Abstract

Clostridium septicum (C. septicum) gas gangrene is well documented in the literature, typically in the setting of trauma or immunosuppression. In this paper, we report a unique case of spontaneous clostridial myonecrosis in a patient with Crohn’s disease and sulfasalazine-induced neutropenia. The patient presented with left thigh pain, vomiting and diarrhea. Blood tests demonstrated a profound neutropenia, and magnetic resonance imaging of the thigh confirmed extensive myonecrosis. The patient underwent emergency hip disarticulation, followed by hemicolectomy. C. septicum was cultured from the blood. Following completion of antibiotic therapy, the patient developed myonecrosis of the right pectoral muscle necessitating further debridement, and remains on lifelong prophylactic antibiotic therapy.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Inflammatory bowel disease, Sulfasalazine, Neutropenia, Clostridium septicum

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium septicum (C. septicum) gas gangrene is not uncommonly described in the literature, invariably in the immunosuppressed patient. Though historically described as a complication of war wounds, in the present time it is usually associated with postoperative infections[1]. Crohn’s disease is an inflammatory bowel disease with variable luminal and extra-luminal manifestations. Because of the autoimmune nature of the disease, treatment is immunomodulatory in nature and common side effects include marrow suppression. We describe the development of C. septicum gas gangrene in a patient with Crohn’s disease, who was neutropenic as a result of treatment with sulfasalazine.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year-old man presented to the emergency department with the complaint of a few hours of feeling unwell with vomiting, diarrhea and pain in the left anterolateral thigh. His background history included long-standing diarrhea secondary to Crohn’s colitis diagnosed by colonoscopy 2 mo previously. The colitis was predominantly cecal, and the patient had been commenced on sulfasalazine treatment. Sulfasalazine had however been stopped 2 wk prior to presentation due to lack of efficacy, and prednisone was substituted.

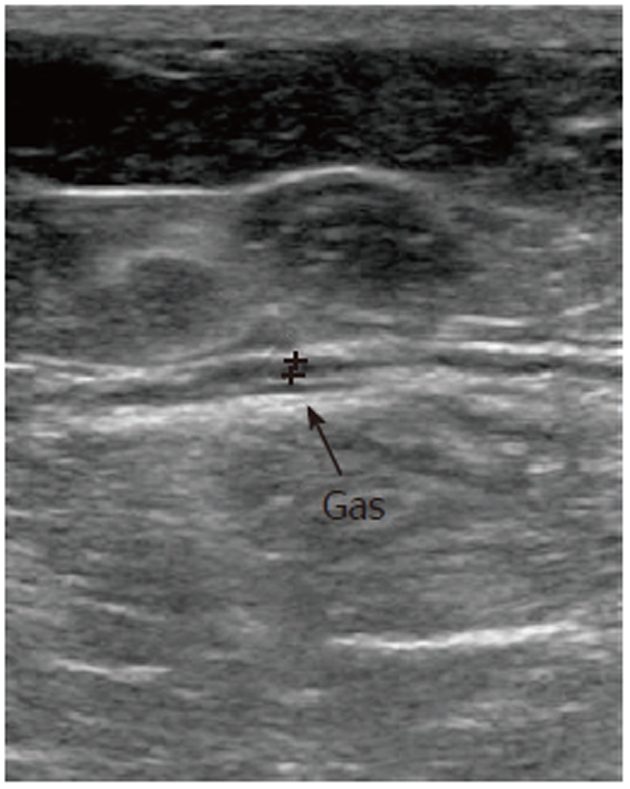

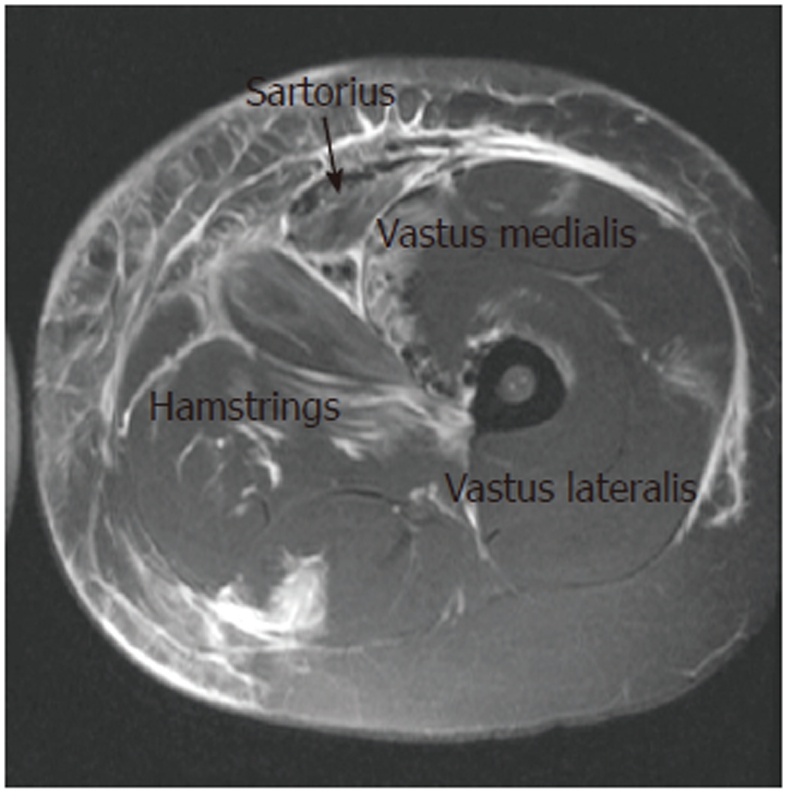

On initial examination the patient looked unwell and was tachycardic (150 bpm), though afebrile and normotensive. Respiratory and abdominal examinations were unremarkable, and the left anterolateral thigh was tender to palpation but otherwise normal in appearance. An initial ultrasound scan of the thigh also excluded any abnormality. Within 2 h the patient developed a fever to 38.5 °C and marked erythema of the left thigh with pustular formation. Initial laboratory investigations demonstrated a profound neutropenia (neutrophil count 0.2 × 109/L, white blood cell count 1.6 × 109/L) and myoglobinuria. An urgent repeat ultrasound scan of the anteromedial aspect of the left thigh demonstrated several small collections corresponding to pustule sites on the skin and visualized free gas near the obturator foramen (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed extensive necrotic myositis and extensive gas formation in the left vastus medialis down to the extensor tendon and neurovascular bundle and in the rectus femoris (Figure 2). A presumptive diagnosis of infective myonecrosis was made. The patient underwent emergency left hip disarticulation and exploratory laparotomy. Two days later an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed for investigation of induration of the abdominal wall, and demonstrated cecal edema with free gas in the cecal wall. Right hemicolectomy was then performed for colitis and gangrene. C. septicum was cultured from blood samples taken at initial presentation. Antibiotic treatment of intravenous lincomycin, meropenem and penicillin was given.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound scan of left anterior thigh demonstrating gas. Princess Alexandra Radiology Department, 2007.

Figure 2.

T2 fat suppressed magnetic resonance imaging of the left thigh, demonstrating changes of necrotizing myositis and gas formation. Princess Alexandra Hospital Radiology Department, 2007.

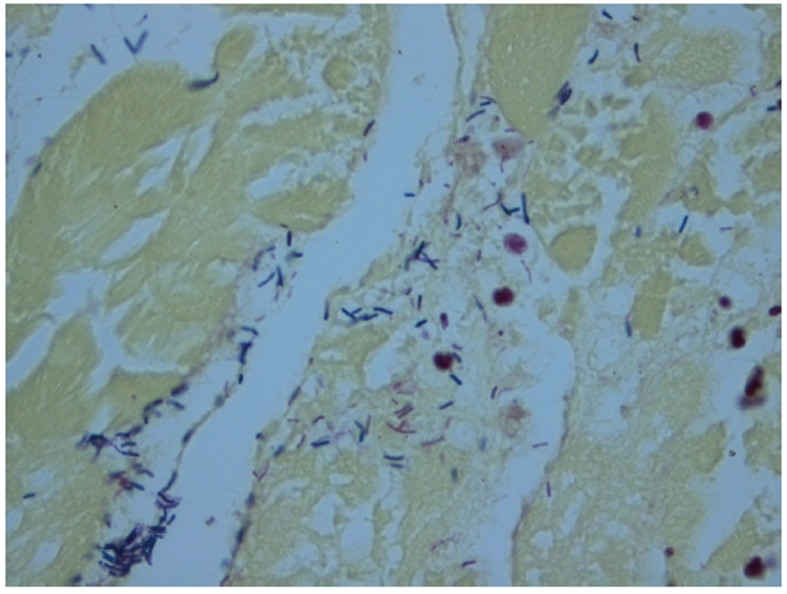

Routine hip stump washouts were performed and excluded progression of the necrotizing myositis. His recovery was complicated by a right pleural effusion requiring drainage. The patient was discharged from hospital on oral amoxicillin after a 3-wk stay. Two weeks after completion of the amoxycillin treatment the patient again presented with pain and erythema over the right pectoral muscle. A CT scan demonstrated an enlarged right pectoralis major muscle with inflammation of the overlying subcutaneous fat. The patient was taken to theatre where the necrotic pectoralis major muscle was debrided. C. septicum was cultured from the interoperative specimen (Figure 3). Antibiotic treatment during the perioperative period was intravenous benzylpenicillin, and the patient was also treated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy postoperatively. He had an uneventful recovery, and now remains on lifelong oral ampicillin prophylaxis.

Figure 3.

Necrotic chest wall muscle, with Clostridium septicum species. Pathology Queensland, Queensland Health-Princess Alexandra Hospital, 2007.

DISCUSSION

C. septicum is a large, spore-forming, gram-positive anerobic bacillus[2-4] found in the gastrointestinal tract of approximately 2% of the healthy population[5]. C. septicum is typically found in the cecum and ileocecal area, where factors including poor vascular supply, local redox potential, pH and the osmotic and electrolyte environment provide an environment conducive to proliferation[5-7]. The rapid proliferation and systemic toxicity that C. septicum causes is thought to be attributed to the production of four exotoxins[4]. The alpha toxin causes intravascular hemolysis, necrosis of host tissue, and increases capillary permeability, thus producing tachycardia and hypotension[2]. A hallmark of clostridial myonecrosis is a paucity of inflammatory cells in the affected tissue[2,5,8]. The necrotic process spreads rapidly to adjacent healthy tissue, causing massive necrotizing gangrene within hours[2].

C. septicum gas gangrene can be traumatic or non-traumatic. Traumatic gas gangrene historically complicated war wounds, and is now usually associated with postoperative infections[1]. Non-traumatic clostridial infections nearly always occur in the immunosuppressed patient, commonly in the setting of hematological or gastrointestinal cancer[5,7]. Diagnosis in a patient with spontaneous myonecrosis is often difficult as systemic symptoms are vague, and early localized findings can be mistaken for cellulitis. However, in a novel presentation, the triad of pain, tachycardia out of proportion to fever and crepitus is highly suggestive of clostridial myonecrosis[2,5].

We propose that in our patient, the ulcerated cecum allowed entry of C. septicum into the abdominal cavity, and this in concert with neutropenia secondary to sulfa-salazine provided an environment predisposing to rapid proliferation of the bacilli.

Sulfasalazine is a medication commonly used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, and a not uncommon complication is neutropenia. Mortality is high in Clostridium sepsis in the neutropenic milieu, and death usually occurs within 24 to 48 h[4,8]. For this reason, early diagnosis followed by immediate, aggressive surgical debridement is critical to survival[2,9]. It is therefore advisable that blood counts be monitored in patients who are commenced on this treatment, and that neutropenic patients receive emergency management should symptoms of sepsis arise.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Wolfgang R Stremmel, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Heidelberg, Medi-zinische Universitafsklinik, Heidelberg 49120, Germany

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Smith-Slatas CL, Bourque M, Salazar JC. Clostridium septicum infections in children: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e796–e805. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapnick EK, Abter EI. Infectious disease emergencies. Infect Dis Clin Am. 1996;10:835–855. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thalhammer F, Hollenstein U, Janata K, Knapp S, Koller R, Locker GJ, Staudinger T, Sunder-Plassmann G, Frass M, Burgmann H. A coincidence of disastrous accidents: Crohn’s disease, agranulocytosis, and Clostridium septicum infection. J Trauma. 1997;43:556–557. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199709000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foga MM, McGinn GJ, Kroeker MA, Guzman R. Sepsis due to Clostridium septicum: case report. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2000;51:85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corey EC. Nontraumatic gas gangrene: case report and review of emergency therapeutics. J Emerg Med. 1991;9:431–436. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(91)90214-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rich RS, Salluzzo RF. Spontaneous clostridial myonecrosis with abdominal involvement in a nonimmunocompromised patient. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1477–1480. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentine EG. Nontraumatic Gas Gangrene. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:109–111. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dylewski J, Drummond R, Rowen J. A case of Clostridium septicum spontaneous gas gangrene. CJEM. 2007;9:133–135. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500014950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abella BS, Kuchinic P, Hiraoka T, Howes DS. Atraumatic Clostridial myonecrosis: case report and literature review. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:401–405. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(03)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]