Dendritic cell responsiveness to type I interferon is required for the generation of antitumor T cell responses and tumor rejection.

Abstract

Cancer immunoediting is the process whereby the immune system suppresses neoplastic growth and shapes tumor immunogenicity. We previously reported that type I interferon (IFN-α/β) plays a central role in this process and that hematopoietic cells represent critical targets of type I IFN’s actions. However, the specific cells affected by IFN-α/β and the functional processes that type I IFN induces remain undefined. Herein, we show that type I IFN is required to initiate the antitumor response and that its actions are temporally distinct from IFN-γ during cancer immunoediting. Using mixed bone marrow chimeric mice, we demonstrate that type I IFN sensitivity selectively within the innate immune compartment is essential for tumor-specific T cell priming and tumor elimination. We further show that mice lacking IFNAR1 (IFN-α/β receptor 1) in dendritic cells (DCs; Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice) cannot reject highly immunogenic tumor cells and that CD8α+ DCs from these mice display defects in antigen cross-presentation to CD8+ T cells. In contrast, mice depleted of NK cells or mice that lack IFNAR1 in granulocytes and macrophage populations reject these tumors normally. Thus, DCs and specifically CD8α+ DCs are functionally relevant targets of endogenous type I IFN during lymphocyte-mediated tumor rejection.

The ability of the immune system to function as an extrinsic tumor suppressor and effectively eliminate, control, and/or sculpt developing tumors forms the basis of the cancer immunoediting hypothesis (Shankaran et al., 2001; Dunn et al., 2002, 2004). There is strong experimental support for all three phases of cancer immunoediting, elimination, equilibrium, and escape, and many of the key cellular mediators and immune effector molecules involved in host protection from tumor development have been identified (Dunn et al., 2006; Smyth et al., 2006; Koebel et al., 2007; Schreiber et al., 2011; Vesely et al., 2011). The IFNs, both type I (IFN-α/β) and type II (IFN-γ), have emerged as critical components of the cancer immunoediting process, and work is ongoing to define their respective roles in promoting antitumor immune responses.

Early studies supporting the existence of cancer immunoediting revealed an important function for IFN-γ in suppressing tumor development in models of both tumor transplantation and primary tumor induction (Dighe et al., 1994; Kaplan et al., 1998; Shankaran et al., 2001; Street et al., 2001, 2002). Specifically, IFN-γ was found to induce effects on both tumor cells (Dighe et al., 1994; Kaplan et al., 1998; Shankaran et al., 2001; Dunn et al., 2005) and host cells (Mumberg et al., 1999; Qin and Blankenstein, 2000; Qin et al., 2003). Subsequently, an essential function for endogenous type I IFN in cancer immunoediting was established (Dunn et al., 2005; Swann et al., 2007). Gene-targeted mice lacking the type I IFN receptor developed more carcinogen-induced primary tumors than WT control mice (Dunn et al., 2005; Swann et al., 2007), and antibody-mediated blockade of the IFN-α/β receptor in WT hosts abrogated rejection of immunogenic transplanted tumors (Dunn et al., 2005). The activity of endogenous type I IFN was mediated not by its direct effects on the tumor but by its actions on host cells, specifically on hematopoietic-derived host cells (Dunn et al., 2005). Collectively, these findings highlight a difference between the antitumor activities of the IFNs, wherein tumor cell responsiveness to IFN-γ but not IFN-α/β and host cell responsiveness to both IFN-γ and IFN-α/β are crucial for tumor rejection. However, the relevant host cell targets and antitumor functions of IFN-α/β and IFN-γ remain undefined because of the nearly ubiquitous expression of IFN-α/β and IFN-γ receptors and the pleiotropic effects they induce.

Although initially defined by their antiviral activity, the type I IFNs are potent immunomodulators that shape host immunity through direct actions on innate and adaptive lymphocytes. The enhancement of NK cell cytotoxicity by IFN-α/β in the setting of viral infection was one of the earliest such effects to be recognized (Biron et al., 1999). Type I IFN directly augments NK cell–mediated killing of virally infected or transformed cells and indirectly promotes the expansion and survival of NK cells through IL-15 induction (Nguyen et al., 2002). Furthermore, in models of NK cell–dependent tumor rejection, host cell responsiveness to IFN-α/β was shown to be important for control of tumor growth and metastasis (Swann et al., 2007). Type I IFN can also act directly on T and B lymphocytes to modulate their activity and/or survival. Treatment with IFN-α/β in vitro prolonged the survival of activated T cells (Marrack et al., 1999) and augmented clonal expansion and effector differentiation of CD8+ T cells (Curtsinger et al., 2005) through cell-intrinsic IFN-α/β receptor signaling. Similarly, type I IFN responsiveness in T cells was required in vivo for optimal clonal expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells during viral infection (Kolumam et al., 2005; Havenar-Daughton et al., 2006; Thompson et al., 2006) as well as for CD8+ T cell priming after immunization with antigen and IFN-α (Le Bon et al., 2006a). B cell differentiation, antibody production, and isotype class switching were also enhanced by type I IFN’s effects either directly on B cells or indirectly via effects on T cells (Coro et al., 2006; Le Bon et al., 2006b) and DCs (Le Bon et al., 2001).

Type I IFN also directly enhances the function of DCs, which are central to the initiation of adaptive immune responses (Steinman and Banchereau, 2007). IFN-α/β induces DC maturation, up-regulates their co-stimulatory activity and enhances their capacity to present or cross-present antigen (Luft et al., 1998; Gallucci et al., 1999; Montoya et al., 2002). For example, coinjection of IFN-α/β plus antigen (Gallucci et al., 1999; Le Bon et al., 2001, 2003) or injection of DC-targeted antigen in combination with the IFN-α/β inducer polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (polyI:C; Longhi et al., 2009) stimulated CD8+ T cell priming, humoral responses, and development of CD4+ Th1 responses in vivo. Recently, a subpopulation of DCs whose development depends on expression of the BATF3 transcription factor (CD8α+ DCs and CD103+ DCs, hereafter referred to as CD8α+ lineage DCs) was shown to play an important role in cross-presenting viral and tumor antigens, and mice lacking these cells fail to reject highly immunogenic unedited sarcomas (Hildner et al., 2008; Edelson et al., 2010). However, it remains unknown whether the cross-presenting activity of these cells requires type I IFN to induce tumor immunity.

In the current study, we have investigated the host cell targets of endogenous type I IFN during the rejection of highly immunogenic, unedited tumors. We demonstrate that IFN-α/β acts early during the initiation of the immune response and that innate immune cells represent the essential responsive cells for the generation of protective antitumor immunity. Whereas type I IFN–unresponsive mice showed a defect in the priming of tumor-specific CTLs, reconstitution of IFN-α/β sensitivity in innate immune cells was sufficient to restore this deficit and resulted in tumor rejection. Within the innate immune compartment, we find no evidence of an essential role for NK cells or for type I IFN sensitivity in granulocytes or macrophages, but rather find that the actions of IFN-α/β on DCs are required for development of tumor immunity in vivo and play an important role in promoting the capacity of CD8α+ lineage DCs to cross-present antigen to CD8+ T cells. These results thus identify DCs and specifically CD8α+ lineage DCs as key cellular targets of type I IFN in the development of protective adaptive immune responses to immunogenic tumors.

RESULTS

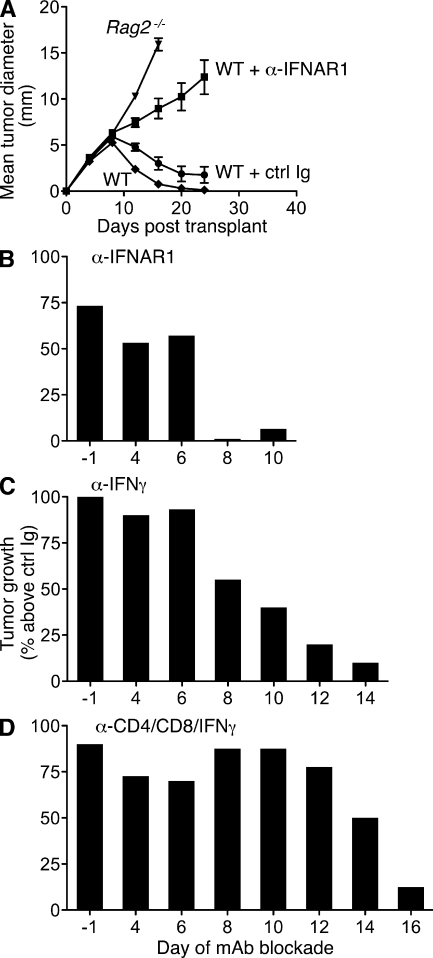

Early requirement for type I IFN during the antitumor response

We previously showed that blockade of type I IFN signaling by pretreatment of mice with the IFNAR1 (IFN-α/β receptor 1)-specific MAR1-5A3 mAb (Sheehan et al., 2006) abrogated rejection of highly immunogenic sarcomas derived from 3′-methylcholanthrene (MCA)–treated Rag2−/− mice (termed unedited tumors; Dunn et al., 2005). To dissect the temporal requirements for IFN-α/β’s actions during the antitumor immune response, we treated WT mice with either MAR1-5A3 or isotype control GIR-208 mAb at different times after injection of unedited H31m1 MCA sarcoma cells. Whereas H31m1 cells were rejected when transplanted into naive syngeneic WT mice either left untreated or pretreated with GIR-208, the tumors grew progressively in WT mice pretreated with MAR1-5A3 (Fig. 1 A). Similarly, MAR1-5A3 treatment on day 4 or 6 (relative to tumor injection at day 0) blocked rejection in >50% of injected mice. In contrast, IFN-α/β receptor blockade at later time points did not inhibit rejection (Fig. 1 B and Fig. S1). In parallel experiments, blockade of IFN-γ via treatment with neutralizing IFN-γ–specific H22 mAb (Schreiber et al., 1985) revealed a more prolonged requirement for the actions of IFN-γ during H31m1 rejection (Fig. 1 C). Cohorts of mice were also treated with a mixture of mAbs that deplete CD4+ and CD8+ cells and neutralize IFN-γ (GK1.5 [Dialynas et al., 1983], YTS169.4 [Cobbold et al., 1984], and H22, respectively) to broadly disrupt host immunity. In this group, progressively growing tumors were observed in a substantial proportion of mice treated as late as day 14 with the anti-CD4/CD8/IFN-γ mAb cocktail (Fig. 1 D). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the obligate functions of type I IFN are required only for initiating the immune response to tumors.

Figure 1.

Early requirement for IFN-α/β during rejection of highly immunogenic tumor cells. (A) Untreated WT and Rag2−/− mice or WT mice injected i.p. with either IFNAR1-specific MAR1-5A3 mAb or isotype control GIR-208 mAb 1 d prior were s.c. injected with 106 H31m1 tumor cells, and tumor size was measured over time. Data represent mean tumor diameter ± SEM of 12–16 mice per group from at least three independent experiments. (B–D) WT mice were injected with 106 H31m1 cells (at day 0) and treated beginning on the indicated day with MAR1-5A3 (B), IFN-γ–specific H22 mAb (C), or a mixture of anti-CD4/anti-CD8/anti–IFN-γ mAbs GK1.5/YTS-169.4/H22 (D), and tumor growth was monitored. For each time point, groups of mice were treated in parallel with the respective isotype-matched control mAb, and the data are presented as percent tumor growth over the control group. Results are from two to four experiments with 14–20 (ctrl/MAR1-5A3), 10–20 (ctrl/H22), or 6–11 (ctrl/cocktail) WT mice per group. The kinetics of tumor growth in individual mice is shown in Fig. S1.

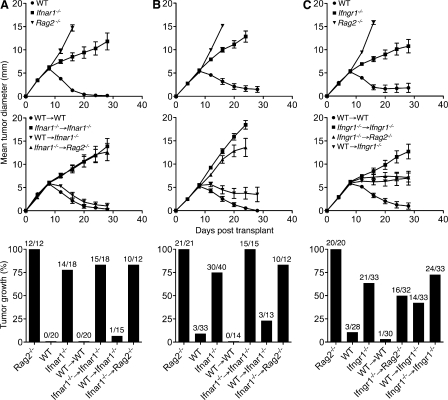

A tissue-restricted role for type I IFN during tumor rejection

To characterize the critical host cells responding to type I IFN during initiation of the antitumor response, we transplanted H31m1 tumor cells and cells from a second unedited MCA sarcoma, d38m2, into bone marrow chimeras with selective IFN-α/β sensitivity. These tumor cell lines were selected because we previously showed that their rejection required type I IFN responsiveness at the level of the host (Dunn et al., 2005). As reported previously, both cell lines were rejected when transplanted into immunocompetent WT mice but formed progressively growing tumors in either Rag2−/− or Ifnar1−/− mice (Fig. 2, A and B). We now show that both lines grew progressively in Ifnar1−/− → Ifnar1−/− bone marrow chimeras and Ifnar1−/− → Rag2−/− chimeras (IFN-α/β sensitivity only in nonhematopoietic cells) but were rejected in WT → WT chimeras and WT → Ifnar1−/− chimeras (IFN-α/β sensitivity only in hematopoietic cells). These results thus extend, to two additional tumors, our prior finding that type I IFN sensitivity within the hematopoietic compartment is both necessary and sufficient for tumor rejection (Dunn et al., 2005).

Figure 2.

Nonoverlapping host cell targets for IFN-α/β and IFN-γ during tumor rejection. (A–C) Control mice and the indicated bone marrow chimeras with selective IFN-α/β sensitivity (A and B) or IFN-γ sensitivity (C) in hematopoietic versus nonhematopoietic cells were injected s.c. with 106 H31m1 (A) or d38m2 (B and C) unedited MCA sarcoma cells, and growth was monitored. Data are presented as mean tumor diameter ± SEM over time or the percentage of tumor-positive mice per group from two to three (A and B) or five (C) independent experiments with group sizes as indicated. Hematopoietic reconstitution of all Ifnar1−/− and Ifngr1−/− bone marrow chimeras was confirmed by flow cytometry at the conclusion of each experiment.

Because the rejection of immunogenic sarcomas also requires IFN-γ sensitivity within the host (Fig. S2), we wanted to determine whether IFN-α/β and IFN-γ were mediating their effects by acting on the same host cell compartment. We thus performed a similar set of experiments using chimeras with selective host cell IFN-γ responsiveness. As expected, d38m2 tumor cells grew progressively in Rag2−/−, Ifngr1−/−, and Ifngr1−/− → Ifngr1−/− mice but were rejected in WT and WT → WT hosts (Fig. 2 C). Tumor growth was also observed in a significant fraction of Ifngr1−/− → Rag2−/− and WT → Ifngr1−/− chimeras, though the defect in these mice (which selectively express the IFN-γ receptor in either nonhematopoietic or hematopoietic cells, respectively) appeared less severe than that in globally insensitive Ifngr1−/− → Ifngr1−/− chimeras. To ensure that tumor growth in the chimeric mice was not caused by incomplete hematopoietic reconstitution, we confirmed normal cellularity and immune cell percentages in the spleen, demonstrated normal functional immune reconstitution, and ruled out the presence of radio-resistant tissue-resident leukocytes within the tumor environment (Figs. S3–S5). These data not only establish an important role for IFN-γ sensitivity in both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells during tumor rejection but also reveal a difference between the broad cellular requirements for IFN-γ as opposed to the tissue-restricted requirement for IFN-α/β during elimination of the same tumor.

Innate immune cells are the critical targets of type I IFN

To examine the role of type I IFN’s actions on innate versus adaptive immune cells, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras with selective type I IFN sensitivity within the hematopoietic compartment. Reconstitution of lethally irradiated Ifnar1−/− mice with a 4:1 mixture of Rag2−/− and Ifnar1−/− hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) yielded mice with IFN-α/β responsiveness solely in innate immune cells (Rag2−/− + Ifnar1−/− → Ifnar1−/− chimeras, hereafter referred to as innate chimeras). Conversely, reconstitution of Ifnar1−/− mice with a 4:1 mixture of Rag2−/− × Ifnar1−/− double KO mice (Rag2−/−Ifnar1−/−) and WT HSCs produced chimeras with IFN-α/β–sensitive T and B lymphocytes but a predominantly IFN-α/β–insensitive innate immune compartment (Rag2−/−Ifnar1−/− + WT → Ifnar1−/−; adaptive chimeras). Control chimeras with responsiveness in both innate and adaptive compartments (Rag2−/− + WT → Ifnar1−/−; innate + adaptive) or neither compartment (Ifnar1−/− → Ifnar1−/−; “neither”) were also generated. The phenotypes of mixed chimeras generated using this approach were confirmed by IFNAR1 staining of splenocyte subsets (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S6).

Figure 3.

IFN-α/β sensitivity within the innate immune compartment is necessary and sufficient for tumor rejection. Mixed bone marrow chimeras with selective IFNAR1 expression in innate or adaptive immune cells were generated by reconstitution of irradiated Ifnar1−/− mice with mixtures of HSCs as described in Results. (A) Splenocytes were isolated from representative cohorts of control and mixed chimeric mice at least 12 wk after reconstitution, and IFNAR1 staining was analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are the percentages of IFNAR1+ cells within the indicated immune cell subsets for 8–14 mice of each type. Horizontal bars represent the mean. (B–D) Control WT, Rag2−/−, and Ifnar1−/− mice and Ifnar1−/− mixed chimeric mice were injected with 106 H31m1 (B), d38m2 (C), or F515 (D) tumor cells, and growth was monitored over time. Data are presented as mean tumor diameter ± SEM or the percentage or tumor-positive mice per group from two to three independent experiments with group sizes as indicated. WT mice treated with control or IFN-γ–specific mAb were challenged with 106 F515 tumor cells, and growth was monitored (D, bottom). Mean tumor diameter ± SEM for 7–10 mice/group from two experiments is shown.

When challenged with H31m1 or d38m2 cells, Rag2−/− and Ifnar1−/− control mice and globally unresponsive “neither” chimeras developed progressively growing tumors. In contrast, WT controls and pan-hematopoietic responsive innate + adaptive or WT → WT chimeras rejected the tumor challenge (Fig. 3, B and C), consistent with our previous results (Fig. 2). Importantly, H31m1 and d38m2 cells were rejected in mixed chimeras with IFN-α/β sensitivity only in innate immune cells (i.e., innate chimeras) but grew progressively in chimeras with IFN-α/β sensitivity largely restricted to the adaptive immune compartment (i.e., adaptive chimeras). These findings demonstrate that the essential antitumor functions of type I IFN on host cells during tumor rejection are selectively directed toward cells of the innate immune compartment.

To confirm the functional hematopoietic reconstitution of Ifnar1−/− mixed chimeras, we performed three experiments. First, we confirmed the normal representation of various immune cell subsets within the spleens of mixed chimeric mice (Fig. 4, A and B). Second, we assessed the in vivo growth behavior of unedited MCA sarcoma cells (F515) that require lymphocytes and IFN-γ but not host IFN-α/β responsiveness for their rejection. F515 tumor cells grew progressively when injected into Rag2−/− mice and WT mice treated with IFN-γ–specific H22 mAb but were rejected in WT mice, WT mice treated with isotype control PIP mAb, and Ifnar1−/− hosts (Fig. 3 D). Similar to Ifnar1−/− mice, F515 cells were also rejected in Ifnar1−/− mixed chimeras of each type, verifying functional reconstitution of the immune compartment. Third, to rule out a potential hyperactive immunological state in these reconstituted mice, we challenged Ifnar1−/− mixed chimeras and control mice with MCA sarcoma cells derived from WT mice (1877). We have previously established that this tumor grows progressively when transplanted into naive WT mice (unpublished data). Similarly, these tumor cells grew progressively in Ifnar1−/− mixed chimeras of each type (Fig. 4 C).

Figure 4.

Normal hematopoietic reconstitution in Ifnar1−/− mixed bone marrow chimeras. (A) Spleens were harvested from WT, Ifnar1−/−, or Ifnar1−/− mixed chimeras of each type (12 wk after reconstitution), and cell density was determined. Horizontal bars represent the mean. (B) Percentages of the indicated immune cell subsets were measured by flow cytometry for WT, Ifnar1−/−, and Ifnar1−/− mixed chimeras. Mean values (as a percentage of total splenocytes) ± SEM for four to five mice/group are shown. Cell populations were defined as follows: CD4+ T cells (CD3+CD4+), CD8+ T cells (CD3+CD8+), B cells (B220+), NK cells (DX5+CD3−), DCs (CD11chi), and myeloid cells (CD11b+). (C) WT-derived 1877 tumor cells were injected at a dose of 106 cells/mouse into WT, Ifnar1−/−, Rag2−/−, and Ifnar1−/− mixed chimeras, and tumor growth was monitored over time. Data represent the mean tumor diameter ± SEM for three to eight mice/group. (A–C) Data are representative of two independent experiments.

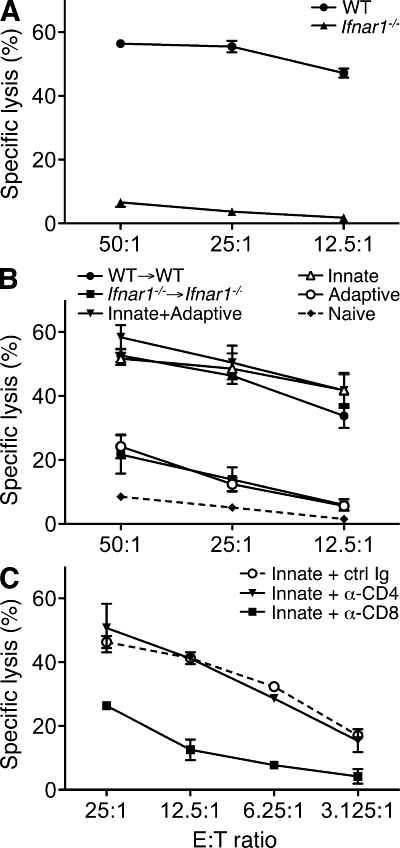

Sensitivity to type I IFN in innate immune cells is required for the generation of tumor-specific CTL

To investigate the mechanism by which endogenous type I IFN promoted host antitumor responses, we looked specifically at the priming of tumor-specific T cells in WT and Ifnar1−/− mice after tumor challenge. Splenocytes from WT hosts isolated 20 d after inoculation of H31m1 tumor cells showed robust cytolytic activity against H31m1 targets after in vitro restimulation (Fig. 5 A). In contrast, tumor-specific killing was largely absent from splenocytes derived from Ifnar1−/− mice challenged with tumor cells. Similar results were observed using another highly immunogenic unedited MCA sarcoma (GAR4.GR1) or using IFN-γ production as a readout (unpublished data). To ask whether type I IFN sensitivity in innate immune cells was sufficient to generate tumor-specific immune responses, we used the mixed bone marrow chimeras described previously (Fig. 3). These experiments showed that IFN-α/β’s actions on the innate immune compartment were indeed both necessary and sufficient for development of tumor-specific cytotoxicity (Fig. 5 B). In addition, treatment of splenocytes from innate chimeras with blocking CD4- or CD8-specific antibodies confirmed the importance of CD8+ cells for in vitro cytotoxicity (Fig. 5 C). These results demonstrate the selective importance of type I IFN on innate immune cells to induce tumor-specific CTL priming.

Figure 5.

Impaired tumor-specific CTL priming in Ifnar1−/− mice is restored by IFN-α/β–responsive innate immune cells. (A) Splenocytes from WT and Ifnar1−/− mice were isolated 20 d after H31m1 tumor challenge (106 cells/mouse), co-cultured with IFN-γ–treated, irradiated H31m1 cells, and 5 d later used as effectors in a cytotoxicity assay with 51Cr-labeled H31m1 targets. Specific killing activity (in percentage ± SEM) at the indicated effector/target (E:T) ratios is shown for four to five mice per group assayed in duplicate from three independent experiments. (B) Splenocytes were harvested from the indicated chimeric mice 20 d after injection of 106 H31m1 tumor cells and were treated as in A. Data include representative results from three mice per group assayed in duplicate from two independent experiments. Splenocytes harvested from a naive mouse and treated similarly served as a negative control. (C) Effector cells from H31m1-challenged innate chimeras were co-cultured at the indicated effector/target ratios with 51Cr-labeled H31m1 targets in the presence of 10 µg/ml control (PIP), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), or anti-CD8 (YTS-169.4) mAbs. Data show representative results from three mice per group assayed in duplicate from three independent experiments. Similar results were obtained when effector cells from H31m1-injected WT mice were used (not depicted). (B and C) Error bars represent SEM.

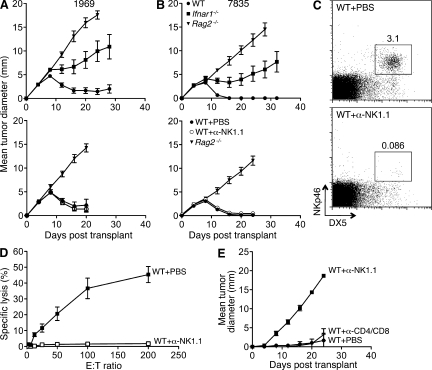

NK cells are not required for type I IFN–dependent tumor rejection

Because NK cells have a host-protective function in some tumor models and display enhanced cytotoxic activity in response to type I IFN, we investigated the role of NK cells in the rejection of highly immunogenic sarcomas. We used comparable unedited MCA sarcoma cells generated from genetically pure C57BL/6 Rag2−/− mice and naive WT C57BL/6 mice as recipients because we could deplete NK cells in C57BL/6 mice with the NK1.1-specific PK136 mAb (Koo and Peppard, 1984). Similar to results with unedited MCA sarcomas from 129/Sv mice, immune-mediated rejection of two representative C57BL/6 strain unedited sarcomas (1969 and 7835) required IFN-α/β sensitivity at the level of the host (Fig. 6, A and B). When PK136-treated WT mice were injected with unedited C57BL/6 tumor cells, they rejected these tumors with kinetics identical to control mice. We confirmed NK cell depletion by (a) flow cytometry, (b) the absence of ex vivo killing of YAC-1 targets by splenocytes from mAb-treated mice, and (c) the lack of in vivo control of RMA-S tumor cell growth (Fig. 6, C–E). These data therefore indicate that NK1.1+ NK cells are not required for IFN-α/β–dependent rejection of unedited MCA sarcomas.

Figure 6.

NK cell depletion does not abrogate IFN-α/β–dependent rejection of immunogenic sarcomas. (A and B) C57BL/6 WT, Rag2−/−, and Ifnar1−/− mice and WT mice treated with either PBS or anti-NK1.1 PK136 mAb were injected s.c. (106 cells/mouse) with 1969 (A) or 7835 (B) unedited MCA sarcoma cells, and growth was monitored over time. Data are presented as mean tumor diameter ± SEM of 4–13 (untreated) or 8 (treated) mice per group from at least two independent experiments. Error bars for Ifnar1−/− mice reflect progressive growth of 1969 and 7835 tumors in 6/9 mice. (C) WT C57BL/6 mice were treated with either PBS or PK136 mAb, and splenocytes were harvested 2 d later and analyzed by flow cytometry using the NK cell markers DX5 and NKp46. Splenocytes were gated on CD3− cells, and the percentages of DX5+NKp46+ cells are indicated. Similar results were found when harvested at day 6 (not depicted). (D) WT C57BL/6 mice were treated with PBS or PK136 followed by i.p. injection of 300 µg polyI:C 4 d later. After 24 h, splenocytes were harvested and used as effectors in a standard 4-h cytotoxicity assay with NK-sensitive YAC-1 targets. Specific lysis (in percentage ± SEM) at the indicated effector/target (E:T) ratios is shown for four mice/group assayed in duplicate from two independent experiments. (E) WT C57BL/6 mice were treated with PBS, PK136, or a mixture of anti-CD4 (GK1.5) and anti-CD8 (YTS-169.4) mAbs and injected s.c. with 105 RMA-S cells, and tumor growth was monitored over time. Mean tumor diameter ± SEM for three mice/group is shown, and data are representative of two independent experiments.

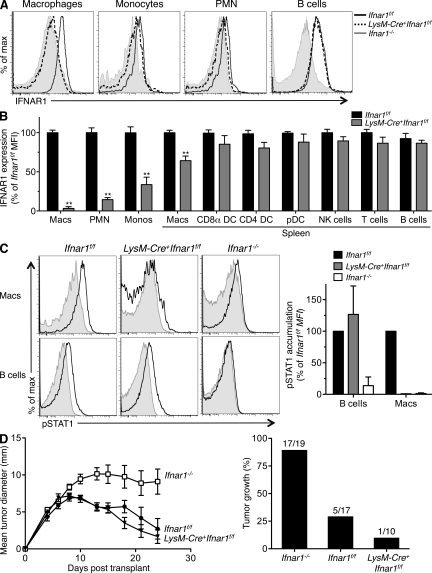

Granulocytes and macrophages do not require type I IFN sensitivity for tumor rejection

To test whether type I IFN sensitivity is required by granulocytes and macrophages for tumor rejection, we crossed C57BL/6 strain LysM-Cre+ mice (Clausen et al., 1999) to C57BL/6 Ifnar1f/f mice (Prinz et al., 2008; prepared by backcrossing 129 strain Ifnar1f/f mice >99% onto a C57BL/6 background using a speed congenic approach). The resulting LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice displayed complete IFNAR1 deletion in peritoneal macrophages and PMNs and substantial deletion of IFNAR1 in monocytes (66%) and splenic macrophages (35%) but maintained undiminished IFNAR1 expression in DCs, NK cells, T cells, and B cells (Fig. 7, A and B). Peritoneal macrophages from these mice were unresponsive to type I IFN and failed to phosphorylate STAT1 after IFN-α stimulation (Fig. 7 C). However, LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice still rejected highly immunogenic unedited B6 strain 1969 sarcoma cells similar to IFN-α/β–responsive Ifnar1f/f mice (Fig. 7 D). In contrast, these tumor cells formed progressively growing tumors in B6 strain Ifnar1−/− control mice. Thus, protective tumor immunity does not require type I IFN sensitivity in granulocytes and at least some macrophage compartments.

Figure 7.

Granulocytes and macrophages do not require type I IFN sensitivity for tumor rejection. (A) IFNAR1 expression on peritoneal macrophages, blood monocytes, PMNs, and B cells was measured using flow cytometry in Ifnar1f/f, LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f, and Ifnar1−/− mice. (B) Summary of IFNAR1 levels in the indicated cellular subsets in LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice compared with Ifnar1f/f mice (expressed as a percentage of the mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]). Cells were gated using the following markers: macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+), PMNs (CD11b+Gr1+), monocytes (CD115+CD11b+), B cells (B220+), CD8α+ DCs (CD8α+Dec205+CD11chi), CD4+ DCs (CD8α−Dec205−CD11chiCD4+), pDCs (B220+PDCA+CD11cint), T cells (CD3+), and NK cells (NK1.1+). IFNAR1 expression was measured using MAR1-5A3 mAb. Data represent at least three mice from three independent experiments (**, P < 0.01). (C) Mature peritoneal macrophages from LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice were untreated (gray) or stimulated for 15 min with 10 ng/ml IFN-αv4 (black), and pSTAT1 accumulation was measured by flow cytometry. Histograms from a representative experiment are shown, with the bar graph summarizing pSTAT1 levels (as percentage of control Ifnar1f/f MFI) from two independent experiments. (B and C) Error bars represent SEM. (D) Ifnar1f/f, LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f, and Ifnar1−/− mice were injected s.c. with 106 1969 unedited sarcoma cells. Mean tumor diameter ± SEM from a representative experiment is shown, and the bar graph shows the percentage of tumor-positive mice per group from two independent experiments with indicated total group sizes.

CD8α+ lineage DCs are important targets of type I IFN’s actions

Having ruled out NK cells, PMNs, and certain macrophage subsets as the critical type I IFN responsive cellular populations, we turned our attention to DCs. We previously showed that the selective absence of CD8α+ lineage DCs in 129 strain Batf3−/− mice led to an impairment in tumor-specific CTL priming and an inability to reject 129 strain H31m1 or 1773 unedited sarcoma cells (Hildner et al., 2008). We subsequently made similar observations using three other unedited 129 strain sarcoma cell lines (d38m2, d42m1, and GAR4.GR1) that require IFNAR1 in host cells for rejection (unpublished data). Given the effects of type I IFN in promoting DC maturation, we hypothesized that DCs, and specifically CD8α+ lineage DCs, may be critical innate immune targets of type I IFN during tumor rejection. The following four sets of experiments were performed to test this hypothesis.

DC subsets develop normally in the absence of IFNAR1.

First, we assessed whether Ifnar1−/− mice displayed a deficiency in any DC populations. Analyses of splenic and LN cells revealed no difference between the numbers of each DC subset in WT and Ifnar1−/− mice (Fig. S7). In addition, there was no defect in the ability of Ifnar1−/− DCs to expand in vivo in response to flt3 (fms-like tyrosine kinase 3) ligand-Fc treatment (not depicted). Thus, the absence of type I IFN signaling did not affect the development of any DC subset.

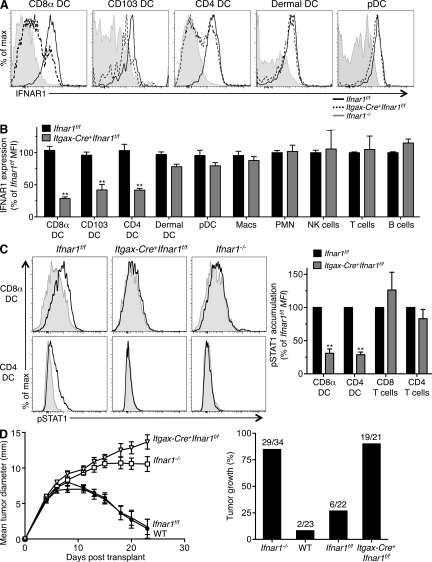

IFN-α/β signaling by DCs is required for rejection of tumors.

Second, we assessed tumor rejection in mice that displayed a selective deletion of IFNAR1 in DCs. We crossed the aforementioned C57BL/6 strain Ifnar1f/f mice to a specific line of Itgax (CD11c)-Cre+ mice generated on a pure C57BL/6 genetic background (Stranges et al., 2007). When compared with the same cell populations from control mice by flow cytometry, IFNAR1 was expressed in undiminished levels in B cells, T cells, NK cells, macrophages, granulocytes, and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) from Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice (Fig. 8, A and B; and Fig. S8 A). In contrast, IFNAR1 expression was substantially reduced in CD8α+ DCs, the highly related CD103+ DCs, and CD4+ DCs from Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice (Fig. 8, A and B). The reduction in IFNAR1 expression corresponds to the selective expression of Cre recombinase in these cell types as indicated by expression of a bicistronic GFP gene that is contributed by the Itgax-Cre mouse (Fig. S8 B). Both CD8α+ and CD4+ DCs from Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice exhibited significantly decreased responsiveness to type I IFN as detected by reduced accumulation of pSTAT1 (Fig. 8 C) and by impaired up-regulation of CD86 upon stimulation with IFN-α (Fig. S8 C). In contrast, T cells and macrophages in Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice displayed type I IFN responsiveness that was comparable with cells from Ifnar1f/f mice. The selective nature of IFNAR1 deletion and loss of function in DCs allowed us to examine whether these cells were obligate targets of type I IFN during development of antitumor responses in vivo. Whereas unedited B6 strain 1969 sarcoma cells were rejected in WT or Ifnar1f/f mice, they formed progressively growing tumors in Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice with growth kinetics indistinguishable from those in Ifnar1−/− mice (Fig. 8 D). These results thus demonstrate that type I IFN sensitivity is specifically required by DCs for development of host-protective tumor immunity.

Figure 8.

DCs specifically require type I IFN sensitivity for tumor immunity in vivo. (A) IFNAR1 expression on splenic CD8α+ DCs, CD4+ DCs, pDCs, LN CD103+ DCs, and dermal DCs was measured using flow cytometry in Ifnar1f/f, Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f, and Ifnar1−/− mice. (B) Summary of IFNAR1 levels on the indicated cellular subsets in Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice compared with Ifnar1f/f mice (expressed as a percentage of control mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]). Cells were gated as follows: CD8α+ DCs (CD8α+Dec205+CD11chi), CD103 DCs (CD8α−Dec205+CD11chiCD103+), CD4+ DCs (CD8α−Dec205−CD11chiCD4+), dermal DCs (CD8α−CD11chiCD103−), pDCs (B220+PDCA+CD11cint), B cells (B220+), T cells (CD3+), NK cells (NK1.1+), macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+), and blood PMNs (CD11b+Gr1+). IFNAR1 expression was measured using the MAR1-5A3 mAb. Data represent three to five mice from at least three independent experiments. (**, P < 0.01). (C) Splenocytes from Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice were untreated (gray) or stimulated for 15 min with 10 ng/ml IFN-αv4 (black), and pSTAT1 accumulation in CD8α+ and CD4+ DCs was measured by flow cytometry. Histograms show a representative experiment, and the bar graph summarizes results from four independent experiments (**, P < 0.01). (B and C) Error bars represent SEM. (D) C57BL/6 WT, Ifnar1−/−, Ifnar1f/f, and Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice were injected s.c. with 106 1969 unedited sarcoma cells. Mean tumor diameter ± SEM from a representative experiment is shown, and the bar graph shows a summary of the percentage of tumor-positive mice per group from three independent experiments with indicated groups sizes (P < 0.001 [WT vs. Ifnar1−/−] and P < 0.001 [Ifnar1f/f vs. Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f]) using the Student’s t test at day 23. Comparisons of Ifnar1−/− versus Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f or WT versus Ifnar1f/f were not significantly different.

Adoptive transfer of type I IFN–responsive DCs into Ifnar1−/− mice promotes induction of antitumor responses.

Third, we examined whether the adoptive transfer of CD11c+ cells isolated from the spleens of naive WT or Ifnar1−/− mice into Ifnar1−/− recipients promoted tumor resistance in vivo. Whereas CD11c+ cells from WT mice induced tumor-specific CTL priming (Fig. S9 A), Ifnar1−/− CD11c+ cells did not. The transfer of WT CD11c+ cells also delayed tumor growth but did not result in tumor rejection (Fig. S9 B). In contrast, no effect on tumor growth was observed upon transfer of CD11c+ cells derived from Ifnar1−/− mice. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.03). These results are consistent with our previous observation that transfer of purified DC populations into Batf3−/− mice results in only partial reconstitution of the antitumor response, perhaps because of issues of DC trafficking (Hildner et al., 2008).

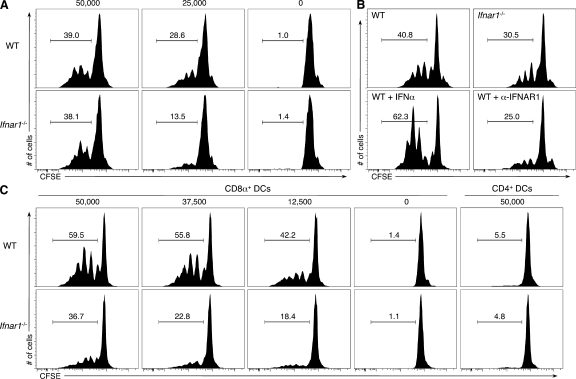

Type I IFN enhances the cross-presenting activity of CD8α+ lineage DCs.

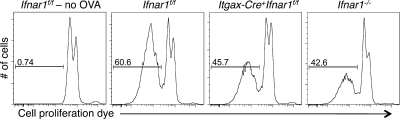

Fourth, we assessed whether type I IFN directly affected antigen cross-presentation by DCs in vitro by culturing splenic DCs isolated from WT or Ifnar1−/− mice with irradiated ovalbumin-loaded MHC class I–deficient splenocytes and OT-I T cells. Total CD11c+ cells purified from WT mice were more effective than Ifnar1−/−-derived cells in inducing the proliferation of OT-I T cells (Fig. 9 A), although this defect could be overcome at high doses of antigen. Cross-presentation by WT CD11c+ cells was enhanced by treatment with exogenous IFN-α and inhibited by the addition of MAR1-5A3 mAb that blocked the type I IFN receptor on these cells (Fig. 9 B). When WT and Ifnar1−/− DCs were further purified into CD8α+ and CD4+ subsets, the CD8α+ DC subset was shown to be the critical cross-presenting cell in this assay, and a more significant deficit was observed in the capacity of Ifnar1−/− CD8α+ DCs to activate OT-I T cells (Fig. 9 C). Importantly, the CD8α+ DCs from Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice displayed an OVA antigen cross-presentation defect that was virtually identical to CD8α+ DCs from Ifnar1−/− mice (Fig. 10). Similar results were also obtained when MHC mismatched, IFN-γ–insensitive CMS-5-ΔIC tumor target cells that were transduced with an OVA-expressing retrovirus were used as a source of antigen (Fig. S10). These findings thus demonstrate that type I IFN acts directly on CD8α+ DCs to enhance cross-presentation of antigen to naive CD8+ T cells.

Figure 9.

Type I IFN sensitivity in CD8α+ DCs enhances antigen cross-presentation. (A) CD11c+ cells were isolated from the spleens of WT or Ifnar1−/− mice and co-cultured with the indicated number of irradiated, ovalbumin-loaded MHC class I−/− splenocytes and CFSE-labeled OT-I T cells. After a 3-d incubation, proliferation of OT-I T cells was determined by CSFE dilution. Histograms represent CFSE levels in the CD8+ T cell population, with the percentage of cells in the indicated gate noted. (B) WT and Ifnar1−/− CD11c+ cells or WT CD11c+ cells incubated with exogenous 1,000 U/ml IFN-α or 5 µg/ml IFNAR1-specific MAR1-5A3 mAb were treated as in A at a dose of 25,000 MHC class I−/− splenocytes. (C) Purified CD8α+ and CD4+ DC subsets isolated from WT or Ifnar1−/− mice were treated as in A with the indicated number of ovalbumin-loaded MHC class I−/− splenocytes. Data represent one of at least two independent experiments with similar results.

Figure 10.

Impaired antigen cross-presentation in CD8α+ DCs from Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice. CD8α+ DCs were isolated from Ifnar1f/f, Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f, and Ifnar1−/− mice and incubated with OT-I T cells labeled with cell proliferation dye and 12,500 ovalbumin-loaded MHC class I−/− splenocytes. Dilution of the cell proliferation dye was measured 3 d later. Data represent one of at least two independent experiments with similar results.

DISCUSSION

Previous work from our laboratory and others has shown that naturally occurring, host-protective immune responses against many highly immunogenic tumors require the obligate participation of endogenously produced type I IFN (Dunn et al., 2005; Swann et al., 2007). Although these earlier studies pointed to hematopoietic cells as the physiologically relevant targets of type I IFN action, they neither identified the specific cell populations affected nor defined the functions that they performed. The current study was undertaken to elucidate the role of endogenously produced type I IFN in driving host-protective, antitumor responses. Herein we demonstrate that type I IFN exerts its activity early during the development of the antitumor response, that its major physiological function is directed selectively toward a single host cell population (i.e., DCs), and that, at least in part, it functions to enhance the capacity of CD8α+ DCs to cross-present antigen to CD8+ T cells. These data thus reveal that the actions of type I IFN during tumor rejection are distinguishable from those of IFN-γ both temporally and functionally, and they represent an important step toward mapping the critical molecular pathways involved in cancer immunoediting.

Functionally active type I IFN receptors are expressed on nearly all nucleated cells, and previous studies documented effects of type I IFN on many immunologically relevant cell types (such as T cells, NK cells, and DCs) that theoretically should enhance the immune elimination of tumors (Dunn et al., 2006). Thus, it was surprising to find an essential functional requirement for type I IFN in only a single cellular compartment, namely DCs, during the development of protective tumor-specific immune responses in vivo. As further documented in vitro, type I IFN enhances the function of the CD8α+ DC subset, which in a previous study was shown to play a critical role in the development of tumor- and virus-specific immune responses through its capacity to cross-present antigen to CD8+ T cells (Hildner et al., 2008). These cells, which are dependent on the BATF3 transcription factor for their development, were originally identified as the CD8α+ DCs that resided in lymphoid organs; yet subsequent work showed that they are closely related to another small DC subset residing in peripheral tissues that lack CD8α but express CD103 (Hildner et al., 2008; Ginhoux et al., 2009; Edelson et al., 2010). Although we find herein that optimal cross-presenting activity of CD8α+ DCs occurs only in response to type I IFN, our results do not exclude a requirement for type I IFN in regulating other DC populations such as CD4+ DCs. Thus, we conclude that the CD8α+ DC subset represents one innate immune cell population that displays an obligate requirement for type I IFN to perform its function in the antitumor response.

Support for this conclusion comes directly from the finding that bone marrow chimeric mice with selective reconstitution of type I IFN sensitivity in the innate immune compartment generated tumor-specific CTL and rejected immunogenic tumor cells, whereas the direct actions of type I IFN on T and B lymphocytes contributed little to the antitumor response. It is important to stress that whereas the results of our analyses clearly show that T cells are not the essential type I IFN–sensitive cellular population, immune elimination of tumors nevertheless requires both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The lack of a requirement for type I IFN responsiveness in T lymphocytes contrasts with results from studies of CD8+ T cell priming and clonal expansion in the settings of viral infection or protein immunization (Kolumam et al., 2005; Le Bon et al., 2006a). Yet, it was noted in these studies that during infection-induced clonal expansion, the relative importance of type I IFN’s actions on CD8+ T cells depended on the specific microbial pathogen used (Thompson et al., 2006), with T cell expansion during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection showing a profound dependence on type I IFN, but less prominent impairments occurring when other viruses were used. In addition, another study reported no change in the generation of antigen-specific CTL in mice lacking the type I IFN receptor in the T cell compartment after immunization with peptide and IC31 (Pilz et al., 2009), an adjuvant based on Toll-like receptor 9 signaling. Given these data, it was suggested that distinct inflammatory environments might evoke expansion of CD8+ T cell subsets that differ in their dependence on type I IFN for survival and function and that such environmental cues may include the levels of type I IFN and other signals that stem from innate cells (Stetson and Medzhitov, 2006; Thompson et al., 2006). Little is known about the magnitude and localization of type I IFN production (and that of other inflammatory cytokines) during immune responses to tumors, and further investigation is warranted.

To further define the target cells within the innate immune compartment affected by type I IFN, we bred Ifnar1f/f mice to LysM-Cre mice, an accepted method of deleting floxed target genes in non-DC myeloid cells (Clausen et al., 1999). The resulting mice exhibited nearly complete deletion of IFNAR1 in peritoneal macrophages and PMNs and reduced levels of IFNAR1 in other myeloid populations including monocytes and splenic macrophages. Nevertheless, targeting myeloid cell IFNAR1 to the levels observed did not compromise antitumor immunity. These findings exclude a prominent role for granulocyte type I IFN sensitivity in our tumor system contrasting with data in the B16 melanoma model, suggesting that direct effects of endogenous IFN-β on tumor-infiltrating neutrophils are responsible for its antitumor functions by suppressing expression of proangiogenic factors (Jablonska et al., 2010). With respect to the contributions of monocyte/macrophage subsets, more work is needed to define whether specific populations contribute to tumor immunity in the MCA sarcoma model, whether they are the same populations targeted in the LysM-Cre mouse, and which functions, if any, are influenced by type I IFN. Others have nonetheless shown that LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice exhibit a clear phenotype during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis despite observing similar partial reductions of IFNAR1 in myeloid populations (Prinz et al., 2008). LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice display undiminished IFNAR1 expression in DCs. Thus, LysM-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice also serve as a control to support the conclusion that IFNAR1 is required predominantly in DCs and that tumor immunity remains intact when IFNAR1 is genetically deleted in non-DC innate immune compartments.

Given the findings that adaptive immune cells, granulocytes, and macrophages function independently of type I IFN and that NK cells do not play an obligate role in our system, we focused our attention on DCs as likely innate immune targets of type I IFN’s actions. Although type I IFN is a strong inducer of DC maturation (Luft et al., 1998; Gallucci et al., 1999; Montoya et al., 2002), the specific role of this cellular subset in the generation of protective antitumor responses has been difficult to establish. Some studies have indeed implicated bone marrow–derived cells in the cross-presentation of tumor-associated antigen (Huang et al., 1994), whereas others have argued that direct priming may additionally be involved (Ochsenbein et al., 2001; Wolkers et al., 2001). Moreover, although the CD8α+ DC subset is particularly adept at antigen cross-presentation, evidence also exists that other non-DC immune subsets as well as nonhematopoietic stromal cells might be capable of cross-presenting exogenous antigen in some circumstances (Ackerman and Cresswell, 2004; Heath et al., 2004; Spiotto et al., 2004).

The generation of mice lacking the transcription factor BATF3 provided a useful mechanism to study DC cross-presentation in vivo because these mice have a cell-intrinsic defect in the development of CD8α+ DCs but normal representation and function of the remaining DC subsets as well as other hematopoietic lineages (Hildner et al., 2008). Highly immunogenic MCA sarcoma cells, which are rejected in WT mice, formed progressively growing tumors in Batf3−/− mice and displayed growth kinetics comparable with those in lymphocyte-deficient Rag2−/− hosts (Hildner et al., 2008), a result which we have corroborated in the current study. In addition, the defect in Batf3−/− mice correlated with a lack of tumor-specific CTL priming (Hildner et al., 2008). These findings therefore demonstrated that cross-priming by CD8α+ lineage DCs is critical for tumor rejection, although they do not address the nature of the innate immune signals necessary for activation, migration, and in vivo function of these cells. The importance of such stimuli is clear because cross-presentation without activation can lead to tolerance rather than immunity (Steinman et al., 2003; Melief, 2008). A better understanding of this process could provide insight into the mechanisms that progressively growing tumors use to escape immune control.

We show in this study that type I IFN enhances the cross-presentation of cell-associated antigen to naive CD8+ T cells via direct actions on CD8α+ lineage DCs. When taken together with data demonstrating that (a) type I IFN promotes tumor-specific CTL priming, (b) type I IFN acts on innate immune cells to mediate its antitumor effects, (c) IFN-α/β–responsive CD11c+ cells partially reconstitute in vivo CTL priming in Ifnar1−/− mice, (d) CD8α+ lineage DCs are required for CTL priming and tumor rejection, and (e) selective deletion of IFNAR1 in DCs abrogates tumor rejection, the collective evidence supports a host-protective function involving direct actions of type I IFN on CD8α+ lineage DCs.

The mechanism responsible for type I IFN’s enhancement of CD8α+ DC cross-priming remains to be determined. Type I IFN may induce multiple effects on the CD8α+ lineage DCs, including the modulation of antigen capture or processing, peptide shuttling and MHC loading, MHC class I and/or co-stimulatory molecule expression, cellular migration, survival, or the induction of secondary cytokines/chemokines. Although current understanding of the cell biology of cross-presentation is incomplete, some data indicate that heightened or altered antigen processing, rather than better antigen capture, underlies the ability of the CD8α+ DCs to efficiently cross-present antigen (Dudziak et al., 2007; Melief, 2008). Interestingly, a recent study suggested that steady-state production of low levels of IFN-β promotes antigen presentation by DCs to both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells via up-regulation of heat shock protein 70, which boosts formation of MHC–peptide complexes (Zietara et al., 2009). Another recent study demonstrated that type I IFN contributes to cross-presentation by enhancing antigen retention and survival of CD8α+ DCs (Lorenzi et al., 2011). Additional mechanisms must be involved because baseline antigen presentation (in the presence of low-level IFN-β) induces cross-tolerance in the absence of DC activation triggered by inflammatory signals such as enhanced type I IFN production (Melief, 2008). The presence of other inflammatory stimuli, which may collaborate with type I IFN to activate CD8α+ DCs, is suggested by detection of residual low-level priming in the absence of type I IFN signaling and the somewhat more robust tumor growth in Batf3−/− mice (lacking CD8α+ DCs) compared with Ifnar1−/− mice (containing normal numbers of type I IFN–unresponsive CD8α+ DCs). The involvement of other inflammatory stimuli and their influence on type I IFN’s effects remain to be investigated.

Exogenous administration of recombinant IFN-α has shown efficacy in the treatment of human cancer patients (Belardelli et al., 2002). However, despite many years of clinical use, surprisingly little is known regarding its mechanism of action in this setting and the reason IFN-α treatment is effective in only a subset of patients. A host immunostimulatory mechanism is likely given the correlation between favorable responses to systemic IFN-α and the appearance of autoimmune sequelae in metastatic melanoma patients (Gogas et al., 2006). Animal studies have also confirmed that type I IFN activity on host cells, rather than actions on the tumor, mediate the protective effect of IFN-α/β administration (Belardelli et al., 2002). Whereas current treatments generally involve systemic injection of high-dose IFN-α, it is possible that more targeted therapy based on a better understanding of the relevant underlying mechanism of action of type I IFN will enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing undesirable side effects.

In summary, the findings made herein reveal that DCs represent the major targets of type I IFN actions during the induction of spontaneous tumor-specific CD8+ T cell responses and that these responses result, at least in part, from an enhanced capacity of CD8α+ DCs to cross-present antigen to CD8+ T cells. These findings provide a strong rationale for future studies aimed at elucidating the precise DC functions that are regulated by type I IFN that ultimately promote development of naturally occurring or therapeutic immune responses to cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

129/SvPas WT mice were purchased from Charles River. 129/SvEv Rag2−/−, C57BL/6 WT, and C57BL/6 Rag2−/− mice were obtained from Taconic. C57BL/6 strain Itgax-Cre+/− (GFP) mice (Stranges et al., 2007) and LysM-Cre+/− mice (Clausen et al., 1999) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. 129/Sv strain Ifnar1−/− and Ifngr1−/− were as described previously (Dunn et al., 2005). Ifnar1f/f mice were as described previously (Kamphuis et al., 2006). Both Ifnar1f/f and Ifnar1−/− mice were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background by speed congenic analysis (>99.7% purity). 129/Sv Rag2−/−Ifnar1−/− mice were generated by intercrossing Rag2−/− and Ifnar1−/− mice. OT-I transgenic mice on a Rag1−/− background were obtained through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Exchange Program, National Institutes of Health (C57BL6-Tg(OT-I)-RAG1tm1Mom 004175; Mombaerts et al., 1992; Hogquist et al., 1994). C57BL/6 MHC class I–deficient Kb−/−Db−/−β2m−/− mice (Lybarger et al., 2003) were a gift from H. Virgin and T. Hansen (Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO). 129/SvEv background Batf3−/− mice have been described previously (Hildner et al., 2008). Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility in accordance with American Association for Laboratory Animal Science guidelines, and all protocols involving laboratory animals were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee (School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis).

Tumor transplantation.

MCA-induced fibrosarcomas were derived from 129/Sv strain Rag2−/− or WT mice and C57BL/6 strain Rag2−/− mice as described previously (Shankaran et al., 2001; Dunn et al., 2005; Koebel et al., 2007). The GAR4 tumor, derived from an MCA-treated 129/Sv Ifngr1−/−Ifnar1−/− mouse, as well as IFNGR1-resconstituted GAR4.GR1 cells and IFNAR1-reconstituted GAR4.AR1 cells have been described previously (Dunn et al., 2005). RMA-S is an MHC class I–deficient variant of the C57BL/6 strain T lymphoma RMA (Kärre et al., 1986). Tumor cells were propagated in vitro and injected s.c. in a volume of 150 µl endotoxin-free PBS into the shaved flanks of recipient mice as described previously (Dunn et al., 2005). Injected cells were >90% viable as assessed by trypan blue exclusion. Tumor size was measured on the indicated days and is presented as the mean of two perpendicular diameters. When calculating percent tumor growth, mice with tumors >6 mm in diameter were considered positive.

Antibody treatment.

For IFN-α/β receptor blockade, mice were injected i.p. with a single 2.5-mg dose of IFNAR1-specific MAR1-5A3 mAb (Sheehan et al., 2006) or GIR-208 isotype control mAb as described previously (Dunn et al., 2005). For IFN-γ neutralization, 750 µg of IFN-γ–specific H22 mAb (Schreiber et al., 1985) or PIP isotype control mAb was injected i.p. followed by a 250-µg dose every 7 d. Broad immunodepletion was achieved by i.p. administration of a mixture of anti-CD4 GK1.5 mAb (Dialynas et al., 1983), anti-CD8 YTS-169.4 mAb (Cobbold et al., 1984), and IFN-γ–specific H22 mAb. For this regimen, an initial dose of 750 µg of each mAb or of the control PIP mAb was followed by 250 µg of each every 7 d as described previously (Koebel et al., 2007). NK cell depletion was achieved in C57BL/6 mice by i.p. injection of 200 µg anti-NK1.1 PK136 mAb (Koo and Peppard, 1984; BioLegend) on days −2, 0, and 2 (relative to tumor injection) and 100 µg every 5 d.

Generation of bone marrow chimeras.

Recipient mice were irradiated with a single dose of 9.5 Gy and reconstituted with donor HSCs isolated from embryonic day (E) 14.5 fetal livers or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–treated adult bone marrow as described previously (Christensen et al., 2004; Dunn et al., 2005). For harvest of fetal liver cells (FLCs), embryos were extracted at E14.5, livers were removed, washed in sterile endotoxin-free PBS, and homogenized through a cell strainer using a syringe plunger. 5-FU–treated bone marrow was isolated 4–5 d after treatment of donor mice with 150 mg/kg 5-FU by i.p. injection. Cells were injected i.v. at a dose of 5 × 106 (FLCs) or 106 (5-FU–treated bone marrow) cells/mouse in 200 µl PBS. Total cell dose was determined by titration of FLCs (Fig. S3) or based on prior data (Dunn et al., 2005). For mixed chimeras, a 4:1 cell ratio was selected based on testing of different mixing ratios (Fig. S6). Animals were maintained on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Hi-Tech Pharmacal) antibiotic water prepared as described previously (Dunn et al., 2005) for 4 wk after irradiation, and tumor transplantation of chimeric mice was performed at least 12 wk after reconstitution. Hematopoietic reconstitution of all animals was verified by FACS staining of splenocytes at the completion of tumor transplantation experiments. Similar experimental results were obtained with mice reconstituted using FLCs or 5-FU–treated bone marrow as donor cells.

Flow cytometry.

Surface staining of single cell suspensions of splenocytes or tumor cells was performed using standard protocols and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (BD). Data analysis was conducted using FlowJo software (Tree Star). The following were obtained from BioLegend: anti-CD3-FITC (145-2C11), anti-CD4-PE (RMA4-5), anti-CD4-APC (GK1.5), anti–CD8α-APC (53-6.7), anti-CD8α-FITC (53-6.7), anti-B220-FITC (RA3-6B2), anti-CD11b-PE (M1/70), anti-CD11b-PerCP-Cy5.5 (and Pe-Cy7; M1/70), anti-DX5-PE (DX5), anti-DX5-APC (DX5), anti–Gr-1–FITC (RB6-8C5), anti-CD45-FITC (30-F11), anti-CD31-PE (MEC13.3), anti-CD24-FITC (M1/69), anti-CD103-PerCp-Cy5.5 (2E7), anti-Dec205-Pe-Cy7 (NLDC-145), anti-F4/80-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BM8), anti-CD11c-APC-Cy7 (N418), and SA-APC. Anti-CD11c-PE (HL3), anti-CD8α-PerCP-Cy5.5 (53–6.7), and anti-IFNGR1-biotin (GR20) were obtained from BD, anti-NKp46-PE (29A1.4) was purchased from eBioscience, and anti-IFNAR1-biotin (MAR1-5A3) was described previously (Sheehan et al., 2006). For pSTAT1 assays, splenocytes were stained for cell surface markers before stimulation with 10 ng/ml IFN-αv4 for 15 min. Cells were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 90% methanol, and stained for pSTAT1 (BD). For CD86 expression, cells were cultured for 18 h with 10 ng/ml IFN-αv4 before staining for cell surface markers and CD86-PE (BD).

Tumor-specific CTL killing assay.

Spleens were harvested from mice 20 d after tumor implantation, and single cell suspensions were prepared by homogenization using frosted glass slides. 4 × 107 splenocytes were cultured with 2 × 106 IFN-γ–treated, irradiated (100 Gy) tumor cells. 5 d later, the cells were harvested and used as CTL effector cells in a standard 4-h 51Cr-release cytotoxicity assay that used tumor cell targets seeded at 10,000 cells/well and pretreated with 100 U/ml IFN-γ for 48 h. For blocking assays, 10 µg/ml anti-CD8 (YTS-169.4), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), or control mAb (PIP) was added to the cell culture of effector and target cells. Percent specific killing was defined as (experimental condition cpm − spontaneous cpm)/(maximal (detergent) cpm − spontaneous cpm) × 100.

NK cell cytotoxicity assay.

Splenocytes were isolated from mice treated with 300 µg polyI:C (Sigma-Aldrich) by i.p. injection 24 h prior and were used as effector cells with 5,000 51Cr-labeled YAC-1 tumor targets. Percent specific killing was assessed after 4-h coincubation. Each sample was assayed in duplicate, and experiments were performed at least twice.

Adoptive transfer of CD11c+ cells.

Splenic CD11c+ cells from naive WT and Ifnar1−/− mice (10 mice/group) were positively selected by MACS (purity >90%) using CD11c microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). 2 × 106 CD11c+ cells were mixed with 2 × 105 unedited MCA sarcoma cells (GAR4.GR1) in endotoxin-free PBS and injected s.c. in a volume of 200 µl into the flanks of Ifnar1−/− mice at day 0. 3 d later, 2 × 106 CD11c+ cells were injected s.c. around the site of tumor implantation.

Antigen cross-presentation assay.

DC cross-presentation of antigen to CD8+ OT-I T cells was assessed as previously described (Hildner et al., 2008). In brief, spleens from naive WT or Ifnar1−/− mice were digested with collagenase B (Roche) and DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich), and cellular subpopulations were isolated by MACS purification (Miltenyi Biotec). Total CD11c+ DCs were obtained by negative selection using B220, Thy1.2, and DX5 microbeads followed by positive selection with CD11c microbeads. CD8α+ DCs were recovered by B220, Thy1.2, DX5, and CD4 negative selection, followed by CD8α positive selection. CD4+ DCs were isolated by B220, Thy1.2, DX5, and CD8α negative selection, followed by CD4 positive selection. In all cases, purity of the population of interest was >97%. Splenocytes from Kb−/−Db−/−β2m−/− mice were prepared in serum-free medium, loaded with 10 mg/ml ovalbumin (EMD) by osmotic shock, and irradiated (13.5 Gy) as described previously (Hildner et al., 2008). OT-I T cells were purified from OT-I/Rag1−/− mice by CD11c and DX5 negative selection followed by positive selection with CD8α microbeads (purity >99%). T cells were fluorescently labeled by incubation with 1 µM CFSE (Sigma-Aldrich) for 9 min at 25°C at a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml. For the assay, 5 × 104 purified DCs were incubated with 5 × 104 CFSE-labeled OT-I T cells in the presence of varying numbers of irradiated, ovalbumin-loaded Kb−/−Db−/−β2m−/− splenocytes. In some assays, the irradiated target cells were mismatched (BALB/c) tumor cells expressing a truncated version of the IFN-γ receptor to render them IFN-γ insensitive and in which ovalbumin was retrovirally enforced (CMS-5-ΔIC). Ovalbumin expression was confirmed by coexpression of GFP by flow cytometry and by Western blot using a mouse antiovalbumin mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). After 3 d, cells were stained with anti-CD8α-APC and CFSE, or cell proliferation dye (eBioscience) dilution was measured by flow cytometry. For IFN-α treatment, recombinant mouse IFN-α5 (a gift from D. Fremont, Washington University in St. Louis) was added at 1,000 U/ml, whereas IFN-α/β receptor blockade was achieved by incubation with 5 µg/ml IFNAR1-specific MAR1-5A3 mAb.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows the kinetics of tumor growth in mice treated with blocking IFNAR1-specific mAb. Fig. S2 demonstrates the importance of host IFN-γ sensitivity for rejection of unedited sarcomas. Fig. S3 presents a titration of FLCs for generation of bone marrow chimeras. Figs. S4 and S5 show the normal functional immune reconstitution of Ifngr1−/− bone marrow chimeras (Fig. S4) and the absence of radio-resistant, tissue-resident leukocytes in the tumors of these mice (Fig. S5). Fig. S6 shows a determination of the HSC mixing ratio used to generate mixed bone marrow chimeras. Fig. S7 shows an analysis of DC subsets in Ifnar1−/− mice. Fig. S8 shows further characterization of the Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice. Fig. S9 shows adoptive transfer experiments of WT and Ifnar1−/− CD11c+ cells into Ifnar1−/− recipient mice. Fig. S10 shows decreased cross-presentation by CD8α+ DCs from Itgax-Cre+Ifnar1f/f mice compared with Ifnar1f/f mice using retrovirally transduced tumor cells as a source of antigen. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20101158/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Tiffany Stephans for excellent technical assistance, to Dr. Emil Unanue for providing flt3 ligand-Fc, and to all members of the Schreiber laboratory for helpful discussions and assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; Midwest Regional Center of Excellence), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease (Rheumatic Disease Core Centers), the Cancer Research Institute, and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research to R.D. Schreiber and from NIAID to K.M. Murphy. M. Kinder is supported by an Irvington Institute Postdoctoral fellowship from the Cancer Research Institute.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- 5-FU

- 5-fluorouracil

- FLC

- fetal liver cell

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- MCA

- 3′-methylcholanthrene

- pDC

- plasmacytoid DC

- polyI:C

- polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

References

- Ackerman A.L., Cresswell P. 2004. Cellular mechanisms governing cross-presentation of exogenous antigens. Nat. Immunol. 5:678–684 10.1038/ni1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardelli F., Ferrantini M., Proietti E., Kirkwood J.M. 2002. Interferon-alpha in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 13:119–134 10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00022-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron C.A., Nguyen K.B., Pien G.C., Cousens L.P., Salazar-Mather T.P. 1999. Natural killer cells in antiviral defense: function and regulation by innate cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:189–220 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J.L., Wright D.E., Wagers A.J., Weissman I.L. 2004. Circulation and chemotaxis of fetal hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2:E75 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen B.E., Burkhardt C., Reith W., Renkawitz R., Förster I. 1999. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 8:265–277 10.1023/A:1008942828960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbold S.P., Jayasuriya A., Nash A., Prospero T.D., Waldmann H. 1984. Therapy with monoclonal antibodies by elimination of T-cell subsets in vivo. Nature. 312:548–551 10.1038/312548a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coro E.S., Chang W.L., Baumgarth N. 2006. Type I IFN receptor signals directly stimulate local B cells early following influenza virus infection. J. Immunol. 176:4343–4351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtsinger J.M., Valenzuela J.O., Agarwal P., Lins D., Mescher M.F. 2005. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J. Immunol. 174:4465–4469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dialynas D.P., Quan Z.S., Wall K.A., Pierres A., Quintáns J., Loken M.R., Pierres M., Fitch F.W. 1983. Characterization of the murine T cell surface molecule, designated L3T4, identified by monoclonal antibody GK1.5: similarity of L3T4 to the human Leu-3/T4 molecule. J. Immunol. 131:2445–2451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dighe A.S., Richards E., Old L.J., Schreiber R.D. 1994. Enhanced in vivo growth and resistance to rejection of tumor cells expressing dominant negative IFN gamma receptors. Immunity. 1:447–456 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90087-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudziak D., Kamphorst A.O., Heidkamp G.F., Buchholz V.R., Trumpfheller C., Yamazaki S., Cheong C., Liu K., Lee H.W., Park C.G., et al. 2007. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 315:107–111 10.1126/science.1136080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G.P., Bruce A.T., Ikeda H., Old L.J., Schreiber R.D. 2002. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat. Immunol. 3:991–998 10.1038/ni1102-991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G.P., Old L.J., Schreiber R.D. 2004. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:329–360 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G.P., Bruce A.T., Sheehan K.C., Shankaran V., Uppaluri R., Bui J.D., Diamond M.S., Koebel C.M., Arthur C., White J.M., Schreiber R.D. 2005. A critical function for type I interferons in cancer immunoediting. Nat. Immunol. 6:722–729 10.1038/ni1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G.P., Koebel C.M., Schreiber R.D. 2006. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6:836–848 10.1038/nri1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelson B.T., Kc W., Juang R., Kohyama M., Benoit L.A., Klekotka P.A., Moon C., Albring J.C., Ise W., Michael D.G., et al. 2010. Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8α+ conventional dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 207:823–836 10.1084/jem.20091627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallucci S., Lolkema M., Matzinger P. 1999. Natural adjuvants: endogenous activators of dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 5:1249–1255 10.1038/15200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F., Liu K., Helft J., Bogunovic M., Greter M., Hashimoto D., Price J., Yin N., Bromberg J., Lira S.A., et al. 2009. The origin and development of nonlymphoid tissue CD103+ DCs. J. Exp. Med. 206:3115–3130 10.1084/jem.20091756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogas H., Ioannovich J., Dafni U., Stavropoulou-Giokas C., Frangia K., Tsoutsos D., Panagiotou P., Polyzos A., Papadopoulos O., Stratigos A., et al. 2006. Prognostic significance of autoimmunity during treatment of melanoma with interferon. N. Engl. J. Med. 354:709–718 10.1056/NEJMoa053007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havenar-Daughton C., Kolumam G.A., Murali-Krishna K. 2006. Cutting Edge: The direct action of type I IFN on CD4 T cells is critical for sustaining clonal expansion in response to a viral but not a bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 176:3315–3319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath W.R., Belz G.T., Behrens G.M., Smith C.M., Forehan S.P., Parish I.A., Davey G.M., Wilson N.S., Carbone F.R., Villadangos J.A. 2004. Cross-presentation, dendritic cell subsets, and the generation of immunity to cellular antigens. Immunol. Rev. 199:9–26 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00142.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildner K., Edelson B.T., Purtha W.E., Diamond M., Matsushita H., Kohyama M., Calderon B., Schraml B.U., Unanue E.R., Diamond M.S., et al. 2008. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 322:1097–1100 10.1126/science.1164206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogquist K.A., Jameson S.C., Heath W.R., Howard J.L., Bevan M.J., Carbone F.R. 1994. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 76:17–27 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A.Y., Golumbek P., Ahmadzadeh M., Jaffee E., Pardoll D., Levitsky H. 1994. Role of bone marrow-derived cells in presenting MHC class I-restricted tumor antigens. Science. 264:961–965 10.1126/science.7513904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonska J., Leschner S., Westphal K., Lienenklaus S., Weiss S. 2010. Neutrophils responsive to endogenous IFN-beta regulate tumor angiogenesis and growth in a mouse tumor model. J. Clin. Invest. 120:1151–1164 10.1172/JCI37223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis E., Junt T., Waibler Z., Forster R., Kalinke U. 2006. Type I interferons directly regulate lymphocyte recirculation and cause transient blood lymphopenia. Blood. 108:3253–3261 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D.H., Shankaran V., Dighe A.S., Stockert E., Aguet M., Old L.J., Schreiber R.D. 1998. Demonstration of an interferon gamma-dependent tumor surveillance system in immunocompetent mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:7556–7561 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärre K., Ljunggren H.G., Piontek G., Kiessling R. 1986. Selective rejection of H-2-deficient lymphoma variants suggests alternative immune defence strategy. Nature. 319:675–678 10.1038/319675a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebel C.M., Vermi W., Swann J.B., Zerafa N., Rodig S.J., Old L.J., Smyth M.J., Schreiber R.D. 2007. Adaptive immunity maintains occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Nature. 450:903–907 10.1038/nature06309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolumam G.A., Thomas S., Thompson L.J., Sprent J., Murali-Krishna K. 2005. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 202:637–650 10.1084/jem.20050821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo G.C., Peppard J.R. 1984. Establishment of monoclonal anti-Nk-1.1 antibody. Hybridoma. 3:301–303 10.1089/hyb.1984.3.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon A., Schiavoni G., D’Agostino G., Gresser I., Belardelli F., Tough D.F. 2001. Type i interferons potently enhance humoral immunity and can promote isotype switching by stimulating dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity. 14:461–470 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00126-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon A., Etchart N., Rossmann C., Ashton M., Hou S., Gewert D., Borrow P., Tough D.F. 2003. Cross-priming of CD8+ T cells stimulated by virus-induced type I interferon. Nat. Immunol. 4:1009–1015 10.1038/ni978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon A., Durand V., Kamphuis E., Thompson C., Bulfone-Paus S., Rossmann C., Kalinke U., Tough D.F. 2006a. Direct stimulation of T cells by type I IFN enhances the CD8+ T cell response during cross-priming. J. Immunol. 176:4682–4689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon A., Thompson C., Kamphuis E., Durand V., Rossmann C., Kalinke U., Tough D.F. 2006b. Cutting edge: enhancement of antibody responses through direct stimulation of B and T cells by type I IFN. J. Immunol. 176:2074–2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhi M.P., Trumpfheller C., Idoyaga J., Caskey M., Matos I., Kluger C., Salazar A.M., Colonna M., Steinman R.M. 2009. Dendritic cells require a systemic type I interferon response to mature and induce CD4+ Th1 immunity with poly IC as adjuvant. J. Exp. Med. 206:1589–1602 10.1084/jem.20090247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzi S., Mattei F., Sistigu A., Bracci L., Spadaro F., Sanchez M., Spada M., Belardelli F., Gabriele L., Schiavoni G. 2011. Type I IFNs control antigen retention and survival of CD8α(+) dendritic cells after uptake of tumor apoptotic cells leading to cross-priming. J. Immunol. 186:5142–5150 10.4049/jimmunol.1004163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft T., Pang K.C., Thomas E., Hertzog P., Hart D.N., Trapani J., Cebon J. 1998. Type I IFNs enhance the terminal differentiation of dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 161:1947–1953 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lybarger L., Wang X., Harris M.R., Virgin H.W., IV, Hansen T.H. 2003. Virus subversion of the MHC class I peptide-loading complex. Immunity. 18:121–130 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00509-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrack P., Kappler J., Mitchell T. 1999. Type I interferons keep activated T cells alive. J. Exp. Med. 189:521–530 10.1084/jem.189.3.521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melief C.J. 2008. Cancer immunotherapy by dendritic cells. Immunity. 29:372–383 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P., Iacomini J., Johnson R.S., Herrup K., Tonegawa S., Papaioannou V.E. 1992. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 68:869–877 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya M., Schiavoni G., Mattei F., Gresser I., Belardelli F., Borrow P., Tough D.F. 2002. Type I interferons produced by dendritic cells promote their phenotypic and functional activation. Blood. 99:3263–3271 10.1182/blood.V99.9.3263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumberg D., Monach P.A., Wanderling S., Philip M., Toledano A.Y., Schreiber R.D., Schreiber H. 1999. CD4(+) T cells eliminate MHC class II-negative cancer cells in vivo by indirect effects of IFN-gamma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:8633–8638 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K.B., Salazar-Mather T.P., Dalod M.Y., Van Deusen J.B., Wei X.Q., Liew F.Y., Caligiuri M.A., Durbin J.E., Biron C.A. 2002. Coordinated and distinct roles for IFN-alpha beta, IL-12, and IL-15 regulation of NK cell responses to viral infection. J. Immunol. 169:4279–4287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsenbein A.F., Sierro S., Odermatt B., Pericin M., Karrer U., Hermans J., Hemmi S., Hengartner H., Zinkernagel R.M. 2001. Roles of tumour localization, second signals and cross priming in cytotoxic T-cell induction. Nature. 411:1058–1064 10.1038/35082583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilz A., Kratky W., Stockinger S., Simma O., Kalinke U., Lingnau K., von Gabain A., Stoiber D., Sexl V., Kolbe T., et al. 2009. Dendritic cells require STAT-1 phosphorylated at its transactivating domain for the induction of peptide-specific CTL. J. Immunol. 183:2286–2293 10.4049/jimmunol.0901383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz M., Schmidt H., Mildner A., Knobeloch K.P., Hanisch U.K., Raasch J., Merkler D., Detje C., Gutcher I., Mages J., et al. 2008. Distinct and nonredundant in vivo functions of IFNAR on myeloid cells limit autoimmunity in the central nervous system. Immunity. 28:675–686 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z., Blankenstein T. 2000. CD4+ T cell—mediated tumor rejection involves inhibition of angiogenesis that is dependent on IFN gamma receptor expression by nonhematopoietic cells. Immunity. 12:677–686 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80218-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z., Schwartzkopff J., Pradera F., Kammertoens T., Seliger B., Pircher H., Blankenstein T. 2003. A critical requirement of interferon gamma-mediated angiostasis for tumor rejection by CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 63:4095–4100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R.D., Hicks L.J., Celada A., Buchmeier N.A., Gray P.W. 1985. Monoclonal antibodies to murine gamma-interferon which differentially modulate macrophage activation and antiviral activity. J. Immunol. 134:1609–1618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R.D., Old L.J., Smyth M.J. 2011. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 331:1565–1570 10.1126/science.1203486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran V., Ikeda H., Bruce A.T., White J.M., Swanson P.E., Old L.J., Schreiber R.D. 2001. IFNgamma and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity. Nature. 410:1107–1111 10.1038/35074122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan K.C., Lai K.S., Dunn G.P., Bruce A.T., Diamond M.S., Heutel J.D., Dungo-Arthur C., Carrero J.A., White J.M., Hertzog P.J., Schreiber R.D. 2006. Blocking monoclonal antibodies specific for mouse IFN-alpha/beta receptor subunit 1 (IFNAR-1) from mice immunized by in vivo hydrodynamic transfection. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 26:804–819 10.1089/jir.2006.26.804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth M.J., Dunn G.P., Schreiber R.D. 2006. Cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting: the roles of immunity in suppressing tumor development and shaping tumor immunogenicity. Adv. Immunol. 90:1–50 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90001-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiotto M.T., Rowley D.A., Schreiber H. 2004. Bystander elimination of antigen loss variants in established tumors. Nat. Med. 10:294–298 10.1038/nm999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R.M., Banchereau J. 2007. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 449:419–426 10.1038/nature06175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R.M., Hawiger D., Nussenzweig M.C. 2003. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:685–711 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson D.B., Medzhitov R. 2006. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity. 25:373–381 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranges P.B., Watson J., Cooper C.J., Choisy-Rossi C.M., Stonebraker A.C., Beighton R.A., Hartig H., Sundberg J.P., Servick S., Kaufmann G., et al. 2007. Elimination of antigen-presenting cells and autoreactive T cells by Fas contributes to prevention of autoimmunity. Immunity. 26:629–641 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street S.E., Cretney E., Smyth M.J. 2001. Perforin and interferon-gamma activities independently control tumor initiation, growth, and metastasis. Blood. 97:192–197 10.1182/blood.V97.1.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street S.E., Trapani J.A., MacGregor D., Smyth M.J. 2002. Suppression of lymphoma and epithelial malignancies effected by interferon gamma. J. Exp. Med. 196:129–134 10.1084/jem.20020063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]