Abstract

The estrogen receptor α (ERα) is a master regulator of gene expression and works along with cooperating transcription factors in mediating the actions of the hormone estradiol (E2) in ER-positive tissues and breast tumors. Here, we report that expression of paired-like homeodomain transcription factor (PITX1), a tumor suppressor and member of the homeobox family of transcription factors, is robustly up-regulated by E2 in several ERα-positive breast cancer cell lines via ERα-dependent interaction between the proximal promoter and an enhancer region 5′ upstream of the PITX1 gene. Overexpression of PITX1 selectively inhibited the transcriptional activity of ERα and ERβ, while enhancing the activities of the glucocorticoid receptor and progesterone receptor. Reduction of PITX1 by small interfering RNA enhanced ERα-dependent transcriptional regulation of a subset of ERα target genes. The consensus PITX1 binding motif was found to be present in 28% of genome-wide ERα binding sites and was in close proximity to estrogen response elements in a subset of ERα binding sites, and E2 treatment enhanced PITX1 as well as ERα recruitment to these binding sites. These studies identify PITX1 as a new ERα transcriptional target that acts as a repressor to coordinate and fine tune target-specific, ERα-mediated transcriptional activity in human breast cancer cells.

Estrogens regulate gene expression in target cells, thereby controlling the development and optimal functioning of reproductive tissues and many nonreproductive tissues, such as bone. Estrogens, however, may also contribute to the growth and progression of breast and uterine cancers (1, 2). Estrogen receptor (ER) α, a ligand-inducible transcription factor, controls the stimulation and repression of specific gene expression in a signal-, tissue-, and promoter-specific fashion (3, 4).

Upon binding of 17β-estradiol (E2), the receptor changes conformation, resulting in dimerization and dissociation from inhibitory complexes, which enables ERα association with regulatory binding sites in the promoter and/or enhancer regions of target genes and the recruitment of coregulatory proteins, RNA polymerase II, and the basal transcriptional machinery that leads to regulation of target gene expression (5–8). Studies have now identified genome-wide binding sites for the nuclear receptor ERα in human breast cancer cells, and have also identified cooperating transcription factors the expression of which appears critical for ERα regulation of gene expression (9–16).

The paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 1 (PITX1) is present throughout pituitary development and regulates several pituitary-specific promoters (17). Despite PITX1 characterization in the pituitary and its cell lineages, the functions of PITX1 and its regulation outside the pituitary are not well understood. PITX1 is present in many tissues (18), and its expression is known to be critical for the development of the anterior pituitary gland and hind limb morphogenesis (19, 20). Initially identified as an activator of the pro-opiomelanocortin gene (21), PITX1 is now recognized to synergize with the transcription factors SF-1, Pit1, and the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors to regulate some genes in a promoter-specific manner in pituitary-derived cell types (22–25). PITX1 also has the ability to trans-repress the virus-induced interferon A promoter through interaction with the interferon-regulatory factors (IRF) 3 (IRF3) and 7 (IRF7) (26). Recent reports have shown PITX1 to suppress RAS activity through regulation of the RASAL gene, suggesting that PITX1 may also act as a tumor suppressor (18).

Here we report that PITX1 is under primary transcriptional control by ERα in breast cancer cells, and we show that its up-regulation involves a long-range interaction between a novel estrogen-responsive enhancer and the proximal promoter of PITX1. In addition, we demonstrate that PITX1 binds to ERα, is recruited along with ERα to a subset of ERα enhancers, and modulates the transcriptional activity of this nuclear receptor on ERα target genes that are enriched in PITX1 binding sites.

Results

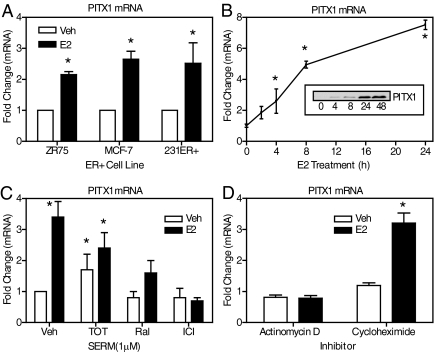

ERα-dependent regulation of PITX1 in breast cancer cells

Because our genome-wide cDNA microarray transcriptional profiling studies in ER-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells indicated that expression of the homeobox family member PITX1 was stimulated by treatment with the steroid hormone, E2 (27), we initiated studies to further explore ER regulation of PITX1 and its impact in breast cancer cells. Treatment of the ERα-positive ZR-75 and MCF-7 cells, and MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing the ERα (denoted 231ER+ cells) with 10 nm E2 for 4 h stimulated PITX1 mRNA 2- to 3-fold in all three cell lines (Fig. 1A). In time course studies, PITX1 mRNA was elevated by 2 h of E2 exposure, and levels continued to increase over the 24 h of E2 treatment (Fig. 1B). PITX1 protein was also increased after 4 h of 10 nm E2 treatment of 231ER+ cells and demonstrated a marked, maximal increase after 24–48 h of hormone treatment (Fig. 1B, inset). To determine the ability of the pure antiestrogen ICI 182,780 (ICI), and the selective ER modulators trans-hydroxytamoxifen (TOT) and raloxifene (Ral) to stimulate PITX1 mRNA and/or block E2 stimulation of PITX1 mRNA, we treated 231ER+ cells with 1 μm ICI, TOT, or Ral in the presence and absence of 10 nm E2. As shown in Fig. 1C, we observed no regulation of PITX1 mRNA by ICI or Ral alone (open bars), and both ligands antagonized the E2 stimulation of PITX1 mRNA (solid bars). By contrast, TOT functioned as a mixed agonist/antagonist. Treatment with TOT alone resulted in a weak stimulation of PITX1 mRNA, and TOT partially antagonized the E2-induced stimulation. The ligands showed similar effects on PITX1 mRNA expression in MCF-7 cells, where TOT was a mixed agonist/antagonist and Ral and ICI behaved as pure antagonists (27).

Fig. 1.

Up-regulation of PITX1 by estrogens in ERα-positive breast cancer cells. A, Quantitative PCR analysis of PITX1 mRNA expression in the ERα-positive cell lines ZR75, MCF-7, and 231ER+ cells treated with 0.1% ethanol vehicle or 10 nm E2 for 4 h. B, Quantitative PCR analysis for PITX1 mRNA stimulation in 231ER+ cells treated with 10 nm E2 for the times indicated. Inset, Western blot analysis of PITX1 protein in 231ER+ cells treated with 10 nm E2 for 0–48 h. C, Quantitative real-time PCR analysis for PITX1 mRNA in 231ER+ cells treated with either 1 μm TOT, 1 μm Ral, or 1 μm ICI alone or in combination with 10 nm E2 for 4 h. D, Real-time PCR analysis to determine whether actinomycin D (5 μm) or cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) can block E2 stimulation of PITX1 mRNA in 231ER+ cells. Cells were exposed to actinomycin D or cycloheximide for 1 h before addition of control vehicle or 10 nm E2 for 4 h in the continued presence of the inhibitor. Values are the mean from three independent experiments ± sem. *, P < 0.05 compared with 0 h or vehicle treatment. Veh, Vehicle.

We next examined whether PITX1 was under primary regulation by the ER and whether the E2 enhancement of PITX1 mRNA requires active transcription and/or new protein production. As shown in Fig. 1D, treatment of cells with the translational inhibitor cycloheximide did not abrogate the E2 stimulation of PITX1 mRNA, whereas the transcriptional inhibitor Actinomycin D completely blocked E2 stimulation. These results suggest that PITX1 mRNA is under primary transcriptional control by the receptor in several ERα-positive breast cancer cells.

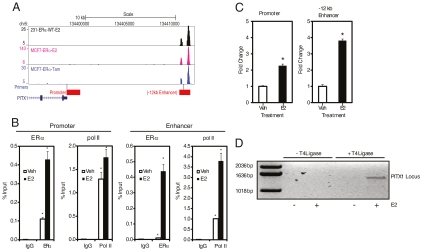

ERα regulation of PITX1 involves interaction of the ER-binding distal enhancer with the promoter of the PITX1 gene via intrachromosomal looping

Recent studies have identified genome-wide ER binding sites in MCF-7 and 231ER+ breast cancer cells treated with E2 (10, 13, 15, 16). Because PITX1 mRNA is stimulated by E2 and TOT (Fig. 1), we examined whether there was an ER binding site in proximity of the PITX1 gene in these genome-wide ERα binding datasets (15, 16), and we identified a strong binding site −12 kb upstream of the transcription start site of PITX1 in addition to a weak ERα binding site in the proximal promoter (Fig. 2A). The ER binding site located −12 kb upstream will herein be referred to as the PITX1 enhancer. ERα localized to this enhancer in the presence of E2 in 231ER+ cells and in the presence of both E2 and TOT in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2A). This PITX1 enhancer contains a full estrogen response element (ERE), GGGCACATTGACC, differing from the consensus ERE at only the one underlined position. PITX1 is the closest gene to this binding site and is therefore the most likely gene to be regulated by this ER binding site. To investigate this, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays (Fig. 2B) and observed that, at 45 min of E2 treatment, there was enhanced recruitment of both ERα and RNA polymerase II to the PITX1 enhancer. E2 also increased ERα presence at the PITX1 promoter, which contains only an ERE half-site, although RNA polymerase II recruitment at the promoter was minimally, if at all, increased by E2 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

E2 regulation of PITX1 involves communication between upstream and proximal ER binding sites. A, Genetic locus from the UCSC genome browser showing the natural 5′ to 3′ orientation of the PITX1 gene with the location of the identified ERα binding regions, the proximal promoter and enhancer, and the location of the primers used in ChIP and chromosome conformation capture experiments. B, ChIP assays for binding of ERα and RNA polymerase II (pol II) to the proximal promoter and −12 kb enhancer of PITX1 in MCF-7 cells treated with vehicle or 10 nm E2 for 45 min. Values show percent input and are representative of triplicate experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle treatment. C, Regulation of the PITX1 proximal promoter and −12 kb enhancer luciferase reporters in response to vehicle or 10 nm E2 treatment for 24 h in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with ERα. The regions cloned into the luciferase reporter construct are indicated as red blocks in panel A. *, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle treatment. D, Chromosome conformation capture assay examining the interaction between the proximal promoter and −12 kb enhancer of PITX1 in MCF-7 cells treated with vehicle or 10 nm E2 for 45 min. The locations of the primers used are indicated in panel A. Tam, Tamoxifen; Veh, vehicle.

We next determined whether the PITX1 enhancer and promoter regions were estrogen responsive by cloning these regions from genomic DNA into luciferase reporters, and we conducted transient transfection assays. The regions that were cloned are indicated as the red blocks in Fig. 2A and include 1000 bp immediately upstream of the transcription start site of the PITX1 gene for the promoter, and 600 bp surrounding the −12 kb ERα binding site for the enhancer. Estradiol treatment stimulated PITX1 enhancer activity 4-fold, while stimulating the PITX1 promoter 2-fold (Fig. 2C). These data demonstrate that ERα is recruited to and regulates both the identified PITX1 enhancer and promoter regions.

Even though ERα is recruited to the PITX1 enhancer and this enhancer is stimulated by E2, these observations do not conclusively demonstrate a role for this enhancer in PITX1 gene regulation by ERα. Therefore, to implicate this enhancer in receptor regulation of PITX1, we performed chromosome conformation capture experiments to determine whether ERα promotes chromosomal looping to bring the enhancer into close proximity with the promoter of PITX1 in E2-treated cells. Using the primers designated in Fig. 2A, we observed an E2 and T4 ligase-dependent PCR amplification of an approximately 1550-bp band, which is the predicted size based on the distance of the primers from the BamHI restriction enzyme cut sites. The identity of this DNA fragment was confirmed by DNA sequencing and demonstrated that approximately 10 kb of DNA was removed between the two joined genomic DNA fragments. E2-dependent looping was also observed in 231ER+ cells (data not shown). These data demonstrate an E2-ERα-induced interaction between the −12 kb enhancer and the proximal promoter of the PITX1 genomic locus.

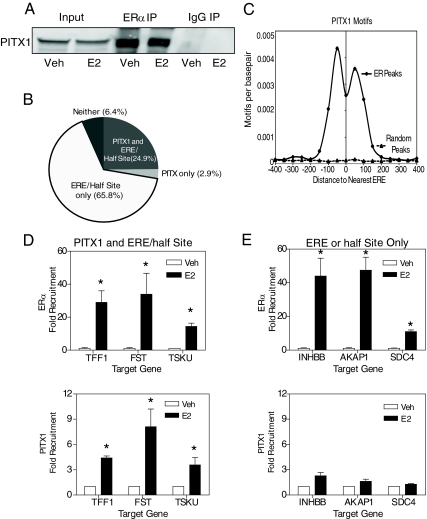

Presence of PITX1 binding motifs within ER binding sites

Previous studies have demonstrated that ERα and PITX1 synergize to regulate the LHβ gene (22). This prompted us to determine whether ERα and PITX1 interact in breast cancer cells. Coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed in MCF-7 cells and as seen in Fig. 3A, PITX1 interacted with ERα in immunoprecipitation assays but not with the IgG control. Interaction was consistently observed in the presence and absence of ligand in both MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3A) and in 231ER+ cells (data not shown), although the recruitment of PITX1 and ERα to chromatin binding sites and the regulation of gene expression was ligand dependent, as described below. Transcription is usually regulated by combinatorial usage of cooperating transcription factors in a signal- and promoter-specific manner (7). Recent genome-wide studies have shown that ER binding site regions in human breast cancer cells are enriched in binding sites for cooperating transcription factors, such as the forkhead factor FOXA1 (10, 13). We therefore examined whether the consensus PITX1 binding site, TAATCC, was enriched in genome-wide ER binding sites (Fig. 3B). We identified that 1798 (28%, P <2.2 × 10−16 relative to genomic background) of the 6472 ERα binding sites previously identified in 231ER+ cells (15) contain a consensus PITX1 motif. Of the total 6472 ER binding sites, 65.8% contained only an ERE or half-ERE site, 24.9% contained a PITX1 and ERE/half-ERE site, 3% contained only a PITX1 site, and 6.4% contained neither a PITX1 nor ERE/half-ERE site. This analysis suggests a potential role for PITX1 in modulating gene regulation mediated by approximately one fourth of ER binding sites (Fig. 3B). The distribution of PITX1 motifs in the ERα binding sites showed a strong colocalization near the putative ERE, with the majority of the PITX1 motifs residing within -/+ 100 bp of an ERE sequence (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

PITX1 motif enrichment in genome-wide ER binding sites. A, Coimmunoprecipitation assay for ERα and PITX1. MCF-7 cells were infected with adenovirus expressing full-length PITX1 for 24 h before 45-min control vehicle or 10 nm E2 treatment. Cells lysates were immunoprecipitated with either an ERα-specific antibody or IgG negative control. Western blot analysis was performed using a PITX1-specific antibody. B, Percentage of ERα binding sites that contain a consensus PITX1 binding motif or lack PITX1 motifs. C, Spatial distribution between the identified PITX1 motifs and EREs within random genomic sequences or ER binding peaks. D and E, Recruitment, monitored by ChIP, of ERα (top panels) and PITX1 (bottom panels) to ER binding sites that contain a consensus PITX1 binding site in vehicle and 10 nm E2-treated 231ER+ cells at 45 min (panel D) or to ER binding sites that lack a consensus PITX1 binding site in vehicle and 10 nm E2-treated 231ER+ cells at 45 min (panel E). *, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle treatment. IP, Immunoprecipitation; Veh, vehicle.

To better characterize the role of PITX1 in ERα-mediated gene regulation, we performed ChIP assays to examine the recruitment of ERα and PITX to ER binding sites containing both PITX1 and ERE/half-ERE sites, and for comparison, to ER binding sites with ERE/half-ERE sites but lacking a PITX1 binding site. As seen in Fig. 3D, E2 treatment of 231ER+ cells resulted in enhanced recruitment of both ERα and PITX1 to the trefoil factor 1 (TFF1) promoter, and also to the follistatin (FST) and Tsukushin enhancers, sites that contain both ERE/half-ERE sites and PITX1 binding sites. By contrast, treatment of cells with E2 increased the recruitment of ERα to the enhancer of inhibin β B, A-kinase anchor protein 1, and Syndecan 4, but, of note, E2 failed to stimulate recruitment of PITX1 to these ERα binding sites that lack PITX1 binding motifs (Fig. 3E). E2 treatment also promoted the recruitment of PITX1 to a subset of ERα binding sites that contain PITX1 motifs, but not ERE or half-EREs (data not shown).

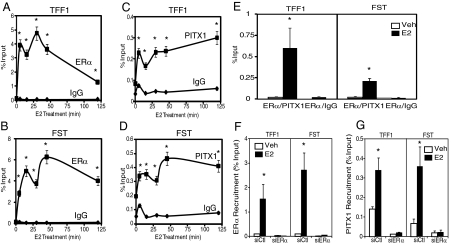

Further, ChIP time course experiments after E2 treatment revealed that both transcription factors were recruited rapidly and with similar time patterns of elevated recruitment at genes, such as TFF1 and FST that contain both ERα and PITX1 binding motifs (Fig. 4, A–D). To evaluate whether ERα and PITX1 are present in the same multiprotein complex at these gene sites, we performed ChIP/re-ChIP experiments after 45 min of E2 treatment by first immunoprecipitating using a PITX1 antibody followed by immunoprecipitating with an ERα antibody. This method isolates DNA where ERα and PITX1 are colocalized in the same complex. As shown in Fig. 4E, PITX1 and ERα were present together, in an E2-stimulated manner, at genes with ERα and PITX1 binding sites (i.e. TFF1 and FST). To determine whether PITX1 recruitment at ER binding sites was dependent on the presence of ERα, we conducted ChIP experiments in 231ER+ cells in which we knocked-down ERα using small interfering RNA (siRNA). As shown in Fig. 4, F and G, ERα knockdown was very efficient as demonstrated by the complete loss of recruitment of ERα after E2 treatment; and, more interestingly, the loss of ERα caused a concomitant loss of PITX1 recruitment at the TFF1 and FST ER binding sites, indicating that recruitment of PITX1 requires the presence of ERα.

Fig. 4.

Recruitment of ERα and PITX1 to binding sites of genes with both ERα and PITX binding motifs. A–D, Time course of ERα and PITX1 recruitment to two genes, TFF1 and FST, that contain both ERα and PITX1 binding sites, in response to 10 nm E2 treatment. ChIP assays were carried out at the times indicated with antibodies to ERα or PITX1, or with IgG as a negative control. *, P < 0.05 compared with corresponding IgG treatment. E, ChIP/reChIP analysis was conducted in MDA-MB-231ER+ cells to determine whether ERα and PITX1 are in the same complex. ChIP assays were first performed on 231ER+ cell lysates that were treated with vehicle or 10 nm E2 for 45 min and then with PITX1 antibody. The beads were washed extensively, and the complex was eluted from the beads. The sample was then immunoprecipitated with the ERα antibody or IgG. The DNA was isolated and quantified using quantitative real-time PCR. Data are presented as % Input and is mean ± range of two independent experiments. F, ChIP assays for ERα in 231ER+ cells after cells were transfected with ERα siRNA or control GL3 siRNA for 48 h before E2 or control vehicle treatment for 45 min. G, ChIP assays for PITX1 in 231ER+ cells treated with ERα siRNA or control (GL3) siRNA and control vehicle or E2 as in panel F. *, P < 0.05 compared with 0 h or vehicle treatment. Veh, Vehicle.

PITX1 inhibits ERα transcriptional activity, and this repression maps to the C-terminal region of PITX1

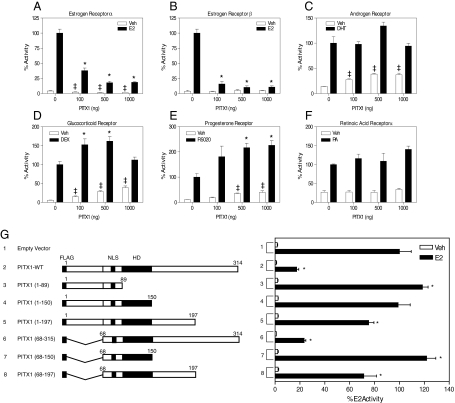

Based on the above observations, we examined the possibility that PITX1 might modulate ERα transcriptional activity. Transient transfections were performed in HEC-1 cells with ERα, the estrogen-responsive reporter 3xERE-luciferase, which contains both an ERE and PITX1 site, and increasing amounts of PITX1 expression vector. As seen in Fig. 5, A and B, increasing the level of PITX1 inhibited ERα and ERβ transcriptional activity in a dose-dependent manner. By contrast, PITX1 did not alter activity of the androgen receptor (Fig. 5C) or retinoic acid receptor (Fig. 5F), whereas it enhanced the activity of both the glucocorticoid receptor (Fig. 5D) and progesterone receptor (Fig. 5E). These data suggest that PITX1 specifically represses the transcriptional activity of ERα and ERβ but can enhance the activities of other nuclear receptors, such as glucocorticoid receptor and progesterone receptor.

Fig. 5.

Effect of PITX1 on the transcriptional activity of different nuclear hormone receptors and analysis of the regions of PITX1 important for its repression of ERα activity. HEC1 cells were transfected with ERα and a 3ERE-luciferase reporter (panel A), ERβ and a 3ERE-luciferase reporter (panel B), AR and a 2PRE-luciferase reporter (panel C), GR and a 2PRE-luciferase reporter (panel D), PRB and a 2PRE-luciferase reporter (panel E), or RARα and a RARE-luciferase reporter (panel F). Transfections also included increasing amounts of pSPORT6-PITX1 (0, 100, 500, or 1000 ng). G, Schematic of wild type PITX1 and PITX1 truncation mutants used. NLS, Nuclear localization sequence; HD, Homeodomain. HEC-1 cells were transfected with pCMV5-ERα, pTAG-2B-PITX1, and the 3ERE-luciferase reporter vector. All transfections (panels A–G) contained a β-galactosidase internal control reporter to normalize for transfection efficiency. Cells were treated with vehicle or 10 nm of the corresponding receptor ligand. Values show the percent activity from triplicate experiments ± sem. *, P < 0.05 compared with 100% activity (no added PITX1). ‡, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle-treated 0 ng PITX1 samples. DEX, Dexamethasone; RA, retinoic acid; Veh, vehicle.

To determine the domains of PITX1 responsible for PITX1 trans-repression of ERα, we created N-terminal and C-terminal truncations of PITX1 and assessed their ability to repress ERα-mediated transcription (Fig. 5G). Estradiol stimulated the ERE-driven luciferase reporter gene approximately 30-fold (entry 1), and addition of full-length PITX1 blocked the ability of E2-ERα to stimulate transcription by greater than 80% (Fig. 5G, entry 2 vs.1). Deletion of the first 67 amino acids of PITX1 had no significant effect on repression of ERα-mediated transcription, because PITX1 (68–314, entry 6) retained full ability to suppress ER. Interestingly, deletion of the last 118 amino acids of PITX1 (PITX 1-197, entry 5) or further deletions in from the C terminus of PITX1 (entries 3, 4, and 7) resulted in loss of PITX1-dependent repression of ERα, indicating that the C-terminal region (amino acids 151-304) is required for the observed repression (Fig. 5G).

PITX1 controls the expression of select ER target genes

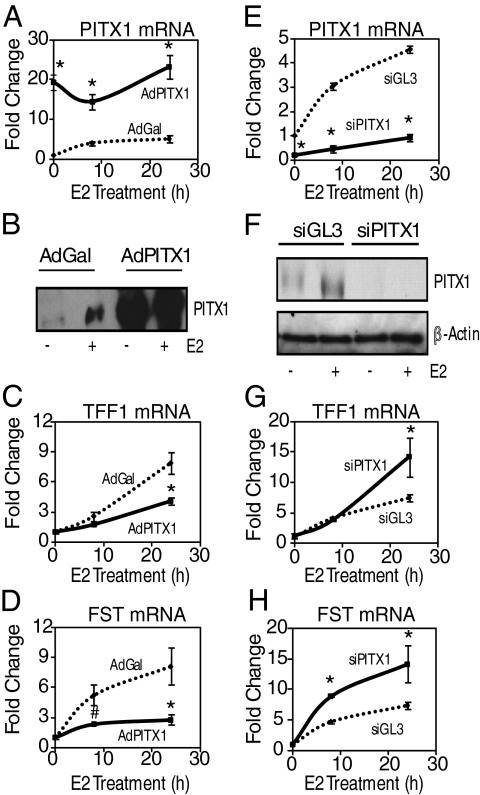

The observation that PITX1 repressed ER activity on an ER-responsive reporter construct (Fig. 5) suggested that PITX1 might modulate the ability of ERα to regulate endogenous gene expression in breast cancer cells. Therefore, the ability of ERα to regulate gene expression was assessed in the presence of reduced or increased PITX1, using siRNA knock down or adenovirus-mediated overexpression of PITX1. The use of adenovirus-expressing PITX1 greatly increased the intracellular levels of PITX1 mRNA and protein (Fig. 6, A and B), which resulted in a blunted E2-stimulated response for both TFF1 and FST mRNA (Fig. 6, C and D). When PITX1 mRNA was reduced by PITX1 siRNA (by >80%) and the PITX1 protein became no longer detectable in 231ER+ cells compared with the control (siGL3 luciferase)-treated cells (Fig. 6, E and F), we found that this knockdown of PITX1 resulted in a hyperstimulation of both TFF1 and FST mRNA by E2 (Fig. 6, G and F). PITX1 siRNA did not affect ERα expression (data not shown). Interestingly, modulation of PITX1 cellular levels by either siRNA or adenovirus overexpression did not affect the E2 regulation for genes containing ER binding sites that lack the consensus PITX1-binding motif (data not shown). Collectively these results demonstrate that PITX1 functions to repress ERα transcriptional activity on a subset of target genes in breast cancer cells.

Fig. 6.

PITX1 regulates the expression of ERα target genes. A, Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of PITX1 mRNA in 231ER+ cells treated with AdGal or AdPITX1 for 24 h before 10 nm E2 treatment for the times indicated. *, P < 0.05 compared with corresponding AdGal E2 treatment. B, Western blot analysis for PITX1 protein levels in 231ER+ cells infected with adenovirus expressing either β-gal or PITX1 and treated with vehicle or 10 nm E2 for 45 min. Quantitative real-time PCR for TFF1 mRNA (panel C) or FST mRNA (panel D) in 231ER+ cells treated with AdGal or AdPITX1 for 24 h before 10 nm E2 treatment for the times indicated. *, P < 0.05; #, P < 0.1 compared with corresponding AdGal E2 treatment. E, Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of PITX1 mRNA in 231ER+ cells treated with siGL3 or siPITX1 for 48 h before 10 nm E2 treatment for times indicated. *, P < 0.05 compared with corresponding siGL3 E2 treatment. F, Western blot analysis for PITX1 or β-actin protein levels in 231ER+ cells transfected with siRNA targeting either GL3 luciferase or PITX1 and treated with vehicle or 10 nm E2. Quantitative real-time PCR for TFF1 mRNA (panel G) or FST mRNA (panel H) in 231ER+ cells treated with siGL3 or siPITX1 for 48 h before 10 nm E2 treatment for the times indicated. *, P < 0.05; #, P < 0.1 compared with corresponding siGL3 E2 treatment.

Discussion

In the present studies we have identified PITX1 as a novel transcriptional target of the ER in several ERα-positive breast cancer cells and show that this up-regulation of PITX1 gene expression involves hormone-induced interaction between proximal and long-distance ERα binding sites. We further show that ERα and PITX1 interact, and we have defined a novel function of PITX1 as a selective repressor that modulates the transcriptional activity of ERα target genes that have ER-binding sites containing PITX1-binding motifs.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of hormonal regulation of PITX1 expression. PITX1 regulation by ERα appears to be a primary transcriptional response in which estradiol induces ERα-dependent interaction between the proximal promoter and 5′-upstream enhancer ERα binding sites of the PITX1 gene. Long-distance gene regulation by the ERα has been highlighted by recent genome-wide identification of ER binding sites (10, 13). These studies have concluded that the majority of ERα binding sites are located further than 5 kb from the transcriptional start site of E2-regulated genes (10, 13, 15, 16) and that regulation by ERα often involves the interaction of multiple ER binding sites located far apart (28–30). These findings are consistent with the involvement of an enhancer approximately 12 kb upstream of the PITX1 transcription start site in the long-range transcriptional control of PITX1 gene regulation by ERα that we have observed.

Transcriptional control of gene expression by ERα can be by binding to DNA at EREs or through indirect interaction of the receptor with DNA via transcription factors such as Sp1 and activator protein 1 (15). Using bioinformatic approaches, we observed that 28% of the genome-wide ERα binding sites also contain a PITX1-binding motif, which supports the hypothesis that PITX1 may be a cooperating factor for ERα, coordinating estrogen-mediated transcriptional control of a subset of ERα target genes. Examination of the distribution of these PITX1 sites showed that they are mostly enriched in close proximity to EREs. Consistent with the bioinformatic analyses, we observed hormone-stimulated and ERα-dependent recruitment of PITX1 only to ER binding sites that contain consensus PITX1 binding sites.

There is good evidence that ERα and other nuclear receptors change chromatin architecture and can poise chromatin in a manner that facilitates recruitment of cooperating cofactors (31, 32). Because E2 treatment increases the level of PITX1, and ERα and PITX1 bind to one another, ERα binding to its genomic sites in target genes could facilitate PITX1 recruitment to nearby PITX1 binding sites. Studies by others have identified the DNA response element for FOXA1, a forkhead factor, to be enriched in ERα binding sites and have defined a role for FOXA1 as a pioneer factor the function of which is to poise chromatin to facilitate recruitment of ERα to these binding sites, thus directing the regulation of target genes (9–11).

Increasing the intracellular level of PITX1 selectively inhibited the transcriptional activity of ERα and ERβ on reporter genes, whereas PITX1 had no repressive effect on four other nuclear receptors that were assessed. In fact, PITX1 increased the activity of progesterone receptor and glucocorticoid receptor, both in the absence and presence of their respective ligands, whereas no change was observed in the activity of the retinoic acid receptor α. Our study of truncated forms of PITX1 indicated that the C-terminal portion of the protein, amino acids 197–314, as well as the region of amino acids 150–197, was needed for this repression. Interestingly, amino acids 150–197 of PITX1 were shown previously to be necessary for PITX1 repression of IRF3 and IRF7 (26); therefore, this region of PITX1 might contain an intrinsic repression domain responsible for PITX1 repression of several interacting transcription factors, now including the nuclear hormone receptor ERα.

We demonstrate here several levels of cross-talk between PITX1 and ERα. PITX1 gene expression is up-regulated by estradiol via ERα, and PITX1 also interacts with ERα to suppress ERα transcriptional activity on a subset of ERα target genes. It would be of interest in future experiments to determine whether PITX1 directly recruits corepressor complexes to these ERα-binding sites, or whether PITX1 along with its known binding partner Brg1 (32) might modify the epigenetic landscape of these ERα binding sites resulting in the dampening of ERα transcriptional activity.

Our studies have identified a novel role for PITX1 in modulating the transcriptional activity of ERα in breast cancer cells. However, the biological impact of PITX1 in breast tumors or other estradiol-responsive tumors remains unknown. Genome-wide mRNA profiling of human tumor samples, documented in the Oncomine database, indicates that PITX1 mRNA is significantly overexpressed in ductal breast carcinomas (P < 2.7 × 10−9) (33) compared with normal breast, but is significantly underexpressed in mucinous breast carcinomas (P < 0.002) (34), ovarian cystadenocarcinomas (P < 0.01) (34), and prostate carcinomas (P < 0.008 and P < 0.04) (35, 36). Therefore, PITX1 expression is altered in several types of E2-responsive tumors, which might affect the functional activities of ERα in these tumors. Collectively, our findings that PITX1 is up-regulated by E2 in ERα-containing breast cancer cells and that PITX1 modulates ERα-dependent transcriptional activity suggest that the altered expression (overexpression or underexpression) of PITX1 in different types of breast cancers and in some ovarian and prostate cancers compared with their normal tissue counterparts, might affect the development and/or progression and phenotypic properties of these tumors. Future investigations in human tumor specimens should provide further insights into the role of this transcription factor in breast cancer and other cancers in which ERα has important biological activities.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and transient transfection assays

MCF-7 cells, and MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing ERα, were grown as previously described (37–39). Cells were switched 4 d before treatment to phenol red-free tissue culture medium containing 5% charcoal-dextran-treated calf serum. Medium was changed on d 2 and d 4 of culture after which cells were treated with control 0.1% ethanol vehicle, 10 nm E2, or 1 μm antiestrogen alone or with 10 nm E2 for the various times indicated.

Some transfections were done in ER-negative MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells or human endometrial cancer HEC-1 cells that were maintained as previously described (37, 40). The cells were plated in 24-well plates and transfected when approximately 80% confluent. Transfections were performed using 0.5 μg of the 3ERE-luciferase, 0.5 μg 2PRE-TK-luc, 0.5 μg of RARE-luc, or pGL3-control construct, 0.2 μg of the internal reference ß-galactosidase reporter plasmid pCMV5-ß-gal, 0.1 μg ER expression vector, and various concentrations of pSport6-PITX1. A premix containing 5 μl/well lipofectin, 1.6 μg/well transferrin, and 54 μl/well Hank's balanced salt solution was mixed with DNA in Hank's balanced salt solution (75 μl/well) for 15 min at room temperature. The cells were washed with serum-free medium, after which the liquid was aspirated and replaced with 300 μl serum-free media/well. A total of 150 μl of the DNA/lipofectin/transferrin mixture (75 μl DNA and 75 μl lipofectin/transferrin mixture) was added to each well. After incubation for 8 h at 37 C in a 5% CO2 incubator, the cells were washed once with medium containing 5% charcoal dextran-treated calf serum and then replaced with 1 ml medium plus serum. Cells were treated with the indicated ligand or 0.1% ethanol control for 24 h at 37 C, and cell lysates were then harvested using reporter lysis buffer (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) and analyzed using the Luciferase Assay system (Promega) on a MLX Microtiter Plate Luminometer (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was reverse transcribed, and real-time PCR was performed exactly as described elsewhere (39). The fold-change in expression for each gene was calculated as described previously, with the ribosomal protein 36B4 mRNA as an internal control. Real-time PCR of ChIP samples was performed in a similar manner with appropriate primers and data normalized to percent input.

Western blot analysis

Cell protein lysates were separated in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were incubated in blocking buffer (5% milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.5% Tween) and then with specific antibodies for ERα (HC20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), PITX1 (A300–577A; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), and β-actin (AC-15; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), followed by detection using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies with Supersignal West Femto Detection Kit (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL), as described by the manufacturer.

Chromosome conformation capture assays

MCF-7 and 231ER+ cells were treated with vehicle or 10 nm E2 for 45 min and fixed in 2% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. The formaldehyde was quenched with addition of 0.125 m glycine, and cells were lysed in lysis buffer [10 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 10 mm NaCl, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 1X Complete Protease Inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN)] at 4 C for 90 min. The nuclei were resuspended in 1X New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) Buffer 2 and 0.3% SDS and incubated at 37 C for 60 min while rotating. Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1.8% to sequester the SDS and incubated at 37 C for 60 min with gentle rotation. The chromatin was then digested overnight using MseI (New England Biolabs) or BamHI (New England Biolabs) at 37 C with gentle rotation. SDS was added to a final volume of 1.6%, and the samples were heated at 65 C for 20 min. Two aliquots of the chromatin samples (2 μg) were diluted in ligation buffer containing 1% Triton-X and incubated at 37 C for 1 h. The temperature was lowered to 16 C, and T4 Ligase (New England Biolabs) was added and samples were incubated overnight. The ligated DNA was purified using phenol/chloroform extraction and analyzed using PCR amplification. Resulting PCR products were sequenced and mapped back to the UCSC Genome Browser for verification.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays

MCF-7 cells were infected with adenovirus containing the full-length PITX1 cDNA (AdPITX1) for 24 h. Cells were then treated with vehicle control or 10 nm E2 for 45 min before cell lysate collection. The lysate was cleared of insoluble material after sonication and centrifugation, precleared with protein A/G agarose beads, and then subjected to immunoprecipitation using ERα (F-10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or IgG control antibodies. The immunoprecipitated complexes were collected using protein A/G agarose beads, washed four times with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer, and eluted. Eluates were separated in SDS polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were incubated in LI-COR blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and then with PITX1 (A300–577A, Bethyl Laboratories) antibody, followed by detection using IRDye secondary antibody (LI-COR Biosciences).

ChIP assays

Assays were performed essentially as described previously (41) with a few noted modifications (28). The antibodies used in these studies were: ERα, HC-20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); RNA polymerase II, N-20 (Santa Cruz); PITX1, A300-577A (Bethyl Laboratories). For PCR, 1 μl from a 50 μl DNA extraction was quantified using quantitative real-time PCR. ChIP-reChIP experiments were performed using PITX1 antibody for the first pulldown, followed by extensive washes and elution using 10 mm dithiothreitol for 30 min at 37 C. The eluate was diluted in immunoprecipitation buffer, and a second pulldown was performed with ERα antibody or IgG as control. The washes, elution, DNA recovery, and analysis were done as for ChIP assays.

siRNA and overexpression studies

MDA-MB-231ER+ cells were plated in phenol red-free medium containing 5% charcoal-dextran-treated calf serum at 250,000 cells per well in six-well plates, and transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions as described previously (42). Synthetic RNA oligonucleotides targeting PITX1 and control (GL3) luciferase were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). The siRNA target sequences used were: PITX1 NNGCAACGTACGCACTTCACA; GL3 target sequences were obtained from Dharmacon (catalog no. D-001400-01). siRNA was used at 20 nm, as recommended by the manufacturer, and cells were exposed to the siRNA for 72 h and then treated with control vehicle or hormone for the times indicated.

For PITX1 overexpression studies, adenovirus containing full-length PITX1 (AdPITX1) was prepared using the AdEasy System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. As a control, adenovirus containing the β-galactosidase gene (AdGal) was prepared in parallel. The viruses were amplified and isolated from AD-293 cells as recommended.

Bioinformatic analysis for PITX1 binding site enrichment

The genome-wide ERα binding site database established in 231ER+ cells (15) was searched for the presence of the consensus PITX1 binding site, TAATCC. For comparison, 1,000,000 random DNA sequences from the human genome (hg18), each consisting of 1000 bp, were also searched for the presence of PITX1 binding sites. The P value for PITX1 enrichment in the ER binding sites was generated using the hypergeometric distribution test (43). The ERα binding sites were centered on the position of the ERE, and the moving averages of PITX1 motif frequency were plotted in relation to distance to the nearest ERE.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant P50 AT006268 from Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS), The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), and National Cancer Institute (to B.S.K.), a grant from The Breast Cancer Research Foundation (to B.S.K.), and NIH Training Grants NIH T32 HD07028 (to J.D.S. and D.H.B.) and ES07328 (to C.C.F.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ChIP

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- E2

- estradiol

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- ERE

- estrogen response element

- FST

- follistatin

- ICI

- ICI 182,780

- IRF

- interferon-regulatory factor

- PITX1

- paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 1

- Ral

- raloxifene

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- SDS

- sodium dodecyl sulfate

- TFF1

- trefoil factor 1

- TOT

- trans-hydroxytamoxifen.

References

- 1. Couse JF, Korach KS. 1999. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev 20:358–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deroo BJ, Korach KS. 2006. Estrogen receptors and human disease. J Clin Invest 116:561–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. 2002. Biomedicine. Defining the “S” in SERMs. Science 295:2380–2381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katzenellenbogen BS, Montano MM, Ediger TR, Sun J, Ekena K, Lazennec G, Martini PG, McInerney EM, Delage-Mourroux R, Weis K, Katzenellenbogen JA. 2000. Estrogen receptors: selective ligands, partners, and distinctive pharmacology. Recent Prog Horm Res 55:163–193; discussion 194–195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hall JM, Couse JF, Korach KS. 2001. The multifaceted mechanisms of estradiol and estrogen receptor signaling. J Biol Chem 276:36869–36872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. 2002. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell 108:465–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosenfeld MG, Lunyak VV, Glass CK. 2006. Sensors and signals: a coactivator/corepressor/epigenetic code for integrating signal- dependent programs of transcriptional response. Genes Dev 20:1405–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanchez R, Nguyen D, Rocha W, White JH, Mader S. 2002. Diversity in the mechanisms of gene regulation by estrogen receptors. Bioessays 24:244–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brodsky AS, Li W, Meyer CA, Szary AJ, Eeckhoute J, Shao W, Hestermann EV, Geistlinger TR, Fox EA, Silver PA, Brown M. 2005. Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell 122:33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carroll JS, Meyer CA, Song J, Li W, Geistlinger TR, Eeckhoute J, Brodsky AS, Keeton EK, Fertuck KC, Hall GF, Wang Q, Bekiranov S, Sementchenko V, Fox EA, Silver PA, Gingeras TR, Liu XS, Brown M. 2006. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genet 38:1289–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eeckhoute J, Carroll JS, Geistlinger TR, Torres-Arzayus MI, Brown M. 2006. A cell-type-specific transcriptional network required for estrogen regulation of cyclin D1 and cell cycle progression in breast cancer. Genes Dev 20:2513–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Laganière J, Deblois G, Lefebvre C, Bataille AR, Robert F, Giguère V. 2005. Location analysis of estrogen receptor α target promoters reveals that FOXA1 defines a domain of the estrogen response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:11651–11656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin CY, Vega VB, Thomsen JS, Zhang T, Kong SL, Xie M, Chiu KP, Lipovich L, Barnett DH, Stossi F, Yeo A, George J, Kuznetsov VA, Lee YK, Charn TH, Palanisamy N, Miller LD, Cheung E, Katzenellenbogen BS, Ruan Y, Bourque G, Wei CL, Liu ET. 2007. Whole-genome cartography of estrogen receptor α binding sites. PLoS Genet 3:e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Madak-Erdogan Z, Lupien M, Stossi F, Brown M, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2011. Genomic collaboration of estrogen receptor α and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 in regulating gene and proliferation programs. Mol Cell Biol 31:226–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stender JD, Kim K, Charn TH, Komm B, Chang KC, Kraus WL, Benner C, Glass CK, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2010. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor α DNA binding and tethering mechanisms identifies Runx1 as a novel tethering factor in receptor-mediated transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol 30:3943–3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Welboren WJ, van Driel MA, Janssen-Megens EM, van Heeringen SJ, Sweep FC, Span PN, Stunnenberg HG. 2009. ChIP-Seq of ERα and RNA polymerase II defines genes differentially responding to ligands. EMBO J 28:1418–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tremblay JJ, Lanctôt C, Drouin J. 1998. The pan-pituitary activator of transcription, Ptx1 (pituitary homeobox 1), acts in synergy with SF-1 and Pit1 and is an upstream regulator of the Lim-homeodomain gene Lim3/Lhx3. Mol Endocrinol 12:428–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kolfschoten IG, van Leeuwen B, Berns K, Mullenders J, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R, Voorhoeve PM, Agami R. 2005. A genetic screen identifies PITX1 as a suppressor of RAS activity and tumorigenicity. Cell 121:849–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Szeto DP, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Ryan AK, O'Connell SM, Liu F, Kioussi C, Gleiberman AS, Izpisúa-Belmonte JC, Rosenfeld MG. 1999. Role of the Bicoid-related homeodomain factor Pitx1 in specifying hindlimb morphogenesis and pituitary development. Genes Dev 13:484–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Szeto DP, Ryan AK, O'Connell SM, Rosenfeld MG. 1996. P-OTX: a PIT-1-interacting homeodomain factor expressed during anterior pituitary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:7706–7710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lamonerie T, Tremblay JJ, Lanctôt C, Therrien M, Gauthier Y, Drouin J. 1996. Ptx1, a bicoid-related homeo box transcription factor involved in transcription of the pro-opiomelanocortin gene. Genes Dev 10:1284–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luo M, Koh M, Feng J, Wu Q, Melamed P. 2005. Cross talk in hormonally regulated gene transcription through induction of estrogen receptor ubiquitylation. Mol Cell Biol 25:7386–7398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melamed P, Koh M, Preklathan P, Bei L, Hew C. 2002. Multiple mechanisms for Pitx-1 transactivation of a luteinizing hormone β subunit gene. J Biol Chem 277:26200–26207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poulin G, Lebel M, Chamberland M, Paradis FW, Drouin J. 2000. Specific protein-protein interaction between basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors and homeoproteins of the Pitx family. Mol Cell Biol 20:4826–4837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tremblay JJ, Marcil A, Gauthier Y, Drouin J. 1999. Ptx1 regulates SF-1 activity by an interaction that mimics the role of the ligand-binding domain. EMBO J 18:3431–3441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Island ML, Mesplede T, Darracq N, Bandu MT, Christeff N, Djian P, Drouin J, Navarro S. 2002. Repression by homeoprotein pitx1 of virus-induced interferon a promoters is mediated by physical interaction and trans repression of IRF3 and IRF7. Mol Cell Biol 22:7120–7133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frasor J, Stossi F, Danes JM, Komm B, Lyttle CR, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2004. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: discrimination of agonistic versus antagonistic activities by gene expression profiling in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 64:1522–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barnett DH, Sheng S, Charn TH, Waheed A, Sly WS, Lin CY, Liu ET, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2008. Estrogen receptor regulation of carbonic anhydrase XII through a distal enhancer in breast cancer. Cancer Res 68:3505–3515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deschênes J, Bourdeau V, White JH, Mader S. 2007. Regulation of GREB1 transcription by estrogen receptor α through a multipartite enhancer spread over 20 kb of upstream flanking sequences. J Biol Chem 282:17335–17539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fullwood MJ, Liu MH, Pan YF, Liu J, Xu H, Mohamed YB, Orlov YL, Velkov S, Ho A, Mei PH, Chew EG, Huang PY, Welboren WJ, Han Y, Ooi HS, Ariyaratne PN, Vega VB, Luo Y, Tan PY, Choy PY, Wansa KD, Zhao B, Lim KS, Leow SC, Yow JS, et al. 2009. An oestrogen-receptor-α-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature 462:58–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. He HH, Meyer CA, Shin H, Bailey ST, Wei G, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Xu K, Ni M, Lupien M, Mieczkowski P, Lieb JD, Zhao K, Brown M, Liu XS. 2010. Nucleosome dynamics define transcriptional enhancers. Nat Genet 42:343–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lupien M, Eeckhoute J, Meyer CA, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Li W, Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brown M. 2008. FoxA1 translates epigenetic signatures into enhancer-driven lineage-specific transcription. Cell 132:958–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richardson AL, Wang ZC, De Nicolo A, Lu X, Brown M, Miron A, Liao X, Iglehart JD, Livingston DM, Ganesan S. 2006. X chromosomal abnormalities in basal-like human breast cancer. Cancer Cell 9:121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, Barrette T, Pandey A, Chinnaiyan AM. 2004. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia 6:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luo JH, Yu YP, Cieply K, Lin F, Deflavia P, Dhir R, Finkelstein S, Michalopoulos G, Becich M. 2002. Gene expression analysis of prostate cancers. Mol Carcinog 33:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Magee JA, Araki T, Patil S, Ehrig T, True L, Humphrey PA, Catalona WJ, Watson MA, Milbrandt J. 2001. Expression profiling reveals hepsin overexpression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 61:5692–5696 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ediger TR, Kraus WL, Weinman EJ, Katzenellenbogen BS. 1999. Estrogen receptor regulation of the Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factor. Endocrinology 140:2976–2982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Frasor J, Danes JM, Komm B, Chang KC, Lyttle CR, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2003. Profiling of estrogen up- and down-regulated gene expression in human breast cancer cells: insights into gene networks and pathways underlying estrogenic control of proliferation and cell phenotype. Endocrinology 144:4562–4574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stender JD, Frasor J, Komm B, Chang KC, Kraus WL, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2007. Estrogen-regulated gene networks in human breast cancer cells: involvement of E2F1 in the regulation of cell proliferation. Mol Endocrinol 21:2112–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rajendran RR, Nye AC, Frasor J, Balsara RD, Martini PG, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2003. Regulation of nuclear receptor transcriptional activity by a novel DEAD box RNA helicase (DP97). J Biol Chem 278:4628–4638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. 2000. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell 103:843–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frasor J, Danes JM, Funk CC, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2005. Estrogen down-regulation of the corepressor N-CoR: mechanism and implications for estrogen derepression of N-CoR-regulated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:13153–13157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. 2010. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 38:576–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]