Abstract

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is the second most common cause of neurodegenerative dementia in older people, accounting for 10% to 15% of all cases, it occupies part of a spectrum that includes Parkinson's disease and primary autonomic failure. All these diseases share a neuritic pathology based upon abnormal aggregation of the synaptic protein α-synuciein. It is important to identify DLB patients accurately because they have specific symptoms, impairments, and functional disabilities thai differ from other common dementia syndromes such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular cognitive impairment, and frontotemporal dementia. Clinical diagnostic criteria for DLB have been validated against autopsy, but fail to detect a substantial minority of cases with atypical presentations that are often due to the presence of mixed pathology. DLB patients frequently have severe neuroleptic sensitivity reactions, which are associated with significantly increased morbidity and mortality. Cholinesterase inhibitor treatment is usually well tolerated and substantially improves cognitive and neuropsychiatrie symptoms. Although virtually unrecognized 20 years ago, DLB could within this decade become one of the most treatable neurodegenerative disorders of late life.

Keywords: Lewy body, dementia, Parkinson's disease, α-synuclein, diagnosis, treatment, cholinesterase inhibitor

Abstract

La demencia con cuerpos de Lewy (DCL) es la segunda causa más común de demencia neurodegenerative en las personas de edad avanzada y representa el 10% a 15% de todos los casos. Ocupa parte de un espectro que incluye la enfermedad de Parkinson y la insuficiencia autonómica primaria. Todas estas enfermedades comparten una patología neural que se basa en una agregación anormal de la proteína sináptica α-sinucleina. Es importante identificar pacientes con DCL con precisión ya que ellos tienen síntomas específicos, deterioros y discapacidades funcionales que difieren de otros síndromes comunes de demencia como la enfermedad de Alzheimer, el deterioro cognitivo vascular y la demencia frontotemporal. Se han validado criterios diagnósticos clínicos para la DCL mediante la autopsia, pero fallan en la detección de una minoría no despreciable de casos con presentaciones atípicas que a menudo se deben a la presencia de patología mixta. Los pacientes con DCL tienen frecuentemente graves reacciones de sensibilidad a los neurolépticos, las que están asociadas con un aumento significativo de la morbilidad y de la mortalidad. El tratamiento con inhibidores de la colinesierasa en general es bien tolerado y mejora significativamente los síntomas cognitivos y neuropsiquiátricos. Aunque virtualmente la DCL no se reconocía hace 20 años, dentro de esta década podría llegar a ser uno de los trastornos neurodegenerativos más tratables de la vejez.

Abstract

La démence à corps de Lewy (DCL) représente la deuxième cause la plus fréquente des démences neurodegeneratives chez les sujets âgés, soit 10 à 15 % de l'ensemble des cas. Elle appartient à un éventail qui va de la maladie de Parkinson à la déficience autonome primaire. Toutes ces maladies partagent une pathologie neuronale basée sur une agrégation anormale de la protéine synaptique α-synucléine. Il est important d'identifier avec précision les patients atteints de DCL car leurs symptômes, déficits ou incapacités fonctionnelles sont spécifiques et diffèrent des autres syndromes démentiels courants comme la maladie d'Alzheimer, le déficit vasculaire cognitif et la démence frontotemporale. Les critères diagnostiques cliniques pour la DCL ont été validés par autopsie mais une minorité non négligeable n'est pas détectée, il s'agit de cas atypiques dont la pathologie est souvent mixte. Les patients atteints de DCL ont souvent une hypersensibilité sévère aux neuroleptiques, associée à une morbidité et une mortalité significativement accrues. Le traitement par anticholinestérasiques est habituellement bien toléré et améliore considérablement les symptômes cognitifs et neuropsychiatriques. Bien que pratiquement méconnue il y a 20 ans, la DCL pourrait devenir au cours des 10 ans à venir l'une des maladies neurodégénératives de survenue tardive les plus accessibles au traitement.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is probably the second most prevalent cause of degenerative dementia in older people; only Alzheimer's disease (AD) is more common. For example, a recent community study of 85+ year olds found 5.0% to meet clinical diagnostic criteria for DLB, representing 22% of all demented cases.1 Despite its high prevalence, DLB was only fully recognized about, a decade ago, as a result, of improved methods of neuropathological staining, which allowed the key lesions (Lewy bodies f LBs]) to be seen in autopsy brain tissue.2 It is therefore a relative newcomer for many clinicians, for whom it. poses significant, difficulty in antemortem diagnosis. The importance of recognizing DLB relates particularly to its pharmacological management, with reports of good responsiveness to cholinesterase inhibitors,3 but extreme sensitivity to the side effects of neuroleptics.4,5 This article, which reviews current knowledge and opinion about DLB, is based upon the deliberations of two recent, international consensus meetings.6,7

Diagnostic concepts

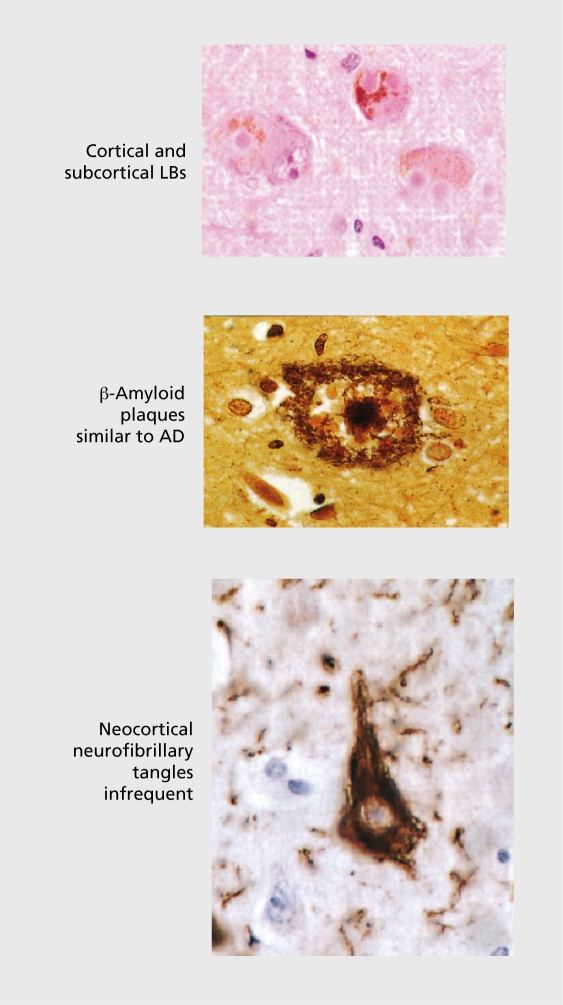

DLB has carried a variety of diagnostic labels during the last two decades, including diffuse Lew}' body disease (DLBD),8 Lewy body dementia (LBD),9 the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease (LBVAD),10 senile dementia of Lewy body type (SDLT),11 and dementia associated with cortical Lewy bodies (DCLB).12This multiplicity of terms reflects the coexistence in the brains of these cases of α-synuclcin–positive LBs and Lewy ncurites (LNs) and abundant Alzheimer-type pathology, predominantly in the form of amyloid plaques. Tau-positive inclusions and neocortical neurofibrillary tangles sufficient to meet. Braak stages V or VI occur in only a minority of cases (Figure 1). Alzheimer pathology is not. a prerequisite for the existence of dementia however, since cases with “pure” LB disease may present, clinically with cognitive impairment and other neuropsychiatrie features. Nor is the number of cortical LBs robustly correlated with either the severity or the duration of dementia,13,14 although associations have been reported with LB and plaque density in midfrontal cortex.15 LN and neurotransmitter deficits are suggested as more likely correlates of clinical symptoms.14,16

Figure 1. The neuropathology of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). LBs, Lewy bodies; AD, Alzheimer's disease.

α-Synuclein immunoreactive deposits with many of the characteristics of LBs have also been reported in a high proportion of AD cases, particularly in the amygdala.17 In this context, they may represent an end-stage phenomenon, with secondary accumulation of aggregated synuclein in severely dysfunctional neurones that are already heavily burdened by plaque and tangle pathology.18 Whatever the explanations arc for this considerable overlap in pathological lesions in DLB and AD, it is clear that clinical separation of cases is going to be less than 100% precise. The presence of Alzheimer pathology in DLB appears to modify the typical clinical presentation making such cases harder to differentiate clinically,19 with the core features (see below) being scant or absent and the clinical picture more closely resembling AD.

DLB and Parkinson's disease dementia

The clinical and pathological classification of DLB is further complicated by its relationship with idiopathic Parkinson's disease, a disorder in which dementia may develop in up to 78% patients20 and which is similar to DLB21,22 in respect of fluctuating neuropsychological function,23 neuropsychiatrie features,24 and extrapyramidal motor features (Table I):5

Table I. Similarities between dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD).

| Cognitive profile |

| Fluctuating cognition |

| Extra pyramidal features |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms |

| Lewy body distribution and density |

| Cholinergic and dopaminergic deficits |

| Neuroleptic sensitivity |

| Response to cholinesterase inhibitors |

There is considerable debate as to the relationship between the two diagnoses.26 An arbitrary “1-year rule” is frequently used to “separate” them by proposing that onset, of dementia within 12 months of parkinsonism qualifies as DLB and more than 12 months of parkinsonism before dementia qualifies as Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD).This is certainly helpful in individual clinical case diagnosis and management, but is increasingly hard to justify from a neurobiological point of view. There do not seem to be major neuropathological differences between DLB and PDD, and it is not. possible to make a confident retrospective clinical diagnosis based on autopsy findings alone. A Task Force of the Movement. Disorders Society is presently addressing the issues of PD dementia, and its recommendations should help to clarify this complex and currently problematic area.

Clinical criteria for DLB

The core clinical features of DLB, as defined by consensus criteria (Table II.);27 are fluctuating cognitive impairment, recurrent, visual hallucinations, and parkinsonism. The specificity of a clinical diagnosis of “probable DLB” (two or more core features present) is high at >80%,but sensitivity is generally limited to around 50%. 28 The use of the more lenient, “possible DLB” criteria, which require the presence of only one core feature, increases case detection rates at the cost of reduced diagnostic accuracy and may be useful in clinical practice for screening purposes.29

Table II. Consensus guidelines for the clinical diagnosis of probable and possible dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).27 .

| Central feature |

|

| Core features (two core features essential for a diagnosis of probable DLB, one for possible DLB) |

|

| Supportive features |

|

| Features less likely to be present |

|

Clinical presentation and course of DLB

In general terms, the onset of DLB tends to be insidious, although reports of a period of increased confusion, the onset of hallucinations, or a significant fall may give the impression of a sudden onset. The main differential diagnoses of DLB are AD, vascular dementia, PDD, atypical parkinsonian syndromes, such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), multiple system atrophy (MSA), and corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and also Creutzfeld-Jakob disease (CJD).27 The course of DLB is progressive, with cognitive test scores declining about. 10% per annum, similar to AD.30 Cognitive fluctuations may contribute to large variability in repeated test scores, eg, five Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) points difference over the course of a few days or weeks,31 making it difficult, to be sure of the severity of cognitive impairment by single examination. Survival times from onset, until death are similar to AD,32 although a minority of DLB patients have a very rapid disease course.33,34

The clinical diagnosis of DLB rests on obtaining a detailed history of symptoms from the patient and an informant, mental state examination, appropriate cognitive testing, and neurological examination. Systemic and pharmacological causes of delirium need to be excluded. There are as yet no clinically applicable electrophysiological, genotypic, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) markers to support a DLB diagnosis,7 but neuroimaging investigations may be helpful in supporting the clinical diagnosis. Changes associated with DLB include preservation of hippocampal and medial temporal lobe volume on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)35,36 and occipital hypoperfusion on single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).37,38 Other features, such as generalized atrophy,36 white matter changes,39 and rates of progression of whole brain atrophy,40 appear to be unhelpful in differential diagnosis. Dopamine transporter loss in the caudate and putamen, a marker of nigrostriatal degeneration can be detected by dopaminergic SPECT and, in preliminary studies, has shown specificity and sensitivity of 85% or higher, and may be particularly helpful.41,12

Fluctuating cognition

The profile of neuropsychological impairments in patients with DLB differs from that of AD and other dementia syndromes,43 reflecting the combined involvement of cortical and subcortical pathways and relative sparing of the hippocampus. Patients with DLB perform better than AD on tests of verbal memory,44 but worse on visuospatial performance tasks45 and tests of attention.46 Fluctuations in cognitive function, which may vary over minutes, hours, or days, occur in 50% to 75% of patients, and are associated with shifting levels of attention and alertness. The assessment of fluctuating cognitive impairment poses considerable difficulty to most clinicians and has been repeatedly cited as a reason for low clinical ascertainment of DLB.31,47 Newly proposed methods of assessment may be particularly helpful in this regard. These include caregiverand observer-rated scales.48 Questions such as whether there are episodes when the patient's thinking seems quite clear and then becomes muddled may be useful probes,49,50 although one recent study51 found carers’ reports of fluctuation to be less reliable predictors of DI B diagnosis than more objective questions about daytime sleepiness, episodes of staring blankly, or incoherent speech (Table III). Recording variation in attentional performance using a computer-based test system52 offers an independent method of measuring fluctuation, which is also sensitive to drug treatment effects.53

Table III. Assessing cognitive fluctuation in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). AD, Alzheimer's disease.

| Ferman et al51 |

|

| Four items distinguish DLB and AD |

|

| 3 or 4 features in 83% DLB patients, 12% AD patients, and 0,5% controls |

| Bradshaw et al50 |

|

| Qualitative differences distinguish between fluctuations in DLB and AD |

| Examples of “worst and best period of function” discriminated DLB patients 89% correct; AD patients 4% correct |

Neuropsychiatrie features

Although the expression “noncognitive features of dementia“ is frequently used to describe a multiplicity of symptoms such as apathy, anxiety, delusions, hallucinations, and depression that, are common in dementia, this term implies, probably incorrectly, that such features are independent of cognitive dysfunction. ”Neuropsychiatrie features“54 is a more useful epithet to describe such symptoms, which are particularly common in DLB and which often prompt, referral for clinical assessment.

Visual hallucinations are the most, characteristic neuropsychiatrie feature of DLB, and it. is their persistence55 that helps distinguish them from the episodic perceptual disturbances that occur transiently in dementias of other etiology or during a delirium provoked by an external cause. They are present in 33% of DLB cases at the time of presentation (range 11 %-64%) and occur at some point during the course of the illness in 46% (13%-80%).56 Wellformed, detailed, and animate figures are experienced, provoking emotional responses varying through fear, amusement, or indifference, usually with some insight into the unreality of the episode once it. is over. It. has been suggested that repeated visual hallucinations and associated visual phenomena in DLB are underpinned by disturbances in a lateral frontal cortex–ventral visual stream system,57 emphasizing the cognitive basis of such symptoms. Visual hallucinations in DLB are associated with greater deficits in cortical acetylcholine58 and predict better response to cholinesterase inhibitors.59

Motor parkinsonism

Extrapyramidal signs (EPS) are reported in 25% to 50% of DLB cases at diagnosis, and 75% to 80% of patients develop some EPS during the natural course. The profile of EPS in DLB is generally similar to that in agematched nondcmentcd PD patients25 with greater postural instability and facial impassivity, but less tremor.60 Rate of motor deterioration is about. 10% per annum, similar to PD,61 but Levodopa responsiveness is reduced, possibly due to additional intrinsic striatal pathology and dysfunction.62

Supportive features

Repeated falls, syncope, and transient losses of consciousness

Dementia of any etiology is probably a risk factor for all three of these clinical features and it can be difficult, to clearly distinguish between them. Repeated falls may be due to posture, gait, and balance difficulties, particularly in patients with parkinsonism. Reported fall rates are 28% at. the time of presentation (range 10%-38%) and 37% (22%-50%) at some point during the illness.56 Syncopal attacks in DLB with complete loss of consciousness and muscle tone may represent the extension of LB-associated pathology to involve the brain stem and autonomic nervous system, leading to orthostatic hypotension and/or carotid sinus hypersensitivity, which are more common in DLB than AD or age-matched controls.63 The associated phenomenon of transient episodes of unresponsiveness without loss of muscle tone may represent, one extreme of fluctuating attention and cognition.

Neuroleptic sensitivity

The hypothesis, first made by the Newcastle group, of an abnormal sensitivity to adverse effects of neuroleptic medication was based upon two sets of independent observations. In the first, 67% (14/21) DLB patients received neuroleptics and 57% (8/14) deteriorated rapidly after either receiving them for the first time, or following a dose increase.44 Mean survival time for these 8 patients was reduced to 7.4 months, significantly less than for the 6 patients who had only mild to no adverse reaction (28.5 months) and the 7 never receiving neuroleptics (17.8 months). In the second study, 54% (7/16) neuroleptic-treated DLB patients had neuroleptic sensitivity reactions and their mortality risk, estimated by survival analysis, was increased by a factor of 2.7 .4 Newer atypical antipsychotics used at. low dose may be safer in this regard, but sensitivity reactions have been documented with most and they should be used with great caution.7

Other clinical features

Delusions arc common in DLB, in 56% at. the time of presentation and 65% at some point, during the illness. They are usually based on recollections of hallucinations and perceptual disturbances and consequently often have a fixed, complex, and bizarre content that contrasts with the mundane and often poorly formed persecutory ideas encountered in AD patients, which are based on forget-fulness and confabulation.

Auditory hallucinations occur in 1.9% (range 13%-30%) at presentation and 19% (13% -45%) at. any point. Together with olfactory and tactile hallucinations, these may be important features in some DLB cases and can lead to initial diagnoses of late-onset psychosis64 and temporal lobe epilepsy.44

Sleep disorders have more recently been recognized as common in DLB with daytime somnolence and nocturnal restlessness,65 sometimes as prodromal features. Rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep-wakefulness dissociations may explain several features of DLB that are characteristic of narcolepsy (R.EM sleep behavior disorder, daytime hyper-somnolence, visual hallucinations, and cataplexy).66 Sleep disorders may contribute to the fluctuations typical of DLB and their treatment may improve fluctuations and quality of life.66 Early urinary incontinence has been reported in DLB compared with AD,67 reflecting involvement of autonomic systems. Depressive symptoms are reported in 33% to 50% of DLB cases, a rate higher than in AD and similar to PD,68 and may be related to involvement of monoaminergic brain-stem nuclei.

Management of DLB

General considerations

When dealing with the management, of DLB or FDD patient, it is helpful first, to draw up a problem list of cognitive, psychiatric, and motor disabilities, and to then ask the patient and carer to identify the symptoms that, they find most disabling or distressing and which carry highest priority for treatment.69 The clinician should explain, before any drugs are prescribed, that treatment gains in target symptoms may be associated with worsening of symptoms in other domains. The specific risks of neuroleptic sensitivity reactions (see above) should be mentioned in all cases and it is prudent to mark patient case notes and records with an alert to reduce possibility of inadvertent neuroleptic prescribing, particularly in primary care or emergency room settings.

Nonpharmacological strategics for cognitive symptoms, including explanation, education, reassurance, orientation and memory prompts, attentional cues, and targeted behavioral interventions, are an integral part of the management of DLB, and pharmacological treatment is most successful when prescribed as part of a comprehensive management, approach. Similarly, if a patient with DLB has become acutely confused and psychotic, intercurrent infection and subdural hematoma, in particular, should be actively excluded. It cannot always be assumed that worsening of symptoms is simply part, of the natural fluctuating history of DLB.

Specific treatments

The effectiveness of levodopa on motor symptoms in DLB is thought to be less than in uncomplicated PD, though trial data are lacking. Treatment refractoriness may be related to intrinsic striatal degeneration in DLB and PDD.70 The clinician should aim for the lowest, effective dose of levodopa monotherapy,71 since higher doses or other antiparkinsonian agents, are likely to be associated with increased confusion and hallucinations.

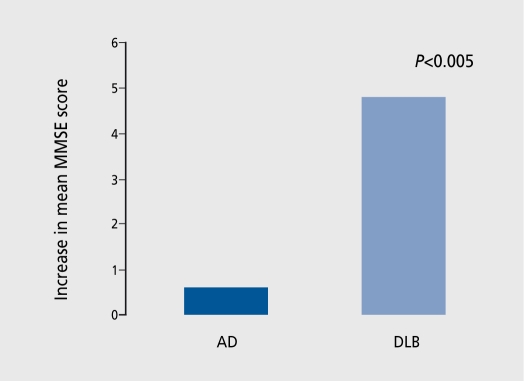

Evidence is accumulating that cholinesterase inhibitor (ChEI) drugs are effective and relatively safe in the treatment of neuropsychiatrie and cognitive symptoms in DLB and PDD, but the number of patients studied is relatively small and larger trials are still needed. In addition to the usual gastrointestinal side effects associated with this class of drug, increased cholinergic activity in DLB patients may cause hypersalivation, rhinorrhea, and lacrimation,72 and exacerbate postural hypotension and falls.73 Improvements are generally reported as greater than those achieved in AD (Figure 2). ,74,75

Figure 2. Cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Twelve Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients and four DLB patients were treated with donepezi! 5 mg/day for 6 months. Nonsignificant difference in changes on BEHAVE-AD (Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale). MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.74 .

Apathy, anxiety, impaired attention, hallucinations, delusions, sleep disturbance, and cognitive changes are the most frequently cited treatment-responsive symptoms in DLB patients treated with ChEIs.3,76,77

These responses are consistent with the loss of basal forebrain and pedunculopontine cholinergic projection neurones and the associated neocortical cholinergic deficits58 that have been identified in DLB. Reduction in temporal choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) is more extensive in those DLB patients with hallucinations than in those without,78 and increased muscarinic receptor density, which probably occurs in response to the marked presynaptic cholinergic deficits, is particularly pronounced in DLB patients with delusions compared with those without.79 DLB patients with visual hallucinations were recently reported to experience greater improvements in performance of attentional tasks following ChEI administration compared with nonhallucinators.59 There are only limited open-label data available of long-term treatment effects,80 which do seem to be sustained, with symptomatic deterioration (sometimes rapid) when treatment is withdrawn.81

Conclusion

As our understanding of the pathological processes underpinning neurodegenerative disorders becomes greater, we might hope that clinical classification and detection of subtypes would become more precise. The example of DLB suggests that this may not be so straightforward. The majority of cases of dementia in older people appear to be related to multiple and overlapping pathologies and this is reflected in considerable clinical heterogeneity. Clinical syndromes such as “probable” DLB or AD are useful predictors of the predominant underlying disease process and are of particular use in planning treatment approaches. The new challenge is to devise better methods of determining the atypical and mixed pathology cases with greater accuracy, acknowledging the existence of clinical and biological overlap.82

REFERENCES

- 1.Rahkonen T., Eloniemi-Sulkava U., Rissanen S., Vatanen A., Viramo P., Sulkava R. Dementia with Lewy bodies according to the consensus criteria in a general population aged 75 years or older. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:720–724. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.6.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lennox G., Lowe J., Landon M., Byrne EJ., Mayer RJ., Godwin-Austen RB. Diffuse Lewy body disease: correlative neuropathology using anti-ubiquitin immunocytochemistry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:1236–1247. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.11.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKeith I., Del-Ser T., Spano PF., et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet. 2000;356:2031–2036. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKeith I., Fairbairn A., Perry R., Thompson P., Perry E. Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. BMJ. 1992;305:673–678. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6855.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballard C., Grace J., McKeith I., Holmes C. Neuroleptic sensitivity in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1998;351:1032–1033. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78999-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKeith I. Report of the Third International Workshop on Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and Parkinson's Disease Dementia (PDD): Diagnosis and Treatment. Newcatle upon Tyne, UK. 2003 Sep [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKeith I., Mintzer J., Aarsland D., et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosaka K., Yoshimura M., Ikeda K., Budka H. Diffuse type of Lewy body disease: progressive dementia with abundant cortical Lewy bodies and senile changes of varying degree―a new disease? Clin Neuropathol. 1984;3:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibb WRG., Esiri MM., Lees AJ. Clinical and pathological features of diffuse cortical Lewy body disease (Lewy body dementia). Brain. 1987;110:1131–1153. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.5.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen L., Salmon D., Galasko D., et al. The Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical and pathologic entity. Neurology. 1990;40:1–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry RH., Irving D., Blessed G., Fairbairn A., Perry EK. Senile dementia of Lewy body type. A clinically and neuropathologically distinct form of Lewy body dementia in the elderly. J Neurol Sci. 1990;95:119–139. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90236-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrne EJ., Lennox G., Godwin-Austen RB., et al. Dementia associated with cortical Lewy bodies. Proposed diagnostic criteria. Dementia. 1991;2:283–284. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding AJ., Halliday GM. Cortical Lewy body pathology in the diagnosis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;102:355–363. doi: 10.1007/s004010100390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gómez-Tortosa E., Newell K., Irizarry MC., Albert M., Growdon JH., Hyman BT. Clinical and quantitative pathological correlates of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 1999;53:1284–1291. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuel W., Galasko D., Masliah E., Hansen LA. Neocortical Lewy body counts correlate with dementia in the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:44–52. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry EK., Piggott MA., Johnson M., et al. Neurotransmitter correlates of neuropsychiatrie symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies. In: Bedard MA, Agid Y, Chouinard S, Fahn S, Korczyn AD, Lesperance P, eds. Mental and Behavioral Dysfunction in Movement Disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2003:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton RL. Lewy bodies in Alzheimer's disease: a neuropathological review of 145 cases using α-synuclein imrnunohistochemistry. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2000.tb00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lippa CF., McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies improving diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2003;60:1571–1572. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000066054.20031.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merdes AR., Hansen LA., Jeste DV., et al. Influence of Alzheimer pathology on clinical diagnostic accuracy in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2003;60:1586–1590. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000065889.42856.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aarsland D., Andersen K., Larsen JP., Lolk A., Kragh-Sorensen P. Prevalence and characteristics of dementia in Parkinson disease―an 8-year prospective study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:387–392. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emre M. Dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aarsland D., Andersen K., Larsen JP., Lolk A., Kragh-Sorensen P. Prevalence and characteristics of dementia in Parkinson disease―an 8-year prospective study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:387–392. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballard CG., Aarsland D., McKeith IG., et al. Fluctuations in attention―PD dementia vs DLB with parkinsonism. Neurology. 2002;59:1714–1720. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036908.39696.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aarsland D., Ballard C., Larsen JP., McKeith I. A comparative study of psychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with and without dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:528–536. doi: 10.1002/gps.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aarsland D., Ballard C., McKeith I., Perry RH., Larsen JP. Comparison of extrapyramidal signs in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13:374–379. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKeith IG., Burn D. Spectrum of Parkinson's disease, Parkinson's dementia, and Lewy body dementia. In: DeKosky ST, ed. Neurologic Clinics. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 2000:865–883. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKeith IG., Galasko D., Kosaka K., et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): Report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47:1113–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Litvan I., Bhatia KP., Burn DJ., et al. SIC Task Force Appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for parkinsonian disorders. Mov Disord. 2003;18:467–486. doi: 10.1002/mds.10459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luis CA., Barker WW., Gajaraj K., et al. Sensitivity and specificity of three clinical criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies in an autopsy-verified sample. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:526–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballard C., O'Brien J., Morris CM., et al. The progression of cognitive impairment in dementia with Lewy bodies, vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:499–503. doi: 10.1002/gps.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mega MS., Masterman DL., Benson F., et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies: reliability and validity of clinical and pathologic criteria. Neurology. 1996;47:1403–1409. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker Z., Allen RL., Shergill S., Mullan E., Katona CLE. Three-year survival in patients with a clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:267–273. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(200003)15:3<267::aid-gps107>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstrong TP., Hansen LA., Salmon DP., et al. Rapidly progressive dementia in a patient with the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41:1178–1180. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.8.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez 0L., Wisniewski S., Hamilton RL., Becker JT., Kaufer Dl., DeKosky ST. Predictors of progression in patients with AD and Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000;54:1774–1779. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.9.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barber R., Gholkar A., Scheltens P., Ballard C., McKeith IG., O'Brien JT. Medial temporal lobe atrophy on MRI in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 1999;52:1153–1158. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.6.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barber R., Ballard C., McKeith IG., Gholkar A., O'Brien JT. MRI volumetric study of dementia with Lewy bodies. A comparison with AD and vascular dementia. Neurology. 2000;54:1304–1309. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.6.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lobotesis K., Fenwick JD., Phipps A., et al. Occipital hypoperfusion on SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies but not AD. Neurology. 2001;56:643–649. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colloby SJ., Fenwick JD., Williams ED., et al. A comparison of MmTc-HMPA0 SPECT changes in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease using statistical parametric mapping. Eur J Nucl Med. 2002;29:615–622. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barber R., Gholkar A., Scheltens P., Ballard C., McKeith IG., O'Brien JT. MRI volumetric correlates of white matter lesions in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:911–916. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200010)15:10<911::aid-gps217>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Brien JT., Paling S., Barber R., et al. Progressive brain atrophy on serial MRI in dementia with Lewy bodies, AD, and vascular dementia. Neurology. 2001;56:1386–1388. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker Z., Costa DC., Ince P., McKeith IG., Katona CLE. In-vivo demonstration of dopaminergic degeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet. 1999;354:646–647. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Brien JT., Colloby SJ., Fenwick J., et al. Dopamine transporter loss visualised with FP-CIT SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:919–925. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.6.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gollerton D., Burn D., McKeith I., O'Brien J. Systematic review and metaanalysis show that dementia with Lewy bodies is a visual-perceptual and attentional-executive dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16:229–237. doi: 10.1159/000072807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKeith IG., Perry RH., Fairbairn AF., Jabeen S., Perry EK. Operational criteria for senile dementia of Lewy body type (SDLT). Psychol Med. 1992;22:911–922. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700038484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker Z., Allan RL., Shergill S., Katona CLE. Neuropsychological performance in Lewy body dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:156–158. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sahgal A., Galloway PH., McKeith IG., Edwardson JA., Lloyd S. A comparative study of attentional deficits in senile dementias of Alzheimer and Lewy body types. Dementia. 1992;3:350–354. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530340059019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Litvan I., Maclntyre A., Goetz CG., et al. Accuracy of the clinical diagnoses of Lewy body disease, Parkinson's disease, and dementia with Lewy bodies. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:969–978. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.7.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker MP., Ayre GA., Cummings JL., et al. The Clinician Assessment of Fluctuation and the One Day Fluctuation Assessment Scale. Two methods to assess fluctuating confusion in dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:252–256. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ballard CG., Mohan RNC., Patel A., Bannister C. Idiopathic clouding of consciousness―do the patients have cortical Lewy body disease? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1993;8:571–576. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bradshaw J SM., Hopwood M., Anderson V., Brodtmann A. Fluctuating cognition in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease is qualitatively distinct. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:382–387. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2002.002576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferman T., Smith GE., Boeve BF., et al. DLB fluctuations: specific features that reliably differentiate from AD and normal aging. Neurology. 2004;62:181–187. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walker MP., Ayre GA., Cummings JL., et al. Quantifying fluctuation in dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Neurology. 2000;54:1616–1624. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.8.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wesnes KA., McKeith IG., Ferrara R., et al. Effects of rivastigmine on cognitive function in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised placebo-controlled international study using the Cognitve Drug Research computerised assessment system. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;13:183–192. doi: 10.1159/000048651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cummings JL., Mega M., Gray K., Rosenberg-Thompson S., Carusi DA., Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatrie Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McShane RH., Esiri MM., Joachim C., Smith AD., Jacoby RJ. Prospective evaluation of diagnostic criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19(4S):S204. [Google Scholar]

- 56.McKeith IG. Dementia with Lewy bodies: clinical and pathological diagnosis. Alzheimer's Rep. 1998;1:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collerton D. Why do people see thing that are not there? Brain Behav Sci. 2004. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perry EK., McKeith I., Thompson P., et al. Topography, extent, and clinical relevance of neurochemical deficits in dementia of Lewy body type, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;640:197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McKeith IG WK., Perry E., Ferrara R. Hallucinations predict attentional improvements with rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18:94–100. doi: 10.1159/000077816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burn DJ., Rowan EN., Minett T., et al. Extrapyramidal features in Parkinson's disease with and without dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies: a crosssectional comparative study. Mov Disord. 2003;18:884–889. doi: 10.1002/mds.10455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ballard C., O'Brien J., Swann A., et al. One-year follow-up of Parkinsonism in dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11:219–222. doi: 10.1159/000017240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duda JE., Giasson Bl., Mabon ME., Lee VMY., Trojanowski JQ. Novel antibodies to synuclein show abundant striatal pathology in Lewy body diseases. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:205–210. doi: 10.1002/ana.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ballard C., Shaw F., McKeith I., Kenny RA. High prevalence of neurovascular instability in neurodegenerative dementias. Neurology. 1998;51:1760–1762. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Birkett DP., Desouky A., Han L., Kaufman M. Lewy bodies in psychiatric patients, int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1992;7:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grace J., Walker MP., McKeith IG. A comparison of sleep profiles in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:1028–1033. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1028::aid-gps227>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boeve B., Silber M., Ferman T., Lucas J., Parisi J. Association of REM sleep behavior disorder and neurodegenerative disease may reflect an underlying synucleinopathy. Mov Disord. 2001;16:622–630. doi: 10.1002/mds.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Del-Ser T., Munoz DG., Hachinski V. Temporal pattern of cognitive decline and incontinence is different in Alzheimer's disease and diffuse Lewy body disease. Neurology. 1996;46:682–686. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klatka LA., Louis ED., Schiffer RB. Psychiatric features in diffuse Lewy body disease: findings in 28 pathologically diagnosed cases. Neurology. 1996;46:A180. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barber R., Panikkar A., McKeith IG. Dementia with Lewy bodies: diagnosis and management. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:S12–S18. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200112)16:1+<::aid-gps562>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duda JE., Giasson Bl., Mabon ME., Lee VMY., Trojanowski JQ. Novel antibodies to synuclein show abundant striatal pathology in Lewy body diseases. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:205–210. doi: 10.1002/ana.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Burn DJ., McKeith IG. Current treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies and dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2003;18:S72–S79. doi: 10.1002/mds.10566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas AJ., Burn DJ., Rowan EN., et al. Efficacy of donepezil in Parkinson's disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Mov Disord. 2003. Submitted. doi: 10.1002/gps.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McLaren AT., Allen J., Murray A., Ballard CG., Kenny RA. Cardiovascular effects of donepezil in patients with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;15:183–188. doi: 10.1159/000068781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Samuel W., Caligiuri M., Galasko D., et al. Better cognitive and psychopathologic response to donepezil in patients prospectively diagnosed as dementia with Lewy bodies: a preliminary study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:794–802. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200009)15:9<794::aid-gps178>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aarsland D., Laake K., Larsen JP., Janvin C. Donepezil for cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: a randomised controlled study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:708–712. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaufer Dl., Catt KE., Lopez 0L., DeKosky ST. Dementia with Lewy bodies: response of delirium-like features to donepezil. Neurology. 1998;51:1512. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reading PJ., Luce AK., McKeith IG. Rivastigmine in the treatment of parkinsonian hallucinosis. Neurology. 2002;58(suppl 3):A380. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perry EK., Marshall E., Perry RH., et al. Cholinergic and dopaminergic activities in senile dementia of Lewy body type. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1990;4:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ballard C., Piggott M., Johnson M., et al. Delusions associated with elevated muscarinic binding in dementia with Lewy bodies. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:868–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grace J., Daniel S., Stevens T., et al. Long-term use of rivastigmine in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: an open-label trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2001;13:199–205. doi: 10.1017/s104161020100758x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Minett TSC., Thomas A., Wilkinson LM., et al. What happens when donepezil is suddenly withdrawn? An open label trial in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:988–993. doi: 10.1002/gps.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McKeith IG. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and other difficult diagnoses. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16:123–127. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]