Abstract

Our objective was to establish the pattern of spread in lower limb-onset ALS (contra- versus ipsi-lateral) and its contribution to prognosis within a multivariate model. Pattern of spread was established in 109 sporadic ALS patients with lower limb-onset, prospectively recorded in Oxford and Sheffield tertiary clinics from 2001 to 2008. Survival analysis was by univariate Kaplan-Meier log-rank and multivariate Cox proportional hazards. Variables studied were time to next limb progression, site of next progression, age at symptom onset, gender, diagnostic latency and use of riluzole. Initial progression was either to the contralateral leg (76%) or ipsilateral arm (24%). Factors independently affecting survival were time to next limb progression, age at symptom onset, and diagnostic latency. Time to progression as a prognostic factor was independent of initial direction of spread. In a regression analysis of the deceased, overall survival from symptom onset approximated to two years plus the time interval for initial spread. In conclusion, rate of progression in lower limb-onset ALS is not influenced by whether initial spread is to the contralateral limb or ipsilateral arm. The time interval to this initial spread is a powerful factor in predicting overall survival, and could be used to facilitate decision-making and effective care planning.

Keywords: Epidemiology, prognostic, survival

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is characterized by progressive degeneration of cortical, brainstem, and spinal motor neurons. The region of onset is typically within the upper limb, lower limb or bulbar musculature, and the subsequent rate of disease progression is highly variable. Median survival in population based studies of ALS is consistently two to four years (1), but the distribution is skewed and at least 5% of patients in clinic based observations survive more than a decade (2), particularly those with limb-onset.

‘Flail arm’ ALS is a regional phenotypic variant with a predominantly symmetrical pattern of disease that remains confined for an extended period to the arms, and is associated with a slower rate of disease progression (3). A similar regional syndrome in the lower limbs is recognized, also characterized by contralateral rather than rostral spread of weakness, and variously described as ‘creeping paralysis’ – the pseudopolyneuritic variant (4), or ‘flail leg’ ALS (5). However, this more slowly progressive phenotype may be not be as easily distinguished from ‘typical’ ALS at diagnosis, or even be defined post hoc in ‘long survivors’. In the present era, where an effective therapy for ALS is lacking, an accurate prospective prognosis as soon after diagnosis as possible is vital to decision-making and care planning. In this clinic based study, we used the broad phenotype of lower limb-onset ALS to test the contribution of direction of spread (contra- versus ipsi-lateral) to overall prognosis.

Methods

Sporadic ALS patients seen at two tertiary referral ALS centres (Oxford and Sheffield) from 2003 to 2008 were prospectively recorded in a database as part of clinical care. Diagnosis was made by consultant neurologists with extensive experience of ALS (KT, MT and PJS), after exclusion of other conditions. Only patients with clearly identified, lateralized onset of weakness or wasting in a lower limb were analysed. Individuals with primary lateral sclerosis (PLS – by definition a markedly slowly progressive, and often lower limb-onset, syndrome) were excluded.

Progression of disease was defined by extension of weakness or wasting beyond the lower limb of onset, established through a combination of patient reporting and examination findings. The time to progression was calculated in months from the date of symptom onset. Follow-up for survival (defined by date of symptom onset) was carried out at intervals and date of death recorded. Where there was no follow-up after initial diagnosis, or incomplete written records for follow-up visits with respect to spread of symptoms or signs, the subject was excluded from analysis. Survival was calculated where status was definitely known at the time of censoring (1 July 2008). Age at symptom onset was also recorded, and any use of riluzole. The ‘diagnostic latency’ (an established prognostic marker) was calculated by subtracting the date of diagnosis at the respective tertiary clinic from the date of reported symptom onset.

Independence of variables was tested using the χ2 test. Survival analysis was by univariate Kaplan-Meier log-rank and multivariate Cox proportional hazards. Variables used in the model were time to progression, site of next progression, age at symptom onset, gender, diagnostic latency and use of riluzole.

A separate regression function was calculated for survival versus time to progression for those patients who had died.

Calculations were performed using SPSS (Version 14, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

There were 498 sporadic ALS patients entered into the tertiary clinic databases between January 2001 and 1 July 2008. Of these, 370 (74%) were classified as limb-onset ALS, of which 144 (29%) were identified with definite leg-onset. One case of premature death by suicide was excluded from the subsequent analysis. Survival data were complete for 98% of cases.

The proportion of patients alive at censoring was 31%. Median survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis was 41 months (95% CI 33–49), mean 73 months (95% CI 53–92), range 5–285 months. Overall, 51% of leg-onset ALS cases were male, and the mean age at symptom onset was 60 years (males 59, females 61, range 33–84 years). The median latency from symptom onset to diagnosis was 15 months (mean, 22 months; SD 23; range 2–216 months). The proportion of patients taking riluzole was 62%.

It was possible to establish the site of next involvement with certainty in 78% of cases (n = 109), where it was the contralateral lower limb in 76%, and ipsilateral upper limb in 24%. There were no cases of consecutive involvement of the contralateral upper limb or bulbar region. In the 90% of these individuals where it could be clearly ascertained, the median time to progression beyond the limb of onset was 12 months (mean, 23 months; SD 25; range 1–210 months). The mean time interval for spread to the contralateral leg was 21 months (SD 29), and for ipsilateral spread 16 months (SD 19; p = 0.43, independent t-test, equal variances assumed).

Significant prognostic variables in univariate Kaplan-Meier (K-M) analysis were: diagnostic latency (stratified for this analysis in yearly intervals from 0–60 months, then all cases above 60 months; log-rank χ2, 42; p < 0.0005), and time to progression (stratified for this analysis in the same way; log-rank χ2, 43; p < 0.0005). Gender was not found to be a significant prognostic factor (p = 0.17), nor age of onset in univariate categorical K-M analysis (age <50 years, median survival 59 months; age >=50 years, median survival 40 months; p = 0.13). There was no significant difference in survival between those whose disease spread next to the contralateral lower limb versus ipsilateral upper limb (contralateral leg median survival, 49 months; ipsilateral arm median survival, 38 months; p = 0.32). The use of riluzole was associated with an adverse survival (median survival in those taking riluzole, 36 months versus 57 months not taking riluzole; p < 0.01).

To take into consideration confounding variables, we used the Cox proportional hazards model to analyse survival data including all six variables (n = 83). Factors independently affecting survival within the model were diagnostic latency, time to progression beyond the leg of onset, and age at symptom onset (Model χ2 22, df 6, p < 0.001) (Table I).

Table 1.

Cox proportional hazards model. Diagnostic latency, age at symptom onset and time of progression to another limb remain independently significant prognostic factors. Contra- versus ipsi-lateral spread, gender and use of riluzole are not independently significant factors.

| Variable | Relative risk | p |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic latency (months)* | .964 | .028* |

| Time to progression (months)* | .967 | .016* |

| Gender | .939 | .822 |

| Age at onset (years)* | 1.046 | .002* |

| Contralateral leg versus ipsilateral arm |

1.690 | .111 |

| Use of riluzole | .928 | .796 |

statistically significant

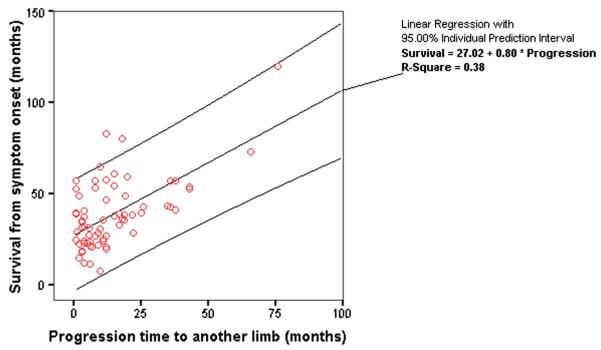

In a scatter plot of survival against time to progression in those patients who had died (median survival, 33 months; mean, 38 months; SD 21; range 5–120 months; n = 96), a regression function was fitted, in which overall survival in months from symptom onset approximated to two years plus the time to progression in months (r2 = 0.38) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of overall survival against time from onset to progression to another limb (in months) in patients with lower limb-onset ALS who had died at the time of censoring. Regression line and individual 95% confidence intervals are shown. The overall survival is approximately two years plus the time to progression.

Discussion

This clinic-based study in lower limb-onset ALS patients demonstrated that the time to progression of weakness or wasting beyond the limb of onset is a significant prognostic factor, and independent of whether spread was to the contralateral leg or ipsilateral arm. In the subgroup of patients who died, overall survival from symptom onset approximated to two years plus the time to symptomatic weakness or wasting appearing beyond the limb of onset. This has the potential to permit meaningful prognostic counselling of ALS patients at the point at which weakness or wasting spreads beyond the lower limb of onset.

Understanding of ALS pathogenesis is lacking at present, but the pattern of motor neuron vulnerability is not fully explained by any simple length-dependent mechanism, not least from the observation that lower limb-onset constitutes approximately 30% of cases only, with upper limb and bulbar-onset cases equally represented. Longitudinal clinico-pathological studies of ALS suggest that the site of onset is the most severely affected, with spread outward to contiguous body regions, and that UMN and LMN loss occur independently of each other (6–8). We, like others (9), observed in this study that sequential spread in lower limb-onset patients is only either to the ipsilateral arm or contralateral leg, supporting the concept of focal onset and radiating involvement of LMNs.

We defined progression by subjective measures. It has been estimated that 30% of anterior horn cells must be lost before weakness is apparent (10), so this is clearly a late feature of the underlying pathological process, potentially compounded by recall bias and assessor variability. While electromyography (EMG) is routinely used to detect subclinical LMN involvement in the diagnostic process, very few patients in our practice undergo repeated EMG as part of their routine management, so use of this investigation as a potentially more objective measure of LMN involvement was not possible. Furthermore, EMG would not capture any contribution of UMN dysfunction to weakness.

PLS patients were excluded from our study. Typically, PLS patients have lower limb-onset, and by definition an UMN-only phenotype, without evidence of wasting at diagnosis, and consistently markedly slow progression (11). Our aim in this study was to understand the pattern of spread in a group of more typical ALS patients, in whom survival is much more variable and not always easy to predict. One limitation is that, due to lack of recorded information, we were unable to take into account the relative degree of UMN versus LMN involvement in our subjects and potentially include this in the model. However, the El Escorial classification at diagnosis (which is based on the presence of UMN signs) has inconsistent value as a prognostic marker in other series (12).

Our dataset undoubtedly contained patients with an apparently LMN-only syndrome at diagnosis, variably termed progressive muscular atrophy (PMA), or ‘flail leg’ by others’ definition when spread was to the contralateral leg (5). Estimates of the prevalence of PMA within the wider entity of ALS range widely, and there is undoubtedly subclinical UMN involvement pathologically in many such cases (13). At present we do not believe there is clear evidence for this phenotype having a distinct prognostic profile in an analogous way to PLS patients, and we did not attempt to exclude those with apparent LMN-only signs at diagnosis.

Gowers, as far back as 1891, commented, in an entirely non-statistical way, that the early rate of progression seemed to remain consistent: “When the progress at the commencement is rapid it usually continues rapid…when it begins slowly, it is usually slow throughout.” (14). Among the most commonly reported predictors of longer survival in ALS to date are: limb-(rather than bulbar-)onset disease, younger age at symptom onset (<50 years), slower early rate of progression using functional measures, and longer ‘diagnostic latency’ (12). With respect to the latter, earlier diagnosis within a specialist ALS clinic augurs worse prognosis, as it is a surrogate for a rapid rate of progression in aggressive disease. Its persistence may in part reflect failure to establish an early diagnostic test for ALS, as well as the insidious nature of its presentation clinically.

Our study demonstrated an adverse effect of taking riluzole in Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, which we believe to be spurious. In our series, patients taking riluzole had a shorter diagnostic latency (i.e. typically more rapidly progressing disease) than those who did not take riluzole (mean, 16 months versus 30 months; p < 0.001). Our use of multivariate Cox modelling would support this confounding theory where no independent adverse effect of riluzole use was then observed.

This type of prognostic modelling in ALS has been previously used to accurately predict survival across a range of phenotypes (15,16), acknowledging caveats over the limitations of retrospective analysis, in addition to the relatively small numbers we studied, and the subjective reporting of time of spread to another limb potentially introducing systematic error.

Specific ‘host’ disease-modulating factors as a substrate for prognostic heterogeneity in ALS remain elusive. Inflammatory responses have been demonstrated in vivo (17), but it is unclear whether these are primary or secondary (and so, protective or adverse). Patients homozygous for the ‘D90A’ superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) gene (mutations of which are associated with approximately 3% of all ALS cases) consistently develop a lower limb-onset disease that appears identical to lower limb-onset sporadic ALS cases, but with a mean survival of 13 years from symptom onset (18). Evidence from neurophysiology (19,20) and neuroimaging (21) suggests that the basis for this prolonged survival may lie in the relative preservation of ‘protective’ GABA-ergic inhibitory interneuronal influences, but this remains to be proven.

In summary, lower limb-onset ALS has the potential to be a slowly progressive condition whether there is initial spread to the contralateral limb (as described in the ‘flail leg’ phenotype) or spread to the ipsilateral arm. The time taken for progression of symptoms beyond the limb of initial onset is a major determinant of overall survival, and can be used to facilitate patient decision-making and plan care more effectively.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the staff of the Oxford and Sheffield MND Care and Research Centres (who both receive funding from the UK MND Association), for their ongoing work in the care of ALS patients. MRT is supported by the MRC/MNDA Lady Edith Wolfson Clinician Scientist Fellowship, and AB is supported by an NIHR Clinical Training Lectureship.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Logroscino G, Traynor BJ, Hardiman O, Chio A, Couratier P, Mitchell JD, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: new evidence and unsolved issues. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:6–11. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.104828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner MR, Parton MJ, Shaw CE, Leigh PN, Al Chalabi A. Prolonged survival in motor neuron disease: a descriptive study of the Kings’ database 1990–2002. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:995–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu MT, Ellis CM, Al Chalabi A, Leigh PN, Shaw CE. Flail arm syndrome: a distinctive variant of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:950–1. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.6.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappellari A, Ciammola A, Silani V. The pseudopolyneuritic form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Patrikios’ disease) Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;48:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijesekera LC, Mathers S, Talman P, Galtrey C, Parkinson MH, Ganesalingam J, et al. Natural history and clinical features of the flail arm and flail leg ALS variants. Neurology. 2009;72:1087–94. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345041.83406.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravits J, Paul P, Jorg C. Focality of upper and lower motor neuron degeneration at the clinical onset of ALS. Neurology. 2007;68:1571–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260965.20021.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravits J, Laurie P, Fan Y, Moore DH. Implications of ALS focality: rostral-caudal distribution of lower motor neuron loss post mortem. Neurology. 2007;68:1576–82. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261045.57095.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravits JM, La Spada AR. ALS motor phenotype heterogeneity, focality, and spread: deconstructing motor neuron degeneration. Neurology. 2009;73:805–11. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b6bbbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks BR, Sanjak M, Belden D, Juhazs-Poscine K, Waclawik A, Brown RH, Jr, et al. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. Martin Dunitz; London: 2000. Natural history of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: impairment, disability, handicap; pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wohlfart G. Collateral regeneration in partially denervated muscles. Neurology. 1958;8:175–80. doi: 10.1212/wnl.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon PH, Cheng B, Katz IB, Pinto M, Hays AP, Mitsumoto H, et al. The natural history of primary lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2006;66:647–53. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000200962.94777.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chio A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O, Swingler R, Mitchell D, Beghi E, et al. Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10:310–23. doi: 10.3109/17482960802566824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ince PG, Evans J, Knopp M, Forster G, Hamdalla HH, Wharton SB, et al. Corticospinal tract degeneration in the progressive muscular atrophy variant of ALS. Neurology. 2003;60:1252–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000058901.75728.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gowers WR. Diseases Of The Nervous System. P. Blakiston, Son & Co.; Philadelphia: 1893. p. 483. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haverkamp LJ, Appel V, Appel SH. Natural history of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a database population. Validation of a scoring system and a model for survival prediction. Brain. 1995;118:707–19. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner MR, Bakker M, Sham P, Shaw CE, Leigh PN, Al-Chalabi A. Prognostic modelling of therapeutic interventions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2002;3:15–21. doi: 10.1080/146608202317576499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner MR, Cagnin A, Turkheimer FE, Miller CC, Shaw CE, Brooks DJ, et al. Evidence of widespread cerebral microglial activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an [(11)C](R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen PM, Forsgren L, Binzer M, Nilsson P, Ala-Hurula V, Keranen ML, et al. Autosomal recessive adult-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with homozygosity for Asp90Ala Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase mutation. A clinical and genealogical study of 36 patients. Brain. 1996;119:1153–72. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.4.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber M, Eisen A, Stewart HG, Andersen PM. Preserved slow conducting corticomotoneuronal projections in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with autosomal recessive D90A Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase mutation. Brain. 2000;123:1505–15. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.7.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner MR, Osei-Lah AD, Hammers A, Al Chalabi A, Shaw CE, Andersen PM, et al. Abnormal cortical excitability in sporadic but not homozygous D90A SOD1 ALS. J Neurol NeurosurgPsychiatry. 2005;76:1279–85. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.054429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner MR, Hammers A, Al Chalabi A, Shaw CE, Andersen PM, Brooks DJ, et al. Distinct cerebral lesions in sporadic and ‘D90A’ SOD1 ALS: studies with [11C]flumazenil PET. Brain. 2005;128:1323–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]