Abstract

Background

Nursing home residents with advanced dementia commonly experience burdensome and costly interventions (eg, tube feeding) that may be of limited clinical benefit. To our knowledge, Medicare expenditures have not been extensively described in this population.

Methods

Nursing home residents with advanced dementia in 22 facilities (N=323) were followed up for 18 months. Clinical and health services use data were collected every 90 days. Medicare expenditures were described. Multivariate analysis was used to identify factors associated with total 90-day expenditures for (1) all Medicare services and (2) all Medicare services excluding hospice.

Results

Over an 18-month period, total mean Medicare expenditures were $2303 per 90 days but were highly skewed; expenditures were less than $500 for 77.1% of the 90-day assessment periods and more than $12 000 for 5.5% of these periods. The largest proportion of Medicare expenditures were for hospitalizations (30.2%) and hospice (45.6%). Among decedents (n=177), mean Medicare expenditures increased by 65% in each of the last 4 quarters before death owing to an increase in both acute care and hospice. After multivariable adjustment, not living in a special care dementia unit was a modifiable factor associated with higher total expenditures for all Medicare services. Lack of a do-not-hospitalize order, tube feeding, and not living in a special care unit were associated with higher nonhospice Medicare expenditures.

Conclusions

Medicare expenditures among nursing home residents with advanced dementia vary substantially. Hospitalizations and hospice account for most spending. Strategies that promote high-quality palliative care may shift expenditures away from aggressive treatments for these patients at the end of life.

Dementia is a leading cause of death among older Americans.1 In 2000, 5 million adults in the United States had dementia, and projections predict 13 million by 2050.2 Health care expenditures for dementia are estimated to total $172 billion in 2010.2 These costs will rise as the number of persons living to experience the end stage of this disease increases.

Although 70% of persons with dementia die in nursing homes (NHs),3 most research describing health care spending for these individuals has been conducted in the community setting, and almost none has focused on end-stage disease. For Americans older than 65 years, Medicare covers the costs of acute care, subacute care, physician and other provider services, hospice, prescription drugs, and diagnostic tests. Medicare does not cover NH care, which is generally paid for by Medicaid after individuals exhaust their own resources. The total Medicare and Medicaid payments for patients with dementia are roughly 3 times higher than for age-matched controls.2,4 Total direct costs increase substantially over the course of the disease, with much of the increase in the later stages attributable to spending for NH care.5 Although per diem Medicaid payments account for most public spending within the NH setting, limited data suggest that Medicare expenditures explain most of the spending variation among dying residents with dementia.6 How this spending breaks down across the various Medicare services has not been well described.

Nursing home residents with advanced dementia commonly experience potentially burdensome and costly interventions (eg, hospital transfer, tube feeding) that may be of limited clinical benefit.7 Among patients with cancer, advance care planning has been shown to be associated with lower costs in the last week of life, and lower expenditures are associated with a higher-quality dying experience.8 We are not aware of prior research identifying factors that influence health care costs in end-stage dementia.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to describe and examine factors associated with Medicare expenditures in advanced dementia. We used data from a multisite cohort study that prospectively followed up 323 NH residents with advanced dementia for 18 months.7,9

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

The study included participants in the Choices, Attitudes, and Strategies for Care of Advanced Dementia at the End-of-Life (CASCADE) study,9 a prospective cohort study conducted between February 2003 and February 2009 that described the experience of NH residents with advanced dementia and their families. The detailed methods of this study are provided elsewhere.7,9

Residents were recruited from 22 NHs with more than 60 beds and within 60 miles of Boston, Massachusetts. Resident eligibility criteria included (1) age older than 60 years, (2) dementia (any type) (determined from medical record), and (3) Global Deterioration Scale score of 7 (ascertained by nurse interview).10 A Global Deterioration Scale score of 7 is characterized by profound memory deficits (unable to recognize family), limited verbal communication (<5 words), incontinence, and inability to ambulate. Residents had to have English-speaking health care proxies (HCPs) who provided informed consent for their participation and for the residents’ participation. The institutional review board of Hebrew SeniorLife Institute for Aging Research, Boston, approved the study’s conduct.

DATA COLLECTION

Resident assessments were conducted at baseline and quarterly for up to 18 months through chart reviews, nurse interviews, and clinical assessments. If the resident died, a chart review and a nurse interview were conducted within 14 days of death. Telephone interviews with HCPs were conducted at baseline and quarterly for up to 18 months.

USE OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES

Medicare health services used during the intervals between assessments were collected from residents’ charts. They included hospital admissions, emergency department (ED) visits, primary care provider visits in NH, and hospice enrollment. Hospitalization data included the admission date, length of stay, and reasons for admission (abstracted from the hospital discharge summary by research assistants). Emergency department data included dates of service and primary reason for the visit. Dates of enrollment into the Medicare hospice benefit and the number of physician and nurse practitioner visits (recorded separately) were also abstracted from the medical records.

The use of skilled nursing facility (SNF) services was not collected as part of the CASCADE study. Therefore, we identified all hospital admissions lasting at least 3 nights (required to qualify for an SNF stay). Senior NH administrators were contacted retrospectively to determine whether the resident received SNF care after hospitalization and, if so, the length of the SNF stay and the Resource Utilization Group codes used to bill Medicare.

HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURES

Expenditures for Medicare services were estimated using publically available sources and based on nationally representative rates from 2007 in US dollars. Long-term care expenditures, mostly paid by Medicaid, were not examined.

Hospital admission expenditures were estimated using in-patient data from the 2007 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Health-care Research and Quality.11 The NIS database represents an approximate 20% stratified sample of in-patient stays from more than 1000 hospitals located in 40 states. Matching with the NIS records was conducted as follows: (1) the diagnoses identified in the CASCADE study as the primary reason for admission were matched with the closest principal clinical classifications software or International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes; (2) secondary diagnoses were matched with the 15 secondary clinical classifications software or International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes; and (3) dementia was considered as a secondary diagnosis for all admissions. For each hospitalization, the estimated average charge was converted to an average cost using the charges-to-cost ratios provided by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

Expenditures for ED visits not resulting in a hospital admission were calculated from Medicare reimbursement rates for facility and physician services. Facility costs were based on the 2007 National Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System, which uses ambulatory classification codes to determine reimbursements.12 Physician costs were based on Current Procedural Technology (CPT) codes in the National 2007 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services physician fee schedule.12 In consultation with an ED physician with specific expertise in ED billing, ambulatory classification and CPT codes for evaluation and management services (ranging from 1 [lowest complexity] to 5 [highest complexity]) were assigned for each ED visit based on typical billing practices for specific diagnoses. Expenditures for laboratory services and other minor tests were not considered. However, estimates for the following investigations and procedures were included in ED expenditures: (1) unenhanced computed tomographic scan of the head for all head injuries; (2) bone x-ray films for fracture evaluations (eg, knee x-ray films for the evaluation of knee fractures); (3) chest x-ray films for questionable pneumonia; (4) suture repair for lacerations; and (5) replacement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for blockages or dislodgments.

Skilled nursing facility payment rates were estimated from the published 2006–2007 Medicare per diem fee schedule based on 53 Resource Utilization Group III codes.13 Information was available for 53 of 58 SNF-eligible hospitalizations in our cohort. Estimates for the remaining 5 cases were imputed using the average cost of the nonmissing data based on admissions that shared the same primary diagnosis.

Primary care provider unit costs were estimated using 2007 Medicare physician reimbursement rates obtained from the US Department of Health’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.14 Physician and nurse practitioner data from the CASCADE study included the number of visits but not the CPT codes. Therefore, the distribution of the CPT codes was estimated from a 2002 database of a nationally representative sample of NHs (n=202),15 which included all Medicare Part B claims submitted by physicians and nurse practitioners for residents with cognitive performance scores of 5 or 6 (severe to very severe cognitive impairment) (N = 18 243 claims).16 The average expenditures per visit for each provider type reflected the average reimbursement for services weighted by the frequency of CPT codes for each of the provider types. Hospice costs were based on the published 2007 Medicare per diem reimbursement ($130.79) for the “routine home care” category of hospice, a category that accounts for the vast majority of hospice days.17,18

OTHER VARIABLES

To examine factors associated with expenditures, variables were selected a priori from the CASCADE data set based on the literature.4,6–8,19,20 Baseline resident characteristics obtained from the chart included demographics (sex, race [white vs other], and age); whether or not the resident lived in a special care dementia unit; NH length of stay (<2 years, 2–5 years, and >5 years); and comorbidities (eg, congestive heart failure, active cancer, chronic obstructive lung disease); and presence of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube. Additional resident variables were collected at baseline and at each follow-up assessment. Cognitive status was measured by direct examination using the Test for Severe Impairment (TSI) score (range, 0–24; higher scores indicate better cognitive function).21 The TSI was categorized as either 0 or greater than 0 in these analyses. Functional status was quantified by the residents’ nurses using the Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity Scale (range 7–28; higher scores signify greater disability).22 The presence of a do-not-hospitalize (DNH) order was recorded. Finally, the determination was made as to whether the resident experienced at least 1 acute major illness (febrile episode, pneumonia, or other [eg, hip fracture, stroke, myocardial infarction]) in the interval between assessments.

Baseline HCP characteristics included sex, relationship to the resident (child vs other), and whether the HCP claimed to understand the health problems that are common in advanced dementia. At baseline and at every follow-up interview, it was also determined whether the HCP thought the resident had 6 months or less to live.

ANALYSIS

Means and proportions were calculated for all continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Health service use and expenditures were calculated for all residents (N=323) as well as separately for the subset of residents who died (n=177). The total number of hospital admissions, ED visits, primary care provider visits, and hospice admissions and the mean total number of days spent in the hospital and hospice were also determined. The total and mean expenditures were calculated for each Medicare service and for all services combined. Finally, mean expenditures for each 90-day period of follow-up were calculated as well.

Among residents who died, expenditures were allocated to each 90-day interval in the year before death (0–90 days, 91–180 days, 181–270 days, and 271–360 days). Mean expenditures during each interval were determined for (1) hospice services, (2) acute care services (inpatient and ED visits), (3) SNF services, and (4) provider services (physician and nurse practitioner primary care visits). Trends for intervals approaching death were estimated using generalized estimating equations, which were based on a gamma distribution and a log-link function for the mean.

Analyses were conducted to identify resident and HCP characteristics (independent variables) associated with total 90-day expenditures for 2 outcomes: (1) all Medicare services and (2) all Medicare services excluding hospice. We hypothesized that different factors would be associated with these 2 outcomes, as hospice represents a palliative approach to care, while other Medicare services (eg, hospitalizations) generally reflect a more aggressive approach. In both models, the level of analysis was the 90-day interval of observation corresponding to quarterly follow-up assessments. Static independent variables (eg, sex) came from the baseline assessments, while dynamic variables (eg, acute illness) were from the assessment closest to the 90-day expenditure interval. Because of the positive skewness, models assumed a gamma distribution, and mean 90-day expenditures were related to the covariates through a log link. Clustering at the resident level was accounted for using an exchangeable covariance structure. The measure of association for a characteristic was expressed as the natural log of the ratio of mean expenditures for observations with that characteristic relative to mean expenditures for observations without that characteristic. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated around this measure. Unadjusted associations between independent variables and 90-day Medicare expenditures were estimated. Independent variables associated with the outcome (P ≤ .10) were included in the multivariate model. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

The mean age of the 323 residents was 85.3 years; 85.5% were female; and 89.5% were white (Table 1). The mean age of HCPs was 59.9 years; 63.8% were female; and 67.5% were children of the resident (spouses, 10.2%; nieces or nephews, 8.7%; siblings, 5.0%; and grandchildren, legal guardians or friends, 8.6%). A total of 177 residents (54.8%) died during the study.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia and Their Health Care Proxies

| Characteristic | All Residentsa (N=323) |

|---|---|

| Resident | |

| Female | 276 (85.5) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 85.3 (7.5) |

| White race | 289 (89.5) |

| Special care dementia unit | 141 (43.7) |

| Nursing home length of stay, y | |

| <2 | 104 (32.2) |

| 2–5 | 100 (31.0) |

| >5 | 119 (36.8) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Congestive heart failure | 57 (17.7) |

| Active cancer | 4 (1.2) |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 36 (11.1) |

| Health care proxy | |

| Female | 206 (63.8) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 59.9 (11.6) |

| Child of resident | 218 (67.5) |

All values other than age are expressed as number (percentage).

MEDICARE SERVICES UTILIZATION AND EXPENDITURES

Table 2 presents use and expenditures for Medicare-covered services utilized by the entire cohort of residents (N=323) over the course of the study. Similar data are presented separately for the decedent subgroup (n=177). For the entire cohort, the total mean expenditures were $8522 per resident and $2303 per 90 days. Mean expenditures for hospitalizations were $2570 per resident and $625 per 90 days, accounting for 30.2% of total Medicare expenditures. Visits to the ED contributed only 1.1% to total expenditures, the lowest proportion of all services. Among the 58 hospitalizations eligible for follow-up, 31 (53.4%) resulted in an SNF stay, accounting for 11.3% of total expenditures (mean, $963 per resident and $234 per 90 days). There were 4826 recorded primary care visits, which accounted for 11.9% of total Medicare expenditures (mean, $1014 per resident and $247 per 90 days). Although only 22.0% of the cohort received hospice services, hospice payments accounted for 45.6% of total Medicare expenditures, the largest proportion of services examined. Mean hospice length of stay was 122.0 days, and mean spending was $3885 per resident and $1050 per 90 days.

Table 2.

Use and Expenditures Associated With Medicare Services Among Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementiaa

| Service | All Residents (N=323)

|

Residents Who Died Before End of Study (n=177)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mean (SD)b | Per 90 Daysc | Proportion of Total, % | Total | Mean (SD)b | Per 90 Daysc | Proportion of Total, % | |

| Inpatient | ||||||||

| No. of admissions | 74 | 0.2 (0.6) | … | … | 41 | 0.2 (0.6) | … | … |

| No. of days | 425 | 1.3 (4.4) | … | … | 256 | 1.4 (4.8) | … | … |

| Expenditures, $ | 830 105 | 2570 (7512) | 625 | 30.2 | 412 752 | 2332 (6832) | 928 | 33.2 |

| Emergency department | ||||||||

| No. of visits | 60 | 0.2 (1.3 | … | … | 15 | 0.1 (0.3) | … | … |

| Expenditures, $ | 29 059 | 90 (549) | 22 | 1.1 | 7656 | 43 (167) | 17 | 0.6 |

| Skilled nursing facility | ||||||||

| No. of admissions | 31 | 0.1 (0.4) | … | … | 17 | 0.1 (0.4) | … | … |

| No. of days | 905 | 2.8 (12.7) | … | … | 389 | 2.2 (10.6) | … | … |

| Expenditures, $ | 310 999 | 963 (4355) | 234 | 11.3 | 133 832 | 756 (3485) | 301 | 10.8 |

| Primary care provider | ||||||||

| No. of visits | 4826 | 14.9 (11.4) | … | … | 1797 | 10.2 (9.6) | … | … |

| Expenditures, $ | 327 593 | 1014 (823) | 247 | 11.9 | 120 729 | 682 (697) | 272 | 9.7 |

| Hospice | ||||||||

| No. of admissionsd | 78 | 0.2 (0.5) | … | … | 56 | 0.3 (0.5) | … | … |

| No. of days | 9516 | 29.5 (90.4) | … | … | 4291 | 24.2 (65.6) | … | … |

| Expenditures, $ | 1 254 799 | 3885 (11 859) | 1050 | 45.6 | 568 544 | 3212 (8617) | 1279 | 45.7 |

| Total, $ | 2 752 555 | 8522 (15 705) | 2073 | 100.0 | 1 243 513 | 7026 (12 919) | 2797 | 100.0 |

Expenditures are based on a 18-month observation period. All expenditures are based on nationally representative 2007 Medicare payment rates.

The mean is the average expenditure per resident over the entire 18-month observation period, independent of survival time.

The rate per 90 days is calculated as (total expenditure/total number of person-days) × 90 days.

There were a total of 78 hospice admissions; 71 of 323 residents (22%) had at least 1 admission (65 residents had only 1 admission; 5 residents had 2 admissions; and 1 resident had 3 admissions).

Medicare services provided to the subgroup of residents who died accounted for 45.2% of total expenditures. Mean expenditures per decedent were lower compared with all residents ($7026), but expenditures were higher on a per 90-day basis ($2797). The distribution of expenditures across services was comparable between the decedent group and the entire cohort.

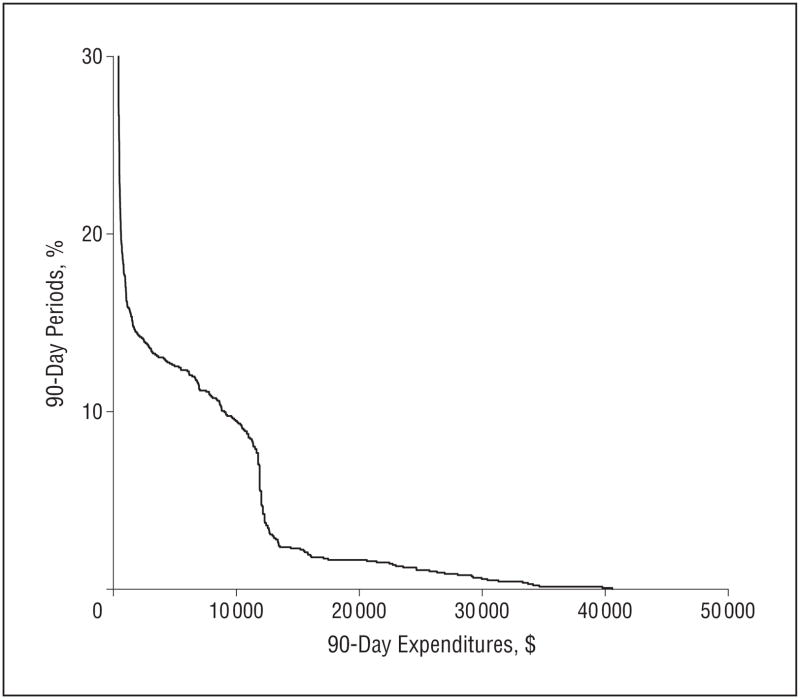

DISTRIBUTION OF 90-DAY MEDICARE EXPENDITURES

Figure 1 displays the distribution of total Medicare expenditures per 90-day interval for the entire cohort based on 1394 assessments, each representing 90 days of follow-up. Total expenditures were less than $500 for 77.1% of these 90-day intervals, between $500 and $12 000 for 17.4%, and exceeded $12 000 for only 5.5% of the 90-day intervals. A similarly skewed distribution of Medicare expenditures was seen among decedents.

Figure 1.

Distribution of 90-day Medicare expenditures among nursing home residents with advanced dementia (N=1394, 90-day assessments). Expenditures were less than $500 for 77.1% of the 90-day assessment periods and exceeded $12 000 for 5.5% of assessment periods.

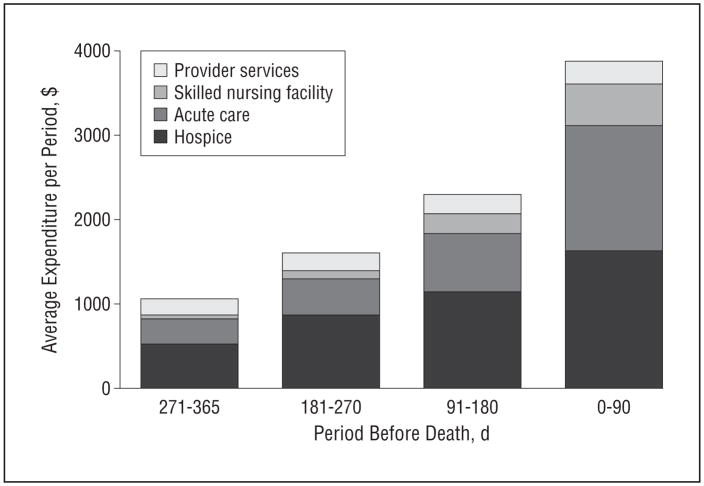

Figure 2 presents expenditures for each service incurred by decedents for each 90-day interval during the last year of life. Total mean Medicare expenditures increased as death approached as follows: 0 to 90 days before death, $3877 (n=177); 91 to 120 days before death, $2297 (n=128); 121 to 270 days before death, $1605 (n=96); and 365 to 271 days before death, $1061 (n=68). Mean total expenditures increased on average by 65% each period (P < .001). Mean expenditures for each individual service category also increased, with SNF and acute care showing the greatest proportional increases as death approached.

Figure 2.

Mean Medicare expenditures for nursing home residents with advanced dementia in the last year of life during the following 90-day intervals: 0 to 90 days before death (n=177); 91 to 120 days before death (n=128); 121 to 270 days before death (n=96); and 365 to 271 days before death (n=68).

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH MEDICARE EXPENDITURES

Table 3 presents the multivariate analyses examining factors associated with 90-day expenditures in the total cohort. After clustering at the individual level was adjusted for, the 6 factors independently associated with higher total Medicare expenditures were younger age, not living in a special care dementia unit, a TSI score of 0, chronic obstructive lung disease, acute illness in the prior 90 days, and a belief by the HCP that the resident has less than 6 months to live.

Table 3.

The Association Between Resident and Health Care Proxy (HCP) Characteristics and 90-Day Medicare Expenditures Among Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia

| Variable | All Assessments (N=1394)a | Relative Expenditures (95% CI)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For All Medicare Services

|

For All Medicare Services Excluding Hospice

|

||||

| Unadjusted | Adjustedb | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||

| Male resident | 176 (12.6) | 1.52 (0.95–2.45)c | 1.18 (0.63–2.19) | 2.35 (1.31–4.22)d | 1.02 (0.68–1.52) |

| White race | 1252 (89.8) | 0.73 (0.46–1.16) | … | 0.65 (0.33–1.27) | … |

| Resident age, mean (SD), y | 84.9 (7.5) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99)d | 0.98 (0.95–1.00)d | 0.96 (0.93–0.98)d | 0.97 (0.96–0.99)d |

| Did not live in special care unit for dementia | 800 (57.4) | 1.45 (0.96–2.19)c | 1.77 (1.18–2.65)d | 1.63 (0.99–2.68)c | 1.43 (1.03–1.97)d |

| Nursing home length of stay, y | |||||

| <2 | 465 (33.4) | 0.93 (0.59–1.48) | … | 1.24 (0.70–2.11) | … |

| 2–5 | 438 (31.4) | 0.88 (0.55–1.41) | … | 0.62 (0.33–1.16) | … |

| >5 | 491 (35.2) | 1 [Reference] | … | 1 [Reference] | … |

| Score 0 on the TSIe | 1136 (81.5) | 1.72 (1.20–2.47)d | 1.87 (1.35–2.58)d | 1.70 (1.03–2.80)d | 1.37 (1.00–1.88)d |

| Score on Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity Subscale, mean (SD)f | 21.4 (2.2) | 1.08 (1.02–1.14)d | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) | … |

| Comorbid baseline conditions | |||||

| Congestive heart failure | 206 (14.8) | 1.49 (0.92–2.40) | … | 2.10 (1.18–3.76)d | 1.29 (0.82–2.02) |

| Active cancer | 20 (1.4) | 0.51 (0.15–1.72) | … | 0.26 (0.13–0.52)d | 0.38 (0.24–0.61)d |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 142 (10.2) | 2.15 (1.31–3.52)d | 2.17 (1.28–3.69)d | 2.31 (1.21–4.40)d | 1.94 (1.14–3.30)d |

| Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube | 103 (7.4) | 1.51 (0.82–2.78) | … | 3.00 (1.62–5.58)d | 2.31 (1.08–4.92)d |

| Acute illness in previous 90 daysg | 438 (31.4) | 2.06 (1.55–2.74)d | 1.91 (1.42–2.58)d | 5.12 (3.44–7.61)d | 3.95 (2.91–5.37)d |

| No do-not-hospitalize order | 675 (48.4) | 1.47 (1.00–2.17)d | 1.39 (0.91–2.13) | 3.61 (2.33–5.60)d | 2.68 (1.96–3.67)d |

| Female proxy | 883 (63.3) | 1.22 (0.82–1.82) | … | 1.18 (0.71–1.95) | … |

| Proxy is child of resident (vs other relationship) | 958 (68.7) | 0.97 (0.66–1.42) | … | 1.12 (0.67–1.88) | … |

| Proxy believes resident’s life expectancy is <6 mo | 161 (11.6) | 1.37 (0.99–1.89)c | 1.33 (1.00–1.76)d | 0.91 (0.54–1.53) | … |

| Proxy understands which health problems to expect | 1116 (80.1) | 0.98 (0.62–1.54) | … | 0.77 (0.45–1.33) | … |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; TSI, Test for Severe Impairment.

Analysis conducted at the assessment level. Resident and HCP assessments were conducted every 90 days (up to 18 months). A resident assessment was also done within 14 days of death. All values are expressed as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

All variables associated with 90-day costs with P<.10 in the unadjusted analyses were included in the adjusted model.

P<.10.

P<.05.

Scores on the TSI range from 0 to 24; lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment. The TSI was dichotomized as 0 or higher than 0.

Scores on the Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity Subscale range from 7 to 28; higher scores indicate greater functional disability.

Acute illness includes febrile episodes, pneumonia, or other major events such as fractures, strokes, or myocardial infarctions in the previous 90 days.

When hospice was excluded from total Medicare expenditures, factors independently associated with higher 90-day expenditures were younger age, not living in a special care dementia unit, a TSI score of 0, chronic obstructive lung disease, the presence of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube, recent acute illness, and lack of a DNH order. Active cancer at baseline was associated with lower nonhospice Medicare expenditures.

COMMENT

This study provides a detailed report describing Medicare expenditures among NH residents with advanced dementia. Throughout the residents’ clinical course, hospitalizations and hospice care accounted for the greatest proportion of expenditures. Expenditures were highly skewed: spending was less than $500 in 77.1% of 90-day assessments and more than $12 000 in 5.5% of assessments. In the last year of life, Medicare expenditures increased as residents approached death largely because of increasing use of acute care and hospice services. Not living in a special care unit was associated with higher total 90-day Medicare expenditures, regardless of whether or not hospice was included as part of these expenditures. The lack of a DNH order and the presence of a feeding tube were additional modifiable factors associated with higher 90-day Medicare expenditures when hospice was excluded from these expenditures.

Inconsistent methods hinder direct comparisons between the total expenditures that we observed in advanced dementia and those reported for other terminal illnesses. Nonetheless, limited available data suggest that our estimates of Medicare expenditures in this cohort of NH residents with end-stage dementia were relatively low compared with other Medicare patients at the end of life.8,19,20 This finding is likely explained, in part, by the fact that in the months before death most residents received only NH care, a costly non-Medicare service that is most often paid for by Medicaid; relatively few residents were hospitalized, in an SNF, or enrolled in hospice. In contrast, most Americans who are older than 65 years and dying of cancer or other terminal conditions are not cared for in NHs3 and therefore rely on Medicare services (eg, hospice or hospital) for their end-of-life care.

The increase in Medicare spending that we observed as patients with advanced dementia approached death is consistent with prior research.23 Also, we provide novel findings regarding the sources of those expenditures in end-stage dementia. Roughly one-third of all Medicare expenditures were for hospitalizations. Hospital transfers are potentially burdensome in advanced dementia. As we previously reported,7 most hospitalizations in this cohort were for conditions that were potentially treatable with the same efficacy and at reduced costs in the NH compared with the hospital setting (eg, pneumonia, 68%).24 Moreover, approximately 10% of Medicare expenditures were for SNF care after hospitalization; more than half of residents with a qualifying hospital stay transitioned to SNF status post discharge. Given that these residents were totally functionally and cognitively impaired, their ability to benefit from skilled nursing or intense rehabilitative therapies is questionable. Taken together, our observations support the notion that acute and subacute care in this population may be shaped not only by clinical need alone but also by financial incentives created by Medicare and Medicaid policies. For example, an SNF stay represents substantial financial benefit to NHs because daily Medicare SNF reimbursement is higher than Medicaid NH payments.

Hospice payments accounted for the largest proportion of all Medicare expenditures in our cohort. Hospice has been shown to benefit residents dying with dementia,25,26 although patients with dementia are relatively underserved by hospice.27 While only 22% of residents in our cohort received hospice care, hospice services accounted for close to half of the Medicare expenditures. Whether hospice services lower end-of-life expenditures remains unclear and appears to depend on the terminal diagnosis and the length of hospice stay.6,18 Total Medicare and Medicaid costs in the last month of life for NH residents with dementia are reported to be the same or slightly higher with hospice than without hospice.6

The rich CASCADE data set provided a unique opportunity to identify factors associated with higher Medicare expenditures in advanced dementia. The strong association between the lack of a DNH order and higher acute care expenditures supports the notion that advance care planning may be a key step toward preventing aggressive end-of-life care, while reducing costs.8 Tube feeding, a potentially burdensome intervention with no demonstrable benefits in advanced dementia,28 was also independently associated with higher nonhospice expenditures.

This study has several limitations. First, Medicare expenditures were not derived from claims data but were estimated from publicly available fee schedules. This commonly used approach likely underestimated Medicare expenditures in our cohort.5,8 Second, there may be inaccuracies in the utilization data obtained from chart reviews because of errors in both documentation and abstraction. Third, we did not examine Medicaid expenditures, which are expected to be less variable than Medicare expenditures.6 Fourth, we described expenditures only during a snapshot of the course of advanced dementia and the period leading up to death. However, it would be challenging to conduct a prospective study describing expenditures from the moment patients first meet the criteria for advanced dementia. Fifth, we are not able to make causal inferences between factors shown to be associated with expenditures. Finally, the generalizability of our findings outside the greater Boston area is uncertain in terms of both Medicare expenditures and clinical factors (eg, the CASCADE cohort had a relatively high use of DNH orders). Nonetheless, Medicare expenditures were based on national data, and our analyses focused on the association between clinical factors and expenditures. It is also notable that expenditures varied considerably among residents, even within the narrow region of this study.

Dementia is a terminal illness, yet prior work suggests that persons dying with this disease receive suboptimal end-of-life care.27 Medicare policies play a key role in shaping that care. This study demonstrates that a large proportion of Medicare care expenditures in advanced dementia are attributable to acute and subacute services that may be avoidable and may not improve clinical outcomes. Strategies that promote palliation in advanced dementia may shift expenditures away from these aggressive treatments in advanced dementia toward a more comfort care approach (eg, hospice); however, the net effect on total Medicare expenditures remains unresolved. Finally, a better understanding of fiscal incentives that may be driving the pattern of health care expenditures among NH residents with advanced dementia (eg, temporary cost shifting from Medicaid to Medicare) is needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported in part by grants R01AG024091 and K24AG033640 (Dr Mitchell) from the National Institute on Aging.

Role of the Sponsors: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Author Contributions: Mr Goldfeld and Dr Mitchell had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Goldfeld, Stevenson, Hamel, and Mitchell. Acquisition of data: Goldfeld and Mitchell. Analysis and interpretation of data: Goldfeld, Stevenson, Hamel, and Mitchell. Drafting of the manuscript: Goldfeld, Stevenson, Hamel, and Mitchell. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Goldfeld, Stevenson, Hamel, and Mitchell. Statistical analysis: Goldfeld, Hamel, and Mitchell. Obtained funding: Mitchell. Administrative, technical, and material support: Stevenson and Mitchell. Study supervision: Mitchell.

References

- 1.Deaths: leading causes for 2005. [Accessed July 23, 2010.];National Vital Statistics Reports Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_08.pdf.

- 2.Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. [Accessed May 25, 2010.];Alzheimer’s Association Web site. http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_facts_figures.

- 3.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bynum JP, Rabins PV, Weller W, Niefeld M, Anderson GF, Wu AW. The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, medicare expenditures, and hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Torgan R, et al. Longitudinal study of effects of patient characteristics on direct costs in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(6):998–1005. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000230160.13272.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller SC, Intrator O, Gozalo P, Roy J, Barber J, Mor V. Government expenditures at the end of life for short- and long-stay nursing home residents: differences by hospice enrollment status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1284–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169 (5):480–488. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Jones RN, Prigerson H, Volicer L, Teno JM. Advanced dementia research in the nursing home: the CASCADE study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(3):166–175. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200607000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139 (9):1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welcome to HCUPnet (Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project) [Accessed July 12, 2010.];Agency for Health-care Research and Quality Web site. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/

- 12.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; hospital out-patient prospective payment system and CY 2007 payment rates; CY 2007 update to the ambulatory surgical center covered procedures list; Medicare administrative contractors; and reporting hospital quality data for FY 2008 inpatient prospective payment system annual payment update program—HCAHPS survey, SCIP, and mortality. Final rule with comment period and final rule. Fed Regist. 2006;71(226):67959–68401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; prospective payment system and consolidated billing for skilled nursing facilities—update notice. Fed Regist. 2006;71(146):43158–43198. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Physician fee schedule look-up. [Accessed July 12, 2010.];Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/overview.aspx.

- 15.Katz PR, Karuza J, Intrator O, et al. Medical staff organization in nursing homes: scale development and validation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(7):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Update to the hospice payment rates. [Accessed July 12, 2010];Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.cms.gov/transmittals/downloads/R1094CP.pdf.

- 18.Stevenson DG, Bramson JS. Hospice care in the nursing home setting: a review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(3):440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, Lynn J. Medicare beneficiaries’ costs of care in the last year of life. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(4):188–195. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerman S, Gruber-Baldini AL, Hebel JR, et al. Nursing home characteristics related to medicare costs for residents with and without dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(1):57–65. doi: 10.1177/1533317507308778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albert M, Cohen C. The Test for Severe Impairment: an instrument for the assessment of patients with severe cognitive dysfunction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(5):449–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, Kowall NW. Measurement of severity in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49(5):M223–M226. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.m223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell DE, Lynn J, Louis TA, Shugarman LR. Medicare program expenditures associated with hospice use. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(4):269–277. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-4-200402170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruse RL, Mehr DR, Boles KE, et al. Does hospitalization impact survival after lower respiratory infection in nursing home residents? Med Care. 2004;42 (9):860–870. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135828.95415.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller SC, Gozalo P, Mor V. Hospice enrollment and hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Am J Med. 2001;111(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller SC, Mor V, Wu N, Gozalo P, Lapane K. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(10):1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finucane TE, Christmas C, Travis K. Tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 1999;282(14):1365–1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]