Abstract

Background

Latinos are less likely than non-Hispanic whites to be adequately treated for depression. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is strongly associated with depression. Less is known about how Latina IPV survivors understand depression.

Objective

To understand Latina women's beliefs, attitudes, and recommendations regarding depression and depression care, with a special focus on the impact of gender, ethnicity, violence, and social stressors.

Design

Focus group study.

Participants

Spanish-speaking Latina women with a lifetime history of IPV and moderate to severe depressive symptoms.

Approach

We used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to conduct a thematic analysis using an inductive approach.

Results

Thirty-one women participated in five focus groups. Women felt depression is caused by “keeping things inside”. They also felt that keeping things inside could lead to physical illness or an inability to function. Their inability to talk was fueled by issues such as stigma, fear, isolation, cultural norms, or simply “not having the words”. They felt that the key to treating depression was finding a way to talk about the things that they had kept inside. They greatly valued information about depression and appreciated learning from providers that their physical symptoms were caused by depression. They wanted confidential depression care programs that not only helped them deal with their depression, but also addressed the violence in their lives, gave them practical skills, and attended to practical issues such as childcare. They had negative attitudes toward antidepressants, primarily due to experiences with side effects. Negative experiences with the health care system were primarily attributed to lack of good healthcare insurance.

Conclusions

The concept of "keeping things inside" was key to participants' understanding of the cause of depression and other health problems. Clinicians and depression care programs can potentially use such information to provide culturally-appropriate depression care to Latina women.

KEY WORDS: Latinos, depression, violence, disparities, community-based participatory research

BACKGROUND

Studies consistently find that depressed Latinos are less likely than depressed non-Latino Whites to receive adequate treatment, even when controlling for socio-demographic differences.1–3 Understanding cultural perspectives on depression and depression care may be a critical step in reducing depression care disparities. An emerging literature has focused on the way Latinos identify what causes depression,4–7 how they manage physical and emotional symptoms of depression,8 and how they understand depression care treatment outcomes.9–11

There is a well-recognized, strong association between depression and IPV. 12–17 Several studies have confirmed the relationship between IPV and depression in Latina women.12,18,19 IPV also may negatively affect mental healthcare-seeking behaviors, with lower use of mental health services in depressed women with a history of IPV than in depressed women without an abuse history.20,21 A history of IPV may potentially compound depression care disparities for Latina women.

Little is known about how Latina women conceptualize the relationship between violence and depression. This type of information can help us understand how to provide culturally appropriate depression care for the vulnerable and understudied population of Latina women who have experienced IPV. Our objective was to understand Latina women’s beliefs, attitudes, and recommendations regarding depression and depression care, with a special focus on the impact of gender, ethnicity, violence, and other social stressors.

METHODS

Community-Based Participatory Research

We used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach throughout the project. We formed an academic-community partnership (Proyecto Interconexiones / the Interconnections Project) consisting of academic researchers, healthcare providers, domestic violence advocates, IPV survivors, community members, and community leaders from both the Latina and African-American communities. The principal investigator (PI) had originally intended to work with community members to help increase the cultural relevance of a health-system-based depression care intervention, so she and the executive directors from two community agencies applied for an additional grant to support the CBPR aspects of the project. However, once the project began, community partners felt that the intervention would not be successful within the health system, so the entire project moved to the community, including the focus groups and the intervention.

Community partners and the PI acted as equal partners in each phase of the project. The entire team met at least monthly and worked collaboratively to design protocols and materials, collect data, analyze results, and use findings to design the intervention. The African-American and Latino portions of the study were designed together, but were then implemented and analyzed separately. This manuscript addresses findings from the focus groups with Latina women. Findings from focus groups with African-American women are presented elsewhere.22

Translation and Interpretation Issues

Joint meetings with the Latino and African-American portions of the team were conducted using simultaneous translation. Latino team meetings were conducted in Spanish. Whenever possible, we used survey instruments that had previously been translated and validated in Spanish. The remaining data collection instruments, as well as all recruitment and consent materials, were translated from English into Spanish and then back-translated by two community members to ensure accuracy and cultural relevancy. Focus groups were conducted and transcribed in Spanish and translated into English. Some members of the team analyzed transcripts in English while others analyzed them in Spanish. Meetings to decide on themes and reconcile differences were conducted in Spanish.

Recruitment and Eligibility

Community partners recruited participants primarily by word of mouth. They also distributed flyers about the study at social service agencies. The flyers and recruitment scripts did not mention violence or depression so as to not bias the sample. Potential participants were screened for eligibility either by the community partners or a Latina research assistant. Focus group participants were offered $50.

To be eligible, participants had to be female, at least 18 years of age, consider themselves to be Latina, Hispanic, or of Latin American descent, speak Spanish, score 15 or higher on the depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)23 and have a lifetime history of IPV. Physical or sexual IPV was assessed using 2 items (one about being hit, slapped, kicked or otherwise physically hurt by an intimate partner and the other about forced sex). Emotional abuse was measured by a score of 20 or greater on the Women’s Experiences of Battering (WEB) scale24, modified to ask about lifetime experiences. Emotional abuse was only assessed systematically if participants denied physical or sexual IPV.

Eligible participants were invited to a focus group by the community partners or research assistant. Potential participants were warned that their attendance would signify that they had depressive symptoms and a history of IPV to other participants attending the focus group.

Data Collection

Focus groups were held in private community settings. Informed consent was obtained prior to the start of the focus group discussion. The consent form, jointly created by academic and community partners, stated that we will ask all participants to keep what is stated in the focus groups confidential, but that we could not guarantee that other participants would maintain their confidentiality. It also explained that excerpts of what they said would be used in publications. Participants first completed a short demographic questionnaire. Then focus groups began with a discussion of “ground rules” that stressed the importance of respecting other’s confidentiality and reminded participants that they could step out at any time if needed. On a few instances, individual participants did choose to take a break when they became emotional. They received immediate counseling from the PI (a general internist) or from community partners who were experienced promotoras/domestic violence advocates. All felt well enough to voluntarily re-join the focus group session.

Focus groups used a structured interview guide created collaboratively by the academic and community partners. First, women were asked several questions about their experiences and beliefs about overall health, mental health, depression, depression treatments, and violence, as well as the inter-relationship between physical health, mental health, and violence. After being asked to share their recommendations for improving depression care, they were presented with the teams’ ideas for possible depression interventions and asked to respond to them. At the end of the session, to increase validity, the facilitator summarized what she had heard the women say and asked them to respond. Finally, each woman was asked to state the single most important point she wanted to make.

An expert in focus group research and the PI conducted an all-day training for the African-American and Latina community members of the team on how to facilitate focus groups. Training included role-play sessions where learners took turns moderating mock focus groups. Community partners had prior experience facilitating domestic violence support groups. Role-plays focused on the similarities and differences between the facilitator’s role in a support group vs. a focus group setting. We also included scenarios for how to handle difficult situations. Two Latina community partners (MP and AA) and one Latina research assistant (HG) facilitated the focus groups. The PI listened to the focus group discussion via a remote headset in a separate room and met with the facilitators during breaks. Interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

Both academic and community team members participated in the thematic analysis25 using an inductive approach at a semantic level, with an essentialist paradigm (i.e., we theorized motivations, experiences and meanings from what participants said rather than theorize the socio-cultural contexts and structural conditions that enabled the individual accounts). The PI and the lay facilitators met regularly to discuss preliminary themes. After all focus groups were completed, team members met to create an exhaustive list of preliminary codes. The PI and a research assistant (AH) formally coded all transcripts using Atlas-Ti software (Version 5.2). Three community partners (MP, AA, RA) independently coded the transcripts by making notations onto the transcripts. The group then met to compare findings and refined what they felt were the key messages. The group collaboratively decided on a framework that collapsed codes into major themes and sub-themes. A different Latina research assistant, (AM), re-checked the coding to assure that it fit with the final coding structure. The group met one last time to resolve any inconsistencies.

Results

We screened a total of 78 women, 48 of whom (62%) were depressed. Of those, 45 women (94%) had a history of physical and/or sexual IPV and the remaining three women (6%) had a history of emotional battering alone. We invited the 45 eligible women to the focus groups;31 women (66%) attended one of five focus groups. All focus group participants had a lifetime history of physical or sexual IPV. Table 1 describes their demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Sample, Mean (Range) or % |

|---|---|

| Age | 33.9 (19–48) |

| Foreign Born | |

| Mexico | 83% |

| Central America | 6% |

| Spanish Caribbean | 3% |

| Years in U.S. | 16 (1.4–43 years) |

| Annual household income, $ | |

| <15,000 | 64% |

| 15,000–24,999 | 16% |

| 25,000–69,999 | 10% |

| Education | |

| Less than high | 68% |

| High school | 16% |

| Some college | 3% |

| Employment | |

| Working or studying full time | 3% |

| Working or studying part time | 10% |

| Disabled | 3% |

| Unemployed | 58% |

| Insurance coverage | |

| Private | 10% |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 32% |

| No coverage | 48% |

| Lifetime physical or sexual IPV victimization | 100% |

| Currently involved with abusive partner | 55% |

| Currently has primary care provider | 15% |

| Currently has mental health provider | 35% |

| Ever treated for depression | 55% |

| Ever sought domestic violence services | 58% |

| Source through which participant learned about study | |

| Community advisory board member | 83% |

| Service provider | 6% |

| Flyer posted at: | |

| Health clinic | 6% |

| Domestic violence shelter | 3% |

Common Themes around Depression

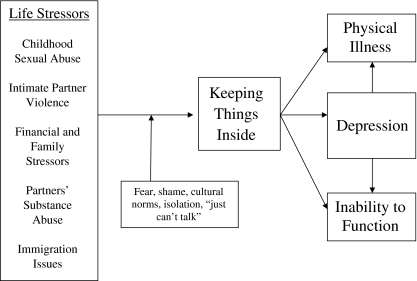

We identified a number of common themes regarding women’s beliefs about depression. Community and academic partners used these themes to create a model (Fig. 1) describing how participants understood the relationship between life stressors, depression, and health.

Figure 1.

Participants’ understanding of the relationship between life stressors, depression, and health.

Violence and Other Life Stressors Affect Health and Well-Being

Participants discussed many life stressors they felt effected their health and well-being. Such stressors included exposure to childhood sexual abuse, experiences of emotional, physical and sexual abuse from intimate partners, their partners’ use of alcohol or drugs, difficult relationships with family members, poverty, and stressors related to their immigration status.

“Every time I was raped—because I was raped more than once—my uncle raped me from when I was 8 years old until I was 11 years old —every time he was raping me he told me I was ‘meat to feed the dogs’—and everything, every single thing—from headaches—everything comes back to that. I mean, everything, in my case, everything is related.”

The stressors themselves were often inter-related—for example, many women talked about childhood sexual abuse leading to a lack of interest or comfort with sex, which then led to marital conflict or inability to sustain intimate relationships.

“I was sexually abused… and it is horrible. It doesn’t go away. It is the worst; and that’s why you can’t have relations with your partner sometimes; because you feel—and you remember—you were hurt. You feel revulsion having sex with your husband.”

“Holding Things Inside” Causes Depression and Physical Illness

Participants often felt what was most harmful to their health and well-being was the need to keep negative experiences hidden.

“When you shake a bottle—a soda, for example—it has gas, so shaking that bottle will make it explode. It is the same. When you are holding up all the things inside—in your heart—it damages people—like me personally. There are many things that I, since I was little, I had been through…. No one knows what it is inside of my heart; I am the only one that knows.”

They Viewed Depression as a Direct Result of Holding Things Inside

“There are a lot of things, things like violence, or a lot of things that, maybe I can’t finish saying them, no, but each person has a lot of things, physically, emotionally, in your children, in your family, friendships, well, of everything that happens in the world. To me, if you don’t have an exit, it goes into your blood and becomes a depression.”

Inability to Talk

Many women felt a strong need to talk about all the things they had been holding inside.

“Every person—every person is and knows what is on their heart—every person knows—and it is our duty to take it out so we don’t have it inside anymore.”

However, they often lamented about not being able to do so. Sometimes, they had practical reasons for not speaking. However, most often they simply felt they “couldn’t talk”.

“I can’t talk. At times, it isn’t because I don’t want to talk about it, but because it is so difficult to get the words out of my mouth. I feel like there is something in my, something here that blocks my throat. I can’t get the words out to explain what I want to say.”

Depression Leads to Physical Illness

They also felt that there was a direct connection between depression and physical illness:

“Yes, because you know that violence brings depression and depression makes you sick, and sicknesses brings more sickness.”

“The mind controls your body, your eyes, everything you do. If your mind is—like people say—if depression attacked it, you don’t have the control of doing things. It starts with your heart—the circulation of blood.”

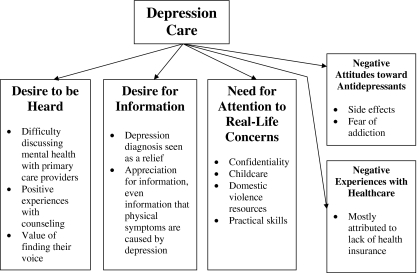

Common Themes Around Depression Care

Figure 2 summarizes themes about their experiences with depression care and their desires for what would be included in a depression care program.

Figure 2.

Common themes related to depression care.

Desire to be Heard

Women felt the key to healing was being able to talk about their depression and the experiences they were holding inside.

“Talking will cure you. Cure is when you talk and get it all out.”

Unfortunately, they often did not feel comfortable discussing mental health issues or life stressors with healthcare providers, fearing that their experiences would not be validated:

“Like when you go to do the pap smear exam, you only talk about that. Or if you have a headache, you only talk about that. But you never get to talk about how sad you feel or if I have something more private to share. I think sometimes we don’t focus on saying: ‘look, I have problems with my family or my husband that hit me’. You never say those things. You can’t talk about that because you are not comfortable. You go to the doctor exclusively not to talk about how sad you feel because they may tell you: ‘anyone goes through that’.”

In contrast, those that had experience with counseling related very positive experiences, especially around being able to talk:

“So I feel good with my counselor because I tell him everything; I open up, and I feel relief. So when I tell him my stuff I feel relief and depression goes away.”

Though they were in the minority, a few women did feel like they had succeeded in finding their voices:

“I had to do things that were so ugly… I felt like no one would believe me or maybe I felt like I would never be able to talk about it, but this thing that was so bad … It is something that I thought I would never talk about, that would never be revealed and that no one would ever know what I had lived through, but no. There came a time when I figured out what I had to say.”

Desire for and Appreciation of Health Information

Women were very interested in obtaining factual health information. They often felt that a depression diagnosis was a great relief:

“I didn’t know what depression was…. But when they started giving me the magazines… the symptoms that were described there—that’s what I was feeling.”

In contrast to our findings with non-Hispanic White women,26 who were concerned that providers would attribute physical symptoms to their mental health or abuse histories, women appeared to be grateful when providers told them that physical symptoms were caused by depression, often seeing it as a source of new information.

“I, thank God, went to urgent care because my depression stopped this part of my hands from working so that I wasn’t able to hold onto a gallon of milk. And at night my fingers would hurt and my hands would swell. And so I went to urgent care, but the nurse told me, “Look, … it could be that the depression is affecting your hands.” And they referred me < to counseling>, thank God.”

Desire for Depression-Care Program that Addressed Real-Life Needs

Latinas in our sample indicated that an ideal treatment program would not only address their mental health concerns, but would ensure confidentiality, provide childcare, help them address the violence in their lives, and give them accurate information and practical skills.

Negative Attitudes About Antidepressants

Though a few women related positive experiences with antidepressants, most had relatively negative attitudes toward antidepressants, primarily due to experiences with side effects.

“They gave me medication and instead of feeling better, I felt worse. The medication inflamed this whole part and my heart felt like it was accelerated badly and my veins (pulse) were irregular here in my feet and in my hands so that’s how I was with the medication and then later I told the doctor, ‘You know what? Instead of feeling good, I feel worse’.”

They also were concerned that antidepressants were addictive:

“I took antidepressants, but no, like for a month only. I didn’t want to be addicted to those pills, true. Because I saw relatives that, if they didn’t take them, they were like, they could not handle it, and they were bad with their children and everybody around them; so I didn’t want to be addicted to it.”

Negative Experiences With Healthcare Attributed to Lack of Health Insurance or Class Issues

Women often discussed experiences of discrimination in healthcare. Though there were mixed opinions as to whether or not the discrimination related to their race or ethnicity, there was general concensus that the problem was due to a lack of good health insurance.

For example, after hearing of an experience where a participant felt her family was not treated as well as a White family, the facilitator asked: “So you feel that was because of your color?” The participant replied: “Not because of the color—because of the insurance. Because you can see that the parents of that kid had money.”

Some participants related insurance status back to ethnicity:

“Well, for example, we, Latinas, we don’t have the same [health insurance] benefits that Americans do, or even other races. Some of them have more benefits than we do. I feel like Latinos, Hispanics, are the ones with less benefit after all.

Latina women were less interested in the race or ethnicity of health care providers than were African-American women22, as long as providers spoke Spanish fluently and understood their culture.

“We really don’t have fear of racism or what have you, but we want them to understand what we want to say.”

DISCUSSION

The concept of "keeping things inside" was key to Latina IPV survivors’ understanding of the cause of depression and physical health problems. Ultimately, they wanted to find their voice—a voice that had been suppressed due to a multitude of social factors. They desired programs that would help them address their experiences in a confidential, culturally-appropriate manner and would provide them with accurate information and practical skills.

Participants in our study saw a strong link between their depressive symptoms and their experiences of childhood sexual abuse, IPV, and other life stressors. Several other qualitative studies of Latinos have noted that Latinos perceive depression as being caused by an accumulation of interpersonal and social stressors.4,5 Our study adds to this literature by further examining participants’ understanding of the nature of that link. Participants seemed to feel that depression was not simply caused by having had these experiences, but more specifically by not being able to talk about them. Just as they had not felt comfortable talking about such experiences with family or friends, they also avoided talking about them with healthcare providers.

Our sample, unlike the samples in other qualitative studies on depression in Latinos, was limited to women who had experienced IPV. Additionally, a majority of women spontaneously disclosed a history of childhood sexual abuse. It is possible that abuse survivors place a greater emphasis than non-abuse survivors on the importance of talking about life stressors because they, in fact, have greater barriers to discussing life stressors, be it due to the classic isolation that abuse survivors experience, social taboos against discussing abuse, or the dangers associated with disclosing abuse.27 However, given the high lifetime prevalence of abuse amongst women with depression, it is likely that other samples also included many abuse survivors. Participants in our study knew that everyone in the room had experienced abuse and thus may have felt more comfortable talking about what they normally cannot discuss.

Women in our study felt that depression could directly lead to physical illness and expressed appreciation toward providers who made them aware that their somatic symptoms could be caused by depression. This finding is in direct contrast to what we have previously reported from a focus group study of non-Hispanic White women with depressive symptoms and histories of IPV.26 Participants in that study were often angered by suggestions that their physical symptoms were “caused” by mental health issues or abuse, and they worried that disclosing information to healthcare providers about abuse or mental health would lead providers to treat them “like hypochondriacs”. Participants in the current study had an opposite response to providers attributing physical symptoms to depression. Studies have noted a relationship between level of acculturation and the identification, perception, and role of somatization in Latinos in the US.28,29 Some have argued that somatization is more culturally accepted in Hispanic culture than it is in the US, and serves as an important modality for eliciting support.29 It is possible that our Latina participants—who had low levels of acculturation—did not have as strong negative perceptions of somatization as non-Hispanic IPV survivors and were thus more open to healthcare providers attributing physical symptoms to depression or mental health.

Among our participants, there was a strong desire to know what was wrong, to find ways to get better, and to demystify the many physical and emotional symptoms that made their already complicated lives less manageable. Participants’ motivation to understand and receive a diagnosis partly supports Nadeem’s findings that depressed immigrant Latinas were more open to treatment than depressed non-Hispanic White women.30 Although they cited stigma-related concerns when seeking mental health treatment, it was not as pronounced as in other minority women such as African, African American, or Caribbean Blacks. In our study, Latina women seemed less focused on concerns about racial discrimination than were African-American participants.22 Whether or not they made the connection between ethnicity and insurance status, they most often attributed negative experiences to lack of health insurance and wished for greater access to care. Only 15% of participants currently had a primary care provider, which highlights some of their difficulty accessing care and may contribute to their not having felt comfortable discussing abuse.

Their openness to depression treatment, however, did not indicate receptiveness to antidepressant medications. Multiple other studies have noted an apprehension toward antidepressants in minority populations, including Latinos and African-Americans.4,5,31,32 Our study adds information as to how women conceptualize their aversion toward antidepressants. For example, in the African-American portion of the study,22 participants also had negative attitudes toward antidepressants, but they framed their objections in terms of the need for self-reliance and a distrust of the White providers prescribing the medications. Latina participants voiced less overt distrust of the healthcare system, but often justified their hesitation toward antidepressants by citing adverse effects they had experienced or heard about from others.

Our study has a number of limitations. It describes a small, non-random sample of women in a single city. As with most qualitative studies, we were most interested in including informants who could best provide rich, in-depth information about the topic of interest. Results may not be generalizable to other populations, especially those with a greater degree of acculturation, without histories of violence or abuse, or with better access to healthcare services. Moreover, we did not separate focus groups by participants’ county or origin. Some studies have noted significant variation in IPV rates amongst different Hispanic sub-groups.33,34 A majority of women in our study were born in Mexico. Our results may be less applicable to women from other countries.

Despite these limitations, our study has some important implications for individual providers and depression care programs. Healthcare providers may use our findings in a number of ways. First, they should recognize that it may be very challenging for some of their Latina patients to discuss stressful life experiences. Still, they should actively inquire about life stressors, including experiences of violence and abuse, and encourage patients to talk about their experiences. Reinforcing the need to “not keep things inside” may be an appropriate way to encourage mental health counseling for Latina women, especially those that might hint at having had difficult life experiences. Providers should try to name depression as a clinical diagnosis and offer practical information to patients about depression and its treatment. Providers should still prescribe antidepressants when appropriate, but should pay close attention, both proactively and after starting treatment, to patients’ concerns about side effects and addiction, as such concerns may be a significant barrier to adherence. Rather than assuming that patients will be offended by attributing physical symptoms to mental health, providers should recognize that some Latina patients may be appreciative of information explaining the relationship between life stressors, mental health, and physical symptoms.

Our study also has implications for community or healthcare organizations interested in creating depression care programs for Latina women. Such programs should make sure to actively address life stressors such as childhood abuse or intimate partner violence, offering women a safe way to find their voice. Though race or ethnicity of staff seemed to be less of a factor for our Latina participants than for women in the African-American portion of our study, programs should make sure that staff speak fluent Spanish and are culturally competent. Programs would likely benefit by highlighting policies around confidentiality and offering practical supports such as childcare or skills training. Our academic-community partnership used results from this study to create a community-based depression care intervention for Latina women with a history of intimate partner violence. Future studies are needed to test the effectiveness of such depression-care programs for Latina women.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the women who participated in our focus groups, as well as the many community members who helped with recruitment efforts. We would also like to thank Kerth O’Brian, PhD, for leading the focus group facilitation training for the community partners, and Martha Gerrity, MD, PhD, Bentson McFarland, MD, PhD, and Mary Ann Curry, RN, DNSc, for providing mentorship and support to Dr. Nicolaidis.

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH073008; Nicolaidis) and the Northwest Health Foundation Kaiser Permanente Community Fund (10571; Nicolaidis).

We presented earlier versions of the manuscript as an oral abstract at the Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in Miami, in 2009 and as part of a workshop at the National Conference on Health and Domestic Violence in New Orleans, in 2009.

Conflicts of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al. Mental Health Care for Latinos: Inequalities in Use of Specialty Mental Health Services Among Latinos, African Americans, and Non-Latino Whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(12):1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, et al. Disparity in Depression Treatment Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(11):1264–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lagomasino IT, Dwight-Johnson M, Miranda J, et al. Disparities in depression treatment for Latinos and site of care. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(12):1517–1523. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabassa LJ, Hansen MC, Palinkas LA, Ell K. Azucar y nervios: explanatory models and treatment experiences of Hispanics with diabetes and depression. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(12):2413–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabassa LJ, Lester R, Zayas LH. "It's like being in a labyrinth:" Hispanic immigrants' perceptions of depression and attitudes toward treatments. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heilemann MV, Coffey-Love M, Frutos L. Perceived reasons for depression among low income women of Mexican descent. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2004;18(5):185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franks F, Faux SA. Depression, stress, mastery, and social resources in four ethnocultural women's groups. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13(5):282–292. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabassa LJ, Zayas LH. Latino immigrants' intentions to seek depression care. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(2):231–242. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez Pincay IE, Guarnaccia PJ. "It's like going through an earthquake": anthropological perspectives on depression among Latino immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9(1):17–28. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Interian A, Martinez IE, Guarnaccia PJ, Vega WA, Escobar JI. A Qualitative Analysis of the Perception of Stigma Among Latinos Receiving Antidepressants. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(12):1591–1594. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.12.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Perceived need for care among low-income immigrant and U.S.-born black and Latina women with depression. J Womens Health. 2009;18(3):369–375. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Cannon EA, Slesnick N, Rodriguez MA. Intimate partner violence in Latina and non-Latina women. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golding JM. Intimate Partner Violence as a Risk Factor for Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. J Fam Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1022079418229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell JC, Kub J, Belknap RA, Templin TN. Predictors of Depression in Battered Women. Violence Against Women. 1997;3(3):271–293. doi: 10.1177/1077801297003003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicolaidis C, Curry M, McFarland B, Gerrity M. Violence, mental health, and physical symptoms in an academic internal medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(8):819–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer H, Rodríguez M, Pérez-Stable E. Prevalence and determinants of intimate partner abuse among public hospital primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(11):811–817. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dienemann J, Boyle E, Baker D, Resnick W, Wiederhorn N, Campbell J. Intimate partner abuse among women diagnosed with depression. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2000;21(5):499–513. doi: 10.1080/01612840050044258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fedovskiy K, Higgins S, Paranjape A. Intimate partner violence: how does it impact major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder among immigrant Latinas? J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torres S, Han HR. Psychological distress in non-Hispanic white and Hispanic abused women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2000;14(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9417(00)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolaidis C, McFarland B, Curry M, Gerrity M. Differences in physical and mental health symptoms and mental health utilization associated with intimate-partner violence versus childhood abuse. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(4):340–346. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scholle SH, Rost KM, Golding JM. Physical abuse among depressed women. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(9):607–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolaidis C, Timmons V, Thomas MJ, et al. "You Don't Go Tell White People Nothing": African American women's perspectives on the influence of violence and race on depression and depression care. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1470–1476. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith PH, Earp JA, DeVellis R. Measuring battering: development of the Women's Experience with Battering (WEB) Scale. Womens Health. 1995;1(4):273–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Research Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolaidis C, Gregg J, Galian H, McFarland B, Curry M, Gerrity M. "You always end up feeling like you're some hypochondriac": intimate partner violence survivors' experiences addressing depression and pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1157–1163. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolaidis C. The Voices of Survivors documentary: using patient narrative to educate physicians about domestic violence. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(2):117–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen HT, Clark M, Ruiz RJ. Effects of acculturation on the reporting of depressive symptoms among Hispanic pregnant women. Nurs Res. 2007;56(3):217–223. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000270027.97983.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duran DG. The impact of depression, psychological factors, cultural determinants, and the patient/care-provider relationship on somatic complaints of the distressed Latina: Dissertation Abstracts International Section A. Humanit Soc Sci. 1995;56(6-A):2428. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, Miranda J. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S.-born black and Latina women from seeking mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(12):1547–1554. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodgkin D, Volpe-Vartanian J, Alegria M. Discontinuation of antidepressant medication among Latinos in the USA. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007;34(3):329–342. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kantor GK, Asdigian NL. Gender differences in alcohol-related spousal aggression. Gender and alcohol: Individual and social perspectives. 1997;312–34.

- 34.Kantor GK, Jasinski JL, Aldarondo E. Sociocultural Status and Incidence of Marital Violence in Hispanic Families. Violence Vict. 1994;9:207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]