Abstract

13-cis-retinoic acid (13-cis-RA), is given at completion of cytotoxic therapy to control minimal residual disease in neuroblastoma. We investigated the effect of combining 13-cis-RA with cytotoxic agents employed in neuroblastoma therapy using a panel of 6 neuroblastoma cell lines. The effect of 13-cis-RA on the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, was studied by flow cytometry, cytotoxicity by DIMSCAN, and protein expression by immuoblotting. Pre-treatment and direct combination of 13-cis-RA with etoposide, topotecan, cisplatin, melphalan, or doxorubicin markedly antagonized the cytotoxicity of those agents in 4 out of 6 tested neuroblastoma cell lines, increasing fractional cell survival by 1 to 3 logs. The inhibitory concentration of drugs (IC99) increased from clinically achievable levels to non-achievable levels: > 5-fold (cisplatin) to > 7-fold (etoposide). In SMS-KNCR neuroblastoma cells, 13-cis-RA upregulated expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL RNA and protein, and this was associated with protection from etoposide-mediated apoptosis at the mitochondrial level. A small molecule inhibitor of the Bcl-2 family of proteins (ABT-737) restored mitochondrial membrane potential loss and apoptosis in response to cytotoxic agents in 13-cis-RA treated cells. Prior selection for resistance to RA did not diminish the response to cytotoxic treatment. Thus, combining 13-cis-RA with cytotoxic chemotherapy significantly reduced the cytotoxiciity for neuroblastoma in vitro, mediated at least in part via the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family of proteins.

Keywords: Neuroblastoma, retinoic acid, Bcl-2, antagonism, apoptosis

Introduction

More than 50% of high-risk neuroblastoma patients develop recurrent progressive disease often from progression of minimal residual disease (MRD) remaining after myeloablative therapy (1, 2). An agent that induces differentiation and growth arrest of neuroblastoma in vitro, retinoic acid (1, 3, 4) has been proven clinically active (as 13-cis-retinoic acid) against neuroblastoma MRD, as evidenced by a significant increase in event-free and overall survival (1–3).

Retinoic acid (RA), a natural derivative of Vitamin A, is a transcriptional regulator active in embryonic development, causing changes in cell growth and differentiation (4, 5). Many genes relevant to cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis are regulated by the action of RA including, cyclin D (6), p21 (7), p27 (8), MYCN (9, 10), HOX genes (11) and Bcl-2 (12, 13). RA exists in several interconvertable isomeric forms: all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), 9-cis-retinoic acid, 11-cis-retinoic acid, and 13-cis-retinoic acid (13-cis-RA), with ATRA being the predominant natural form in vivo (14).

Due to its improved activity against neuroblastoma in vitro at clinically achievable concentrations for each agent, and superior pharmacological characteristics (15, 16), 13-cis-RA has been employed in neuroblastoma clinical studies. 13-cis-RA has not produced encouraging results against progressive disease, but given at completion of cytotoxic therapy, it can control MRD, significantly improving event-free survival and overall survival (1, 3, 15), likely due to its ability to induce differentiation and sustained growth arrest of neuroblastoma (10, 17).

In APL, ATRA was most effective when combined directly with cytotoxic chemotherapy (18), perhaps due to the downregulation of Bcl-2 by ATRA (14). Therefore some have advocated direct combination of 13-cis-RA with cytotoxic chemotherapy in neuroblastoma (19). Given the ability of mature neurons to upregulate anti-apoptotic molecules (20) and reports that RA increased Bcl-2 expression in neuroblastoma and antagonized apoptosis in neuroblastoma (12, 13), we hypothesized that 13-cis-RA might antagonize cytotoxic chemotherapy in neuroblastoma cell lines by induction of Bcl-2 family proteins.

Our aim was to determine in the laboratory if 13-cis-RA antagonizes cytotoxic agents used in treating neuroblastoma and whether such antagonism is related to induction of the Bcl-2 family of proteins

Methods

Human neuroblastoma cell lines

The six human neuroblastoma cell lines used in this study were obtained from patients at various stages of disease; phase of therapy at establishment, and MYCN amplification status have been previously described (21) (Supplementary Table 1). None of the patients whose tumors gave rise to the cell lines used in this study had been treated with a retinoid. Two additional cell lines used in our experiments, SMS-LHN 12xRR and SMS-KCNR 12xRR, were selected for RA resistance and exhibit altered MYCN regulation and diminished growth arrest in response to RA (22). The identity of the cell lines was verified by short tandem repeat (STR) loci genotyping (23) using the AmpFlSTR Identifiler PCR Amplification Kit (ABI, Carlsbad, California). SMS-SAN, SMS-KCNR, SMS-LHN, SMS-LHN 12xRR, and SMS-KCNR 12xRR were all cultured in RPMI-1640 (Mediatech, Herdon, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA); CHLA-42, CHLA-79, CHLA-90 were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Mediatech, Herdon, VA) supplemented with 3 mmol/L L-glutamine, insulin, transferrin (5 µg/mL each), 5 ng/mL selenous acid (ITS Culture Supplement, Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA), and 20% FBS (complete medium). Cell lines were cultured at 37°C in humidified atmospheric oxygen and 5% CO2, without antibiotics to facilitate mycoplasma detection. Cells were detached from culture vessels with the use of a modified Puck’s saline A + EDTA (24).

As 13-cis-RA is administered in alternating two-week cycles, and cytotoxic agents are often administered days 1 to 3 of a 21-day cycle, possible concurrent administrations of these two neuroblastoma treatment regiments may involve several days 13-cis-RA treatment prior to the three-week chemo cycle. Thus, most of our studies employed a short 13-cis-RA pre-treatment followed by concurrent treatment with cytotoxic drugs and 13-cis-RA.

Chemicals, drugs, and antibodies

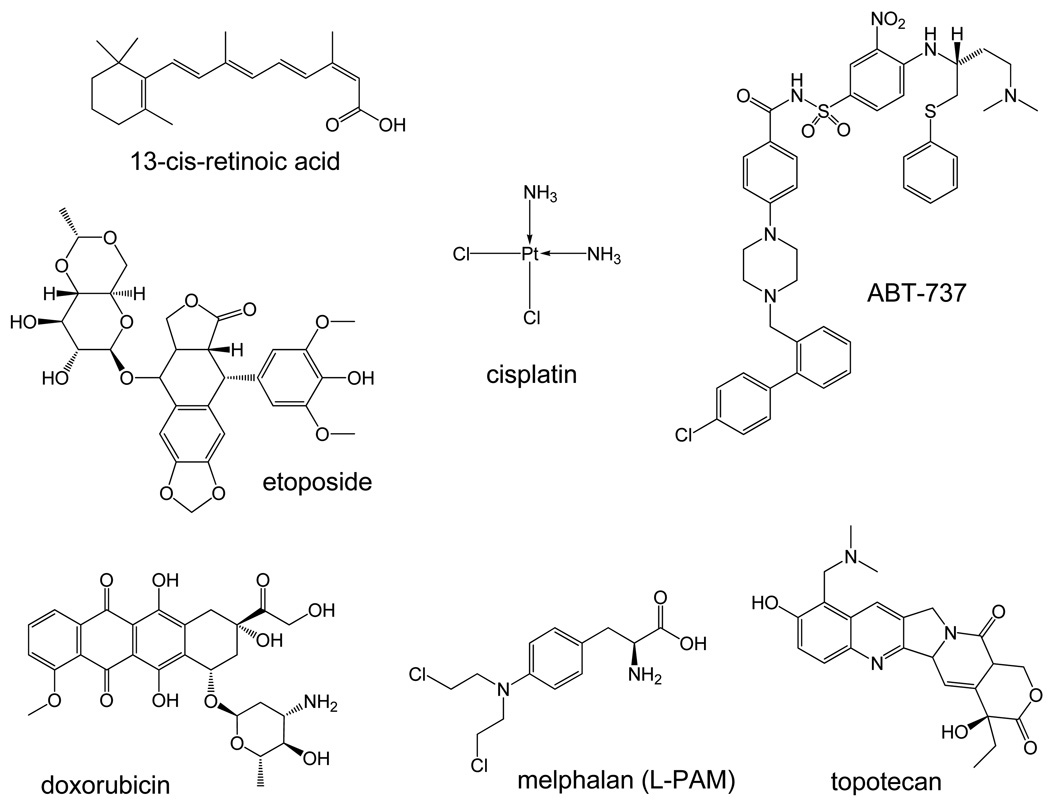

13-cis-RA was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and was dissolved in ethanol. Sytox blue, 5',6,6'-tetrachloro-1,1',3,3'-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1; CBIC2 (3)), and propidium iodide (PI) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fluorescein diacetate was from Eastman Kodak Company (Rochester, NY), and eosin Y was from Sigma Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO). Etoposide (ETOP) was from Bedford Laboratories (Bedford, OH). topotecan (TPT), cisplatin (CDDP), melphalan (L-PAM), and doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) were from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. ABT-737 was kindly provided by Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL) and dissolved in DMSO. Chemical structures of drugs used in this study are shown in Figure 1. All drugs were sterilized by filtration prior to use. Primary antibodies against β-actin, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and cytochrome C and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), antibodies against p53, cytochrome C, and p21 were from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA).

Figure 1. Chemical structures of drugs used in this study.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity assays with ETOP, TPT, CDDP, L-PAM, and DOX as single agents or with 13-cis-RA were performed in 96-well plates using a semi-automated digital image microscopy (DIMSCAN) system (25). A clinically relevant concentration of 5 µM 13-cis-RA (26) and cytotoxic drug concentrations spanning the clinically achievable plasma levels reported for each drug were employed (21, 27–33). The maximum clinically achievable concentrations considered for this study were 5 µg/ml for ETOP, 60 ng/ml for DOX, 0.1 µg/ml for CDDP, 10 µg/ml for L-PAM, and 100 ng/ml for TPT (21, 34).

Depending on doubling time, 5000–15,000 cells were seeded per well, twelve replicate wells for each drug concentration. Cells settled over-night before the addition of 13-cis-RA or ethanol control. Each cytotoxic drug was added 48 hours after RA treatment. Cytotoxicity was measured 7 days after cytotoxic drug was added by incubating with fluorescein diacetate (FDA) (10 µg/mL final concentration) for 20 minutes, followed by 30 µl of eosin-Y (0.5% in normal saline) to quench background fluorescence. Total fluorescence (after digital thresholding) was measured using a DIMSCAN system and results were expressed as the fractional survival of treated cells compared to control cells (25). Statistical differences between cytotoxicity responses to drug single agent and its combination with 13-cis-RA were determined using two-tailed two-sample t-tests. The drug concentrations cytotoxic or inhibiting growth of 99% of cells (IC99), were calculated using the CalcuSyn software (Version 1.1.1 1996, Biosoft, Cambridge, UK).

Quantitiative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocols. Primer and probes were from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and sequences are available online at http://www.COGcell.org/suppdata One step RT-PCR was prepared in 96-well optical reaction plates (ABI, Foster City, CA) and each assay was repeated at least 3 times. Sample wells were prepared with 1x AmpiTaq Gold DNA polymerase mix, 1x RT enzyme mix (Taqman one step RT-PCR master mix, ABI), 400 nM Forward primer, 400 nM Reverse Primer, 200 nM probe, 50 ng total RNA and DEPC-treated water to a total of 25 µl per reaction. An ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems) was employed using 48°C for 30 min, 95°C for 10 min, 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min for a total of 40 cycles. Results were normalized against expression of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) housekeeping gene. Significance was determined using two-sided Student’s T-test in Excel software.

Assessment of mitochondrial potential transition

Unless otherwise stated in figure legends, SMS-KCNR cells were seeded overnight and pretreated with 5 or 10 µM 13-cis-RA or vehicle for 80 hours, followed by treatment with 13-cis-RA or vehicle, 5 µg/ml ETOP and/or ABT-737 (0.125 µM or 1.25 µM) for 16 hours, pelleted, resuspended in 1 mL of Puck’s EDTA containing 10 µg/mL of JC-1, and incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. Dead cells were excluded using 1 µM Sytox blue, a nucleic acid stain emitting at 480 nm that penetrates dead but not live cells (35, 36). JC-1 is a cationic dye that exhibits potential-dependent accumulation in mitochondria, indicated by a fluorescence emission shift from green (525 ± 10 nm) to red (610 ± 10 nm) (37) measured on a BD LSR-II flow cytometer.

Apoptosis

The proportion of cells with sub-G1 DNA content in response to treatment (a generally accepted measure of apoptotic cell death (37)) was assessed using propidium iodide (PI) staining or by TUNEL assay (38). For PI experiments, cells were treated as described earlier in assessing mitochondrial potential transition. Cells were harvested, washed twice, and then fixed in 70% ethanol by slowly adding 700 µl of 100% ice cold EtOH to a 300 µl Pucks EDTA suspension. The samples were rehydrated in PBS, treated with RNAse A, and 50 µg/ml PI. For TUNEL, cells were treated with 10 µM 13-cis-RA for 48 hours, followed by 64 hours of 5 µg/ml ETOP in the presence of 13-cis-RA. Harvested cells were fixed and labeled using the APO-Direct kit (BD Pharmigen, San Jose, CA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. Data were collected with a BD LSR-II flow cytometer using a 488 nm laser and a 610 ± 10 nm (PI) or 525 ± 25 nm (FITC) band pass filters. DNA content was analyzed with ModFit LT 3.0.

Subcellular fractionation

Cytoplasmic fractions for Western blot analysis were isolated using a protocol adapted from Adrian et al 2001 (39); cells were harvested, washed and then permeabilized using a Digitonin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)-based buffer (250 mM sucrose, 70 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.2, 100 100 µM PMSF, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 2 µg/ml aprotinin, containing 200 µg/ml digitonin) on ice for 5 min with occasional light vortexing. Cells were then centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. Supernatants (cytosolic fractions) were saved and used to quantify cytochrome c release by western blotting.

Western blotting

Cell pellets were suspended in 1x RIPA lysis buffer (Upstate, Chicago, IL) containing 1/100x protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) for 20 min on ice. Proteins were fractionated on 4–20 % or 10–20 % Tris-Glycine pre-cast gels (Novex, San Diego, CA), transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Protran, Keene, NH), probed with primary antibodies, then horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and were visualized on film using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Western blots were quantified using Un-Scan-It software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

Results

13-cis-RA antagonized the cytotoxicity of topoisomerase inhibitors, doxorubicin, and alkylating agents

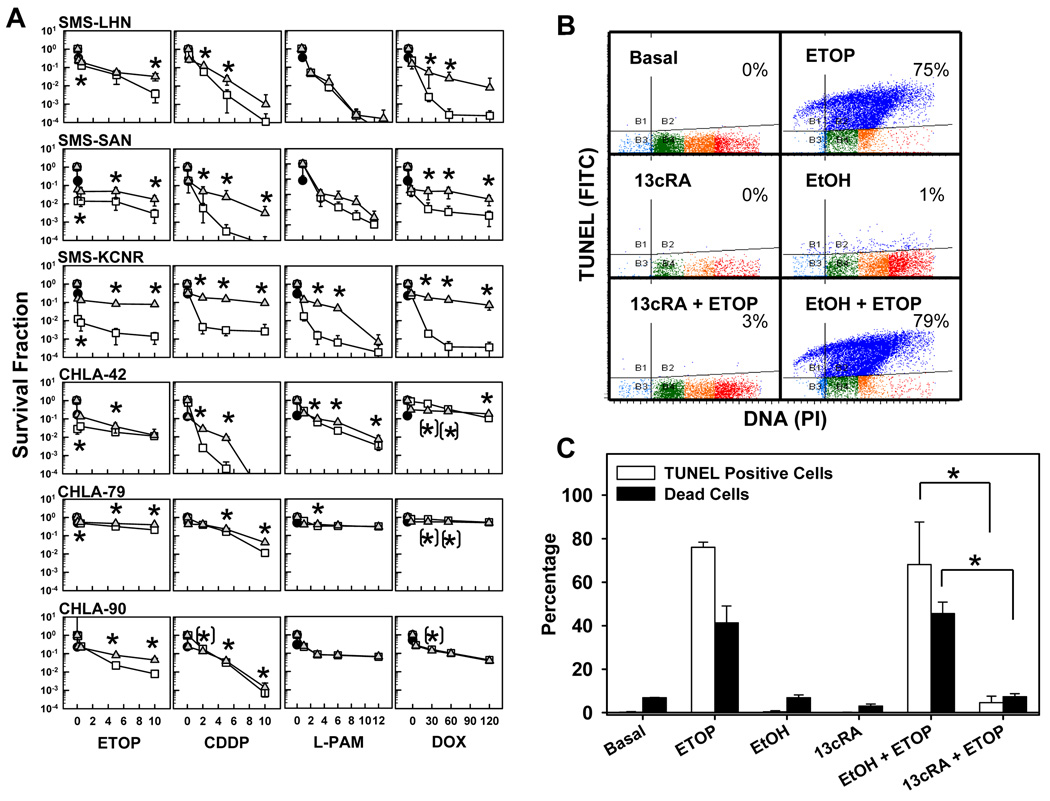

Neuroblastoma cell lines were pretreated with 5 µM 13-cis-RA for 48 hours followed by a seven-day incubation with topoisomerase inhibitors (etoposide, topotecan), alkylating agents (cisplatin, melphalan), or doxorubicin in the presence of absence of 13-cis-RA. Drug concentrations for the cytotoxicity assays spanned the clinically achievable concentration range for each agent. As shown in Fig. 2A, 13-cis-RA induced statistically significant (p<0.05) shifts in most cytotoxicity curves and had a substantial protective effect on SMS-LHN, SMS-SAN, and SMS-KCNR cells for each drug. This was not the case for most drugs with the multidrug resistant lines CHLA-42, CHLA-79, or CHLA-90, likely because these lines already manifested resistance to most of the tested drugs (Table 1). IC99 values (drug concentrations cytotoxic or inhibiting growth for 99% of cells) with or without 13-cis-RA, (Table 1) increased in the presence of 13-cis-RA from clinically achievable to non-achievable concentrations for 4 out of 6 cell lines.

Figure 2. 13-cis-RA pretreatment antagonized the cytotoxicity of etoposide, alkylating agents, or doxorubicin as single agents.

A. Dose-response curves to cytotoxic agents as single agents or in combination with 13-cis-RA. Neuroblastoma cell lines were treated with 13-cis-RA for 48 hours and then exposed to ETOP, CDDP, L-PAM, or DOX for another 7 days. The drug concentrations used were as follows, ETOP (µg/ml) 0.1, 0.5, 5, 10; CDDP (µg/ml) 0.1, 2, 5, 10; L-PAM (µg/ml) 1, 3, 6, 9 and DOX (ng/ml) 5, 30, 60, 120. After a total incubation period of 9 days, cytotoxicity was measured using a DIMSCAN system. Results are expressed as the fractional survival of treated cells compared to control cells after 9 days in 5 µM 13-cis-RA (●), 7 days with the indicated agent ( ), or 2 days in 13-cis-RA followed by 7 days with the indicated agent and 13-cis-RA (

), or 2 days in 13-cis-RA followed by 7 days with the indicated agent and 13-cis-RA ( ). Error bars indicate SD. Significance was defined as (p≤0.05) and significance of the differences between treatments was calculated using two-tailed two-sample t-tests for the three highest drug concentrations. ’*’ indicates statistically significant survival advantage for the combination and ’(*)’ indicates significant advantage for the single agent.

). Error bars indicate SD. Significance was defined as (p≤0.05) and significance of the differences between treatments was calculated using two-tailed two-sample t-tests for the three highest drug concentrations. ’*’ indicates statistically significant survival advantage for the combination and ’(*)’ indicates significant advantage for the single agent.

B. Representative dot plots and corresponding percentages, showing cells undergoing DNA fragmentation, staining positively by TUNEL stain. SMS-KCNR cells were treated with 13-cis-RA and ETOP as described and used for TUNEL staining and flow cytometry. The Y-axis indicates TUNEL staining (using a FITC labeled antibody) and corresponds to the amount of DNA fragmentation. The X-axis indicates DNA content by propidium iodide staining. Quadrant markers were drawn in the cytograms to delineate healthy cells in the lower right, and cells with degraded DNA (sub-G1 DNA content) but little or no DNA fragmentation in the lower left. Cells in the upper left have degraded sub-G1 DNA content and fragmented DNA, and the upper right quadrant contains cells with DNA strand breaks, but without DNA loss. Blue indicates cells with DNA strand breaks, cells with sub-G1 DNA content but without DNA breaks are in turquoise, and healthy cells with G1, S and G2/M DNA content are in green, orange and red respectively.

C. Bar graph indicating average values of TUNEL assay results described above and corresponding sample viability. Open bars illustrate the average frequency of cells with fragmented DNA Vs treatment. Black bars indicate sample viability. Assessment of sample viability was determined by the trypan blue exclusion method and a hemocytometer. Triplicate results from vehicle control + ETOP were compared to those from 13-cis-RA + ETOP using two-tailed Student’s T-test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p≤ 0.05). (13cRA = 13-cis-RA)

Table 1.

Treatment with 13-cis-RA increased the IC99 drug concentrations from clinically achievable to non-achievable levels.

| IC99 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETOP (µg/ml) | DOX (ng/ml) | CDDP (µg/ml) | LPAM (µg/ml) | TOPO (ng/ml) | ||||||

| MCA Concentration |

5 | 60 | 0.1 | 10 | 100 | |||||

| 13-cis-RA | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| SMS-SAN | <1.3 * | >10 | 20.5 | >120 | 0.7 | 7.0 | <1 | 1.6 | <20 | >100 |

| SMS-LHN | 8.5 | >10 | 18.3 | >120 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 2.1 | <20 | >100 |

| SMS-KCNR | <1.3 | >10 | 19 | >120 | 2 | >10 | 1.3 | 6.3 | 94 | >100 |

| CHLA-42 | >10 | >10 | >120 | >120 | 7.8 | >10 | 7.7 | >12 | N/D | N/D |

| CHLA-79 | >10 | >10 | >120 | >120 | >10 | >10 | >12 | >12 | N/D | N/D |

| CHLA-90 | 7.9 | >10 | >120 | >120 | 5.5 | 8.2 | >12 | >12 | N/D | N/D |

< or > indicates IC99 concentrations lower or higher than the lowest or highest concentration tested. All numbers are rounded to the first decimal point.

MCA = Maximum Clinically Achievable.

Some of the statistically significant changes observed in the survival plots would likely not result be clinically significant since they did not result in meaningful IC99 value changes. For example, the CHLA-79 response to DOX single agent was calculated to have a significant advantage over the combination at 30 and 60 ng/ml but this is not meaningful as both treatments have an IC99 higher than the clinically achievable concentration. The protective effect of 13-cis-RA was most dramatic with SMS-KCNR cells, where 13-cis-RA treatment increased IC99 values > 5-fold for CDDP, > 6-fold for DOX, and > 7-fold for ETOP. SMS-LHN, SMS-SAN, and SMS-KCNR cell lines were also tested against TPT (20, 40, 80, 100 (ng/ml)), giving results similar to those obtained with ETOP (data not shown). A direct combination of ETOP with 13-cis-RA (without 13-cis-RA pre-treatment) in SMS-KCNR cells also antagonized the cytotoxic effect of ETOP (supplementary Fig. 1).

13-cis-RA decreased etoposide-induced apoptosis

We chose the SMS-KCNR cell line and the antagonism by 13-cis-RA of ETOP cytotoxicity for investigating the molecular mechanism(s) involved in this antagonistic interaction. As ETOP is cytotoxic via the p53 and mitochondrial apoptotic pathways (40), we evaluated perturbation of apoptotic events by 13-cis-RA (Fig. 2 B,C). Apoptosis (TUNEL assay) in response to ETOP was present in 68% of the cell population (basal 0.5%) while 13-cis-RA protected SMS-KCNR cells from etoposide and decreased apoptosis to 4.5%. Cell viability was measured using a hemocytometer and trypan blue exclusion (Fig. 2C), and the cell viability results were consistent with the TUNEL data.

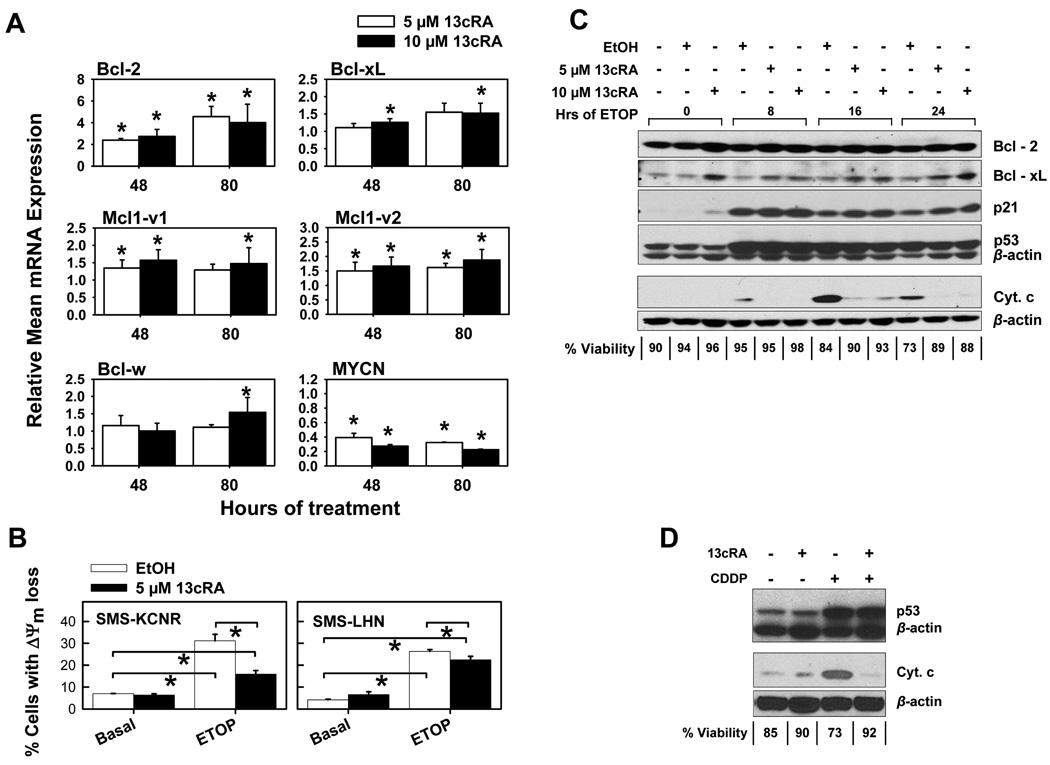

13-cis-RA treatment increased mRNA expression and protein levels of anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, and protected against etoposide-mediated mitochondrial depolarization

As ATRA has been shown to upregulate Bcl-2 expression in neuroblastoma cell lines (13), we determined if Bcl-2 upregulation occurred with 13-cis-RA. SMS-KCNR cells were treated with 13-cis-RA, and mRNA expression of Bcl-2 family members, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bcl-w, MCL1-v1 and MCL1-v2 was measured by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 3A), while protein levels for Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL were measured by western blotting (Fig. 3C). Average mRNA expression for target genes was normalized to that of the GAPDH housekeeping gene. Downregulation of MYCN mRNA in response to 13-cis-RA has been observed previously (22), and was used as an indicator of molecular responsiveness to 13-cis-RA.

Figure 3. 13-cis-RA treatment altered the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and protected neuroblastoma cells from inner mitochondrial membrane potential loss and cytochrome C release.

A. Effects of 13-cis-RA on mRNA expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. SMS-KCNR cells were treated with 13-cis-RA, and total RNA was used as a template for real time RT-PCR using intron-spanning PCR primer-probe sets for the genes indicated. At least three independent assays were conducted for each RNA sample. Results from replicate wells in each assay were averaged, and normalized by GAPDH expression, and by the expression in EtOH controls to determine a normalized expression value. Normalized values from different assays were then averaged to determine the relative mean mRNA expression. The error bars shown indicate the standard deviation of the normalized expression values. Two-tailed Student’s T-tests were used to compare the sets of normalized expression values for each treatment to those of the EtOH control (relative mean expression equal to 1). Asterisks indicate significant (p< 0.05) differences from the EtOH control (13cRA = 13-cis-RA).

B. Cells were pre-treated with 5 µM 13-cis-RA or EtOH vehicle, followed by a 16-hour treatment with 5 µg/ml ETOP; treated cells were stained with JC-1 dye and analyzed by flow. Sytox blue counterstain was not used. The bar graphs show mean percentage of cells exhibiting mitochondrial membrane potential loss, by treatment. Cell line name is indicated inside each graph. 13-cis-RA reduced the percent of cells with ΔΨm loss from 26% to 22% (basal 4%) in SMS-LHN and from 31% to 16% (basal 7%) in SMS-KCNR cells. Triplicates from each treatment were compared using two-sided Student’s T-tests. Asterisks indicate significant (p≤0.05) differences.

C. Western blotting illustrating the effects of 13-cis-RA treatment on anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein levels, p53 pathway activation, and cytochrome C release in response to etoposide. SMS-KCNR cells were pretreated with 13-cis-RA for 48 hours, and then treated with 5 µg/ml etoposide for the indicated number of hours, in the presence of 13-cis-RA. Ethanol was used as vehicle control. Detection of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, p53 activation and p21 was performed using whole cell lysates. Cytochrome C release was detected in cytoplasmic fractions extracted as described. Percent sample viabilities, by trypan blue exclusion, are indicated below the blot.

D. Western blotting showing a lack of effect of 13-cis-RA treatment on p53 pathway activation and the effect on cytochrome C release from the mitochondria in response to cisplatin. SMS-KCNR cells were pretreated with 10 µM 13-cis-RA for 48 hours; they were then treated with 1 µg/ml CDDP for 24 hours in the presence of 13-cis-RA (control samples with 13-cis-RA or vehicle were treated for a total of 72 hours). Accumulation of p53 was detected in whole cell lysates. The cytoplasmic fraction was extracted as described, and was used to assay for cytochrome C release. Percent sample viabilities, by trypan blue exclusion, are indicated below the graph.

The mRNA expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl1-v1, and Mcl1-v2 was significantly (P ≤ 0.05) increased after 48 or 80 hours of 13-cis-RA treatment. RT-PCR data for Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression were confirmed at the protein level by Western blot in cells treated with 13-cis-RA for 72 hours. These two proteins were also found to be highly expressed when cells were subsequently treated with 5 µg/ml ETOP in the presence of 13-cis-RA (Fig. 3C), although Bcl-xL upregulation was both more consistent and pronounced.

Increased Bcl-2 family expression was associated with protection against ETOP-mediated inner mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) loss as indicated by JC-1 flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 3B). A 48-hour pre-treatment with 5 µM 13-cis-RA reduced the percent cells with ΔΨm loss in response to ETOP from 26% to 22% (basal 4%) in SMS-LHN and from 31% to 16% (basal 7%) in SMS-KCNR cells.

Cells pretreated with 13-cis-RA activated the p53 pathway in response to etoposide or cisplatin but did not release cytochrome C from the mitochondria

We evaluated p53 pathway activation and mitochondrial cytochrome C release in response to ETOP or CDDP. 13-cis-RA did not affect p53 activation in response to either drug, as indicated by p53 levels and p21 accumulation (Fig. 3C, D, and Supplementary Fig. 2, 3). However, 13-cis-RA inhibited cytochrome C release in response to both ETOP and CDDP. Cell viability (trypan blue exclusion) inversely correlated with cytochrome C release.

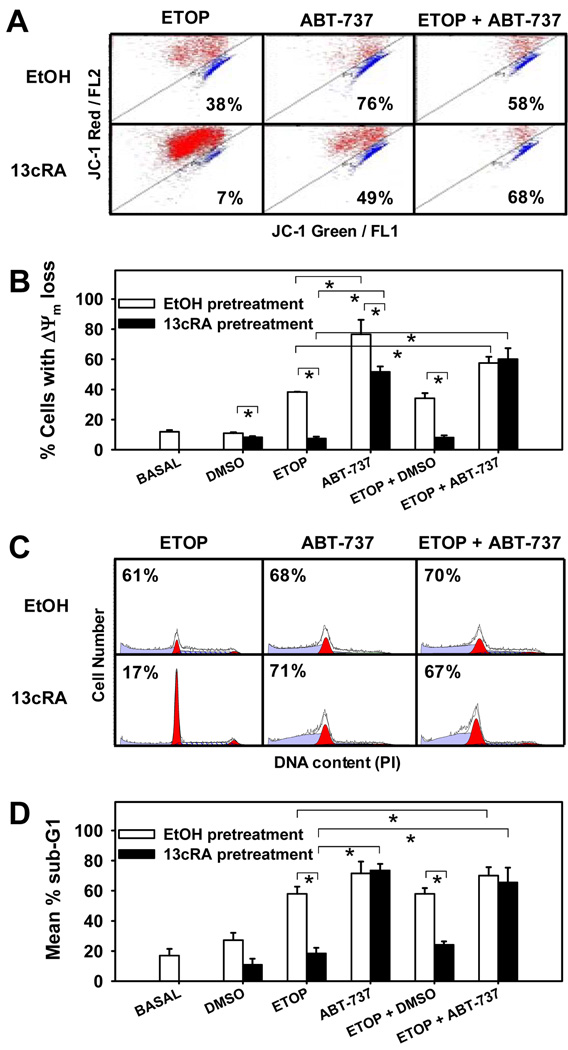

The protective effect of 13-cis-RA is lost when cells were treated with the Bcl-2 family inhibitor ABT-737

Given that 13-cis-RA inhibits ΔΨm loss in response to etoposide (Fig 3B), we determined if the effect was reversible by the small-molecule Bcl-2 family inhibitor ABT-737. SMS-KCNR cells were treated with 10 µM 13-cis-RA for 80 hours (to maximally stimulate the cells), incubated for 16 hours with ETOP and/or ABT-737 in the presence or absence of 13-cis-RA, stained with JC-1, and analyzed by flow cytometry. 13-cis-RA decreased the percentage of cells exhibiting mitochondrial depolarization in response to ETOP from 38% to 8% (basal level = 12%), but 1.25 µM ABT-737 restored it to 52% (Fig. 4A, B). Similar responses were noted with 0.125 µM ABT-737 (data not shown). To exclude the possibility that 13-cis-RA mediates additional apoptotic blocks downstream of the mitochondria, we also measured the accumulation of cells with sub-G1 DNA content in aliquots of the above samples (Fig. 4C, D). 13-cis-RA decreased apoptotic (sub-G1) cells in response to ETOP from 58% to 18% (basal 17%), whereas ABT-737 treatment reversed the antagonistic effect of 13-cis-RA, resulting in 74% apoptosis. These findings suggest that 13-cis-RA antagonized apoptotic cell death via the mitochondrial pathway.

Figure 4. Antagonism of mitochondrial membrane depolarization and apoptosis in response to etoposide by 13-cis-RA and its reversal by ABT-737.

SMS-KCNR cells were treated as described and sample aliquots were used to detect loss of inner mitochondrial membrane potential or accumulation of Sub G1 cells; ABT-737 concentration =1.25 µM.

A. Representative cytograms of JC-1 staining showing loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. Cells with healthy mitochondrial membrane (red) are located above the diagonal line while cells experiencing mitochondrial depolarization (blue) are below the diagonal. Percentages indicate the frequency of cells with depolarized mitochondria for each particular dot plot. Dead cells were excluded by sytox blue staining. Basal, DMSO vehicle, and ETOP treated controls are not shown, these controls gave an average of 12%, 11%, and 30% cells with depolarized mitochondria, respectively.

B. Mean percentage of cells exhibiting mitochondrial membrane depolarization, by treatment. Triplicates for each treatment were compared using two-sided Student’s T-tests. Asterisks indicate significant (p<0.05) differences. No significant difference was observed between ABT-737 single agent to etoposide in combination with ABT-737 (ΔΨm is used as an abbreviation for inner mitochondrial membrane potential.).

C. Representative histograms of DNA content using propidium iodide and flow cytometry, for aliquots from samples used for the JC-1 assay. Data were analyzed using Modfit software and percentages indicate the frequency of cells with sub-G1 DNA content for each particular histogram. Basal, DMSO vehicle and ETOP treated controls are not shown, these gave an average of 17%, 27% and 72% cells with sub-G1 DNA content respectively.

D. Mean percentage sub-G1 cells vs treatment. Asterisks indicate significant (p<0.05) differences. Triplicates from each treatment were averaged and used to compare between treatments. There was no significant difference between ABT-737 single agent and ABT-737 with ETOP.

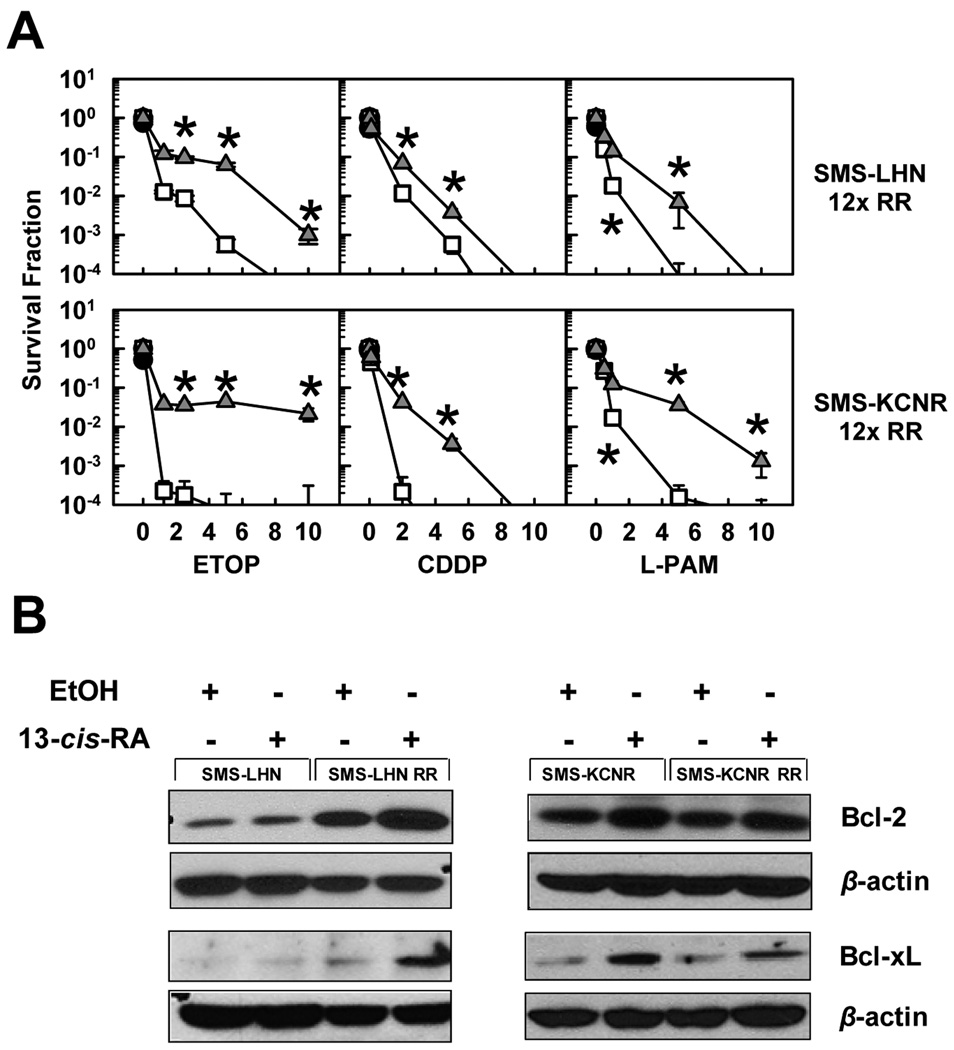

13-cis-RA protected retinoic acid-resistant cell lines from cytotoxic agents

We determined if neuroblastoma cells selected for RA resistance (22) differ in their response to cytotoxic treatment in the presence or absence of 13-cis-RA by conducting DIMSCAN cytotoxicity assays with SMS-LHN 12xRR and SMS-KCNR 12xRR cells. Cells were treated with 5 µM 13-cis-RA for 48 hours followed by a 7-day treatment with ETOP, CDDP, or L-PAM in the presence of 13-cis-RA. Cell survival was significantly (p<0.05) increased when treatment included 13-cis-RA (Fig. 5A). This protective effect was also associated with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL protein upregulation, following treatment with 5 µM 13-cis-RA (Fig. 5B, and supplementary Fig. 4). It should be noted that SMS-LHN 12xRR, which showed greater increase in Bcl-2, Bcl-xL protein expression than the parental cells, also showed a greater shift in cytotoxicity curves in response to RA (Fig. 2A, 4).

Figure 5. 13-cis-RA protects RA-resistant cell lines from etoposide, cisplatin, or melphalan as single agents; the effect correlates with upregulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL.

A. Dose-response curves in response to cytotoxic agents as single agents or in combination with 13-cis-RA. Neuroblastoma cell lines selected for RA resistance were treated with 13-cis-RA for 48 hours and then exposed to one of ETOP, CDDP, or L-PAM for an additional 7 days. The drug concentrations used were, ETOP (µg/ml) 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10; CDDP (µg/ml) 0.1, 2, 5, 10 and L-PAM (µg/ml) 1, 3, 6, 9. After a total incubation period of 9 days, cytotoxicity was measured using a DIMSCAN system. Results are expressed as the fractional survival of treated cells compared to untreated controls after 9 days in 5 µM 13-cis-RA (●), 7 days with the indicated agent ( ), or 2 days in 13-cis-RA followed by 7 days with the indicated agent and 13-cis-RA (

), or 2 days in 13-cis-RA followed by 7 days with the indicated agent and 13-cis-RA ( ). Error bars indicate SD. We used two-tailed t-tests to determine significant (p<0.05) differences between responses for the three highest drug concentrations with or without 13-cis-RA. Asterisks indicate significant differences between treatments.

). Error bars indicate SD. We used two-tailed t-tests to determine significant (p<0.05) differences between responses for the three highest drug concentrations with or without 13-cis-RA. Asterisks indicate significant differences between treatments.

B. Cells were treated with 5 µM 13-cis-RA for 72 hours; whole cell lysates where used to detect Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL by Western blotting. Cell line names are indicated above the blots.

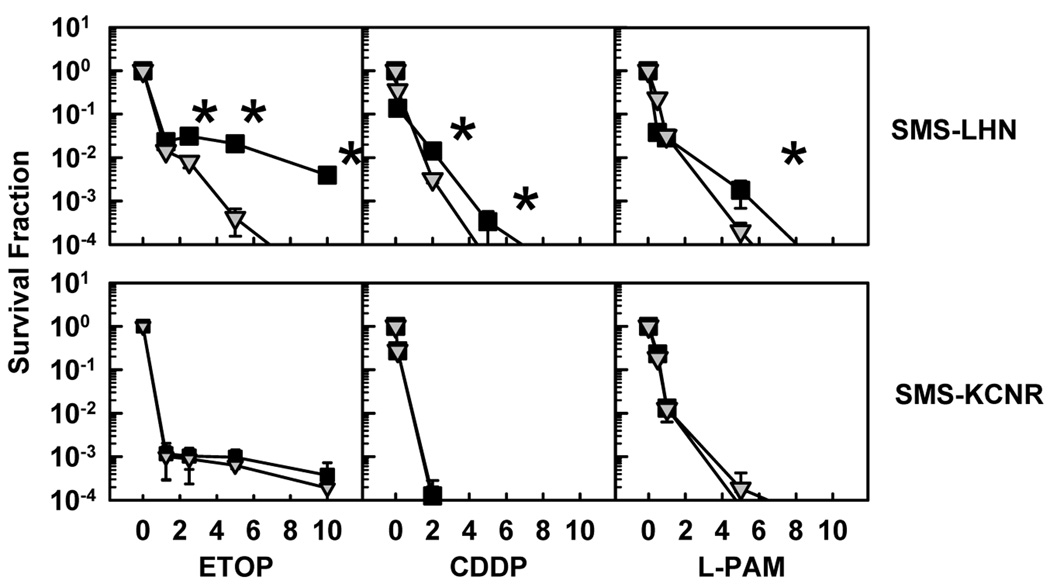

Resistance to 13-cis-RA did not induce resistance to etoposide, cisplatin or melphalan

To determine if prior retinoic acid treatment provided a sustained protection against subsequent treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapy, we compared cytotoxicity of ETOP, CDDP, or L-PAM for SMS-LHN and SMS-KCNR vs cell line variants selected for retinoic acid resistance (SMS-LHN 12xRR and SMS-KCNR 12xRR) (Fig. 6). Neuroblastoma cells selected for resistance to retinoic acid did not manifest cross-resistance to any of the cytotoxic agents tested. Moreover, for SMS-LHN cells, resistance to retinoic acid resulted in a collateral, statistically significant (p<0.05), increase in sensitivity to the agents tested.

Figure 6. Resistance to RA does not protect against etoposide, cisplatin, or melphalan cytotoxicity.

SMS-LHN and SMS-KCNR cell lines and the corresponding cell lines selected for retinoic acid resistance (SMS-LHN 12xRR, SMS-KCNR 12xRR) were treated with ETOP, CDDP, or L-PAM for 7 days. The drug concentrations used were, ETOP (µg/ml) 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10; CDDP (µg/ml) 0.1, 2, 5, 10 and L-PAM (µg/ml) 1, 3, 6, 9. Cytotoxicity was measured using a DIMSCAN system. Results are expressed as the fractional survival of treated cells compared to control cells. Parental cell lines are indicated by ( ) and RA-resistant cell lines are indicated by (■).Error bars indicate SD. Two-tailed t-tests were used to determine significant (p<0.05) differences between plots for the three highest drug concentrations. Asterisks indicate significant differences between responses.

) and RA-resistant cell lines are indicated by (■).Error bars indicate SD. Two-tailed t-tests were used to determine significant (p<0.05) differences between plots for the three highest drug concentrations. Asterisks indicate significant differences between responses.

Discussion

Improved survival of high-risk neuroblastoma, with 13-cis-RA treatment (1, 3, 15), has raised the question of whether combining 13-cis-RA with cytotoxic chemotherapy would be beneficial. Our present study addresses this highly relevant question. Using the DIMSCAN cytotoxicity assay we were able to show that after a pre-treatment with 13-cis-RA, concomitant exposure to 13-cis-RA significantly antagonized the cytotoxicity of ETOP, TPT, CDDP, L-PAM, or DOX, and adversely affected IC99 values in 4 of 6 tested neuroblastoma cell lines. This same antagonism was observed when ETOP was directly combined with 13-cis-RA in SMS-KCNR cells.

We also showed that treatment with 13-cis-RA increased the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, which was associated with blocked apoptotic cell death at the mitochondrial level. Changes in Bcl-xL expression were the most consistent and pronounced in response to 13-cis-RA. The antagonism of the cytotoxic agents by 13-cis-RA was reversed by ABT-737 (41), a small molecule inhibitor of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL.

Induction of apoptotic cell death is a major mechanism by which cytotoxic agents (such as DNA damaging drugs) kill tumor cells (42, 43), and upregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 members by 13-cis-RA likely contributes to decreased sensitivity to cytotoxic treatment by inhibiting the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (44).

Our observation that 13-cis-RA increased Bcl-2 family expression is consistent with a previous report on neuroblastoma response to ATRA (12), and could be biological feature of normal neuronal development. Apoptosis of neuroblasts that fail to achieve synaptic connections is integral to viable neural network development (45), while mature neurons, must last a lifetime and therefore have an inherently high threshold for apoptotic death. Neuronal survival is promoted by upregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins (20).

Our experiments focused on 13-cis-RA, the retinoid used clinically in neuroblastoma, and demonstrated antagonism of activity for several cytotoxic drugs used in neuroblastoma treatment. It is important to note that the antagonism of cytotoxicity by 13-cis-RA was also observed with cell lines selected for RA resistance in vitro and with more than one class of compounds: topoisomerase inhibitors, alkylating agents, and an anthracycline.

Our in vitro data strongly suggest that directly combining the differentiating agent 13-cis-RA with cytotoxic drugs in the clinic could have an adverse effect on tumor response to the cytotoxic agents. As there is no reason to expect that the antagonism observed in vitro would not be also operative in vivo, and as demonstrating significant antagonism requires studying dose-response curves, further studies of the observed antagonism using in vivo models would not be informative or justified.

Even though our data indicate antagonism of conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy by an overlapping treatment of 13-cis-RA with cytotoxic agents, prior treatment with 13-cis-RA in which a substantial interval exists between 13-cis-RA exposure and treatment with cytotoxic agents does not appear to compromise subsequent cytotoxic therapy. For example, our data from in vitro-selected RA-resistant cell lines show that resistance to RA does not result in cross-resistance to cytototoxic chemotherapy. In fact one line selected for retinoic acid resistance (SMS-LHN RR), exhibited increased sensitivity to the cytotoxic agents tested, a response similar to the effect of the cytotoxic retinoid fenretinide on RA-resistant cell lines (22).

In conclusion, our data indicate that overlapping treatments with 13-cis-retinoic acid and cytotoxic agents could diminish tumor response to cytotoxic drugs. Although not investigated in this study, these data also suggest that overlapping treatment of 13-cis RA with radiation should also be avoided unless data are obtained ruling out an antagonistic interaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Min H. Kang, Pharm D for helpful discussions and for providing the structures for Figure 1.

Financial Support:National Cancer Institute CA82830 and CA81403

Abbreviations

- ETOP

Etoposide

- TPT

topotecan

- CDDP

cisplatin

- L-PAM

melphalan

- DOX

doxorubicin hydrochloride

- 13cRA

13-cis-RA

- EtOH

ethanol

- ΔΨm

inner mitochondrial membrane potential

- IC99

concentrations cytotoxic or inhibiting growth for 99% of cells

- M.A.C

maximum clinically achievable

References

- 1.Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Seeger RC, et al. Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and 13-cis-retinoic acid. Children's Cancer Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1165–1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynolds CP. Detection and treatment of minimal residual disease in high-risk neuroblastoma. Pediatr Transplant. 2004;8:56–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-2265.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthay KK, Reynolds CP, Seeger RC, et al. Long-Term Results for Children With High-Risk Neuroblastoma Treated on a Randomized Trial of Myeloablative Therapy Followed by 13-cis-Retinoic Acid: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1007–1013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCaffery PJ, Adams J, Maden M, Rosa-Molinar E. Too much of a good thing: retinoic acid as an endogenous regulator of neural differentiation and exogenous teratogen. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:457–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotan R. Retinoids in cancer chemoprevention. Faseb J. 1996;10:1031–1039. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Q, Stetler-Stevenson M, Steeg PS. Inhibition of cyclin D expression in human breast carcinoma cells by retinoids in vitro. Oncogene. 1997;15:107–115. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen YH, Lavelle D, Desimone J, Uddin S, Platanias LC, Hankewych M. Growth inhibition of a human myeloma cell line by all-trans retinoic acid is not mediated through downregulation of interleukin-6 receptors but through upregulation of p21(WAF1) Blood. 1999;94:251–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borriello A, Cucciolla V, Criscuolo M, et al. Retinoic acid induces p27Kip1 nuclear accumulation by modulating its phosphorylation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4240–4248. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amatruda TT, Sidell N, Ranyard J, Koeffler HP. Retinoic acid treatment of human neuroblastoma cells is associated with decreased N-myc expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;126:1189–1195. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiele CJ, Reynolds CP, Israel MA. Decreased expression of N-myc precedes retinoic acid-induced morphological differentiation of human neuroblastoma. Nature. 1985;313:404–406. doi: 10.1038/313404a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daftary GS, Taylor HS. Endocrine regulation of HOX genes. Endocr Rev. 2006:27331–27355. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasorella A. Differentiation of neuroblastoma enhances Bcl-2 expression and induces alterations of apoptosis and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 1995;15:15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lombet A, Zujovic V, Kandouz M, et al. Resistance to induced apoptosis in the human neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-SH in relation to neuronal differentiation. Role of Bcl-2 protein family. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2001;268:1352–1362. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds CP, Lemons RS. Retinoid therapy of childhood cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001;15:867–910. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds CP, Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Maurer BJ. Retinoid therapy of high-risk neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2003;197:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds CP, Schindler PF, Jones DM, Gentile JL, Proffitt RT, Einhorn PA. Comparison of 13-cis-retinoic acid to trans-retinoic acid using human neuroblastoma cell lines. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1994;385:237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds CP, Kane DJ, Einhorn PA, et al. Response of neuroblastoma to retinoic acid in vitro and in vivo. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1991;366:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenaux P, Chastang C, Chevret S, et al. A randomized comparison of all transretinoic acid (ATRA) followed by chemotherapy and ATRA plus chemotherapy and the role of maintenance therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. The European APL Group. Blood. 1999;94:1192–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adamson PC, Wilson C. Potentiation of cytotoxic drugs with concomitant exposure to retinoids in neuroblastoma. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2006;97:4873. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benn SC, Woolf CJ. Adult neuron survival strategies--slamming on the brakes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:686–700. doi: 10.1038/nrn1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keshelava N, Seeger RC, Groshen S, Reynolds CP. Drug resistance patterns of human neuroblastoma cell lines derived from patients at different phases of therapy. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5396–5405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynolds CP, Wang Y, Melton LJ, Einhorn PA, Slamon DJ, Maurer BJ. Retinoic-acid-resistant neuroblastoma cell lines show altered MYC regulation and high sensitivity to fenretinide. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35:597–602. doi: 10.1002/1096-911x(20001201)35:6<597::aid-mpo23>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins PJ, Hennessy LK, Leibelt CS, Roby RK, Reeder DJ, Foxall PA. Developmental validation of a single-tube amplification of the 13 CODIS STR loci, D2S1338, D19S433, and amelogenin: the AmpFlSTR Identifiler PCR Amplification Kit. J Forensic Sci. 2004;49:1265–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds CP, Biedler JL, Spengler BA, et al. Characterization of human neuroblastoma cell lines established before and after therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;76:375–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frgala T, Kalous O, Proffitt RT, Reynolds CP. A fluorescence microplate cytotoxicity assay with a 4-log dynamic range that identifies synergistic drug combinations. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:886–897. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan AA, Villablanca JG, Reynolds CP, Avramis VI. Pharmacokinetic studies of 13-cis-retinoic acid in pediatric patients with neuroblastoma following bone marrow transplantation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1996;39:34–41. doi: 10.1007/s002800050535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett CL, Sinkule JA, Schilsky RL, Senekjian E, Choi KE. Phase I clinical and pharmacological study of 72-hour continuous infusion of etoposide in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Res. 1987;47:1952–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boos J, Krumpelmann S, Schulze-Westhoff P, Euting T, Berthold F, Jurgens H. Steady-state levels and bone marrow toxicity of etoposide in children and infants: does etoposide require age-dependent dose calculation? J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2954–2960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.12.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hersh MR, Ludden TM, Kuhn JG, Knight WA. Pharmacokinetics of high dose melphalan. Invest New Drugs. 1983;1:331–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00177417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinguet F, Martel P, Fabbro M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose intravenous melphalan in patients undergoing peripheral blood hematopoietic progenitor-cell transplantation. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowinsky EK, Grochow LB, Hendricks CB, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of topotecan: a novel topoisomerase I inhibitor. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:647–656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabbagh R, Leclerc JM, Sunderland M, Theoret Y. Chronopharmacokinetic of a 48-hr continuous infusion of doxorubicin to children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1993;34:198. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tubergen DG, Stewart CF, Pratt CB, et al. Phase I trial and pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) study of topotecan using a five-day course in children with refractory solid tumors: a pediatric oncology group study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;18:352–361. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keshelava N, Groshen S, Reynolds CP. Cross-resistance of topoisomerase I and II inhibitors in neuroblastoma cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;45:1–8. doi: 10.1007/PL00006736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghanem L, Steinman R. A proapoptotic function of p21 in differentiating granulocytes. Leuk Res. 2005;29:1315–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukherjee SB, Das M, Sudhandiran G, Shaha C. Increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels through the activation of non-selective cation channels induced by oxidative stress causes mitochondrial depolarization leading to apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24717–24727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang B, Keshelava N, Anderson CP, Reynolds CP. Antagonism of buthionine sulfoximine cytotoxicity for human neuroblastoma cell lines by hypoxia is reversed by the bioreductive agent tirapazamine. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1520–1526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piqueras B, Autran B, Debre P, Gorochov G. Detection of apoptosis at the single-cell level by direct incorporation of fluorescein-dUTP in DNA strand breaks. Biotechniques. 1996;20:634–640. doi: 10.2144/19962004634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adrain C, Creagh EM, Martin SJ. Apoptosis-associated release of Smac/DIABLO from mitochondria requires active caspases and is blocked by Bcl-2. EMBO J. 2001;20:6627–6636. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cui H, Schroering A, Ding HF. p53 mediates DNA damaging drug-induced apoptosis through a caspase-9-dependent pathway in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:679–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature. 2005;435:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature03579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher DE. Apoptosis in cancer therapy: crossing the threshold. Cell. 1994;78:539–542. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herr I, Debatin KM. Cellular stress response and apoptosis in cancer therapy. Blood. 2001;98:2603–2614. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poulaki V, Mitsiades N, Romero ME, Tsokos M. Fas-mediated apoptosis in neuroblastoma requires mitochondrial activation and is inhibited by FLICE inhibitor protein and Bcl-2. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4864–4872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindsten T, Zong WX, Thompson CB. Defining the role of the Bcl-2 family of proteins in the nervous system. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:10–15. doi: 10.1177/1073858404269267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.