Abstract

We describe a novel type of human thrombocytopenia characterized by the appearance of giant platelets and variable neutropenia. Searching for the molecular defect, we found that neutrophils had strongly reduced sialyl-Lewis X and increased Lewis X surface expression, pointing to a deficiency in sialylation. We show that the glycosylation defect is restricted to α2,3-sialylation and can be detected in platelets, neutrophils, and monocytes. Platelets exhibited a distorted structure of the open canalicular system, indicating defective platelet generation. Importantly, patient platelets, but not normal platelets, bound to the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGP-R), a liver cell-surface protein that removes desialylated thrombocytes from the circulation in mice. Taken together, this is the first type of human thrombocytopenia in which a specific defect of α2,3-sialylation and an induction of platelet binding to the liver ASGP-R could be detected.

Several types of hereditary macrothrombocytopenia have been described, including Bernard-Soulier syndrome and the May-Hegglin anomaly, which are caused by mutations in the genes coding for platelet glycoproteins (GP) Ib/IX and nonmuscle myosin heavy chain, respectively.1,2 Macrothrombocytopenia can also be caused by a defect in glycosylation.3 This disease, termed congenital disorder of glycosylation-IIf (CDG-IIf), was detected in a child whose neutrophils lacked expression of the sialic acid–containing tetrasaccharide sialyl-Lewis X (sLex) and showed increased expression of its nonsialylated form Lewis X (Lex). Notably, abnormal demarcation membranes in megakaryocytes strongly pointed to a defect in the generation of thrombocytes.3 Mutations in the gene encoding the Golgi transporter for cytidine monophosphate (CMP)-sialic acid were described as the cause for this disease.4

Generally, sialylation appears to strongly affect the number of circulating platelets. Indeed, desialylation of platelets results in their clearance from the circulation.5 Moreover, mice deficient for α2,3-sialyltransferase IV show strong thrombocytopenia.6,7 Interestingly, as in CDG-IIf, platelets are enlarged in these mice. Recently, experiments in mice have shown that hyposialylated platelets readily bind to the liver asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGP-R) in vivo and are efficiently removed from the circulation by the ASGP-R, explaining the induction of thrombocytopenia.8,9 Here, we present the first type of human macrothrombocytopenia that is associated with a specific defect of α2,3-sialylation and with strong platelet binding to the ASGP-R.

Materials and Methods

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed according to standard protocols.10 Anti-sLex antibody CSLEX-1 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), anti-Lex antibody (BD Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany), negative control IgM monoclonal antibody (mAb) (BD Pharmingen), anti-GQ1b/GD3 mAb R24,11 anti-PSA mAb 735,12 anti-Lea antibody (Acris Antibodies, Hiddenhausen, Germany), and anti-GP1b mAb AK2 (Serotec, Düsseldorf, Germany) were used at 10 μg/mL. Biotinylated Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL), concanavalin A, peanut agglutinin, Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA), and Maackia amurensis lectin II (MAL II) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were used at 2 to 5 μg/mL and detected with phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). E- and P-selectin-Fc13 were used as described.10 A total of 0.2 μg murine myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG)-Fc and human CD22-Fc (prepared as in14), respectively, were incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated donkey anti-human IgG (0.2 μg; Jackson Immunoresearch) in 50 μL of PBS for 1 hour and added to the cells after 10 minutes of Fc receptor blockage. IL-8 binding to granulocytes was tested by incubating the cells with different concentrations of a fluorescently labeled human IL-8 peptide [K69(CF)]hIL-8(1–77) containing amino acids 1–77 and carboxyfluorescein attached to lysine 6915 in PBS/0.1% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes at 4°C before cells were washed, fixed, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. For control, cells were treated with 100 mU/mL neuraminidase (from Vibrio cholerae; Sigma) for 30 minutes at 37°C in PBS/0.1% bovine serum albumin before they were washed three times and were incubated with IL-8.

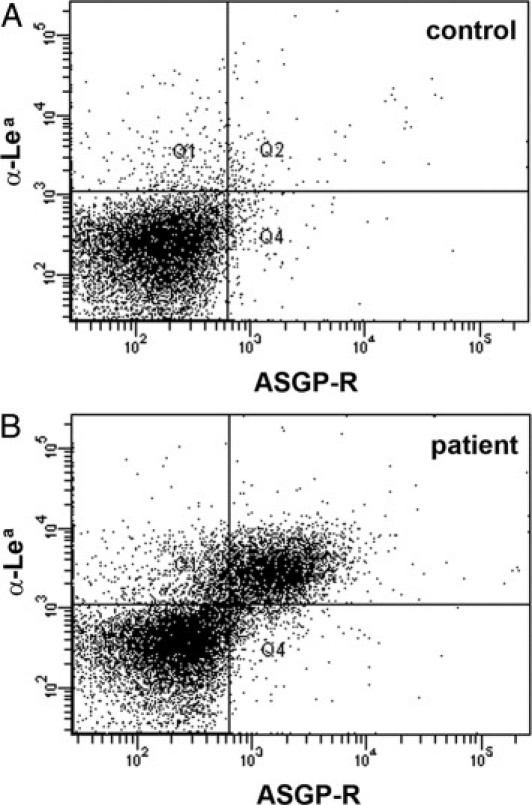

Platelet analysis was done with the following precaution: For comparison of control and patient platelets, we gated on a very small window in the forward scatter/sideward scatter where large normal platelets and small patient platelets overlap in size to exclude size effects. To test for ASGP-R binding, platelets were incubated with 2.5 μg/mL ASGP-R (purified from human liver as described16) for 1 hour at 4°C, washed and incubated with anti-ASGP-R mAb (30201; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). To distinguish patient and donor platelets within the patient samples, the Lea-positive patient received Lea-negative thrombocytes. Patient and donor platelets were distinguished with an anti-Lea antibody (Acris Antibodies). Values obtained by flow cytometry give mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SD from at least three experiments.

Blood-Perfused Flow Chamber Assays

Leukocyte rolling was tested with whole human blood in a blood-perfused flow chamber system17 in which rectangular glass capillaries were coated with 5 μg/mL human E- and 20 μg/mL human P-selectin-Fc proteins (both from R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK), respectively, for 2 hours and then blocked for 1 hour using casein. Slow rolling was obtained by co-immobilizing E- and P-selectin with intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) 3 and 5 μg/mL, respectively). Representative fields of view were recorded for 1 minute using a SW40/0.75 objective and a digital camera (Sensicam QE; Cooke Corporation, Kelheim, Germany). Results were normalized according to the leukocyte numbers of the blood samples.

Isoelectric Focusing of Serum Transferrin and Apolipoprotein C-III

Transferrin was immunoprecipitated from serum and stained.18 Isoelectric focusing was performed with a Phast electrophoresis system using a gel with a pH range of 5 to 7 (Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany). Isofocusing of apolipoprotein C-III (ApoCIII) was performed as described19 using a mixture of pharmalytes (4.2 to 4.9 and 2.5 to 5; GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany), Western blotting with purified anti-ApoCIII Ab (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) and relative quantification of the Enhanced chemiluminescence signal on a Fujifilm Luminescent Image Analyzer (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Fibroblast Transfection

Fibroblasts were transfected with mouse α1,3-fucosyltransferase VII DNA in vector pcDNA320 by nucleofection as described.21

Mutation Analysis and Real-Time PCR of Sialyltransferases

Total RNA (2 μg) was isolated from blood leukocytes (for mutation analysis) or monocytes (for real-time PCR) using a RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was obtained with SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase III (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Sequencing was done using an ABI Prism 3700 capillary sequencer and BigDye 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Quantitative PCR was performed with appropriate primers in an ABI PRISM 7900HT device (Applied Biosystems) using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen). Reactions were performed in reference to housekeeping genes cyclophilin A, hALU, and GAPDH and compared to control cDNA samples from four healthy donors.

Mutation Analysis of the CMP-Sialic Acid Transporter

Genomic DNA was prepared from EDTA-treated whole blood samples of the patient and healthy control donors using the QiaAmp Blood Kit (Qiagen). For generation of cDNA, RNA was prepared from whole blood using the PaxGene Blood RNA Kit (Qiagen) or from fibroblasts using the RNAEasy Kit (Qiagen) and was used directly for PCR. All eight exons of the genomic Slc35a1 sequence were amplified with the following forward and reverse primers binding to flanking intron sequences: exon 1, 5′-GCGGGGAGACGCAGTTTACA-3′, 5′-CACTCCCAGCTAGTGGAGGT-3′; exon 2, 5′-GCAATTGGGGCACTCCCTAG-3′, 5′-GCTTTGCAAGCCAGTCAGTC-3′; exon 3 plus 4, 5′-CACTTGAACACGGGAGGTG-3′, 5′-CCTCTTTGGGGACTGTCATC-3′; exon 5, 5′-GGAGTCTTAAGAGGCAGCAC-3′, 5′-GCCGGACTGAGATGGTCAAG-3′; exon 6 plus intron 6 plus exon 7, 5′-GTCATGTGTCACACAACCTAC-3′, 5′-CTAGCACCCCTCGTCTTAAC-3′; exon 8, 5′-CTTGATTTTACCCGCCCTGC-3′, 5′-GTAGACCCCAAACAGGTCTA-3′. PCR conditions were 5 minutes at 94°C, 35 cycles with 1 minute at 94°C, 1 minute at 67°C, 1.5 minutes at 72°C, and 5 minutes at 72°C. PCR of cDNA was performed with primers 5′-GTACAGTGGAAACCAGCCCA-3′ (bp 499 in NCBI accession No. D87969) and 5′-GTAGACCCCAAACAGGTCTA-3′ (bp 1247) amplifying a fragment of 749 bp starting in exon 4 and ending downstream of the stop codon of Slc35a1 (annealing at 68°C for 2 minutes). PCR products were treated with the PCR product presequencing kit (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH) before they were sequenced as described before.22

Electron Microscopy

Isolated platelets were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer and were processed further for ultrathin cryosectioning and immunogold labeling as described.23

Consent to Patient Studies

Studies on the patient's cells, bone marrow biopsies, and publication of results were done with written consent of the patient's parents and approval by the Ethics Commission of the University of Münster.

Results

A Novel Disorder with Severe Thrombocytopenia and Variable Neutropenia

We detected the novel disease in a girl who developed spontaneous bleeding within the first day of life. The neonate was diagnosed with thrombocytopenia (12,000 to 17,000 platelets/μL blood; normal range: 140,000 to 300,000/μL) and strong initial neutropenia (120 neutrophils/μL blood; normal range: 1250 to 6500/μL). Whereas the severity of the thrombocytopenia remained stable over more than 8 years since the patient's birth, the neutropenia showed considerable variability, with neutrophil numbers ranging from 70 to 5700/μL and a gradual normalization (see Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). At the age of 8 years, the patient shows neutrophil counts of 1200 to 3300/μL and is thus no longer neutropenic. Higher neutrophil counts were recorded during bacterial infections. Despite variable neutropenia, the child never showed signs of immunodeficiency. Counts of lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils were always within the normal range (see Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Starting with day 1 after birth, the thrombocytopenia had to be controlled by weekly platelet transfusions. No further bleeding events were observed under this substitution regime for the 8 years she has been studied. Von Willebrand disease was excluded and no auto- or allo-antibodies against thrombocytes or granulocytes could be detected in the patient. Further details on the phenotype are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Phenotype of the Novel Thrombocytopenic Disorder

| Patient: girl, born in 2002 to nonconsanguineous parents, uneventful pregnancy |

| Normal weight, length, and head circumference |

| Petechial bleedings at trunk and legs, bloody vomiting, and small intracerebral bleeding (I°) 12 hours after birth |

| Initial thrombocytopenia of 12,000 thrombocytes per μL |

| No antibodies against GP IIb/IIIa, Ia/IIa, Ib/IX, and HLA in maternal serum |

| No antibodies on the surface of patient platelets, giving no indication of neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia |

| Abundant megakaryocytes with normal to decreased size and normal neutrophil precursor cells in bone marrow biopsies |

| Enlarged thrombocytes of heterogenous size with giant thrombocytes nearly as large as erythrocytes in peripheral blood |

| Neutrophil counts below 1000 per μL at 4 weeks of age and below 500 per μL on several occasions thereafter |

| No antibodies against granulocytes detectable |

| Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia unresponsive to corticosteroid treatment for 2 weeks and to immunoglobulin treatment |

| No further bleeding complications due to weekly thrombocyte transfusions |

| Thrombocyte counts constantly below 10,000 per μL upon admission |

| Despite neutropenia no increased frequency of infections |

| No splenomegaly |

| Normal psychomotor development |

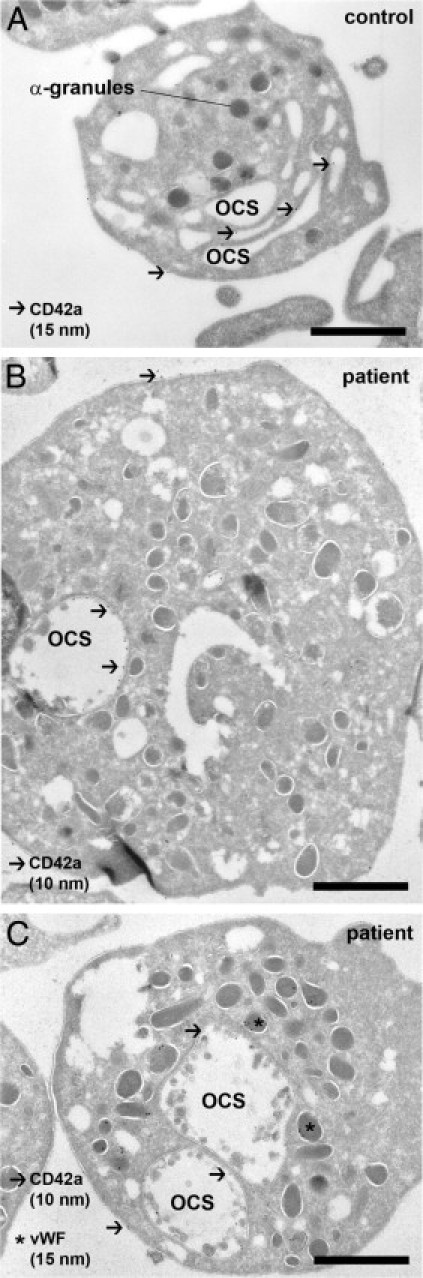

Giant Platelets with Ultrastructural Abnormalities

Flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood cells revealed the presence of normal-sized thrombocytes as well as of giant platelets. This was confirmed by electron microscopy (Figure 1). The enlarged platelets had a mean diameter of 5.0 μm with a range of 3.5 to 6.3 μm (control platelets mean: 2.5 μm, range: 1.8 to 2.8 μm) and a calculated mean volume of 65 fL with a range of 30 to 80 fL (control platelets: 8 fL, range: 5 to 12 fL).

Figure 1.

Platelets are enlarged and show changes of the open canalicular membrane system. A: Typical appearance of a normal resting human platelet in an ultrathin cryosection. The cell has a round shape, and α-granules are filled with secretory cargo. The open canalicular membrane (OCS) is continuous with the plasma membrane and appears as a cluster of segmented channels, positively identified by an anti-CD42a mAb and 15 nm protein A gold (arrows). B and C show representative patient platelets at the same magnification. The diameter of the platelets is increased, and the OCS, labeled for CD42a, is condensed to one or two large saccular compartments. The round shape of the platelets and the presence of von Willebrand factor (vWF) in α-granules show that the platelets are quiescent. Bound anti-CD42a mAb was detected with 10-nm protein A gold (arrows), and anti-VWF Ab with 15-nm protein A gold (asterisks). Scale bar = 1 μm.

Ultrastructural analysis showed striking abnormalities of the platelets' open canalicular membrane system (OCS). Here, the multiple segmented channels that form the OCS in normal platelets (Figure 1A) were replaced by one or two large saccular compartments (Figure 1, B and C), strongly indicating a defect in platelet formation. The micrographs also show sphere-like structures within the OCS of the patient platelets, but not of control platelets. Some of these structures appear to be surrounded by membranes. Abnormal membrane blebbing of the OCS may be an explanation for this phenomenon. Bone marrow examination on three separate occasions showed that erythroid and granulocytic maturation were largely normal with a marginal left shift. Interestingly, megakaryocytic hyperplasia with an increased number of micromegakaryocytes was found (not shown).

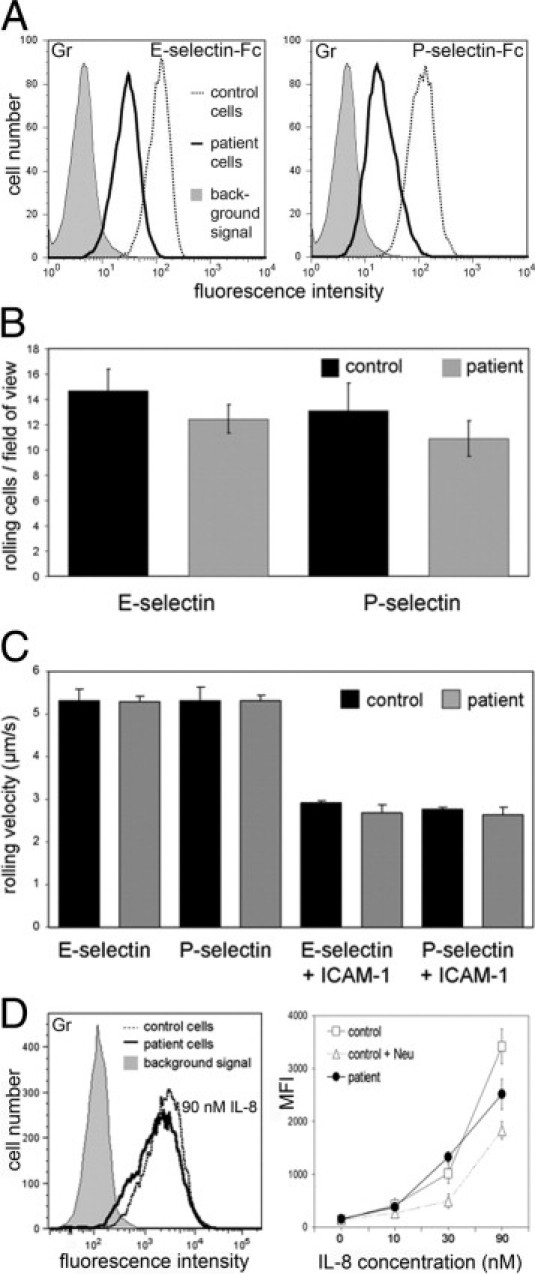

Binding of Selectins and IL-8 to Granulocytes

To analyze the molecular cause for this disease, we turned to granulocytes that were obviously also affected but considerably easier to obtain from the patient than platelets. When we analyzed the expression of adhesion molecules in patient granulocytes, we noticed that binding of soluble E- and P-selectin-Fc fusion proteins was reduced by 70% ± 14% and 76% ± 15%, respectively [mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values ± SD from five independent flow cytometry experiments] (Figure 2A). This defect, however, was not as strong as in leukocyte adhesion deficiency II, where the expression of functional selectin ligands and leukocyte rolling on selectins are virtually absent.10,24 Indeed, the number of patient and control leukocytes rolling on immobilized E- and P-selectin in flow chamber assays showed no significant difference (Figure 2B). Moreover, the velocities of cells rolling on selectins or on selectins plus intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (slow rolling) were identical for patient and control leukocytes (Figure 2C). These data suggest that the residual selectin ligands that we detected in patient cells are sufficient to preserve selectin-mediated interactions. Finally, we tested binding of interleukin-8 (IL-8) to granulocytes since the interaction of this leukocyte arrest-mediating chemokine was found to be reduced in mice deficient for α2,3-sialyltransferase IV and in human cells treated with neuraminidase.25 Figure 2D shows that binding of human IL-8 to patient granulocytes over a concentration range of 10 to 90 nmol/L was only marginally reduced (MFI: 84% ± 29% of control values, n = 9). In fact, only at the highest IL-8 concentration a reduction was detected (an example is shown in the Figure 2D). Taken together, the data on selectin-mediated rolling and IL-8 binding are consistent with the finding that the patient shows normal immunity.

Figure 2.

Hyposialylation only marginally affects binding of selectins and IL-8. A: Binding of E- and P-selectin-Fc chimeric proteins to granulocytes. Background signals were obtained with VE-cadherin-Fc and were virtually identical in control and patient cells. The latter are shown. Results are representative for three experiments. B: Leukocyte rolling on endothelial selectins. The number of rolling leukocytes in whole blood on immobilized E- and P-selectin was assessed in a blood-perfused flow chamber. Nine fields of view were analyzed in each sample. Data are from three independent experiments. C: Rolling velocities. Leukocytes were analyzed as in B. Additionally, slow rolling on selectins co-immobilized with ICAM-1 was analyzed. Data are from three independent experiments. D: Binding of human IL-8 to granulocytes. Cells were incubated with a fluorescently labeled human IL-8 peptide. As control, cells were incubated with neuraminidase from Vibrio cholerae. Neuraminidase treatment reduced IL-8 binding only partially as has been shown before.25 The left panel shows representative histograms. Data in the right panel are from three independent experiments.

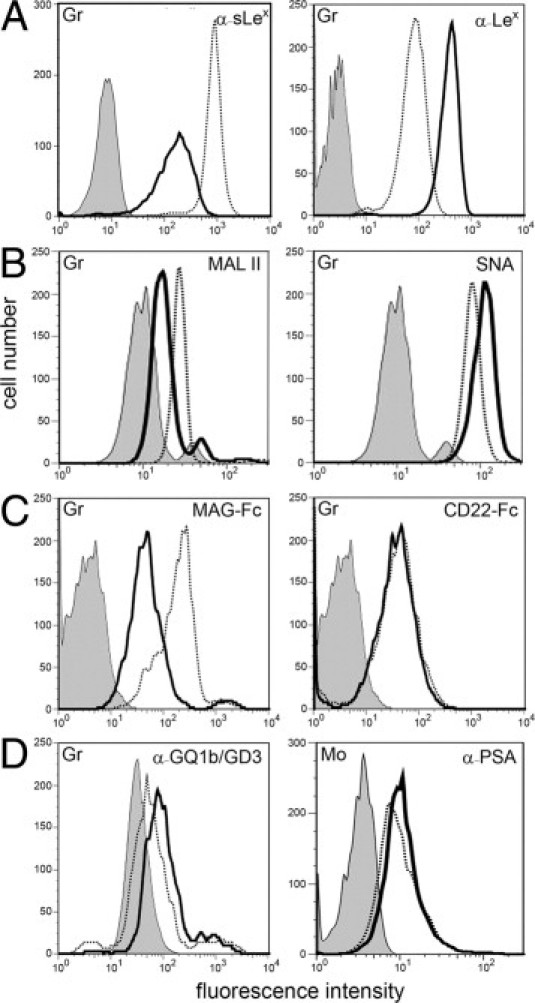

Myeloid Cells and Platelets Display a Defect in α2,3-Sialylation

Selectin ligands carry fucosylated and sialylated glycostructures that are identical with or similar to sialyl-Lewis X (sLex) and are required for selectin binding. We found that patient granulocytes exhibited strongly reduced surface expression of sLex (19% ± 9% of control MFI, n = 8) and increased expression of its nonsialylated form Lex (463% ± 96% of control MFI, n = 8) (Figure 3A). Similar results were obtained for blood monocytes (not shown).

Figure 3.

Myeloid cells display a defect in α2,3-sialylation. Granulocytes (Gr) were tested for binding of the following reagents: mAbs against sLex and Lex (A), Maackia amurensis lectin II (MAL II, binds preferentially to α2,3-sialylated structures) and Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA, binds preferentially to α2,6-sialylated structures) (B), myelin-associated glycoprotein-Fc chimera (MAG-Fc, Siglec-4-Fc; binds to α2,3-sialylated structures) and CD22-Fc (Siglec-2-Fc; binds to α2,6-sialylated structures) (C), and a mAb that detects α2,8-sialylated gangliosides GQ1b and GD3 (D, left panel). Binding of a mAb specific for α2,8-sialylated polysialic acid (PSA) to monocytes (Mo) is show in D (right panel). Background signals were obtained with isotype control mAbs (for mAbs), secondary reagent only (for lectins), and VE-cadherin-Fc (for Fc-constructs). Background signals in control and patient cells were virtually identical. The latter are shown. Results are representative for at least three experiments per panel.

We then studied lectin binding to granulocytes and found normal binding of concanavalin A and AAL, which are specific for α-linked mannose and fucose, respectively (not shown). However, the cells showed increased binding of peanut agglutinin (PNA) which binds to the nonsialylated, but not to the sialylated, form of the T antigen (galactosyl-β1,3-N-acetylgalactosamine), suggesting a defect in T antigen sialylation (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). More interestingly, we found that binding of Maackia amurensis lectin II (MAL II), which preferentially recognizes sialic acid linked to galactose in α2,3-linkage, was reduced (Figure 3B). In contrast, binding of SNA, which preferentially recognizes α2,6-linked sialic acid, was normal (Figure 3B). Together with the reduced expression of the α2,3-sialylated sLex, these data strongly suggested a partial α2,3-sialylation defect.

Hypo-α2,3-sialylation in granulocytes was confirmed by reduced binding of recombinant myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG/Siglec-4), which is specific for α2,3-linked sialic acid, whereas binding of α2,6-sialylation-specific CD22 (Siglec-2) was normal (Figure 3C). This pattern of defective α2,3-sialylation and normal α2,6-sialylation was also found in peripheral blood monocytes (not shown). In control lymphocytes, Lex and sLex were hardly detectable, but MAL II and MAG readily bound and gave equal signals in control and patient cells, showing that the defect in α2,3-sialylation is not present in these cells (data not shown). As skin fibroblasts are devoid of sLex, we transfected them with a plasmid containing the cDNA sequence coding for α1,3-fucosyltransferase VII. This led to virtually equal expression of sLex in healthy and patient fibroblasts (not shown), demonstrating that skin fibroblasts are not affected by the disease and that the defect is cell-specific.

In contrast to α2,3-sialylation, the third type of sialic acid linkage, α2,8-sialylation, was found to be normal in granulocytes as judged by normal binding of mAb CGM3, which reacts with the α2,8-sialylated gangliosides GQ1b and GD3 (Figure 3D). Binding of mAb 735, which is specific for α2,8-sialylated polysialic acid, bound very weakly to control granulocytes (not shown). However, it showed detectable and equal binding to control and patient monocytes (Figure 3D), further excluding a defect in α2,8-sialylation.

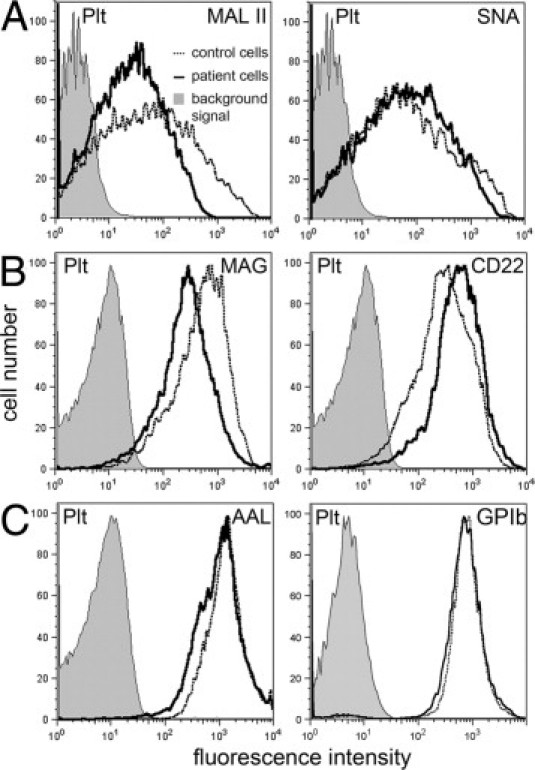

Flow cytometry analysis of control and patient thrombocytes showed that E- and P-selectin as well as antibodies against sLex, Lex, GQ1b/GD3, and polysialic acid did not bind to these cells. However, we found that, as in granulocytes, binding of α2,3-sialylation–specific MAL II and MAG, but not of α2,6-sialylation–specific SNA and CD22, to patient platelets was reduced (Figure 4, A and B). Binding of fucose-specific AAL was normal (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Defect in α2,3-sialylation but normal GPIb expression in platelets. Platelets (Plt) were tested for binding of the following reagents: Maackia amurensis lectin II (MAL II) and Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA) (A), myelin-associated glycoprotein-Fc (MAG-Fc, Siglec-4-Fc) and CD22-Fc (Siglec-2-Fc) chimeras (B), Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) (C; left panel), and a GPIb mAb (C; right panel). Background signals were obtained with isotype control mAbs (for mAbs), secondary reagent only (for lectins), and VE-cadherin-Fc (for Fc-constructs). Histograms were obtained from a very small window in the forward scatter/sideward scatter plot where large normal platelets and small patient platelets overlap in size to exclude size effects. Results are representative for at least three experiments per panel.

Changes in the sialylation patterns of serum transferrin and/or apolipoprotein C-III had been shown for all types of CDG-I as well as CDG-IIa, -d, -e, -f.26 However, isoelectric focusing of the patient's serum transferrin and apolipoprotein C-III revealed normal sialylation (Figure 5 and Table 2). In addition, defects in the generation of the lipid-linked oligosaccharide (LLO), which are indicative of CDG-I, were excluded by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis (see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Taken together, these data show that the novel disease is characterized, not by a general sialylation deficiency, but rather by a specific defect in α2,3-sialylation in a restricted set of cells.

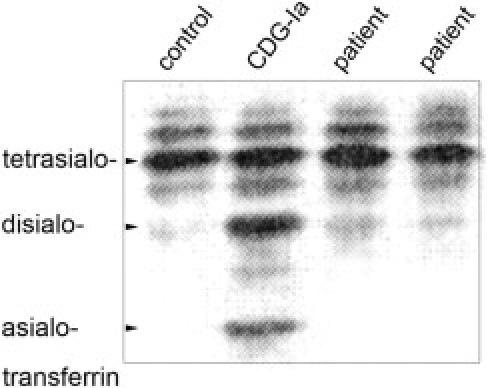

Figure 5.

Normal sialylation of serum transferrin. Isoelectric focusing of serum transferrin. Two independently collected serum samples of the patient described in this report, a sample of a CDG-Ia patient and of an age- and sex-matched healthy control person were subjected to IEF. Unlike the CDG-Ia sample, the patient samples show normal distribution of tetra- and disialylated forms of transferrin. One of three experiments is shown.

Table 2.

Isoelectric Focusing of Apolipoprotein CIII

| Percentage of ApoCIII isoforms⁎ | ApoCIII-0 (%) | ApoCIII-1 (%) | ApoCIII-2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient, sample 1 | 5.3 | 68.4 | 26.4 |

| Patient, sample 2 | 6.5 | 60.4 | 33.2 |

| Patient, sample 3 | 9.7 | 56.5 | 33.7 |

| CDG-IIf patient | 6.0 | 78.0 | 16.0 |

| Reference range (age: 1–18 yr) | 0–11.6 | 33.1–66.9 | 27.4–60.0 |

| Patient's mother | 8.1 | 59.5 | 32.4 |

| Reference range (age: >18 yr) | 2.6–18.9 | 42.9–69.2 | 23.2–50.0 |

Three independently collected serum samples of the patient and samples of the patient's mother were subjected to isoelectrical focusing. Results obtained for a CDG-IIf patient26 are shown for comparison. The samples of the patient and her mother show isoform distributions that are within the respective reference ranges, whereas the CDG-IIf results indicate hyposialylation of ApoCIII as seen from the shift of disialylated ApoCIII-2 to monosialylated ApoCIII-1.

No Functional Mutations in the Gene Coding for the CMP-Sialic Acid Transporter

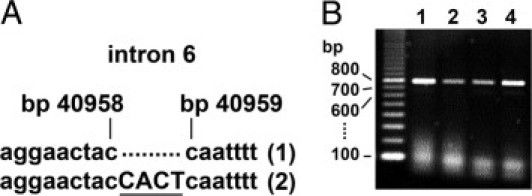

We performed a large number of experiments in search for the genetic defect causing this disease. We reasoned that with impaired α2,3-sialylation and reduced sLex expression, an α2,3-sialyltransferase (ST3-Gal) may be defective. Three α2,3-sialyltransferases (ST3-Gal III, IV, VI) can potentially generate sLex.27,28 We sequenced exon sequences with flanking intron regions of the enzymes' genomic DNA obtained from patient monocytes. No mutations were detected (not shown). We also performed real-time PCR and found that mRNA expression levels of the three sialyltransferases in patient monocytes were completely normal (not shown). As the disease described here shows similarities with CDG-IIf, we also analyzed the gene coding for the CMP-sialic acid transporter (SLC35A1). We sequenced all eight exons of the Slc35a1 gene in genomic DNA obtained from peripheral leukocytes of the patient but found no mutations. Sequencing of intron 6 revealed that the patient was heterozygous for an insertion of four nucleotides (CACT) between bp 40958 and 40959 (NCBI accession number NG_016207.1) (Figure 6A and see Supplemental Figure S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The same insertion had been found in the mother of the CDG-IIf patient. It was predicted to cause one of the two mutations found in the CDG-IIf patient, a 130-bp deletion in exon 6, by modifying the splicing of this exon.4 However, analysis of cDNA of our patient by PCR that covered exons 5 to 8 led to PCR products with the expected normal length of 749 bp (Figure 6B), and cDNA sequencing confirmed that no deletions of the Slc35a1 coding sequence were present (see Supplemental Figure S4 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Finally, we searched for the CACT insertion in genomic DNA samples of 51 healthy individuals and found that 19 samples were heterozygous and 6 were homozygous for this mutation. This demonstrates that the insertion in intron 6 of the Slc35a1 gene represents a silent polymorphism. Taken together, these data exclude the presence of a genetic defect of the CMP-sialic acid transporter, leaving the genetic cause of this disease unknown. Platelet glycoprotein GPIb is reduced in CDG-IIf and is reduced or absent in Bernard-Soulier syndrome.3,29,30 In contrast to this, the patient's platelets showed normal GPIb expression (Figure 4C), further excluding the presence of one of the above-mentioned diseases.

Figure 6.

Analysis of the gene coding for the CMP-sialic acid transporter SLC35A1. A: Genomic DNA was prepared from peripheral blood leukocytes of the patient and amplified by PCR. Sequencing results of a fragment containing intron 6 are shown. One allele (1) was found to be normal, the other (2) to contain a CACT insertion between bp 40958 and 40959 (NCBI accession number NG_016207.1). B: Patient (lanes 1, 3) and control (lanes 2, 4) cDNA from blood leukocytes (lanes 1, 2) and fibroblasts (lanes 3, 4) were amplified by PCR covering exons 5 to 8. All PCR products show the expected normal length of 749 bp.

Abnormal Interaction of Platelets with the Liver Asialoglycoprotein Receptor

Recently, the liver ASGP-R was shown to remove hypo-α2,3-sialylated thrombocytes from the circulation in mice.8,9 We therefore analyzed binding of ASGP-R protein purified from human liver to control and patient platelets. Figure 7A shows that the ASGP-R did not bind to control platelets. Thrombocytes of the Lea-positive patient who received platelet transfusions of Lea-negative donors are depicted in Figure 7B. The figure shows that whereas the ASGP-R protein did not interact with donor platelets, it reacted with virtually all patient platelets. This result suggests that increased platelet binding to the ASGP-R may contribute to the thrombocytopenia in this novel disease.

Figure 7.

Anomalous platelet interaction with the liver asialoglycoprotein receptor. Platelets were incubated with native purified asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGP-R) protein before cells were incubated with anti-ASGP-R mAb and counterstained with anti-Lewisa (Lea) mAb. A: Platelets of a Lea-negative control person are shown. B: Platelets of the Lea-positive patient who received platelet transfusions of Lea-negative donors are shown. Only the patient's platelets, but not the donor platelets, bind to ASPG-R protein. Results are representative for at least three experiments per panel.

Discussion

Our results show that the disease described here is different from known disorders with macrothrombocytopenia. The new sialylation disorder is most similar to CDG-IIf but differs from it in that it shows no alterations of GPIb expression and apolipoprotein C-III glycosylation and lacks mutations of the gene coding for the CMP-sialic acid transporter. The small CATC insert in intron 6 that had been found in the mother of the CDG-IIf patient4 was also found in the new patient but turned out to be a silent polymorphism.

Interestingly, the glycosylation defect described here is restricted to α2,3-sialylation, resulting in reduced expression of sLex, as well as of ligands for selectins, for MAG and MAL II. This is reminiscent of the phenotype of mice deficient in ST3-Gal IV.6,7 These mice show reduced selectin binding to granulocytes and a macrothrombocytopenia that can be counteracted by ASGP-R-blocking asialofetuin, but no neutropenia. Additionally, these mice show reduced serum levels of von Willebrand factor, which we did not observe in the human disease described here. Despite the similarities between the novel disease and the phenotype of ST3-Gal IV−/− mice, we found no mutations and normal gene expression of ST3-Gal IV and two further sialyltransferases that are implicated in the generation of sLex. Thus, the exact molecular cause for this disease remains speculative. One possibility is that ST3-Gal expression is blocked at the translational level. To analyze ST3-Gal protein levels, we tested a ST3-Gal IV–specific antibody (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) which, however, did not give specific signals in a variety of assays including Western blotting and immunofluorescence. To our knowledge, no further antibodies against human ST3-Gal proteins are available. Another possibility is that an unknown cofactor that may be required for sialyltransferase activity is defective. However, we were unable to devise an assay that can detect changes in linkage-specific sialyltransferase activity in the low number of affected cells that are available from the patient.

The sialylation defect in this disease is cell-specific. As in ST3-Gal IV−/− mice, granulocytes and platelets are affected. In addition, we show that monocytes are defective, whereas lymphocytes and skin fibroblasts are not. This might reflect the expression profile of an ST3-Gal or a cofactor if such proteins are affected in the way described above.

The defect in α2,3-sialylation appears to have an effect on the generation of platelets. We detected an increased number of micromegakaryocytes, indicating defective megakaryocytopoiesis. In addition, patient platelets were enlarged and showed abnormalities of the OCS structure. Furthermore, sphere-like structures were visible within the OCS that may be the result of abnormal membrane blebbing. It is unclear whether this is directly caused by hyposialylation, although alterations in the demarcation process in megakaryocytes have been observed in the sialylation deficiency CDG-IIf,3 suggesting that hyposialylation can indeed interfere with membrane formation processes.

How sialylation can influence platelet generation in the bone marrow is not known. Repulsion by the negative charge of sialic acid may be required for a correct demarcation process. On the other hand, interactions of megakaryocytes with E-selectin in the bone marrow appear to be important for megakaryocyte migration,31 and P-selectin–deficient mice show enhanced megakaryocytopoiesis.32 Thus, reduced selectin interactions with hyposialylated ligands might contribute to defective platelet generation.

Desialylation of platelets results in their clearance from the circulation.5 Recently, removal of desialylated platelets by liver ASGP-R was found to be a major cause for this phenomenon.8,9 Consistent with this, we found that patient platelets showed increased binding to the liver ASGP-R. It is tempting to speculate, but also difficult to prove in patients, that such receptors are at least in part responsible for the thrombocytopenia in the new disease.

We have previously found that the defect in fucosylation in CDG-IIc can be corrected with oral l-fucose supplementation.10,33 N-acetyl-mannosamine (ManNAc) was described as a sialic acid precursor that can be taken up, metabolized to sialic acid and incorporated into the plasma membrane of mammalian cells.34,35 We therefore extensively investigated the effect of exogenous ManNAc (in concentrations ranging from 2 to 50 mmol/L) on sLex expression in cultures of patient granulocytes and monocytes using incubation times of 12 to 72 hours. In neither case did the sialic acid precursor increase sLex expression (not shown). Thus, thrombocyte transfusion remains the most effective therapy for this novel human sialylation defect.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ingrid Du Chesne, Marie-Luise Többens (Universitätsklinikum Münster), Martin Stehling and Ute Ipe (the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine, Münster) for excellent technical assistance; Paul Crocker (University of Dundee, United Kingdom) for recombinant MAG and CD22 proteins; Rita Gerardy-Schahn (Medical High School, Hannover, Germany) for antibodies; and Heiko Gäthje and Nadine Bock (University of Bremen, Germany) and Karoline Nordsieck (University of Leipzig, Germany) for producing Fc constructs and recombinant IL-8, respectively. We thank the Consortium for Functional Glycomics for their support in Glycan analysis, and Carlos Hirschberg (Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine, MA) for measuring CMP-sialic acid transport activity in fibroblasts. Above all, we thank the patient for her patience with us.

Footnotes

Supported by the Max Planck Society (M.K.W. and C.J.), by BMBF and IMF (J.D., T.St., and T.M.), by DFG (AZ428/3-1 to A.Z.), and by Volkswagenstiftung, HFSP and BMBF (S.K. and K.S.).

T.M. and M.K.W. contributed equally as senior authors of this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.012.

Contributor Information

Thorsten Marquardt, Email: marquat@uni-muenster.de.

Martin K. Wild, Email: mwild@mpi-muenster.mpg.de.

Supplementary data

Binding of peanut agglutinin (PNA) to granulocytes. Control and patient cells were incubated with PNA and secondary reagent (PNA) or with secondary reagent only (co) before they were analyzed by flow cytometry. Patient cells exhibit increased PNA binding.

Expression of lipid-linked oligosaccharides (LLO). Radioactively labeled LLO structures from healthy control and patient fibroblasts were extracted and subjected to high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The elution time of the main peak (G3) in both, control and patient samples, is consistent with full length oligosaccharides of the structure Glc3Man9GlcNAc2. For analysis the fibroblasts were labeled for 45 min with 100 μCi [2-3H]-mannose, were chased for 10 min in MEM medium, and subsequently washed with PBS. Dolichylpyrophosphate-linked oligosaccharides were extracted as described (Kranz et al., (2001). J Clin. Invest. 108:1613–1619). HPLC was performed in an acetonitril/water gradient using a Microsorb MV column (Varian GmbH) with a Waters Alliance system (Waters GmbH).

Analysis of the gene coding for the CMP-sialic acid transporter SLC35A1. (A, B) Genomic DNA was prepared from peripheral blood leukocytes of the patient and amplified by PCR. Sequencing results of a fragment containing intron 6 are shown. One allele (1) was found to be normal, the other (2) to contain a CACT insertion between bp 40958 and 40959 (NCBI accession number NG_016207.1). Note that results were obtained from reverse Sequencing. (C) Patient (1,3) and control (2,4) cDNA from blood leukocytes (1,2) and fibroblasts (3,4) were amplified by PCR covering exons 5 to 8. All PCR products show the expected normal length of 749 bp.

Sequence analysis of exon 6 of the gene coding for the CMP-sialic acid transporter. Sequencing was performed on cDNA obtained from patient leukocyte mRNA. The sequence of exon 6 is complete and shows no mutations. Exon boundaries are underlined and correspond to positions 40496 and 40672 in NCBI sequence NG_016207.1.

References

- 1.Kunishima S., Kamiya T., Saito H. Genetic abnormalities of Bernard-Soulier syndrome. Int J Hematol. 2002;76:319–327. doi: 10.1007/BF02982690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seri M., Cusano R., Gangarossa S., Caridi G., Bordo D., Lo Nigro C., Ghiggeri G.M., Ravazzolo R., Savino M., Del Vecchio M., D'Apolito M., Iolascon A., Zelante L.L., Savoia A., Balduini C.L., Noris P., Magrini U., Belletti S., Heath K.E., Babcock M., Glucksman M.J., Aliprandis E., Bizzaro N., Desnick R.J., Martignetti J.A. Mutations in MYH9 result in the May-Hegglin anomaly, and Fechtner and Sebastian syndromes: The May-Heggllin/Fechtner Syndrome Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;26:103–105. doi: 10.1038/79063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willig T.B., Breton-Gorius J., Elbim C., Mignotte V., Kaplan C., Mollicone R., Pasquier C., Filipe A., Mielot F., Cartron J.P., Gougerot-Pocidalo M.A., Debili N., Guichard J., Dommergues J.P., Mohandas N., Tchernia G. Macrothrombocytopenia with abnormal demarcation membranes in megakaryocytes and neutropenia with a complete lack of sialyl-Lewis-X antigen in leukocytes–a new syndrome? Blood. 2001;97:826–828. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez-Duncker I., Dupre T., Piller V., Piller F., Candelier J.J., Trichet C., Tchernia G., Oriol R., Mollicone R. Genetic complementation reveals a novel human congenital disorder of glycosylation of type II, due to inactivation of the Golgi CMP-sialic acid transporter. Blood. 2005;105:2671–2676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg J., Packham M.A., Cazenave J.P., Reimers H.J., Mustard J.F. Effects on platelet function of removal of platelet sialic acid by neuraminidase. Lab Invest. 1975;32:476–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellies L.G., Ditto D., Levy G.G., Wahrenbrock M., Ginsburg D., Varki A., Le D.T., Marth J.D. Sialyltransferase ST3Gal-IV operates as a dominant modifier of hemostasis by concealing asialoglycoprotein receptor ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10042–10047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142005099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellies L.G., Sperandio M., Underhill G.H., Yousif J., Smith M., Priatel J.J., Kansas G.S., Ley K., Marth J.D. Sialyltransferase specificity in selectin ligand formation. Blood. 2002;100:3618–3625. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grewal P.K., Uchiyama S., Ditto D., Varki N., Le D.T., Nizet V., Marth J.D. The Ashwell receptor mitigates the lethal coagulopathy of sepsis. Nat Med. 2008;14:648–655. doi: 10.1038/nm1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorensen A.L., Rumjantseva V., Nayeb-Hashemi S., Clausen H., Hartwig J.H., Wandall H.H., Hoffmeister K.M. Role of sialic acid for platelet life span: exposure of beta-galactose results in the rapid clearance of platelets from the circulation by asialoglycoprotein receptor-expressing liver macrophages and hepatocytes. Blood. 2009;114:1645–1654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marquardt T., Lühn K., Srikrishna G., Freeze H.H., Harms E., Vestweber D. Correction of leukocyte adhesion deficiency type II with oral fucose. Blood. 1999;94:3976–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pukel C.S., Lloyd K.O., Travassos L.R., Dippold W.G., Oettgen H.F., Old L.J. GD3, a prominent ganglioside of human melanoma: Detection and characterisation by mouse monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1133–1147. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frosch M., Görgen I., Boulnois G.J., Timmis K.N., Bitter-Suermann D. NZB mouse system for production of monoclonal antibodies to weak bacterial antigens: isolation of an IgG antibody to the polysaccharide capsules of Escherichia coli K1 and group B meningococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:1194–1198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahne M., Jager U., Isenmann S., Hallmann R., Vestweber D. Five tumor necrosis factor-inducible cell adhesion mechanisms on the surface of mouse endothelioma cells mediate the binding of leukocytes. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:655–664. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.3.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelm S., Pelz A., Schauer R., Filbin M.T., Tang S., de Bellard M.E., Schnaar R.L., Mahoney J.A., Hartnell A., Bradfield P., Crocker P.R. Sialoadhesin, myelin-associated glycoprotein and CD22 define a new family of sialic acid-dependent adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Curr Biol. 1994;4:965–972. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.David R., Machova Z., Beck-Sickinger A.G. Semisynthesis and application of carboxyfluorescein-labelled biologically active human interleukin-8. Biol Chem. 2003;384:1619–1630. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treichel U., Schreiter T., Meyer zum Buschenfelde K.H., Stockert R.J. High-yield purification and characterization of human asialoglycoprotein receptor. Protein Expr Purif. 1995;6:251–255. doi: 10.1006/prep.1995.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuwano Y., Spelten O., Zhang H., Ley K., Zarbock A. Rolling on E- or P-selectin induces the extended but not high-affinity conformation of LFA-1 in neutrophils. Blood. 2010;116:617–624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niehues R., Hasilik M., Alton G., Korner C., Schiebe-Sukumar M., Koch H.G., Zimmer K.P., Wu R., Harms E., Reiter K., von Figura K., Freeze H.H., Harms H.K., Marquardt T. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type Ib: Phosphomannose isomerase deficiency and mannose therapy. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1414–1420. doi: 10.1172/JCI2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wopereis S., Grunewald S., Morava E., Penzien J.M., Briones P., Garcia-Silva M.T., Demacker P.N., Huijben K.M., Wevers R.A. Apolipoprotein C-III isofocusing in the diagnosis of genetic defects in O-glycan biosynthesis. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1839–1845. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.022541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang M.C., Laskowska A., Vestweber D., Wild M.K. The alpha (1,3)-fucosyltransferase Fuc-TIV, but not Fuc-TVII, generates sialyl Lewis X-like epitopes preferentially on glycolipids. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47786–47795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helmus Y., Denecke J., Yakubenia S., Robinson P., Luhn K., Watson D.L., McGrogan P.J., Vestweber D., Marquardt T., Wild M.K. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency II patients with a dual defect of the GDP-fucose transporter. Blood. 2006;107:3959–3966. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kranz C., Jungeblut C., Denecke J., Erlekotte A., Sohlbach C., Debus V., Kehl H.G., Harms E., Reith A., Reichel S., Grobe H., Hammersen G., Schwarzer U., Marquardt T. A defect in dolichol phosphate biosynthesis causes a new inherited disorder with death in early infancy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:433–440. doi: 10.1086/512130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slot J.W., Geuze H.J. Cryosectioning and immunolabeling. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2480–2491. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Etzioni A., Frydman M., Pollack S., Avidor I., Phillips M.L., Paulson J.C., Gershoni-Baruch R. Brief report: recurrent severe infections caused by a novel leukocyte adhesion deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1789–1792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212173272505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frommhold D., Ludwig A., Bixel M.G., Zarbock A., Babushkina I., Weissinger M., Cauwenberghs S., Ellies L.G., Marth J.D., Beck-Sickinger A.G., Sixt M., Lange-Sperandio B., Zernecke A., Brandt E., Weber C., Vestweber D., Ley K., Sperandio M. Sialyltransferase ST3Gal-IV controls CXCR2-mediated firm leukocyte arrest during inflammation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1435–1446. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wopereis S., Grunewald S., Huijben K.M., Morava E., Mollicone R., van Engelen B.G., Lefeber D.J., Wevers R.A. Transferrin and apolipoprotein C-III isofocusing are complementary in the diagnosis of N- and O-glycan biosynthesis defects. Clin Chem. 2007;53:180–187. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.073940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okajima T., Fukumoto S., Miyazaki H., Ishida H., Kiso M., Furukawa K., Urano T. Molecular cloning of a novel alpha2,3-sialyltransferase (ST3Gal VI) that sialylates type II lactosamine structures on glycoproteins and glycolipids. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11479–11486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki K., Watanabe E., Kawashima K., Sekine S., Dohi T., Oshima M., Hanai N., Nishi T., Hasegawa M. Expression cloning of a novel Gal beta (1–3/1–4) GlcNAc alpha 2,3-sialyltransferase using lectin resistance selection. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22782–22787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins C.S., Phillips D.R., Clemetson K.J., Meyer D., Larrieu M.J., Luscher E.F. Platelet membrane glycoproteins implicated in ristocetin-induced aggregation: Studies of the proteins on platelets from patients with Bernard-Soulier syndrome and von Willebrand's disease. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:112–124. doi: 10.1172/JCI108251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nurden A.T., Caen J.P. Specific roles for platelet surface glycoproteins in platelet function. Nature. 1975;255:720–722. doi: 10.1038/255720a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamada T., Mohle R., Hesselgesser J., Hoxie J., Nachman R.L., Moore M.A., Rafii S. Transendothelial migration of megakaryocytes in response to stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) enhances platelet formation. J Exp Med. 1998;188:539–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banu N., Avraham S., Avraham H.K. P-selectin, and not E-selectin, negatively regulates murine megakaryocytopoiesis. J Immunol. 2002;169:4579–4585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lühn K., Marquardt T., Harms E., Vestweber D. Discontinuation of fucose therapy in LADII causes rapid loss of selectin ligands and rise of leukocyte counts. Blood. 2001;97:330–332. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu X., Wang D.I. Improvement of interferon-gamma sialylation in Chinese hamster ovary cell culture by feeding of N-acetylmannosamine. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;58:642–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kayser H., Zeitler R., Kannicht C., Grunow D., Nuck R., Reutter W. Biosynthesis of a nonphysiological sialic acid in different rat organs, using N-propanoyl-D-hexosamines as precursors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16934–16938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Binding of peanut agglutinin (PNA) to granulocytes. Control and patient cells were incubated with PNA and secondary reagent (PNA) or with secondary reagent only (co) before they were analyzed by flow cytometry. Patient cells exhibit increased PNA binding.

Expression of lipid-linked oligosaccharides (LLO). Radioactively labeled LLO structures from healthy control and patient fibroblasts were extracted and subjected to high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The elution time of the main peak (G3) in both, control and patient samples, is consistent with full length oligosaccharides of the structure Glc3Man9GlcNAc2. For analysis the fibroblasts were labeled for 45 min with 100 μCi [2-3H]-mannose, were chased for 10 min in MEM medium, and subsequently washed with PBS. Dolichylpyrophosphate-linked oligosaccharides were extracted as described (Kranz et al., (2001). J Clin. Invest. 108:1613–1619). HPLC was performed in an acetonitril/water gradient using a Microsorb MV column (Varian GmbH) with a Waters Alliance system (Waters GmbH).

Analysis of the gene coding for the CMP-sialic acid transporter SLC35A1. (A, B) Genomic DNA was prepared from peripheral blood leukocytes of the patient and amplified by PCR. Sequencing results of a fragment containing intron 6 are shown. One allele (1) was found to be normal, the other (2) to contain a CACT insertion between bp 40958 and 40959 (NCBI accession number NG_016207.1). Note that results were obtained from reverse Sequencing. (C) Patient (1,3) and control (2,4) cDNA from blood leukocytes (1,2) and fibroblasts (3,4) were amplified by PCR covering exons 5 to 8. All PCR products show the expected normal length of 749 bp.

Sequence analysis of exon 6 of the gene coding for the CMP-sialic acid transporter. Sequencing was performed on cDNA obtained from patient leukocyte mRNA. The sequence of exon 6 is complete and shows no mutations. Exon boundaries are underlined and correspond to positions 40496 and 40672 in NCBI sequence NG_016207.1.