ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Despite high rates of post-deployment psychosocial problems in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, mental health and social services are under-utilized.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate whether a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) integrated care (IC) clinic (established in April 2007), offering an initial three-part primary care, mental health and social services visit, improved psychosocial services utilization in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans compared to usual care (UC), a standard primary care visit with referral for psychosocial services as needed.

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort study using VA administrative data.

POPULATION

Five hundred and twenty-six Iraq and Afghanistan veterans initiating primary care at a VA medical center between April 1, 2005 and April 31, 2009.

MAIN MEASURES

Multivariable models compared the independent effects of primary care clinic type (IC versus UC) on mental health and social services utilization outcomes.

KEY RESULTS

After 2007, compared to UC, veterans presenting to the IC primary care clinic were significantly more likely to have had a within-30-day mental health evaluation (92% versus 59%, p < 0.001) and social services evaluation [77% (IC) versus 56% (UC), p < 0.001]. This exceeded background system-wide increases in mental health services utilization that occurred in the UC Clinic after 2007 compared to before 2007. In particular, female veterans, younger veterans, and those with positive mental health screens were independently more likely to have had mental health and social service evaluations if seen in the IC versus UC clinic. Among veterans who screened positive for ≥ 1 mental health disorder(s), there was a median of 1 follow-up specialty mental health visit within the first year in both clinics.

CONCLUSIONS

Among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans new to primary care, an integrated primary care visit further improved the likelihood of an initial mental health and social services evaluation over background increases, but did not improve retention in specialty mental health services.

KEY WORDS: veterans, mental health, health services utilization, primary care

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 2 million American men and women have served in the conflicts in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom, OEF) and Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom, OIF)1. The prevalence of mental health disorders has steadily increased: between 18.5% and 42% of OEF/OIF veterans are estimated to suffer from deployment-related mental health problems2–4. Further, mental health diagnoses in this population are typically comorbid with other mental and physical disorders5–8, resulting in a significant public health burden9–12.

Despite population-based mental health screening by the military and VA13, most OEF/OIF veterans with mental health problems, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), do not access or receive an adequate course of mental health treatment3,4,14,15. OEF/OIF veterans continue to report numerous barriers to mental health care, most notably stigma4,14,16,17. Nevertheless, OEF/OIF veterans with mental health disorders have significantly higher rates of primary care utilization than those without mental health disorders18,19.

In response, priorities were identified for VA primary care nationally20, some of which were operationalized at the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) in April 2007. These included: (1) monitoring rates of VA post-deployment mental health screening, (2) same-day mental health evaluations of veterans screening positive for PTSD and depression, and (3) limits on wait times for initial mental health appointments. In addition, on April 1, 2007, the SFVAMC OEF/OIF Integrated Care (IC) Clinic was established which offered integrated, co-located primary care, mental health and social services as described elsewhere and below21.

Since the establishment of the SFVAMC IC clinic in April 2007, most new OEF/OIF veteran patients initiating primary care have been scheduled for an initial IC visit, consisting of three optional 50-minute sessions with a team of primary care, mental health, and social services providers. IC providers have received training in post-deployment health, including an initial in-service, bi-monthly seminars on related topics (e.g. PTSD), and ongoing patient case-conferences. Due to scheduling constraints however (i.e.: limited number of 3-hour appointment blocks with trained providers), many new OEF/OIF veteran patients have been scheduled for “usual care” (UC), consisting of a standard 1-hour intake visit with a primary care provider (PCP) who has not received specialized post-deployment training, with referrals to mental health and social services as needed.

The main aim of this study was to evaluate whether an initial IC visit (compared to a UC visit) improved mental health and social services utilization in OEF/OIF veterans entering primary care at a VA medical center. First we compared UC primary care before and after April 1, 2007 to assess whether the introduction of the aforementioned national VA priorities led to background improvements in mental health services utilization that should be considered in evaluating any additional impact of the IC clinic. We hypothesized that over and beyond background changes, OEF/OIF veterans who had an initial IC versus UC primary care visit after April 2007 would be more likely to have received an initial mental health and social services evaluation, to have completed it in less time, and to have had a greater number of follow-up mental health visits within one year of initiating primary care.

METHODS

Setting/Intervention

This is a retrospective study based on data from the SFVAMC primary care clinics. In both the IC and UC primary care clinics, nurses conduct population-based VA post-deployment mental health and TBI screening using standard brief screens for PTSD (PC-PTSD)22, depression (PHQ-2)23, high-risk drinking (AUDIT-C)24,25, and TBI26. Then, in contrast to the UC clinic, where PCPs conduct a standard medical history and physical (H & P) exam, PCPs in the IC clinic conduct an H & P focused on deployment- and post-deployment-related medical and psychosocial problems. Following the PCP visit, patients in the IC clinic meet with a mental health provider, the “Post-Deployment Stress Specialist,” and social worker, the “Combat Case Manager.” Patients are informed that they may decline these additional visits.

The mental health portion of the IC visit typically consists of: (1) psychoeducation; (2) assessment of positive mental health screens and potential life-threatening problems (e.g. suicide); (3) brief intervention, if appropriate; and (4) referral for mental health treatment, if indicated. The social work visit consists of counseling about psychosocial concerns and veterans’ benefits. In contrast, unless a patient screens positive for PTSD or depression or makes a specific request, patients in the UC clinic are not routinely evaluated by a psychologist or social worker on the same day as their first primary care visit.

Study Population

The study population consisted of male and female OEF/OIF veterans presenting to the SFVAMC for their first primary care visit between April 1, 2005 and April 31, 2009. Because the IC clinic was established April 1, 2007, OEF/OIF veteran patients who presented for primary care prior to April 2007 were seen in the UC clinic. Of 605 OEF/OIF veterans, we excluded 79 veterans who had already received VA mental health treatment in the 60 days prior to their first SFVAMC primary care visit. This yielded a final study population of 526 OEF/OIF veterans whose health services utilization was followed through April 31, 2010. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of California, San Francisco, the San Francisco VA Medical Center, and the United States Department of Defense.

Source of Data

Data for this study, including identification of the study population, sociodemographics, mental health and TBI screen results, type of primary care received (IC vs. UC) and mental health and social services utilization, were extracted from the SFVAMC Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), and the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA). We also used the national VA OEF/OIF Roster database27 to obtain additional sociodemographic and military service information.

Definition of Study Variables

Dependent Outcome Variables

The main binary outcome variables were a same-day or within 30-day initial mental health evaluation, defined as an in-person encounter with a mental health clinician at the SFVAMC. We tabulated the number of “follow-up” specialty mental health visit(s) after the initial mental health evaluation within 1 year of initiating primary care. Similarly, we assessed for an initial social services evaluation, defined as an in-person or telephone visit within 30 days of initiating primary care.

Independent Variables

The main binary independent variable was primary care type: integrated care (IC) versus usual care (UC). Other independent variables included potential confounders: sociodemographics and military service characteristics (e.g. service branch and rank), as well as post-deployment mental health and TBI screen results.

Statistical Methods

Unadjusted chi square tests and relative risk calculations were used to compare characteristics of OEF/OIF veterans who received care in the UC versus IC clinic after April 2007 and, for background comparison, in the UC clinic before and after April 1, 2007. Unadjusted cox-proportional hazard models compared the number of days to the first mental health visit among UC versus IC patients. Generalized linear models using a Poisson distribution and robust error variance28 were used to estimate relative risks to determine the independent association between clinic type and mental health and social work evaluations within 30 days of the initial primary care visit after adjusting for potential confounding. Because there was a significant interaction between gender and clinic type, main effect and interaction terms were also included in the final multivariable models. All analyses were conducted using Stata (version 11.1)29.

RESULTS

Of 526 OEF/OIF veterans who initiated primary care at the SFVAMC during the study period, 12% were female, the median age was 28 [intraquartile range (IQR) = 25–37], 42% were ethnic minorities; and 39% were veterans of National Guard or Reserve service. Over half (61%) had a service-connected disability; 59% screened positive for ≥ 1 mental health problem(s) and 23% screened positive for a possible TBI. There were few significant differences in the sociodemographic, military service, and mental health characteristics of veterans presenting for UC before and after April 1, 2007, with the exception of age and service branch, and between veterans presenting for UC versus IC primary care after April 2007 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Characteristics of 526 OEF/OIF Veterans Initiating Primary Care at the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC) by Primary Care Category and Time Period

| Characteristics | Integrated Care (IC) Post-2007 (n = 230) | Usual Care (UC) Post-2007 (n = 117) | (IC vs. UC post-2007) | Usual Care (UC) Pre-2007 (n = 179) | (UC pre- vs. UC post-2007) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | p-values‡ | No. (%) | p-values‡ | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 209 (90.9) | 100 (85.5) | 154 (86.0) | ||

| Female | 21 ( 9.1) | 17 (14.5) | 0.147 | 25 (14.0) | 0.192 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 50 (21.7) | 15 (12.8) | 45 (25.1) | ||

| 25–29 | 86 (37.4) | 42 (35.9) | 53 (29.6) | ||

| 30–39 | 53 (23.0) | 32 (27.4) | 50 (27.9) | ||

| 40–49 | 31 (13.5) | 19 (16.2) | 26 (14.5) | ||

| >50 | 10 ( 4.4) | 9 ( 7.7) | 0.192 | 5 (2.8) | 0.040 |

| Race* | |||||

| White | 105 (45.7) | 44 (37.6) | 68 (38.0) | ||

| Black | 12 (5.2) | 6 (5.1) | 13 (7.3) | ||

| Hispanic | 30 (13.0) | 15 (12.8) | 28 (15.6) | ||

| Other | 53 (23.0) | 20 (17.1) | 0.411 | 33 (18.4) | 0.972 |

| Marital Status* | |||||

| Married | 47 (20.4) | 27 (23.1) | 45 (25.1) | ||

| Never married | 157 (68.3) | 62 (53.0) | 112 (62.6) | ||

| Divorced, widowed or separated | 11 (4.8) | 3 (2.6) | 0.330 | 9 (5.0) | 0.735 |

| Distance to SFVAMC(mi)* | |||||

| 0–30 | 171 (74.3) | 88 (75.2) | 105 (58.7) | ||

| 31–60 | 31 (13.5) | 14 (12.0) | 25 (14.0) | ||

| 60 + | 27 (11.7) | 14 (12.0) | 0.963 | 28 (15.6) | 0.235 |

| Service Connection* | |||||

| Yes | 131 (57.0) | 70 (59.8) | 116 (64.8) | ||

| No | 91 (39.6) | 46 (39.3) | 0.907 | 63 (35.2) | 0.460 |

| Component type* | |||||

| Active Duty | 135 (58.7) | 62 (53.0) | 94 (52.5) | ||

| National Guard/Reserve | 80 (34.8) | 30 (25.6) | 0.516 | 72 (40.2) | 0.111 |

| Rank* | |||||

| Enlisted | 180 (78.3) | 81 (69.2) | -- | ||

| Officer | 35 (15.2) | 11 (9.4) | 0.386 | -- | -- |

| Branch* | |||||

| Army | 123 (53.5) | 43 (36.8) | 87 (48.6) | ||

| Marine | 40 (17.4) | 15 (12.8) | 43 (24.0) | ||

| Air Force | 18 (7.8) | 11 (9.4) | 12 (6.7) | ||

| Navy/Coast Guard | 34 (14.8) | 23 (19.7) | 0.148 | 24 (13.4) | 0.048 |

| Multiple deployments* | |||||

| Yes | 90 (39.1) | 29 (24.8) | 47 (26.3) | ||

| No | 123 (53.5) | 63 (53.8) | 0.096 | 118 (66.0) | 0.669 |

| TBI*,† | |||||

| Positive | 56 (24.3) | 21 (17.9) | -- | ||

| Negative | 171 (74.3) | 84 (71.8) | 0.402 | -- | -- |

| Screen results* | |||||

| No positive screens | 88(38.3) | 57(31.8) | 39(21.8) | ||

| Single screen positive | 77(33.5) | 30(16.8) | 25(14.0) | ||

| Two or more screens positive | 64(27.8) | 28(15.6) | 0.276 | 34(19.0) | 0.140 |

*Numbers do not sum to column totals and percents do not total 100% due to missing values

†TBI screening began April 1, 2007 at the SFVAMC and thus, veterans in the UC group presenting before April 2007 were not screened

‡p-values are derived from unadjusted chi square tests

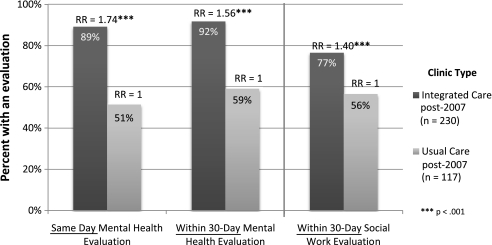

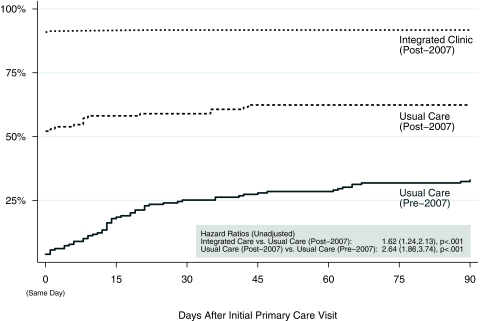

Figure 1 shows that among OEF/OIF veterans seen in the IC clinic after it was established in April 2007, 89% compared to 51% of UC patients had an initial mental health evaluation on the same day as their primary care visit (Unadjusted RR = 1.74, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 1.45–2.09). Extending the ascertainment period to 30 days did not significantly change this outcome (92% vs. 59%; Unadjusted RR = 1.56, 95% CI = 1.33–1.82) because the majority of visits occurred on the same day as the first primary care visit (Figs. 1 and 2). In addition, veterans seen in the IC versus UC clinic were significantly more likely to have had an initial social work evaluation within 30 days of their initial primary care visit (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Same-day and within 30-day mental health and social work evaluation by clinic.

Figure 2.

Comparison of time to first mental health evaluation by clinic type and time period.

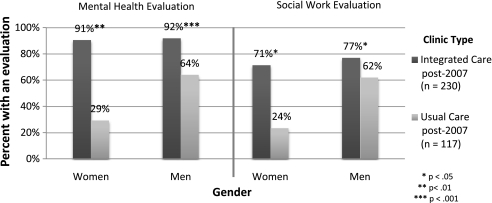

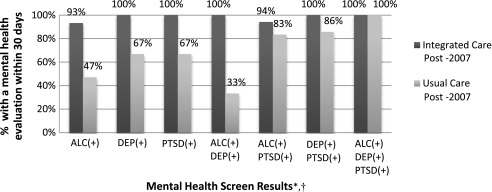

Both unadjusted and multivariable analyses demonstrated that female veterans who presented to the IC versus UC clinic were nearly three times more likely to have received initial mental health and social services evaluations within 30 days of initiating primary care (Table 2 and Fig. 3). In contrast, in unadjusted analyses, men were more likely to have had initial mental health and social services evaluations in IC versus UC primary care, but after adjusting for confounding and accounting for the interaction of gender and clinic, only the finding of increased mental health evaluations in men remained significant (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Veterans who screened positive for one or two mental health disorders, and who were first seen in the IC (versus UC) clinic, were also more likely to have had an initial mental health and social services evaluation within 30 days (Table 2 and Fig. 4). There was also a borderline significant increase in the likelihood of an initial mental health evaluation for younger aged veterans seen in the IC clinic (p = 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Independent Predictors of Receiving a Mental Health and Social Work Evaluation within 30 days of Initiating Primary Care (Post-2007 Integrated Care, N = 230; Post-2007 Usual Care, N = 117)*

| ARR† | [95% CI] | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health Evaluation within 30 Days | |||

| Usual Care | 1.00 | -- | -- |

| Integrated Care (Women) | 2.94 | 1.41, 6.18 | 0.004 |

| Integrated Care (Men) | 1.30 | 1.13, 1.50 | 0.001 |

| Positive Mental Health Screen | 1.15 | 1.05, 1.29 | 0.005 |

| Positive TBI Screenb | 1.10 | 1.03, 1.19 | 0.006 |

| Age (per 5 years) | 0.97 | 0.94, 1.00 | 0.054 |

| Social Work Evaluation within 30 Days | |||

| Usual Care | 1.00 | ||

| Integrated Care (Women) | 2.91 | 1.20, 7.09 | 0.019 |

| Integrated Care (Men) | 1.11 | 0.94, 1.31 | 0.213 |

| Positive Mental Health Screen | 1.17 | 1.01, 1.36 | 0.042 |

| Positive TBI Screenb | 1.06 | 0.92, 1.21 | 0.417 |

| Age (per 5 years) | 0.95 | 0.91, 1.00 | 0.031 |

*Poisson regression adjusted for age, mental health and traumatic brain injury screen results and having accounted for gender by clinic interaction

†Abbreviations: ARR = Adjusted Relative Risk; TBI = traumatic brain injury

Figure 3.

Within 30-day mental health and social work evaluation by gender.

Figure 4.

Mental health evaluation within 30 days by mental health screen result *Abbreviations: ALC (+) = Screened positive for high-risk drinking; DEP (+) = Screened positive for depression; PTSD (+) = Screened positive for posttraumatic stress disorder †Screen results are mutually exclusive. For example, ALC (+) denotes veterans who screen positive for high-risk drinking only, whereas ALC (+)/PTSD (+) represents veterans who screen positive for high-risk drinking and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Examining background trends in mental health services utilization, we found that 25% of veterans seen in the UC clinic before April 2007 compared to 59% who presented for care after April 2007 had at least one mental health evaluation within 30 days of initiating UC primary care (Unadjusted Relative Risk (RR) = 2.35, 95% CI = 1.75–3.15). UC primary care patients received an initial mental health evaluation after April 2007 in less time than before April 2007 (Fig. 2).

Among veterans completing an initial mental health evaluation, IC patients were significantly more likely than UC patients to have had at least one follow-up specialty mental health visit within 90 days of initiating primary care (42% versus 29%, p = 0.03). Of note, among veterans who screened positive for one or more mental health problem(s), in both the IC and UC clinics, the median number of specialty mental health visits in the first year was 1 (IQR = 0–6 and 0–7 visits, respectively), p = 0.90.

DISCUSSION

OEF/OIF veterans have a high prevalence of mental health problems, yet significant barriers to accessing mental health treatment prevent adequate treatment of these disorders4,14,16,30. Prior reports have suggested that OEF/OIF veterans may prefer to receive mental health services within a primary care setting21,31. Thus, clinicians at the SFVAMC developed the OEF/OIF Integrated Care Clinic to offer new OEF/OIF veteran patients, even those with negative mental health screens, the option of a same-day brief mental health and social services assessment in primary care21.

We found that patients seen in the IC clinic were significantly more likely to have had initial mental health and social work evaluations than UC patients. Because many VA-enrolled veterans screen positive for mental health disorders and/or TBI on the sensitive, but not highly specific universal VA screens, there are several potential benefits to facilitating access to psychosocial services13. Same-day psychoeducation and appropriate risk communication in primary care about the meaning of positive screen results may prevent iatrogenesis and promote recovery expectations32–34. Importantly, given the increased incidence of suicide and other high-risk behaviors among OEF/OIF veterans35–37, a same-day mental health evaluation provides the opportunity to further assess veterans with positive screens or symptoms using more specific instruments, as well as assess for personal safety. In addition, mental health clinicians may conduct a one-time brief intervention (e.g. for high-risk drinking)38, and schedule a referral, if indicated.

Improved access to psychosocial services might also benefit those with negative screens. It is well-established that the onset of PTSD and other mental health and psychosocial problems may be delayed after returning from war2,39. Learning about VA and non-VA mental health and social services resources and benefits during an initial primary care appointment may prove useful should symptoms develop in the future. Finally, while not a direct patient benefit, improved communication within the IC primary care, mental health and social service provider team may improve coordination of care across services.

Our results suggest that the co-located integrated care model may be of particular benefit in certain subgroups of OEF/OIF veterans. For instance, women were far more likely to have received mental health and social services (most often on the same day) if they presented to the IC rather than UC clinic. This is important given women veterans’ perceived barriers to care40, unique readjustment issues, and potentially greater mental health needs relative to male counterparts41,42. Moreover, despite VA expectations to conduct evaluations of all veterans with positive PTSD or depression screens20, our results revealed that veterans with positive screens were more likely to be evaluated if seen in the IC versus UC clinic. In addition, veterans who screened positive for TBI, endorsing symptoms such as poor memory and concentration, were also more likely to receive psychological and social services if seen in the IC clinic. This may be due to a lack of available mental health staff for same-day evaluations for UC patients or other barriers such as a lack of transportation, stigma, avoidance, or difficulties remembering a future appointment.

Unfortunately, while IC increased initial mental health evaluations, there was no significant increase in retention in specialty mental health services among veterans who screened positive for mental health problems. Collaborative Care models for the treatment of depression in primary care, such as the Translating Initiatives for Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES) model43–45, have demonstrated significant improvements in depression treatment completion rates in numerous randomized controlled trials46–50. Central to TIDES is the “Care Manager,” typically a nurse supervised by a psychiatrist, who provides ongoing support for anti-depressant medication adherence in primary care and conducts clinical outcomes assessments to guide PCPs’ decision-making regarding mental health treatment43,51.

Despite the efficacy of TIDES for older veterans with depression, collaborative care models may need to be modified to be most effective in OEF/OIF veterans. For example, younger and minority combat veterans with anxiety disorders may be reluctant to accept medication and may instead prefer psychotherapy50,52–54. Evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD and other anxiety disorders is typically delivered in specialty mental health settings, but a recent study of OEF/OIF veterans with new PTSD diagnoses in VA healthcare showed that veterans’ failed to attend an adequate number of specialty mental health visits required for evidence-based PTSD treatment55. The addition of a Care Manager to the IC Clinic to make reminder phone calls for specialty mental health visits could improve retention, yet funding this position through primary care has been challenging.

Because most individuals with post-traumatic stress, including OEF/OIF veterans, pursue medical treatment in primary care, models that integrate primary and mental health care may improve both engagement and retention of patients in mental health treatment18,19. To date however, there have been only two randomized controlled trials of collaborative care for anxiety disorders that resulted in improved clinical outcomes compared to usual care50,56. Both were conducted in non-veteran populations and only one of them, which included a relatively small number of PTSD patients, was conducted in a primary care setting50. Only one study has demonstrated the acceptability and feasibility among OEF/OIF personnel of providing pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy for PTSD in a primary care setting using collaborative care (RESPECT-Mil)53, but to date, there has been no randomized controlled trial of this program. Building on the IC model evaluated in this study and prior research on collaborative care, a next logical step to improve mental health treatment engagement in veterans with mental health symptoms would be to offer a brief psychotherapeutic intervention for post-traumatic stress in primary care following the initial IC visit. This brief intervention may be sufficient, or patients requiring further care could “step up” to specialty mental health treatment.

This study has some important limitations. Our results are based on administrative data from one urban VA medical center and thus, do not generalize to all VA and non-VA healthcare facilities serving OEF/OIF veterans. Further, because our data source was limited to VA, we were not able to capture mental health and social services received outside VA. In addition, study results may have been biased because veterans assigned to the IC clinic may have perceived the 3-part visit to be compulsory, not optional, although they were apprised of the option to decline. Because we were limited to retrospective data, we were also not able to prospectively assess other potential positive and negative clinical outcomes of the IC clinic. For instance, requiring a 3-hour intake visit may add to patient burden and pre-scheduling a mental health and social services visit for all veterans entering primary care could convey the unintended message that something must be wrong with veterans returning from war57.

In summary, an IC visit increased the likelihood that OEF/OIF veterans received an initial mental health and social services evaluation. This was especially true for female and relatively younger veterans, and those who screened positive for mental health disorders and TBI, potentially groups with greater barriers to care14. These results appear robust, even when we consider background increases in mental health services utilization that occurred in usual primary care after April 2007. Despite the increase in initial evaluations among IC patients, however, engagement in follow-up mental health treatment was poor, even among veterans who screened positive for mental health disorders. Future prospective studies of OEF/OIF veterans may shed more light on the clinical effectiveness of an initial IC visit. In addition, including brief mental health treatment interventions for PTSD spectrum disorders in primary care itself may further overcome barriers to mental health treatment and improve retention and clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Contributor We would like to thank Dr. Rina Shah and Dr. Dawn Lawhon for their leadership in the design and coordination of the SFVAMC Integrated Care Clinic. We acknowledge the support of the San Francisco VA HSR&D Research Enhancement Award Program. We would also like to thank Ms. Ann Chu for her assistance in data abstraction. Finally, we acknowledge and thank veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan for their service to our country.

Funders This study was funded by Department of Defense awards W81XWH-08-2-0072 and W81XWH-08-2-0106. The funders had no role in the design, data analysis, writing or approval of the manuscript.

Prior Presentations We presented limited, earlier versions of the data contained within this manuscript as posters/oral presentations at the following conferences: Evolving Paradigms II, Las Vegas, September 2009; Future Directions in PTSD: Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment, Jerusalem, Israel, October 2009; and the International Society for Trauma Stress Studies, Atlanta, GA, November, 2009.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Defense. Defense Manpower Data Center: Contingency Tracking System Deployment File. Data current as of Dec. 2009.

- 2.Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA. 2007;298:2141–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seal KH, Metzler TJ, Gima KS, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Marmar CR. Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs health care, 2002–2008. Am J Publ Health. 2009;99:1651–1658. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanielian TL, Jaycox LH, editors. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen J, Wade M, Possemato K, Ouimette P. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder and primary care provider-diagnosed disease among iraq and afghanistan veterans. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:498–504. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d969a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frayne SM, Chiu VY, Iqbal S, et al. Medical Care Needs of Returning Veterans with PTSD: Their Other Burden. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;26:33–39. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1497-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen BE, Marmar C, Ren L, Bertenthal D, Seal KH. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with mental health diagnoses in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans using VA health care. JAMA. 2009;302:489–492. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnurr PP, Green BL, Kaltman S. Trauma exposure and physical health. In: Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA, editors. Handbook of PTSD. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Bovin MJ, Marx BP. Posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life: extension of findings to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pietrzak RH, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Johnson DC, Southwick SM. Risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakupcak M, Cook J, Imel Z, Fontana A, Rosenheck R, McFall M. Posttraumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:303–306. doi: 10.1002/jts.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sayer NA, Noorbaloochi S, Frazier P, Carlson K, Gravely A, Murdoch M. Reintegration problems and treatment interests among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans receiving VA medical care. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:589–597. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.6.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Gima K, Chu A, Marmar CR. Getting beyond “Don’t ask; don’t tell”: an evaluation of US Veterans Administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Publ Health. 2008;98:714–720. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295:1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM. Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1118–1122. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.8.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim PY, Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Stigma, barriers to care, and use of mental health services among active duty and National Guard soldiers after combat. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:582–588. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:18–24. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1117-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoge C, Terhakopian A, Castro C, Messer S, Engel CC. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. Am J Psychiatr. 2007;164:150–153. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Veterans Affairs. Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics: Veterans Health Administration; 2008.

- 21.Maguen S, Cohen G, Cohen B, Lawhon GD, Marmar C, Seal KH. The role of psychologists in the care of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans in primary care settings. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2010;41:135–142. doi: 10.1037/a0018835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimmerling R, Camerond RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, Thrailkill A, Gusman FD, Sheikh JI. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatr. 2004;9:9–14. doi: 10.1185/135525703125002360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwab KA, Ivins B, Cramer G, et al. Screening for traumatic brain injury in troops returning from deployment in Afghanistan and Iraq: initial investigation of the usefulness of a short screening tool for traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22:377–389. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000300233.98242.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.OEF/OIF ROSTER. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2009.

- 28.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009.

- 30.Stecker T, Fortney J, Hamilton F, Ajzen I. An assessment of beliefs about mental health care among veterans who served in Iraq. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1358–1361. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.10.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batten S, Pollack S. Integrative outpatient treatment for returning service members. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64:928–939. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mittenberg W, DiGiulio DV, Perrin S, Bass AE. Symptoms following mild head injury: expectation as aetiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:200–204. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunt SC, Richardson RD, Engel CC, Jr, Atkins DC, McFall M. Gulf War veterans’ illnesses: a pilot study of the relationship of illness beliefs to symptom severity and functional health status. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:818–827. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000135529.88068.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VA Consensus Conference. Practice recommendations for treatment of veterans with comorbid TBI, pain, and PTSD. 2008.

- 35.Killgore WD, Cotting DI, Thomas JL, et al. Post-combat invincibility: Violent combat experiences are associated with increased risk-taking propensity following deployment. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:1112–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuhn E, Drescher K, Ruzek J, Rosen C. Aggressive and unsafe driving in male veterans receiving residential treatment for PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:399–402. doi: 10.1002/jts.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang HK, Bullman TA. Risk of suicide among US veterans after returning from the Iraq or Afghanistan war zones. JAMA. 2008;300:652–653. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients with alcohol problems: a clinician’s guide. NIH Pub No. 05–3769. Bethesda, MD: The National Institute of Health; 2005.

- 39.Andrews B, Brewin CR, Philpott R, Stewart L. Delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1319–1326. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vogt D, Bergeron A, Salgado D, Daley J, Ouimette P, Wolfe J. Barriers to Veterans Health Administration care in a nationally representative sample of women veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00370.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Street AE, Vogt D, Dutra L. A new generation of women veterans: stressors faced by women deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maguen S, Ren L, Bosch JO, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Gender differences in mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans enrolled in veterans affairs health care. Am J Publ Health. 2010;100:2450–2456. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.VA Health Services Research and Development Service. Collaborative care for depression in the primary care setting. A Primer on VA’s Translating Initiatives for Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES) Project. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2008.

- 44.Felker BL, Chaney E, Rubenstein LV, et al. Developing effective collaboration between primary care and mental health providers. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8:12–16. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v08n0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:91–113. doi: 10.1037/a0020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katon W, Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–1031. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.13.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katon W, Russo J, Korff M, et al. Long-term effects of a collaborative care intervention in persistently depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:741–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:378–386. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, et al. Delivery of evidence-based treatment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1921–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K. A three-component model for reengineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:441–450. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.6.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaik DJ, Klijn AF, Hout HP, et al. Patients’ preferences in the treatment of depressive disorder in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Engel CC, Oxman T, Yamamoto C, et al. RESPECT-Mil: feasibility of a systems-level collaborative care approach to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in military primary care. Mil Med. 2008;173:935–940. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.10.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zoellner LA, Feeny NC, Bittinger JN. What you believe is what you want: modeling PTSD-related treatment preferences for sertraline or prolonged exposure. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2009;40:455–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seal KH, Maguen S, Cohen B, et al. VA mental health services utilization in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the first year of receiving new mental health diagnoses. J Trauma Stress. Feb;23:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of stepped collaborative care for acutely injured trauma survivors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:498–506. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wessely S, Bryant RA, Greenberg N, Earnshaw M, Sharpley J, Hughes JH. Does psychoeducation help prevent post traumatic psychological distress? Psychiatry. 2008;71:287–302. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]