Abstract

We use quantized molecular dynamics simulations to characterize the role of enzyme vibrations in facilitating dihydrofolate reductase hydride transfer. By sampling the full ensemble of reactive trajectories, we are able to quantify and distinguish between statistical and dynamical correlations in the enzyme motion. We demonstrate the existence of nonequilibrium dynamical coupling between protein residues and the hydride tunneling reaction, and we characterize the spatial and temporal extent of these dynamical effects. Unlike statistical correlations, which give rise to nanometer-scale coupling between distal protein residues and the intrinsic reaction, dynamical correlations vanish at distances beyond 4–6 Å from the transferring hydride. This work finds a minimal role for nonlocal vibrational dynamics in enzyme catalysis, and it supports a model in which nanometer-scale protein fluctuations statistically modulate—or gate—the barrier for the intrinsic reaction.

Keywords: enzyme dynamics, hydrogen tunneling, path integral, ring polymer molecular dynamics

Protein motions are central to enzyme catalysis, with conformational changes on the micro- and millisecond timescale well-established to govern progress along the catalytic cycle (1, 2). Less is known about the role of faster, atomic-scale fluctuations that occur in the protein environment of the active site. The textbook view of enzyme-catalyzed reaction mechanisms neglects the functional role of such fluctuations and describes a static protein environment that both scaffolds the active-site region and reduces the reaction barrier (3). This view has grown controversial amid evidence that active-site chemistry is coupled to motions in the enzyme (4–6), and it has been explicitly challenged by recent proposals that enzyme-catalyzed reactions are driven by vibrational excitations that channel energy into the intrinsic reaction coordinate (7, 8) or promote reactive tunneling (9, 10). In the following, we combine quantized molecular dynamics and rare-event sampling methods to determine the mechanism by which protein motions couple to reactive tunneling in dihydrofolate reductase and to clarify the role of nonequilibrium vibrational dynamics in enzyme catalysis.

Manifestations of enzyme motion include both statistical and dynamical correlations. Statistical correlations are properties of the equilibrium ensemble and describe, for example, the degree to which fluctuations in the spatial position of one atom are influenced by fluctuations in another; these correlations govern the free-energy (FE) landscape and determine the transition state theory kinetics of the system (6). Dynamical correlations are properties of the time-evolution of the system and describe coupling between inertial atomic motions, as in a collective vibrational mode. Compelling evidence for long-ranged (i.e., nanometer-scale) networks of statistical correlations in enzymes emerges from genomic analysis (11), molecular dynamics simulations (11–13), and kinetic studies of double-mutant enzymes (14–16). But the role of dynamical correlations in enzyme catalysis remains unresolved (4, 5, 7, 17, 18), with experimental and theoretical results suggesting that the intrinsic reaction is activated by vibrational modes involving the enzyme active site (9, 19, 20) and more distant protein residues (7, 8, 21). The degree to which enzyme-catalyzed reactions are coupled to the surrounding protein environment, and the lengthscales and timescales over which such couplings persist, are central questions in the understanding, regulation, and de novo design of biological catalysts (22).

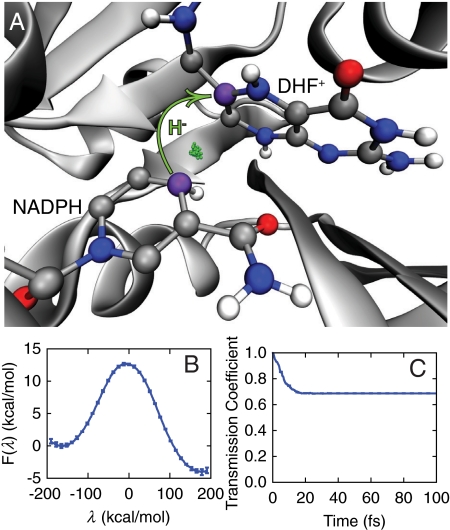

Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) is an extensively studied prototype for protein motions in enzyme catalysis. It catalyzes reduction of the 7,8-dihydrofolate (DHF) substrate via hydride transfer from the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) cofactor (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). We investigate this intrinsic reaction using ring polymer molecular dynamics (RPMD) (23, 24), a recently developed path-integral method that enables inclusion of nuclear quantization effects, such as the zero-point energy and tunneling, in the dynamics of the transferring hydride. RPMD simulations with over 14,000 atoms are performed using explicit solvent and using an empirical valence bond (EVB) potential to describe the potential energy surface for the transferring hydride; the EVB potential is obtained from an effective Hamiltonian matrix, with diagonal elements (Vr(x) and Vp(x)) corresponding to the potential energy for the reactant and product bonding connectivities and with the constant off-diagonal matrix element fit to the experimental rate (11, 25). The vector x includes the position of the quantized hydride and all classical nuclei in the system. The EVB potential employed here was chosen for consistency with earlier simulation studies of DHFR (11, 26); although the mechanistic issues addressed in this study are not expected to be highly sensitive to the details of the potential energy surface, it should be noted that more accurate electronic structure theory methods for describing the enzyme potential energy surface, including the combined quantum mechanical and classical mechanical (QM/MM) method, are available and widely used in enzyme simulations.

Fig. 1.

The hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by DHFR. (A) The active site with the hydride (green) shown in the ring-polymer representation of the quantized MD and the donor and acceptor C atoms in purple. (B) The quantized free-energy profile for the reaction. (C) The time-dependent transmission coefficient corresponding to the dividing surface at λ(x) = -4.8 kcal/mol.

The thermal reaction rate is calculated from the product of the Boltzmann-weighted activation FE and the reaction transmission coefficient (24), both of which are calculated in terms of the dividing surface λ(x) = -4.8 kcal/mol where λ(x) = Vr(x) - Vp(x). The FE surface F(λ) is obtained using over 120 ns of RPMD sampling (Fig. 1B), and the transmission coefficient is obtained from over 5,000 RPMD trajectories that are released from the Boltzmann distribution constrained to the dividing surface (Fig. 1C). In contrast to mixed quantum-classical and transition state theory methods, RPMD yields reaction rates and mechanisms that are formally independent of the choice of dividing surface or any other reaction coordinate assumption (24). Furthermore, the RPMD method enables generation of the ensemble of reactive, quantized molecular dynamics trajectories, which is essential for the following analysis of dynamical correlations. Calculation details, including a description of the rare-event sampling methodology used to generate the unbiased ensemble of reactive trajectories (27, 28), are provided in Materials and Methods below.

Results and Discussion

The time-dependence of the transmission coefficient in Fig. 1C confirms that reactive trajectories commit to the reactant or product basins within 25 fs. The near-unity value of this transmission coefficient at long times indicates that recrossing of the dividing surface in reactive trajectories is a modest effect, although it is fully accounted for in this study, and it confirms that the collective variable λ(x) provides a good measure of progress along the intrinsic reaction. We find that quantization of the hydride lowers the FE barrier by approximately 3.5 kcal/mol (Fig. S2), in agreement with earlier work (29, 30).

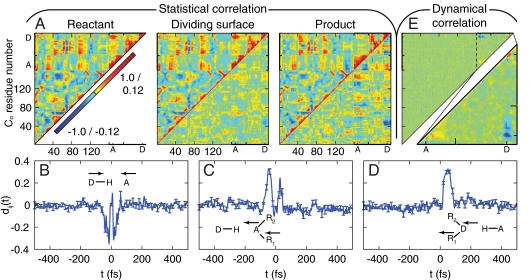

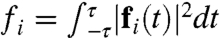

Statistical correlations among the protein and enzyme active-site coordinates are shown in Fig. 2A. The normalized covariance among atom position fluctuations, cij = Cij/(CiiCjj)1/2 such that

| [1] |

is plotted for the Boltzmann distribution in the reactant, dividing surface, and product regions. The figure shows correlations among the protein α-carbons and the heavy atoms of the substrate and cofactor; the corresponding all-atom correlation plots are provided in Fig. S3. As has been previously and correctly emphasized (11, 29, 30), structural fluctuations in the active-site and distal protein residues are richly correlated within each region, which contributes to nonadditive effects in the kinetics of DHFR mutants (14, 31). Furthermore, the network of correlations varies among the three ensembles, indicating that fluctuations in distal protein residues respond to the adiabatic progress of the hydride from reactant to product. However, these time-averaged quantities do not address the role of dynamical correlations between the transferring hydride and its environment, which depend on the hierarchy of timescales for motion in the system.

Fig. 2.

Statistical and dynamical correlations among enzyme motions during the intrinsic reaction. (A) (Upper triangles) The covariance cij among position fluctuations in DHFR, plotted for the reactant, dividing surface, and product regions. Protein residues are indexed according to [Protein Data Bank (PDB) 1RX2]; substrate and cofactor regions are indicated by the hydride acceptor A and donor D atoms, respectively. (Lower triangles) The difference with respect to the plot for the reactant basin. (B–D) The dynamical correlation measure dij(t) for (B) the donor and acceptor atom pair, (C) the substrate-based C7 and acceptor atom pair, and (D) the cofactor-based CN3 and donor atom pair. Results for additional atom pairs are presented in Fig. S5. (E) (Upper triangle) The integrated dynamical correlation measure dij, indexed as in (A). Significant dynamical correlations appear primarily in the substrate and cofactor regions, which are enlarged in the lower triangle.

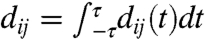

To characterize dynamical correlations in the intrinsic reaction, we introduce a measure of velocity cross-correlations in the reactive trajectories, dij(t) = Dij(t)/(Dii(t)Djj(t))1/2 such that

| [2] |

Here,  denotes an average over the nonequilibrium ensemble of phase-space points that lie on reactive trajectories that crossed the dividing surface some time t earlier and subsequently terminate in the product basin. This quantity, which vanishes for the equilibrium ensemble, reports on the degree to which atoms move in concert during the intrinsic reaction step. Fig. 2 B–D show dij(t) for several atomic pairs in the active site. Negative dynamical correlations are seen between the donor and acceptor C atoms (Fig. 2B), which move in opposite directions (first approaching each other, then moving apart) during the hydride transfer. Similarly, positive correlations are seen between atom pairs on the cofactor (Fig. 2C) and on the substrate (Fig. 2D) that move in concert as the hydride is transferred. In each case, the primary features of the correlation decay within τ = 100 fs.

denotes an average over the nonequilibrium ensemble of phase-space points that lie on reactive trajectories that crossed the dividing surface some time t earlier and subsequently terminate in the product basin. This quantity, which vanishes for the equilibrium ensemble, reports on the degree to which atoms move in concert during the intrinsic reaction step. Fig. 2 B–D show dij(t) for several atomic pairs in the active site. Negative dynamical correlations are seen between the donor and acceptor C atoms (Fig. 2B), which move in opposite directions (first approaching each other, then moving apart) during the hydride transfer. Similarly, positive correlations are seen between atom pairs on the cofactor (Fig. 2C) and on the substrate (Fig. 2D) that move in concert as the hydride is transferred. In each case, the primary features of the correlation decay within τ = 100 fs.

Fig. 2E summarizes the extent of dynamical correlations throughout the enzyme system in terms of  . Only atoms in the substrate and cofactor regions (Fig. 2E, lower triangle) and a small number of protein atoms in the active-site region exhibit appreciable signal. The same conclusions are reached upon integrating the absolute value of the dij(t) (Fig. S4), emphasizing that this lack of signal in the protein residues is not simply due to the time integration. Instead, Fig. 2E reveals that the dynamical correlations between distal protein residues and the intrinsic reaction do not exist on any timescale. We also provide measures for dynamical correlations that are nonlocal in time (Fig. S5) and for dynamical correlations among perpendicular motions (Fig. S6), but the following conclusion is unchanged. The extensive network of statistical correlations (Fig. 2A) is neither indicative of, nor accompanied by, an extensive network of dynamical correlations during the intrinsic reaction (Fig. 2E).

. Only atoms in the substrate and cofactor regions (Fig. 2E, lower triangle) and a small number of protein atoms in the active-site region exhibit appreciable signal. The same conclusions are reached upon integrating the absolute value of the dij(t) (Fig. S4), emphasizing that this lack of signal in the protein residues is not simply due to the time integration. Instead, Fig. 2E reveals that the dynamical correlations between distal protein residues and the intrinsic reaction do not exist on any timescale. We also provide measures for dynamical correlations that are nonlocal in time (Fig. S5) and for dynamical correlations among perpendicular motions (Fig. S6), but the following conclusion is unchanged. The extensive network of statistical correlations (Fig. 2A) is neither indicative of, nor accompanied by, an extensive network of dynamical correlations during the intrinsic reaction (Fig. 2E).

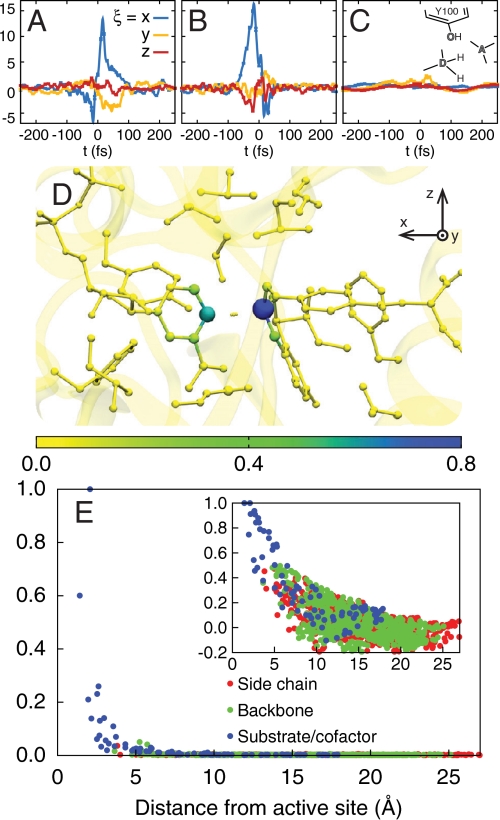

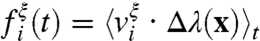

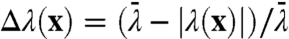

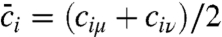

A combined measure of the dynamical correlation between a given atom and the intrinsic reaction event can be obtained from the nonequilibrium ensemble average of velocities in the reactive trajectories. Specifically, we consider  , where ξ∈{x,y,z} indicates the component of the velocity, the filter

, where ξ∈{x,y,z} indicates the component of the velocity, the filter  selects configurations in the region of the dividing surface, and

selects configurations in the region of the dividing surface, and  is the average magnitude of λ(x) in the reactant and product regions. Each component of fi(t) vanishes trivially at equilibrium. Fig. 3 A–C presents the measure for various atoms in the active-site region. The donor and acceptor C atoms (Fig. 3 A and B) are both strongly correlated with the dynamics of the intrinsic reaction, whereas the O atom in the Y100 residue of the active site (Fig. 3C) reveals smaller, but nonzero, signatures of dynamical correlation. Fig. 3D presents

is the average magnitude of λ(x) in the reactant and product regions. Each component of fi(t) vanishes trivially at equilibrium. Fig. 3 A–C presents the measure for various atoms in the active-site region. The donor and acceptor C atoms (Fig. 3 A and B) are both strongly correlated with the dynamics of the intrinsic reaction, whereas the O atom in the Y100 residue of the active site (Fig. 3C) reveals smaller, but nonzero, signatures of dynamical correlation. Fig. 3D presents  for each atom, summarizing the degree to which all atoms in the active site exhibit dynamical correlations, and Fig. 3E compares the correlation lengthscales in the enzyme. The main panel in Fig. 3E presents fi as a function of the distance of heavy atoms from the midpoint of the hydride donor and acceptor, and the inset similarly presents the distance dependence of the statistical correlation measure

for each atom, summarizing the degree to which all atoms in the active site exhibit dynamical correlations, and Fig. 3E compares the correlation lengthscales in the enzyme. The main panel in Fig. 3E presents fi as a function of the distance of heavy atoms from the midpoint of the hydride donor and acceptor, and the inset similarly presents the distance dependence of the statistical correlation measure  , where cij is defined previously and where indices μ and ν label the donor and acceptor carbon atoms, respectively. Whereas the statistical correlations reach the nanometer lengthscale and involve the protein environment, dynamical correlations are extremely local in nature and primarily confined to the enzyme substrate and cofactor.

, where cij is defined previously and where indices μ and ν label the donor and acceptor carbon atoms, respectively. Whereas the statistical correlations reach the nanometer lengthscale and involve the protein environment, dynamical correlations are extremely local in nature and primarily confined to the enzyme substrate and cofactor.

Fig. 3.

The dynamical correlation measure  , plotted for (A) the donor atom, (B) the acceptor atom, and (C) the side-chain O atom in the Y100 residue of the active site. (D) The size and color of atoms in the active-site region are scaled according to the integrated dynamical correlation measure, fi. (E) (Main panel) The integrated dynamical correlation measure, fi, as a function of the distance of atom i from the midpoint of the donor and acceptor atoms. (Inset) The statistical correlation measure,

, plotted for (A) the donor atom, (B) the acceptor atom, and (C) the side-chain O atom in the Y100 residue of the active site. (D) The size and color of atoms in the active-site region are scaled according to the integrated dynamical correlation measure, fi. (E) (Main panel) The integrated dynamical correlation measure, fi, as a function of the distance of atom i from the midpoint of the donor and acceptor atoms. (Inset) The statistical correlation measure,  , is similarly presented. Atoms corresponding to the protein side chains, the protein backbone, and the substrate/cofactor regions are indicated by color. Values presented in part A are in units of nm/ps, and values in parts D and E are normalized to a maximum of unity. The estimated error in part E is smaller than the dot size.

, is similarly presented. Atoms corresponding to the protein side chains, the protein backbone, and the substrate/cofactor regions are indicated by color. Values presented in part A are in units of nm/ps, and values in parts D and E are normalized to a maximum of unity. The estimated error in part E is smaller than the dot size.

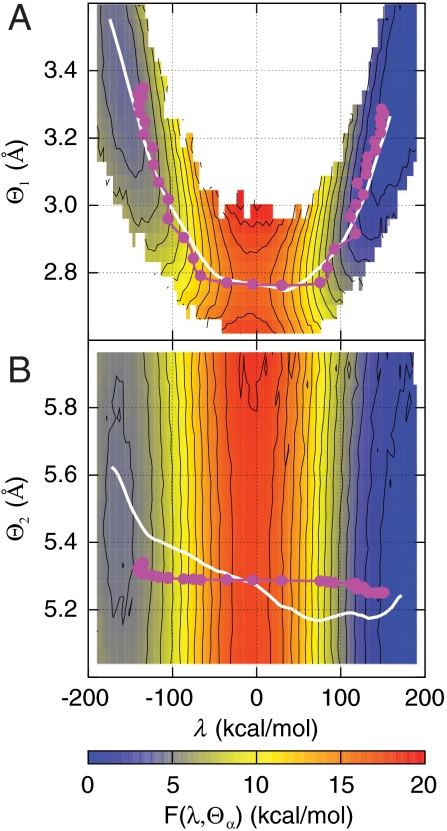

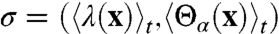

Fig. 4 illustrates that dynamical correlations in the intrinsic reaction are limited by disparities in the relative timescales for enzyme motion. The figure presents two-dimensional projections of the FE surface, F(λ,Θα), where α∈{1,2}, Θ1(x) is the distance between hydride donor and acceptor atoms, and Θ2(x) is the separation between active-site protein atoms I14 Cδ and Y100 O (side chain). Overlaid on the surfaces are the minimum FE pathway between the reactant and product basins, s, and the time-parameterized pathway followed by the ensemble of reactive trajectories,  . Nonzero slope in s indicates statistical correlation of Θα with λ, whereas the same feature in σ indicates that the dynamics of Θα and λ are dynamically correlated. Fig. 4A confirms that the donor-acceptor distance is both statistically and dynamically correlated with the intrinsic reaction. In contrast, Fig. 4B reveals significant statistical correlation between Θ2 and the intrinsic reaction, but the reactive trajectories traverse the dividing surface region on a timescale that is too fast to dynamically couple to the protein coordinate.

. Nonzero slope in s indicates statistical correlation of Θα with λ, whereas the same feature in σ indicates that the dynamics of Θα and λ are dynamically correlated. Fig. 4A confirms that the donor-acceptor distance is both statistically and dynamically correlated with the intrinsic reaction. In contrast, Fig. 4B reveals significant statistical correlation between Θ2 and the intrinsic reaction, but the reactive trajectories traverse the dividing surface region on a timescale that is too fast to dynamically couple to the protein coordinate.

Fig. 4.

Minimum free-energy pathways (s, white) and the mean pathway of the reactive trajectories (σ, magenta) overlay two-dimensional projections of the free-energy landscape, F(λ,Θα). (A) F(λ,Θ1), where Θ1 is the distance between the hydride donor and acceptor atoms. (B) F(λ,Θ2), where Θ2 is the distance between side-chain atoms I14 Cδ and Y100 O in the active-site residues. The dots in the magenta curves indicate 5 fs increments in time. Nonzero slope in s and σ indicates statistical and dynamical correlations, respectively.

The results presented here complement previous theoretical efforts to illuminate the role of protein motions in enzyme catalysis. For example, Neria and Karplus (32) used transmission coefficient calculations and constrained molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories to determine that the protein environment in triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) is essentially rigid (i.e., dynamically unresponsive) on the timescale of the intrinsic reaction dynamics; this finding is consistent with the lack of long-lengthscale dynamical correlations reported in the current study. Furthermore, Truhlar and coworkers (33, 34) and Karplus and Cui (35) both demonstrated that quasi-classical tunneling coefficients for hydrogen transfer evaluated at instantaneous enzyme configurations in the transition state region fluctuate significantly with donor-acceptor motions and other local active-site vibrations, which is likely consistent with the direct observation of short-lengthscale dynamical correlations reported here. However, by using quantized molecular dynamics to sample the ensemble of reactive trajectories in DHFR catalysis and to perform nonequilibrium ensemble averages that directly probe dynamical correlation, we provide a framework for strengthening and generalizing these earlier analyses. In particular, the current approach avoids transition state theory approximations by providing a rigorous statistical mechanical treatment of the ensemble of reactive trajectories, it allows for the natural characterization of lengthscales and timescales over which dynamical correlations persist, and it seamlessly incorporates dynamical effects due to both nuclear quantization and trajectory recrossing. We expect this approach to prove useful in future studies of dynamics in other enzymes, which will be necessary to confirm the generality of the conclusions drawn here.

Concluding Remarks

The physical picture that emerges from this analysis is one in which the intrinsic reaction involves a small, localized group of atoms that are dynamically uncoupled from motions in the surrounding protein environment. As in the canonical theories for electron and proton transfer in the condensed phase (36, 37), the strongly dissipative protein environment merely gates the fast dynamics in the active site. This view reconciles the observed kinetic effects of distal enzyme mutations (14, 15) with evidence for short-ranged dynamical correlations in the active site (9, 19, 20), and it supports a unifying theoretical perspective in which slow, thermal fluctuations in the protein modulate the instantaneous rate for the intrinsic reaction (4, 7, 17, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41). Furthermore, the work presented here provides clear evidence against the proposed role of nonlocal, rate-promoting vibrational dynamics in the enzyme (8), and it reveals the strikingly short lengthscales over which nonequilibrium protein dynamics couples to the intrinsic reaction. The combination of quantized molecular dynamics methods (24) with trajectory sampling methods (28) provides a useful approach for characterizing mechanistic features of reactions involving significant quantum tunneling effects. These findings for the case of the DHFR enzyme, a good candidate for dynamical correlations because of its small size and strong network of statistical correlations, suggest that nonlocal dynamical correlations are neither a critical feature of enzyme catalysis nor an essential consideration in de novo enzyme design.

Materials and Methods

Calculation Details.

All simulations are performed using a modified version of the Gromacs-4.0.7 molecular dynamics package (42). Further calculation details regarding the potential energy surface, the system initialization and equilibration protocol, free-energy sampling, and dividing surface sampling are provided in SI Text, Figs. S7–S9, and Table S1.

Ring Polymer Molecular Dynamics.

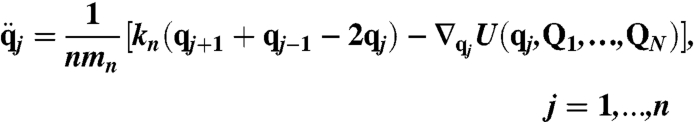

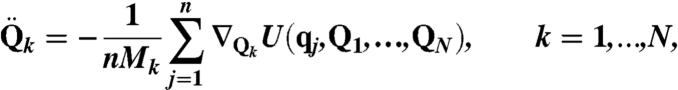

The RPMD equations of motion (23) used to simulate the dynamics of DHFR are

|

[3] |

|

[4] |

where U(q,Q1,…,QN) is the potential energy function for the system, n = 32 is the number of ring polymer beads used to quantize the hydride, qj and mn are the position and mass of the jth ring polymer bead, and q0 = qn. Similarly, N is the number of classical nuclei in the system, and Qk and Mk are the position and mass of the kth classical atom, respectively. The interbead force constant is kn = mHn2/(βℏ)2, where mH = 1.008 amu is the mass of the hydride and β = (kBT)-1 is the reciprocal temperature; a temperature of T = 300 K is used throughout the study. For dynamical trajectories, RPMD prescribes that mn = mH/n.

Calculating the Statistical Correlation Functions, cij.

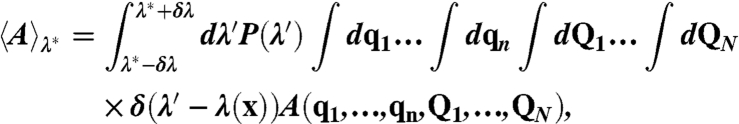

In Fig. 3A, equilibrium ensemble averages are presented for the system in the reactant region, the dividing surface region, and the product region. These ensemble averages are strictly defined using

|

[5] |

where P(λ) = exp(-βF(λ))/∫dλ′ exp(-βF(λ′)), and F(λ) is calculated using umbrella sampling, as described in SI Text. For the ensembles in the reactant, dividing surface, and product regions, we employ λ∗ = -181 kcal/mol, -7 kcal/mol, and 169 kcal/mol, respectively, and δλ = 2.5 kcal/mol.

The Transition Path Ensemble.

Reactive trajectories are generated through forward- and backward-integration of initial configurations drawn from the dividing surface ensemble with initial velocities drawn from the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution. Reactive trajectories correspond to those for which forward- and backward-integrated half-trajectories terminate on opposite sides of the dividing surface. From the 10,500 half-trajectories that are initialized on the dividing surface (i.e., 5,250 possible reactive trajectories), over 3,000 reactive RPMD trajectories are obtained. For analysis purposes, the integration of these reactive trajectories was continued for a total length of 1 ps in both the forward and backward trajectories.

The reactive trajectories that are initialized from the equilibrium Boltzmann distribution on the dividing surface must be reweighted to obtain the unbiased ensemble of reactive trajectories (i.e., the transition path ensemble) (27, 28, 43). A weighting term is applied to each trajectory α, correctly accounting for the recrossing and for the fact that the trajectories are performed in the microcanonical ensemble (27),

|

[6] |

where the sum includes all instances in which trajectory α crosses the dividing surface, and  is the velocity in the collective variable at crossing event i. We find that the relative statistical weight of all reactive trajectories that recross the dividing surface is 1.6%, emphasizing that recrossing does not play a large role in the current study.

is the velocity in the collective variable at crossing event i. We find that the relative statistical weight of all reactive trajectories that recross the dividing surface is 1.6%, emphasizing that recrossing does not play a large role in the current study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER Award (CHE-1057112) and computing resources at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center. Additionally, N.B. acknowledges an NSF graduate research fellowship, and T.F.M. acknowledges an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1106397108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Henzler-Wildman KA, et al. Intrinsic motions along an enzymatic reaction trajectory. Nature. 2007;450:838–844. doi: 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehr DD, McElheny D, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Millisecond timescale fluctuations in dihydrofolate reductase are exquisitely sensitive to the bound ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1373–1378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914163107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook PF, Cleland WW. Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanism. New York: Garland Science; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamerlin SCL, Warshel A. At the dawn of the 21st century: Is dynamics the missing link for understanding enzyme catalysis? Proteins. 2010;78:1339–1375. doi: 10.1002/prot.22654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nashine VC, Hammes-Schiffer S, Benkovic SJ. Coupled motions in enzyme catalysis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Viloca M, Gao J, Karplus M, Truhlar DG. How enzymes work: Analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science. 2004;303:186–195. doi: 10.1126/science.1088172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz SD, Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states and dynamic motion in barrier crossing. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:551–559. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machleder SQ, Pineda JRET, Schwartz SD. On the origin of the chemical barrier and tunneling in enzymes. J Phys Org Chem. 2010;23:690–695. doi: 10.1002/poc.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masgrau L, et al. Atomic description of an enzyme reaction dominated by proton tunneling. Science. 2006;312:237–241. doi: 10.1126/science.1126002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagel ZD, Klinman JP. A 21st century revisionist’s view at a turning point in enzymology. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal PK, Billeter SR, Rajagopalan PTR, Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. Network of coupled promoting motions in enzyme catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2794–2799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052005999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pang JY, Pu JZ, Gao JL, Truhlar DG, Allemann RK. Hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by hyperthermophilic dihydrofolate reductase is dominated by quantum mechanical tunneling and is promoted by both inter- and intramonomeric correlated motions. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8015–8023. doi: 10.1021/ja061585l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rod TH, Radkiewicz JL, Brooks CL. Correlated motion and the effect of distal mutations in dihydrofolate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6980–6985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230801100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong KF, Selzer T, Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. Impact of distal mutations on the network of coupled motions correlated to hydride transfer in dihydrofolate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6807–6812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408343102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Tharp S, Selzer T, Benkovic SJ, Kohen A. Effects of a distal mutation on active site chemistry. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1383–1392. doi: 10.1021/bi0518242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gira B, et al. A dynamic knockout reveals that conformational fluctuations influence the chemical step of enzyme catalysis. Science. 2011;332:234–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1198542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. Enzyme motions inside and out. Science. 2006;312:208–209. doi: 10.1126/science.1127654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Truhlar DG. Tunneling in enzymatic and nonenzymatic hydrogen transfer reactions. J Phys Org Chem. 2010;23:660–676. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pudney CR, et al. Evidence to support the hypothesis that promoting vibrations enhance the rate of an enzyme catalyzed H-tunneling reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17072–17073. doi: 10.1021/ja908469m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loveridge EJ, Tey LH, Allemann RK. Solvent effects on catalysis by Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1137–1143. doi: 10.1021/ja909353c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saen-Oon S, Quaytman-Machleder S, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Atomic detail of chemical transformation at the transition state of an enzymatic reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16543–16548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808413105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ball P. By chance, or by design? Nature. 2004;431:396–397. doi: 10.1038/431396a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craig IR, Manolopoulos DE. Quantum statistics and classical mechanics: Real time correlation functions from ring polymer molecular dynamics. J Chem Phys. 2004;121:3368–3373. doi: 10.1063/1.1777575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig IR, Manolopoulos DE. A refined ring polymer molecular dynamics theory of chemical reaction rates. J Chem Phys. 2005;123:034102. doi: 10.1063/1.1954769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warshel A, Weiss RM. An empirical valence bond approach for comparing reactions in solutions and in enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:6218–6226. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu HB, Warshel A. Origin of the temperature dependence of isotope effects in enzymatic reactions: The case of dihydrofolate reductase. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:7852–7861. doi: 10.1021/jp070938f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hummer G. From transition paths to transition states and rate coefficients. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:516–523. doi: 10.1063/1.1630572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolhuis PG, Chandler D, Dellago C, Geissler PL. Transition path sampling: Throwing ropes over rough mountain passes, in the dark. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2002;53:291–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.53.082301.113146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal PK, Billeter SR, Hammes-Schiffer S. Nuclear quantum effects and enzyme dynamics in dihydrofolate reductase catalysis. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:3283–3293. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Viloca M, Truhlar DG, Gao JL. Reaction-path energetics and kinetics of the hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by dihydrofolate reductase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13558–13575. doi: 10.1021/bi034824f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajagopalan PTR, Lutz S, Benkovic SJ. Coupling interactions of distal residues enhance dihydrofolate reductase catalysis: Mutational effects on hydride transfer rates. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12618–12628. doi: 10.1021/bi026369d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neria E, Karplus M. Molecular dynamics of an enzyme reaction: Proton transfer in TIM. Chem Phys Lett. 1997;267:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pu JZ, Ma SH, Gao JL, Truhlar DG. Small temperature dependence of the kinetic isotope effect for the hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:8551–8556. doi: 10.1021/jp051184c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pu JZ, Gao JL, Truhlar DG. Multidimensional tunneling, recrossing, and the transmission coefficient for enzymatic reactions. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3140–3169. doi: 10.1021/cr050308e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui Q, Karplus M. Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics studies of triosephosphate isomerase-catalyzed reactions: Effect of geometry and tunneling on proton-transfer rate constants. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3093–3124. doi: 10.1021/ja0118439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcus RA, Sutin N. Electron transfers in chemistry and biology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;811:265–322. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borgis D, Hynes JT. Curve crossing formulation for proton transfer reactions in solution. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:1118–1128. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knapp MJ, Klinman JP. Environmentally coupled hydrogen tunneling: Linking catalysis to dynamics. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:3113–3121. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcus RA. Enzymatic catalysis and transfers in solution. i. theory and computations, a unified view. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194504. doi: 10.1063/1.2372496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuznetsov AM, Ulstrup J. Proton and hydrogen atom tunnelling in hydrolytic and redox enzyme catalysis. Can J Chem. 1999;77:1085–1096. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szabo A, Shoup D, Northrup SH, Mccammon JA. Stochastically gated diffusion-influenced reactions. J Chem Phys. 1982;77:4484–4493. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. Gromacs 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.E W, Vanden-Eijnden E. Towards a theory of transition paths. J Stat Phys. 2006;123:503–523. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.