Abstract

Chronic pain is characterized by post-injury pain hypersensitivity. Current evidence suggests that it might result from altered neuronal excitability and/or synaptic functions in pain-related pathways and brain areas, an effect known as central sensitization. Increased activity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) has been well-demonstrated in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord in chronic pain animal models. Recently, increased ERK activity has also been identified in two supraspinal areas, the central amygdala and the paraventricular thalamic nucleus anterior. Our recent work on the capsular central amygdala has shown that this increased ERK activity can enhance synaptic transmission, which might account for central sensitization and behavior hypersensitivity in animals receiving noxious stimuli.

Key words: amygdala, central sensitization, chronic pain, LTP, parabrachial nucleus, paraventricular thalamic nucleus anterior, T-channel

Physiological pain serves as an early-warning protective system attributive to individuals to avoid noxious stimuli or harmful contact, or creates a circumstance to disfavor movement and physical contact to assist injured bodies to repair. On the other hand, non-protective-related pathological pain results from abnormality and dysfunction of the nervous system and consequently creates clinical pain syndromes with the greatest unmet need.1 Chronic pain is among the most disabling and costly afflictions. The American Chronic Pain Association estimates that one in three Americans (∼50 million) suffers from some type of chronic pain.2 Chronic pain is often accompanied by altered synaptic functions (usually hyperexcitability) of nociceptive pathways in the central nervous system, an effect known as central sensitization,3 in which the sensory system is rendered into a dysfunctional hyperalgesia state in which distinction of low-intensity stimuli and noxious stimuli is lost.

Central sensitization occurs not only in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, but also in the thalamus, amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in inflammatory, neuropathic and chemically-induced chronic pain.4 Being a part of the limbic system, the amygdala plays a key role in emotionality, including the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli, such as pain and emotional learning and memory5–8 and has been the subject of intensive investigation. The capsular central amygdala (CeAC) consists of many nociceptive neurons and is defined as the “nociceptive amygdala;”8–10 it receives large numbers of nociceptive-related fibers from the parabrachial nucleus (PB), a potine structure that relays nociceptive information from spinothalamic tracts to various forebrain areas, via the parabrachio-amygdaloid (PBA) pathway.10,11 In neuropathic and arthritic pain models, synaptic transmission of the PBA pathway on CeAC neurons (PBA-CeAC synapses) is enhanced.8,12,13 Nevertheless, the underlying cellular mechanism remains unclear.

Synaptic Plasticity and Chronic Pain

Long-term potentiation (LTP),14 is a prolonged increase in response to the same stimulus after a tetanizing stimulation train. LTP can be induced at the synapses of nociceptive inputs on dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord15 and in the ACC,16,17 in which most neurons respond to both noxious and non-noxious stimuli, after peripheral injury. The occurrence of LTP in these nociceptive-related pathways and areas is considered to be a part of the cellular mechanism underlying the development of central sensitization in chronic pain.18 At some cortical synapses, induction of LTP requires activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPKs) downstream of the activation of the N-methyl-D aspartate glutamatergic receptor (NMDAR).19–22 Interestingly, a biochemical hallmark of chronic pain is an increased level of phosphorylated (p)ERK and/or other MAPKs in the dorsal horn23–26 and the CeAC27 in formalin-induced pain and other chronic models. Direct injection of an ERK blocker or activator into the CeAC respectively increased or reduced nociceptive behavior in normal animals or those with formalin-induced or acid-induced pain, showing that activation of ERK in the CeAC directly causes central sensitization.27–29 Accordingly, it has been proposed that LTP and central sensitization may share common cellular mechanisms.18 In a recent study of PBA-CeAC synaptic transmission in normal mice and mice with acid-induced muscle pain (AIMP), we provided evidence that directly supports this argument.29

Synaptic Plasticity in AIMP

The AIMP model,30 first described and developed by Sluka et al. (2001), is generally accepted as an animal model for chronic musculoskeletal pain syndrome, such as fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndromes. In this model, animals receive a single injection of acidic saline into one side of the gastrocnemius muscle and develop transient mechanical hyperpalgesia in both hind paws. The hyperalgesia declines in 24 h but can become long-lasting for weeks if a second dose of acidic saline is given in 5 days. AIMP involves the activation of acid-sensing ion channel 3 in muscle nociceptors and requires central sensitization.31

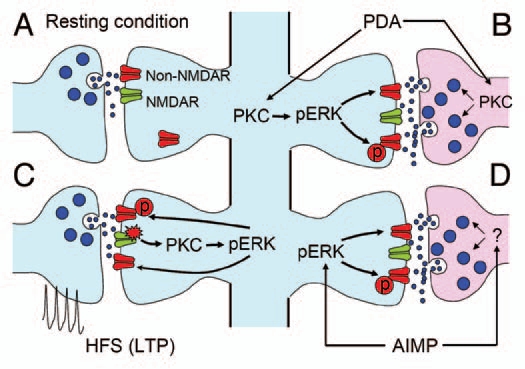

Consistent with studies of other models, we found an increased pERK level in both sides of the central amygdala in an AIMP model.28,29 To investigate whether such elevated pERK in CeAC is related to a change in the efficacy of PBA-CeAC synapses and behavioral hypersensitivity in AIMP, we examined the effect of an ERK activator, phorbol 12,13-diacetate (PDA), on the function of PBA-CeAC synapses. In addition to the well-known facilitating effect on glutamate release at many cortical synapses (Fig. 1A and B) through PKC-dependent upregulation of voltage-gated calcium channels located at axonal terminals32–34 and/or modulation of proteins involved in exocytosis,35,36 we found that the application of PDA also caused ERK-dependent postsynaptic enhancement of PBA-CeAC synaptic transmission, which might occur through the upregulation of non-NMDAR functions at synaptic sites.37,38 We also reported NMDAR-PKC-ERK-dependent LTP of PBA-CeAC synaptic transmission after the application of tetanizing stimulation (Fig. 1C). As PDA application to slices directly induces LTP and the induction of further LTP by tetanizing stimulation is occluded when slices are bathed in PDA, the postsynaptic enhancement by PDA and LTP by tetanizing stimulation might share common cellular mechanisms. Interestingly, PKC-ERK-dependent postsynaptic potentiation was not only observed when ERK was activated by bath-applied PDA, but also in animals with AIMP. Moreover, the postsynaptic enhancement by PDA and LTP by tetanizing stimulation seen in slices from normal mice was occluded in slices from AIMP mice. Based on these results, we propose that, in AIMP mice, an excessive nociceptive signal triggered by acidic saline injection into the gastrocnemius muscle activates ERK in the CeA, thereby enhancing PBA-CeAC synaptic transmission (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram summarizing PBA-CeAC synaptic transmission in normal and AIMP mice. (A) Synaptic transmission in a resting condition at PBA-CeAC synapses is mediated by non-NMDARs. (B) Application of PDA activates PKC in presynaptic terminals and postsynaptic dendrites. Activated PKC in presynaptic terminals enhances glutamate release, while that activated in postsynaptic spines activates ERK to upregulate non-NMDAR functions or increase their numbers at synaptic sites. (C) High-frequency stimulation activates NMDARs, which in turn activate the PKC-ERK signal pathway to upregulate non-NMDAR functions or increase their numbers at synaptic sites, thereby resulting in LTP. (D) In mice with AIMP, ERK is activated in the CeAC by an excessive nociceptive signal, which in turn upregulates non-NMDAR functions or increases their numbers at synaptic sites. In addition, enhanced glutamate release from presynaptic terminals was also observed in AIMP mice. Together, these pre- and postsynaptic enhancements at PBA-CeAC synapses might partially account for the central sensitization in AIMP.

T-channel and PVA

Although the observation of increased pERK levels in the central amygdala in AIMP mice is consistent with previous studies using other models, we found substantial differences between AIMP and other chronic pain models. First, mechanical hypersensitivity has been shown to be functionally lateralized to the right amygdala in intraplantar formalin and arthritic models;39–41 however, this phenomenon was not found in the AIMP model, as we constantly observed increased pERK in both sides of the central amygdala after acid injection.28,29 Second, in addition to the central amygdala, a profound increase in the number of neurons showing pERK immunoreactivity was found in the paraventricular thalamic nucleus anterior (PVA) in AIMP mice.28 The PVA belongs to the midline thalamic nuclei and is believed to serve as an important relay in the transfer of visceral/arousal and circadian information to parts of the limbic system, thereby priming them to a state of readiness for behavior responding.42,43 Recently, accumulating evidence has emerged to support a role of PVA in the modulation of nociception. PVA neurons receive nociceptive information indirectly from the PB44,45 and from regions that are important in generating pain perception, such as the ACC and central amygdale;46–50 they have been shown to respond to innocuous somatic and/or noxious stimuli51,52 with a widely receptive field. Pharmacological inactivation of ERK in PVA blocks acid-induced chronic hyperalgesia in mice.28

Interestingly, of brain areas (such as the CeA) showing an increased level of pERK in pain models, the PVA is the only area that involves T-type voltage-dependent calcium channel (T-channel) activity. Chronic hyperalgesia induced by acid injection was attenuated in Cav3.2-/- mice, and pharmacological blocking of T-channels inhibits the development of behavior hypersensitivity and elevation of the pERK level in the PVA in AIMP mice.28 The T-channels are involved in the regulation of many thalamic neuron functions, including the switching of the firing modes between continuous or burst.53,54 Recently, we have shown that T-channels might also contribute to the regulation of synaptic transmission of corticothalamic (CT) inputs on neurons in the ventrobasal nucleus, as synaptic efficacy of CT inputs could undergo a firing-mode-dependent plastic change.55 In addition, a growing amount of evidence has suggested a role of the T-channel in pain.15,56–61 Taking these lines of evidences together, it is obvious that further exploration of T-channel function in synaptic plasticity and neuronal excitability in the PVA, a newly-identified pain-related area, should provide new insight into the cellular mechanisms underlying the development of central sensitization at the supraspinal level.

In conclusion, plastic changes in synaptic transmission between pain-related brain areas have been shown to contribute to central sensitization and behavior hypersensitivity and ERK activation appears to play an important role in linking noxious stimuli to such functional changes. Mechanisms by which ERK are activated by noxious signals may vary among different pain-related brain areas. While NMDAR29 and/or group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor41 activation are involved in the central amygdala, PVA thalamic neurons involve T-channels.28

Abbreviations

- ACC

anterior cingulate cortex

- AIMP

acid-induced muscle pain

- CeAC

capsular central amygdala

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- PBA

parabrachio-amygdaloid

- PVA

paraventricular thalamic nucleus anterior

References

- 1.Woolf CJ. What is this thing called pain? J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3742–3744. doi: 10.1172/JCI45178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold MS, Gebhart GF. Nociceptor sensitization in pain pathogenesis. Nat Med. 2010;16:1248–1257. doi: 10.1038/nm.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf CJ. Evidence for a central component of post-injury pain hypersensitivity. Nature. 1983;306:686–688. doi: 10.1038/306686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain. 2009;10:895–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis M. Anatomic and physiologic substrates of emotion in an animal model. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;15:378–387. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zald DH. The human amygdala and the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Brain Res Rev. 2003;41:88–123. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neugebauer V, Li W, Bird GC, Han JS. The amygdala and persistent pain. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:221–234. doi: 10.1177/1073858403261077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard JF, Huang GF, Besson JM. Nucleus centralis of the amygdala and the globus pallidus ventralis: electrophysiological evidence for an involvement in pain processes. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:551–569. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.2.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernard JF, Bester H, Besson JM. Involvement of the spino-parabrachio -amygdaloid and -hypothalamic pathways in the autonomic and affective emotional aspects of pain. Prog Brain Res. 1996;107:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gauriau C, Bernard JF. Pain pathways and parabrachial circuits in the rat. Exp Physiol. 2002;87:251–258. doi: 10.1113/eph8702357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neugebauer V, Li W, Bird GC, Bhave G, Gereau RW. Synaptic plasticity in the amygdala in a model of arthritic pain: differential roles of metabotropic glutamate receptors 1 and 5. J Neurosci. 2003;23:52–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00052.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda R, Takahashi Y, Inoue K, Kato F. NMDA receptor-independent synaptic plasticity in the central amygdala in the rat model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda H, Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Synaptic plasticity in spinal lamina I projection neurons that mediate hyperalgesia. Science. 2003;299:1237–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1080659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei F, Zhuo M. Potentiation of sensory responses in the anterior cingulate cortex following digit amputation in the anaesthetised rat. J Physiol. 2001;532:823–833. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0823e.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhuo M. A synaptic model for pain: long-term potentiation in the anterior cingulate cortex. Mol Cells. 2007;23:259–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization and LTP: do pain and memory share similar mechanisms? Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin YW, Min MY, Chiu TH, Yang HW. Enhancement of associative long-term potentiation by activation of beta-adrenergic receptors at CA1 synapses in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4173–4181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04173.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin YW, Yang HW, Wang HJ, Gong CL, Chiu TH, Min MY. Spike-timing-dependent plasticity at resting and conditioned lateral perforant path synapses on granule cells in the dentate gyrus: different roles of N-methyl-D-aspartate and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2362–2374. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannini MG, Blitzer RD, Wong T, Asoma K, Tsokas P, Morrison JH, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates early phosphorylation and delayed expression of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7053–7062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07053.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Impey S, Obrietan K, Storm DR. Making new connections: role of ERK/MAP kinase signaling in neuronal plasticity. Neuron. 1999;23:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garry EM, Delaney A, Blackburn-Munro G, Dickinson T, Moss A, Nakalembe I, et al. Activation of p38 and p42/44 MAP kinase in neuropathic pain: involvement of VPAC2 and NK2 receptors and mediation by spinal glia. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;30:523–537. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji RR, Baba H, Brenner GJ, Woolf CJ. Nociceptive-specific activation of ERK in spinal neurons contributes to pain hypersensitivity. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1114–1119. doi: 10.1038/16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ji RR, Gereau RWt, Malcangio M, Strichartz GR. MAP kinase and pain. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei F, Vadakkan KI, Toyoda H, Wu LJ, Zhao MG, Xu H, et al. Calcium calmodulin-stimulated adenylyl cyclases contribute to activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in spinal dorsal horn neurons in adult rats and mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:851–861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3292-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrasquillo Y, Gereau RW. Activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the amygdala modulates pain perception. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1543–1551. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3536-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen WK, Liu IY, Chang YT, Chen YC, Chen CC, Yen CT, et al. Ca(v)3.2 T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent activation of ERK in paraventricular thalamus modulates acid-induced chronic muscle pain. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10360–10368. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1041-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng SJ, Chen CC, Yang HW, Chang YT, Bai SW, Chen CC, et al. Role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in synaptic transmission and plasticity of a nociceptive input on capsular central amygdaloid neurons in normal and acid-induced muscle pain mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2258–2270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5564-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sluka KA, Kalra A, Moore SA. Unilateral intramuscular injections of acidic saline produce a bilateral, long-lasting hyperalgesia. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:37–46. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200101)24:1<37::aid-mus4>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sluka KA, Price MP, Breese NM, Stucky CL, Wemmie JA, Welsh MJ. Chronic hyperalgesia induced by repeated acid injections in muscle is abolished by the loss of ASIC3, but not ASIC1. Pain. 2003;106:229–239. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parfitt KD, Madison DV. Phorbol esters enhance synaptic transmission by a presynaptic, calcium-dependent mechanism in rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1993;471:245–268. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stea A, Soong TW, Snutch TP. Determinants of PKC-dependent modulation of a family of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1995;15:929–940. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swartz KJ, Merritt A, Bean BP, Lovinger DM. Protein kinase C modulates glutamate receptor inhibition of Ca2+ channels and synaptic transmission. Nature. 1993;361:165–168. doi: 10.1038/361165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hori T, Takai Y, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism for phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7262–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lou X, Korogod N, Brose N, Schneggenburger R. Phorbol esters modulate spontaneous and Ca2+-evoked transmitter release via acting on both Munc13 and protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8257–8267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0550-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derkach VA, Oh MC, Guire ES, Soderling TR. Regulatory mechanisms of AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrn2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmid A, Hallermann S, Kittel RJ, Khorramshahi O, Frolich AM, Quentin C, et al. Activity-dependent site-specific changes of glutamate receptor composition in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:659–666. doi: 10.1038/nn.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrasquillo Y, Gereau RW. Hemispheric lateralization of a molecular signal for pain modulation in the amygdala. Mol Pain. 2009;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ji G, Neugebauer V. Hemispheric lateralization of pain processing by amygdala neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:2253–2264. doi: 10.1152/jn.00166.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolber BJ, Montana MC, Carrasquillo Y, Xu J, Heinemann SF, Muglia LJ, et al. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in the amygdala modulates pain-like behavior. J Neurosci. 2010;30:8203–8213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1216-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moga MM, Weis RP, Moore RY. Efferent projections of the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:221–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vertes RP, Hoover WB. Projections of the paraventricular and paratenial nuclei of the dorsal midline thalamus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:212–237. doi: 10.1002/cne.21679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bester H, Bourgeais L, Villanueva L, Besson JM, Bernard JF. Differential projections to the intralaminar and gustatory thalamus from the parabrachial area: a PHA-L study in the rat. J Com Neurol. 1999;405:421–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krout KE, Loewy AD. Parabrachial nucleus projections to the midline and intralaminar thalamic nucleus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:475–494. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001218)428:3<475::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen S, Su HS. Afferent connections of the thalamic paraventricular and parataenial nuclei in the rat—a retrograde tracing study with iontophoretic application of Fluoro-Gold. Brain Res. 1990;522:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91570-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krout KE, Belzer RE, Loewy AD. Brainstem projections to midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2002;448:53–101. doi: 10.1002/cne.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novak CM, Harris JA, Smale L, Nunez AA. Suprachiasmatic nucleus projections to the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in nocturnal rats (Rattus norvegicus) and diurnal nile grass rats (Arviacanthis niloticus) Brain Res. 2000;874:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otake K, Ruggiero DA, Nakamura Y. Adrenergic innervation of forebrain neurons that project to the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the rat. Brain Res. 1995;697:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00749-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peschanski M, Besson JM. Diencephalic connections of the raphe nuclei of the rat brainstem: an anatomical study with reference to the somatosensory system. J Comp Neurol. 1984;224:509–534. doi: 10.1002/cne.902240404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dostrovsky JO, Guilbaud G. Nociceptive response in medial thalamus of the normal and the arthritic rat. Pain. 1990;40:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91056-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reyes-Vazquez C, Prieto-Gomez B, Dafny N. Noxious and non-noxious responses in the medial thalamus of the rat. Neurol Res. 1989;11:177–180. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1989.11739887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bal T, McCormick DA. Mechanisms of oscillatory activity in guinea-pig nucleus reticularis thalami in vitro: a mammalian pacemaker. J Physiol. 1993;468:669–691. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherman SM. Tonic and burst firing: dual modes of thalamocortical relay. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:122–126. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hsu CL, Yang HW, Yen CT, Min MY. Comparison of synaptic transmission and plasticity between sensory and cortical synapses on relay neurons in the ventrobasal nucleus of the rat thalamus. J Physiol. 2010;588:4347–4363. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altier C, Zamponi GW. Targeting Ca2+ channels to treat pain: T-type versus N-type. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;5:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng JK, Lin CS, Chen CC, Yang JR, Chiou LC. Effects of intrathecal injection of T-type calcium channel blockers in the rat formalin test. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:1–8. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280141375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi S, Na HS, Kim J, Lee J, Lee S, Kim D, et al. Attenuated pain responses in mice lacking Ca(V)3.2 T-type channels. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:425–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jagodic MM, Pathirathna S, Nelson MT, Mancuso S, Joksovic PM, Rosenberg ER, et al. Cell-specific alterations of T-type calcium current in painful diabetic neuropathy enhance excitability of sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3305–3316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4866-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Meyenburg A, Mennerick S, Perez-Reyes E, Romano C, et al. Redox modulation of T-type calcium channels in rat peripheral nociceptors. Neuron. 2001;31:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Todorovic SM, Meyenburg A, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Mechanical and thermal antinociception in rats following systemic administration of mibefradil, a T-type calcium channel blocker. Brain Res. 2002;951:336–340. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]