Abstract

Diurnal variation of depressive symptoms appears to be part of the core of depression. Yet longitudinal investigation of an individual's pattern regularity, relation to clinical state, and clinical improvement reveals little homogeneity. Morning lows, afternoon slump, evening worsening - all can occur during a single depressive episode. Mood variability, or the propensity to produce mood swings, appears to be the characteristic that most predicts capacity to respond to treatment. Laboratory studies have revealed that mood, like physiological variables such as core body temperature, is regulated by a circadian clock interacting with the sleep homeostat. Many depressed patients, particularly bipolar patients, show delayed sleep phase (late chronotype). Even small shifts in the timing and duration of sleep affect mood state (sleep deprivation and sleep phase advance have an antidepressant effect). The implications for treatment are to stabilize mood state by enhancing synchronization of the sleep-wake cycle with the biological clock (eg, with light therapy).

Keywords: major depressive disorder, mood, circadian rhythm, sleep regulation, sleep deprivation, synchronization

Abstract

La variación diurna de los síntomas depresivos parece ser parte nuclear de la depresión. Actualmente la investigatión longitudinal del patrón de un sujeto acerca de la regularidad, la relación con el estado clínico y la mejoria clínica revela escasa homogeneidad. En la mañana está deprimido, en la tarde se acentúa el bajón y en la noche empeora aun más; todo esto puede ocurrir durante cualquier episodio depresivo. La variabilidad del ánimo o la propensión a producir un viraje de éste parece ser la característica que mejor predice la capatidad de respondera un tratamiento, Los estudios de laboratorio han revelado que el ánimo, al igual que variables fisiológicas como la temperatura corporal central, es regulado por un reloj circadiano que interactúa con el homeostato del sueño, Muchos pacientes depresivos, en especial los bipolares, presentan retardo de la fase del sueño (cronotipo retrasado), Incluso pequehos cambios en el ritmo y duración del sueño afectan el estado de ánimo (la privación de sueño y el avance de fase del sueño tienen un efecto antidepresivo). Las consecuencias para el tratamiento se traducen en estabilizar el estado de ánimo mediante el aumento de la sincronización del ciclo sueño-vigilia con el reloj biológico (por ej. con luminoierapia).

Abstract

Les variations diurnes des symptômes dépressifs semblent être au coeur de la dépression, La recherche longitudinale d'un schéma individuel, incluant la régularité, la relation à l'état clinique et les améliorations symptomaiiques ne met à ce jour en évidence que peu d'homogénéité. Ralentissement matinal, baisse dans l'après-midi, aggravation en soirée, tout peut survenir lors d'un simple épisode dépressif, La variabilité de l'humeur, ou la propension à changer d'humeur, semble être le critère qui prédit le mieux la capacité à répondre au traitement. Des études de laboratoire ont montré que l'humeur, comme certaines variables physiologiques telle la température corporelle centrale, est régulée par une horloge circadienne qui interagit avec l'homéostat du sommeil. De nombreux patients dépressifs, en particulier les patients bipolaires, présentent un retard de phase pour le sommeil (chronotype retardé). Même de faibles décalages dans la programmation et la durée du sommeil influent sur l'humeur (privation de sommeil et avance de phase ont un effet antidépresseur). Les conséquences de ces résultais sur le plan thérapeutique sont de chercher à stabiliser l'humeur en augmentant la synchronisation du cycle veille-sommeil avec l'horloge biologique (par exemple, avec la luminothêrapie).

Diurnal variation of depressive symptoms (DV) with early-morning worsening is considered a core feature of melancholia in both DSM-1V and I CD criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD).This is not the only pattern, however: an afternoon slump or evening worsening also occurs. Decades of research have sought to clarify the source and significance of this clinically striking phenomenon. Yet, although depression is often linked with visible mood swings, a clear picture of what diurnal variation means in terms of diagnostic categories and treatment prediction still has not. emerged. In fact, the closer one looks, the more complex DV becomes.

Circadian biologists have determined that nearly everything we can measure undergoes changes across the 24-hour day. Rhythms in hormones such as Cortisol and melatonin, in physiologic function such as core body temperature and heart rate, are perhaps obvious. An important, step forward in understanding more subjective or complex cognitive processes has been the two-process model of sleep-wake regulation, which postulates a circadian pacemaker interacting with the sleep homeostat to determine both nocturnal sleep architecture and daytime vigilance.1 Many behaviors, ranging from subjective alertness and mood to higher cognitive functions, show an underlying circadian rhythm modulated by the duration of prior wakefulness. It is therefore perhaps useful to consider what normal daily variations of mood look like before attempting to understand psychopathology.

How can DV be measured?

Comparison between global self-ratings, an itemized prospective observer-rating, and the retrospective item on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale showed rather poor agreement.2 In spite of this, many studies have obtained reasonable results (considering that this is a subjective judgment) from the practicable method of simple self -ratings two or more times a day. In this way it became clear that, contrary to expectations, when depressed inpatients recorded daily mood changes during their entire stay, not only did the frequency of diurnal variation vary between subjects, but it was also very irregular.3

The Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect. (NA) Schedule provides more differentiated psychometric information. The PA scale reflects the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, excited, active, and determined, whereas the NA scale reflects subjective distress that subsumes a broad range of aversive affects including fear, nervousness, guilt, and shame. Is depression too much negative affect - or too little positive affect? Repeated measurements of NA and PA in daily life showed that depressed individuals increase PA levels during the day, with maximum values later than those of controls:4 In contrast, NA exhibited a more pronounced diurnal rhythm in depressed persons, with more moment-tomoment, variability.

Circadian rhythm of mood in healthy subjects

Diurnal mood swings are present in nonclinical individuals. Persons whose mood was low had a DV pattern showing increased PA in the evening relative to the morning, but with low amplitude.5 Another study in healthy subjects showed that, the evening-worse pattern was associated with many neurotic features, depressive mood, anxiety, and a cognitive style indicative of hopelessness.6 Thus, DV occurs in many individuals in every day life, with a variety of patterns analogous to those found in MDD.

It is more difficult to demonstrate that, mood, like core body temperature or Cortisol, follows an endogenous circadian rhythm. Two stringent protocols have been developed to study the human circadian system: the constant routine (whereby subjects spend 25 to 40 hours awake, supine, in dim light, with equally spaced isocaloric snacks, in order to unmask the underlying circadian oscillation) and the forced desynchrony protocol (whereby subjects live on a longer or shorter than 24-hour “day” so that their sleep-wake cycle is desynchronized from the underlying circadian pacemaker).

In healthy subjects, a number of constant, routine studies have shown that, mood follows a circadian rhythm with lowest values around the time of the core body temperature minimum. For example, PA exhibited a significant 24hour rhythm in parallel with the circadian temperature rhythm, whereas NA did not.7 Our group has recently documented a circadian rhythm of subjective well-being in a constant routine, even when the sleep homeostatic component was varied by regular naps (low sleep pressure) or total sleep deprivation (high sleep pressure).8 Overall, well-being was worse during the high sleep pressure condition, in older subjects, and in women. Thus, both age and gender modulate circadian and sleep-wake homoeostatic contributions to subjective well-being.

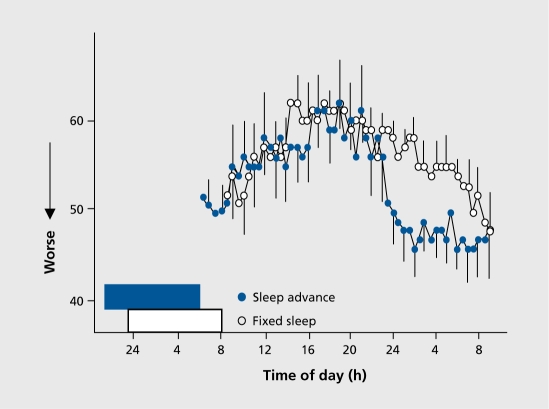

We have an experimental example of how a slight shift in sleep timing can modify mood even in healthy subjects. In this controlled study, carried out in near-darkness, sleep timing was either slowly advanced by 20 minutes per day over 6 days or kept constant.9 The protocol ensured that, sleep was shifted 2 hours earlier with minimum shifting of the underlying clock. 'ITiis slight misalignment changed the usual circadian rhythm of mood measured in a constant, routine so that mood suddenly dropped and remained low the entire night (Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Influence of a 2-h phase advance of sleep in darkness on the circadian rhythm of mood (100-mm visual analogue scale) as measured under a 26-hour constant routine protocol (N=10 healthy young men, crossover design): mood dropped suddenly in the evening and remained low throughout the night. Redrawn from ref 9.

In forced dcsynchrony, the circadian and sleep homeostatic contributions to mood state at. any given time of day can be mathematically separated. A milestone study demonstrated significant variation of mood with circadian phase, without any reliable main effect of the duration of prior wakefulness.10 However, there was a significant, interaction between circadian and wake-dependent fluctuations. Depending on the circadian phase, mood improved, deteriorated, or remained stable with the duration of prior wakefulness. If this can happen in healthy subjects, depressive patients may be even more vulnerable. The findings have important implications for understanding (and treating) depressive mood swings.

Circadian rhythm of mood in MDD

An early study under ambulatory conditions over 2 weeks compared circadian rhythms in drug-free MDD patients before and after recover}' with healthy controls.“ Lowest, circadian mood occurred around the time of awakening during depression, several hours later than after remission or in normal controls (lowest in the middle of the night). The circadian variation of motor activity, body temperature, and urinary potassium was reduced during depression.12 A hint for a phase delay and lowered circadian amplitude?

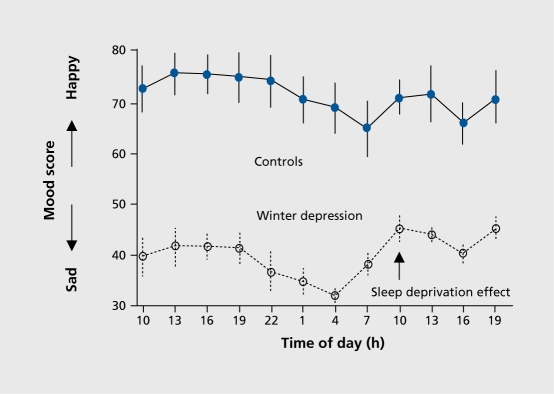

In a 40-hour constant, routine study of seasonal affective disorder, the circadian rhythm of mood in controls could be contrasted with the overall lower mood in the depressed patients (Figure 2.). What is clearly seen in the latter group is the mood-enhancing effect, of sleep deprivation during the second half of the constant routine.

Figure 2. Mood changes (100-mm visual analogue scale) across a 40-hour constant routine protocol (= total sleep deprivation) in control middle-aged women (N=8) and women with winter depression (N=11). Both groups show a circadian rhythm; in addition, patients improve on the second day after sleep deprivation. (Wirz-Justice, unpublished data).

The only study so far of MDD in forced desynchrony has been carried out in patients with seasonal affective disorder (during a winter depressive episode, after recovery with light therapy, and in summer) compared with controls (winter and summer).13 No significant differences were observed in circadian period or the timing of the circadian temperature minimum (i e, biological clock function was normal). In both groups, mood showed both sleep-wake cycle and pacemaker related components. Figure 3. demonstrates the interaction in healthy subjects.13,14 The raw dayby-day data do not appear to have any predictable pattern. Dissection into the two components reveals an astonishing regularity underlying the variability in subjective mood state. The sleep-wake cycle dependent component, is characterized by poor mood just on waking, improvement, over the next. 3 hours, and thereafter an exponential decline. The clock-related variation is also low on awakening, but improves during the day and declines throughout the night in a circadian pattern.

Figure 3. Course of mood as assayed by the Adjective Mood Scale completed at 2-hour intervals throughout six 20-h days (forced desynchrony protocol) in healthy subjects. Analysis of the sleepwake and circadian clock-related components reveals the strong physiological components underlying subjective mood. Redrawn from ref 14.

These data provide evidence for circadian underpinnings to mood state (independent of the many other factors that of course modulate well-being from moment to moment), and that, timing and duration of sleep itself can modify mood. It. is within this context that the inconclusive, though informative, studies of DV in MDD should be re-evaluated.

DV as a phenomenon

DV appears not to be pathognomonic for the diagnosis of .MDD, nor specific for clinical state.15,16 However, patients who did not have mood swings when healthy developed DV when hospitalized for depression, predominantly the classical form with improvement, toward evening.15 The older psychiatric literature describes lack of mood variability during the most, severe melancholic depression, the return of DV being considered as the first sign of being on the road to improvement. 'ITie large cohort of patients in the STAR*D study were examined in detail for different, patterns of DV.“ DV was reported in 22.4%: of these, 31.9% reported morning worsening, 19.5% afternoon, and 48.6% evening worsening. Melancholic symptom features were associated with DV, regardless of pattern.

Using a neuropsychological test battery, the morning pattern of impairment in the melancholies was comprehensive, affecting attention and concentration/working memory, episodic memory, reaction time, and speed of simultaneous match to sample.18 Significantly improved neuropsychological function was seen in the melancholic patients in the evening, in line with diurnal improvement in mood. Some functions remained impaired in the evening compared with controls; others improved. Another study also found that complex tests of executive function were sensitive measures of DV19

Mood variability

'ITic concept of mood variability, rather than any specific pattern of mood change, has arisen from long-term studies.20 Women with premenstrual syndrome had greater mood variability than normal subjects. Patients with borderline personality disorder also revealed a high degree of mood variability, but random in nature from one day to the next.20 'This suggests that mechanisms regulating mood stability may differ from those regulating overall mood state.

Dynamic patterns of mood variation were revealed using complex time series analyses of self-assessments of anxiety and depression for each hour awake during a 30-day period.21 Controls displayed circadian rhythms with underlying chaotic variability, whereas depressed patients no longer had circadian rhythms, but. retained chaotic dynamics.

Days with no DV or with typical DV (morning low, afternoon/evening high) occurred with similar frequency in both melancholic patients and controls.22 In other words, circadian mood variations vary substantially inter- and intraindividually. Interesting are the attributions: melancholic patients experience spontaneous mood variations as uninfluenceable, whereas healthy controls consider them almost exclusively related to their own activities and/or external circumstances.22

DV and chronotype

Many of the above findings of worse morning mood suggest, a late chronotype in MDD. Three new studies have looked at large populations of bipolar patients, and replicably found a predisposition for late chronotypes.23-25

Additionally, individuals with higher depression scores are more likely to be late chronotypes.25 One of the characteristics of circadian rhythms is that the lower the strength of synchronizing agents (zeitgebers), the later they drift. Less light, exposure in winter could underline the reported delayed chronotype in winter depression.26 Could the lower lifestyle regularity and activity level indices (as codified in the Social Rhythm Metric) in bipolar disorder patients compared with controls be an indication of such a diminution of zeitgebers?27 In addition, the timing of five, mostly morning, activities was phase-delayed in patients not only compared with control subjects but with themselves when well.27

Sleep deprivation

Discovery of the rapid and potent antidepressant response to sleep deprivation (total or partial in the second half of the night.) provided an essential link between depressive mood and the timing and amount of sleep. Indeed, it was clear that total or partial sleep deprivation was a characteristic of spontaneous switches out. of depression.28 Patients were more likely to switch from depression into mania or hypomania during the daytime hours and from mania/hypomania into depression during sleep.29

A number of studies thus investigated the relationship between DV and clinical response. Sleep deprivation rcsponders manifested DV more often than nonrcsponders, with a pattern of improved mood in the evening.30,31 Patients with marked DV responded better to sleep deprivation than those with little. Later, the question was asked whether the propensity to produce DV or the actual mood course on the day before sleep deprivation determined clinical response.32 For each patient six sleep deprivation nights were scheduled: two after days with a positive mood course, two after a negative mood course, and two after days without a diurnal change of mood. This strategy allowed within-patient comparison of responses. It was found that patients vary largely in the occurrence of diurnal variations of mood. The propensity to produce DV either in terms of frequency or amplitude was positively correlated with the response to sleep deprivation. With-in patients no differences were found in responses to sleep deprivation applied after days with (positive or negative) or without. DV. Further investigations revealed that, mood variability measures rather than average daily mood improvement, correlated with the response to sleep deprivation.3

The findings with sleep deprivation suggested that DV could be a potential predictor for a patient's likelihood to respond to different therapies eg, antidepressants.33 Indeed, a recent study has gone into some detail: patients with reversed DV had a poorer response to a serotonergic antidepressant, were less likely to have bipolar II disorder, had a higher tryptophan: large neutral amino acid ratio and had different, allele frequencies of the polymorphisms in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter.34 These findings raise the possibility of serotonergic influence on DV, and that the symptom of evening mood worsening is of relevance to antidepressant prescribing.

In healthy controls, sleep deprivation usually has little effect on mood, rather simply increasing sleepiness and irritability. Separating subjects according to chronotype shows some differences, however, in response to sleep deprivation.35 Early chronotypes increased, and late chronotypes decreased their depressive mood score.

Diurnal variations in physiology and biochemistry

Many variables considered of interest for the etiology of major depression have been investigated over the 24-hour day. Some of the earliest and most consistent findings have been the elevated nocturnal body temperature in depression ,12,36,37 and a circadian rhythm of Cortisol with loss of the normally occurring early evening nadir.38 The pineal hormone melatonin often, but not always, shows a lower nocturnal peak in depressed patients. Cerebrospinal fluid hypocretin-1 levels have a low amplitude rhythm in controls which is even less in depression.39 Morning elevations of plasma IL-6 and a reversal of its circadian rhythm has been found in MDD patients, in the absence of hypercortisolism.40 These are but a few examples, that indicate alterations in circadian organization. The majority of results are consistent with dampened diurnal variations in depression (diminished amplitude), and sometimes a phase advance, independent of whether the variable had a higher or lower mean value than controls.

Only a few studies have attempted to look at. correlations with DV IL-6 levels correlated significantly with mood ratings.40 Depressed patients with evening mood improvements had smaller increases in regional cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (rCMRglc) during evening relative to morning in lingual and fusiform cortices, midbrain reticular formation, and locus coeruleus and greater increases in rCMRglc in parietal and temporal cortices, compared with healthy subjects.41 Interestingly, evening mood improvements were associated with increased metabolic activity in ventral limbic-paralimbic, parietal, temporal, and frontal regions and in the cerebellum, 'this increased metabolic pattern was considered to reflect partial normalization of primary and compensatory neural systems involved in affect, production and regulation.41

Another intriguing finding is that patients with high DV tended to show low circadian rhythmicity in skin body temperature, whereas patients with low DV tended toward a higher diurnal variation in skin body temperature.42 Again an indirect, reflection of lowered circadian amplitude permitting mood variability to emerge?

What is important?

It is axiomatic (for a chronobiologist) that, stable timing between internal rhythms such as temperature and sleep with respect to the external day-night cycle is crucial for well-being. To establish stable phase relationships two characteristics are important: adequate amplitude of the circadian pacemaker (a good endogenous rhythm), and adequate strength of the zeitgeber (good exogenous 24-hour input signals). The scattered evidence suggest that it is these two characteristics that are disturbed in MDD. Internal rhythms are flatter - thus prone to desynchronization. The lowered strength of zeitgebers in depressive patients (whether social or light exposure) also permits rhythms to drift out of sync and show greater variability from day to day.

That mood changes across the day is normal. DV is of itself not pathologic. However, DV research suggests that any misalignment of internal clock, sleep, and external light-dark cycle can induce mood changes, particularly in vulnerable individuals. The propensity for mood variability and extreme mood swings in MDD, even if not ) predictable, reflects this underlying instability. The lack of a single pattern or replicable correlation with clinical ) state means that DV is not a hard biological marker - this is frustrating for the clinicians. But we have clues. Even moderate changes in the timing of the sleep-wake cycle may have profound effects on subsequent mood (for better or for worse). Sleep deprivation or sleep phase advance is antidepressant in MDD. DV is indeed a core symptom of depression, but an elusive one when it needs; to be carefully defined. Thus, perhaps we should not try 5 to hunt down the chimera - its fugitive presence is sufficient for a chronobiologist. to suggest therapeutic consequences. Any manipulation that helps stabilize circaf dian phase relationships - light, social structures, meal t times, exercise, correctly timed medication - will have a 1 positive effect on mood.

Selected abbreviations and acronyms

- DV

diurnal variation

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- PA

positive affect

- NA

negative affect

REFERENCES

- 1.Borbély AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. . Hum Neurobiol. 1982;1:195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leibenluft E, Noonan BM, Wehr TA. Diurnal variation: reliability of measurement and relationship to typical and atypical symptoms of depression. . J Affect Disord. 1992;26:199–204. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordijn MCM, Beersma DG, Bouhuys AL, Reinink E, Van den Hoofdakker RH. A longitudinal study of diurnal mood variation in depression; characteristics and significance. . J Affect Disord. 1994;31:261–273. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peeters F, Berkhof J, Delespaul P, Rottenberg J, Nicolson NA. Diurnal mood variation in major depressive disorder. . Emotion. 2006;6:383–391. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray G. Diurnal mood variation in depression: a signal of disturbed circadian function? . J Affect Disord. 2007;102:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rusting CI, Larsen RJ. Diurnal patterns of unpleasant mood: associations with neuroticism, depression, and anxiety. . J Pers. 1998;66:85–103. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray G, Allen NB, Trinder J. Mood and the circadian system: investigation of a circadian component in positive affect. . Chronobiol Int. 2002;19:1151–1169. doi: 10.1081/cbi-120015956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birchler Pedross A, Schroder C, Wirz-Justice A, Cajochen C. Circadian modulation in subjective well-being under high and low sleep pressure conditions: effects of age and gender. . Swiss Med Wkl. 2008;138(suppl 162):3S. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danilenko KV, Cajochen C, Wirz-Justice A. Is sleep per se a zeitgeber in humans? . J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18:170–178. doi: 10.1177/0748730403251732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boivin DB, Czeisler CA, Dijk DJ, et al. Complex interaction of the sleepwake cycle and circadian phase modulates mood in healthy subjects. . Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:145–152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140055010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Zerssen D, Doerr P, Emrich HM, Lund R, Pirke KM. Diurnal variation of mood and the Cortisol rhythm in depression and normal states of mind. . Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1987;237:36–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00385665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Zerssen D, Barthelmes H, Dirlich G, et al. Circadian rhythms in endogenous depression. . Psychiatry Res. 1985;16:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(85)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koorengevel KM, Beersma DGM, Den Boer JA, van den Hoofdakker RH. Mood regulation in seasonal affective disorder patients and healthy controls studied in forced desynchrony. . Psychiatry Res. 2003;117:57–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Hoofdakker RH. Total sleep deprivation: clinical and theoretical aspects. In: Honig AV, van Praag HM, eds. . Depression: Neurobiological, Psychopathological and Therapeutic Advances. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons . 1997:564–589. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graw P, Hole G, Gastpar M. Diurnal variations in hospitalised depressive patients during depression and when healthy. . Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1980;228:329–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00343614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fähndrich E, Haug HJ. Diurnal variations of mood in psychiatric patients of different nosological groups. . Neuropsychobiol. 1989;20:141–144. doi: 10.1159/000118488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris DW, Rush AJ, Jain S, et al. Diurnal mood variation in outpatients with major depressive disorder: implications for DSM-V from an analysis of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression Study data. . J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1339–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moffoot AP, O'Carroll RE, Bennie J, et al. Diurnal variation of mood and neuropsychological function in major depression with melancholia. . J Affect Disord. 1994;32:257–269. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porterfield T, Cook M, Deary IJ, Ebmeier KP. Neuropsychological function and diurnal variation in depression. . J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1997;19:906–913. doi: 10.1080/01688639708403771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowdry RW, Gardner DL, O'Leary KM, Leibenluft E, Rubinow DR. Mood variability: a study of four groups. . Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1505–1511. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katerndahl D, Ferrer R, Best R, Wang CP. Dynamic patterns in mood among newly diagnosed patients with major depressive episode or panic disorder and normal controls. . Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:183–187. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wefelmeyer T, Kuhs H. Diurnal mood variation in melancholic patients and healthy controls. . Psychopathol. 1996;29:184–192. doi: 10.1159/000284990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansour H, Wood J, Logue T, et al. Circadian phase variation in bipolar I disorder. . Chronobiol int. 2005;22:571–584. doi: 10.1081/CBI-200062413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn YM, Chang J, Joo YH, Kim SC, Lee KY, Kim YS. Chronotype distribution in bipolar 1 disorder and schizophrenia in a Korean sample. . Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:271–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood J, Birmaher B, Axelson D, et al. Replicable differences in preferred circadian phase between bipolar disorder patients and control individuals. . Psychiatry Res. 2008 In press doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elmore SK, Dahl K, Avery DH, Savage MV, Brengelmann GL. Body temperature and diurnal type in women with seasonal affective disorder. . Health Care Women Int. 1993;14:17–26. doi: 10.1080/07399339309516023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashman SB, Monk TH, Kupfer DJ, et al. Relationship between social rhythms and mood in patients with rapid cycling bipolar disorder. . Psychiatry Res. 1999;86:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wehr TA, Wirz-Justice A. Circadian rhythm mechanisms in affective illness and in antidepressant drug action. . Pharmacopsychiatria . 1982;12:31–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1019506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldman-Naim S, Turner EH, Leibenluft E. Diurnal variation in the direction of mood switches in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. . J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:79–84. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reinink E, Bouhuys AL, Wirz-Justice A, van den Hoofdakker RH. Prediction of the antidepressant response to total sleep deprivation by diurnal variation of mood. . Psychiatry Res. 1990;32:113–124. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(90)90077-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haug HJ. Prediction of sleep deprivation outcome by diurnal variation of mood. . Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90050-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinink E, Bouhuys AL, Gordijn MCM, Van Den Hoofdakker RH. Prediction of the antidepressant response to total sleep deprivation of depressed patients: longitudinal versus single day assessment of diurnal mood variation. . Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34:471–481. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wirz-Justice A, Puhringer W, Hole G. Response to sleep deprivation as a predictor of therapeutic results with antidepressant drugs. . Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:1222–1223. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.9.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joyce PR, Porter RJ, Mulder RT, et al. Reversed diurnal variation in depression: associations with a differential antidepressant response, tryptophan: large neutral amino acid ratio and serotonin transporter polymorphisms. . Psychol Med. 2005;35:511–517. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selvi Y, Gulec M, Agargun MY, Besiroglu L. Mood changes after sleep deprivation in mornlngness-evenlngness chronotypes in healthy individuals. . J Sleep Res. 2007;16:241–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avery D, Wildschiodtz G, Rafaelsen O. REM latency and temperature in affective disorder before and after treatment. . Biol Psychiatry. 1982;17:463–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Souêtre E, Salvati E, Wehr TA, Sack DA, Krebs B, Darcourt G. Twentyfour-hour profiles of body temperature and plasma TSH in bipolar patients during depression and during remission and in normal control subjects. . Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1133–1137. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Cauter E, Leproult R, Kupfer DJ. Effects of gender and age on the levels and circadian rhythmicity of plasma Cortisol. . J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2468–2473. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.7.8675562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salomon RM, Ripley B, Kennedy JS, et al. Diurnal variation of cerebrospinal fluid hypocretin-1 (Orexin-A) levels in control and depressed subjects. . Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:96–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alesci S, Martinez PE, Kelkar S, et al. Major depression is associated with significant diurnal elevations in plasma interleukin-6 levels, a shift of its circadian rhythm, and loss of physiological complexity in its secretion: clinical implications. . J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2522–2530. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Germain A, Nofzinger EA, Meltzer CC, et al. Diurnal variation in regional brain glucose metabolism in depression. . Biol Psychiatry. 2007; 62:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbini B, Benedetti F, Colombo C, Guglielmo E, Campori E, Smeraldi E. Perceived mood and skin body temperature rhythm in depression. . Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;248:157–160. doi: 10.1007/s004060050033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]