Abstract

This study builds on prior research by Rakow et al. (2009) by examining the role of parental guilt induction in the association between parent depressive symptoms and child internalizing problems in a sample of parents with a history of major depressive disorder. One hundred and two families with 129 children (66 males; Mage = 11.42 years) were studied. The association of parental depressive symptoms with child internalizing problems was accounted for by parental guilt induction, which was assessed by behavioral observations and child report. Implications of the findings for parenting programs are discussed and future research directions are considered.

Keywords: Parental guilt induction, parental depressive symptoms, child internalizing problems

The functional implications of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) are observable not only in individuals diagnosed with this disorder, but also in the children of depressed parents (Goodman, 2007). One process proposed to partially explain the association between parental depression and child outcomes is parenting behaviors (e.g., lack of warmth, psychological control) (for reviews see, Alloy, Abramson, Smith, Gibb, & Neeren, 2006; Goodman, 2007). While parenting has long been found to be associated with child externalizing problems, evidence to support its association with child internalizing problems remains inconsistent (e.g., McLeod, Wood, & Weisz, 2007). Therefore, an important next step in the research process is to identify and examine parenting behaviors more likely to be related to child internalizing symptoms rather than drawing on models that originated from research on parenting and child externalizing problems (see McKee et al., 2008). One particular parenting behavior that has been preliminarily linked with child internalizing problems is psychological control (Barber & Harmon, 2002). However, the specific sub-dimensions of psychological control that may contribute to this association (e.g., attempts to manipulate child behavior via threats of love withdrawal, disapproval, and guilt induction) have received minimal attention.

In line with the recommendations of O’Connor (2002), parenting research examining relations between specific parenting behaviors (e.g., sub-components of psychological control) and specific child outcomes (e.g., internalizing problems) within specific contexts (e.g., parental depression) is needed to increase the level of specificity within the parenting literature. In order to implement this recommendation, it is necessary to dismantle constructs such as psychological control. Within this construct, the subcomponent of parental guilt induction is one that deserves attention, as previous research has found it to be positively related to child internalizing symptoms when used by depressed parents (Rakow et al., 2009).

When used frequently and/or intensely, guilt inducing behaviors - including unwarranted and inappropriate blame and responsibility directed toward the child in combination with declarations of disappointment over minor transgressions- have been associated with child internalizing problems (Donatelli, Bybee, & Buka, 2007; Rakow et al., 2009). Given that depressed parents may lack adaptive parenting skills to manage the behavior of their children (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000) and depressed parents also may reinforce feelings of guilt they instill in their children through continual reminders of the perceived burden of their child (Downey & Coyne, 1990), the association of guilt induction and child internalizing problems is particularly relevant within the context of parental depression (Donatelli et al., 2007).

The current study extends the existing research on parental guilt induction and child internalizing problems (Donatelli et al., 2007, Rakow et al., 2009, Susman et al., 1985) by examining if parental guilt induction operates in the association between current depressive symptoms among parents with a history of depression and child internalizing problems. This study also advances previous research by using a multi-method assessment of parental guilt induction. Specifically, observational data allow for the direct objective assessment of a behavior in a time-limited setting while questionnaires provide less objective data across a broader range of time and settings. When utilized together, the multi-method assessment of parental guilt induction provides the opportunity to comprehensively assess this construct.

Current depressive symptoms of parents with a history of depression were used as the indicator of parental depression as they are related to both parenting (Foster, Garber, & Durlak, 2008) and child internalizing problems (e.g., Abela, Skitch, Adams, & Hankin, 2006) in depressed samples. Both mothers and fathers identified as the target parent were included in the sample as outcomes for children are similar (Kane & Garber, 2004). Finally, both child and parent report were used to assess child internalizing problems.

We tested our hypothesis in a sample similar, but not identical, to the sample used by Rakow et al. (2009), with the addition of observational data. The children were at risk for, but not clinically diagnosed with, depression by virtue of living with a parent with a history of depression. It was hypothesized that parental guilt induction would mediate the account for a significant portion of the association between parental depressive symptoms and child internalizing problems.

Method

Participants

One hundred and two families with 129 children participated. In each family, at least one parent had either current (n=34) and/or past history (n=123) of MDD or current (n=7) and/or past history (n=6) of dysthymia during the lifetime of their child or children. All 9–15-year-old children who met eligibility standards participated. Data were utilized from the baseline assessment of a cognitive-behavioral family-based intervention program designed to prevent mental health problems among the children of parents with a history of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (Compas et al., 2009). The final sample consisted of 90 mothers (Mage = 40.34 years; SD = 7.25), 12 fathers (Mage = 48.92 years; SD = 8.77), and 129 children (66 males) (Mage = 11.44 years; SD = 1.96; range 9–15 years). All parents had full custodial rights of their children throughout participation in the study. Parents were largely Caucasian, non-Hispanic (79.8%), well educated (82.2% reported at least some college), and married or living with a partner (62.8%).

The criterion for inclusion was a parental history of MDD or dysthymia within the child’s lifetime. The criteria for family exclusion were: (a) parental history of bipolar I, or schizophrenia; (b) child history of autism spectrum disorder or mental retardation, bipolar I disorder, or schizophrenia disorder; or (c) child current diagnosis of conduct disorder, substance/alcohol abuse or dependence or depression (see Compas et al., 2009).

Measures

Demographic Information

Demographic variables were reported by the child (child age and gender) and by the parent (parental age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, level of education, and household income).

Parent Depressive Symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), was used to assess current levels of parental depressive symptoms. The BDI-II is a 21-item widely used self-report inventory with excellent reliability and validity data. The alpha coefficient for the current sample was .91.

Parental Guilt Induction

This construct was assessed by two indicators. First, the Maladaptive Guilt Inventory (MGI) (Donatelli et al., 2007) is a 22-item child-completed questionnaire that assesses parental guilt induction by asking children to rate how true each item is on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true) (e.g., “My mom makes me feel guilty about leaving home to do things with other people”).Exploratory factor analysis suggests that the MGI is best conceptualized as a single factor of 12 items (see Rakow et al., 2009), which had an alpha coefficient in the current study of .88. The MGI has been deemed a reliable measure of child-report of parental guilt induction in previous studies of children within a similar age range (see Rakow et al., 2009; Donatelli et al., 2007).

Second, observations of parental guilt induction were assessed via the coding of a 15-minute parent-child videotaped interaction using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scale (IFIRS), a scale with substantial reliability and validity data (Melby & Conger, 2001). The definition of parental use of guilt was the degree to which the parent achieved goals or attempted to control or change the behavior or opinions of the child by means of contingent complaints, manipulation, or revealing needs or wants in a whiny and blaming manner. These expressions convey the sense that the parent’s life is made worse by something the child does (e.g., the message is given that if the child does not behave as requested, the parent will be distress or mistreated). The code captures the parent’s specific guilt inducing behaviors and vocalizations observed during the interaction. Coders rated guilt induction on a 9-point scale with 1 being “not at all characteristic” and 9 being “mainly characteristic” of the parent during the interaction. Coders were trained to weigh the affect, intensity, frequency, duration and proportion of behaviors when determining a rating. When codes were two points apart or more (only 10% of the ratings in this study), coders met to discuss and reconcile discrepancies (Melby & Conger, 2001).

Child Internalizing Problems

The 118-item Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18 (CBCL/6–18; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and Youth Self-Report for Ages 11–18 (YSR/11–18; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) were used to examine child behavior from the perspective of the parent and the child, respectively. The CBCL/6–18 and YSR/11–18, each of which has excellent reliability and validity data, yield two broadband factors, internalizing and externalizing. For the current sample, the alpha coefficient was .90 and .72 for the CBCL-internalizing and eternalizing and .79 and .72 for the YSR-internalizing and externalizing. The YSR was completed by 51 children younger than 11, which is the minimum age for which there is a norm. To ensure the measure had adequate internal consistency for these children, an alpha coefficient was calculated and was .84.

Procedure

After screening (see Compas et al., 2009), a 3 hour assessment occurred in a university setting. The parent-child dyad completed packets of questionnaires in separate rooms and then jointly participated in two 15-minute videotaped interactions. For the first interaction task they discussed a recent activity that their family did together. For the second interaction task they discussed the last time the parent was sad or depressed, including what they each did to try to deal with it. For coding purposes, only the second of the two 15-minute interactions was used. The parent and child were each paid $40 for their time.

Results

Marital status and child gender were significantly related to child internalizing problems and thus controlled for in primary analyses.

A correlation between the Maladaptive Guilt Inventory and the IFIRS parental guilt induction observational code was calculated. Because of the nested nature of the data, correlations were computed after individual cases had been weighted. Previous research has shown that other IFIRS parenting scales are significantly correlated with child report of parenting (e.g., Ge, Best, Conger, & Simons, 1996). Results in the current study yielded a significant correlation (r =.24, p < .05), which approximated the correlations noted in previous research. In line with the methodology of previous research (e.g., Ge et al., 1996) and to take into account both the overlapping and unique contribution of each measure to the construct, the two measures of parental guilt induction were standardized and summed to form a single construct.

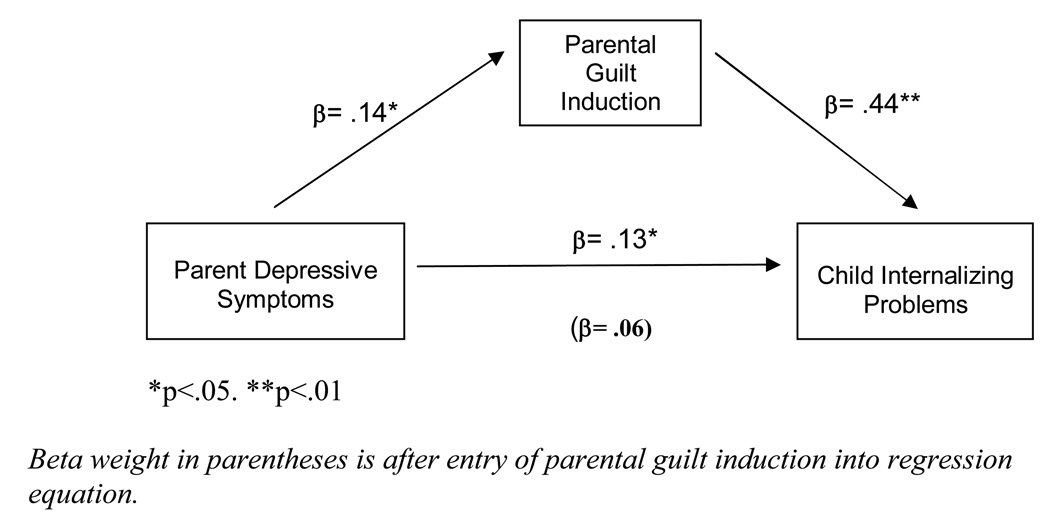

Linear Mixed Models Analyses (LMM) in SPSS was used because multiple children from the same family were included in the analyses. Analyses were initially conducted after combining the child report and behaviorally observed parental guilt induction into a single construct and parent and child report of internalizing problems into a single construct. Baron and Kenny’s (1986) four step process for testing mediation, was followed; however, estimates of mediation are constrained by the cross-sectional nature of the data (Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Higher levels of parental depressive symptoms were related to higher levels of parental guilt induction (β = .14, p ≤ .05), higher levels of parental guilt induction were associated with more child internalizing problems (β = .44, p ≤ .01), and higher levels of parental depressive symptoms were associated with more child internalizing problems (β = .13, p ≤ .05). Parental depressive symptoms, when considered in the context of control variables and parental guilt induction, were no longer significantly associated with child internalizing problems (β = .06, p = .18) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The role of parental guilt induction in the relation of parental depressive symptoms with child internalizing problems.

The relation of each measure of parental guilt induction to parent and child report of child internalizing problems was next examined to assess their relative contribution: The two parental guilt induction measures were simultaneously entered into regression equations. Both behaviorally observed (β = .40, p ≤ .05) and child reported (β = .05, p ≤ .01) parental guilt induction were associated with child report of internalizing problems whereas only child report of parental guilt induction (β = .04, p ≤ .01) was associated with parent report of child internalizing problems. Parent depressive symptoms, when considered in the context of control variables and both child report of parental guilt induction and behaviorally observed parental guilt induction, were no longer significantly associated with either parent report of child internalizing problems (β = .05, p = .07) or child report of child internalizing problems (β = .06, p = .81) served as the outcome.

Two sets of secondary analyses were conducted. First, analyses were repeated using only mothers: The same patterns of findings emerged in the data. Second, analyses were repeated with child externalizing problems serving as the outcome measure to ascertain if findings are restricted to child internalizing problems. As parent depressive symptoms were not associated with child externalizing problems (β = .10, p = .19), further analyses were not conducted.

Discussion

The combined construct of parental guilt induction accounted for the association between parental depressive symptoms and child internalizing problems. The independent contribution of child and observational report of parental guilt induction was dependent upon who served as the informant (child, parent) of child internalizing outcomes. This highlights the importance of how both parental guilt induction and child internalizing problems are measured. The absence of an association between parental depressive symptoms and child externalizing problems precluded examining the role of parental guilt induction in this relationship.

Dix and Meunier (2009) recently delineated a number of hypotheses to account for the relationship between parental depressive symptoms and parenting. Several of these hypotheses could explain the current findings. For example, depressive symptoms may lead a parent to use parenting behaviors that have short term, low effort goals. Specifically, a parent may blame a child for causing her or his distress, manipulate the child by inducing guilt, or convey extreme disappointment in the child. In turn, a child may assume responsibility for his or her parent’s mood, actions, and emotional wellbeing, which interferes with psychosocial development, resulting in internalizing problems. Although the current study is cross-sectional, the findings are consistent with the role of parental guilt induction in partially explaining the association between parental depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms.

Limitations of this study include the following: the cross-sectional nature of the data, which limits conclusions about mediation; the characteristics imposed by the exclusionary criteria; and the predominately Caucasian, adult female, college-educated sample. Strengths of the current study include being the first to examine the role of parental guilt induction in explaining the association between parental depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms and the first to assess parental guilt induction from two different perspectives.

The findings suggest that parental guilt induction is a parenting behavior that can begin to answer the question of why parental depressive symptoms are linked to child internalizing problems. If future research, utilizing longitudinal designs to test mediation, confirms the current findings, efforts to reduce parental guilt induction can be included in family-based prevention and intervention programs for children of parents with a history of depression.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is expressed to the parents and children who participated in this project and to the staff at the University of Vermont and Vanderbilt University who conducted this study. Appreciation also is expressed to Jo-Ann Donatelli and Jane Bybee for consultation on and use of the Maladaptive Guilt-Induction measure, Janet Melby and Rand Conger for consultation on use of the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales for coding parent guilt induction, and Deborah Jones for input on aspects of the data analyses. This research was supported by NIMH grants 5R01MH069928-05, 5R01MH069940-05, and 5F31MH080505-02.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/FAM

References

- Abela KRZ, Skitch SA, Adams P, Hankin BL. The timing of parent and child depression: A hopelessness theory perspective. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:253–263. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Smith JM, Gibb, Brandon E, Neeren AM. Role of parenting and maltreatment histories in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders: Mediation by cognitive vulnerability to depression. Clinical Child Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:23–64. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Harmon EL. Violating the self: Parental psychological control of children and adolescents. In: Barber BK, editor. Intrusive parenting. How psychological control affects children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 15–52. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Forehand R, Keller G, Champion JD, Rakow A, Reeslund KL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a family cognitive-behavioral prevention intervention for children of depressed parents. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology. 2009;77:1007–1020. doi: 10.1037/a0016930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Meunier LN. Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Developmental Review. 2009;29:45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Donatelli JL, Bybee JA, Buka SL. What do mothers make adolescents feel guilty about? Incidents, reactions, and relation to depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:859–875. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depression parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CJE, Garber J, Durlak JA. Current and past maternal depression, maternal interaction behaviors, and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:527–537. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Best KM, Conger RD, Simons RL. Parenting behaviors and the occurrence and co-occurrence of adolescent depressive symptoms and conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:717–731. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH. Depression in mothers. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:107–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children’s psychopathology, and father-child conflict: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Colletti CJM, Rakow A, Jones DJ, Forehand R. Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Weisz JR. Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007-a;27:155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG. Annotation: The ‘effects’ of parenting reconsidered: findings challenges, and applications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:555–572. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakow A, Forehand R, McKee L, Coffelt N, Champion J, Fear J, Compas BE. The relation of parental guilt induction to child internalizing problems when a caregiver has a history of depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009;18:367–377. doi: 10.1007/s10826-008-9239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ, Trickett PK, Iannotti RJ, Hollenbeck BE, Zahn-Waxler C. Child-rearing patterns in depressed, abusive, and normal mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:237–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb03438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]