Abstract

The rationale for identifying markers of latent schizophrenia is the evidence that early treatment speeds remission and lessens long-term deterioration. Unfortunately hovever, although the childhood and adolescence of individual psychotics often reveal premorbid deviations from established norms, while epidemiological studies identify cognitive performance and social adjustment as potential premorbid markers, such signs vary widely and no typical prodrome has been identified. Illness-related events or behaviors are not the only factors precipitating the transition from premorbid to prodrome: educational and socioeconomic status are also involved, it follows that there is a controversy surrounding the secondary prevention of schizophrenia: because of the poor specificity of premorbid and prodromal markers, treating such patients implies thai an unacceptably high proportion of individuals who will not ultimately develop florid schizophrenia will be exposed to stigma of a provisional diagnosis of severe mental illness as well as to the adverse effects of treatment Schizophrenia, therefore, is an aggravated illustration of the dilemmas facing much preventive therapy.

Keywords: detection, early treatment, secondary prevention, premorbid markers, prodromal period, schizophrenia

Abstract

El motivo principal para la identificación de marcadores de la esquizofrenia latente se basa en que el tratamiento precoz acelera la remisión y reduce ei deterioro a largo plazo. Lamentablemente, aunque por una parte la niñezy la adolescencia de los individuos psicóticos revelan a menudo desviaciones premôrbidas de las normas establecidas y por otra, los estudios epidemiológicos identifican el rendimiento cognitivo y la adaptación social como potenciales marcadores premórbidos, taies signos varian ampliamente y no se ha identificado ningún pródromo como típico. Los acontecimientos o las conductas relacionadas con la enfermedad no son los únicos factores précipitantes para la iransición desde la condición premôrbida al pródromo; también esián involucrados el nivel educacional y el nivel socioeconómico. A causa del carácter inespecifico de los marcadores premórbidos y prodrómicos, una intervención preventiva y sistemática implica tratar una proporción elevada y inaceptable de individuos que finalmente no desarollarán una esquizofrenia. Esios individuos corren el riesgo del perjuicio de un diagnóstico psiquiátrico provisionalmente severo y de los efectos secundarios del tratamiento. La esquizofrenia es una ilusiración de peso de los dilemas que enfrenta la terapia preventiva.

Abstract

La recherche de marqueurs de la schizophrénie latente se justifie par le fait que le traitement précoce de cette affection accélère sa rémission tout en réduisant la détérioration à long terme. Malheureusement, alors que l'enfance ei l'adolescence des individus psychotiques révèlent souvent des déviations prémorbides par rapport aux normes établies et que les études épidémiologiques identifient la performance cognitive et l'adaptation sociale comme des marqueurs prémorbides possibles, de tels signes varient largement sans qu'aucun prodrome typique n'ait pu être défini. Les événements ou les comportements liés à la maladie ne sont pas les seuls facteurs susceptibles de précipiter le passage du stade prémorbide à celui de prodrome: les niveaux éducatif et socio-économique sont également impliqués. D'où la controverse autour du traitement précoce de la schizophrénie: en raison de la médiocre spécificité des marqueurs prémorbides et prodromiques, une approche préventive systématique implique que l'on traiterait une proportion élevée ei inacceptable de sujets qui ne développeront pas de schizophrénie déclarée et seront exposés au préjudice lié à la formulation d'un diagnostic provisoire de maladie psychiatrique sévère ainsi qu'aux effets secondaires du traitement, La schizophrénie représente ainsi une illustration particulièrement sévère des dilemmes rencontrés dans le cadre de nombreux traitements préventifs.

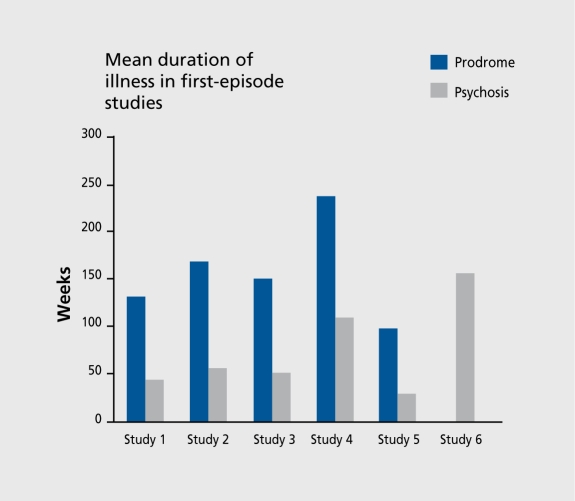

History taken upon the first contact between a psychotic adolescent or young adult and a mental health professional often reveals subtle deviations from established norms that were present before the psychosis. The realms of the deviations are motor, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral during childhood; social withdrawal and mood and personality changes during adolescence; and attenuated psychotic symptoms several months to several years before the first treatment contact and the diagnosis of psychosis(Figure 1).1-6The period immediately preceding the onset of psychosis, during which behavior and functioning deteriorates from a stable, “premorbid” level of functioning and behavioral changes occur is referred to as the “prodromal” period. However, the factors that precipitate the transition from premorbid to prodrome or the first incidence of seeking help and the resultant diagnosis are not necessarily distinct illness-related events or behaviors.

Figure 1. The lag-time between the first manifestation of schizophrenia in the community and the first treatment contact. Study 1: McGorry et al,11998, Australia; Study 2: Beiser et ai,21993, Canada; Study 3: Loebel et al,31992, USA; Study 4: Hafner et al,41997, Germany; Study 5: Perkins et al,52000, USA; Study 6: Haas and Sweeney,61992, USA.

Factors such as the educational level of patients and their families, socioeconomic status, and availability of health care may all determine when the first contact occurs.7,8Also, events such as the sudden unavailability of a caregiver able to maintain a highly symptomatic individual in the community or any change in the threshold of abnormal behavior tolerated by the community can precipitate treatment contact, hospitalization, and diagnosis. Hence, the presence of the premorbid manifestation, the onset of the prodrome, the emergence of the symptoms that define an episode of the illness, and ascertainment of the full syndrome of illness including formal diagnosis do not necessarily coincide and are not always clearly distinct points in time.

Methods employed to investigate the phenomena preceding the first contact for help and the diagnosis of schizophrenia are thehigh-risk method,thebirth cohort method,andhistorical prospective (or follow back) method.

High-risk studiesthat followed offspring and siblings of individuals affected by schizophrenia into adulthood have demonstrated that these relatives arc more likely than the general population to be affected by emotional and behavioral abnormalities and abnormal psychophysiological reactions. However, despite the fact that increased risk can be demonstrated in these populations, this strategy has not been helpful in the study of the premorbid phase of schizophrenia, because most of the individuals who belong to the high-risk groups represent a small, atypical subgroup of patients with schizophrenia.

Follow-up studiesof individuals born in a geographically defined area over a specified period of time (birth cohort) have mostly been carried out by national health authorities to study protective and risk factors for healthy development and disease. Among the most publicized and complete studies are two British studies: the .Medical Research Council National Survey of Development, covering all births during the week 3 to 9 March 1946,9and the National Child Development Study, covering all births during the week 3 to 9 March 1958.10Developmental and scholastic achievement data collected for these cohorts were later linked to the data in a registry containing diagnoses of individuals discharged from psychiatric hospitals. An overview of these studies indicates that, as a group, future schizophrenia cases had delayed developmental milestones, speech and behavioral difficulties, and 1Q scores lower by two thirds of a standard deviation compared with individuals who do not appear in the psychiatric registry. Although future cases were overrepresented in the lowest third of the IQ scores, the level of performance seen was not necessarily even outside the average range of 10 scores (defined as 10s between 90 and 110, which is 0.67 SD above or below the average score of 100).

Follow-back or historical prospective studiesexamine the premorbid histories of individuals who have already been diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia. These can be based on the linkage of databases containing routine psychometric tests administered by educational or military authorities to large numbers of healthy adolescents, with national psychiatric registries.

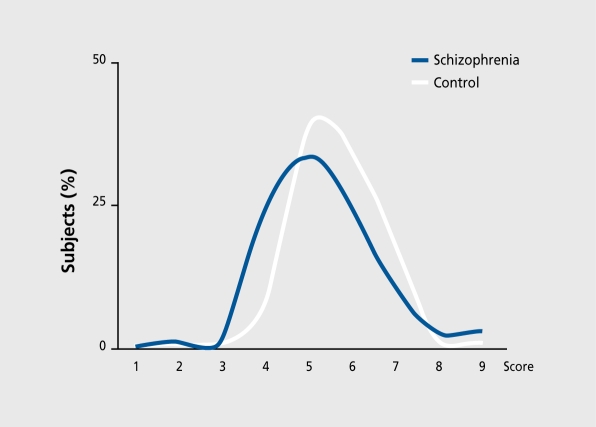

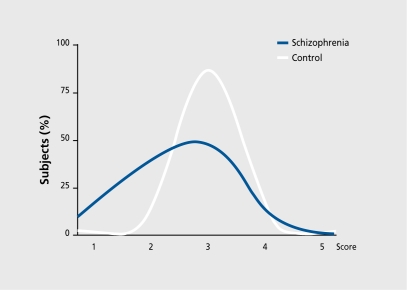

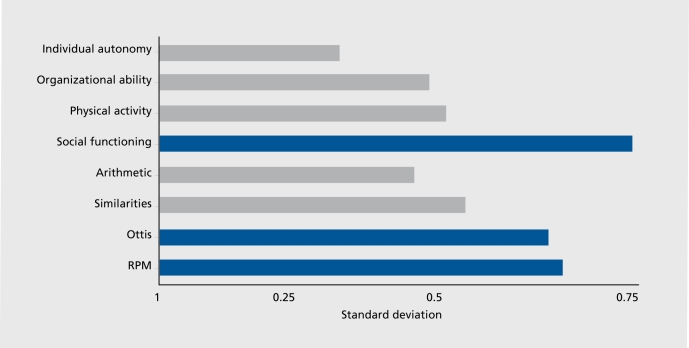

A study based on a national population of adolescents called by the Israeli Draft Board Registry11revealed that apparently healthy individuals who several years later developed schizophrenia had lower mean group scores than their healthy classmates by about 1 SD on items reflecting social adjustment and IQ (Figure 2 and Figure 3).The differences derive from a “shift to the left” of the future patients - one that was clearly more pronounced on social adjustment than on IQ (Figure 3).Despite the consistency between these results, their interpretation remains uncertain. The premorbid signs of the illness are widely variable and a single “typical prodrome” cannot be identified. Some individuals manifest shyness detectable in elementary school, many years before the manifestation of psychosis; others have 10 scores 0.5 to 0.8 SD lower than expected(Figure 4);and yet others manifest progressive, continuous deterioration during childhood and adolescence. It is possible that some of the variability in the quality and time of premorbid manifestations reflect limitations of the study design, which are often cross-sectional assessments. A true prospective follow-up study, specifically designed to detect signs of premorbid schizophrenia from birth through to the age of risk, may reveal that an individual who manifests mild delay in developmental milestones as a toddler, learning difficulties in elementary school, poor peer inter-action as a teenager, and depressed mood as an adolescent will develop psychosis as a young adult. Alternatively, a particular premorbid manifestation might lead to a particular subtype of schizophrenia.

Figure 2. Distribution of IQ in patients with schizophrenia and normal controls.

Figure 3. Distribution of social functioning score in patients with schizophrenia and normal controls.

Figure 4. Effect size of differences in future schizophrenia patients. RPM: Raven progressive matrices; Ottis: a test of attention.

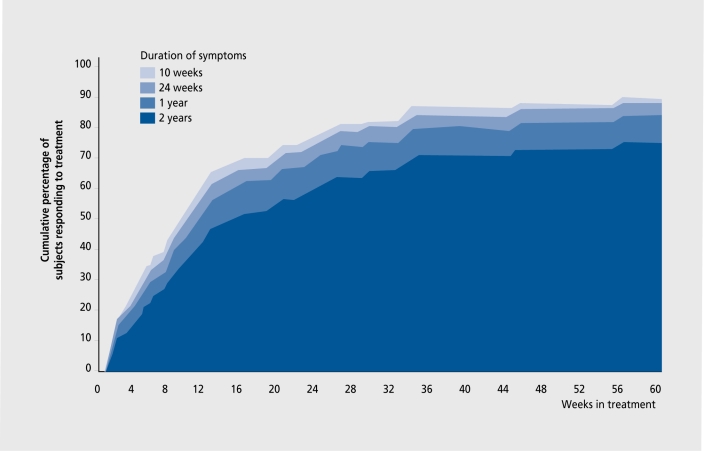

From a practical point of view, it would be tempting to utilize the occurrence of the premorbid and prodromal manifestations of the illness to identify individuals at imminent risk of developing schizophrenia and intervene before the onset of the first psychotic episode, in an attempt to delay or ameliorate it. It would be reasonable to hypothesize that any intervention that would delay or attenuate the first psychotic episode would have a major impact on the long-term outcome of the illness. This idea draws support from studies indicating that patients with shorter duration of untreated psychosis have more rapid symptomatic remission and may incur less deterioration in the long run(Figure 5).12

Figure 5. Time to remission according to prior duration of psychosis (Lieberman JA, personal communication).

Table I. Potential early markers and risks. CPT: continued performance test.

| • Family history |

| • Perinatal complications |

| • Subtle developmental delay |

| • Subtle deviation on psychometric performance |

| • Mild behavioral abnormalities |

| • Stress, immigration, use of drugs? |

| • Depressed mood and social decline |

| • Attenuated or transient psychosis |

| • Electrophysiological and attention (CPT) markers? |

| • Late paternal age at gestation |

However, the relatively low specificity of the premorbid and prodromal markers(Table I)has given rise to concerns that an excessive number of individuals might be unnecessarily exposed to the stigma of a provisional diagnosis of severe mental illness.

Therefore, the question of treating individuals who are not yet floridly psychotic has stirred public and professional debate. Yet, because of the potential benefits of secondary prevention on one hand and the risks and ethical implications associated with it on the other, it is essential to search for rational strategies to assess the risk-benefit ratio. Examining such ratios in an area where preventive measurements are already an accepted reality would be such a strategy. For example, despite the fact that following remission from the first psychotic episode only 60% of the drug-free patients will exacerbate within the first year, 100% of the patients are routinely treated with neuroleptics. Hence, 40% of patients will be exposed to the adverse effects of neuroleptics, but are unlikely to experience a worsening of their symptoms. Similarly, seven families of schizophrenic patients must go through the effort, expense, and potential adverse effects of intensive family therapy for 1 year, to prevent relapse on the part of one out of seven recently discharged schizophrenic patients.

The dilemma of preventive treatment is not limited to psychiatry. For instance, approximately 70 elderly patients with moderate hypertension must be treated with antihypertensive drugs for 5 years to save one life, and 100 men with no evidence of coronary heart disease must be treated with aspirin for 5 years to prevent one heart attack.

The early detection and treatment strategy is supported by preliminary results from a community clinic where youths with prodromal symptoms were treated with open-label neuroleptics plus supportive measures, or supportive measures alone. The results indicate that more members of the neuroleptic-treated group were symptom-free for a longer period of time than similar youths given only supportive therapy or those who refused to enroll in the trial. In a different study, nonpsychotic, first-degree relatives of patients complaining mostly of cognitive deficit also were found to benefit from neuroleptic treatment.

In summary, while there is much interest in the events leading to the first psychotic episode and a strong appeal for secondary prevention, the information currently available is still tentative(Table II).In contrast, there is much information and a few solid practical implications regarding the first episode of psychosis.

Table II. Early detection and treatment of schizophrenia.

| Is early détection and secondary prevention of schizophrenia a realistic goal? |

| • Can premorbid and prodromal manifestations of schizophrenia be utilized for early detection and intervention? |

| • Can early intervention delay the onset of the disease, ameliorate its manifestation, or improve the long-term outcome? |

| • Do the risks for false-positive identification and stigmatization justify the potential benefits? |

| Rational for early detection and treatment |

| • The lag-time between the first manifestation of schizophrenia and the first treatment contact ranges between a few month and a few years |

| • First-episode patients treated earlier rather than later had a faster remission |

| • Patients whose illness started after neuroleptics were available on a large scale (1970) have a better long-term outcome |

| • Because schizophrenia has its onset at a critical age for social and vocational development, any delay in onset or amelioration of symptoms carries a large impact in outcome |

| Minimal requirements for early treatment with antipsychotic drugs |

| • Predictive test |

| - Easy applicable, reliable, specific for the illness being treated |

| • Treatment |

| - Good risk-benefit ratio |

| - Minimal and reversible adverse effects |

| - Low cost |

REFERENCES

- 1.Yung AR., Phillips LJ., McGorry PD., et al. Prediction of psychosis. A step towards indicated prevention of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beiser M., Erickson D., Flaming JA., lacono WG. Establishing the onset of psychotic illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1349–1354. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.9.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loebel AD., Lieberman JA., Alvir JM., Mayerhoff Dl., Geisler SH., Szymanski SR. Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Am j Psychiatry. 1992;149:1183–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hafner H., an der Heiden W. Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:139–151. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkins DO., Leserman J., Jarskog LF., Graham K., Kazmer J., Lieberman JA. Characterizing and dating the onset of symptoms in psychotic illness: the Symptom Onset in Schizphrenia (SOS) inventory. Schizophr Res. 2000;44:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas GL., Sweeney JA. Premorbid and onset features of first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:373–386. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hambrecht M., Hafner H., Loffler W. Beginning schizophrenia observed by significant others. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1994;29:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00805621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinrichsen GA., Lieberman JA. Family attributions and coping in the prediction of emotional adjustment in family members of patients with firstepisode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100:359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones P., Rodgers B., Muray R., Marmot M. Child Development risk factors for adult schizophrenia in the British 1946 birth cohort. Lancet. 1994;344:1398–1402. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Done DJ., Crow TJ., Johnstone EC., Sacker A. Childhood antecedents of schizophrenia and affective illness: social adjustment at ages 7 and 11 . BMJ. 1994;309:699–703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6956.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson M., Reichenberg A., Rabinowitz J., Weiser M., Kaplan Z., Mark M. Behavioral and intellectual markers for schizophrenia in apparently healthy male adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1328–1335. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberman JA., Alvir JM., Koreen A., et al. Psychobiologic correlates of treatment response in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14(suppl):13S–21S. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00200-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]