Abstract

In the pragmatic-explanatory continuum, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) can at one extreme investigate whether a treatment could work in ideal circumstances (explanatory), or at the other extreme, whether it would work in everyday practice (pragmatic). How explanatory or pragmatic a study is can have implications for clinicians, policy makers, patients, researchers, funding bodies, and the public. There is an increasing need for studies to be open and pragmatic; however, explanatory trials are also needed. The previously developed Pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS) was adapted into the Pragmascope tool to assist mental health researchers in designing RCTs, taking the pragmatic-explanatory continuum into account. Ten mental health trial protocols were randomly chosen and scored using the tool by three independent raters. Their results were compared for consistency and the tool was found to be reliable and practical. This preliminary work suggests that evaluating different domains of an RCT at the protocol level is useful, and suggests that using the Pragmascope tool presented here might be a practical way of doing this.

Keywords: clinical trials as topic/methods, practice guidelines as topic, randomized controlled trials as topic/methods, research design, mental health

Abstract

En el continuo pragmático-explicativo, un ensayo controlado randomizado (ECR) puede investigar por una parte si un tratamiento podría funcionar en circunstancias ideales (explicativas) y por otra si podria funcionar en la práctica diaria (pragmático). Cuan explicativo o pragmático sea un estudio, puede tener repercusiones para los clinicos, los políticos, los pacientes, los investigadores, los organismos de financiamiento y el público. Hay una necesidad creciente de que los estudios sean abiertos y pragmáticos; sin embargo, también son necesarios los ensayos explicativos. PRECIS, el resumen del indicador del continuo pragmático-explicativo que se había desarrollado con anterioridad, se adaptó al instrumento Pragmascope para ayudar a los investigadores de salud mental en los diseños de ECR, tomando en consideración el continuo pragmático-explicativo. Se eligieron randomizadamente diez protocolos de ensayos de salud mental y se les asignó puntaje mediante el instrumento por tres evaluadores independientes. Sus resultados se compararon en cuanto a consistencia y se encontró que el instrumento fue confiable y práctico. Este trabajo preliminar sugiere que es útil la evaluación de diferentes aspectos de un ECR a nivel del protocolo y propone que el empleo del instrumento Pragmascope presentado aquí sería una forma práctica de hacerlo.

Abstract

Dans le continuum pragmatique-explicatif, une étude contrôlée randomisée (ECR) peut d'un côté analyser l'efficacité d'un traitement en circonstances idéales (explicatives) ou d'un autre côté son efficacité dans la pratique quotidienne (pragmatique). Qu'une étude soit explicative ou pragmatique, elle peut avoir des implications pour les médecins, les responsables politiques, les patients, les chercheurs, les organismes de financement et le public. Les études doivent de plus en plus être ouvertes et pragmatiques, mais les études explicatives sont aussi nécessaires. L'indicateur de continuum pragmatique - explicatif PRECIS (Pragmatic-explanatory conti nuum indicator summary) développé antérieurement a été adapté sous forme de l'outil PRAGMASCOPE pour aider les chercheurs en santé mentale à concevoir des ECR, en prenant en compte ledit continuum. Dix protocoles d'études en santé mentale ont été choisis et cotés au hasard grâce à l'outil, par trois évaluateurs indépendants. Leurs résultats ont été comparés pour évaluer leur cohérence et l'outil s'est avéré fiable et pratique. Ce travail préliminaire suggère que l'évaluation des différents domaines des ECR au niveau du protocole est utile et que l'utilisation du PRAGMASCOPE présenté ici pourrait être un moyen pratique de le faire.

Background

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) has long been recognized as the most robust, technique for evaluating the effects of mental health care interventions.1 Sometimes these trials are impossible, sometimes unethical, and sometimes impractical. The first, RCT was the 1948 Medical Research Council Streptomycin Trial.2 In the austere times of bankrupt, post-war England, just as the National Health Service was being established, it, was suggested that, a new drug would be of value for treatment of tuberculosis. The only equitable way to distribute this scarce resource was through randomization and then, by the establishment of good evidence, to encourage those funding health care to support its use. There are many interesting and important examples preceding this date,3 but this landmark and courageous trial radically changed the pathway of evaluation of medical treatments.

Mental health has a fine tradition of using trials to evaluate treatments.4 The MRC Streptomycin trial coincided with the discovery of psychoactive compounds that were potentially therapeutic, as well as an increasing push towards deinstitutionalization. Mental health professionals discovered, discussed, and, largely, embraced the use of RCTs. Up to the advent of antipsychotic drugs such as chlorpromazine, psychiatric care had been likened to “little more than zoo keeping”5 and, perhaps because of that stinging criticism, those undertaking the trials did not necessarily follow the path of that first tuberculosis trial. Factors combined to largely direct mental health trials along another route. There was the yearning for rigorous science, collective subspecialty insecurity, and also the needs of regulatory authorities. Mental health trials drifted towards use of as rigorous diagnoses as possible, rather rigid regimens of care and use of fine-grained outcome measures that, are not usually part of routine practice. This planted the RCT firmly in the realm of researchers, and there it has stayed. The needs of regulatory authorities did have to be met, but, there was less consideration of needs of clinicians and of recipients of care and their families.

This was not at all unique to mental health, but it. took leaders in the fields of cancer care,6 heart disease,7 and perinatal medicine8 to recall and refine the techniques of generous inclusion, simple treatment, and routine data collection that underpinned the MRC trial of 1948. Many examples now exist in these areas of RCTs where entry criteria are broad and encompass as many relevant people as possible, the treatment packages are those that would be given in everyday care, and outcomes are essentially routinely recorded data. Examples of such open work were rare in mental health until relatively recently. The description of “pragmatic” or “practical” is increasingly employed of trials in psychiatry or psychology but there are clearly different interpretations of what, this really means.

A recent series of papers has highlighted the problems in interpretation of the explanatory/pragmatic domains in trials and presented some practical solutions.9 It is not a simple continuum from explanatory through to pragmatic. There are many elements of design that should be considered to allow a judgment to take place about whether a randomized trial is investigating whether, in ideal circumstances, a treatment could work (explanatory) or, at the other extreme, whether this accessible treatment would work in everyday practice (pragmatic). This is not a purely academic exercise. There are good reasons to make these judgments. To use one example, funders, on receiving a proposal, may wish to consider whether the proposed trial fits with the ethos in which that support was proffered. For example one funding body may be interested in discovering potentially new treatments. In this instance, explanatory studies, undertaken in very rigorous circumstances with fine measures of outcome to highlight, any - even modest, - effects, may be best. On the other hand, another funder, using public money, may wish to consider whether the study is likely to produce evidence of practical importance regarding accessible treatments relevant, to the majority of people suffering with the condition in that, community.10 Here a much more pragmatic study would be desired. How explanatory or pragmatic a study (or a group of studies) is has also obvious and direct implications for clinicians, policymakers, patients, and the public.

The main goal of this study is to adapt the instrument described by Thorpe et al9 (PRECIS) to assist, researchers in making those judgments in the protocol stage of RCTs in mental health (the Pragmascope tool).

Methods

The Pragmascope tool

This tool is based on the ten domains described in the development, of the Pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS).9 It can be used to assess applicability of results from any given RCT, based on what, was planned at the protocol stage.

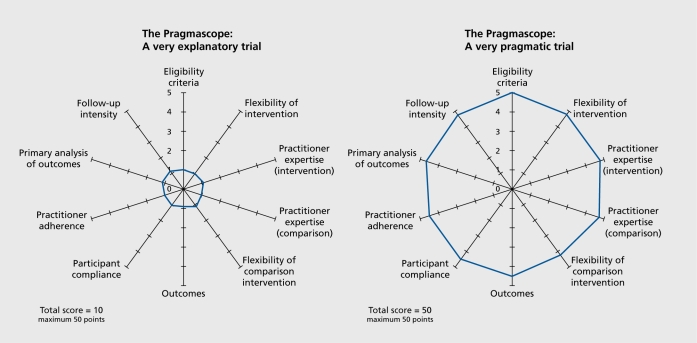

Each included RCT protocol11-19 was scored in ten domains by three independent, reviewers (GT, KSW, CEA). The reviewers made a judgment and rated the protocol from 1 (most explanatory) to 5 (most, pragmatic) by reading the details of the protocol. If the protocol did not contain any information on which to base the decision, these domains were rated as zero. The average scores for each included protocol were placed on the wheel diagram and the dots joined for visual clarity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples of output. Reproduced from ref 9: Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, Treweek S, Furberg CD, Altman DG, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:464-475. Copyright © 2009 Elsevier.

Selection of RCT protocols

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register and Medline (November 2010) for references of RCT protocols and chose a random sample of 10 protocols dealing with schizophrenia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorders, and psychiatric rehabilitation.11-19

Scoring the Pragmascope tool

Three independent reviewers (GT, KSW, CEA) scored each included RCT protocol. The overall score can be from 0 to 50 and a diagram illustrating how open (pragmatic) or restrictive (explanatory) the study is likely to be was created using the average score of the three independent reviewers.

Our initial interpretation of the scores was of 0 to 30 for an explanatory study investigating whether the experimental intervention will work in ideal circumstances and a total score >35 for a more pragmatic study focusing mostly on whether, in routine practice, an intervention has a meaningful effect. A total score between 31 and 39 were interpreted as an interim where trial design balances pragmatic and explanatory domains.

Data analysis

Mean and variance were calculated for each domain of the Pragmascope tool for each included RCT protocol using STATA (version 10). In addition, a weighted kappa for the domains was calculated using R.

Results

Table I presents the average score of the three raters in each one of the domains for each RCT protocols with a judgment based on the scores. Reliability among the three independent raters was high (weighted Kappa =0.72 for categories 0-30, 31-39, 40-50) suggesting that this cluster of judgments might be useful to highlight and quantify important, issues during the protocol stage of an RCT.

Table I. Average score of three raters for each one of the domains of the RCT protocol.

| Domain | ACHIEVE14 | CATIE11 | CCEST17 | DYD18 | ERP16 | FIAT19 | PTSD- Yoga20 | ROMT15 | SPCCD13 | TREC - SAVE |

| (Low) | (Low) | (Low) | (Low) | (Low) | (High) | (Moderate) | (Moderate) | (Low) | (High) (unpublished) | |

| Eligibility criteria | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Flexibility of intervention | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Practitioner expertise (intervention) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Practitioner expertise (comparison) | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Flexibility of comparison intervention | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Outcomes | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Participant compliance | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Practitioner adherence | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Primary analysis of outcomes | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Follow-up intensity | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Total Average score | 23 | 25 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 43 | 34 | 34 | 28 | 45 |

We recognize that validity is a more problematic issue, as this does depend on the rater's perspective, but, work is ongoing involving raters from very different backgrounds. In any case, we concur that, consideration of these domains is useful9 and suggest that the Pragmascope is one practical way of doing this.

Discussion

The world of RCTs has changed remarkably in the last 10 years. Systematic reviewing of trials, now industrially undertaken through initiatives like the Cochrane Collaboration,20 has highlighted issues with poor design and inconsistent reporting. These systematic reviews are potent to guide care but, are undermined by trial evidence that is difficult or impossible to apply in the real world. For mental health, studies of increasing pragmatism are now being designed and undertaken.21-23 Such pragmatic, real-world, practical design can be dovetailed within explanatory studies or sit independently. With maintained systematic reviews guiding practice,21 transparent priority setting for research funding for evaluative research,3 and the push towards defining core out come measures of agreed relevance in trials,24 a great, increase in pragmatic trial activity is likely. Of course explanatory trials have an important place in the portfolio of research, but. the rigorously undertaken but highly pragmatic trial will give us the opportunity to learn much more about, the real effects of the potent, treatments we give.

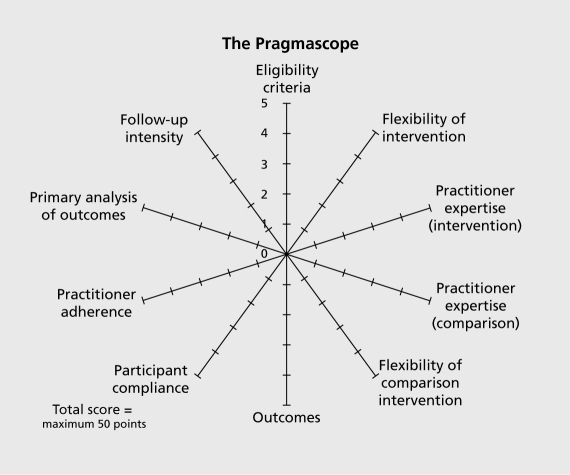

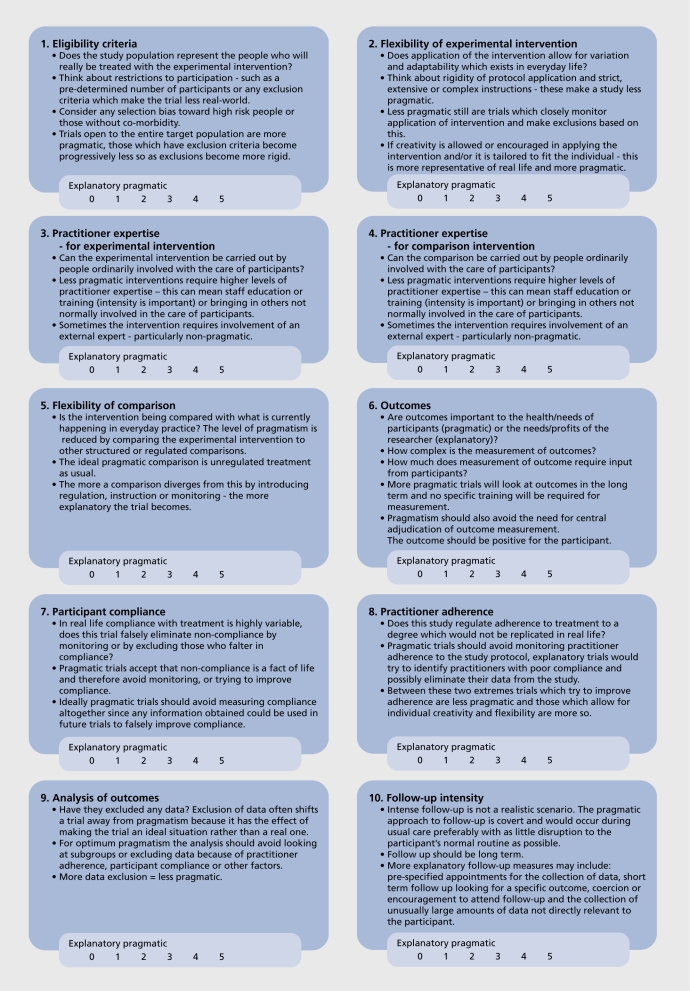

Appendix. The Pragmascope (Figures 2). Explanation: This tool is based on ten domains described in the development of the Pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS).9 It can be used to assess applicability of results from any given randomized controlled trial. Instructions: For each of the ten domains please make a judgement and rate the protocol from 1 (most explanatory) to 5 (most pragmatic). Your score should be based on a thorough reading of the protocol. If the protocol does not contain any information on which to base your decision we advise a default score of zero. If you feel your scores require justification - please make comments in box provided. Mark score on relevant part of the diagram and join the dots. Results: The scoring can give you an overall score (0-50) and a diagram illustrating how open (pragmatic) or restrictive (explanatory) the study is likely to be. Interpretation: Figure 1 (see main text) demonstrates an explanatory study investigating whether the experimental intervention will work in ideal circumstances (total score 0-15) and a more pragmatic study focusing mostly on whether, in routine practice, an intervention has a meaningful effect (total score >35). A total score between 16 and 35 suggest an interim where trail design balances pragmatic and explanatory domains.

Appendix. The Pragmascope (Figures 3).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr K. Thorpe for consideration of our rating tool, and Dr B. Park for help calculating Kappa.

Contributor Information

Graeme Tosh, Psychiatrist, East Midlands Workforce Deanery, Nottingham, UK.

Karla Soares-Weiser, Director, Enhance Reviews Ltd, Oxford, UK.

Clive E. Adams, Professor, Institute of Mental Health, University of Nottingham, UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. Evaluation of methods for the treatment of mental disorders. Report of a WHO Scientific Group on the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 1991;812:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medical Research C. Streptomycin treatment of tuberculous meningitis. Lancet. 1948;1:582–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Documenting the evolution of fair tests. Available at: http://www.jameslindlibrary.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thornley B., Adams C. Content and quality of 2000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 50 years. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 1998;317:1181–1184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner T. Chlorpromazine: unlocking psychosis. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2007;334(suppl 1):s7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correa C., McGale P., Taylor C., et al. Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Nat Cancer Inst Monographs. 2010;2010:162–177. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baigent C., Collins R., Appleby P., Parish S., Sleight P., Peto R. ISIS-2: 10 year survival among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction in randomised comparison of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither. The ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 1998;316:1337–1343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Which anticonvulsant for women with eclampsia? Evidence from the Collaborative Eclampsia Trial. Lancet. 1995;345:1455–1463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorpe KE., Zwarenstein M., Oxman AD., et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peto R., Collins R., Gray R. Large-scale randomized evidence: large, simple trials and overviews of trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;703:314–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroup TS., McEvoy JP., Swartz MS., et al. The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:15–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buszewicz M., Griffin M., McMahon EM., Beecham J., King M. Evaluation of a system of structured, pro-active care for chronic depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casagrande SS., Jerome GJ., Dalcin AT., et al. Randomized trial of achieving healthy lifestyles in psychiatric rehabilitation: the ACHIEVE trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gold C., Rolvsjord R., Aaro LE., Aarre T., Tjemsland L., Stige B. Resourceoriented music therapy for psychiatric patients with low therapy motivation: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobban F., Gamble C., Kinderman P., et al. Enhanced relapse prevention for bipolar disorder--ERP trial. A cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the feasibility of training care coordinators to offer enhanced relapse prevention for bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morriss R., Marttunnen S., Garland A., et al. Randomised controlled trial of the clinical and cost effectiveness of a specialist team for managing refractory unipolar depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray E., McCambridge J., Khadjesari Z., et al. The DYD-RCT protocol: an on-line randomised controlled trial of an interactive computer-based intervention compared with a standard information website to reduce alcohol consumption among hazardous drinkers. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:306. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Priebe S., Burton A., Ashby D., et al. Financial incentives to improve adherence to anti-psychotic maintenance medication in non-adherent patients - a cluster randomised controlled trial (FIAT). BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telles S., Singh N., Joshi M., Balkrishna A. Post traumatic stress symptoms and heart rate variability in Bihar flood survivors following yoga: a randomized controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalmers I. The Cochrane collaboration: preparing, maintaining, and disseminating systematic reviews of the effects of health care. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;703:156–63; discussion 63-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones PB., Barnes TRE., Davies L., et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect on Quality of Life of second- vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1079–1087. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Group TC. Rapid tranquillisation for agitated patients in emergency psychiatric rooms: a randomised trial of midazolam versus haloperidol plus promethazine. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2003;327:708–713. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieberman JA., Stroup TS., McEvoy JP., et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209–1023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.COMET Initiative - NWHTMR - University of Liverpool. Available at: http://www.liv.ac.uk/nwhtmr/comet/comet.htm. [Google Scholar]