Abstract

Purpose

Brushite crystallization might be important in stone formation and prevention. To explore this question new methods for the saturation and crystal growth of brushite were devised that are applicable to whole urine without any computer program.

Materials and Methods

The saturation value (concentration-to-product ratio) was determined by dividing the molar concentration product of Ca ([Ca]) and phosphate ([P]), that is [Ca] × [P], of original urine by the steady state solubility obtained after incubating with an excess of brushite (10 mg/ml) for 5 hours. Crystal growth was measured from the depletion of filtrate ([Ca] × [P]) 3 hours after seeding with brushite (0.25 mg/ml). To test the effect of pH, Ca and citrate the saturation value and crystal growth were determined in 24-hour urine samples from 4 normal volunteers and 2 stone formers, and modified artificially to produce 4 ranges of pH, Ca and citrate by adding acid, base, Ca or citrate.

Results

The saturation value and crystal growth of brushite increased with an increase in pH or the Ca concentration but they decreased when the citrate concentration increased. The saturation value correlated strongly with crystal growth.

Conclusions

The new methods of brushite saturation value and crystal growth should help discern how abnormalities in urinary pH, Ca and citrate interact to influence the formation of Ca stones in cases of distal renal tubular acidosis and alkali therapy.

Keywords: kidney calculi, urine, brushite, crystallization, calcium

The importance of brushite (CaHPO4 · 2H2O) in kidney stone formation and prevention has been emphasized by 3 recent developments. In their detailed examination of renal papillae in 2003 Evan et al reported that Ca oxalate stones in idiopathic Ca stone formers originate from plaques composed of Ca phosphate in the basement membrane of the thin loop of Henle.1 In 2004 Parks et al found that the Ca phosphate fraction in stones had dramatically increased during the last 3 decades, coincidentally with an increase in urinary pH and brushite saturation.2 In 2006 Rodgers et al introduced the new computer program JESS for estimating the urinary saturation of stone forming salts.3 This program recognized additional complexes, eg Ca phosphocitrate, which were not included in the widely used EQUIL 2 program.4 Thus, compared with EQUIL 2, JESS revealed a less pronounced increase in brushite saturation when pH was increased.

These studies indicate that Ca phosphate may not only serve as a nidus of Ca oxalate stones,1,5 but it is also becoming a prominent component of stones.2 Thus, determining the saturation and inhibitor activity of brushite in whole urine may be helpful for gauging the formation of Ca oxalate and Ca phosphate stones. In support, urinary supersaturation has been shown to be associated with stone composition.6

Unfortunately current methods for estimating brushite saturation and inhibitor activity in whole urine are deficient due to the intrinsic complexity of urine, which has many unidentified substances and inhibitors. When estimating urinary saturation, computer programs have limitations due to unknown or incorrect complexes.3 The semi-empirical method that we introduced previously (the activity product ratio)7 obviates the need to calculate complexes. However, it is cumbersome, requiring 2 days of urine incubation with brushite. To assess inhibitor activity we had devised a method for the crystal growth of brushite in whole urine8 but it was too laborious and time-consuming to be adopted.

The current study was performed to develop simple and reliable techniques for estimating brushite urinary saturation and crystal growth that are applicable to whole urine. Designed for completion within a working day, these methods were tested in multiple urine samples, in which urinary pH, Ca and citrate were artificially altered to simulate clinical or physiological conditions known to be associated with Ca phosphate stones, including distal renal tubular acidosis,9 acquired metabolic acidosis of topiramate treatment10 and alkali therapy.11

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Data and Urine Samples

Crystallization studies were performed in 24-hour urine samples collected from 6 healthy adult subjects, including 3 men and 3 women, as well as from 3 men and 3 women with kidney stones containing Ca. Urine samples were kept under refrigeration or in an ice chest without any preservative during collection. Six urine samples from 3 healthy subjects and 3 stone formers, respectively, were used to determine the time points for evaluating brushite CPR, CG or CD. To assess the effect of varying pH, Ca and citrate on CPR and CG 6 sets of urine samples were examined from 4 healthy subjects and 2 stone formers, respectively. Ca acid phosphate is believed to be a precursor phase of hydroxyapatite, justifying the examination of brushite.

Preparation of Whole Urine

Soon after completing the 24-hour urine collection a fresh aliquot of whole urine was centrifuged to remove cellular debris and crystals. The supernatant was then filtered through a 0.22 μ filter to eliminate any remaining crystalline material

CPR of Brushite

The method of determining brushite CPR was simplified from the method reported previously.7 To 5 to 10 ml urine filtrate a drop of formaldehyde to prevent bacterial contamination and an excess of brushite (5 mg/ml) were added. The brushite preparation used in the experiments was composed of aged crystals of uniform size and appearance (Mallinckrodt, St. Louis, Missouri). After 5 hours of incubation under constant stirring with a magnetic bar at 37C while pH was kept constant at the designated pH by titration with dilute 0.1 N hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide 2 ml suspension were filtered through a 0.22 μ filter. The filtrates before and after incubation with brushite were analyzed for Ca and phosphorus, permitting the calculation of the molar concentration product or [Ca] × [P]. The ratio of initial [Ca] × [P] divided by the final [Ca] × [P] after incubation with an excess of brushite yielded CPR, for which a value of 1 indicated saturation, greater than 1 indicated supersaturation and less than 1 indicated under saturation. Selection of the amount of brushite and the incubation duration (5 mg brushite per ml for 5 hours) was based on the hourly change in [Ca] × [P], as described.

CG or CD of Brushite

To 5 to 10 ml urine filtrate a drop of formaldehyde and a small amount of brushite (0.25 mg/ml) were added. After 3 hours of incubation under constant stirring with a magnetic bar at 37C and constant pH 2 ml of suspension were filtered and the resulting filtrate was analyzed for Ca and phosphorus. A decrement in [Ca] × [P] after seeding with brushite yielded CG, while an increment in [Ca] × [P] represented CD. The decision to incubate 0.25 mg brushite per ml urine for 3 hours was made according to the time course of the change in [Ca] × [P], as described.

Assessing the Effects of pH, Ca and Citrate

To assess the effect of varying pH on brushite CPR and CG or CD the pH of the urine filtrate from each of 6 urine samples was adjusted to 5.65, 6.0, 6.35 and 6.7 by titration with 0.1 N hydrochloric acid or 0.1 N sodium hydroxide. The Ca and citrate contents were unchanged. To assess the effect of varying Ca the Ca concentration of the urine filtrate from each of 6 urine samples was adjusted to a final value of 2.5 mmol (100 mg)/l, 3.75 mmol (150 mg)/l, 5 mmol (200 mg)/l and 6.25 mmol (250 mg)/l. To do so the Ca concentration of the original urine filtrate was rapidly determined and the 4 designated Ca concentrations were then attained by dilution with distilled water or by the addition of Ca chloride. Urinary pH and citrate concentrations were kept the same.

To assess the effect of varying citrate, varying amounts of citrate (0, 1, 2 and 3 mmol/l, respectively, as potassium citrate) were added to the urine filtrate. Because of the delay in citrate analysis, the original citrate concentration was not available soon enough to permit adjusting citrate concentrations to the same predetermined levels. The Ca concentration and pH were unchanged

Analytical and Statistical Methods

Urinary Ca, phosphorus and citrate were analyzed by previously described methods.12 The significance of associations between various parameters was assessed by regression analysis.

RESULTS

Time Course of [Ca] × [P] After Incubation With Brushite

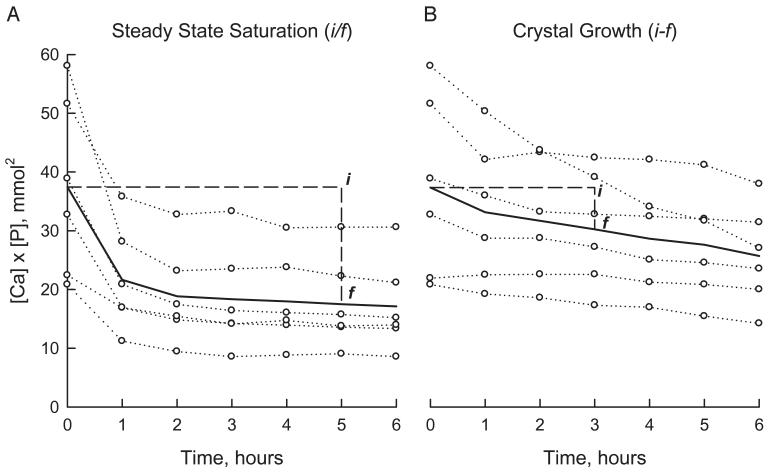

Figure 1 shows the change in [Ca] × [P] more than 6 hours after incubation with brushite. After adding an excess of brushite (5 mg/ml) [Ca] × [P] of the filtrate decreased rapidly, reaching a steady state value at about 4 hours (fig. 1, A). The value at 5 hours was not significantly altered by the further addition of brushite or additional incubation time (data not shown). The original [Ca] × [P] divided by the value at 5 hours yielded CPR, a measure of urinary saturation with respect to brushite.

Fig. 1.

Time course of change in filtrate [Ca] × [P] after adding excess brushite (A) and seeding with brushite (B). Circles connected by dotted lines indicate data on separate urine samples. Solid lines represent mean. i, initial [Ca] × [P]. f, final [Ca] × [P] after incubation with brushite.

After seeding with a small amount of brushite (0.25 mg/ml) the filtrate [Ca] × [P] decreased slowly during 6 hours (fig. 1, B). The value at 3 hours was higher than the value at 6 hours and much greater than the steady state value 6 hours after incubation with an excess of brushite. In few samples the filtrate [Ca] × [P] increased after adding brushite and CPR was less than 1, indicative of CD (data not shown).

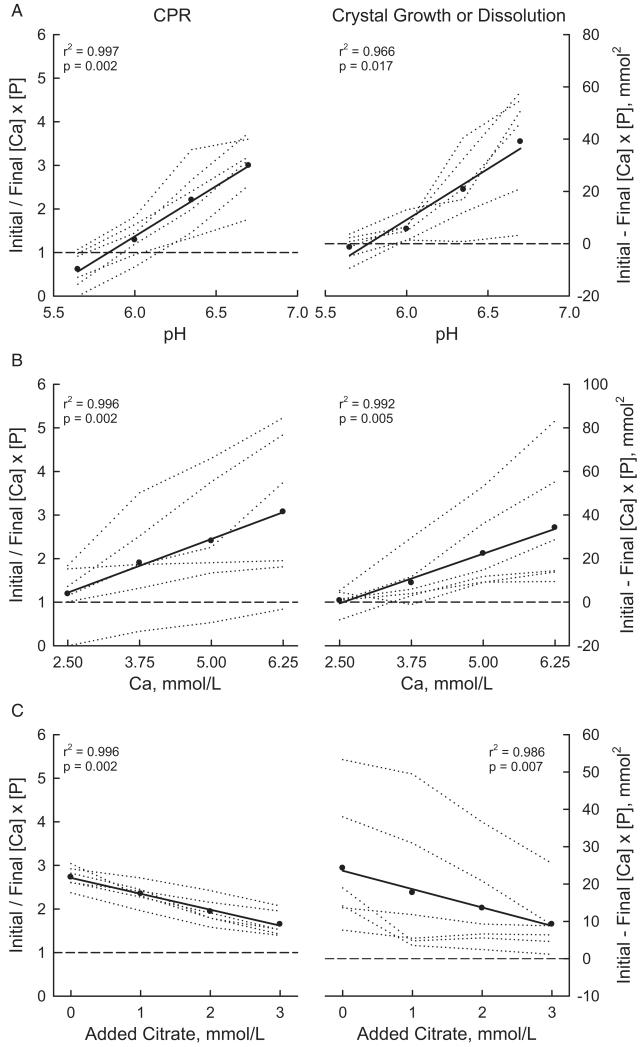

Effect of Varying pH on CPR and CG

At a pH of 5.65 some samples were under saturated with a CPR of less than 1 (fig. 2, A). With increasing pH CPR increased progressively (r2 = 0.997, p = 0.002). The mean interpolated value of CPR at 6.0 was 1.2 lower than the value at pH 6.5. With increasing pH all samples showed progressively increasing CG (r2 = 0.966, p = 0.017). Mean CG increased by 19.5 mmol2 with a change in pH from 6 to 6.5.

Fig. 2.

Dependence of CPR and CG on urinary pH (A), and urinary Ca (B) and citrate (C) concentrations. CPR = initial/final [Ca] × [P]. CG = initial – final [Ca] × [P]. Dotted lines indicate values in separate urine samples. Circles represent mean. Diagonal lines represent regression. Horizontal dashed line indicates saturation value (CPR 1) or zero crystal growth.

Effect of Varying Ca Concentration on CPR and CG

With increasing Ca concentrations brushite CPR increased progressively (r2 = 0.996, p = 0.002, fig. 2, B). Mean CPR increased by 1.2 when the Ca concentration was increased from 2.5 to 5.0 mmol/l. Similarly CG increased progressively with an increase in Ca concentration (r2 = 0.992, p = 0.005). Mean CG increased by 22.8 mmol2 when the Ca concentration was increased by 2.5 mmol (100 mg)/l from 2.5 to 5 mmol/l.

Effect of Varying Concentration of Added Citrate

When increasing amounts of citrate were added, brushite CPR and CG progressively decreased (r2 = 0.996 and 0.992, p = 0.002 and 0.005, respectively, fig. 2, C). When the added citrate concentration was increased from 0 to 2 mmol/l, mean CPR decreased by 0.7 and mean CG decreased by 9.8 mmol.2

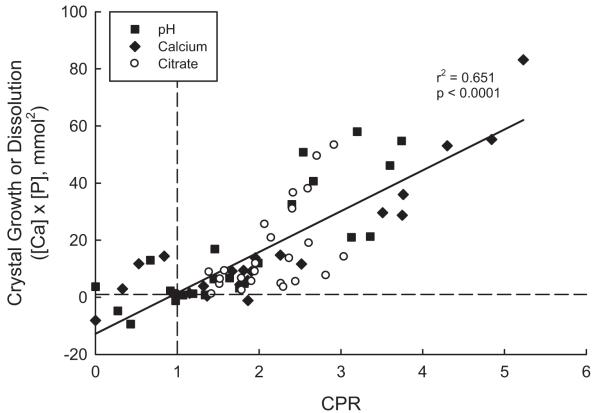

Dependence of CG on Brushite CPR

In all 72 experiments, that is 6 urine samples each of 4 ranges of pH, Ca and citrate, the brushite CG or CD directly correlated with the corresponding CPR (r2 = 0.651, p <0.0001, fig. 3). Values in experiments merged with those derived from Ca and citrate experiments.

Fig. 3.

Dependence of CG or CD of brushite on CPR. Squares represent values in experiments with pH variation. Diamonds represent values in experiments with Ca variation. Circles represent values in experiments with citrate variation. Diagonal line represents regression line. Dashed horizontal line indicates zero crystal growth. Dashed vertical line at CPR 1 indicates saturation value. Points at CG less than 1 and CPR less than 1 represent under saturated samples with crystal dissolution.

DISCUSSION

The intrinsic complexity of urine has hampered the development of reliable methods of assessing Ca phosphate crystallization. Therefore, we developed new methods to assess the saturation and crystal growth of brushite that are applicable to whole urine. Urinary saturation (CPR) was empirically determined after adding an excess of brushite and CG was determined after seeding with a small amount of brushite.

In artificial solutions containing known components urinary brushite saturation can be accurately calculated as the activity product of Ca2+ and since these ionic components can be estimated from known soluble complexes using computer programs. In synthetic medium a detailed analysis of brushite crystal growth is also possible.13

When computer based methods are applied to whole urine, they suffer from an incomplete or inaccurate estimation of soluble complexes. Whole urine is a complex solution containing many components that are not routinely measured and, thus, computer based methods probably overestimate urinary saturation.14 Even between available computer programs JESS yields data with different physiological implications than those of EQUIL 2 by acknowledging additional complexes.3 Some of the unmeasured urinary components probably have inhibitor activity against brushite crystallization. To our knowledge there is no satisfactory method to determine brushite CG in whole urine.

The new methods for CPR and CG do not rely on computer programs to calculate soluble complexes. They represent a refinement of our earlier semi-empirical methods7,8 based on the actual growth of added synthetic brushite. They were simplified to be completed within a working day. In our original description CPR was obtained by incubating 2 mg brushite per ml urine for 2 days.7 By adding more brushite (5 mg/ml) the duration of incubation was shortened to 5 hours. Previously CG was obtained by incubating 0.5 mg brushite per ml for 2 days.8 In the new method CG was achieved in 3 hours after seeding with a smaller amount of seed and expressed as the actual decrement in [Ca] × [P]. By shortening the incubation duration the new methods helped allay concern that some urinary components may undergo degradation during prolonged incubation at body temperature.

To assess the feasibility of CPR and CG we tested the effects of varying urinary pH, Ca and citrate, which are the 3 principal determinants of Ca phosphate crystallization, as encountered in distal renal tubular acidosis9 and acquired metabolic acidosis of topiramate therapy,10 and following alkali treatment for calcareous stones.11 In distal renal tubular acidosis or metabolic acidosis urinary pH and Ca are often increased and urinary citrate is low.9,10 While these disturbances should increase the urinary saturation of brushite, the degree of this increase depends on whether EQUIL 2 or JESS is used to estimate the urinary saturation.3 Following potassium citrate therapy the urinary saturation of brushite is determined by a balance of the tendency toward increased saturation from high urinary pH and the tendency toward decreased saturation from higher citrate and modestly lower Ca.11 Using EQUIL 2 varying effects of potassium citrate on brushite urinary saturation were found.11,15 JESS might reveal an attenuated increase in brushite urinary saturation.3

In this study we purposely created a wide variation in urinary pH, Ca and citrate separately in multiple whole urine samples by the appropriate addition of acid, base, Ca or citrate. In such manipulated urine samples brushite CPR increased with an increase in pH from the dissociation of phosphate and Ca from more highly ionized Ca, while it decreased with an increase in citrate from the complexation of Ca. CG showed similar directional changes with pH, Ca and citrate. CG was highly correlated with CPR, suggesting that the changes in brushite CG produced by these alterations in urinary composition may have resulted largely from decreased brushite saturation. From the separate effects of pH, Ca and citrate shown we fully anticipate that CPR and CG would reveal the combined effects of changes in these urinary components noted in actual clinical situations, such as renal tubular acidosis and alkali therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

The new method of determining brushite CPR in whole urine should help clarify concerns raised by the introduction of the JESS program.3 The application of brushite CPR and CG is warranted in conditions predisposing to Ca phosphate stones.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Janice Koska provided technical assistance and Dr. Prasanthi Tondapu obtained patient urine samples.

Supported by United States Public Health Service Grant P01-DK20543 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- [Ca]

Ca concentration product

- CD

crystal dissolution

- CG

crystal growth

- CPR

concentration-to-product ratio

- JESS

joint expert speciation system

- [P]

phosphate concentration product

REFERENCES

- 1.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, Parks JH, Bledsoe SB, Shao Y, et al. Randall’s plaque of patients with nephrolithiasis begins in basement membranes of thin ascending loops of Henle. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:607. doi: 10.1172/JCI17038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks JH, Worcester EM, Coe FL, Evan AP, Lingeman JE. Clinical implications of abundant calcium phosphate in routinely analyzed kidney stones. Kidney Int. 2004;66:777. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodgers A, Allie-Hamdulay S, Jackson G. Therapeutic action of citrate in urolithiasis explained by chemical speciation: increase in pH is the dominant factor. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:361. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werness PG, Brown CM, Smith LH, Finlayson B. EQUIL 2: a basic computer program for the calculation of urinary saturation. J Urol. 1985;134:1242. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47703-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pak CYC. Physicochemical basis for the formation of renal stones of calcium phosphate origin: calculation of the degree of saturation of urine with respect to brushite. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:1914. doi: 10.1172/JCI106158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asplin JR, Parks JH, Lingeman JE, Kahnoski R, Mardis H, Lacey S, et al. Supersaturation and stone composition in a network of dispersed treatment sites. J Urol. 1998;159:1821. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pak CYC, Holt K. Nucleation and growth of brushite and calcium oxalate in urine of stone-formers. Metabolism. 1976;25:665. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(76)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohata M, Pak CYC. The effect of diphosphonate on calcium phosphate crystallization in urine in vitro. Kidney Int. 1973;4:401. doi: 10.1038/ki.1973.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preminger GM, Sakhaee K, Skurla C, Pak CYC. Prevention of recurrent calcium stone formation with potassium citrate therapy in patients with distal renal tubular acidosis. J Urol. 1985;134:20. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)46963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welch BJ, Graybeard D, Moe OW, Maalouf NM, Sakhaee K. Biochemical and stone-risk profile with topiramate treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:555. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakhaee K, Nicar MJ, Hill K, Pak CYC. Contrasting effects of potassium citrate and sodium citrate therapies on urinary chemistries and crystallization of stone-forming salt. Kidney Int. 1983;24:348. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pak CYC, Skurla C, Harvey JA. Graphic display of urinary risk factors for renal stone formation. J Urol. 1985;134:867. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47496-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barone JP, Nancollas GH, Tomson M. The seeded growth of calcium phosphate: the kinetics of growth of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate on hydroxyapatite. Calc Tissue Res. 1976;21:171. doi: 10.1007/BF02547394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pak CYC, Hayashi Y, Finlayson B, Chu S. Estimation of the state of saturation of brushite and calcium oxalate in urine: a comparison of three methods. J Lab Clin Med. 1977;89:891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wabner CL, Pak CYC. Effect of orange juice consumption on urinary stone risk factors. J Urol. 1993;149:1405. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]