Abstract

Clinical trials have been the main tool used by the health sciences community to test and evaluate interventions. Trials can fall into two broad categories: pragmatic and explanatory. Pragmatic trials are designed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in real-life routine practice conditions, whereas explanatory trials aim to test whether an intervention works under optimal situations. Pragmatic trials produce results that can be generalized and applied in routine practice settings. Since most results from exploratory trials fail to be broadly generalizable, the “pragmatic design” has gained momentum. This review describes the concept of pragmatism, and explains in particular that there is a continuum between pragmatic and explanatory trials, rather than a dichotomy. Special focus is put on the limitations of the pragmatic trials, while recognizing the importance for and impact of this design on medical practice.

Keywords: trial, randomized controlled trial, pragmatic, comparative, evidencebased medicine

Abstract

Los ensayos clínicos han sido la principal herramienta empleada por la comunidad de las ciencias de la salud para probar y evaluar las intervenciones. Los ensayos se pueden clasificar en dos grandes categorías: pragmáticos y explicatívos. Los ensayos pragmáticos están diseñados para evaluar la eficacia de las intervenciones en situaciones de la práctica rutinaria en la vida real, mientras que los ensayos explicativos tienen como objetivo probar si una intervención funciona en situaciones óptimas. Los ensayos pragmáticos generan resultados que pueden ser generalizables y aplicables en ambientes de la práctica habitual. Dado que la mayor parte de los resultados de los ensayos explicativos han dejado de ser amplíamente generalizables, el “diseño pragmático” ha cobrado fuerza. Esta revisión describe el concepto de pragmatismo y explica, en particular, que más que una dicotomía hay un continuo entre los ensayos pragmáticos y los explicatívos. Se pone especíal atención a las limitaciones de los ensayos pragmáticos, a la vez que se reconoce la importancia y el impacto de este diseño en la práctica médica.

Abstract

Les études cliniques ont été le principal outil utilisé dans la communauté scientifique médicale pour tester et évaluer les traitements. Les études se répartissent en deux grandes catégories: les études pragmatiques et les études explicatives. Les études pragmatiques sont conçues pour évaluer l'efficacité des traitements dans des conditions de pratique quotidienne de la vie réelle, alors que les études explicatives ont pour but de tester un traitement en conditions optimales. Les études pragmatiques fournissent des résultats qui peuvent être généralisés et appliqués en pratique quotidienne, ce qui n'est pas le cas pour la plupart des études explicatives, et le «schéma pragmatique» a donc le vent en poupe. Cet article décrit le concept de pragmatisme et explique en particulier qu'il existe un continuum entre les études pragmatiques et explicatives, plutôt qu'une dichotomie, il est porté un regard particulier sur les limites des études pragmatiques, tout en reconnaissant leur importance et leur impact sur la pratique médicale.

The health sciences community has spent enormous resources during the past decades on discovering and evaluating interventions, eg, treatments, surgical procedures, and diagnostic and prognostic tests. During this process, robust interventional experiments (trials) have been developed and used to control for the numerous biases (systematic errors) that can infiltrate observational studies.1 Clinical trials, especially randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are designed as experiments with high internal validity - the ability to determine cause-effect relationships. These experiments employ comprehensive designs to control for most, if not all, sources of bias (systematic errors) by means of randomization, blinding, allocation concealment, etc. Usually, extended inclusion and exclusion criteria are used to identify a clearly defined population group of participants who would benefit from the intervention under investigation. Although the above experimental design, if correctly applied, leads to well-controlled trials with statistically credible results, the applicability of these results to real-life practice may be questionable.2 Indeed, the same characteristics that contribute to the high internal validity of a trial (well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, blinding, controlled environment) can hamper its external validity, the ability to generalize the results in an extended population and clinical setting. Although hundreds of trials and RCTs have been performed so far in most clinical conditions, comparing dozens of interventions, there is an increasing expression of doubt as to whether the plethora of available evidence and ongoing data are translatable and usable in real life. Hie need for high-quality, widely applicable evidence is gaining momentum, especially amidst health care policy makers.2-4 The increased costs of interventions and health care in a resource-limited environment have fueled the demand for clinically effective and applicable evidence.

What is a pragmatic trial?

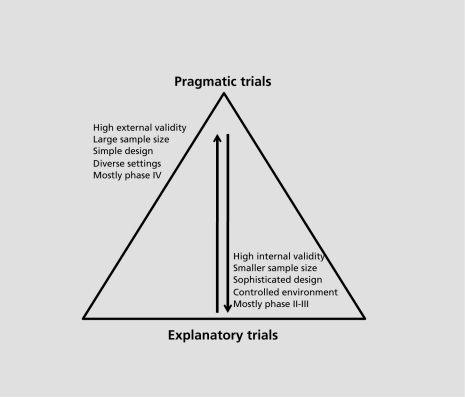

The concern of whether trials produce results applicable to everyday practice was raised many decades ago. Schwartz and Lellouch, back in 1967, coined the terms “explanatory” and “pragmatic” to differentiate trials.5 The term explanatory was used to describe trials that aim to evaluate the efficacy of an intervention in a well-defined and controlled setting, whereas the term pragmatic was used for trials designed to test the effectiveness of the intervention in a broad routine clinical practice. The explanatory trial is the best design to explore if and how an intervention works, and the whole experiment is designed in order to control for all known biases and confounders, so that the intervention's effect is maximized. Usually the intervention under examination is compared with a placebo or with another active treatment. The pragmatic trial, on the other hand, is designed to test interventions in the full spectrum of everyday clinical settings in order to maximize applicability and generalizability. The research question under investigation is whether an intervention actually works in real life. The intervention is evaluated against other ones (established or not) of the same or different class, in routine practice settings. Pragmatic trials measure a wide spectrum of outcomes, mostly patient-centered, whereas explanatory trials focus on measurable symptoms or markers (clinical or biological). Figure 1 illustrates some main differences between pragmatic and explanatory trials.

Figure 1. Schematic of the relationship between explanatory and pragmatic trials. The wide base of the pyramid depicts the relatively higher proportion of explanatory trials.

Generally, the explanatory trials focus towards homogeneity, so that the errors and biases will influence the results as little as possible, whereas pragmatic trials are a race towards maximal heterogeneity in all aspects, eg, patients, treatments, clinical settings, etc. In order to overcome the inherited heterogeneity, which leads to dilution of the effect, pragmatic trials must be large enough (to increase power to detect small effects) and simple in their design. Simple trials are easier to plan, perform, and follow up.

Policy makers have an active interest in pragmatic trials, since these are designed to answer the question most relevant to a decision maker's agenda: comparative effectiveness of interventions in the routine practice. Along with the implementation of cost-effectiveness analyses, pragmatic trials can inform policy makers and health care providers of a treatment's cost in real-life situations. Thus, decision makers are active partners in the design of the pragmatic trials.6,7

The tree or the forest?

The distinction between an explanatory and a pragmatic trial in real life is not that easy. Most trials have both explanatory and pragmatic aspects. Gartlehner et al proposed a set of seven domains to evaluate the explanatory or pragmatic nature of a trial.8 Although they acknowledged that efficacy (explanatory) and effectiveness (pragmatic) exist in a continuum, they used a binary system (yes/no) in the evaluation of these domains. Thorpe et al, a few years later, introduced the pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS) tool.9 PRECIS was created to enable investigators to design trials acknowledging the explanatory/pragmatic continuum in 10 domains:

Eligibility criteria

Flexibility of the experimental intervention

Practitioner expertise (experimental)

Flexibility of the comparison intervention

Practitioner expertise (comparison)

Follow-up intensity

Outcomes

Participant compliance

Practitioner adherence

Primary outcomes.

To illustrate, a very pragmatic trial across these 10 domains would be:

There are no inclusion or exclusion criteria

Practitioners are not constricted by guidelines on howapply the experimental intervention

The experimental intervention is applied by all practitioners, thus covering the full spectrum of clinical settings

The best alternative treatments are used for comparison with no restrictions on their application

The comparative treatment is applied by all practitioners, covering the full spectrum of clinical settings

No formal follow-up sections

The primary outcome is a clinical meaningful one that does not require extensive training to assess

There are no plans to improve or alter compliance for the experimental or the comparative treatment

No special strategy to motivate practitioner's adherence to the trial's protocol

The analysis includes all participants in an intentionto-treat fashion.

The idea of the explanatory continuum is very intriguing, although rather challenging to apply and quantify. Some modifications of the PRECIS tool have been developed. Koppenaal et al, for example, adapted the PRECIS tool in the assessment of systematic reviews, introducing a scale from 1 to 5 for the 10 domains (1 is for explanatory and 5 for the pragmatic end).10 Using the ordinal scale system, they demonstrated how their modification (named the PR-tool) could quantify the continuum per domain and study, thus giving an overall summary for systematic reviews. The study by Tosh et al11 in this issue of Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience adapts PRECIS into the Pragmascope tool to help the appraisal of RCTs by mental health researchers. They use a scoring system from 0 to 5 (0 is used when the domain can not be evaluated) to quantify the explanatory continuum, and they give recommendations on translation of a trial's score. A modification of the PRECIS' “wheel” plot, a visualization of the continuum in the 10 domains, is also presented, and the reader is encouraged to examine it.

The rise of “pragmatism”

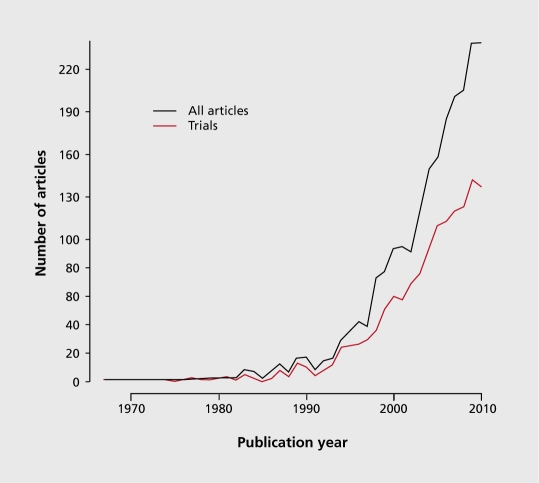

Although the first article introducing the concept of pragmatism was published in 1967,5 the scientific community has only recently started to be aware of the issue. 6,12-14 Terms like pragmatic and its synonyms, practical and naturalistic, have been used at an increasing rate to express the need for more evidence that is applicable in routine clinical settings (the term naturalistic is also used to describe observational studies with pragmatic aspects). Figure 2 illustrates this etymologic usage trend by plotting the appearance of the words pragmatic or naturalistic along with the word “trial” in articles indexed in MEDLINE. Although the search used to identify these articles is neither sensitive (not all pragmatic trials and articles on the subject are included) nor specific (the retrieved records might not be in fact pragmatic trials or discuss issues on the subject), there is a clear indication that the health sciences community is more sensitized to the whole pragmatism topic. Also encouraging is the increasing rate of clinical trials (as defined by MEDLINE, again this is neither sensitive or specific) that use the words pragmatic and naturalistic in the title or the abstract, depicted in red in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Articles per year catalogued in MEDLINE that have in the title or abstract the words pragmatic or naturalistic and the word trial. The red line represents the articles that are tagged from Medline as “Clinical Trial” or “Randomized Controlled Trial”. The exact search was “pragmatic* [tiab] OR naturalistic* [tiab]) AND trial” and was performed on May 5th 2011.

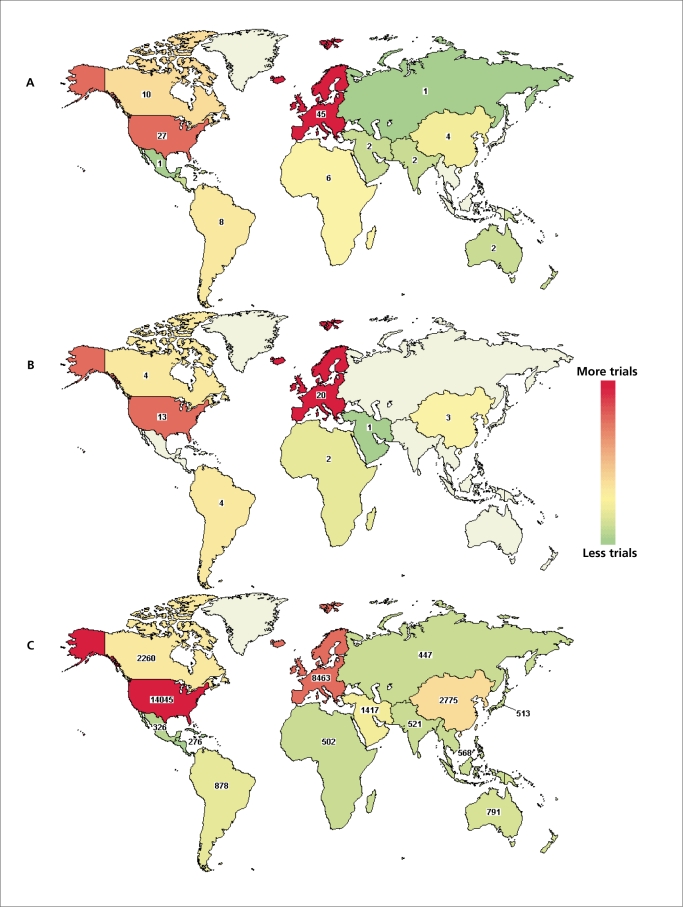

The majority of the scientific peer-reviewed journals nowadays require registration of clinical trials prior to their submission for publication. The ClinicalTrials.gov registry (www.ClinicalTrials.gov) is one of the most widely accepted, and follows an open-access philosophy. Interestingly, only a small proportion (n=111) of the overall studies indexed in the registry (n=106 927 on May 5 2011) have used a term like pragmatic or naturalistic to describe interventional studies (Figure 3A). An important observation is that 47 of these 111 trials are described as “Open” (still recruiting, ongoing, or not closed yet, Figure 3B), whereas the database includes 28 882 open interventional studies (Figure 3C). Another notable observation is that the distribution of the “pragmatic” trials seems to be reversed compared with the overall open ones: Europe is the region with the highest number of “pragmatic” trials, whereas the USA, first in the overall number of ongoing trials, is in second place. Again, this is neither a sensitive nor a specific method to identify pragmatic trials; it serves as an indication and stimulus for the reader, rather than robust evidence.

Figure 3. Interventional trials in the ClinicalTrials.gov registry. A. Trials using the words “pragmatic” and/or “naturalistic” and which claim to be interventional (n=111). B. Number of trials among the 111 presented in panel A that are tagged as “Open” (still recruiting, ongoing or not closed yet, n=47). C. Trials in the ClinicalTrials.gov registry that claim to be interventional and are tagged as “Open” (n=28 882). The search was performed on May 5th 2011 using the terms “pragmatic* OR naturalistic*.” Colors indicate the intensity of studies in majorworld regions. Counts give the exact number of studies per region.

The pragmatism movement is materialized through research, but the driving power is the health-care policy makers and the societies in general. In 2009 the USA Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), a multi-billion dollar stimulus package, which included $1.1 billion for Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER). 15 The two main objectives of the CER Initiative were “to evaluate the relative effectiveness of different health care services and treatment options” and “to encourage the development and use of clinical registries, clinical data networks, and other forms of electronic data to generate outcomes data.” The Initiative has already published a report in which 100 national health priorities are described, eg, “Compare the effectiveness of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments in managing behavioral disorders in people with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in home and institutional settings.”

Limitations and criticism

The cornerstone of a pragmatic trial is the ability to evaluate an intervention's effectiveness in real life and achieve maximum external validity, ie, be able to generalize results to many settings. But what is the definition of “real life” when it comes to health sciences? Will the results of a pragmatic trial that tests a treatment in the primary care setting in UK be applicable in an East-Asian country, or even another European country? Rothwell16 illustrates such a case in the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST),17 a RCT of endarterectomy for recent carotid stenosis. The differences in the clinical settings between countries resulted in heterogeneity in the investigation time of a new stroke, thus affecting the overall effectiveness of the endarterectomy. Furthermore, even within the same country's health system it is unknown whether similar clinical settings are indeed comparable. Evidence of a treatment's effectiveness in a given setting does not guarantee that it will also be effective in another one, and vice versa. Empirical evidence on the topic is limited. The little systematic evidence available so far has indicated only the lack of external validity in trials,16 not how comparable different clinical settings are or how easy it is to transfer results from one to another. Moreover, there is no hard evidence that an increase of a trial's “within-study” heterogeneity, eg, variability of practitioners, patient and health care delivery, will indeed increase the external validity by lowering the “between-study” heterogeneity among different trials.

A well-studied intervention, with high-quality evidence from robustly designed and performed explanatory trials, which is effective in a specific combination of practitioners/patients, will probably be less effective in extended populations. For example, a high-tech surgical procedure, which needs specialized equipment and trained personnel, in most cases will be less effective in other (suboptimal) settings. This can cause a dilution of effect, and a pragmatic trial will find this intervention to be ineffective in the broader “real-life” setting. On the other hand, some treatments with moderate effects might benefit from the lack of blindness and allocation concealment, and patient preferences or beliefs can influence the outcome of the study. Empirical studies on this subject have demonstrated that trials lacking or with inappropriate blinding and/or allocation concealment often yield (erroneously) more statistically significant results than RCTs, which are better controlled.18-20 Whereas a pragmatic trial can inform on the overall performance of a treatment, in situations as above it will be very difficult to identify the specific components (or even biases) that explain this effectiveness. Post-hoc exploratory subgroup analyses will have to be employed, and inform future trials. Issues like these need to be considered in the planning phase of the trial, in order to identify the possible moderators of effects and plan a priori subgroup analyses, while keeping the trial design as simple as possible.21 Some promising study designs have been proposed that could be used to identify differential effectiveness in subpopulations or the influence of systematic errors in pragmatic trials, leveraging also the benefits of randomization.22

Pragmatic trials aim to evaluate many interventions and compare their effectiveness. Explanatory trials can also do the same thing; however there is a systematic lack of comparative (head-to-head) trials in the health science literature.23 Use of placebo-controlled designs is common, but even when a trial examines an experimental treatment against the established ones, the most common implemented design is a noninferiority or equivalence one, ie, the experimental treatment is tested for whether is not worse than, or the same as, the established one, respectively. This “preference” can be explained less by the explanatory nature of the trials and more by the role of the industry24 and the current regulations for drug approval.25

Since pragmatic trials examine treatment effects of many interventions in a plethora of settings, large sample sizes and long follow-up periods are dictated in order to produce reliable and (re)usable evidence.14,21 However, the cost of very large trials can be enormous. For instance, the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT),26 a well-planned RCT which evaluated 4 antihypertensive treatments, took 8 years to finish and the cost was more than 100 million (almost 10% of the overall CER Initiative's budget).25 The extensive cost of trials (experimental designs) means that observational designs, although not less costly, and, mostly, data-mining methods can be used to answer some generalizability questions. The CER Initiative has provision for funding of such designs; however, observational studies are prone to errors and confounding27,28 In such cases, employment of innovative technologies (eg, cloud computing) and open access of the available data (with respect to ethical considerations and privacy) will help the research community to safeguard itself and also boost research discovery.29

Health-care policy makers probably are to benefit the most from the pragmatism concept. The availability of comparative data from routine practice with cost-effectiveness data will help policy makers to efficiently allocate resources and manpower. Nevertheless, there is no indication that decision makers will have the same priorities or interpretation of the same results.30 Even so, policy makers might have different points of view and hierarchy systems than clinicians and/or patients. A “one-size-fits-all” approach might not serve anyone at the end of the day.30 Moreover, in the light of patientcentered medicine, the knowledge that a treatment is effective in a routine setting does not give specific quantifiable answers under individual cases, eg, what is the effect of the treatment in a 70-year old woman with dementia and type 2 diabetes?

Finally, in very few areas can 100% pragmatic trials really be performed. Pragmatism is a quality or attribute of the trial that is not simply dichotomous, ie, absent or present. This continuous nature implies that most trials will have some aspects towards the explanatory end and others towards the pragmatic one. Even trials that claim to be pragmatic in their titles, like the ones in Figure 1, can be as pragmatic as the average trial in some respects. Koppenaal et al10 evaluated two reviews in their adaptation of PRECIS to systematic reviews: one that expected to have trials with more pragmatic characteristics and another one expected to include trials with more explanatory ones. They observed that indeed the pragmatic systematic review had a higher average score in the 10 PRECIS domains (higher values imply that the study/review is more pragmatic), however in one domain, the participant compliance, the pragmatic systematic review had a (not statistically significant) lower value than the explanatory review (3.0 vs 3.2).

Implications for evidence-based medicine

Like any other concept, pragmatic trials are not free of limitations. However, the whole idea of applicable and gene rateable research is very appealing and of benefit to the health sciences community. Sensitizing policy makers, practitioners, and even patients, and making them part of the research culture is a positive step. But should explanatory trials cease to exist? A trial can be designed to have some aspects that are more pragmatic than explanatory, and vice versa, but some trials must be as explanatory as possible. New interventions and identification of cause-effect relationships will always need experiments with high internal validity. Even the results of pragmatic trials will include many post-hoc exploratory analyses, which will require in turn explanatory trials to verify them. Thus, in terms of absolute numbers there will always be far more explanatory trials than pragmatic ones, with manytrials lying in the continuum between them Figure 1. Pragmatic trials are not here to replace the existed explanatory ones, rather to complement them.

Randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews are two important and well-recognized tools in the evidence based medicine era.31 Systematic reviews, especially from the Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.org), have highlighted the extensive heterogeneity in available data across topics. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses could incorporate a PRECIS score for synthesized trials and help the systematic mapping of the pragmatism in published research. The scientific community could also benefit from the wide adoption of meta-analysis of multiple treatments (MTM), in which information from indirect comparisons of treatments is used where head-to-head trials are limited or nonexistent.32 Evidence from MTMs, using the proper statistical techniques, can even sort interventions in terms of effectiveness.33 Medical journals could adopt tools that measure pragmatic aspects of trials, like the CONSORT extension for pragmatic trials34 or an adaptation of the PRECIS tool. 9 All of the above could help policy and decision makers prioritize interventions and medical conditions in which rigorous data with practical aspects is sparse.

Conclusion

Pragmatic trials are conducted in real-life settings encompassing the full spectrum of the population to which an intervention will be applied. The “pragmatic design” is an emerging concept, and it is here to stay. The scientific community, practitioners, and policy makers, as well as health care recipients, should be sensitized to the “pragmatic” concept and should even demand more evidence applicable to real-life settings. However, this process should not be done at expense of exploratory trials. We need both concepts to answer the complicated problems lying ahead of us.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Rany Salem, Tiago V. Pereira, and Karla Soares-Weiser for comments and suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grimes DA., Schulz KF. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet. 2002;359:248–252. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwarenstein M., Oxman A. Why are so few randomized trials useful, and what can we do about it? J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1125–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss NS., Koepsell TD., Psaty BM. Generalizabilityof the results of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:133–135. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treweek S., Zwarenstein M. Making trials matter: pragmatic and explanatory trials and the problem of applicability. Trials. 2009;10:37. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz D., Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1967;20:637–648. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tunis SR., Stryer DB., Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA. 2003;290:1624–1632. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maclure M. Explaining pragmatic trials to pragmatic policymakers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:476–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gartlehner G., Hansen RA., Nissman D., et al. A simple and valid tool distinguished efficacy from effectiveness studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1040–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorpe KE., Zwarenstein M., Oxman AD., et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koppenaal T., Unmans J., Knottnerus JA., Spigt M. Pragmatic vs. explanatory: an adaptation of the PRECIS tool helps to judge the applicability of systematic reviews for daily practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011. In press doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tosh G., Soares-Weiser K., Adams C. Pragmatic vs. explanatory trials: the PRAGMASCOPE tool to help measuring differences in protocols of mental health randomized controlled trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:209–215. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.2/gtosh. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlton BG. Understanding randomized controlled trials: explanatory or pragmatic? Earn Pract. 1994;11:243–244. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE., Magid DJ., Beck A., et al. Practical clinical trials for translating research to practice: design and measurement recommendations. Med Care. 2005;43:551–557. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163645.41407.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macpherson H. Pragmatic clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prioritization. CoCR. Institute of Medicine Initial National Priorities for Compaiative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet. 2005;365:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masuhr F., Busch M., Einhaupl KM. Differences in medical and surgical therapy for stroke prevention between leading experts in North America and Western Europe. Stroke. 1998;29:339–345. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood L., Egger M., Gluud LL., et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2008;336:601–605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odgaard-Jensen J., Vist GE., Timmer A., et al. Randomisation to protect against selection bias in healthcare trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;4:MR000012. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000012.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pildal J., Hrobjartsson A., Jorgensen KJ., et al. Impact of allocation concealment on conclusions drawn from meta-analyses of randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:847–857. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.March J., Kraemer HC., Trivedi M., et al. What have we learned about trial design from NIMH-funded pragmatic trials? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2491–2501. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Relton C., Torgerson D., O'Cathain A., Nicholl J. Rethinking pragmatic randomised controlled trials: introducing the “cohort multiple randomised controlled trial” design. BMJ. 2010;340:c1066. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.loannidis JPA. Indirect comparisons: the mesh and mess of clinical trials. Lancet. 2006;368:1470–1472. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lathyris DN., Patsopoulos NA., Salanti G., loannidis JP. Industry sponsorship and selection of comparators in randomized clinical trials. Eur J Clin invest. 2010;40:172–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg NH., Schneeweiss S., Kowal MK., Gagne JJ. Availability of comparative efficacy data at the time of drug approval in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305:1786–1789. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Group AOaCftACR. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pocock SJ., Collier TJ., Dandreo KJ., et al. Issues in the reporting of epidemiological studies: a survey of recent practice. BMJ. 2004;329:883. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38250.571088.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawlor DA., Davey Smith G., Kundu D., et al. Those confounded vitamins: what can we learn from the differences between observational versus randomised trial evidence? lancet. 2004;363:1724–1727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Djulbegovic M., Djulbegovic B. Implications of the principle of question propagation for comparative-effectiveness and “data mining” research. JAMA. 2011;305:298–299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karanicolas PJ., Montori VM., Schunemann H., Guyatt GH. “Pragmatic” clinical trials: from whose perspective? Evid Based Med. 2009;14:130–131. doi: 10.1136/ebm.14.5.130-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patsopoulos NA., Analatos AA., loannidis JP. Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. JAMA. 2005;293:2362–2366. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu G., Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med. 2004;23:3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cipriani A., Furukawa TA., Salanti G., et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:746–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zwarenstein M., Treweek S., Gagnier JJ., et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337:a2390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]