Abstract

Objectives

The purposes of this 36-month study of children with first recognized seizures were: (a) to describe baseline differences in behavior problems between children with and without prior unrecognized seizures; (b) to identify differences over time in behavior problems between children with seizures and their healthy siblings, (c) to identify the proportion of children with seizures and healthy siblings who were consistently at risk for behavior problems for 36 months; and (d) to identify risk factors for behavior problems 36 months following the first recognized seizure. Risk factors explored included demographic (child age and gender, caregiver education), neuropsychological (IQ, processing speed), seizure (epileptic syndrome, use of antiepileptic drug AED, seizure recurrence) and family (family mastery, satisfaction with family relationships, parent response) variables.

Methods

Participants were 300 children ages 6 through 14 years with a first recognized seizure and 196 healthy siblings. Data were collected from medical records, structured interviews, self-report questionnaires, and neuropsychological testing. Behavior problems were measured using the Child Behavior Checklist and the Teacher’s Report Form. Data analyses included descriptive statistics and linear mixed models.

Results

Children with prior unrecognized seizures were at higher risk for behavior problems at baseline. As a group, children with seizures showed a steady reduction in behavior problems over time. Children with seizures were found to have significantly more behavior problems than their siblings over time and significantly more children with seizures (11.3%) than siblings (4.6%) had consistent behavior problems over time. Key risk factors for child behavior problems based on both caregivers and teachers were: less caregiver education, slower initial processing speed, slowing of processing speed over the first 36 months, and a number of family variables including lower levels of family mastery or child satisfaction with family relationships, lower parent support of the child’s autonomy, and lower parent confidence in their ability to discipline their child.

Conclusions

Children with new-onset seizures who are otherwise developing normally have higher rates of behavior problems than their healthy siblings; however, behavior problems are not consistently in the at-risk range in most children during the first three years after seizure onset. When children show behavior problems, family variables that might be targeted include family mastery, parent support of child autonomy, and parent confidence in their ability to handle their children’s behavior.

Keywords: First Seizures, Children, Behavior Problems, Processing Speed, Family Response

It has been established that children with long-standing epilepsy have behavior problems at rates almost 5 times higher than general population children and 2½ times higher than children with other chronic medical conditions (1, 2). Studies investigating children with new onset seizures show that behavior problems occur early in the course of the disorder and, in some children, even precede seizure onset (3-6). In one of the first studies to document this finding, 32% of the children with a first seizure were rated by their parents as having behavior problems in the at-risk range prior to seizure recognition and rates were higher (39.5%) for children who had had prior unrecognized seizures (3).

How behavior problems change over time and the factors associated with these changes, however, are less well documented in children with new onset seizures. In a 4-month follow-up of 42 children with new onset seizures, Dunn et al., 1997 (7) found improvements in total, internalizing, and externalizing problems. The short follow-up period, small sample, and lack of a control group, however, limited the generalizability of this study. In a prospective study of 224 children with first recognized seizures over a 2-year period, Austin et al., 2002 (8) found behavior problems were higher in children with seizures than siblings over time. Oostrom et al., 2003 (9) prospectively compared behavior problems in 66 children with newly diagnosed epilepsy only with a control group. In that study 29% of children with epilepsy had behavior problems that antedated the diagnosis of epilepsy. In two follow-ups of this sample, children with epilepsy were consistently found to have more behavior problems than the control group; however, behavior problems did not persist in the children with epilepsy. During the first 12 months, behavior problems were present at all time-points in only 7 children (9). At the 3.5 year follow-up, behavior problems continued to be inconsistent in individual children (6).

A number of risk factors for behavior problems in children with epilepsy have been identified. However, most research has focused on epilepsy-related variables and findings have been inconsistent (10). For example, recurrent seizures were associated with more behavior problems at 2 years after seizure onset based on both parent ratings (8) and teacher ratings (11). In contrast, Oostrom et al., 2005 (6) failed to find any seizure variables to be related to behavior problems at 3 to 4 years after epilepsy diagnosis. Reasons for the lack of consistency in findings across the studies most likely include differences in inclusion and exclusion criteria (10).

Neuropsychological deficits are common in children with epilepsy and have been identified as a risk factor for behavior problems in this population. Findings in two studies indicated that poorer neuropsychological functioning was associated with more behavior problems (4, 12). Recent research by our team showed that the relationship between changes in neuropsychological functioning and changes in self-esteem were moderated by demographic and family variables. Specifically, younger child age, less parent education, poorer family functioning, and less parental emotional support to the child were risk factors for greater loss in self-esteem when decline in neuropsychological functioning was present (13).

In a review of literature, a number of family variables were also found to be risk factors for the development and maintenance of behavior problems in children with seizures (14). In a 2-year prospective study, decreases in parental emotional support to the child and decreases in parental confidence in their ability to discipline their child were associated with increases in behavior problems in children with new onset seizures (15). A limitation of this study was that seizure variables were not included in the analysis. In another prospective study, maladaptive parenting was the strongest predictor of behavior problems three to four years after diagnosis of epilepsy (6).

To our knowledge there has not been a large, prospective study that described the natural history of behavior problems in children from the time of their first recognized seizure and explored demographic, seizure, neuropsychological, and family risk factors. It was the purpose of this study to address that gap. Research questions were:

Are there differences in behavior problems between children with and without prior unrecognized seizures at baseline?

Do behavior problems differ between children with seizures and their siblings from baseline to 36 months?

What proportion of children and siblings are consistently at risk for behavior problems during the first 3 years?

Which of the following are risk factors for behavior problems in children with seizures over the first 36 months: demographic (child age and gender, parent education); neuropsychological (IQ, processing speed), epileptic syndrome (idiopathic vs. symptomatic/cryptogenic), use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) (never, partial, continuous), seizure recurrence (no recurrence, recurrence, persistent); and family (mastery, satisfaction with family relationships, parent response).

Findings were expected to provide important information on the natural course of behavior problems in children with a first seizure and to identify the children who are most vulnerable to behavior problems as well as risk factors that should be targeted for interventions.

Methods

Participants

Children ages 6 through 14 years who had had a first recognized seizure within the preceding 3 months were recruited at two academic medical centers in Indianapolis and Cincinnati. In Indiana, children were also recruited through private pediatric neurology practices and fliers to school nurses. Exclusion criteria were: a provoked seizure (e.g., infection, trauma) or a chronic health condition or impairment that limited activities of daily living. Site institutional review boards approved the study. Parents gave written consent and children assent.

The sample for the current study was restricted to children who had an IQ in the normal range and data on behavior problems at baseline and at least one follow-up. Of the 349 children in the larger study, 23 had estimated IQs less than 70. Of the remaining 326, 13 did not have any data on behavior problems, 11 were missing these data at all follow-up visits, and 2 were missing baseline data on behavior problems. At baseline and 9 months there were 300 children in the sample. At 18, 27, and 36 months the sample size was 277, 274, and 260, respectively. Although the final sample of 300 did not differ (p > .10) on age, sex, caregiver education, prior unrecognized seizures, seizure type, or epileptic syndrome from the 26 children missing baseline or with fewer than two data collections on behavior problems, there was a lower proportion of non-Caucasian children in the final sample compared to the 26 (14% vs. 54%, p < 0.0001).

Data Source and Collection Procedures

The primary caregiving parent (92% mothers) provided data on demographic, seizure, family, and parent response variables using Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI). Children also provided data on mental health and family variables using CATI. Parents reported on seizure frequency and use of AEDs at baseline, 9 months, 18 months, 27 months, and 36 months. Parents rated their children’s behavior problems five times: baseline, 9 months, 18 months, 27 months, and 36 months. Data from medical records were collected at baseline, 18 months, and 36 months. Teachers rated behavior problems in children with seizures at baseline, 18 months, and 36 months. Baseline data were collected within 3 months of the first recognized seizure. For behavior problems and family variables at baseline, parents were asked to rate the 6-month period prior to the first recognized seizure. To obtain baseline data for behavior at school, teachers were asked to rate the child with the seizure during the 2-month period that was prior to the first recognized seizure. Teachers were not informed that the children had had a seizure nor were teachers informed by the researchers that the child was on an AED. Neuropsychological data were obtained via individual testing of the children at baseline, 18 months, and 36 months.

Measurement

Demographic Variables

The child’s exact age was used in analyses. Age was calculated as date of first recognized seizure minus date of birth, divided by 365.25. Caregiver education level was measured to the nearest year beginning with Grade 1.

Seizure Variables

Board-certified child neurologists classified seizure type and epileptic syndrome using International League Against Epilepsy criteria (16, 17) and based on review of medical records and the parent’s description of the child’s seizure(s). EEG data were available for 99% and imaging data were available for 94% (88.3% had MRI and 5.7% had CT). At 36 months all available data from medical records and parent reports on seizures were used to classify seizure etiology (idiopathic or symptomatic/cryptogenic) and use of AEDs. At every interview parents were asked if their child had had any seizure-like events prior to the first recognized seizure. If any such events had occurred, parents were asked to describe these events in detail including the child’s activity before, during, and after the event. Author DWD read descriptions of all events for each child and rated the likelihood (highly unlikely to highly likely) that the event was a seizure. Only those seizure-like events that were judged as highly likely to be a seizure were considered to be a prior unrecognized seizure.

Seizure frequency was categorized into three groups for analysis. Children with no further seizures except the first recognized one were placed into the “no recurrent seizure” group. Children with at least one additional seizure but did not report a seizure at each data collection period were placed into the “recurrent seizure” group. Children who had seizures at every data collection period were placed into the “persistent seizures” group. Four syndrome groups were used for data analysis: generalized idiopathic - absence, generalized idiopathic – tonic clonic, partial idiopathic, and partial cryptogenic/symptomatic. There were too few children with a generalized cryptogenic/symptomatic syndrome to include them in analysis related to epileptic syndrome.

Neuropsychological Testing

For the larger study a battery of well standardized neuropsychological tests was used to test the children. Testing was carried out within 6 months (M = 2.8, SD = 1.3) of the first recognized seizure, 18 months, and 36 months later (M = 35.6, SD =3.1). Test scores were converted to age-corrected standardized scores. Four factors were obtained from a factor analysis of the test battery: Language, Processing Speed, Attention/ Executive/Construction, and Verbal Memory and Learning (18). For the proposed study IQ and processing speed were explored as risk factors. IQ was selected because it has been found to be related to behavior problems in prior research (4). IQ was estimated by the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (19). Processing speed, which refers to how fast the child can complete complex cognitive tasks, was selected because it was the only area of neuropsychological functioning in which children with seizures had a greater decline than their healthy siblings (13, 20, 21). The processing speed variable in this study was measured by a factor comprised of Coding and Symbol Search subtests from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 3rd Ed. (22) and the Rapid Naming Composite Score from the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (23). Collectively, these three tests reflect the speed of information processing. For all processing speed measures, higher scores reflected faster processing speed. Change in IQ and processing speed was calculated as the difference between the child’s initial and final scores (final – initial). In most cases the initial collection was baseline (96% for IQ and 94% for processing speed) and the final data collection was 36 months (74% for IQ and 70% for processing speed).

Behavior Problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (24) was administered to the primary caregiver to measure behavior problems. The 118-item CBCL asks caregivers to rate the child’s behavior during the past 6 months using 3-point scales of 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). Caregivers were instructed to exclude any behaviors that might have been seizure activity or were associated with a seizure episode. The child’s teacher was asked to complete the Child Behavior Checklist Teacher’s Report Form, (TRF) (25) based on the child’s behavior during the past 2 months. Teachers’ ratings were obtained because they provide a different source of ratings of the child’s behavior as well as a different setting in which the child is observed. Each item is rated on a 3-point scale: (0) not true, (1) somewhat or sometimes true, and (2) very or often true. The reliability and validity of the CBCL and TRF as well as norms based on age and gender have been established in past research (24, 25).

On the CBCL and the TRF, T-scores (M = 50, SD = 10) were computed for total behavior problems, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems. Syndromes of anxious/depressed behavior, withdrawn/depressed behavior, and somatic complaints together form the broad-band dimension of internalizing problems, whereas syndromes of aggressive and delinquent behavior form the broad-band dimension of externalizing behavior. The total behavior problems score consists of the internalizing and externalizing broad-band dimensions as well as the syndromes of thought problems, attention problems, and social problems. For all scores on the CBCL and the TRF, higher scores reflect more problems.

Definition of risk for behavior problems

For the total, internalizing, and externalizing behavior problems on both the CBCL and TRF, T-scores ≥ 60 were considered to be at risk for problems. For the syndrome scores, T-Scores ≥ 67 were considered at risk. Children were considered to be consistently at risk for behavior problems if their total behavior problems score was in the at-risk range each time it was measured.

Family Variables

Measurements of family mastery, satisfaction with family relationships, and parent response (defined below) at the parent’s final data collection were used to obtain a measurement of parental perceptions and family environment occurring after the initial response to seizures when the family had had time to adjust to having a child with seizures. We selected data from the parents’ final data collection for analysis because we believed that parent perceptions related to seizures and the family environment would be most stable at that time. In 87% of cases the final data collection was at 36 months. Satisfaction with family relationships total scores and family mastery and parent response mean scores were used in analyses.

Family Mastery

Family mastery, a subscale of the Family Inventory of Resources for Management (26), was used to measure how well the family unit is working together to solve problems and to support each other. Parents were asked to respond to items on 4-point scales ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very well), with a higher score reflecting greater mastery. For this sample, the mean was 2.33 (SD .50; range 0-3) and the Cronbach alpha was .92.

Family Satisfaction

The Family APGAR (27) was completed by parents and the Revised Family APGAR (28) was completed by children to measure satisfaction with family relationships. Both scales have 5 items that ask respondents to rate attributes of the family: adaptation, partnership, growth, affection, and resolve. Respondents select how often they are satisfied with those aspects of the family on 5-point scales of 1 (never) to 5 (always). Scores have a range of 1-5 and higher scores reflect greater satisfaction. Psychometric properties for this sample were: Family APGAR (M= 3.19 [SD=0.73], α = .88 and Revised Family APGAR (M=3.09 [SD=0.66], α = .81.

Parent Response

Parent response to seizures in a child was measured using four subscales (Child Support, Family Life/Leisure, Child Autonomy, and Child Discipline) on the Parent Response to Child Illness scale (29). These subscales reflect parent-child interactions and family leisure activities in the context of seizures. Child support measures the parent’s emotional support to the child, family life/leisure measures how the family incorporates seizures into daily life, child autonomy measures the parent’s support of the child’s independence, and child discipline measures how confident the parent feels to handle the child’s behavior. Parents rate level of agreement to items on 5-point scales of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Each subscale has a range of 1-5 and higher scores reflect a more adaptive response (e.g., greater child support). Psychometric properties for this sample were: child support (M=4.36 [SD=.46], α =.72; family life/leisure (M=4.47 [SD=.54], α = .88; child autonomy (M=3.48 [SD=.62], α = .59; and child discipline (M=3.89 [SD=.64], α = .78.

Statistical Methods

Comparison Analyses

Baseline behavior problems by prior unrecognized seizures

Chi-square tests were performed to compare the percent of children with and without prior unrecognized seizures who were at risk for total, internalizing, and externalizing behavior problems at baseline. Hochberg’s step-up Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was used for the pair-wise comparisons. To determine if behavior problems in children with prior unrecognized seizures were related to epileptic syndrome, linear mixed models were used to test for differences in behavior problems between siblings and children with prior seizures for four syndrome groups: generalized idiopathic-absence; generalized idiopathic-tonic clonic; partial idiopathic; and partial cryptogenic/symptomatic. There were too few children with a generalized cryptogenic/symptomatic syndrome to include them in the analysis.

Comparing behavior over time between children with seizures and siblings

For comparisons between the children with seizures and siblings, longitudinal linear mixed models were used to compare CBCL behavior problem scores over time (baseline, 9, months, 18 months, 27 months, and 36 months). A compound symmetry variance-covariance structure was assumed. Family was a random effect, and child (either child with seizures or sibling) was a fixed effect. The child-by-time interaction was included. If the interaction term was significant at the 0.10 level, pair-wise tests were done comparing children with seizures and their siblings’ scores at each visit, as well as testing for a time effect separately for children with seizures and siblings. Hochberg’s step-up Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was used for the pair-wise comparisons.

Proportions at risk for behavior problems

The proportion of children and siblings with CBCL scores in the at-risk range at each time, as well as the proportion of children and siblings who were consistently at risk, were calculated. These same proportions were also calculated for the TRF scores.

Identification of risk factors

Demographic (child age and gender, caregiver education), neuropsychological (IQ and processing speed – both initial and change), seizure (epileptic syndrome, use of AEDs, seizure recurrence), and family risk factors (family mastery, parent and child satisfaction with family relationships, child support, family life/leisure, child autonomy, and child discipline) were examined. To identify risk factors, longitudinal linear mixed models were used to investigate the association between each risk factor and CBCL total behavior problem score over time (baseline, 9 months, 18 months, 27 months, and 36 months) and TRF total behavior problem score over time (baseline, 18 months, and 36 months). A compound symmetry variance-covariance structure was assumed. Family was a random effect and risk factor was a fixed effect. The risk factor-by-time interaction was included. If the interaction term was significant at the 0.10 level, pair-wise tests examining the association between the risk factor and the problem score were carried out for each visit. Hochberg’s step-up Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was used for the pair-wise comparisons. Standardized betas (adjusted correlation coefficients) are presented. Given the large number of family variables examined, bivariate correlations between them were explored with Pearson correlations. Next, to explore which risk factors may be independent risk factors, a multivariable analysis was carried out using the CBCL total behavior problem score as the outcome and all risk factors (including interactions with time) that were significant in the above univariate models. A similar analysis was completed for the TRF total behavior problems score.

Results

Because the parents’ ratings of the children’s behavior on the CBCL were the primary focus of this paper, results for CBCL are presented first. They are followed by a briefer section with results using teachers’ ratings on the TRF.

Sample Description

The mean age of the children when seizures were first recognized (baseline) was 9.75 years and at 36 months was 12.76 years. Siblings were slightly older (M = 10.04 years at baseline). Caregiver education ranged from 9 to 20 years with a mean of 13.90 (SD = 2.27). Among the children with seizures, 91.6% had one seizure type, approximately half (48.7%) had idiopathic epileptic syndromes, and a small percentage (8.7%) had symptomatic epileptic syndromes. Prior unrecognized seizures were identified in 107 (35.7%) children at baseline. During the 36 months, the majority had at least one recurrent seizure (76.0%). There were 40 (13%) children who had persistent seizures. During the 36-month period, the majority of the children (74.0%) were treated with an AED for some period. Of the 63.1% of children who were receiving an AED at 36 months, 84.3% were on monotherapy. See Table 1 for demographic and seizure information for the total sample and for children with prior and no prior unrecognized seizures. As would be expected, the percentage of children with generalized idiopathic absence syndrome was higher in the prior seizures group.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics for Children with Seizures and Siblings

| Total Sample | Prior Seizures | No Prior Seizures | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children with Seizures | n = 300 | n=107 | n=193 |

| Age in Years at Baseline (Mean [SD]) | 9.75 (2.58) | 9.50 (2.41) | 9.89 (2.67) |

| IQ (Mean [SD]) | 102.93 (13.24) | 102.33 (14.15) | 103.27 (12.73) |

| Sex (% Female) | 51.3 | 65.4 | 43.5 |

| Race (% Caucasian/Non-Hispanic) | 85.7 | 81.3 | 88.1 |

| Multiple Seizure Types (%) | 8.4 | 12.1 | 6.2 |

| Primary Seizure Type (%) | |||

| Generalized Non-Absence | 24.3 | 21.5 | 25.9 |

| Generalized Absence | 13.3 | 23.4 | 7.8 |

| Simple Partial | 7.0 | 8.4 | 6.2 |

| Complex Partial | 21.7 | 17.8 | 23.8 |

| Partial w/Secondary Generalization | 32.0 | 28.0 | 34.2 |

| Undetermined | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.1 |

| Primary Epileptic Syndrome (%) | |||

| Generalized Idiopathic Absence | 12.7 | 22.4 | 7.3 |

| Generalized Idiopathic Tonic Clonic | 17.3 | 14.0 | 19.2 |

| Generalized Symptomatic/Cryptogenic | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.1 |

| Partial Idiopathic | 18.7 | 14.0 | 21.2 |

| Partial Cryptogenic | 37.3 | 36.5 | 37.8 |

| Partial Symptomatic | 7.0 | 8.4 | 6.2 |

| Undetermined | 5.3 | 3.7 | 6.2 |

| Recurrent seizure during 36 months (%Yes) | 76.0 | 89.7 | 68.4 |

| Persistent seizures during 36 months (% Yes) | 13.0 | 20.6 | 9.3 |

| Treatment with medication during 36 months (% Yes) | 74.0 | 87.9 | 66.3 |

| All of the time | 45.0 | 55.2 | 39.4 |

| Some of the time | 29.0 | 32.7 | 26.9 |

| None of the time | 26.0 | 12.1 | 33.7 |

| Siblings | n = 196 | ||

| Age in Years at Baseline (Mean [SD]) | 10.04 (3.64) | ||

| IQ (Mean [SD]) | 104.98 (12.59) | ||

| Sex (% Female) | 52.0 | ||

| Race (% Caucasian/Non-Hispanic) | 87.2 |

1. Comparison of risk for behavior problems for children with and without prior unrecognized seizures at baseline

Based on the CBCL, a significantly greater proportion of children with prior unrecognized seizures were at risk for total and internalizing behavior problems at baseline (p = 0.04 and p = 0.02, respectively) than were children without prior seizures. Among children with prior seizures, 42.1% and 41.1% were at risk for total and internalizing behavior problems, respectively, as opposed to 29.0% and 25.9% among children without prior seizures. No significant differences were found between these two groups on the externalizing behavior problems score. To further explore differences by syndrome, follow-up analyses were conducted to compare mean CBCL total behavior problem scores of siblings to scores for prior and no prior unrecognized seizure groups for each of the epileptic syndromes. In both the prior and no prior seizure groups, children with generalized idiopathic absence and partial symptomatic/cryptogenic syndromes had significantly higher mean total behavior problem scores than siblings. Children with generalized idiopathic tonic-clonic syndrome had significantly higher mean total behavior problem scores than siblings only in the prior unrecognized seizure group. In contrast, children with partial idiopathic syndrome did not differ from siblings on mean total behavior problems in either group.

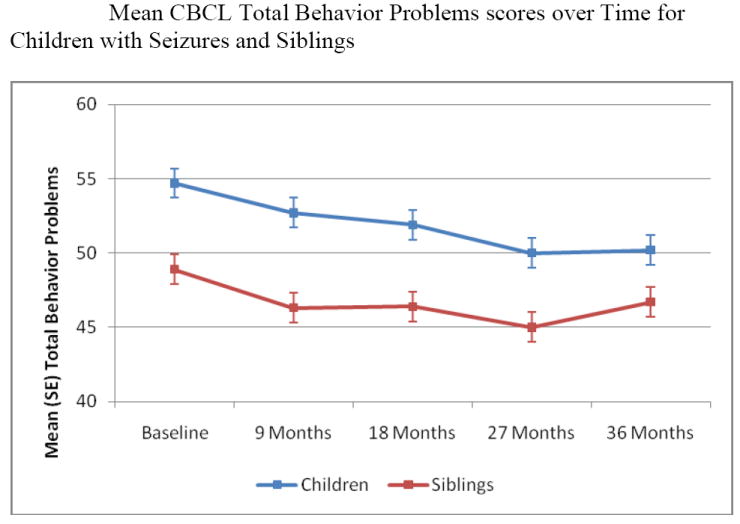

2. Comparisons between children with seizures and their siblings on behavior problems

There was a significant child-by-time interaction for CBCL total behavior problem scores (p = 0.0549). Children with seizures had significantly higher total problem scores than their siblings at all times, but the difference was greater at earlier visits (Figure 1). They also had significantly higher internalizing and externalizing problem scores (p < .05) than their siblings at all times. Children with seizures had significantly higher problem scores (p < 0.05) than siblings at each visit on all syndrome scores except for delinquent behavior. There was a significant child-by-time interaction for somatic complaints, thought problems, and attention problems. Although children with seizures had significantly more somatic complaints, thought problems, and attention problems at all time-points, the difference was greater at earlier visits.

Figure 1.

Children with seizures had significantly higher total behavior problem scores than their siblings at all times, but the difference was greater at earlier visits.

3. Percentages of children and siblings who were consistently at risk for behavior problems

At baseline 33.7% of the children with seizures and 17.4% of siblings had CBCL total behavior problems scores in the at-risk range based on parent report (Table 2). The percentage of children with seizures and siblings whose parents consistently rated them in the at-risk range over the 36 months was 11.3% and 4.6%, respectively. These percentages were significantly different (p < .0035). When seizure occurrence was explored in relation to being at risk for total behavior problems scores, rates were 15%, 12.8%, and 5.6% for persistent, recurrent, and no recurrent seizure groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Percents of Children with Seizures and Siblings in At-Risk Range for Behavior Problems

| Parent Report—CBCL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 9 Months | 18 Months | 27 Months | 36 Months | Consistent Risk | |

| Child CBCL | % at risk | % at risk | % at risk | % at risk | % at risk | % at risk |

| Total Problems | 33.7 | 27.7 | 27.1 | 21.5 | 20.8 | 11.3 |

| Internalizing | 31.3 | 26.7 | 21.7 | 20.4 | 18.9 | 8.3 |

| Externalizing | 23.3 | 23.0 | 23.5 | 15.0 | 16.2 | 6.7 |

| Withdrawal | 10.7 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 6.9 | 4.6 | 1.3 |

| Somatic Complaints | 15.7 | 11.7 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 1.7 |

| Anxious/Depressed | 12.7 | 11.7 | 10.5 | 8.8 | 5.4 | 2.7 |

| Social Problems | 14.1 | 11.7 | 9.4 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 2.7 |

| Thought Problems | 16.1 | 7.0 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 0.3 |

| Attention Problems | 22.3 | 19.3 | 14.8 | 13.9 | 10.8 | 4.7 |

| Delinquent Behavior | 7.7 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 0.7 |

| Aggressive Behavior | 12.0 | 11.7 | 8.7 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 2.7 |

| Child TRF | Teacher Report–TRF | |||||

| Total Problems | 29.6 | 28.6 | 24.1 | 7.6 | ||

| Internalizing | 28.2 | 26.3 | 25.3 | 3.1 | ||

| Externalizing | 20.1 | 17.0 | 15.6 | 4.2 | ||

| Withdrawal | 9.2 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 5.0 | ||

| Somatic Complaints | 14.4 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 2.7 | ||

| Anxious/Depressed | 7.0 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 2.7 | ||

| Social Problems | 10.2 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 7.6 | ||

| Thought Problems | 8.5 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 4.6 | ||

| Attention Problems | 12.7 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 7.3 | ||

| Delinquent Behavior | 5.6 | 5.0 | 5.9 | 2.3 | ||

| Aggressive Behavior | 8.1 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 5.3 | ||

| Sibling CBCL | Parent Report—CBCL | |||||

| Total Problems | 17.4 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 15.7 | 4.6 |

| Internalizing | 18.9 | 14.1 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 11.3 | 2.6 |

| Externalizing | 18.4 | 15.1 | 14.5 | 11.2 | 15.1 | 4.1 |

| Withdrawal | 6.6 | 7.8 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 |

| Somatic Complaints | 6.1 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 0.5 |

| Anxious/Depressed | 5.6 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.0 |

| Social Problems | 5.3 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 6.0 | 2.1 |

| Thought Problems | 3.5 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 1.0 |

| Attention Problems | 7.7 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1.0 |

| Delinquent Behavior | 8.2 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 1.0 |

| Aggressive Behavior | 9.2 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 4.1 | 5.7 | 1.5 |

4. Risk factors for behavior problems over first 36 months

Demographic risk factors

Child gender was not significantly associated with total behavior problems at any time. There was a significant interaction effect between age at first seizure and time on CBCL total behavior problems (p < 0.0001). Behavior problems began to improve in older children at 9 months after their first seizure, but did not begin to improve in younger children until 27 months later. Less caregiver education was significantly associated with more total behavior problems at all times (β = -0.07, p = 0.0038).

Neuropsychological risk factors

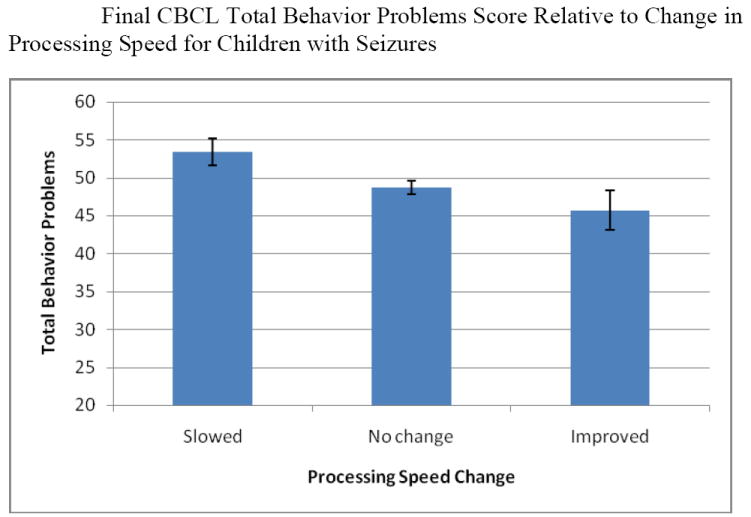

Both lower initial IQ and processing speed scores were significantly associated with more CBCL total behavior problems scores at all time-points (β = -0.02, p < 0.0001; β = -0.31, p < 0.0001). When exploring change in neuropsychological functioning, there was no association between change in IQ and total behavior problems at any time point. However, there was a significant difference in processing speed score by change over time on total problems scores (p = 0.0006). Change in processing speed was not associated with total problems at baseline, 9 months, or 18 months; however, slowing of processing speed scores were significantly associated with more problems at 27 and 36 months (β = -0.32, p = 0.0136; β = -0.38, p = 0.0035, respectively). To display this finding we show differences in total behavior problems scores for change in processing speed in Figure 2. Children with seizures were subdivided into three groups depending on whether they changed from the initial to final measurement of processing speed more than 1 SD relative to mean sibling change in processing speed; 55 had slowing of processing speed, 162 stayed the same, and 18 had improving processing speed.

Figure 2.

Mean total behavior problem scores for children whose processing speed slowed by at least 1 SD (n = 55), did not change more than 1 SD (n = 162), or improved 1 SD (n = 18) from initial measurement to 36-month measurement of processing speed based on sibling data.

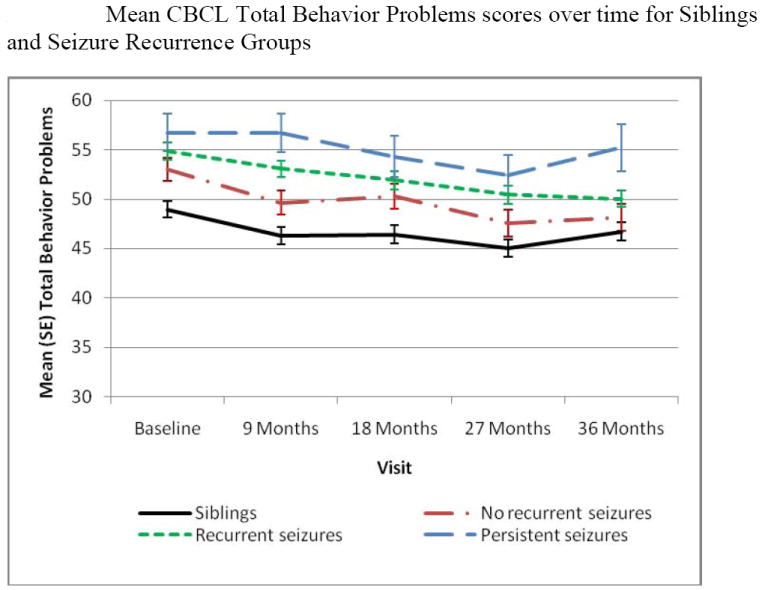

Seizure risk factors

For the parent ratings, neither epileptic syndrome nor use of AEDs was significantly associated with CBCL total behavior problems scores at any time. There was a significant interaction effect between seizure recurrence and time on total behavior problems scores (p = 0.0398). At baseline and 18 months there was not a significant effect of seizure recurrence on behavior problems. At 9 and 36 months, children with persistent seizures had higher total behavior problem scores than children with no recurrent seizures (β = -060, p = 0.0066; β = -0.63, p = 0.0054, respectively). At 27 and 36 months, children with persistent seizures had higher total behavior problem scores than children with recurrent seizures (β = -0.19, p = 0.0219; β = -0.51, p = 0.0082, respectively). To display this finding we show differences in total behavior problems scores for seizure recurrence in Figure 3. At 36 months, the mean total behavior problem score was 55.2 for children with persistent seizures, 50.0 for children with recurrent seizures, and 48.2 for children with no recurrent seizures.

Figure 3.

Mean total behavior problems over time for siblings and three seizure recurrence groups: no recurrent seizure, recurrent seizure(s), and persistent seizures.

Family risk factors

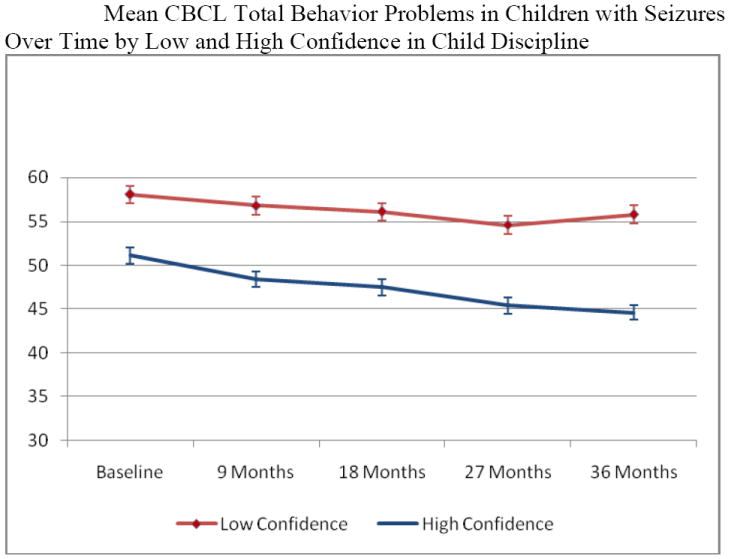

Lower family mastery (β = -0.84, p < 0.0001) and parent and child satisfaction with family relationships (β = -0.08, p < 0.0001; β = -0.05, p = 0. 0014), respectively, were significantly associated with more behavior problems across time. Both lower family life/leisure and lower child autonomy scores were significantly associated with higher total behavior problems scores across time (β = -0.47, p < 0.0001; β = -0.52, p < 0.0001, respectively).

Both child support-by-time and child discipline-by-time interactions on total behavior problems were significant (p = 0.0004 and p < 0.0001). Less emotional support to the child and lower parent perception of their ability to discipline their child were significantly associated with more total behavior problems at all times. The strength of the association increased over time (child support β: -0.34, -0.54, -0.49, -0.62, and -0.72 at baseline, 9, 18, 27, and 36 months, respectively; child discipline β: -0.55, -0.60, -0.63, -0.72, and -0.85 at baseline, 9, 18, 27, and 36 months, respectively). To display one of these similar findings we placed the children into low and high child discipline groups and show how they are associated with total behavior problems scores at each time point (Figure 4). Pearson correlations among family variables ranged between .03 and .47 with two exceptions. Family mastery was highly correlated (r= .60) with parent rating of satisfaction of the family relationship and parent emotional support to the child was highly correlated (r= .62) with parent confidence in their ability to discipline their child. When we fit all significant risk factors together in a single multivariable model, caregiver education, slower initial processing speed, slowing of processing speed over the 36 months, and three family variables remained significant (family mastery, child autonomy, and child discipline) with effects consistent with the univariate analyses (results available upon request).

Figure 4.

Change in mean total behavior problems score for each data collection period by low and high levels of level of parent response of child discipline. A higher score reflected greater parent confidence in their ability to handle their children’s behavior.

Results for Teachers’ Ratings on TRF

For prior vs. no prior seizures, teachers’ scores were in the same direction as parents, but did not reach statistical significance. Percentages of children with prior unrecognized seizures rated to be at risk for total, internalizing, and externalizing problems respectively were 33.0%, 33.0%, and 20.4%. For those without prior seizures, scores were 27.6%, 25.4%, and 19.9%, respectively. As can be seen in Table 2, percentages of teachers’ ratings of children with seizures to be in the at-risk range were 29.6%, 28.6%, and 24.1% at baseline, 18 months, and 36 months, respectively. Only 7.6% were consistently rated by teachers to be in the at-risk range. Percents of children in the at-risk range on total behavior problems scores were 10.8%, 9.8%, and 0.0% for persistent, recurrent, and no recurrent seizure groups, respectively.

When exploring risk factors, findings were similar to parents. The only significant demographic factor was lower caregiver education. Slowing of processing speed over the first 36 months was significantly associated with higher problem scores at every time point, but the strength did not vary over time. Compared to parent ratings, more seizure variables were risk factors for problems on teachers’ ratings of behavior. Seizure recurrence was significantly associated with behavior problems. Children with persistent seizures had significantly higher behavior problem scores than children with either recurrent or no recurrent seizures. Children with recurrent seizures had significantly higher problem scores than those with no recurrent seizures. Epileptic syndrome was significantly associated with behavior problem scores at all times. Children with partial idiopathic seizures had significantly lower behavior problem scores than children with partial cryptogenic/symptomatic seizures. Use of AEDs was significantly associated with higher total behavior problems scores.

Family risk factors were similar to parent findings. Lower family mastery, parent and child satisfaction with family relationships, family/life leisure, and parent support of child autonomy were significant risk factors for behavior problems. In addition, parent responses of lower child support and lower child discipline were significantly associated with more behavior problems over time. When we fit all significant risk factors together in a single multivariable model, caregiver education, epileptic syndrome, slower initial processing speed, slowing in processing speed over the first 36 months, and three family variables (child satisfaction with family relationships, child autonomy, and child discipline) remained significant with effects consistent with the univariate analyses (results available upon request).

Discussion

Four major findings emerged from this 3-year prospective study of behavior problems in children starting at the time of their first recognized seizure. First, children with seizures were at risk for behavior problems at baseline, especially those with prior unrecognized seizures. Among children with prior seizures, those with partial idiopathic syndrome were least at risk for behavior problems. Second, although children with seizures had significantly more behavior problems than their siblings during the entire time period, problems showed an overall improvement over time and mean scores were better than what is generally found in samples of children with long-standing seizures. Third, consistent behavior problems were observed in only about 11% of children with seizures. Fourth, key risk factors for child behavior problems based on both caregivers and teachers were: less caregiver education, slower initial processing speed, slowing of processing speed over the 36 months, and a number of family variables including lower levels of family mastery or child satisfaction with family relationships, lower parent support of the child’s autonomy, and lower parent confidence in their ability to discipline their child. Limitations of the study included the small number of children who had either persistent seizures or symptomatic epileptic syndromes. In addition, it was not known if parents informed the teachers about the child’s seizure condition or use of AEDs, which might have influenced their ratings of behavior.

Behavior problems over time

In this study we found empirical support from both parents and teachers for higher rates of behavior problems in children with a first recognized seizure during the period prior to the first recognized seizure. These early behavior problems are consistent not only with our past research (3) but with recent research by others (30). We also replicated past findings showing that children who had had prior unrecognized seizures are especially at risk for behavior problems (3). In that study the percentage of children without prior seizures who were at risk for behavior problems was lower (19.6%) than in the current study (29.0%), however, percentages were similar for siblings (~17%). Teachers’ ratings were in the same direction but did not reach statistical significance, which is in contrast to findings in our prior study (11, 31). One explanation might be that parents were more carefully monitoring their children because these children were showing more behavior problems. Another explanation might be that mothers were the primary informant and past research has shown that mothers tend to report more behavior problems in children with epilepsy than teachers (28, 32). However, as shown in Table 2 more teachers than parents rated children to be in the at-risk range for internalizing problems at 18 and 36 months and rated more children to be consistently at risk for social problems and attention problems.

Children with seizures were particularly at risk for attention problems and somatic complaints. These findings are consistent with a recent review of literature on psychopathology in children with epilepsy (33) and with recent studies of children with epilepsy (30, 34). Attention problems have been investigated using instruments designed to more delineate the specific nature of attention difficulties (11, 31). In contrast, somatic complaints, which also have been noted previously (33), have not been investigated sufficiently to understand the exact nature of these problems. More research is needed on somatic problems.

Although the proportion of children in the at-risk range for behavior problems declined steadily over time in both children with seizures and their siblings, children with seizures had significantly more problems than siblings at every time period. The difference became smaller over time with children with seizures improving slightly more than did siblings. Similar to findings by Oostrom and colleagues (2003) (9), behavior problems persisted in only a small percentage of children over the 36 months. The generally low rates of behavior problems found in this study might be explained by the composition of the sample. All children had an estimated IQ in the normal range and were otherwise developing normally. Moreover, most had mild conditions with only 13% having persistent seizures, 24% having only one seizure, and 26% never being treated with AED medication. These findings indicate that on average during the first three years after seizure onset behavior problems generally improve in children who are otherwise developing normally. One explanation for the improvement in behavior in children with few to no further seizures might be that both the children and their families are making a positive adjustment to the onset of a new condition. Moreover, the lack of behavioral improvement in children with persistent seizures might indicate that they have more severe underlying neurological condition as well as a more difficult adjustment because of the challenges of repeated seizures.

Few demographic variables were risk factors

In this study less caregiver education, which was included to reflect socioeconomic status, was the only demographic variable to be associated with child behavior problems. This finding is consistent with our past prospective study (8) and a recent study showing lower socioeconomic status to be associated with more behavior problems (30). In contrast to our prior research (8), neither sex of child nor child age was significantly associated with total behavior problems at any time. These findings, however, are consistent with most studies, which have not shown a relationship between age of onset and behavior problems (10).

Seizures and poorer neuropsychological functioning were risk factors for behavior problems

Although a recent review of the literature found no consistent pattern between seizure variables and behavior problems (10), our team has consistently found an association between seizure recurrence and more behavior problems (8). Moreover, in this study the 5- and 7- point differences in behavior problems at 36 months between persistent seizure and recurrent and no recurrent seizure groups, respectively, are of clinical significance because they meet or exceed the degree of difference generally found to be of clinical significance (i.e., difference of ≥ ½ SD) (35).

Epileptic syndrome and AEDs were not associated with parents’ ratings of behavior problems over time, however, among children with prior unrecognized seizures, those with generalized idiopathic and partial cryptogenic/symptomatic syndromes fared worse than siblings. In addition, for teachers’ ratings, behavior problems were relatively higher for children with partial cryptogenic/symptomatic seizures and children on AEDs. Although we were not able to fully explore epileptic syndrome, because of the small number of children with cryptogenic and symptomatic generalized epilepsy syndromes and partial symptomatic syndrome, our findings suggest that underlying neurological disorder that is associated with cryptogenic/symptomatic syndromes is associated with more behavior problems.

Both slower initial processing speed and a slowing of processing speed over the 36 months were associated with higher levels of behavior problems as rated by both caregivers and teachers. Processing speed deficits and slowing in processing speed have been previously found in children with uncomplicated epilepsy (36-38). Moreover, deficits in processing speed have been associated with higher depressed mood in persons with multiple sclerosis (39). Berg et al., 2008 (37) suggest that the underlying disturbance that contributes to seizures also contributes to inefficiency in processing. Our findings that both behavioral problems and processing speed deficits are evident at onset, and that slowing of processing speed over time is associated with more behavior problems at 36 months, might indicate that other mechanisms such as underlying pathology, subclinical epileptiform discharges, transient cognitive impairment, metabolic effects of seizures, or subtle effects of AEDs (40, 41) are accounting for both the slow processing speed and the behavior problems.

Family risk factors for behavior problems

The family variables that were risk factors in this study are consistent with prior research showing that both the family environment and parenting behaviors are strongly associated with behavior problems in children with epilepsy (10, 14, 33, 42, 43). These findings are especially robust because relationships were significant for both parents’ and teachers’ ratings of children’s behavior problems. Relationships between family variables and child problems on the CBCL might be expected because the same caregiver rated the child’s behavior each time and also provided ratings for most family variables. However, the consistency across teachers’ ratings of behavior problems and their strong associations with family variables are striking considering that in most cases three different teachers rated the children’s behavior over the 36 months.

In this study, lower family mastery was associated with more child behavior problems. However, even in this prospective study it is difficult to sort out the temporal order or how child behavior problems and family dysfunction influence each other. Because behavior problems were found at baseline for the 6-month period prior to the first recognized seizure, it might be that child behavior problems contributed in part to increased family dysfunction.

Past research strongly supports that the onset of seizures in a child can be most disruptive to continuity of parenting. Slightly less than half of parents reported that their child’s seizures were emotionally overwhelming and negatively affecting the continuity of parenting (42). In this study there was a strong relationship between parent response variables and child behavior problems over time. Even when all variables were included in a multiple regression, parent encouragement of child autonomy and parent perception of their ability to discipline their child were significantly associated with more total behavior problems across time. These findings are consistent with a prior prospective study by our team (15) and suggest that over time dysfunctional patterns of parenting may form. In prior research our team found that reductions in emotional support to the child were associated with increased child internalizing problems (15). Overall, the finding that three family variables were significant after controlling for significant demographic, neuropsychological, and seizure variables for both parent and teacher ratings of behavior strongly indicate that interventions aimed at addressing behavior problems in children with seizures should focus prominently on parenting behaviors and the family environment. Interventions should focus on improving mastery in the family environment, enhancing parent encouragement of child autonomy, and helping parents increase their competence in handling their children’s behavior.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS22416: PI: J. K. Austin). The authors acknowledge Angela McNelis and Janet Kain for coordinating interviews; Beverly Musick for coordinating data management; Carolanne Benson and Paul Buelow for technical and administrative support, and Phyllis Dexter for editorial support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication, and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines. None of the authors has a conflict of interest in this publication.

References

- 1.Davies S, Heyman I, Goodman R. A population survey of mental health problems in children with epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:292–5. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutter M, Graham P, Yule W. A neuropsychiatric study in childhood. Clin Dev Med. 1970:35–36. 1–265. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin JK, Harezlak J, Dunn DW, Huster GA, Rose DF, Ambrosius WT. Behavior problems in children before first recognized seizures. Pediatrics. 2001 Jan;107(1):115–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buelow JM, Austin JK, Perkins SM, Shen J, Dunn DW, Fastenau PS. Behavior and mental health problems in children with epilepsy and low IQ. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003 Oct;45(10):683–92. doi: 10.1017/S0012162203001270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones JE, Watson R, Sheth R, Caplan R, Koehn M, Seidenberg M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in children with new onset epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007 Jul;49(7):493–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oostrom K, van Teeseling H, Smeets-Schouten A, Peters A, Jennekens-Schinkel A. Childhood DSoEi. Three to four years after diagnosis: cognition and behaviour in children with ’epilepsy only’. A prospective, controlled study. Brain. 2005 July 1;128(7):1546–55. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn DW, Austin JK, Huster GA. Behaviour problems in children with new-onset epilepsy. Seizure. 1997 Aug;6(4):283–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin JK, Dunn DW, Caffrey HM, Perkins SM, Harezlak J, Rose DF. Recurrent seizures and behavior problems in children with first recognized seizures: A prospective study. Epilepsia. 2002;43(12):1564–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.26002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oostrom KJ, Schouten A, Kruitwagen CL, Peters AC, Jennekens-Schinkel A. Behavioral problems in children with newly diagnosed idiopathic or cryptogenic epilepsy attending normal schools are in majority not persistent. Epilepsia. 2003 Jan;44(1):97–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.18202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin JK, Caplan R. Behavioral and psychiatric comorbidities in pediatric epilepsy: toward an integrative model. Epilepsia. 2007 Sep;48(9):1639–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn D, Austin J, Caffrey H, Perkins S. A prospective study of teachers’ ratings of behavior problems in children with new-onset seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(1):26–35. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00642-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keene DL, Manion I, Whiting S, Belanger E, Brennan R, Jacob P, et al. A survey of behavior problems in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:581–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austin JK, Perkins SM, Johnson CS, Fastenau PS, Byars AW, deGrauw TJ, et al. Self-esteem and symptoms of depression in children with seizures: relationships with neuropsychological functioning and family variables over time. Epilepsia. 2010 Oct;51(10):2074–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodenburg R, Meijer AM, Dekovic M, Aldenkamp AP. Family factors and psychopathology in children with epilepsy: a literature review. Epilepsy Behav. 2005 Jun;6(4):488–503. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin JK, Dunn DW, Johnson CS, Perkins SM. Behavioral issues involving children and adolescents with epilepsy and the impact of their families: recent research data. Epilepsy Behav. 2004 Oct;5(Suppl 3):S33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CCT-ILAE. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. From the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1981;22:489–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1981.tb06159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CCT-ILAE. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1989 Jul-Aug;30(4):389–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byars AW, deGrauw TJ, Johnson CS, Fastenau PS, Perkins SM, Egelhoff JC, et al. The association of MRI findings and neuropsychological functioning after the first recognized seizure. Epilepsia. 2007 Jun;48(6):1067–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT) Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin JK, Fastenau PS. Are seizure variables related to cognitive and behavior problems? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010 Jan;52(1):5–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fastenau P, Johnson CS, Dunn DW, Byars AW, Perkins S, DeGrauw TJ, et al. Relationship between seizure control and neuropsychological change during the first 3 years following seizure onset in children. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 7) [Abstract] abstract 1.346. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wechsler D. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner R, Torgesen J, Rashotte C. Comprehensive test of phonological processing. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCubbin HI, Thompson AI. Family Stress Coping and Health Project. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 1991. Family assessment inventories for research and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smilkstein G. The Family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Prac. 1978;6:1231–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin JK, Huberty TJ. Revision of the Family APGAR for use by 8-year-olds. Fam Sys Med. 1989;7(3):323–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin JK, Shore CP, Dunn DW, Johnson CS, Buelow JM, Perkins SM. Development of the parent response to child illness (PRCI) scale. Epilepsy Behav. 2008 Nov;13(4):662–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piccinelli P, Beghi E, Borgatti R, Ferri M, Giordano L, Romeo A, et al. Neuropsychological and behavioural aspects in children and adolescents with idiopathic epilepsy at diagnosis and after 12 months of treatment. Seizure. 2010 Nov;19(9):540–6. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn D, Austin J, Harezlak J, Ambrosius W. ADHD and epilepsy in childhood. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003 Jan;45(1):50–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huberty TJ, Austin JK, Harezlak J, Dunn DW, Ambrosius WT. Informant Agreement in Behavior Ratings for Children with Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2000 Dec;1(6):427–35. doi: 10.1006/ebeh.2000.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodenburg R, Stams GJ, Meijer AM, Aldenkamp AP, Dekovic M. Psychopathology in children with epilepsy: A meta-analysis. J Ped Psychology. 2005;30(6):453–68. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caplan R, Siddarth P, Stahl L, Lanphier E, Vona P, Gurbani S, et al. Childhood absence epilepsy: Behavioral, cognitive, and linguistic comorbidities. Epilepsia. 2008;49(11):1838–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003 May;41(5):582–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailet LL, Turk WR. The impact of childhood epilepsy on neurocognitive and behavioral performance: A prospective longitudinal study. Epilepsia. 2000;41(4):426–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berg AT, Langfitt JT, Testa FM, Levy SR, DiMario F, Westerveld M, et al. Residual cognitive effects of uncomplicated idiopathic and cryptogenic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(4):614–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boelen S, Nieuwenhuis S, Steenbeek L, Veldwijk H, van de Ven-Verest M, Tan IY, et al. Effect of epilepsy on psychomotor function in children with uncomplicated epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:546–50. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205001064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diamond BJ, Johnson SK, Kaufman M, Graves L. Relationships between information processing, depression, fatigue and cognition in multiple sclerosis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008 Mar;23(2):189–99. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldenkamp AP, Arends J. Effects of epileptiform EEG discharges on cognitive function: is the concept of “transient cognitive impairment” still valid? Epilepsy Behav. 2004 Feb;5(Suppl 1):S25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fastenau PS, Johnson CS, Perkins SM, Byars AW, deGrauw TJ, Austin JK, et al. Neuropsychological status at seizure onset in children: risk factors for early cognitive deficits. Neurol. 2009 Aug 18;73(7):526–34. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b23551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oostrom KJ, Schouten A, Kruitwagen CLJJ, Peters ACB, Jennekens-Schinkel A. Parents’ perceptions of adversity introduced by upheaval and uncertainty at the onset of childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42(11):1452–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.14201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodenburg R, Marie Meijer A, Dekovic M, Aldenkamp AP. Family predictors of psychopathology in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47(3):601–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]