. Activation of this pathway stimulates phospholipase C, resulting in hydrolysis of membrane-associated phosphoinositide 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into IP3 and diacyclglycerol. The IP3 generated by this pathway binds IP3Rs and promotes channel gating, releasing Ca2+ into the cytosol. The Ca2+ released by IP3Rs can reciprocally modulate IP3R activity in two ways: as Ca2+ rises from low nanomolar basal levels to low micromolar levels in the vicinity of the channel, it activates IP3Rs; at higher local levels, the channel becomes inactivated. These activation/inactivation properties together with regulation of channel function by multiple interacting factors, allow IP3Rs to generate a large variety of temporally and spatially modulated Ca2+-signaling patterns within the cell (Foskett et al. 2007).

In some smooth muscle types, IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release is transient and localized. For example, smooth muscle cells from colon and portal vein show spontaneous Ca2+ spark-like events that are enhanced by IP3 production and eliminated by IP3R blockade (Bayguinov et al. 2000; Gordienko and Bolton 2002). These Ca2+ release events, termed Ca2+ “puffs,” have a biophysical signature (e.g., kinetics, magnitude, spatial spread) that distinguishes them from the RyR-mediated Ca2+ sparks that are prominent in most other smooth muscle types (e.g., vascular smooth muscle, gallbladder, and urinary bladder) (Nelson et al. 1995; Herrera et al. 2001; Pozo et al. 2002). Although Ca2+ puffs are unitary events, they can act as initiation sites for intracellular Ca2+ waves and thereby contribute to global Ca2+ signals (Bootman and Berridge 1996; Thomas et al. 1998).

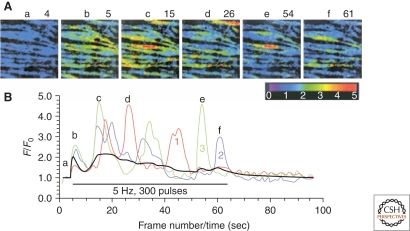

A Ca2+ wave, defined as an increase in [Ca2+]i that propagates across the entire smooth muscle cell from an initial site of release, is perhaps the most studied IP3R-mediated Ca2+-signaling event. First described by Iino in rat tail arteries (Fig. 8), Ca2+ waves are a common feature of vascular smooth muscle cells exposed to Gαq/11-coupled vasoconstrictor agonists, such as UTP (Jaggar and Nelson 2000) and norepinephrine (Iino et al. 1994; Boittin et al. 1999; Miriel et al. 1999; Ruehlmann et al. 2000), or electrical field stimulation of perivascular nerves.

Figure 8.

Ca2+ waves. (A) Two-dimensional pseudocolor confocal microscopic images of rat tail artery smooth muscle showing dynamic, recurrent changes in intracellular Ca2+ (measured by changes in the intensity of Fluo-3 fluorescence) following electrical stimulation of perivascular sympathetic nerves. Six of 96 consecutive frames collected at a rate of one frame per second are shown. (B) Red, blue, and green lines depict changes in fluorescence intensity as a function of time (a–f in A) in three selected regions of interest (white boxes in a). (Adapted from Iino et al. 1994; reprinted with permission from The EMBO Journal © 1994.)

In the current view, Ca2+ waves reflect the activation/inactivation properties of IP3Rs, and arise through a regenerative Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) mechanism. Ca2+ released from the SR acts on successive adjacent IP3Rs or IP3R clusters in a cascading fashion, creating a leading edge of Ca2+ elevation that traverses the length of the cell. When Ca2+ waves propagate toward each other and collide, they cancel each other out because of depletion of SR Ca2+ stores on either side of the collision site (Stevens et al. 1999). Therefore, a continuous cycling of SR Ca2+ release and reuptake maintains the Ca2+ waveform. Ca2+ released from SR stores is sufficient for further release and maintenance of Ca2+ waves, indicating that the mechanism of smooth muscle Ca2+ wave propagation is independent of extracellular Ca2+ entry (Boittin et al. 1999; Jaggar and Nelson 2000; Peng et al. 2001; Heppner et al. 2002). Repeating IP3R-dependent Ca2+ signals may also take the form of whole-cell oscillations in [Ca2+]i.

The view of Ca2+ waves as strictly IP3R-mediated events oversimplifies the true situation. In actuality, Ca2+ waves arise in response to activation of IP3Rs and/or RyRs (Iino et al. 1994; Boittin et al. 1999; Hirose et al. 1999; Jaggar and Nelson 2000; Lee et al. 2002), and their properties as well as the relative contributions of IP3Rs and RyRs may differ depending on the nature of the stimulus or tissue context. In some cases, these events appear to exclusively reflect the activity of RyRs. One such example is provided by rat cerebral arteries, where Nelson and colleagues (Heppner et al. 2002) have found that Ca2+ waves are induced by caffeine, which acts on RyRs but not IP3Rs. Moreover, these events are insensitive to the nominally selective IP3R blockers, xestospongin C and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), but are completely eliminated by ryanodine. Interestingly, RyR-mediated Ca2+ signaling in this preparation is sharply dependent on pH. Increasing the pH of the bathing solution from 7.4 to 7.5 increased Ca2+ spark frequency by ∼50%; above this pH, Ca2+ waves came to predominate, increasing approximately threefold between pH 7.5 and pH 7.6 and doubling again at pH 7.7–7.8.

FUNCTIONAL CORRELATES OF Ca2+ SIGNALS

Contractility

Smooth muscle contraction is driven by Ca2+-calmodulin activation of myosin light chain kinase, which has a Ca2+ half-activation of ∼400 nm (Stull et al. 1998). The gain of smooth muscle contraction to Ca2+ can be adjusted through regulation of myosin light chain phosphatase (Somlyo and Somlyo 2003; Mizuno et al. 2008).

Global Ca2+

Membrane potential plays an important role in all excitable cells, including smooth muscle, where it regulates [Ca2+]i and thereby smooth muscle contraction. The resting membrane potential of smooth muscle is approximately –50 to –40 mV, which is positive to the equilibrium potential for K+ (EK). In arterial smooth muscle, this membrane potential is sufficient to increase the steady-state open probability of VDCCs, elevate global intracellular Ca2+ from ∼100 nm to ∼200 nm, and cause a tonic constriction (Knot and Nelson 1998). As noted above, membrane potential hyperpolarization to –60 mV lowers Ca2+ to about 100 nm, and depolarization to about –30 mV elevates global Ca2+ to ∼300–400 nm; these changes in global intracellular Ca2+ are sufficient to cause maximal dilation and constriction, respectively. The fundamental relationship between global Ca2+ and smooth muscle membrane potential is depicted in Figure 9, which also highlights the role of intravascular pressure as a physiological driver of changes in membrane potential. Oscillations in membrane potential caused by fluctuations in Ca2+ entry through VDCCs lead to vasomotion of the arterial wall.

Figure 9.

Intravascular pressure-membrane potential-[Ca2+]i relationships. Fundamental relationships among intravascular pressure (P10–P100, in mm Hg), membrane potential, and arterial wall Ca2+. (Adapted from Knot and Nelson 1998; reprinted with permission from The Journal of Physiology © 1998.)

Junctional Ca2+ Transients and Ca2+ Flashes

Nerve stimulation–evoked localized Ca2+ influx through P2X1R channels causes a depolarizing current carried by Na+ and Ca2+ ions that activates VDCCs; in urinary bladder smooth muscle, this manifests as a Ca2+ flash. Coordinated flash activity among smooth muscle cells in a bundle leads to a transient contraction. Thus, junctional Ca2+ transients mediated by P2X1Rs may indirectly modulate contraction by triggering VDCC activity.

The bursts of local elevations in intracellular Ca2+ provided by junctional Ca2+ transients also have the potential to trigger activation of proximate RyRs in the SR through a CICR mechanism. The best evidence for the existence of such a mechanism comes from studies of the vas deferens by Cunnane and coworkers (Brain et al. 2003). In this preparation, the magnitude of neurally evoked, ATP-induced Ca2+ transients was reduced by ∼45% by inhibition of RyRs with ryanodine. Moreover, treatment with caffeine to increase RyR activity produced a 16-fold increase in the frequency of neurally evoked junctional Ca2+ transients. Collectively, these results argue that the neurally evoked Ca2+ signal associated with extracellular Ca2+ influx triggers—and merges with—a RyR-mediated Ca2+ signal, creating an optically detectable signal that reflects a summation of the two separate transient release events. The more modest inhibitory effect of ryanodine on jCaTs in mesenteric arteries (∼13%) (Lamont and Wier 2002) and the apparent absence of an effect of ryanodine on purinergic Ca2+ transients in rat urinary bladder (Heppner et al. 2005) suggest a degree of variability among tissues and species. How (or if) this communication from P2X1Rs to RyRs influences the contractile behavior of smooth muscle is not clear. The additional increment of Ca2+ may sum with P2X1R and VDCC-mediated Ca2+ to augment the transient contraction. Alternatively, CICR-activated RyRs could, in theory, couple to BKCa channels to oppose contraction. Depending on the relative speed of IP3 production by concurrent activation of adrenergic or muscarinic receptors, it is also possible that Ca2+ influx through P2X1Rs could amplify local IP3R activation by IP3, a possibility that has not yet been explored experimentally.

Ca2+ Sparks

In cardiac and skeletal muscle, local Ca2+ entry through VDCCs activates proximate RyRs, producing Ca2+ sparks that summate to create a substantial increase in global Ca2+; thus, Ca2+ sparks play a dominant role in contraction in these tissues. In smooth muscle, the molecular architecture is much different, resulting in unique linkages that create a phenotypically opposite functional outcome. In particular, the close physical coupling between VDCCs and RyRs that characterizes striated muscle cells is absent in smooth muscle cells. In its place is a close linkage between the RyR and plasma membrane BKCa channels, which are not expressed in cardiac or skeletal muscle cells. As a result of this unique architecture, Ca2+ released by RyRs in the SR in the form of sparks activates juxtaposed BKCa channels, promoting an outward K+ current that hyperpolarizes the smooth muscle membrane and reduces VDCC activity. The resulting decrease in Ca2+ influx thus opposes VDCC-mediated smooth muscle contraction (Nelson et al. 1995; Perez et al. 1999; Jaggar et al. 2000). Under this scenario, Ca2+ influx through VDCCs initiates the BKCa channel-mediated feedback mechanism by enhancing RyR activity, by increasing global Ca2+ and SR Ca2+ stores (Collier et al. 2000; Herrera and Nelson 2002; Wellman and Nelson 2003; Essin and Gollasch 2009).

As is observed with P2X1 agonists, simultaneous activation of RyRs by rapid addition of high levels of the RyR activator, caffeine, can cause global Ca2+ transients and a transient contraction (Wellman and Nelson 2003).

Ca2+ Waves

Ca2+ waves normally occur asynchronously in smooth muscle cells. However, in some vascular beds, Ca2+ waves may synchronize in neighboring arterial myocytes to initiate vasomotion (Peng et al. 2001), supporting the idea that Ca2+ waves can supply the Ca2+ needed for smooth muscle contraction (Kasai et al. 1997; Boittin et al. 1999; Mufti et al. 2010). Alternatively, Ca2+ waves can influence contractility indirectly through activation of Ca2+-dependent ion channels located in the plasmalemmal membrane. For example, Ca2+ waves can activate ClCa channels to promote membrane depolarization leading to enhanced Ca2+ entry through VDCCs (Mironneau et al. 1996). Ca2+ waves can also activate BKCa channels, thereby promoting membrane potential hyperpolarization, closure of VDCCs, and induction of smooth muscle relaxation (Young et al. 2001). Thus, while information on Ca2+ waves in smooth muscle continues to accumulate, the physiological function of these Ca2+ signals remains uncertain.

Ca2+-DEPENDENT TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR ACTIVATION

Global Ca2+: Excitation-Transcription Coupling

Excitation-contraction coupling, in which depolarization induces contraction through VDCC-mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+, is paralleled by a conceptually similar mechanism that links depolarization-induced increases in [Ca2+]i to activation of Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors. This process, which has been termed excitation-transcription coupling, translates short-term Ca2+-signaling and contractile events into long-term regulation of the smooth muscle cell transcriptome. Unlike cardiac and skeletal muscle cells, smooth muscle cells are highly plastic; their phenotype is maintained through dynamic regulation of gene expression in response to environmental cues (Owens 1995). Thus, excitation-transcription coupling serves to maintain the contractile phenotype by promoting the expression of smooth muscle-specific genes. It also provides a mechanism for phenotypic switching to a “synthetic” phenotype characterized by expression of genes that promote proliferation, matrix deposition, and other functions that come into play under pathological conditions and in the context of vessel repair and new vessel formation. Recent work from Owens and colleagues (Wamhoff et al. 2004) has shown that VDCC-mediated elevations in Ca2+ act through two distinct mechanisms to regulate the contractile and synthetic/proliferative phenotypes. In the first, depolarization-induced Ca2+ elevation induces SRF (serum response factor)-regulated smooth muscle–specific genes (e.g., myosin heavy chain, smooth muscle α-actin) through activation of Rho/Rho kinase and stimulation of myocardin, a potent coactivator of SRF first identified by Olson and colleagues (Wang et al. 2001a). In the second mechanism, elevated intracellular Ca2+ acts through calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) to activate CREB (cAMP responsive element binding protein) and the immediately early gene, c-fos, which is involved in proliferative responses. A similar CaMK/CREB-dependent mechanism has been implicated in the VDCC-mediated induction of Egr-1 (Pulver-Kaste et al. 2006) and c-fos (Cartin et al. 2000) in native cerebral arteries, and TRP channels in gall bladder smooth muscle (Morales et al. 2007). In this latter study, a role for the phosphatase calcineurin was also suggested.

Spatially and Temporally Modulated Ca2+ Signals

Studies on the effects of Ca2+ signal modulation on transcription factor activation in smooth muscle cells are limited, but seminal work by Lewis and Tsien and colleagues (Dolmetsch et al. 1998; Li et al. 1998) in nonexcitable cells has shown a role for amplitude and frequency modulation of Ca2+ signals in differentially regulating the activity of Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors. These researchers showed that large transient increases in [Ca2+]i are sufficient to robustly activate NF-κB and c-Jun terminal kinase (JNK) but not NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells), which is effectively activated by a sustained, graded increase in global intracellular Ca2+. It has been further shown that activation of Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors is modulated by oscillatory elevations in intracellular Ca2+: for all transcription factors tested (NFAT, Oct/OAP, and NF-κB), high-frequency oscillations enhanced the efficacy of a given increase in Ca2+, whereas low-frequency oscillations activated only NF-κB.

Ca2+-Signaling Microdomains

Recent studies by Santana and coworkers suggest a model in which the scaffolding protein AKAP250 targets PKC and calcineurin to caveolin-containing membrane microdomains, where they associated with VDCCs to form a signaling unit capable of mediating persistent Ca2+ sparklets (Santana and Navedo 2009). These studies further indicate that persistent VDCC-mediated Ca2+ sparklets activate the Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent transcription factor NFATc3 (Nieves-Cintron et al. 2008), which modulates expression of the Kv2.1 voltage-dependent K+ channel and the β1 subunit of the BKCa channel in these cells (Amberg et al. 2004). By extension, similar complexes of P2X1Rs with kinases and phosphatases might form Ca2+-signaling microdomains in postjunctional smooth muscle cell membranes, enabling nerve-evoked purinergic transients to regulate activation of NFAT or other Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors.

CONCLUSIONS

In addition to global elevations in intracellular Ca2+ mediated by VDCCs, smooth muscle shows a variety of local Ca2+ signals, including Ca2+ sparks (RyRs), Ca2+ puffs (IP3Rs), Ca2+ waves (IP3Rs/RyRs), junctional Ca2+ transients (P2X1Rs), Ca2+ flashes (VDCCs), and Ca2+ sparklets (VDCCs). Each signal represents the manifestation of different molecular circuits, which collectively serve to modulate membrane potential, contractility, and gene expression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by NIH grants R37DK 053832, RO1 DK065947, RO1 HL44455, PO1 HL077378, P20 R016435, and RO1 HL098243; the Totman Trust for Medical Research; Research into Ageing (P332); The Royal Society (RG080197); and the British Heart Foundation (PG/07/115).

Footnotes

Editors: Martin Bootman, Michael J. Berridge, James W. Putney, and H. Llewelyn Roderick

Additional Perspectives on Calcium Signaling available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Amberg GC, Rossow CF, Navedo MF, Santana LF 2004. NFATc3 regulates Kv2.1 expression in arterial smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 279: 47326–47334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelotti T, Hofmann F 1996. Tissue-specific expression of splice variants of the mouse voltage-gated calcium channel α2δ subunit. FEBS Lett 397: 331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschrafi A, Sadtler S, Niculescu C, Rettinger J, Schmalzing G 2004. Trimeric architecture of homomeric P2X2 and heteromeric P2X1+2 receptor subtypes. J Mol Biol 342: 333–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayguinov O, Hagen B, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Sanders KM 2000. Intracellular calcium events activated by ATP in murine colonic myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C126–C135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Bolton TB 1986. Spontaneous transient outward currents in single visceral and vascular smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. J Physiol 381: 385–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Tsien RW 1987. A novel receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable channel activated by ATP in smooth muscle. Nature 328: 275–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ 1997. Elementary and global aspects of calcium signalling. J Physiol 499: 291–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K 1999. Molecular diversity of voltage-sensitive calcium channels in smooth muscle cells. J Lab Clin Med 133: 469–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaumer L, Qin N, Olcese R, Tareilus E, Platano D, Costantin J, Stefani E 1998. Structures and functions of calcium channel β subunits. J Bioenerg Biomembr 30: 357–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boittin FX, Macrez N, Halet G, Mironneau J 1999. Norepinephrine-induced Ca2+ waves depend on InsP(3) and ryanodine receptor activation in vascular myocytes. Am J Physiol 277: C139–C151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boittin FX, Coussin F, Morel JL, Halet G, Macrez N, Mironneau J 2000. Ca2+ signals mediated by Ins(1,4,5)P(3)-gated channels in rat ureteric myocytes. Biochem J 349: 323–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonev AD, Jaggar JH, Rubart M, Nelson MT 1997. Activators of protein kinase C decrease Ca2+ spark frequency in smooth muscle cells from cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol 273: C2090–C2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Berridge MJ 1996. Subcellular Ca2+ signals underlying waves and graded responses in HeLa cells. Curr Biol 6: 855–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley JE, Anderson UA, Woolsey SM, Thornbury KD, McHale NG, Hollywood MA 2004. Characterization of T-type calcium current and its contribution to electrical activity in rabbit urethra. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C1078–C1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain KL, Jackson VM, Trout SJ, Cunnane TC 2002. Intermittent ATP release from nerve terminals elicits focal smooth muscle Ca2+ transients in mouse vas deferens. J Physiol 541: 849–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain KL, Cuprian AM, Williams DJ, Cunnane TC 2003. The sources and sequestration of Ca2+ contributing to neuroeffector Ca2+ transients in the mouse vas deferens. J Physiol 553: 627–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdyga T, Wray S 2005. Action potential refractory period in ureter smooth muscle is set by Ca sparks and BK channels. Nature 436: 559–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ 1995. The control of calcium release in heart muscle. Science 268: 1045–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartin L, Lounsbury KM, Nelson MT 2000. Coupling of Ca2+ to CREB activation and gene expression in intact cerebral arteries from mouse: Roles of ryanodine receptors and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Circ Res 86: 760–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA 2000. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16: 521–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ 2008. Calcium sparks. Physiol Rev 88: 1491–1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB 1993. Calcium sparks: Elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science 262: 740–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier ML, Ji G, Wang Y, Kotlikoff MI 2000. Calcium-induced calcium release in smooth muscle: Loose coupling between the action potential and calcium release. J Gen Physiol 115: 653–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis BM, Catterall WA 1984. Purification of the calcium antagonist receptor of the voltage-sensitive calcium channel from skeletal muscle transverse tubules. Biochemistry 23: 2113–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuro A, Parker I 2004. Imaging the activity and localization of single voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J 86: 3250–3259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Xu K, Lewis RS 1998. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression [see comments]. Nature 392: 933–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essin K, Gollasch M 2009. Role of ryanodine receptor subtypes in initiation and formation of calcium sparks in arterial smooth muscle: Comparison with striated muscle. J Biomed Biotechnol 2009: 135249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A 2006. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441: 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foskett JK, White C, Cheung KH, Mak DO 2007. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol Rev 87: 593–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachini FR, Chiao CW, Carneiro FS, Lima VV, Carneiro ZN, Dorrance AM, Tostes RC, Webb RC 2009. Increased activation of stromal interaction molecule-1/Orai-1 in aorta from hypertensive rats: A novel insight into vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 53: 409–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachini FR, Webb RC, Tostes RC 2010. STIM and Orai proteins: Players in sexual differences in hypertension-associated vascular dysfunction? Clin Sci (Lond) 118: 391–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordienko DV, Bolton TB 2002. Crosstalk between ryanodine receptors and IP(3) receptors as a factor shaping spontaneous Ca2+-release events in rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol 542: 743–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordienko DV, Bolton TB, Cannell MB 1998. Variability in spontaneous subcellular calcium release in guinea-pig ileum smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 507: 707–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson TH, Haddock RE, Murray TP, Wojcikiewicz RJ, Hill CE 2004. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor subtypes are differentially distributed between smooth muscle and endothelial layers of rat arteries. Cell Calcium 36: 447–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Santana LF, Nelson MT 2002. Alkaline pH shifts Ca2+ sparks to Ca2+ waves in smooth muscle cells of pressurized cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H2169–H2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT 2005. Elementary purinergic Ca2+ transients evoked by nerve stimulation in rat urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol 564: 201–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner TJ, Werner ME, Nausch B, Vial C, Evans RJ, Nelson MT 2009. Nerve-evoked purinergic signalling suppresses action potentials, Ca2+ flashes and contractility evoked by muscarinic receptor activation in mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol 587: 5275–5288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT 2001. Voltage dependence of the coupling of Ca2+ sparks to BK(Ca) channels in urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C481–C490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Nelson MT 2002. Differential regulation of SK and BK channels by Ca2+ signals from Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in guinea-pig urinary bladder myocytes. J Physiol 541: 483–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Eubanks DC, Werner ME, Nelson MT 2010. Local elementary purinergic-induced Ca2+ transients: From optical mapping of nerve activity to local Ca2+ signaling networks. J Gen Physiol 136: 149–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Kadowaki S, Tanabe M, Takeshima H, Iino M 1999. Spatiotemporal dynamics of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate that underlies complex Ca2+ mobilization patterns. Science 284: 1527–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RC, Wang Q, Helliwell RM, Large WA 1993. Properties of spontaneous inward currents in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch 425: 233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosey MM, Barhanin J, Schmid A, Vandaele S, Ptasienski J, O’Callahan C, Cooper C, Lazdunski M 1987. Photoaffinity labelling and phosphorylation of a 165 kilodalton peptide associated with dihydropyridine and phenylalkylamine-sensitive calcium channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 147: 1137–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hullin R, Singer-Lahat D, Freichel M, Biel M, Dascal N, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V 1992. Calcium channel β subunit heterogeneity: Functional expression of cloned cDNA from heart, aorta and brain. EMBO J 11: 885–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino M, Kasai H, Yamazawa T 1994. Visualization of neural control of intracellular Ca2+ concentration in single vascular smooth muscle cells in situ. EMBO J 13: 5026–5031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Nelson MT 2000. Differential regulation of Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves by UTP in rat cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1528–C1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Stevenson AS, Nelson MT 1998a. Voltage dependence of Ca2+ sparks in intact cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol 274: C1755–C1761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Wellman GC, Heppner TJ, Porter VA, Perez GJ, Gollasch M, Kleppisch T, Rubart M, Stevenson AS, Lederer WJ, et al. 1998b. Ca2+ channels, ryanodine receptors and Ca2+-activated K+ channels: A functional unit for regulating arterial tone. Acta Physiol Scand 164: 577–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Porter VA, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT 2000. Calcium sparks in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C235–C256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkat-Rott K, Lehmann-Horn F 2004. The impact of splice isoforms on voltage-gated calcium channel α1 subunits. J Physiol 554: 609–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai Y, Yamazawa T, Sakurai T, Taketani Y, Iino M 1997. Endothelium-dependent frequency modulation of Ca2+ signalling in individual vascular smooth muscle cells of the rat. J Physiol 504: 349–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keef KD, Hume JR, Zhong J 2001. Regulation of cardiac and smooth muscle Ca2+ channels (CaV1.2a,b) by protein kinases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1743–C1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS 2001. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors and ATP signalling at synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MG, Cheng H, Santana LF, Jiang YH, Lederer WJ, Schneider MF 1996. Two mechanisms of quantized calcium release in skeletal muscle. Nature 379: 455–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockner U, Isenberg G 1985. Action potentials and net membrane currents of isolated smooth muscle cells (urinary bladder of the guinea-pig). Pflugers Arch 405: 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ, Nelson MT 1998. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol 508: 199–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo IY, Wolfle SE, Hill CE 2010. T-type calcium channels and vascular function: The new kid on the block? J Physiol 589: 783–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C, Wier WG 2002. Evoked and spontaneous purinergic junctional Ca2+ transients (jCaTs) in rat small arteries. Circ Res 91: 454–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C, Vial C, Evans RJ, Wier WG 2006. P2X1 receptors mediate sympathetic postjunctional Ca2+ transients in mesenteric small arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H3106–3113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL 2010. Ryanodine receptors: Structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Poburko D, Kuo KH, Seow CY, van Breemen C 2002. Ca2+ oscillations, gradients, and homeostasis in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1571–H1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AT, Imagawa T, Campbell KP 1987. Structural characterization of the 1,4-dihydropyridine receptor of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel from rabbit skeletal muscle. Evidence for two distinct high molecular weight subunits. J Biol Chem 262: 7943–7946 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Llopis J, Whitney M, Zlokarnik G, Tsien RY 1998. Cell-permeant caged InsP3 ester shows that Ca2+ spike frequency can optimize gene expression [see comments]. Nature 392: 936–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE Jr, Meyer T 2005. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol 15: 1235–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lopez JR, Shacklock PS, Balke CW, Wier WG 1995. Local calcium transients triggered by single L-type calcium channel currents in cardiac cells. Science 268: 1042–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravall M, Mainen ZF, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K 2000. Estimating intracellular calcium concentrations and buffering without wavelength ratioing. Biophys J 78: 2655–2667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miriel VA, Mauban JR, Blaustein MP, Wier WG 1999. Local and cellular Ca2+ transients in smooth muscle of pressurized rat resistance arteries during myogenic and agonist stimulation. J Physiol 518 (Pt 3): 815–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironneau J, Arnaudeau S, Macrez-Lepretre N, Boittin FX 1996. Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves activate different Ca2+-dependent ion channels in single myocytes from rat portal vein. Cell Calcium 20: 153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Isotani E, Huang J, Ding H, Stull JT, Kamm KE 2008. Myosin light chain kinase activation and calcium sensitization in smooth muscle in vivo. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C358–C364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Schulla V, Welling A, Feil R, Feil S, Wegener JW, Hofmann F, Klugbauer N 2003. Dominant role of smooth muscle L-type calcium channel Cav1.2 for blood pressure regulation. EMBO J 22: 6027–6034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Diez A, Puyet A, Camello PJ, Camello-Almaraz C, Bautista JM, Pozo MJ 2007. Calcium controls smooth muscle TRPC gene transcription via the CaMK/calcineurin-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C553–C563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufti RE, Brett SE, Tran CH, Abd El-Rahman R, Anfinogenova Y, El-Yazbi A, Cole WC, Jones PP, Chen SR, Welsh DG 2010. Intravascular pressure augments cerebral arterial constriction by inducing voltage-insensitive Ca2+ waves. J Physiol 588: 3983–4005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulryan K, Gitterman DP, Lewis CJ, Vial C, Leckie BJ, Cobb AL, Brown JE, Conley EC, Buell G, Pritchard CA, et al. 2000. Reduced vas deferens contraction and male infertility in mice lacking P2X1 receptors. Nature 403: 86–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Yamamura H, Suzuki T, Kang MG, Ohya S, Murakami A, Miyoshi I, Sasano H, Muraki K, Hano T, et al. 2003. Modified cardiovascular L-type channels in mice lacking the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel β3 subunit. J Biol Chem 278: 43261–43267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Votaw VS, Santana LF 2005. Constitutively active L-type Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 11112–11117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB 1990. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol 259: C3–C18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ 1995. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks [see comments]. Science 270: 633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton CL, Mignery GA, Sudhof TC 1994. Co-expression in vertebrate tissues and cell lines of multiple inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptors with distinct affinities for InsP3. J Biol Chem 269: 28613–28619 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neylon CB, Richards SM, Larsen MA, Agrotis A, Bobik A 1995. Multiple types of ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels are expressed in vascular smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 215: 814–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng LC, Ramduny D, Airey JA, Singer CA, Keller PS, Shen XM, Tian H, Valencik M, Hume JR 2010. Orai1 interacts with STIM1 and mediates capacitative Ca2+ entry in mouse pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C1079–C1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieves-Cintron M, Amberg GC, Navedo MF, Molkentin JD, Santana LF 2008. The control of Ca2+ influx and NFATc3 signaling in arterial smooth muscle during hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 15623–15628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitina E, Zhang ZD, Kawashima A, Jahromi BS, Bouryi VA, Takahashi M, Xie A, Macdonald RL 2007. Voltage-dependent calcium channels of dog basilar artery. J Physiol 580: 523–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA 2002. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev 82: 1013–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens GK 1995. Regulation of differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Physiol Rev 75: 487–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Hopson K, Truelove J, Chun J, Wang Y, Waeber C 2011. S1P activates Store-operated calcium entry via receptor and non receptor-mediated pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: 919–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP 2006. A key role for STIM1 in store operated calcium channel activation in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res 7: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP 2008. ORAI and store-operated calcium influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38: 744–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Matchkov V, Ivarsen A, Aalkjaer C, Nilsson H 2001. Hypothesis for the initiation of vasomotion. Circ Res 88: 810–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Patlak JB, Nelson MT 1999. Functional coupling of ryanodine receptors to KCa channels in smooth muscle cells from rat cerebral arteries. J Gen Physiol 113: 229–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT 2001. Micromolar Ca2+ from sparks activates Ca2+-sensitive K+channels in rat cerebral artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1769–C1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E 2003. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev 83: 117–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo MJ, Perez GJ, Nelson MT, Mawe GM 2002. Ca2+ sparks and BK currents in gallbladder myocytes: Role in CCK-induced response. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G165–G174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzan T, Rizzuto R, Volpe P, Meldolesi J 1994. Molecular and cellular physiology of intracellular calcium stores. Physiol Rev 74: 595–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz G, Diener M 2008. Characterization of ryanodine receptors in rat colonic epithelium. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 193: 151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulver-Kaste RA, Barlow CA, Bond J, Watson A, Penar PL, Tranmer B, Lounsbury KM 2006. Ca2+ source-dependent transcription of CRE-containing genes in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H 1983. Calcium channel modulation by neurotransmitters, enzymes and drugs. Nature 301: 569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, et al. 2005. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 169: 435–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruehlmann DO, Lee CH, Poburko D, van Breemen C 2000. Asynchronous Ca2+ waves in intact venous smooth muscle. Circ Res 86: E72–E79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders KM 2001. Invited review: Mechanisms of calcium handling in smooth muscles. J Appl Physiol 91: 1438–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana LF, Navedo MF 2009. Molecular and biophysical mechanisms of Ca2+ sparklets in smooth muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 47: 436–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana LF, Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Nieves-Cintron M, Votaw VS, Ufret-Vincenty CA 2008. Calcium sparklets in arterial smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35: 1121–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider P, Hopp HH, Isenberg G 1991. Ca2+ influx through ATP-gated channels increments [Ca2+]i and inactivates ICa in myocytes from guinea-pig urinary bladder. J Physiol 440: 479–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieck GC, Kannan MS, Prakash YS 1997. Heterogeneity in dynamic regulation of intracellular calcium in airway smooth muscle cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 75: 878–888 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snutch TP, Sutton KG, Zamponi GW 2001. Voltage-dependent calcium channels—Beyond dihydropyridine antagonists. Curr Opin Pharmacol 1: 11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV 2003. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: Modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev 83: 1325–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RJ, Weinert JS, Publicover NG 1999. Visualization of origins and propagation of excitation in canine gastric smooth muscle. Am J Physiol 277: C448–C460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull JT, Lin PJ, Krueger JK, Trewhella J, Zhi G 1998. Myosin light chain kinase: Functional domains and structural motifs. Acta Physiol Scand 164: 471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Watanabe H, Murakami M, Ono K, Munehisa Y, Koyama T, Nobori K, Iijima T, Ito H 2007. Functional role of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 361: 934–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasker PN, Michelangeli F, Nixon GF 1999. Expression and distribution of the type 1 and type 3 inositol 1,4, 5-trisphosphate receptor in developing vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res 84: 536–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Lipp P, Berridge MJ, Bootman MD 1998. Hormone-evoked elementary Ca2+ signals are not stereotypic, but reflect activation of different size channel clusters and variable recruitment of channels within a cluster. J Biol Chem 273: 27130–27136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY 1980. New calcium indicators and buffers with high selectivity against magnesium and protons: Design, synthesis, and properties of prototype structures. Biochemistry 19: 2396–2404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaghy PL, Williams JS, Schwartz A 1987. Receptor pharmacology of calcium entry blocking agents. Am J Cardiol 59: 9A–17A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaithianathan T, Narayanan D, Asuncion-Chin MT, Jeyakumar LH, Liu J, Fleischer S, Jaggar JH, Dopico AM 2010. Subtype identification and functional characterization of ryanodine receptors in rat cerebral artery myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C264–C278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnai P, Hunyady L, Balla T 2009. STIM and Orai: The long-awaited constituents of store-operated calcium entry. Trends Pharmacol Sci 30: 118–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vial C, Evans RJ 2002. P2X(1) receptor-deficient mice establish the native P2X receptor and a P2Y6-like receptor in arteries. Mol Pharmacol 62: 1438–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, et al. 2006. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312: 1220–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamhoff BR, Bowles DK, McDonald OG, Sinha S, Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV, Owens GK 2004. L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels modulate expression of smooth muscle differentiation marker genes via a rho kinase/myocardin/SRF-dependent mechanism. Circ Res 95: 406–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Chang PS, Wang Z, Sutherland L, Richardson JA, Small E, Krieg PA, Olson EN 2001a. Activation of cardiac gene expression by myocardin, a transcriptional cofactor for serum response factor. Cell 105: 851–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SQ, Song LS, Lakatta EG, Cheng H 2001b. Ca2+ signalling between single L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in heart cells. Nature 410: 592–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Deng X, Hewavitharana T, Soboloff J, Gill DL 2008. Stim, ORAI and TRPC channels in the control of calcium entry signals in smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35: 1127–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Deng X, Mancarella S, Hendron E, Eguchi S, Soboloff J, Tang XD, Gill DL 2010. The calcium store sensor, STIM1, reciprocally controls Orai and CaV1.2 channels. Science 330: 105–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener JW, Schulla V, Lee TS, Koller A, Feil S, Feil R, Kleppisch T, Klugbauer N, Moosmang S, Welling A, et al. 2004. An essential role of Cav1.2 L-type calcium channel for urinary bladder function. FASEB J 18: 1159–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman GC, Nelson MT 2003. Signaling between SR and plasmalemma in smooth muscle: Sparks and the activation of Ca2+-sensitive ion channels. Cell Calcium 34: 211–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XR, Lin MJ, Yip KP, Jeyakumar LH, Fleischer S, Leung GP, Sham JS 2005. Multiple ryanodine receptor subtypes and heterogeneous ryanodine receptor-gated Ca2+ stores in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289: L338–L348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]