Abstract

Over the last decade, our understanding of helper/effector T cell differentiation has changed dramatically. The discovery of interleukin (IL-)17–producing T cells (Th17) and other subsets has changed our view of T cell-mediated immunity. Characterization of the signaling pathways involved in the Th17 commitment has provided exciting new insights into the differentiation of CD4+ T cells. Importantly, the emerging data on conversion among polarized T helper cells have raised the question how we should view such concepts as T cell lineage commitment, terminal differentiation and plasticity. In this review, we will discuss the current understanding of the signaling pathways, molecular interactions, and transcriptional and epigenetic events that contribute to Th17 differentiation and acquisition of effector functions.

Keywords: Th17, T cell differentiation, cytokines, signal transduction, transcription factor, epigenetics

1. Introduction

The selective production of cytokines by subsets of CD4+ T cells is a major mode of immunoregulation and an important mechanism by which CD4+ T cells orchestrate immune responses. Activated CD4+ T cells can be subdivided into lineages on the basis of the cytokines that they secrete, the specific transcription factors that they express and the immunological function that they mediate. CD4+ T helper (Th) cells were initially viewed as having two possible fates, Th1 and Th2 cells [1, 2]. Th1 cells, which express the transcription factor T-bet and secrete IFN-γ, protect the host against intracellular infections including viruses and Toxoplasma [3]. In contrast, Th2 cells, which express GATA-3 and secrete interleukin (IL-)4, IL-5 and IL-13, mediate host defense against helminths [4]. Recently, these two classical lineages have been joined by additional subsets that preferentially produce distinct cytokines. One includes cells that selectively produce IL-17 (Th17 cells) [5][6][7][8][9][10]. These cells are critical for host defense against extracellular pathogens [11] and have been implicated in a number of autoimmune diseases [12][13][14][15][16][17]. Th17 cells can also produce IL-9, IL-10, IL-21, and IL-22; however, subsets of cells that selectively produce these cytokines have also been identified [18][19][20][21]. The other major lineage of CD4+ T cells includes those that express the transcription factor Foxp3. These immunosuppressive, regulatory T (Treg) cells comprise both natural (n)Tregs and induced (i)Tregs [22][23][24].

In this review, we examine the major factors that promote Th17 cell differentiation and discuss the signaling pathways and transcription factors that drive specification of this lineage. We then discuss how these factors influence epigenetic modifications of the Il17 locus and the extent to which can influence stability versus plasticity of this subset. Finally, we will briefly review the relationship between the selective production of IL-17 and other cytokines and examine how this relates to lineage commitment versus flexibility of phenotype.

2. T cell receptor (TCR) signaling and IL-17 production

An obligate first step in the activation of CD4+ T cells is engagement of the T cell receptor. Not surprisingly, this is an important contributor to IL-17 regulation and for invariant NK T cells and γδT cells, TCR engagement is sufficient [25, 26]. For naïve CD4+ T cells, the “strength” of TCR signaling as determined by the concentration of cognate antigen is an important driver of Th1 versus Th2 differentiation [27]. Precisely how signal strength influences IL-17 regulation is also incompletely understood. Recently it has been found that high dose antigen-loaded dendritic cells induce Th17 generation [28]. The Tec family tyrosine kinase inducible T cell kinase (Itk) is a tyrosine kinase required for full TCR-induced phosholipase C-γ activation [29]. Itk−/− mice show decreased IL-17 production [30]. Similarly, Raftlin, a protein located in lipid rafts, has been suggested to regulate the strength of TCR signaling [31]. Raftlin−/− T cells produce less IL-17 and Raftlin−/− mice show reduced severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [31]. Similarly, an E3 ubiquitin ligase denoted GRAIL (Gene related to anergy in lymphocytes) which regulates TCR-CD3 degradation, also influences IL-17 production [32]. These results are puzzling insofar as “strong” signals typically induce T-bet expression and Th1 differentiation. In human CD4+ T cells, it has been shown that “weak” TCR stimulation promoted Th17 responses [33]. It might be expected that upregulation of T-bet could attenuate IL-17 production. Recent work has revealed that mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 2 (mTORC2) impaired differentiation into Th1 and Th2 cells without significant effect on Th17 differentiation [34]. Clearly more work is required in this area.

Signals from co-stimulatory molecules are also important for helper cell specification. But it is still controversial for Th17 differentiation; both ICOS and CD28 activation have been implicated in Th17 differentiation [6]. ICOS−/− mice have exaggerated severity of Th17-mediated encephalomyelitis [35], while ICOS−/− CD4+ T cells show no significant increase of IL-17 production in vitro [36]. More work is required in this area.

3. Role of cytokines in Th17 differentiation

Initial views of specification

IL-23 is a heterodimeric cytokine composed of p19 and p40, the latter subunit being shared with IL-12 [37]. IL-23 has long been recognized to be an inducer of IL-17 [38]. Moreover, gene targeting of p19 dramatically attenuated EAE, a disease that is dominated by Th cells that produce IL-17 [39]. However, more recently it has been appreciated that naïve T cells do not express the IL-23R [9, 15]. Rather, it needs to be induced. This has led to the notion that IL-23 cannot be the sole inducer of Th17 differentiation. Other cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-21 are implicated in the regulation/induction of IL-17 production [15, 38, 40] [41]. In vitro, IL-6 is a potent inducer of Th17 cells but only when combined with other cytokines including transforming growth factor β 1 (TGF-β1) [42][7, 8]. This led to the finding that the conjunction of TGF-β1 with IL-6 is the initial driver of Th17 specification[7]. However, IL-6−/− mice have reduced but not absent numbers of Th17 cells [7], suggesting that in vivo other cytokines can compensate for its actions. One candidate is IL-21 that is produced by Th17 and follicular helper T cells (Tfh). IL-21 induces IL-17, itself and [15, 40, 41, 43] IL-21 also induces the expression of IL-23R. However, in disease models that depend on Th17 specification IL-6 seems to be more relevant than IL-21. While IL-6−/− mice are protected from EAE [44] the role of IL-21 in this model is less clear. In vivo, one study reported that the development of EAE was significantly reduced in IL-21−/− mice [40]; however, two other studies showed that the development of EAE was not impaired by the absence of IL-21 signals [45, 46]. Thus, it appears that both IL-6 and IL-21 can promote Th17 differentiation, but neither appears to be absolutely necessary in vivo.

TGF-β as requisite inductive factor or a modulator?

The data are very clear that the combination of TGF-β and IL-6 is a very effective means of inducing naive T cells to become IL-17 producers. Consistent with this idea is that deleting TGF-β has also been reported to inhibit Th17 differentiation in vivo [47][7, 8]. Accordingly, transgenic overexpression of TGF-β in T cells was associated with increased susceptibility to the development of EAE in mice injected with MOG peptide [7]. Recently, it has been reported that the downstream signals of TGF-β, Smad2 is important for TGF-β mediated Th17 cell generation [48] [49][50]. Smad2−/− mice showed less severe disease in a EAE model [50]. It has also been reported that CD4+ T cells lacking the molecular adaptor tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6) are more sensitive to TGF-β-induced Smad2/3 activation and exhibit a specific increase in Th17 differentiation [51].

However, imputing a role of TGF-β as an inductive factor in Th17 differentiation is complicated by the fact that mice lacking this cytokine or its receptor subunits, develop a fatal, systemic autoimmune disease [52–54]. Thus, the mechanism by which TGF-β induces Th17 development remains elusive and an essential role of TGF-β in Th17 differentiation has recently been challenged. Specifically, in mutant T cells lacking T-bet and STAT6, IL-6 alone was found to be sufficient to generate Th17 cells [55]. This suggests that TGF-β plays an indirect role in Th17 differentiation by suppressing the expression of T-bet and GATA3, and limiting differentiation to alternate fates.

The importance for TGF-β in the human Th17 differentiation has also complicated its potential role as an obligate inductive factor. Initial work showed that human Th17 differentiation could be induced in the absence of TGF-β; indeed, TGF-β was noted to be an inhibitor of IL-17 production [56–58]. Another study showed that TGF-β in conjunction with IL-21 can induce Th17 differentiation from human naïve T cells, while TGF-β in conjunction with IL-6 failed to do so [59].

Flesh out in more detail more recently, we have found TGF-β-independent Th17 differentiation occurs in normal mouse T cells. Furthermore, we showed that mutant mice with impaired TGFβR signaling have residual Th17 cells within the gut [60]. As in human T cells the combination of IL-6 with IL-1β and IL-23 is capable of inducing Th17 differentiation in mouse T cells [61]. This cell fate depends on IL-23R expression. IL-6 is sufficient to induce IL-23R expression and IL-23 further amplifies its receptor expression.

Amidst all this controversy, perhaps some lessons are emerging. First, is that there appears not to be a major, species-specific difference in the role of TGF-β in mice and humans [60]. Second, assuming that TGF-β is not an obligate specification factor for Th17 differentiation, one probable mode of action is the repression of T-bet expression [55]. Consistent with this view, Th17 cells generated in the absence TGF-β express T-bet along with IL-17. Low concentrations of TGF-β promote Th17 differentiation and this would ensure that T-bet levels remain low and thereby attenuate the tendency of Th17 cells to become Th1 cells [62]. However, high concentrations of TGF-β inhibit Th17 differentiation [63]. Likely, this is because high concentrations of TGF-β induce expression of Foxp3. In addition, TGF-β also suppresses IL-23R expression [15][60].

So where does this leave us? One possibility is that Th17 cells are heterogeneous. IL-17-producing cells generated in the presence of TGF-β, which lack T-bet and express IL-10, may be more important for homeostasis in the gut. By contrast, IL-17 producing T cells that express T-bet in sites of inflammation may be the bad actors that need to be targeted for therapies to be effective in autoimmunity.

A new role for an old cytokine

The prototypic inflammatory cytokine, IL-1 acquired a new role with the recognition that it is a major promoter of Th17 development in both mouse and man, synergizing with IL-6 and IL-23 [61][60]. Accordingly, IL1R−/− CD4+ T cells are severely impaired to differentiate towards Th17 cells in vivo and IL1R−/− mice show reduced incidence of EAE [64, 65]. Furthermore, γδ T cells activated by IL-1β and IL-23 produce IL-17, IL-21 and IL-22 [66]. The IL-1R has homology to Toll-like receptors (TLR), and IL-1 engagement of its receptor results in the recruitment of the adapter MyD88 and IL-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAK) [67]. A recent study has indicated that single Ig IL-1R-related molecule (SIGIRR), a negative regulator of IL-1R and TLR signaling, control Th17 cell differentiation and proliferation. The study also showed that IL-1-induced Th17 cell expansion is dependent on mTOR [68].

4. Regulation of IL-17 production by G-protein coupled receptors

S1P is an abundant lysophospholipid present in blood and lymph and signals via a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) denoted S1PR1. S1P regulates T cell trafficking and egress from lymphoid structures [69][70]. Addition of S1P to cultures of splenic CD4+ T cells has been reported to increase IL-17 and to reduce IFN-γ and IL-4 production [71]. Accordingly, transgenic overexpression of an S1P receptor resulted in enhanced IL-17 production [72]. Whether this is a critical means of regulating Th17 differentiation in vivo has not been established.

Prostaglandins are another class of lipids that signal via GPCR. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is highly induced during inflammation. Interestingly, culture of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells with PGE2 and IL-23 resulted in high levels of production of IL-17 and C-C chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20), with less IFN-γ and IL-22 [73]. PGE2 acts through both prostaglandin EP2- and EP4- mediated signaling and cyclic AMP pathways to upregulate IL-23R and IL-1R expression resulting in synergistic induction of Th17 cells with IL-23 and IL-1β [74]. In vivo administration of PGE2 induced IL-23-dependent IL-17 production and exacerbated collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) in mice [75].

5. Regulation of Th17 differentiation by transcription factors

5.1 Direct, critical role of STAT3 in Th17 specification

It has long been appreciated that a major means by which type I/II cytokines exert their effect is through signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) [76]. Notably, the major cytokines that induce IL-17, IL-23, IL-6, and IL-21, all activate STAT3. The critical role of STAT3 was established by the finding that deletion of STAT3 in T cells abrogated Th17 differentiation [77][78]. Conversely, retroviral overexpression of constitutively active STAT3 was sufficient to induce IL-17 production [79]. Importantly, conditional deficiency of Stat3 in CD4+ T cells impairs IL-17 production in vivo and limits IL-17-associated pathology [80][81][82].

The requirement for STAT3 in human IL-17 production was unraveled in patients with Hyper IgE syndrome (HIES). HIES is a primary immunodeficiency disorder due to dominant negative mutations of STAT3 [83][84]. We and others found that patients with HIES have severely impaired ability to produce Th17 cells [83] [84–87][88]. The impairment of STAT3 signaling and consequently attenuated Th17 generation may explain the patients’ inability to clear bacterial and fungal infections.

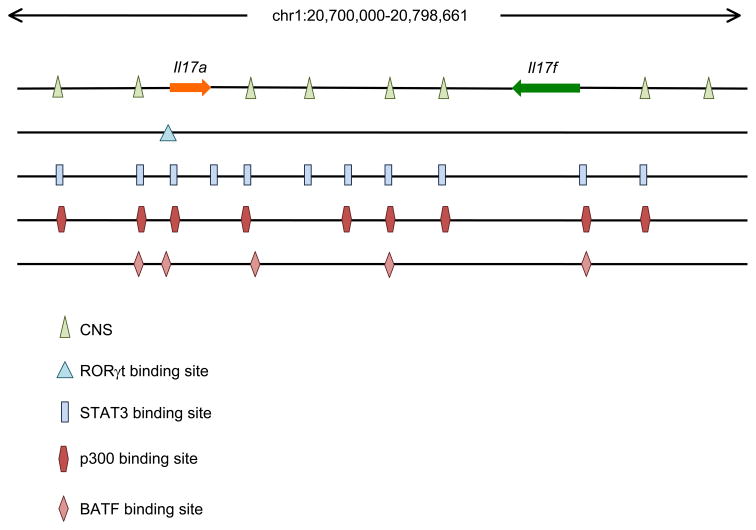

The demonstration of the importance of STAT3 in mouse and man raised the issue of exactly how STAT3 contributes to Th17 cell development. STAT3 initially found to directly bind to the Il-17 promoter by using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays [89]. However, new technology, namely ChIP and massive parallel sequencing (ChIP-seq) provides the opportunity to define the function of transcription factors on a genome-wide scale [90, 91]. The functional relevance of the binding can be ascertained by genome-wide transcriptional profiling and by assessing the transcription factor-dependent changes in epigenetic modifications. This has been accomplished for STAT3 in Th17 cells and it was found that STAT3 binds promoters and enhancers of many genes involved in Th17 development [82]. STAT3 binds throughout the Il17 and Il17f locus. Interestingly, its binding is not restricted just within the promoter regions, STAT3 also binds the intergenic region (Figure 1).

Fig 1. STAT3, p300, BATF and RORγt binding sites in the Il17/Il17f locus.

In addition to the previous identified STAT3 binding sites in the promoters of Il17 and Il17f in Th17 conditions [77], STAT3 have been found to bind strongly with multiple conserved non-coding sequences located in the intergenic region between Il17 and Il17f [82]. Binding sites of p300 has been found in this locus by our study [60]. Binding sites of BATF and RORγt has been reported by others [100] [97]. The significance of those individual binding sites is of interest for further investigations.

STAT3 also binds and regulates the Il21, Il21r and Il23r genes [60]. Importantly, STAT3 directly controls expression of many of the other transcription factors that participate in Th17 differentiation including Rorγt, IRF4, and Batf. Thus, this analysis revealed a greatly expanded role for STAT3 in Th17 differentiation. Interestingly, STAT3 has also been suggested to play a role in proliferation and survival of Th17 cells [82]. Furthermore, STAT3 is important both for the expression of IL-23R and the downstream signaling of this cytokine receptor complex [92].

5.2 Retinoid receptors and Th17 cells

Retinoid receptors comprise a family of nuclear receptors, only some members of which are regulated by metabolites of vitamin A. They are part of a larger family of steroid nuclear receptors and as such, have direct transcription factor properties. Retinoid receptors can be divided into three families: classical retinoic acid receptors (RARα-γ), retinoid X receptors (RXRα-γ) and the retinoic acid orphan receptors (RORα-γ). RORγt is a splice variant of the Rorc gene that results from initiation by a distinct promoter within the full length Rorc gene, resulting in products that differ in their amino terminus [93].

Whereas RORγ is ubiquitously expressed, a transcript denoted, RORγt, is exclusively expressed in lymphoid cells. RORγ is critical for T cell development and lymphoid organogenesis. This is evidenced by the fact that Rorc−/− mice exhibit reduced numbers of double positive and CD4+ single-positive thymocytes. Rorc−/− mice also lack lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches and lymphoid tissue inducer cells [94][95][96]. Rorc−/− mice also have reduced Th17 differentiation and have reduced disease severity in the EAE model [9]. Conversely, overexpression of RORγt promotes IL-17 expression; in this regard RORγt acts similarly to transcription factors such as T-bet and GATA3 in Th1 and Th2 differentiation respectively and therefore has been proposed to be a “master regulator” for Th17 differentiation. Multiple RORγt binding sites are present in the Il17 promoter, and by the use of ChIP, RORγt has been found to bind the Il17 gene [97] (Figure 1).

As indicated, STAT3 binds the Rorc gene and STAT3-deficient T cells have poor expression of RORγt [77–79][82]. However, overexpression of active STAT3 in Rorc−/− cells resulted in poor IL-17 induction [15], arguing that STAT3 is necessary but not sufficient for IL-17 expression. Rather, STAT3 and RORγt appear to act cooperatively on the Il17 locus to drive production of this cytokine.

Another related retinoic acid nuclear receptor, RORα, is also preferentially expressed in Th17 cells [98]. In contrast to RORγt though, deletion of Rora deletion had a minimal effect on IL-17 production. However, deficiency of both Rora and Rorc completely abolished IL-17 production and protected against EAE [98]. Co-expression of the two factors enhanced the number of IL-17-producing cells. Collectively, the findings suggest that there is some redundancy between the functions of RORγ and RORγt.

5.3 Batf and Th17 differentiation

Batf is a member of the AP-1 transcription factor family that contains a basic region and leucine zipper, lacks a transcriptional activation domain and so has been considered as an inhibitor of AP-1 transcriptional activity [99]. Recently though, it has been shown that Batf is essential for Th17 cell differentiation [100]. Batf−/− mice show a complete loss of Th17 differentiation and are resistant to the induction of EAE. However, Batf mRNA is not exclusively expressed in Th17 cells; it is expressed in Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells. Nonetheless, in vitro differentiation of Th1 and Th2 were apparently unaffected in the absence of Batf. Batf heterodimerizes with JunB in Th17 cells and binds the promoters of Il17, Il17f, Il21 and Il22 and the intergenic regions between Il17 and Il17f (Figure 1).

5.4 IRF4 and Th17 differentiation

IRF4, a member of the interferon regulatory factor (IRF) family of transcription factors, was originally implicated as a key inducer of GATA3 expression in Th2 lineage differentiation [101]. While, IRF4-deficient T cells were shown to impair IL-17 production in response to TGF-β and IL-6 [102]. Recently, It has been shown that phosphorylation of IRF4 regulates IL-17 and IL-21 production [103]. Moreover, IRF4-deficient mice are resistant to EAE [102]. It has been suggested that IRF4 might co-operate with STAT3 to induce RORγt expression, but IRF4 also interacts with NFATc1 and c2 [104] [105]. In this manner, it may affect other Th cell lineages. It is of note that this is a rare example of a factor required for both Th17 and Th2 development, which is in contrast with the previously accepted links with Th17 and Th1 development via IL-23 [5] and Th17 and Treg development via TGF-β [7].

5.5 Runx transcription factors

Runx transcription factors represent another critical family of proteins that regulate CD4+ T helper cell differentiation. There are three mammalian Runt domain transcription factors, Runx1, Runx2, and Runx3. Runx1 is crucial for normal hematopoiesis including thymic T cell development [106]. Additionally, both Runx1 and Runx3 are reported to act as repressors of CD4 and Zbtb7b (the latter being encodes Th-POK, a transcription factor that regulates CD4+ differentiation), but at different stages of thymocyte development to affect the CD4/CD8 lineage choice [107][108]. Runx3 also functions as a CD4 silencer in CD8+ T cells and is involved in a feed-forward regulatory circuit in which T-bet induces Runx3 and then ‘partners’ with Runx3 to direct activation of Ifng and silencing of Il4 [109][110]. In Treg cells, Runx1 binds the N-terminus of Foxp3. This interaction is required for Foxp3-mediated suppression of IL-2 production and suppression activity of Treg cells [111]. Recent work has indicated that Runx1 also plays a role in Th17 differentiation [112]. Both Runx1 and RORγt bind to the Il17 promoters and by interaction with distinct functional partners (RORγt versus Foxp3), Runx1 may contribute to both Treg and Th17 differentiation.

5.6 Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) belongs to a bHLH-PAS family of transcription factors and is highly conserved in evolution [113]. AHR senses a wide range of small synthetic compounds and natural ligands, including metabolites of tryptophan and arachidonic acids, dietary flavonols and kaempferols. Importantly, environmental toxins such 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) bind AHR. Upon ligand binding in the cytosol, AHR undergoes conformational change, translocates to the nucleus and dissociates with its chaperone Hsp90 and p23 [114].

Th17 cells preferentially express AHR and tryptophan-derived photoproduct 6-formylindolo [3,2-b] carbazole (FICZ), promote expression of IL-17, IL-17F and IL-22 [115] [116]. It has been shown that not only Th17 cells but also γδ T cells express AHR [117]. Mice lacking AHR have reduced severity in EAE; however, AHR is important for IL-22, but not IL-17 production [115]. Curiously, TCDD is profoundly immunosuppressive [118] and activation of AHR by TCDD expands CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells, which suppress EAE [119]. Recent work has indicated that activation of AHR also induces Foxp3+ Treg cells in human [120]. How different AHR agonists seem to have distinct effects is puzzling; however, AHR expression in Th17 cells provides an intriguing link as to how environmental toxins might contribute to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases.

5.7 Nuclear factor of activated T cells and NF-κB family

One consequence TCR ligation is elevation of intracellular Ca2+, which leads to the dephosphorylation and activation of members of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) transcription factor family. The proximal promoter of the human and mouse IL17 genes contain multiple NFAT binding sites [30, 121]. There are four isoforms of NFAT with incomplete functional redundancy [122]. Recently, it has been shown that CD4+ T cells expressing hyperactivable NFAT1 produce more IL-17 [123]. Moreover, proteins that interfere with the DNA binding of NFAT can regulate IL-17 expression. It has been demonstrated that NR2F6, a nuclear zinc-finger orphan receptor, acts as a transcriptional repressor of Th17 cells, similar to zinc-finger proteins that repress GATA3 and Th2 cells [124, 125]. However, we have to know more about the specific roles of the individual NFAT isoforms and binding partners in IL-17 production.

IL-1, a major promoter of Th17 development, activates NF-κB. A recent study has indicated that the NF-κB family member IκBζ regulates Th17 development by cooperating with ROR nuclear receptors [126]. A further member of the NF-κB family, c-Rel also plays a critical role in the differentiation of Th17 cells [127].

6. Negative Regulation of Th17 differentiation

6.1 Inhibition of Th17 differentiation by STAT proteins

In addition to positive roles in regulating Th17 differentiation, cytokines that bind type I/II cytokine receptors can negatively regulate Th17 differentiation. Consistent with work indicating that IFN-γ and IL-4 also antagonize Th2 and Th1 differentiation respectively, IFN-γ and IL-4 also inhibit IL-17 production [128][6]. IL-27 is an IL-12-related cytokine that consists of two subunits, p28 and EBI3 [129]. Like the IL-6R, the IL-27R complex contains gp130, but in addition it has a ligand-specific subunit termed WSX-1. Despite its similarities to IL-6, IL-27 has the opposite effect in regulating IL-17 expression; it is a critical negative regulator of Th17 differentiation [130][131]. Like IFN-γ, IL-27 activates STAT1 and the inhibitory effect of IL-27 on Th17 differentiation is abrogated in STAT1-deficient mice [131]. Further investigation is needed to understand the exact mechanisms by which STAT1 activation inhibits Th17 generation.

Activated by IL-12, STAT4 is well known as a critical positive regulator of Th1 differentiation and IFN-γ production. As both IL-12 and IFN-γ suppress IL-17 production, in an analogy to STAT1, the expectation might be that STAT4 would negatively regulate IL-17 expression. However, two studies have reported that IL-17 production is decreased in STAT4-deficient T cells, arguing for a positive role of STAT4 for IL-17 production [79, 132]. The decreased IL-17 production in STAT4-deficient T cells might be related to the impaired IL-23 signaling, as IL-23 has been suggested to activate STAT4 [133]. It will be of interest to further examine the role of STAT4 in Th17 differentiation.

IL-2 is a well-known T cell growth factor in vitro, but at the same time the deficiency of IL-2 results in severe multi-organ autoimmune disease in vivo [134]. This is in part due to its role in promoting the differentiation of Tregs by STAT5, but recent work has shown that IL-2 also suppresses Th17 differentiation in a STAT5-dependent manner [78] [135]. Like IL2−/− mice, STAT5-deficient mice suffer from inflammatory autoimmune disease that is associated with a loss of Treg cells and the simultaneous expansion of Th17 cells. STAT5a/b appear to be essential for Foxp3 expression and in constraining Th17 cells [78, 136]. However, the mechanisms underlying the blockade of Th17 differentiation by IL-2 via STAT5 are not entirely clear. One possibility is that this is mediated indirectly via induction of Foxp3, a factor known to bind and inhibit RORγt [137]. Alternatively, STAT5a/b might act as a direct repressor to inhibit Il17a expression [78].

6.2 Negative regulation of Th17 by nuclear receptors

In contrast to RORγt and RORγ, other retinoic acid nuclear receptors have been suggested to inhibit Th17 differentiation. Several groups have shown that retinoic acid inhibits Th1, Th2 and Th17 differentiation in vitro. Retinoic acid downregulates expression of RORγt and enhances the expression of Foxp3 [138–140]. Conversely, a RAR antagonist inhibited Foxp3 expression. Foxp3 binds to the Il17 promoter [137], thus Foxp3 and RORγt, directly interact and modify each other’s function [137].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors. Multiple natural and synthetic PPARγ ligands have been described to exert anti-inflammatory effects on various levels [141]. Upon ligand binding, PPARγ translocates into the nucleus and forms a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor and then binds to PPARγ response elements located in the promoter region of target genes. Recently the relevance of PPARγ in Th17 differentiation has been demonstrated with the use of the synthetic ligand, pioglitazone (PIO) [142]. Th17 differentiation and expression of Th17-assocated genes (Il23r, Il21, Il17 and Il17f) were dramatically inhibited by treatment of CD4+ T cells with PIO, but this had no effect on Th1 differentiation. PIO ameliorated EAE clinical scores and mice had fewer IL-17 producing cells in the CNS. Consistent with this, the mice lacking PPARγ in CD4+ T cells showed earlier onset and aggravated disease in the initial T cell-dependent phase of EAE. However, there was no difference in the later effector phase of disease.

6.3 Socs3

Suppressor of cytokine signaling (Socs3) is a cytokine-inducible negative regulator of STAT3; SOCS proteins are among the most prominent Stat-regulated genes [143] providing a negative feedback to STAT signaling. We first showed that T cell-specific deletion of Socs3 is associated with enhanced STAT3 phosphorylation and increased IL-17 production [89]. Deletion of Socs3 in the hematopoietic and endothelial cell compartment is associated with widespread autoimmune disease and increased susceptibility to both CIA and EAE [144].

6.4 MicroRNA and negative regulation of IL-17

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a large family of posttranscriptional regulators of gene expression that are approximately 21 nucleotides in length. Dicer is an RNaselll-like enzyme that is required for generating miRNAs [145]. Specific deletion of Dicer in T cells resulted in impaired T cell development and aberrant IFNγ production [146]. Ets-1 is a transcription factor that associates with T-bet and binds the Ifng promoter. Of note, Ets-1 deficiency results in enhanced Th17 differentiation, along with increased levels of mRNA for IL-22 and IL-23R [147]. Ets-1’s actions are likely to be indirect, as no binding of Ets-1 to the Il17 promoter was observed. Rather, Ets-1 appears to negatively regulate Th17 differentiation through effects on IL-2. Specifically, Ets-1 deficient T cells were found to secrete less IL-2 and have impaired responsiveness to this cytokine. Ets-1 has been found to be a target of microRNA mir-326 and mir-326 has been reported to be upregulated in patients with multiple sclerosis and in murine Th17 cells generated in vitro [148]. Overexpression of mir-326 enhances Th17 generation and disease severity in EAE whereas blocking mir-326 reduces Th17 generation and ameliorates disease severity of the EAE. This has been explained by regulating expression of Ets-1.

Recently, miRNA-, mRNA, and ChIP-seq were performed to characterize the microRNome during lymphopoiesis within the context of the transcriptome and epigenome [149]. The authors showed that H3K27me3 inhibited expression of induced miRNAs during lymphopoiesis [149]. These studies reveal some of the epigenetic, transcriptional, and posttranscriptional strategies that help orchestrate cellular abundance of miRNAs during lymphopoiesis.

7. Relationship of Th17 cells to other subsets: influence of epigenetic modification

Cellular differentiation is associated with heritable changes in chromatin in daughter cells that preserve gene expression. Epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, histone modifications and incorporation of histone variants can all contribute to regulate gene expression [150]. Cytokine genes in Th cell subsets are similarly regulated [151, 152].

The Il17 gene is linked to the Il17f gene on chromosome 1 (human chromosome 6) in a tail-to-tail configuration. Expression of these two cytokines is linked, although there are some circumstances in which there is selective expression of one or the other [153][154]. The promoter regions of both the Il17 and Il17f genes undergo histone H3 acetylation and K4 tri-methylation upon Th17 differentiation, implying increased accessibility of the locus [77]. Moreover, there are eight conserved noncoding sequences in this locus, four of which reside in the intergenic region, which also undergo preferential histone acetylation [77]. In addition to the promoters, STAT3 binds in this intergenic region and the accessible histone marks are STAT3-dependent [82]. Some of STAT3 binding sites are shared with p300 binding [60].

Although the standard model of Th1 and Th2 differentiation implies that these subsets behave like terminally differentiated cells, recent findings indicate more flexibility than envisioned and recent findings provide mechanisms for flexibility in expression of key transcription factors [155–157]. While the histone methylation at the proximal promoters of cytokines genes showed reciprocal permissive (H3K4me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) marks in cell subsets that express the signature cytokines, the histone methylation patterns of the key transcriptional factors for lineage specification exhibit bivalent modifications of those genes not expressed [156]. For example, the promoters of Tbx21 and Gata3 are modified by both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 in Th17 cells suggesting that these genes are poised for expression. This is consistent with the reported transition of Th2 to produce IFN-γ following viral infection [155]. In this context, it is perhaps not surprising that Th17 cells generated in vitro are intrinsically unstable [158][159][160]. In contrast, isolated memory Th17 cells appear to be more stable [161].

8. Conclusions

The past several years have certified an outburst of information pertaining to the new lineage of CD4+ T cells. In addition to Th1 and Th2 cells, we know that CD4+ T cell fate includes Th17, Treg (natural and inducible) and T follicular helper cells. The major cytokines required for Th17 differentiation have been identified, key transcription factors involved in their generation are continuingly to be identified, their function in animal models of autoimmune diseases and in models of infectious diseases have been established. On the other hand, there are still many more questions remained to be answered. What is the real relationship between all these subsets of cytokine-producing cells? To what extent are these lineages interconvertible or are they terminally differentiated? How do these processes relate to immunologic memory? Based on what we know about Th1 and Th2 cells, it would be expected that interactions between transcription factors and modifications and epigenetic modifications, and possibly intra- and interchromosal interactions, underlie selective regulation of cytokine genes. Understanding the molecular basis of these processes will be key to understanding the fates of differentiating T cells and the possibility of using specific lineages of cells as an attractive therapeutic target in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

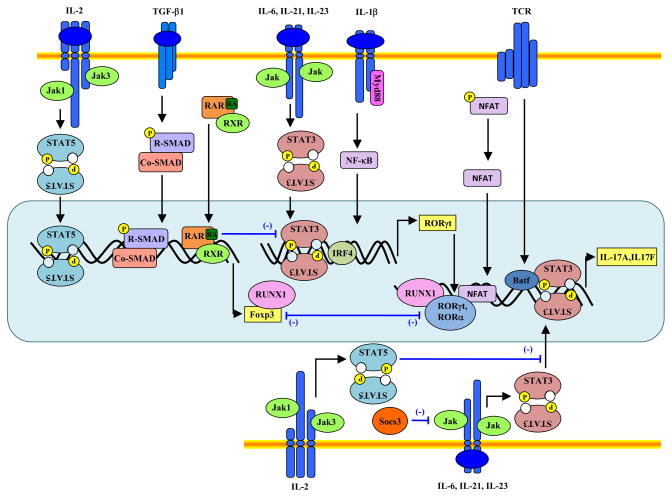

Fig 2. Signaling pathways and transcription factors that regulate Th17 differentiation.

TCR stimulation activates the transcription factor NFAT, which regulates IL-17 and IL-17F differentially. IL-6, IL-21 and IL-23 induce STAT3 activation, which in turn binds the Il17, I17f and Il21 genes. STAT3 binds to Rorc and Irf4 genes and IRF4 co-operates with STAT3 to induce RORγt expression. TGF-β1 signaling involves the activation of SMAD proteins, although the mechanism by which it promotes both iTreg and Th17 differentiation remains largely unknown. One possibility is that it does not provide inductive signals, but only attenuates expression of T-bet, GATA3 and other factors. IL-1 signals to potentiate IL-6-induced IRF4 expression thus promotes Th17 differentiation. Both RORγt and RORα bind the Il17 gene. In contrast, IL-2, IL-4, IL-27 and IFN-γ inhibit Th17 differentiation through STAT5, STAT6 and STAT1 activation respectively, although the underlying mechanism(s) are not completely understood. Reciprocally, STAT5 upregulates Foxp3 expression. Runx1 associates with both RORγt and Foxp3 and possibly regulates differentiation towards either the iTreg or Th17 lineage. Cytokines also upregulate Socs3, which attenuates STAT3 activation.

Table 1.

Mediators and transcription factors that positively or negatively regulate Th17 differentiation

| Factors positively regulating Th17 differentiation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter | Ref. | ||

| Itk | Mouse | 2 | [30] |

| Raftlin | Mouse | 2 | [31] |

| IL-1 | Mouse and Human | 3 | [60][61] [64, 65] |

| IL-6 | Mouse and Human | 3 | [5][7][8][9][10][61] |

| IL-21 | Mouse and Human | 3 | [15][40][41][59] |

| IL-23 | Mouse and Human | 3 | [15][38][56] |

| S1P | Mouse | 4 | [71] [72] |

| PGE2 | Mouse and Human | 4 | [73] [74] [75] |

| STAT3 | Mouse and Human | 5.1 | [77] [78] [79] [80] [81] [82] [83] [84–87] [88] |

| RORγ | Mouse | 5.2 | [9] |

| Batf | Mouse | 5.3 | [100] |

| IRF4 | Mouse | 5.4 | [102] [103] |

| Runx1 | Mouse | 5.5 | [112] |

| AHR | Mouse and Human | 5.6 | [115] [116] |

| IκBζ | Mouse | 5.7 | [126] |

| c-Rel | Mouse | 5.7 | [127] |

| Factors negatively regulating Th17 differentiation | |||

| IL-2 | Mouse | 6.1 | [78] [135] |

| IL-4 | Mouse | 6.1 | [6] |

| IL-27 | Mouse | 6.1 | [130][131] |

| IFNγ | Mouse | 6.1 | [6] |

| STAT5 | Mouse | 6.1 | [78, 136] |

| Retinoic acid | Mouse | 6.2 | [138–140] |

| Socs3 | Mouse | 6.3 | [89] |

| Mir-326 | Mouse and Human | 6.4 | [148] |

Acknowledgments

Work of the authors was supported by NIH/NIAMS Intramural Research Program (IRP).

Biographies

Kiyoshi Hirahara is a visiting fellow in the Molecular Immunology and Inflammation Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases, NIH, USA. He received his MD degree from Niigata University, Japan. He trained in immunology at Chiba University (Professor Toshinori Nakayama) and received his PhD degree from Niigata University Graduate School (Professor Fumitake Gejyo). As a pulmonologist he is mainly interested in lung cancer and has worked under the mentorship of Associate Professor Hirohisa Yoshizawa (Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital). His current research focuses on the relation between cytokine receptors and STAT proteins in CD4+ T-cells.

Kamran Ghoreschi is a visiting fellow in the Molecular Immunology and Inflammation Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (Dr. John J. O’Shea), NIH, USA. He graduated from the medical school of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Munich and completed his training as a dermatologist and allergist from the Dermatology departments of the universities of Munich (Professor Gerd Plewig) and Tübingen (Professor Martin Röcken), Germany. His doctorate thesis was on intraepithelial T-cells. His clinical research focuses on psoriasis, inflammatory autoimmune diseases and allergies. His experimental research interests include cytokine signaling, T-cell differentiation and immunomodulation with small molecules.

Xiang-Ping Yang is a visiting fellow in the Molecular Immunology and Inflammation Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin, NIH, USA. He obtained his PhD degree in biochemistry from the Aachen Technical University (RWTH, Aachen, Germany) on the negative regulation of Jak-Stat pathway (Professor Peter C. Heinrich). Before joining Dr. O’Shea’s laboratory, he had a postdoctoral training on T-cell signaling at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, UK (Professor Oreste Acuto). Currently his research focuses on the regulation of T-cell differentiation and related autoimmune diseases by cytokines, transcription factors and epigenetic modifications.

Yuka Kanno received her M.D., Ph.D. from Tohoku University School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan, and arrived at The National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, U.S.A. as a postdoctoral fellow. She now conducts her research as a staff scientist in Dr. John O’Shea’s laboratory in NIH. Her primary research interest has been the regulation of gene expression by transcription factors. Using JAK-STAT signaling pathway a model system, her recent study focuses on profiling chromatin conformation following STAT activation in immune cells. She hopes to understand cell-type specific genomic organization that regulates gene expression during normal and pathological immune responses.

Arian Laurence is a visiting fellow in the Molecular Immunology and Inflammation branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin, NIH, Bethesda MD. He graduated from Guys Hospital Medical School, London University and completed his training in Hematology at University college Hospital London. His doctorate thesis was at Cancer Research UK, London Research Institute (Professor Doreen Cantrell, Professor David Linch) in the field of T cell signaling and his current research continues in this field.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mosmann TR, et al. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136(7):2348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnello D, et al. Cytokines and transcription factors that regulate T helper cell differentiation: new players and new insights. J Clin Immunol. 2003;23(3):147–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1023381027062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mowen KA, Glimcher LH. Signaling pathways in Th2 development. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:203–22. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrington LE, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(11):1123–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park H, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(11):1133–41. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bettelli E, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441(7090):235–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangan PR, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441(7090):231–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanov, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126(6):1121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang SC, et al. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J Exp Med. 2006;203(10):2271–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye P, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194(4):519–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amadi-Obi A, et al. TH17 cells contribute to uveitis and scleritis and are expanded by IL-2 and inhibited by IL-27/STAT1. Nat Med. 2007;13(6):711–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annunziato F, et al. Type 17 T helper cells-origins, features and possible roles in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5(6):325–31. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinman L. Mixed results with modulation of TH-17 cells in human autoimmune diseases. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(1):41–4. doi: 10.1038/ni.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou L, et al. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):967–74. doi: 10.1038/ni1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saijo S, et al. Dectin-2 recognition of alpha-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity. 2010;32(5):681–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyttaris VC, et al. Cutting edge: IL-23 receptor deficiency prevents the development of lupus nephritis in C57BL/6-lpr/lpr mice. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):4605–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veldhoen M, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta ‘reprograms’ the differentiation of T helper 2 cells and promotes an interleukin 9-producing subset. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(12):1341–6. doi: 10.1038/ni.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurieva RI, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29(1):138–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duhen T, et al. Production of interleukin 22 but not interleukin 17 by a subset of human skin-homing memory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(8):857–63. doi: 10.1038/ni.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGeachy MJ, et al. TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(12):1390–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(6):389–400. doi: 10.1038/nri821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakaguchi S, et al. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133(5):775–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Josefowicz SZ, Rudensky A. Control of regulatory T cell lineage commitment and maintenance. Immunity. 2009;30(5):616–25. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michel ML, et al. Identification of an IL-17-producing NK1.1(neg) iNKT cell population involved in airway neutrophilia. J Exp Med. 2007;204(5):995–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stark MA, et al. Phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils regulates granulopoiesis via IL-23 and IL-17. Immunity. 2005;22(3):285–94. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu J, Paul WE. CD4 T cells: fates, functions, and faults. Blood. 2008;112(5):1557–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iezzi G, et al. CD40-CD40L cross-talk integrates strong antigenic signals and microbial stimuli to induce development of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(3):876–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810769106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berg LJ, et al. Tec family kinases in T lymphocyte development and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:549–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomez-Rodriguez J, et al. Differential expression of interleukin-17A and -17F is coupled to T cell receptor signaling via inducible T cell kinase. Immunity. 2009;31(4):587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saeki K, et al. A major lipid raft protein raftlin modulates T cell receptor signaling and enhances th17-mediated autoimmune responses. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):5929–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nurieva RI, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase GRAIL regulates T cell tolerance and regulatory T cell function by mediating T cell receptor-CD3 degradation. Immunity. 2010;32(5):670–80. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purvis HA, et al. Low strength T-cell activation promotes Th17 responses. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-272153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee K, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin protein complex 2 regulates differentiation of Th1 and Th2 cell subsets via distinct signaling pathways. Immunity. 2010;32(6):743–53. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galicia G, et al. ICOS deficiency results in exacerbated IL-17 mediated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29(4):426–33. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauquet AT, et al. The costimulatory molecule ICOS regulates the expression of c-Maf and IL-21 in the development of follicular T helper cells and TH-17 cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(2):167–75. doi: 10.1038/ni.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oppmann B, et al. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13(5):715–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aggarwal S, et al. Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(3):1910–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cua DJ, et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421(6924):744–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nurieva R, et al. Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature. 2007;448(7152):480–3. doi: 10.1038/nature05969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korn T, et al. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448(7152):484–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veldhoen M, et al. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24(2):179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei L, et al. IL-21 is produced by Th17 cells and drives IL-17 production in a STAT3-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(48):34605–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705100200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samoilova EB, et al. IL-6-deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: roles of IL-6 in the activation and differentiation of autoreactive T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161(12):6480–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonderegger I, et al. IL-21 and IL-21R are not required for development of Th17 cells and autoimmunity in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(7):1833–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coquet JM, et al. Cutting edge: IL-21 is not essential for Th17 differentiation or experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;180(11):7097–101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veldhoen M, et al. Signals mediated by transforming growth factor-beta initiate autoimmune encephalomyelitis, but chronic inflammation is needed to sustain disease. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(11):1151–6. doi: 10.1038/ni1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malhotra N, Kang J. SMAD2 is essential for TGF beta mediated Th17 cell generation. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.156745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinez GJ, et al. SMAD2 positively regulates the generation of Th17 cells. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.155820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takimoto T, et al. Smad2 and Smad3 are redundantly essential for the TGF-beta-mediated regulation of regulatory T plasticity and Th1 development. J Immunol. 2010;185(2):842–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cejas PJ, et al. TRAF6 inhibits Th17 differentiation and TGF-beta-mediated suppression of IL-2. Blood. 2010;115(23):4750–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Letterio JJ, Roberts AB. Regulation of immune responses by TGF-beta. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:137–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shull MM, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359(6397):693–9. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang X, et al. Targeted disruption of SMAD3 results in impaired mucosal immunity and diminished T cell responsiveness to TGF-beta. EMBO J. 1999;18(5):1280–91. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Das J, et al. Transforming growth factor beta is dispensable for the molecular orchestration of Th17 cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 2009;206(11):2407–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Z, et al. Distinct regulation of interleukin-17 in human T helper lymphocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):2936–46. doi: 10.1002/art.22866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, et al. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(6):639–46. doi: 10.1038/ni1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Annunziato F, et al. Human Th17 cells: are they different from murine Th17 cells? Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(3):637–40. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang L, et al. IL-21 and TGF-beta are required for differentiation of human T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2008;454(7202):350–2. doi: 10.1038/nature07021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghoreschi K, et al. Generation of pathogenic Th17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signaling. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, et al. Interleukins 1beta and 6 but not transforming growth factor-beta are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):942–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee YK, et al. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity. 2009;30(1):92–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manel N, Unutmaz D, Littman DR. The differentiation of human T(H)-17 cells requires transforming growth factor-beta and induction of the nuclear receptor RORgammat. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(6):641–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sutton C, et al. A crucial role for interleukin (IL)-1 in the induction of IL-17-producing T cells that mediate autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2006;203(7):1685–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben-Sasson SZ, et al. IL-1 acts directly on CD4 T cells to enhance their antigen-driven expansion and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(17):7119–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902745106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sutton CE, et al. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2009;31(2):331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: 10 years of progress. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:10–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gulen MF, et al. The receptor SIGIRR suppresses Th17 cell proliferation via inhibition of the interleukin-1 receptor pathway and mTOR kinase activation. Immunity. 2010;32(1):54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matloubian M, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427(6972):355–60. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosen H, Goetzl EJ. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and its receptors: an autocrine and paracrine network. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(7):560–70. doi: 10.1038/nri1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liao JJ, Huang MC, Goetzl EJ. Cutting edge: Alternative signaling of Th17 cell development by sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Immunol. 2007;178(9):5425–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang MC, et al. Th17 augmentation in OTII TCR plus T cell-selective type 1 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor double transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2007;178(11):6806–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chizzolini C, et al. Prostaglandin E2 synergistically with interleukin-23 favors human Th17 expansion. Blood. 2008;112(9):3696–703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boniface K, et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates Th17 cell differentiation and function through cyclic AMP and EP2/EP4 receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 2009;206(3):535–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sheibanie AF, et al. Prostaglandin E2 exacerbates collagen-induced arthritis in mice through the inflammatory interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2608–19. doi: 10.1002/art.22794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228(1):273–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang XO, et al. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):9358–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Laurence A, et al. Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity. 2007;26(3):371–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mathur AN, et al. Stat3 and Stat4 direct development of IL-17-secreting Th cells. J Immunol. 2007;178(8):4901–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu X, et al. Loss of STAT3 in CD4+ T cells prevents development of experimental autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):6070–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harris TJ, et al. Cutting edge: An in vivo requirement for STAT3 signaling in TH17 development and TH17-dependent autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2007;179(7):4313–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Durant L, et al. Diverse targets of the transcription factor STAT3 contribute to T cell pathogenicity and homeostasis. Immunity. 2010;32(5):605–15. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holland SM, et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16):1608–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Minegishi Y, et al. Dominant-negative mutations in the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 cause hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2007;448(7157):1058–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Milner JD, et al. Impaired T(H)17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2008;452(7188):773–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ma CS, et al. Deficiency of Th17 cells in hyper IgE syndrome due to mutations in STAT3. J Exp Med. 2008;205(7):1551–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Beaucoudrey L, et al. Mutations in STAT3 and IL12RB1 impair the development of human IL-17-producing T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205(7):1543–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Renner ED, et al. Novel signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) mutations, reduced T(H)17 cell numbers, and variably defective STAT3 phosphorylation in hyper-IgE syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(1):181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen Z, et al. Selective regulatory function of Socs3 in the formation of IL-17-secreting T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(21):8137–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600666103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mardis ER. ChIP-seq: welcome to the new frontier. Nat Methods. 2007;4(8):613–4. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0807-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(10):669–80. doi: 10.1038/nrg2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McGeachy MJ, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(3):314–24. doi: 10.1038/ni.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jetten AM. Retinoid-related orphan receptors (RORs): critical roles in development, immunity, circadian rhythm, and cellular metabolism. Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e003. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sun Z, et al. Requirement for RORgamma in thymocyte survival and lymphoid organ development. Science. 2000;288(5475):2369–73. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kurebayashi S, et al. Retinoid-related orphan receptor gamma (RORgamma) is essential for lymphoid organogenesis and controls apoptosis during thymopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(18):10132–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eberl G, Littman DR. The role of the nuclear hormone receptor RORgammat in the development of lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. Immunol Rev. 2003;195:81–90. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ichiyama K, et al. Foxp3 inhibits RORgammat-mediated IL-17A mRNA transcription through direct interaction with RORgammat. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(25):17003–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang XO, et al. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity. 2008;28(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wagner EF, Eferl R. Fos/AP-1 proteins in bone and the immune system. Immunol Rev. 2005;208:126–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schraml BU, et al. The AP-1 transcription factor Batf controls T(H)17 differentiation. Nature. 2009;460(7253):405–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lohoff M, et al. Dysregulated T helper cell differentiation in the absence of interferon regulatory factor 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(18):11808–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182425099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brustle A, et al. The development of inflammatory T(H)-17 cells requires interferon-regulatory factor 4. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):958–66. doi: 10.1038/ni1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Biswas PS, et al. Phosphorylation of IRF4 by ROCK2 regulates IL-17 and IL-21 production and the development of autoimmunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(9):3280–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI42856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hu CM, et al. Modulation of T cell cytokine production by interferon regulatory factor-4. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(51):49238–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rengarajan J, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) interacts with NFATc2 to modulate interleukin 4 gene expression. J Exp Med. 2002;195(8):1003–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Collins A, Littman DR, Taniuchi I. RUNX proteins in transcription factor networks that regulate T-cell lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(2):106–15. doi: 10.1038/nri2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Taniuchi I, et al. Differential requirements for Runx proteins in CD4 repression and epigenetic silencing during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 2002;111(5):621–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Setoguchi R, et al. Repression of the transcription factor Th-POK by Runx complexes in cytotoxic T cell development. Science. 2008;319(5864):822–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1151844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Djuretic IM, et al. Transcription factors T-bet and Runx3 cooperate to activate Ifng and silence Il4 in T helper type 1 cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(2):145–53. doi: 10.1038/ni1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Naoe Y, et al. Repression of interleukin-4 in T helper type 1 cells by Runx/Cbf beta binding to the Il4 silencer. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1749–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hu H, et al. Transcriptional partners in regulatory T cells: Foxp3, Runx and NFAT. Trends Immunol. 2007;28(8):329–32. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang F, Meng G, Strober W. Interactions among the transcription factors Runx1, RORgammat and Foxp3 regulate the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(11):1297–306. doi: 10.1038/ni.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Esser C, Rannug A, Stockinger B. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor in immunity. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(9):447–54. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Beischlag TV, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2008;18(3):207–50. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v18.i3.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Veldhoen M, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature. 2008;453(7191):106–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Veldhoen M, et al. Natural agonists for aryl hydrocarbon receptor in culture medium are essential for optimal differentiation of Th17 T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206(1):43–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Martin B, et al. Interleukin-17-producing gammadelta T cells selectively expand in response to pathogen products and environmental signals. Immunity. 2009;31(2):321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kerkvliet NI. Recent advances in understanding the mechanisms of TCDD immunotoxicity. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2(2–3):277–91. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Quintana FJ, et al. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 2008;453(7191):65–71. doi: 10.1038/nature06880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gandhi R, et al. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor induces human type 1 regulatory T cell-like and Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(9):846–53. doi: 10.1038/ni.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Liu XK, Lin X, Gaffen SL. Crucial role for nuclear factor of activated T cells in T cell receptor-mediated regulation of human interleukin-17. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(50):52762–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Macian F. NFAT proteins: key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(6):472–84. doi: 10.1038/nri1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ghosh S, et al. Hyperactivation of nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFAT1) in T cells attenuates severity of murine autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(34):15169–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009193107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hermann-Kleiter N, et al. The nuclear orphan receptor NR2F6 suppresses lymphocyte activation and T helper 17-dependent autoimmunity. Immunity. 2008;29(2):205–16. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hirahara K, et al. Repressor of GATA regulates TH2-driven allergic airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(3):512–20. e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Okamoto K, et al. IkappaBzeta regulates T(H)17 development by cooperating with ROR nuclear receptors. Nature. 2010;464(7293):1381–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chen G, et al. Regulation of the IL-21 gene by the NF-kappaB transcription factor c-Rel. J Immunol. 2010;185(4):2350–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ghoreschi K, et al. Interleukin-4 therapy of psoriasis induces Th2 responses and improves human autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2003;9(1):40–6. doi: 10.1038/nm804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pflanz S, et al. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2002;16(6):779–90. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Batten M, et al. Interleukin 27 limits autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing the development of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(9):929–36. doi: 10.1038/ni1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stumhofer JS, et al. Interleukin 27 negatively regulates the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells during chronic inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(9):937–45. doi: 10.1038/ni1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hildner KM, et al. Targeting of the transcription factor STAT4 by antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides suppresses collagen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2007;178(6):3427–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Watford WT, et al. Signaling by IL-12 and IL-23 and the immunoregulatory roles of STAT4. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:139–56. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Malek TR. The biology of interleukin-2. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:453–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lohr J, et al. Role of IL-17 and regulatory T lymphocytes in a systemic autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2006;203(13):2785–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yao Z, et al. Nonredundant roles for Stat5a/b in directly regulating Foxp3. Blood. 2007;109(10):4368–75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-055756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zhou L, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453(7192):236–40. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mucida D, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317(5835):256–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Coombes JL, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1757–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Elias KM, et al. Retinoic acid inhibits Th17 polarization and enhances FoxP3 expression through a Stat-3/Stat-5 independent signaling pathway. Blood. 2008;111(3):1013–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Szanto A, Nagy L. The many faces of PPARgamma: anti-inflammatory by any means? Immunobiology. 2008;213(9–10):789–803. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Klotz L, et al. The nuclear receptor PPAR{gamma} selectively inhibits Th17 differentiation in a T cell-intrinsic fashion and suppresses CNS autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2009 doi: 10.1084/jem.20082771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yoshimura A, Naka T, Kubo M. SOCS proteins, cytokine signalling and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(6):454–65. doi: 10.1038/nri2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wong PK, et al. SOCS-3 negatively regulates innate and adaptive immune mechanisms in acute IL-1-dependent inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1571–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI25660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Muljo SA, et al. Aberrant T cell differentiation in the absence of Dicer. J Exp Med. 2005;202(2):261–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Moisan J, et al. Ets-1 is a negative regulator of Th17 differentiation. J Exp Med. 2007;204(12):2825–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Du C, et al. MicroRNA miR-326 regulates TH-17 differentiation and is associated with the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(12):1252–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kuchen S, et al. Regulation of microRNA expression and abundance during lymphopoiesis. Immunity. 2010;32(6):828–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Lee GR, et al. T helper cell differentiation: regulation by cis elements and epigenetics. Immunity. 2006;24(4):369–79. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Wilson CB, Rowell E, Sekimata M. Epigenetic control of T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(2):91–105. doi: 10.1038/nri2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Chang SH, Dong C. A novel heterodimeric cytokine consisting of IL-17 and IL-17F regulates inflammatory responses. Cell Res. 2007;17(5):435–40. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Liang SC, et al. An IL-17F/A heterodimer protein is produced by mouse Th17 cells and induces airway neutrophil recruitment. J Immunol. 2007;179(11):7791–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Hegazy AN, et al. Interferons direct Th2 cell reprogramming to generate a stable GATA-3(+)T-bet(+) cell subset with combined Th2 and Th1 cell functions. Immunity. 32(1):116–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Wei G, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30(1):155–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 327(5969):1098–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Shi G, et al. Phenotype switching by inflammation-inducing polarized Th17 cells, but not by Th1 cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(10):7205–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Bending D, et al. Highly purified Th17 cells from BDC2.5NOD mice convert into Th1-like cells in NOD/SCID recipient mice. J Clin Invest. 2009 doi: 10.1172/JCI37865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Mukasa R, et al. Epigenetic instability of cytokine and transcription factor gene loci underlies plasticity of the T helper 17 cell lineage. Immunity. 2010;32(5):616–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Lexberg MH, et al. Th memory for interleukin-17 expression is stable in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(10):2654–64. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]