Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with a high rate of developing serious medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, dementia, osteoporosis, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. These are conditions that typically occur late in life, and it has been suggested that MDD may be associated with “accelerated aging.” We review several moderators and mediators that may accompany MDD and that may give rise to these comorbid medical conditions. We first review the moderating effects of psychological styles of coping, genetic predisposition, and epigenetic modifications (eg, secondary to childhood adversity). We then focus on several interlinked mediators occurring in MDD (or at least in subtypes of MDD) that may contribute to the medical comorbidity burden and to accelerated aging: limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis alterations, diminution in glucocorticoid receptor function, altered glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, excitotoxicity, increases in intracellular calcium, oxidative stress, a proinflammatory milieu, lowered levels of “counter-regulatory” neurosteroids (such as allopregnanolone and dehydroepiandrosterone), diminished neurotrophic activity, and accelerated cell aging, manifest as alterations in telomerase activity and as shortening of telomeres, which can lead to apoptosis and cell death. In this model, MDD is characterized by a surfeit of potentially destructive mediators and an insufficiency of protective or restorative ones. These factors interact in increasing the likelihood of physical disease and of accelerated aging at the cellular level. We conclude with suggestions for novel mechanism-based therapeutics based on these mediators.

Keywords: depression, cortisol, oxidative stress, inflammation, telomere, child-hood adversity

Abstract

El trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM) tiene una alta frecuencia de asociación con el desarrollo de importantes comorbilidades médicas como enfermedad cardiovascular, accidentes vasculares, demencia, osteoporosis, diabetes y síndrome metabólico. Estas son patologías que de preferencia ocurren en la edad tardía de la vida y se ha propuesto que el TDM puede estar asociado con un “envejecimiento acelerado”. Se revisan algunos moderadores y mediadores que pueden acompañar al TDM y dar origen a estas condiciones médicas comórbidas. En primer lugar se revisan los efectos moderadores de los estilos psicológicos de adaptación, de la predisposición genética y de las modificaciones epigenéticas (por ejemplo, secundarias a la adversidad infantil). A continuación se revisan algunos mediadores interrelacionados que se presentan en el TDM (o al menos en algunos subtipos de TDM) que pueden incidir en la comorbilidad médica y en el envejecimiento acelerado: alteraciones del eje límbicohipotalámico-hipofisiario-adrenal, disminución de la función de los receptores de glucocorticoides, alteraciones en la tolerancia a la glucosa y en la sensibilidad a la insulina, excitotoxicidad, aumento del calcio intracelular, estrés oxidativo, un ambiente proinflamatorio, reducción de los niveles de neuroesteroides “contra-reguladores” (como alopregnanolona y dehidroepiandrosterona), disminución de la actividad neurotrófica y un envejecimiento celular acelerado que se manifiesta en alteraciones de la actividad de la telomerasa y acortamiento de los telómeros, lo que puede llevar a la apoptosis y la muerte celular. En este modelo, el TDM está caracterizado por un exceso de mediadores potencialmente destructores y una insuficiencia de los protectores o restauradores. Estos factores interactúan aumentando la posibilidad de enfermedad física y de un envejecimiento acelerado a nivel celular. Se concluye con propuestas de nuevas terapias basadas en los mecanismos que regulan estos mediadores.

Abstract

Le trouble dépressif majeur (TDM) est associé à un taux élevé de comorbidités graves comme les pathologies card iovasculaires, les accidents vasculaires cérébrauxl (AVC), la démence, l'ostéoporose, le diabète et le syndrome métabolique. Ces pathologies surviennent habituellement tard dans la vie, et c'est pourquoi certains ont suggéré que le TDM pourrait être associé à un « vieillissement accéléré ». Dans cette revue, nous analysons plusieurs modérateurs et médiateurs pouvant accompagner le TDM et susceptibles de précipiter ces comorbidités. Tout d'abord, nous passons en revue les effets modérateurs des stratégies psychologiques d'adaptation (coping), des prédispositions génétiques et des modifications épigénétiques (par ex secondaires à des difficultés dans l'enfance). Nous nous consacrons ensuite à plusieurs médiateurs liés entre eux intervenant dans le TDM (ou au moins dans certains sous-types de TDM) qui pourraient contribuer à la charge comorbide et à l'accélération du vieillissement: modifications de l'axe limbo-hypophyso-hypothalamo-surrénalien, diminution de la fonction du récepteur des glucocorticoïdes, modification de la tolérance au glucose et de la sensibilité à l'insuline, excitotoxicité, augmentation du calcium intracellulaire, stress oxydatif, un milieu proinflammatoire, abaissement des taux des neurostéroïdes « contre-régulateurs » (comme l'alloprégnanolone et la déhydroépiandrostérone), diminution de l'activité neurotrophique et accélération du vieillissement cellulaire, se manifestant par des modifications de l'activité de la télomérase et par un raccourcissement des télomères, pouvant conduire à l'apoptose et à la mort cellulaire. Dans ce modèle, le TDM se caractérise par un excès de médiateurs potentiellement destructeurs et par une insuffisance de médiateurs protecteurs et restaurateurs. Ces facteurs interagissent en augmentant la probabilité de pathologie physique et de vieillissement accéléré à un niveau cellulaire. Nous concluons avec des suggestions concernant de mécanismes nouveaux pour des traitements s'appuyant sur ces médiateurs.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is typically considered a mental illness, yet pathology associated with MDD is evident in cells and organs throughout the body. For example, MDD is associated with an increased risk of developing atherosclerosis, heart disease, hypertension, stroke, cognitive decline, and dementia (including Alzheimer's disease), osteoporosis, immune impairments (eg, “immunosenescence”), obesity, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes,1-4 and individuals who are afflicted both by MDD and one of these diseases have a poorer prognosis than individuals afflicted by either alone.3 This increased risk of serious medical diseases is not fully explained by lifestyle choices such as diet, exercise, and smoking, and the reasons for the heightened risk remain unknown.4 Moreover, many of the medical comorbidities seen in MDD are diseases more commonly seen with advanced age, and MDD has even been characterized as a disease of “accelerated aging.”1,5,6 In this review article, we explore certain biological mediators that are dysregulated in MDD and that may contribute to the depressed state itself, to the comorbid medical conditions, and to “accelerated aging.” Discovering novel pathological mediators in MDD could help identify new targets for treating depression and its comorbid medical conditions and could help reclassify MDD as a multisystem disorder rather than one confined to the brain.

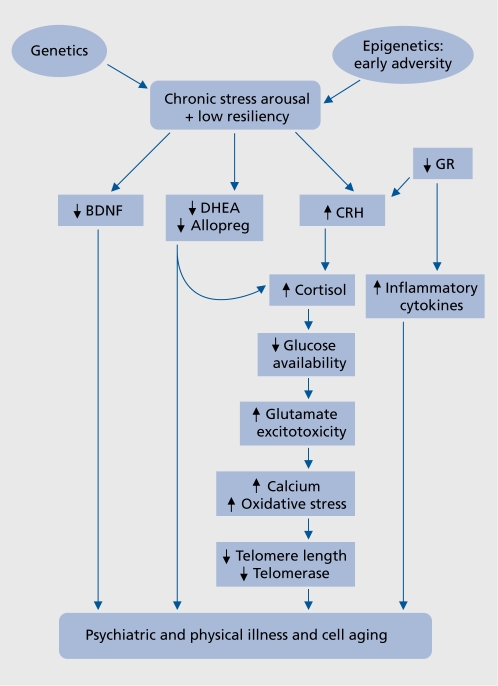

Theoretical model

We propose a model of MDD comprised of certain pathogenic processes that are interlinked and often recursive, that occur in the brain and in the periphery, and that can culminate in cellular damage, cellular aging, and disease.6-10 This model is presented schematically in Figure 1 and is briefly described in this introduction; the individual moderators and mediators are described in greater detail in the remainder of this article. This model is not intended to be complete or all-encompassing but is meant to highlight and connect certain interesting findings in the study of depression. It does not propose that each component is necessary or sufficient, or that the specified mediators are the sole routes to MDD. It also does not speak to the directions of causality between depression and physical pathology. Further, many of the specified mediators may serve either protective or destructive functions depending on their context and chronicity.11-13 Nonetheless, the model presented here provides testable hypotheses for further investigation and provides rationales for considering novel treatment approaches. Earlier reviews of this model have been published elsewhere.5,6,10

Figure 1. Model of multiple pathways leading to psychiatric and physical llness and cell aging. In conjunction with genetic and epigenetic moderators, elevated cortisol levels, associated with downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor (GC) function (GC resistance) may result in altered immune function, leading to excessive synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines. Changes in glucocorticoidmediated activities also result in genomic changes (altered levels of certain neurotransmitters, neurotrophins, and other mediators), as well as dysregulation of the limbic-hypothalamicpituitary adrenal (LHPA) axis that might contribute to neuroendangerment or neurotoxicity, perhaps leading to depressive or cognitive symptoms. Dysregulation of the LPHA axis can also lead to intracellular glucose deficiency, glutamatergic hyperactivity, increased cellular calcium concentrations, mitochondrial damage, free radial generation, and increased oxidative stress. This cascade of events, coupled with a milieu of increased inflammatory cytokines, may lead to accelerated cellular aging via effects on the telomere/telomerase maintenance system. Dysregulation of normal compensatory mechanisms, such as increased neurosteroid or neurotrophin production, may further result in inability to reduce cellular damage, and thereby exacerbate destructive processes. This juxtaposition of enhanced destructive processes with diminished protective/restorative processes may culminate in cellular damage, apoptosis, and physical disease. Allopreg, allopregnanolone; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CRH, corticotropin releasing hormone; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; GR, glucocorticoid receptor.

In brief, psychological and physical stressors trigger physiological responses that are acutely important for successful adaptation to the stress (“stress arousal”). However, when stress responses are disrupted or inappropriately prolonged, endangering effects may supersede the protective ones. The “cost” to the organism of maintaining these physiological responses over prolonged periods has been termed “allostatic load”13 or “arousal pathology,”14 and it has repeatedly been associated with poor medical outcomes.12 In addition to chronicity of the stress response, certain psychological, environmental, genetic, and epigenetic circumstances (discussed below) favor dysregulation of two main stress response effectors, the limbic-hypothalamic -pituitaryadrenal (LHPA) axis and the locus coeruleus noradrenergic (NE) system.15 A particular problem may arise when these two systems, which are generally counterregulatory, activate one another for prolonged periods of time (as may be seen in melancholic depression).15 The failure of glucocorticoids (GCs) to effectively counter-regulate stress-induced NE and LHPA activity may underlie critical aspects of MDD.15 Prolonged LHPA axis dysregulation can lead to neuroendangering or neurotoxic effects in vulnerable brain regions (eg, prefrontal cortex and hippocampus).16 It can also lead to energetic disturbances (decreased intracellular glucose availability and insulin resistance), glutamatergic hyperactivity/excitotoxicity, increased intracellular calcium concentrations, mitochondrial damage, free radical generation and oxidative stress, immune alterations (leading to a proinflammatory milieu), and accelerated cell aging (via effects on the telomere/telomerase maintenance system). The nature of cortisol abnormalities in MDD is complex, however, and will be discussed below. Prolonged activation of central NE systems, as often seen in melancholic depression, may be associated with worsened outcome in cardiovascular diseases and with accelerated cell aging at the level of the telomere.9,15

In addition to increases in these destructive processes, normal compensatory or reparative processes may be diminished, eg, diminution of counter-regulatory neurosteroids, eg, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA),17 and allopregnanolone,18 decreased antioxidant compounds, diminished anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory cytokines, decreased neurotrophic factor concentrations, eg, brainderived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and altered telomerase activity. This juxtaposition of enhanced destructive processes with diminished (or inadequate) protective or restorative ones can culminate in cellular damage and physical disease (Table I). This model will be explored in greater depth in the following sections.

Table I. Possibly damaging and protective mediators in major depression LHPA, limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor. * Evidence is mixed as to whether DHEA concentrations are elevated or lowered in depression. ** Evidence is mixed as to whether the anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory cytokine, IL10, is elevated or lowered in depression. *** Evidence is mixed as to whether telomerase activity is elevated or lowered in states of chronic stress and depression.

| Potentially damaging mediators | Potentially protective mediators |

| Increased | Decreased |

| • Hyperactive LHPA axis and hypercortisolemia (with net hypercortisolism or hypocortisolism) | • Neurosteroids (eg, DHEA* and allopregnanolone) |

| • Insulin sensitivity | |

| • Intracellular glucose | |

| • Synaptic glutamate and excitotoxicity | • Antioxidants |

| • Anti-inflammatory/immuno-modulatory cytokines** | |

| • Intracytoplasmic calcium | |

| • Free radicals with oxidative stress | • Neurotrophic factors (eg, BDNF) |

| • Inflammatory cytokines | • Telomerase*** |

Moderators

Psychological stress and individual differences

Psychological stress is frequently a precipitant of depressive episodes,19 and under certain circumstances it can initiate the biochemical cascade described here.7,8,10,13,16,20 It is apparent, though, that individuals respond very differently to stress, due, in part, to differences in coping strategies, disposition, temperament, and cognitive attributional styles.21-23 These can moderate stress-associated biological changes such as LHPA axis arousal,23 inflammation,22,24 neurogenesis,25 amygdala arousal,26 and cell aging. In the first study examining a personality trait and telomere length, O'Donovan et al found that pessimism was related to shorter telomere length, as well as higher IL-6 concentrations.22 In a study of the effects of early-life parental loss on later-life depression, the quality of the family and home's adaptation to the loss was the single most power-ful predictor of adult psychopathology, and was more important than the loss itself.27 Biochemical aspects of resilience vs stress vulnerability will not be covered here but have recently been reviewed.28

Adverse childhood events

Alexander Pope noted in 1734, that “as the twig is bent, the tree is inclined.” A rapidly expanding body of evidence suggests that early-life adversity (such as parental loss, neglect, and abuse) predisposes to adult depression27,29 as well as to LHPA axis hyper-reactivity to stress,27,30 increased allostatic load,13,31 diminished hippocampal volume (although this is controversial),32 lower brain serotonin transporter binding potential,33 and a myriad of adult physical diseases.34 Childhood adversity also predisposes to alterations in many of the mediators presented in our model of stress/depression/illness/cell aging, such as: inflammation,35,36 oxidative stress,37 neurotrophic factors,38 neurosteroids,39 glucose/insulin/ insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) regulation,40 telomerase activity,41 and telomere length.36,42-44 Alterations in LHPA axis activity (increased or decreased) have been well described in victims of childhood adversity, even when the individuals are not currently depressed.27,30 In fact, several instances of neurobiological changes reported in MDD may be more attributable to histories of early-life adversity,30,32 which are over-represented among individuals with MDD, than to the MDD itself. Thus, early-life adversity seems capable of “reprogramming” the individual to a certain lifetime repertoire of altered physiological responses to stress and to vulnerability to psychiatric and physical illness. This reprogramming toward stress arousal and preparedness may be adaptive when the individual is likely to be confronted with a lifetime of continuous adversity, but is clearly disadvantageous otherwise. The causes of early adversity-induced behavioral and biochemical changes, and the explanation for the very long-lasting effects of such adversity, are the subject of intense investigation. One explanation that has attracted much attention is epigenetic changes,45,46 discussed in the next section.

Genetic and epigenetic moderators

A number of variants in candidate genes have been implicated in contributing to maladaptive and resilient responses that underlie alterations in neuronal plasticity and subsequent behavioral depression.47 Evidence is strongest for genes involved in HPA regulation and stress (corticotrophin-releasing hormone [CRH]1; glucocorticoid receptor [GR]), regulatory neurotransmitters, transporters, and receptors (serotonin (5-HT)1A, 5HT2, 5-HTTLPR, NET), neurotrophic factors, (brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF], nuclear factor-kappaB, mitogen-activated protein kinase-1) and transcription factors (cAMP response element binding, Re-1 silencing transcription factor, delta FosB), but variations in other secondary modulatory factors (g-aminobutyric acid [GABA], catechol-O-methyl transferase, monoamine oxidase, dynorphin, neuropeptide-Y) have also been hypothesized to be important in determining individual differences in stress response.48 Studies of the CRH-1 gene in humans, for example, have shown that specific variants are associated with differential hormonal responses to stress, and with differing rates of depression and suicidal behavior.49 Increasingly, such genetic effects have themselves been found to be modulated by individual variation in environmental context and history (gene x environment, GxE).45 Epigenetics, which focuses on nongenomic alterations of gene expression, provides a mechanism for understanding such findings, through alteration of DNA methylation and subsequent silencing of gene expression or through physical changes in DNA packaging into histones.50 A comprehensive review of this literature is beyond the scope of this article, but the findings of selective recent studies in these areas are illustrative of the regulatory complexity that influences the possible translation of stressful experiences into depression. Long-lasting epigenetic effects of early life experience on hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal (HPA) responses have been demonstrated most clearly in animal models of differential maternal behavior and social isolation.45,46 Augmented maternal care was associated with reduced hypothalamic response to stress in rat pups and altered expression of CRH into adulthood.51 Suggestive human data compatible with these mechanisms have been reported.28,52 Oberlander et al,53 for example, found that prenatal exposure to third trimester maternal depression was associated with increased methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene at 3 months of age in the newborn child, while McGowan45 reported decreased levels of GR expression in the hippocampus of suicide victims with a history of childhood abuse, in comparison with those without such history and to controls. Tyrka and colleagues54 have also shown that variants in the CRH1 receptor gene appear to interact with a history of childhood abuse in determining cortical response to CRH. A separate body of research has focused on genetic investigations in components of serotonergic function, most commonly on a variant in the serotonin promoter (5HTTLPR), and, to a lesser extent, on serotonin receptor genes.55 In a small-scale study that remains controversial, Caspi et al56 reported that the effect of a variant in 5HTTLPR on increasing risk of depression was dependent upon a history of previous life stresses; several large-scale attempts at replication failed to support these conclusions and subsequent meta-analyses have been both positive and negative.57,58 Ressler et al59 have suggested that gene x gene x environment interactions may be involved, and reported that 5-HTTLPR alleles interacted with CRH1 haplotypes and child abuse history in predicting depressive symptoms. Others, however, have found it hard to demonstrate such effects.55 Yet another example of a potential GxGxE interaction was found in a study by Kauffman et al60 of child abuse victims, in whom BDNF and 5-HTTLPR genotypes interacted with maltreatment history in predicting depression, with social support showing some moderating influence. Despite the persuasive empirical animal data, the clinical relevance of epigenetic effects of stress on human emotional behavior is yet to be convincingly established.

Biochemical mediators

Glucocorticoids

Elevated circulating GC levels are often observed in depressed individuals (especially in those with severe, melancholic, psychotic, or inpatient depressions), although considerable variability exists between studies, between individuals, and even within individuals over time, and some individuals are even hypocortisolemic.61,62 The physiological significance of increased circulating GC levels remains unknown, and it is debatable whether hypercortisolemia results in hypercortisolism at the cellular level, or, rather, in hypocortisolism, perhaps due to downregulation of the GR (often referred to as “GC resistance”).20 Thus, determination of “net” GC activity in depressed individuals at the intracellular level has remained elusive.63,64 In fact, different subclasses of depressed individuals may show opposite patterns of limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (LHPA) axis activity,15 and levels of LHPA activation may be more related to individual depressive symptoms than to the depressive syndrome per se.65 Further, it is possible that both hypo- and hypercortisolism are related to depression, in an inverted-U shaped manner.62 Complicating our understanding of this issue, novel treatment strategies that decrease or increase GC activity may show antidepressant effects in certain patients.66-69 The “hypocortisolism” hypothesis is supported by findings that proinflammatory cytokine levels (eg, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-a, interleukin [IL]-1ß and IL-6) tend to be increased in the serum of depressed patients, and that proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to depressive symptomatology. Since cortisol typically has anti-inflammatory actions and suppresses proinflammatory cytokines (although there are instances to the contrary [eg, ref 70]), the coexistence of elevated cortisol and elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels suggests an insensitivity to cortisol at the level of the lymphocyte GR.20 Further supporting this notion, inflammatory cytokines downregulate GRs.20 Also, antidepressants typically increase GR binding activity,20 although in so doing, negative feedback onto the HPA axis is increased.71 On the other hand, the “hypercortisolism” hypothesis is supported by certain phenotypic somatic features suggestive of cortisol excess and end-organ cortisol receptor overactivation in some individuals with depression, eg, osteoporosis, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, a relative hypokalemic alkalosis accompanied by neutrophilia and lymphocytosis, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and visceral/intra-abdominal adiposity.72,73 Further support of net GC overactivation is provided by evidence of altered expression of target genes such as BDNF, which are believed to be under negative regulatory control by cortisol.74

Pathologically elevated or diminished GC activity might have adverse neurobehavioral and physical health sequellae.72,75 Chronic hypercortisolemia, in particular, has been proposed by Sapolsky and others16 to result in a biochemical “cascade,” which can culminate in cell endangerment or cell death in certain cells, including cells in the hippocampus. In the simplest description of this model, GC excess engenders a state of intracellular glucoprivation (insufficient intracellular glucose energy stores) in certain cells, impairing the ability of glia and other cells to clear synaptic glutamate. The resulting excitotoxicity results in excessive influx and release of calcium into the cytoplasm, which contributes to oxidative damage, proteolysis, and cytoskeletal damage. Unchecked, these processes can culminate in diminished cell viability or cell death.

Neurosteroids

Although cortisol concentrations are often reported as elevated in depression, CSF concentrations of the potent GABA-A receptor agonist neurosteroid, allopregnanolone, are decreased in unmedicated depressives, and CSF levels of allopregnanolone increase with treatment in direct proportion to the antidepressant effect.76 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants rapidly increase allopregnanolone synthesis, and this may contribute to their anxiolytic effects.77,78 Another neurosteroid, DHEA, which may have “anticortisol” effects, has been reported to be both high and low in depression.17 Notably, both of these neurosteroids modulate HPA axis activity17,18 and immune system activity,17,79 antagonize oxidative stress17,80 and have certain neuroprotective effects.17,81 Depressed patients entering remission show decreases in plasma cortisol concentrations along with increases in plasma allopregnanolone concentrations.82 Endogenous decreases in this neurosteroid concentrations or exogenously produced increases in their concentrations might be expected to have damaging or beneficial effects, respectively, in the context of depression,17,78,83,84 and treatment trials have demonstrated significant antidepressant effects of exogenously administered DHEA.17 Animal models suggest that 3 a hydroxy-5 a reduced steroids (allopregnanolone and allotetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone) are responsive to stress85 and may function to restore normal g-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic and hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal function following stress.18,85 In vitro, allopregnanolone suppresses release of gonadotropinreleasing hormone86 or CRH87 via a GABA-A mediated mechanism. Allopregnanolone or allotetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone can also attenuate stress-induced increases in plasma ACTH and corticosterone and can affect arginine vasopression transcription in the hypothalamus (paraventricular nucleus).18 Under chronic stress or in psychiatric disorders, dysregulation of the HPA axis could be exacerbated if there is insufficient activity of these “counter-regulatory” neurosteroids. In addition to protection against acute or chronic stress, neurosteroids such as allopregnanolone and allotetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone may be neuroprotective against early life stressors88 or against deleterious effects of social isolation.89 In this way, these neurosteroids may be neuroprotective during development and may affect future responsiveness to stress.

The detrimental effects of neurosteroid dysregulation on stress responses has been particularly documented in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).90,91 PMDD is a depressive disorder that is characterized by cyclic recurrence, during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, of a variety of physical and emotional symptoms that are so severe as to interfere with daily activities. In these studies in women with PMDD, both high and low concentrations of allopregnanolone during the luteal phase of the menstrual have been reported. However, women with PMDD have reduced responsiveness to neurosteroids (on GABA-A receptors)92 as well as a blunted stress response (failing to demonstrate an increase in allopregnanolone concentrations after acute stress) in women with PMDD and a prior history of depression.90 Furthermore, women with PMDD who also had prior histories of depression showed significant decreases in allopregnanolone after acute stress.90 These data highlight that long-term histories of depression may be associated with persistent, long-term effects on the responsivity of the neurosteroid system, as well as long-term effects on modulation of the HPA axis following stress.

Glucose and insulin regulation

Abnormalities of glucose homeostasis (eg, insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance) are seen in MDD, even in individuals who are nonobese and not diabetic.93 These glucose and insulin abnormalities are most pronounced in hypercortisolemic depressed individuals,94 as would be predicted based on cortisol's well-known antiinsulin effects. Hypercortisolemic depressives, compared with normocortisolemic ones, are also at increased risk of having increased abdominal (visceral) fat deposition95 and the metabolic syndrome,96 which are also risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Insulin resistance and diminished cellular glucose uptake can also lead to a dangerous “energetic crisis.”7,16 When this occurs in the hippocampus,16 for example, hippocampal excitotoxicity may develop, since there is insufficient energy available to clear glutamate from the synapse. Thereafter, cytosolic calcium is mobilized, triggering oxygen free radical formation and cytoskeletal proteolysis. The relevance of this in humans was demonstrated in a PET scan study, in which cortisol administration to normal individuals resulted in significant reductions in hippocampal glucose utilization.97 The importance of hippocampal insulin resistance for depression and cognitive disorders (eg, Alzheimer's disease) is the subject of active investigation.98,99

Over and above these direct effects on energy balance, prolonged exposure to glucose intolerance and insulin resistance is associated with accelerated biological aging7,100 including shortened telomere length,101 and visceral adiposity is associated with increased inflammation and oxidation,102,103 both of which, themselves, promote accelerated biological aging.7 These will be further discussed below in the sections on inflammation, oxidation, and cell aging.

Immune function

Dysregulation of the LHPA axis contributes to immune dysregulation in depression, and immune dysregulation, in turn, can activate the HPA axis and precipitate depressive symptoms.20 Immune dysregulation may be an important pathway by which depression heightens the risk of serious medical comorbidity.7,104,105 Several major proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1ß, IL-2, IL-6 and TNF-a, are elevated in depression, either basally or in response to mitogen stimulation or acute stress.20,106,107 Conversely, certain anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory cytokines, such as IL-1 receptor antagonist and IL10 may be decreased or dysregulated.106 Indeed, the ratio of proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory/ immunomodulatory cytokines may be disturbed in depression and could result in net increased inflammatory activity106 as well as in oxidative stress.108 Converging findings suggest that high peripheral levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, are associated with the activation of central inflammatory mechanisms that can adversely affect the hippocampus, where IL-6 receptors are abundantly expressed.109 High proinflammatory cytokine levels, for example, may directly contribute to depression, decreased neurotrophic support, and altered glutamate release/reuptake and hippocampal neurodegeneration,110 and, plasma IL-6 levels are inversely correlated with hippocampal gray matter in healthy humans.111 Further, inappropriately and chronically elevated proinflammatory cytokines can contribute to accelerated biological aging (eg, premature shortening of immune cell telomeres112). Interestingly, the development of immunosenescence (eg, the loss of the CD28 marker from CD8+ T cells), can further aggravate the proinflammatory milieu, since CD8+CD28- cells hypersecrete IL-6.113 It should be noted, however, that due to the complexity of cytokine actions in neurons and glia, the end effect of individual cytokines may be either detrimental or protective, depending on the circumstances.106

Oxidation

Stress and increased LHPA axis activity can also increase oxidative stress and decrease antioxidant defenses.5 ,7,114 Oxidative stress often increases with aging and various disease states, while antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities decrease, resulting in a heightened likelihood of cellular damage and of a senescent phenotype.7,115 The co-occurrence of oxidative stress and inflammation (the so-called “evil twins” of brain aging115), as may be seen in depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), stroke, Alzheimer's disease, and others, can be especially detrimental. Oxidative stress occurs when the production of oxygen free radicals (and other oxidized molecules) exceeds the capacity of the body's antioxidants to neutralize them. Oxidative stress damages DNA, protein, lipids, and other macromolecules in many tissues, with telomeres (discussed below) and the brain being particularly sensitive. Elevated plasma and/or urine oxidative stress markers (eg, increased F2-isoprostanes and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine [8-OHdG], along with decreased antioxidant compounds, such as Vitamin C, Vitamin E, and Coenzyme Q) have been reported in individuals with depression and in those with chronic psychological stress, and the concentration of peripheral oxidative stress markers is positively correlated with the severity and chronicity of depression.114,116 Further, the ratio of serum oxidized lipids (F2-isoprostanes) to antioxidants (Vitamin E) is directly related to psychological stress.8 Importantly, this ratio (and the ratio of F2-isoprostanes to another antioxidant, Vitamin C) is inversely related to telomere length in chronically stressed caregivers8 and in individuals with major depression.117 Oxidative stress markers are also correlated with decreased telomerase activity.118 Further, diminished levels of antioxidants reportedly lower BDNF activity.119 Interestingly, antidepressants decrease oxidative stress.120 Since cellular oxidative damage may be an important component of the aging process, prolonged or repeated exposure to oxidative stress might accelerate aspects of biological aging and promote the development of aging-related diseases in depressed individuals.114 It is unknown whether antioxidant treatment would retard stress- or depressionrelated aging; this is discussed below under “novel treatment implications.”

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

The “neurotrophic model” of depression74 emphasizes the centrality of neurogenesis and neuronal plasticity in the pathophysiology of depression. It posits that diminished hippocampal BDNF activity, caused by stress or excessive GCs, impairs the ability of stem cells in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (as well as cells in the subventricular zone, projecting to the prefrontal cortex) to remain viable and to proliferate into mature cells. It is not known whether such effects can cause depression, but they may be relevant to the mechanism of action of antidepressant treatments.121 Unmedicated patients with depression have decreased hippocampal (at autopsy) and serum concentrations of BDNF121,122 Over 20 studies have documented decreased serum concentrations of BDNF in unmedicated depressed individuals; this is now one of the most consistently replicated biochemical findings in major depression.121,123 Further, serum BDNF concentrations increase with antidepressant treatment.121,123 The relationship of peripheral BDNF concentrations to central ones is not known, but even peripherally administered BDNF abrogates depressive and anxiety-like behaviors and increases hippocampal neurogenesis in mice, suggesting that serum BDNF concentrations are functionally significant for brain function and are more than merely a biomarker.124 A role of BDNF in antidepressant mechanisms of action is supported by findings that hippocampal neurogenesis (in animals) and serum BDNF concentrations (in depressed humans) increase with antidepressant treatment,121,123 and that hippocampal neurogenesis and intact BDNF expression are required for behavioral effects of antidepressants in animals.125,126

Apart from its direct neurotrophic actions, BDNF also has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects that may contribute to its neuroprotective efficacy,127 and BDNF, in concert with telomerase (discussed below) promotes the growth of developing neurons.128 In addition, BDNF (despite its name) has significant peripheral actions that are important for physical health, and the low levels of BDNF seen in MDD may be involved in certain comorbid illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.129 For example, BDNF improves glucose and lipid profiles, enhances glucose utilization, suppresses food intake, has an insulinotropic effect and protects cells in the islets of Langerhans (reviewed in ref 129). Plasma levels of BDNF are low in type 2 diabetes and are inversely correlated with fasting glucose levels.129 Indeed, BDNF is increasingly considered not only a neurotrophin but a metabotrophin,129 and its dysregulation has been proposed as a unifying feature of several clustered conditions, such as MDD, Alzheimer's disease, and diabetes.130

Cell aging: telomeres and telomerase

Telomeres are DNA-protein complexes that cap the ends of linear DNA strands, protecting DNA from damage.131 When telomeres reach a critically short length, as may happen when cells undergo repeated mitotic divisions in the absence of adequate telomerase (eg, immune cells and stem cells, including neurogenic stem cells in the hippocampus), cells become susceptible to apoptosis and death. Even in nondividing cells, such as mature neurons, telomeres can become shortened by oxidative stress, which preferentially damages telomeres to a greater extent than nontelomeric DNA. This nonmitotic type of telomere shortening also increases susceptibly to apoptosis and cell death. Telomere length is a robust indicator of “biological age” (as opposed to just chronological age) and may represent a cumulative log of the number of cell divisions and a cumulative record of exposure to genotoxic and cytotoxic processes such as oxidation.7-9,113,131,132 Telomere length may also represent a biomarker for assessing an individual's cumulative exposure to, or ability to cope with, depression or stressful conditions. For example, chronically stressed8,9 or depressed133-135 individuals show premature leukocyte telomere shortening, a sign of cellular aging. In the former study, telomere length was inversely correlated with perceived stress and with cumulative duration of caregiving stress.8 The estimated magnitude of the acceleration of biological aging in these studies was not trivial; it was estimated as approximately 9 to 17 additional years of chronological aging in the stressed caregivers and approximately 6 to 10 years in the depressed individuals. Preliminary data from our group suggest that telomere loss in MDD is most apparent in those individuals with more chronic courses of depression,117 but another study did not observe that.135 Interestingly, individuals with histories of early-life adversity or abuse also have shortened leukocyte telomeres.36,42,43 Since individuals with MDD are more likely to have experienced earlylife adversity, it remains to be determined how much of the telomere shortening seen in studies of MDD relate to the MDD per se vs the histories of early-life adversity. In individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), telomere shortening was more closely linked to adverse childhood events than to the PTSD per se.44

The importance of accelerated telomere shortening for understanding comorbid medical illnesses and premature mortality in depressed individuals is highlighted by multiple studies in nondepressed populations showing significantly increased medical morbidity and earlier mortality in those with shortened telomeres.7,136 For example, shortened leukocyte telomeres are associated with a greater than 3-fold increase in the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke and with a greater than 8-fold increase in the risk of death from infectious disease.137 Thus, cell aging (as manifest by shortened telomeres), may provide a conceptual link between depression and its associated medical comorbidities and shortened life span.7,104,132 The causes of accelerated telomere loss in MDD are not known, but they may include chronic exposure to inflammation and oxidation, both of which are commonly seen in MDD and both of which are associated with telomere shortening. In our own studies, telomere length in MDD was inversely correlated with inflammation (IL-6 concentrations) and oxidative stress (the F2-isoprostane/ Vitamin C ratio).117

Telomere length is determined by the balance between telomere shortening stimuli (eg, mitotic divisions and exposure to inflammation and oxidation) and telomere lengthening or reparative stimuli. A major enzyme responsible for protecting, repairing, and lengthening telomeres is telomerase, a ribonucleoproptein enzyme that elongates telomeres, thereby counteracting telomere shortening and maintaining cellular viability.131 Telomerase may also have antiaging or cell survival-promoting effects independent of its effects on telomere length by regulating transcription of growth factors, synergizing with the neurotrophic effects of BDNF, having antioxidant effects and intrinsic antiapoptotic effects, protecting cells from necrosis, and stimulating cell growth in adverse conditions (eg, ref 128). In one study in which telomere shortening was observed, telomerase activity

was significantly diminished in stressed (generally nondepressed) caregivers8 but, in another caregiver study (in which caregivers were more depressed than controls), telomerase activity was significantly increased.138 We recently found that telomerase activity was significantly increased in unmedicated depressed individuals.139 It is possible that increased telomerase activity, in the face of shortened telomeres, is an attempted compensatory response to telomere shortening.138,139

Pointing to the inter-relatedness of several of the mediators considered in this review, telomerase activity can be down-regulated by cortisol,140 tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-a and certain growth factors, and upregulated by IL-6 and certain other inflammatory cytokines, insulinlike growth factor-1, fibroblast growth factor-2, vascular endothelial growth factor, estrogen, and others.141

Novel treatment implications

To the extent the biochemical mediators we have described are pathophysiologically involved in MDD and its medical comorbidities, new classes of treatments should be considered, and certain noncanonical mechanisms of action of traditional antidepressants should be emphasized in new drug development. Some of these novel approaches are already under investigation, while others remain to be tested. In Table II, we list certain traditional and nontraditional, but mechanism-based, interventions that may ameliorate the biochemical mediators we have discussed. These interventions range from purely behavioral (eg, exercise and improved fitness, environmental enrichment, yoga and meditation, dietary macronutrient modifications and calorie restriction) (see refs 7,142-144 for description of these behavioral approaches) to more purely medication-based (see ref 145 for additional descriptions of novel biological mechanism-based therapeutics). For example, early work suggests the promise, at least in certain patients, of antiglucocorticoids,67-69 DHEA supplementation,17 insulin receptor sensitizers,99,146 glutamate antagonists,147 calcium blockers,148 anti-inflammatories,149 antioxidants,150 increased BDNF delivery to the brain, 124,151 and, most speculatively, telomerase enhancers.152,153

Table II. Potential mechanism-based therapeutic interventions. LHPA, limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; GC, glucocorticoid; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; CRH, corticotrophin-releasing hormone; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor .

| Biochemical mediator | Potential treatment interventions |

| Stress vulnerability | Stress reduction; meditation; lifestyle changes7,142,154 |

| Epigenetic changes | Epigenetic reprogramming155,156 |

| LHPA axis dysregulation | Antidepressants upregulate GR function71 |

| (Hypercortisolemia + GC resistance) | CRH antagonists157 |

| Cortisol antagonists and GR antagonists or agonists66,69 | |

| Glucose/insulin dysregulation | Insulin receptor sensitizers99,146 |

| Glutamate/excitotoxicity | Glutamate antagonists147 |

| Oxidative stress | Antidepressants have antioxidant effects120 |

| Antioxidants150,158 | |

| Intracellular calcium | Calcium blockers148 |

| Inflammation | Antidepressants have anti-inflammatory effects20 |

| Anti-inflammatory drugs, TNF-a antagonists, etc149 | |

| Decreased counter-regulatory neurosteroids | SSRIs increase allopregnanolone synthesis77,78 |

| DHEA administration17 | |

| Decreased BDNF | Antidepressants (esp SSRIs) increase BDNF concentrations122,123 |

| Environmental enrichment143,144 | |

| Exercise143 | |

| Dietary restriction143 | |

| BDNF administration via novel routes or vectors124,151 | |

| Cell aging (telomeres; telomerase) | Telomerase activation152,153 |

Summary: is depression accompanied by accelerated aging?

We began this review article by noting that depressed individuals are at increased risk of developing physical illnesses more commonly seen with aging. It remains unknown whether MDD and these medical conditions are causally related. This determination will be important in considering whether primary treatment of the depression (eg, with antidepressant medications or psychotherapy) should additionally treat some of the medical comorbidities (and vice versa) or whether the biochemical mediators that are common to both conditions (eg, inflammation and oxidation) should be a primary treatment focus. We also discussed the potent influence that early-life adversity can have on the subsequent development of depression and medical comorbidities. We noted that many of the biochemical mediators are linked to others, and that there are many examples of bidirectional influence. Finally, we postulated that certain of these mediators have the potential to accelerate cellular aging at the level of DNA. In any event, is important to recognize that MDD may be biologically heterogeneous, and this model may apply only to certain subsets of patients with MDD. This reconceptualization of MDD as a constellation of biochemical features conducive to physical as well as mental distress places MDD firmly in the taxonomy of physical disease and points to new types of treatment.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable intellectual input into this manuscript by Dr Elissa S. Epel, who coauthored previous reviews of an earlier model. We also thank her and Drs Elizabeth H. Blackburn, Jue Lin, Firdaus S. Dhabhar, Yali Su, Steve Hamilton, and J. Craig Nelson for their valued collaboration on our studies of cell aging in depression. This study was funded by an NIMH R01 grant (R01 MH083784), a grant from the O'Shaughnessy Foundation and grants from the UCSF Academic Senate and the UCSF Research Evaluation and Allocation Committee (REAC). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. None of the granting or funding agencies had a role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Selected abbreviations and acronyms

- 5-HT

serotonin

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CRH

corticotrophin-releasing hormone

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- GC

glucocorticoid

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- IL

interleukin

- LHPA

limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- PMDD

premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Portions of this paper are based on a prior review article: Wolkowitz O, Epel ES, Reus VI, Mellon S. Depression gets old fast: do stress and depression accelerate cell aging? Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:327-338.

Financial disclosures: Drs Owen Wolkowitz and Synthia Mellon, along with Drs Elizabeth Blackburn, Elissa Epel, and Jue Lin, on behalf of the Regents of the University of California (who will be assignees of the patent), have applied for a patent covering the use of cell aging markers (including telomerase activity) as a biomarker of depression.

Contributor Information

Owen M. Wolkowitz, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

Victor I. Reus, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

Synthia H. Mellon, Department of OB-GYN and Reproductive Sciences, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heuser I. Depression, endocrinologically a syndrome of premature aging? Maturitas. 2002;41(suppl 1):S19–S23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(02)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntyre RS., Soczynska JK., Konarski JZ., et al. Should depressive syndromes be reclassified as "metabolic syndrome type II"? Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19:257–264. doi: 10.1080/10401230701653377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans DL., Charney DS., Lewis L., et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz R., Beach SR., Ives DG., Martire LM., Ariyo AA., Kop WJ. Association between depression and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1761–1768. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolkowitz OM., Epel ES., Mellon S. When blue turns to grey: do stress and depression accelerate cell aging? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9:2–5. doi: 10.1080/15622970701875601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolkowitz OM., Epel ES., Reus VI., Mellon SH. Depression gets old fast: do stress and depression accelerate cell aging? Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:327–338. doi: 10.1002/da.20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epel ES. Psychological and metabolic stress: a recipe for accelerated cellular aging? Hormones (Athens). 2009;8:7–22. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epel ES., Blackburn EH., Lin J., et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epel ES., Lin J., Wilhelm FH., et al. Cell aging in relation to stress arousal and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolkowitz OM., Epel ES., Reus VI. Stress hormone-related psychopathology: pathophysiological and treatment implications. World J Biol Psychiat. 2001;2:115–143. doi: 10.3109/15622970109026799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selye H. The Stress of Life. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. 1956 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeman T., McEwen BS., Rowe J., Singer B. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;9:4770–4775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081072698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McEwen B. Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:108–124. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulkin J., McEwen BS., Gold PW. Allostasis, amygdala, and anticipatory angst. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1994;18:385–396. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong ML., Kling MA., Munson PJ., et al. Pronounced and sustained central hypernoradrenergic function in major depression with melancholic features: relation to hypercortisolism and corticotropin-releasing hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:325–330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sapolsky RM. The possibility of neurotoxicity in the hippocampus in major depression: a primer on neuron death. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:755–765. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00971-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maninger N., Wolkowitz OM., Reus VI., Epel ES., Mellon SH. Neurobiological and neuropsychiatric effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS). Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:65–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patchev VK., Hassan AH., Holsboer DF., Almeida OF. The neurosteroid tetrahydroprogesterone attenuates the endocrine response to stress and exerts glucocorticoid-like effects on vasopressin gene transcription in the rat hypothalamus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:533–540. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendler K., Karkowski LM., Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raison CL., Miller AH. When not enough is too much: the role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1554–1565. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folkman S., Lazarus RS., Dunkel-Schetter C., DeLongis A., Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Donovan A., Lin J., Dhabhar FS., et al. Pessimism correlates with leukocyte telomere shortness and elevated interleukin-6 in post-menopausal women. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:446–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denson TF., Spanovic M., Miller N. Cognitive appraisals and emotions predict cortisol and immune responses: a meta-analysis of acute laboratory social stressors and emotion inductions. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:823–853. doi: 10.1037/a0016909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stowell JR., Kiecolt-Glaser JK., Glaser R. Perceived stress and cellular immunity: when coping counts. J Behav Med. 2001;24:323–339. doi: 10.1023/a:1010630801589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyons DM., Buckmaster PS., Lee AG., et al. Stress coping stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis in adult monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14823–14827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914568107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor SE., Burklund LJ., Eisenberger NI., et al. Neural bases of moderation of cortisol stress responses by psychosocial resources. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95:197–211. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breier A., Kelsoe JR Jr., Kirwin PD., et al. Early parental loss and development of adult psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:987–993. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350021003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feder A., Nestler EJ., Charney DS. Psychobiology and molecular genetics of resilience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:446–457. doi: 10.1038/nrn2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman DP., Whitfield CL., Felitti VJ., et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heim C., Plotsky PM., Nemeroff CB. Importance of studying the contributions of early adverse experience to neurobiological findings in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:641–648. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grassi-Oliveira R., Ashy M., Stein LM. Psychobiology of childhood maltreatment: effects of allostatic load? Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30:60–68. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462008000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vythilingam M., Heim C., Newport J., et al. Childhood trauma associated with smaller hippocampal volume in women with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:2072–2080. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller JM., Kinnally EL., Ogden RT., et al. Reported childhood abuse is associated with low serotonin transporter binding in vivo in major depressive disorder. Synapse. 2009;63:565–573. doi: 10.1002/syn.20637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anda RF., Felitti VJ., Bremner JD., et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pace TW., Mletzko TC., Alagbe O., et al. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1630–1633. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiecolt-Glaser JK., Gouin JP., Weng NP., et al. Childhood adversity heightens the impact of later-life caregiving stress on telomere length and inflammation. Psychosom Med. 2010;73:16–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820573b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnes SK., Ozanne SE. Pathways linking the early environment to longterm health and lifespan. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. In press. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth TL., Lubin FD., Funk AJ., Sweatt JD. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avital A., Ram E., Maayan R., Weizman A., Richter-Levin G. Effects of early-life stress on behavior and neurosteroid levels in the rat hypothalamus and entorhinal cortex. Brain Res Bull. 2006;68:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas C., Hypponen E., Power C. Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in midadult life: the role of childhood adversity. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1240–e1249. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolkowitz OM., Epel ES., Mellon SH., et al. Major depression and history of childhood sexual abuse are related to increased PBMC telomerase activity. in International Society of Psychoneuroendocrinology Annual Meeting. San Francisco, CA. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kananen L., Surakka I., Pirkola S., et al. Childhood adversities are associated with shorter telomere length at adult age both in individuals with an anxiety disorder and controls. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tyrka AR., Price LH., Kao HT., Porton B., Marsella SA., Carpenter LL. Childhood maltreatment and telomere shortening: preliminary support for an effect of early stress on cellular aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Donovan, A, Epel ES., Lin J., et al. Childhood trauma associated with short leukocyte telomere length in post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. In press. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGowan PO., Sasaki A., DAlessio AC., et al. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weaver IC., Cervoni N., Champagne FA., et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishnan V., Nestler EJ. Linking molecules to mood: new insight into the biology of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1305–1320. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.10030434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeRijk R., de Kloet ER. Corticosteroid receptor genetic polymorphisms and stress responsivity. Endocrine. 2005;28:263–270. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:28:3:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wasserman D., Wasserman J., Sokolowski M. Genetics of HPA-axis, depression and suicidality. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25:278–280. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schroeder M., Krebs MO., Bleich S., Frieling H. Epigenetics and depression: current challenges and new therapeutic options. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:588–592. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833d16c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korosi A., Shanabrough M., McLelland S., et al. Early-life experience reduces excitation to stress-responsive hypothalamic neurons and reprograms the expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone. J Neurosci. 2010;30:703–713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4214-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murgatroyd C., Patchev AV., Wu Y., et al. Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1559–1566. doi: 10.1038/nn.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oberlander TF., Weinberg J., Papsdorf M., Grunau R., Misri S., Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3:97–106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyrka AR., Price LH., Gelernter J., Schepker C., Anderson GM., Carpenter LL. Interaction of childhood maltreatment with the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene: effects on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:681–685. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chipman P., Jorm AF., Tan XY., Easteal S. No association between the serotonin-1A receptor gene single nucleotide polymorphism rs6295C/G and symptoms of anxiety or depression, and no interaction between the polymorphism and environmental stressors of childhood anxiety or recent stressful life events on anxiety or depression. Psychiatr Genet. 2010;20:813. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283351140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caspi A., Sugden K., Moffitt TE., et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karg K., Burmeister M., Shedden K., Sen S. The Serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. In press. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Risch N., Herrell R., Lehner T., et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:2462–2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ressler KJ., Bradley B., Mercer KB., et al. Polymorphisms in CRHR1 and the serotonin transporter loci: gene x gene x environment interactions on depressive symptoms. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:812–824. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaufman J., Yang BZ., Douglas-Palumberi H., et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-5-HTTLPR gene interactions and environmental modifiers of depression in children. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:673–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fries E., Hesse J., Hellhammer J., Hellhammer DH. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bremmer MA., Deek DJ., Beekman AT., Penninx BW., Lips P., Hoogendijk WJ. Major depression in late life is associated with both hypo- and hypercortisolemia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller AH. Letter to the Editor Re: An inflammatory review of glucocorticoids in the CNS. Sorrells SF, Sapolsky RM. Brain Behavior Immun. 2007;21:259–272. 988–989; author reply 990.. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sorrells SF., Sapolsky RM. A pro-inflammatory review of glucocorticoid actions in the CNS. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller KB., Nelson JC. Does the dexamethasone suppression test relate to subtypes, factors, symptoms, or severity? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:769–774. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arana GW., Santos AB., Laraia MT., et al. Dexamethasone for the treatment of depression: a randomized, placebo- controlled, double-blind trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:265–267. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Belanoff J., Schatzberg AF. Glucocorticoid antagonists. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:S56. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolkowitz OM., Reus VI. Treatment of depression with antiglucocorticoid drugs. Psychosomat Med. 1999;61:698–711. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199909000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gallagher P., Watson S., Smith MS., Young AH., Ferrier IN. Antiglucocorticoid treatments for mood disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008CD005168 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005168.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Frank MG., Miguel ZD., Watkins LR., Maier SF. Prior exposure to glucocorticoids sensitizes the neuroinflammatory and peripheral inflammatory responses to E. coli lipopolysaccharide. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barden N., Reul JM., Holsboer F. Do antidepressants stabilize mood through actions on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system? Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:6–11. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93942-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wolkowitz OM., Burke H., Epel ES., Reus VI. Glucocorticoids: mood, memory and mechanisms. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1179:19–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reus VI., Miner C. Evidence for physiological effects of hypercortisolemia in psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res. 1985;14:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(85)90088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Duman RS., Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heim C., Ehlert U., Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uzunova V., Sheline Y., Davis JM., et al. Increase in the cerebrospinal fluid content of neurosteroids in patients with unipolar major depression who are receiving fluoxetine or fluvoxamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3239–3244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Griffin LD., Mellon SH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:13512–13517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guidotti A., Costa E. Can the antidysphoric and anxiolytic profiles of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors be related to their ability to increase brain allopregnanolone availability? Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:865–873. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bauer ME. Chronic stress and immunosenescence: a review. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008;15:241–250. doi: 10.1159/000156467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zampieri S., Mellon SH., Butters TD., et al. Oxidative stress in NPC1 deficient cells: protective effect of allopregnanolone. J Cell Mol Med. 200;13:3786–3796. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang JM., Irwin RW., Liu L., Chen S., Brinton RD. Regeneration in a degenerating brain: potential of allopregnanolone as a neuroregenerative agent. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4:510–517. doi: 10.2174/156720507783018262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Strohle A., Romeo E., Hermann B., et al. Concentrations of 3a-reduced neuroactive steroids and their precursors in plasma of patients with major depression and after clinical recovery. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:274–277. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rupprecht R. Neuroactive steroids: mechanisms of action and neuropsychopharmacological properties. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:139–168. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wolkowitz OM., Reus VI. Neurotransmitters, neurosteroids and neurotrophins: new models of the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2003;4:98–102. doi: 10.1080/15622970310029901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barbaccia ML., Serra M., Purdy RH., Biggio G. Stress and neuroactive steroids. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2001;46:243–272. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(01)46065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Calogero AE., Palumbo MA., Bosboom AM., et al. The neuroactive steroid allopregnanolone suppresses hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone release through a mechanism mediated by the gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor. J Endocrinol. 1998;158:121–125. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1580121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Patchev VK., Shoaib M., Holsboer F., Almeida OF. The neurosteroid tetrahydroprogesterone counteracts corticotropin-releasing hormoneinduced anxiety and alters the release and gene expression of corticotropinreleasing hormone in the rat hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 1994;62:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Patchev VK., Montkowski A., Rouskova D., et al. Neonatal treatment of rats with the neuroactive steroid tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC) abolishes the behavioral and neuroendocrine consequences of adverse early life events. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:962–966. doi: 10.1172/JCI119261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dong E., Matsumoto K., Uzunov G., et al. Brain 5alpha-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone synthesis in a mouse model of protracted social isolation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2849–2854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051628598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Klatzkin RR., Morrow AL., Light KC., Pedersen CA., Girdler SS. Histories of depression, allopregnanolone responses to stress, and premenstrual symptoms in women. Biol Psychol. 2006;71:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rapkin AJ., Morgan M., Goldman L., et al. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:709–714. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sundström I., Andersson A., Nyberg S., et al. Patients with premenstrual syndrome have a different sensitivity to a neuroactive steroid during the menstrual cycle compared to control subjects. Neuroendocrinology. 1998;67:126–138. doi: 10.1159/000054307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hennings JM., Ising M., Grautoff S., et al. Glucose tolerance in depressed inpatients, under treatment with mirtazapine and in healthy controls. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:98–100. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kopf D., Westphal S., Luley CW., et al. Lipid metabolism and insulin resistance in depressed patients: significance of weight, hypercortisolism, and antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:527–531. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000138762.23482.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weber-Hamann B., Hentschel F., Kniest A., et al. Hypercortisolemic depression is associated with increased intra-abdominal fat. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:274–277. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vogelzangs N., Suthers K., Ferrucci L., et al. Hypercortisolemic depression is associated with the metabolic syndrome in late-life. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.de Leon MJ., McRae T., Rusinek H., et al. Cortisol reduces hippocampal glucose metabolism in normal elderly, but not in Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3251–3259. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.10.4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McIntyre RS., Soczynska JZ., Lewis GF., et al. Managing psychiatric disorders with antidiabetic agents: translational research and treatment opportunities. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:1305–1321. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.10.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rasgon NL., Kenna HA. Insulin resistance in depressive disorders and Alzheimer's disease: revisiting the missing link hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26 Suppl 1:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Avogaro A., de Kreutzenberg SV., Fadini GP. Insulin signaling and life span. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:301–314. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gardner JP., Srinivasan SR., Chen W., et al. Rise in insulin resistance is associated with escalated telomere attrition. Circulation. 2005;111:2171–2177. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163550.70487.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alvehus M., Buren J., Sjostrom M., Goedecke J., Olsson T. The human visceral fat depot has a unique inflammatory profile. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18:879–883. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Palmieri VO., Grattagliano I., Portincasa P., Palasciano G. Systemic oxidative alterations are associated with visceral adiposity and liver steatosis in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Nutr. 2006;136:3022–3026. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.12.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bauer ME., Jeckel CM., Luz C. The role of stress factors during aging of the immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:139–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kiecolt-Glaser J.K., Glaser R. Depression and immune function: central pathways to morbidity and mortality. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:873–876. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dhabhar FS., Burke HM., Epel ES., et al. Low serum IL-10 concentrations and loss of regulatory association between IL-6 and IL-10 in adults with major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:962–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dowlati Y., Hermann N., Swardfager W., et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kaur K., Sharma AK., Dhingra S., Singal PK. Interplay of TNF-alpha and IL-10 in regulating oxidative stress in isolated adult cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pickering M., O'Connor J.J. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and their effects in the dentate gyrus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:339–354. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Miller AH., Maletic V., Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:732–741. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Marsland AL., Gianaros PJ., Abramowitch SM., Manuck SB., Hariri AR. Interleukin-6 covaries inversely with hippocampal grey matter volume in middle-aged adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Carrero JJ., Stenvinkel P., Fellström B., et al. Telomere attrition is associated with inflammation, low fetuin-A levels and high mortality in prevalent haemodialysis patients. J Intern Med. 2008;263:302–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Effros RB. Kleemeier Award Lecture. 2008--the canary in the coal mine: telomeres and human healthspan. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:511–515. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Irie M., Miyata M., Kasai H. Depression and possible cancer risk due to oxidative DNA damage. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Joseph JA., Shukitt-Hale B., Casadesus G., Fisher D. Oxidative stress and inflammation in brain aging: nutritional considerations. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:927–935. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-6967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Forlenza MJ., Miller GE. Increased serum levels of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine in clinical depression. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195780.37277.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wolkowitz OM., Mellon SH., Epel ES., et al. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation and oxidative stress - preliminary findings. PLoS One. In press. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]