Abstract

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) causes a severe and often persistent arthralgic disease that is occasionally fatal. A mosquito-borne virus, CHIKV exists in enzootic, non-human primate cycles in Africa, but occasionally emerges into urban, human cycles to cause major epidemics. Between 1920 and 1950, and again in 2005, CHIKV emerged into India and Southeast Asia, where major urban epidemics ensued. Unlike the early introduction, the 2005 emergence was accompanied by an adaptive mutation that allowed CHIKV to exploit a new epidemic vector, Aedes albopictus, via an A226V substitution in the E1 envelope glycoprotein. However, recent reverse genetic studies indicate that lineage-specific epistatic restrictions can prevent this from exerting its phenotype on mosquito infectivity. Thus, the A. albopictus-adaptive A226V substitution that is facilitating the dramatic geographic spread CHIKV epidemics, was prevented for decades or longer from being selected in most African enzootic strains as well as in the older endemic Asian lineage.

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is one of 29 species in the Family Togaviridae, genus Alphavirus [1]. Many alphaviruses found in the New World can cause encephalitis in humans and equids, while the majority of the Old World alphaviruses including CHIKV cause a human syndrome typically characterized by the triad of rash, arthralgia and fever [2]. The most important of these Old World alphaviruses are found in the Semliki forest antigenic complex; in addition to CHIKV, this complex includes o’nyong-nyong, Ross River and Mayaro viruses, important pathogens in Africa, Australia and South America, respectively.

a. Genome organization and viral replication

The single stranded, positive sense RNA genome of CHIKV is about 11.7 kb and encodes 2 open reading frames (ORF), flanked by 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions. The 5’ ORF is translated from genomic RNA by a cap-dependent mechanism, which results in the formation of 4 nonstructural proteins (nsP1–4) responsible for cytoplasmic RNA replication and modulation of cellular antiviral responses [3].. The 3’ ORF is translated from a subgenomic RNA, which is also capped, to yield 3 major structural virus proteins (capsid, E2 and E1 envelope glycoproteins). E2 is primarily responsible for interactions with cellular receptors and E1 promotes virus fusion within endosomes of target cells. After translation the E2 precursor, p62, forms heterodimers in the endoplasmic reticulum with E1 that transit though the secretory pathway to the plasma membrane, where they interact with nucleocapsids to initiate budding of icosahedral virions (T=4) [4]. CHIKV entry into cells occurs via a pH-dependent mechanism in endosomes, which culminates in fusion pore formation and release of the nucleocapsid into the cytosol.[5].

b. Chikungunya disease

Human CHIKV infection is usually symptomatic, with an acute onset of fever, followed by rash and arthralgia in the majority of cases. Attack rates often exceed 50% during epidemics. The arthralgia is especially painful and debilitating, resulting in major losses in productivity in addition to direct morbidity; in one part of India, CHIKV infection was responsible for 69% of the total disability adjusted life years (DALY), a measure of debilitating disease burden [6]. Although most persons recover completely within a few weeks of infection, persistent arthralgia as well as neurological manifestations lasting more than one year have been documented [7]. Fatalities following CHIKV infection have been reported on Réunion Island as well as in India and Italy [8], including fatal neurologic disease [9,10]. Although many of these cases probably had underlying medical conditions that may have exacerbated disease, excess deaths reported in several locations suggest that CHIKV infection is a major factor in many fatal outcomes [8,11,12].

c. Ecology and epidemiology

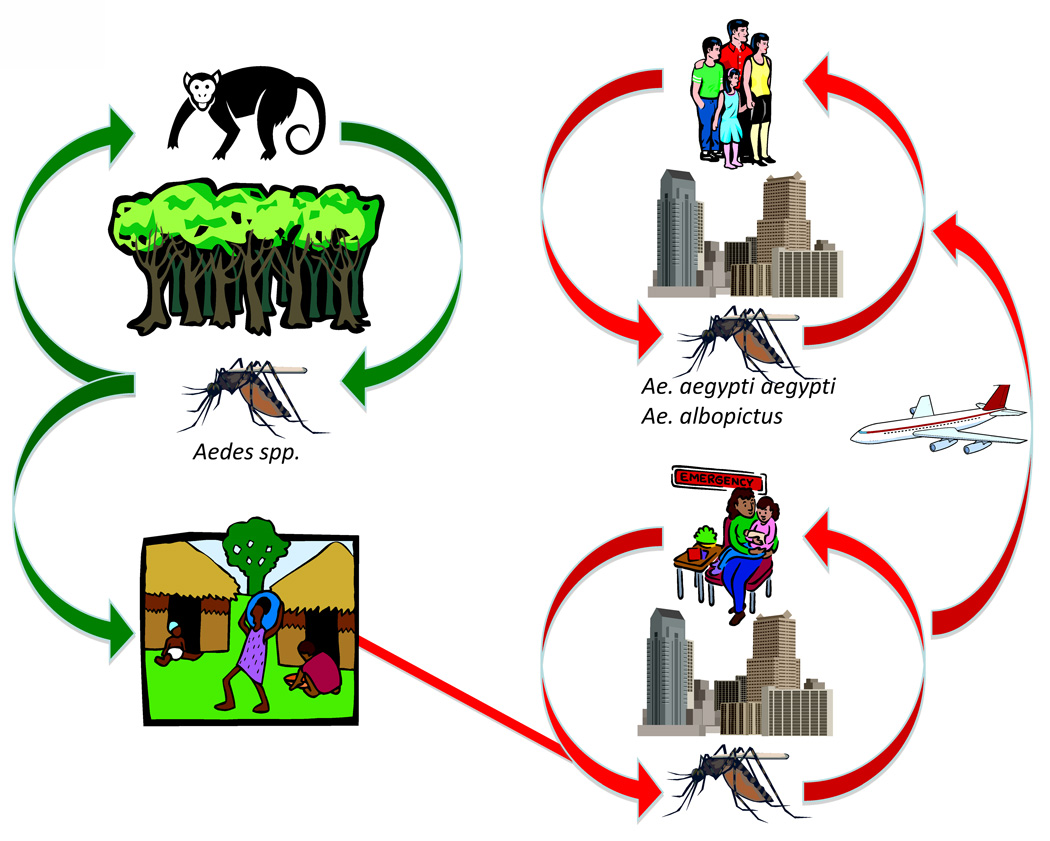

CHIKV is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa and South-East Asia. In Africa, CHIKV circulates primarily in a sylvatic, enzootic cycle, which leads to occasional spillover infections of humans, including small outbreaks in rural areas. Human migration probably results in urban introduction, where the highly anthropophilic A. aegypti aegypti and recently introduced A. albopictus can sustain transmission in a mosquito-human cycle (Fig. 1). CHIKV circulation has been documented in numerous African countries (Fig. 2), and typically coincides with periods of heavy rains and increased mosquito densities [13]. Non-human primates are believed to be the primary CHIKV reservoir hosts, and the 5–10-year periodicity of virus activity in a given locality is hypothesized to depend on oscillations in monkey herd immunity [14,15]. Entomological studies indicate that sylvatic, primatophilic A. furcifer-taylori, A. africanus, A. luteocephalus and A. neoafricanus serve as principal enzootic CHIKV vectors. A. africanus appears to be most important in central Africa, whereas A. furcifer is more important in southern and western Africa [14,15].

Fig. 1.

Cartoon depicting the transmission cycles of chikungunya virus.

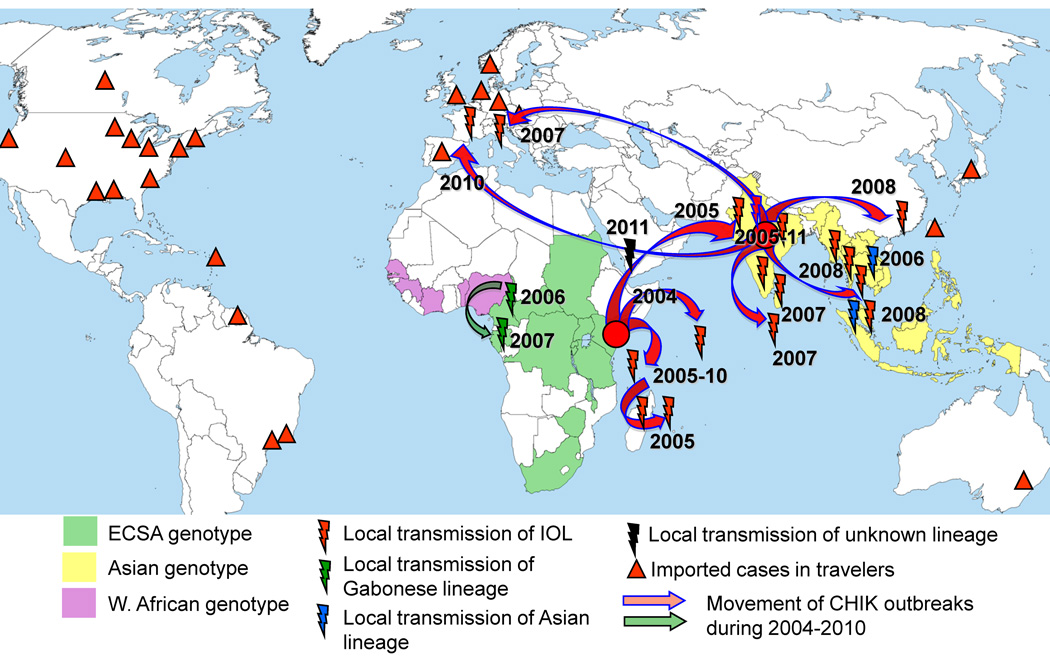

Fig. 2.

Map showing the geographic distribution of CHIKV genotypes and the movement of CHIK outbreaks during 2004–2011. Triangles show countries with CHIKV importation via infected travelers. Based on references [13,15,30,33,53], data from Pubmed, PromedMail.org the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov).

Historically, CHIKV maintenance in Asia was primarily associated only with a human-A. aegypti urban cycle, and virus persistence was thought to result from continuous CHIKV introductions into new areas with immunologically naïve populations [13,16]. However, several recent studies suggest that sylvatic, zoonotic transmission cycles could also exist in Asia [17].

II. Evolution

a. History of CHIK

CHIKV was discovered in 1953 during a massive outbreak of febrile illness in Tanzania. The name chikungunya is derived from the Makonde word, and describes the stiffness in body movement associated with arthralgic symptoms [15]. Since its isolation, CHIK outbreaks have been repeatedly documented in African and Southeast Asian countries (reviewed in [13]) at intervals of 2–20 years. Retrospective case studies by Carey implicated CHIKV in a 1779 outbreak of febrile illness in Batavia-Jakarta, which previously was thought to be caused by dengue virus. Due its clinical similarities to dengue, CHIK is frequently misdiagnosed, and its actual impact in tropical regions is greatly underestimated [18]. Prior to the re-emergence of CHIKV in 2004 in Kenya, the most recent CHIKV outbreaks were documented in 1999–2000 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with 50,000 infections [19], followed by a 2001–2003 epidemic in Indonesia [20].

b. Phylogenetic studies of CHIKV

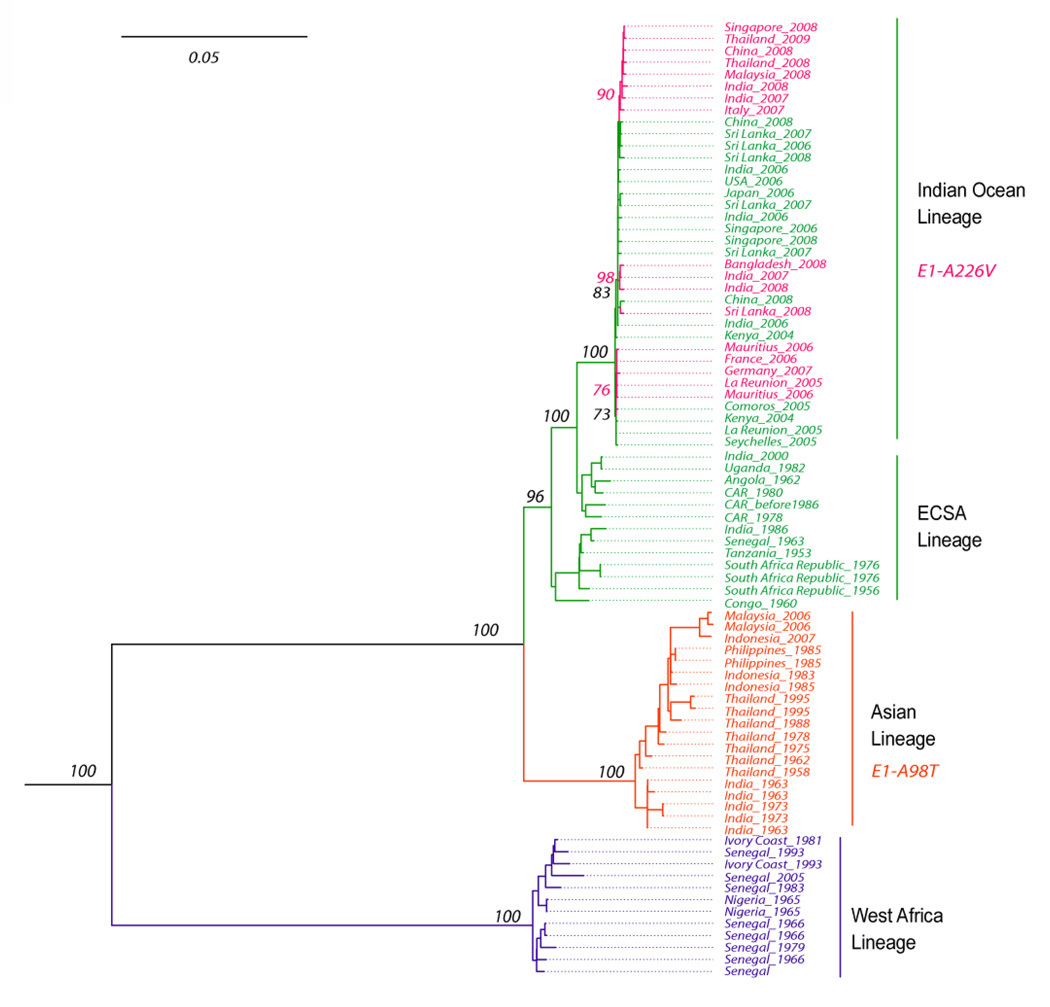

The first phylogenetic analysis of CHIKV using partial nucleotide sequences of the E1 gene among 18 strains revealed the existence of two principal lineages; one was sampled from western Africa and the second included all isolates from southern and eastern Africa, as well as all from Asia [21]. These results supported the hypothesis that CHIKV originated in Africa and was introduced into Asia from eastern Africa. The closely related o’nyong-nyong virus, previously hypothesized to be a mutant strain of CHIKV, was determined to be a genetically distinct virus species.

Since the major CHIK outbreak began in 2004, additional phylogenetic studies have been performed, most focusing on recent isolates. The first examined CHIKV isolates from 127 patients infected in Réunion, Seychelles, Mauritius, Madagascar, and Mayotte islands in the Indian Ocean, and concluded that these outbreaks were initiated by a CHIKV strain that originated in East Africa [22]. Importantly, microevolution during the outbreaks suggested that an amino acid substitution A226V in the E1 glycoprotein, in a region known to be involved in viral entry via fusion with endosomal membranes, might have been selected during epidemic transmission. Sequencing and phylogenetic analyses of 2005–2006 CHIKV strains from the beginning of the Indian epidemic also demonstrated a close relationship to East African strains, as well as to isolates from the Indian ocean islands, but without the A226V substitution [23]. However, this substitution was subsequently identified in India during 2007, demonstrating convergent evolution of CHIKV strains [24]. Later studies indicated that both Indian and Indian Ocean outbreaks originated from strains circulating in coastal Kenya in 2004 [25]. Recently, CHIKV strains isolated in Southeast Asia have been shown phylogenetically to have originated in India [26,27].

The most comprehensive phylogenetic study of CHIKV involved the analysis of complete open reading frame sequences for both the nonstructural and structural polyproteins [28]. An updated tree including 10 new sequences sampled from 2007–2009 is shown in Fig. 3. This analysis confirmed 2 major enzootic CHIKV lineages in Africa: western, and East/Central/South African (ECSA), and concluded that CHIKV was introduced from eastern Africa into Asia ca. 1920–1950. The more recent Indian Ocean and Indian epidemic strains emerged independently from the mainland of East Africa. Significantly higher rates of nucleotide substitution were inferred during urban compared to enzootic transmission, suggesting differences in extrinsic incubation times, transmission frequency, and/or transovarial transmission between the two cycles [28].

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree derived from all complete genomic CHIKV sequences available in the GenBank library, excluding some early, high passage isolates and a 2000 Indian isolate of suspected origin [28].

III. Epidemic emergence

a. History of the 2004 emergence

In 2004, CHIKV began an unprecedented global expansion in a series of epidemics probably involving 5–10 million people [29], and putting hundreds of millions at risk (Fig. 2). The evolutionary studies described above demonstrated that these epidemics can be traced to at least 3 independent CHIKV lineages, which emerged almost simultaneously from different parts of Africa (reviewed in [30]). The most extensive series of outbreaks was associated with the Indian Ocean lineage (IOL), which first emerged in 2004 in coastal Kenya [25] and subsequently spread to several Indian Ocean islands (Comoros, Mayotte, Seychelles, Reunion, Madagascar, Sri Lanka and the Maldives), India, Southeast Asia (Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand) and China. In addition, IOL strains for the first time emerged in Europe, causing autochthonous transmission in Italy (2007) and France (2010) [31,32]. The second waive of outbreaks, which resulted in 20,000 human cases, began in 2006 in Cameroon and spread to Gabon in 2007. These etiologic strains also belong to the ECSA genotype, but in contrast to the IOL they are directly related to strains of 1999–2000 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The third CHIKV lineage, associated with a 2006 outbreak in Malaysia, belongs to the endemic Asian genotype (see [13,30] and PromedMail.org for details). Interestingly, since 2006, no strains of this endemic Asian genotype have been associated with epidemic activity, suggesting that the introduction and establishment of the IOL in Southeast Asia may have resulted in the competitive displacement of the older Asian genotype [30].

b. Genetics of vector susceptibility and host range changes

Factors that probably facilitated recent CHIKV emergences include: 1) the availability of immunologically naïve human populations in vast geographic areas; 2) CHIKV reliance on peridomestic and anthropophilic mosquitoes as vectors; 3) increase in international travel, and; 4) genetic adaptation of CHIKV to a new mosquito vector, A. albopictus [33]. Although originally native only to Asia, this mosquito has greatly expanded its geographic range in recent years, and currently occurs in Africa, the Americas, the Middle East and Europe [34,35]. Although A. albopictus is known to be susceptible to CHIKV, until 2006 there was no direct evidence to support its role in epidemic transmission. However, beginning in 2006, A. albopictus was repeatedly incriminated as the principal vector during several outbreaks in the Indian Ocean, parts of India, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Sri-Lanka, Gabon and Italy (reviewed in [30]). CHIKV transmission by A. albopictus was consistently associated with an amino acid substitution in the E1 protein (E1-A226V), which was selected convergently by CHIKV strains on at least 4 separate occasions (Fig. 3)[36–38]. Laboratory investigations confirmed that this mutation is directly responsible for a significant increase (50–100-fold) in infectivity, dissemination and transmission by A. albopictus [36,39]. Interestingly, several positions in the CHIKV genome were later discovered to exert strong epistatic effects on the E1-A226V substitution (Fig. 4)[30,40]. These epistatic interactions are lineage-specific, and block the ability of most ECSA strains (E2-211I) and all endemic Asian strains (E1-98T) to adapt to A. albopictus via the E1-A226V substitution. In contrast, IOL strains, which have E-211T and E1-98A residues, are not affected by these interactions, explaining their adaptability and epidemiologic success. Moreover, another new substitution, E2-L210Q, was recently discovered in strains of IOL isolated in Kerala state of India [41], and subsequent laboratory studies demonstrated that it provides an additional selective advantage for CHIKV transmission by A. albopictus (KAT, SCW, unpublished). Thus, the IOL lineage of CHIKV continues to evolve and adapt for more efficient transmission by A. albopictus with the risk of more severe and extensive epidemics.

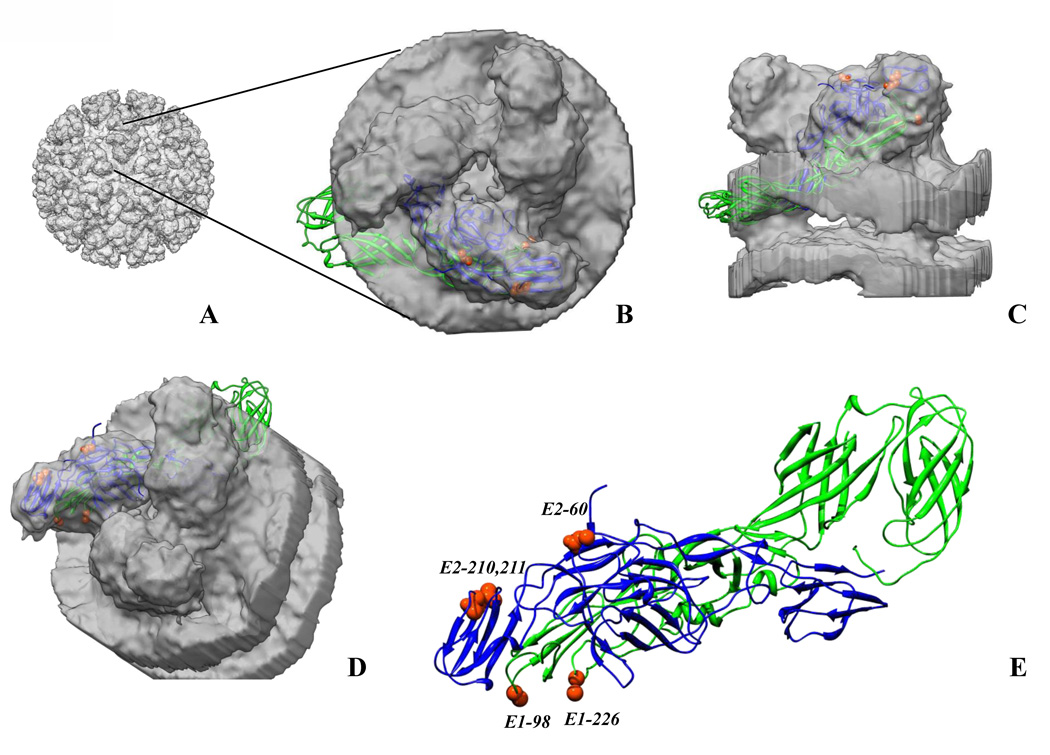

Fig. 4.

Chikungunya E1–E2 heterodimer (pdb ID 3N44, chains B and F, [4]) fitted into cryo-electron microscopy map of the alphavirus, western equine encephilitis virus (WEEV; a chikungunya map is not available) [54]. A. 3D WEEV cryoEM map showing E1–E2 spikes on the surface of the virus. B. Top view of a spike from the map with an E1–E2 heterodimer fitted into the density. Part of E1 is projecting out from the density owing to the restricted size of the spike density cut out from the WEEV map. C. Side view of the spike with an E1–E2 heterodimer within the density. D. The spike rotated to show the amino acid residues in the E1–E2 structure involved in the mosquito host range. E. E1–E2 structure [4] in the same orientation as in D. with amino acid residues involved in the mosquito host range labeled (shown as orange red spheres). The Figure was prepared using Chimera.

Amino acids E2–210 and E-211 are located in domain B of the E2 protein [4], which probably interacts with cell receptors. Position E1–98 is located in the base of the fusion loop and presumably modulate the kinetics of the pH-dependent conformational changes and fusion reaction in a particular endosomal compartment of A. albopictus midgut epithelial cells [30]. Substitution E2-D60G also modulates CHIKV infectivity for both A. albopictus and A. aegypti, but was probably the result of CHIKV adaptation to cell culture replication, and thus does not play a role in emergence [40] (Fig. 4).

IV. Future prospects

a. Potential for CHIK emergence in the Americas (150)

Experience with dengue virus, which is transmitted in its epidemic cycle in a manner indistinguishable from that of CHIKV, suggests that both South and North America are at risk for CHIK epidemics and permanent endemicity. The main CHIKV vectors, A. albopictus and A. aegypti, are present on both continents [34] and almost completely naive American human populations would enable rapid spread of the virus. Also, CHIKV could potentially establish an enzootic cycle in the Americas like yellow fever virus did when it was introduced several hundred years ago from Africa [42]. The potential of CHIKV to invade new geographic ranges, including temperate areas of industrialized nations, was underscored by the Italian and French outbreaks of 2007 and 2010, respectively, which were initiated by viremic travelers returning from CHIK-endemic regions [31,32,43]. In the Americas between 1995 and 2009, 109 imported CHIK cases were identified in the U.S. alone, and among those 13 (12%) exhibited viremia [44]. Also, CHIKV was detected in travelers returning to Canada, Brazil and Guyana (see PromedMail.org), the latter 2 countries hyperendemic for dengue. Moreover, dengue virus recently re-emerged in the U.S., emphasizing the challenge of controlling peridomestic arbovirus circulation, even in resource-rich nations. All of this information suggests that the establishment of CHIKV in endemic American transmission cycles may be inevitable unless circulation can be controlled in Africa and Asia.

b. Prospects for prevention and control of CHIK (200)

Currently the only method to control CHIK is to reduce the exposure of people to infection by mosquito vectors. In the African enzootic cycles, vector control in or near forest habitats is challenging due to their remote and extensive nature. The control of endemic/epidemic transmission is potentially more feasible, but experience with dengue indicates that A. aegypti control has rarely been achieved, even in resource-rich nations. But the less endophilic nature of A. albopictus makes it more susceptible to outdoor adulticide spray applications.

There is no therapeutic available to inhibit CHIKV replication during human infection to reduce viremia or expedite recovery. Anti-inflammatory drugs are used to treat the highly debilitating arthralgia. Ideally, the control of CHIK could be achieved by the use of an effective vaccine, and several are under development. These include inactivated, whole-virus [45], DNA [46], virus-like particles [47], and adenovirus-vectored formulations [48]. Although these non-replicating vaccines offer a high degree of safety, none induces rapid or long-lived immunity after a single dose, and some may be expensive to produce. Therefore, an ideal vaccine for resource-poor endemic locations would be a live-attenuated product. The first such described, strain 181/clone25, was reactogenic in clinical trials [49]. More recently, chimeric alphaviruses that combine the genetic backbone of attenuated strains with a wild-type CHIKV structural polyprotein ORF have shown promise in preclinical trials [50,51]. A novel attenuation approach that also prevents infection of mosquitoes, utilizing a picornavirus internal ribosome entry sequence, was recently described and shows great promise for CHIK prevention [52].

Tsetsarkin et al. highlights.

Chikungunya is a mosquito-borne, zoonotic virus of nonhuman primates in Africa, but most human disease occurs following emergence into an urban human-mosquito cycle.

Emergence from Africa into India and Southeast Asia occurred between 1920–1950 and again in 2005, resulting in major epidemics involving millions of persons.

The 2005 emergence was facilitated by an A226V substitution in the E1 envelope glycoprotein, which increased infectivity for a new vector, Aedes albopictus, by ca. 100-fold.

Several enzootic African lineages as well as the endemic Asian lineage circulating since the 1950s exhibit no penetrance of the A226V substitution due to epistatic interactions of other glycoprotein residues.

These findings underscore the complex genetic interactions that can have major impacts on RNA viral diseases and the difficulty of predicting emergence without a more complete understanding of viral-host interactions at a molecular level.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ research on chikungunya virus is supported by NIH grants AI082202 and AI069145. KAT was supported by the James W. McLaughlin Fellowship Fund,

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weaver SC, Frey TK, Huang HV, Kinney RM, Rice CM, Roehrig JT, Shope RE, Strauss EG. Togaviridae. In: Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, editors. Virus Taxonomy, VIIIth Report of the ICTV. Elsevier/Academic Press; 2005. pp. 999–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DW, Mackenzie JS, Weaver SC. Alphaviruses. In: Richman DD, Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, editors. Clinical Virology. ASM Press; 2009. pp. 1241–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fros JJ, Liu WJ, Prow NA, Geertsema C, Ligtenberg M, Vanlandingham DL, Schnettler E, Vlak JM, Suhrbier A, Khromykh AA, et al. Chikungunya virus nonstructural protein 2 inhibits type I/II interferon-stimulated JAK-STAT signaling. J Virol. 2010;84:10877–10887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00949-10.. Using infectious viruses and replicon virus-like particles, the authors demonstrated that CHIKV nsP2 is responsible for inhibition of interferon types I and II-induced signaling pathways. This finding suggests that modulation of innate host immunity could play an important role in CHIKV pathogenesis

- 4. Voss JE, Vaney MC, Duquerroy S, Vonrhein C, Girard-Blanc C, Crublet E, Thompson A, Bricogne G, Rey FA. Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature. 2010;468:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09555.. Using X-ray crystallography, the authors solved for the first time the atomic stricture of the complete E3-E2-E1 glycoprotein complex of an alphavirus. This information provides a structural basis for explaining many biological properties of alphaviruses.

- 5.Kielian M. Class II virus membrane fusion proteins. Virology. 2006;344:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnamoorthy K, Harichandrakumar KT, Krishna Kumari A, Das LK. Burden of chikungunya in India: estimates of disability adjusted life years (DALY) lost in 2006 epidemic. J Vector Borne Dis. 2009;46:26–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerardin P, Fianu A, Malvy D, Mussard C, Boussaid K, Rollot O, Michault A, Gauzere BA, Breart G, Favier F. Perceived morbidity and community burden after a Chikungunya outbreak: the TELECHIK survey, a population-based cohort study. BMC Med. 9:5. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavalankar D, Shastri P, Bandyopadhyay T, Parmar J, Ramani KV. Increased mortality rate associated with chikungunya epidemic, ahmedabad, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:412–415. doi: 10.3201/eid1403.070720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casolari S, Briganti E, Zanotti M, Zauli T, Nicoletti L, Magurano F, Fortuna C, Fiorentini C, Grazia Ciufolini M, Rezza G. A fatal case of encephalitis associated with Chikungunya virus infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:995–996. doi: 10.1080/00365540802419055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganesan K, Diwan A, Shankar SK, Desai SB, Sainani GS, Katrak SM. Chikungunya encephalomyeloradiculitis: report of 2 cases with neuroimaging and 1 case with autopsy findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1636–1637. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Josseran L, Paquet C, Zehgnoun A, Caillere N, Le Tertre A, Solet JL, Ledrans M. Chikungunya disease outbreak, Reunion Island. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1994–1995. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tandale BV, Sathe PS, Arankalle VA, Wadia RS, Kulkarni R, Shah SV, Shah SK, Sheth JK, Sudeep AB, Tripathy AS, et al. Systemic involvements and fatalities during Chikungunya epidemic in India, 2006. J Clin Virol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powers AM, Logue CH. Changing patterns of chikungunya virus: re-emergence of a zoonotic arbovirus. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:2363–2377. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diallo M, Thonnon J, Traore-Lamizana M, Fontenille D. Vectors of chikungunya virus in Senegal: current data and transmission cycles. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999;60:281–286. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jupp PG, McIntosh BM. Chikungunya virus disease. In: Monath TP, editor. The Arbovirus: Epidemiology and Ecology. Vol. II. CRC Press; 1988. pp. 137–157. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chevillon C, Briant L, Renaud F, Devaux C. The Chikungunya threat: an ecological and evolutionary perspective. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apandi Y, Nazni WA, Noor Azleen ZA, Vythilingam I, Noorazian M, Azahari AH, Zainah S, Lee HL. The first isolation of chikungunya virus from nonhuman primates in Malaysia. J Gen Mol Virol. 2009;1:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carey DE. Chikungunya and dengue: a case of mistaken identity? J. Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 1971;26:243–262. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/xxvi.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Peyrefitte CN, Yogolelo R, Mathina Basisya E, Koyange D, Pukuta E, Mashako M, Tolou H, Durand JP. Epidemic of Chikungunya virus in 1999 and 200 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Med Trop (Mars) 2003;63:637–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laras K, Sukri NC, Larasati RP, Bangs MJ, Kosim R, Djauzi, Wandra T, Master J, Kosasih H, Hartati S, et al. Tracking the re-emergence of epidemic chikungunya virus in Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers AM, Brault AC, Tesh RB, Weaver SC. Re-emergence of Chikungunya and O'nyong-nyong viruses: evidence for distinct geographical lineages and distant evolutionary relationships. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:471–479. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney MC, Lavenir R, Pardigon N, Reynes JM, Pettinelli F, et al. Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arankalle VA, Shrivastava S, Cherian S, Gunjikar RS, Walimbe AM, Jadhav SM, Sudeep AB, Mishra AC. Genetic divergence of Chikungunya viruses in India (1963–2006) with special reference to the 2005–2006 explosive epidemic. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:1967–1976. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherian SS, Walimbe AM, Jadhav SM, Gandhe SS, Hundekar SL, Mishra AC, Arankalle VA. Evolutionary rates and timescale comparison of Chikungunya viruses inferred from the whole genome/E1 gene with special reference to the 2005–07 outbreak in the Indian subcontinent. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kariuki Njenga M, Nderitu L, Ledermann JP, Ndirangu A, Logue CH, Kelly CH, Sang R, Sergon K, Breiman R, Powers AM. Tracking epidemic Chikungunya virus into the Indian Ocean from East Africa. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2754–2760. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/005413-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sam IC, Chan YF, Chan SY, Loong SK, Chin HK, Hooi PS, Ganeswrie R, Abubakar S. Chikungunya virus of Asian and Central/East African genotypes in Malaysia. J Clin Virol. 2009;46:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng LC, Tan LK, Tan CH, Tan SS, Hapuarachchi HC, Pok KY, Lai YL, Lam-Phua SG, Bucht G, Lin RT, et al. Entomologic and virologic investigation of Chikungunya, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1243–1249. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Volk SM, Chen R, Tsetsarkin KA, Adams AP, Garcia TI, Sall AA, Nasar F, Schuh AJ, Holmes EC, Higgs S, et al. Genome-scale phylogenetic analyses of chikungunya virus reveal independent emergences of recent epidemics and various evolutionary rates. J Virol. 2010;84:6497–6504. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01603-09.. This study, which represents the most comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of CHIKV sequences to date, determined that CHIKV emerged independently from East Africa into the Indian Ocean and Asia in 2004–2006, and suggested fundamental differences in evolution of CHIKV in urban versus enzootic transmission cycles.

- 29.Schwartz O, Albert ML. Biology and pathogenesis of chikungunya virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:491–500. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsetsarkin KA, Chen R, Leal G, Forrester N, Higgs S, Huang J, Weaver SC. Chikungunya virus emergence is constrained in Asia by lineage-specific adaptive landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7872–7877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018344108.. Using a reverse genetic approach, the authors demonstrated that CHIKV strains of the endemic Asian genotype have been for at least 6 decades restricted in their ability to adapt to the mosquito vector, Aedes albopictus. This explained the epidemiological success of recently introduced A. albopictus-adapted African CHIKV strains in southeast Asia.

- 31.Rezza G, Nicoletti L, Angelini R, Romi R, Finarelli AC, Panning M, Cordioli P, Fortuna C, Boros S, Magurano F, et al. Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: an outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet. 2007;370:1840–1846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grandadam M, Caro V, Plumet S, Thiberge JM, Souares Y, Failloux AB, Tolou HJ, Budelot M, Cosserat D, Leparc-Goffart I, et al. Chikungunya virus, southeastern France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:910–913. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weaver SC, Reisen WK. Present and future arboviral threats. Antiviral Res. 2009;85:328–345. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gratz NG. Critical review of the vector status of Aedes albopictus. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:215–227. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benedict MQ, Levine RS, Hawley WA, Lounibos LP. Spread of the tiger: global risk of invasion by the mosquito Aedes albopictus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:76–85. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.0562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hapuarachchi HC, Bandara KB, Sumanadasa SD, Hapugoda MD, Lai YL, Lee KS, Tan LK, Lin RT, Ng LF, Bucht G, et al. Re-emergence of Chikungunya virus in South-east Asia: virological evidence from Sri Lanka and Singapore. J Gen Virol. 2009;91:1067–1076. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015743-0.. This study provided a detailed phylogenetic description of the emergence and evolution of recently emerged African strains of CHIKV in Southeast Asia. In particular, the study emphasized the role of Aedes albopictus-adaptive mutation, the E1-A226V, in the dramatic spread of CHIKV in this region.

- 38.de Lamballerie X, Leroy E, Charrel RN, Ttsetsarkin K, Higgs S, Gould EA. Chikungunya virus adapts to tiger mosquito via evolutionary convergence: a sign of things to come? Virol J. 2008;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vazeille M, Moutailler S, Coudrier D, Rousseaux C, Khun H, Huerre M, Thiria J, Dehecq JS, Fontenille D, Schuffenecker I, et al. Two Chikungunya isolates from the outbreak of La Reunion (Indian Ocean) exhibit different patterns of infection in the mosquito, Aedes albopictus. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsetsarkin KA, McGee CE, Volk SM, Vanlandingham DL, Weaver SC, Higgs S. Epistatic roles of E2 glycoprotein mutations in adaption of chikungunya virus to aedes albopictus and ae. Aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niyas KP, Abraham R, Unnikrishnan RN, Mathew T, Nair S, Manakkadan A, Issac A, Sreekumar E. Molecular characterization of Chikungunya virus isolates from clinical samples and adult Aedes albopictus mosquitoes emerged from larvae from Kerala, South India. Virol J. 2010;7:189. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryant JE, Holmes EC, Barrett AD. Out of Africa: a molecular perspective on the introduction of yellow fever virus into the Americas. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e75. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angelini R, Finarelli AC, Angelini P, Po C, Petropulacos K, Silvi G, Macini P, Fortuna C, Venturi G, Magurano F, et al. Chikungunya in north-eastern Italy: a summing up of the outbreak. Euro Surveill. 2007;12:E071122–E071122. doi: 10.2807/esw.12.47.03313-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gibney KB, Fischer M, Prince HE, Kramer LD, St George K, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, Staples JE. Chikungunya fever in the United States: a fifteen year review of cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e121–e126. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq214.. This study provides a summary of CHIKV infections detected in travelers returning to the U.S., and emphasizes the risk of establishment of a local CHIKV transmission cycle in there or elsewhere in the western hemisphere.

- 45.Tiwari M, Parida M, Santhosh SR, Khan M, Dash PK, Rao PV. Assessment of immunogenic potential of Vero adapted formalin inactivated vaccine derived from novel ECSA genotype of Chikungunya virus. Vaccine. 2009;27:2513–2522. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mallilankaraman K, Shedlock DJ, Bao H, Kawalekar OU, Fagone P, Ramanathan AA, Ferraro B, Stabenow J, Vijayachari P, Sundaram SG, et al. A DNA vaccine against chikungunya virus is protective in mice and induces neutralizing antibodies in mice and nonhuman primates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Akahata W, Yang ZY, Andersen H, Sun S, Holdaway HA, Kong WP, Lewis MG, Higgs S, Rossmann MG, Rao S, et al. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med. 16:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nm.2105.. This study described the development and evaluation of a novel CHIK vaccine candidate constructed based on pseudo-typed lentiviral vectors. Tests in monkey demonstrated that the vaccine induces a strong neutralizing antibody response that protected against CHIKV challenge.

- 48.Wang D, Suhrbier A, Penn-Nicholson A, Woraratanadharm J, Gardner J, Luo M, Le TT, Anraku I, Sakalian M, Einfeld D, et al. A complex adenovirus vaccine against chikungunya virus provides complete protection against viraemia and arthritis. Vaccine. 2011;29:2803–2809. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edelman R, Tacket CO, Wasserman SS, Bodison SA, Perry JG, Mangiafico JA. Phase II safety and immunogenicity study of live chikungunya virus vaccine TSI-GSD-218. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:681–685. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang E, Volkova E, Adams AP, Forrester N, Xiao SY, Frolov I, Weaver SC. Chimeric alphavirus vaccine candidates for chikungunya. Vaccine. 2008;26:5030–5039. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim DY, Atasheva S, Foy NJ, Wang E, Frolova EI, Weaver S, Frolov I. Design of chimeric alphaviruses with a programmed, attenuated, cell type-restricted phenotype. J Virol. 2011;85:4363–4376. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00065-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Plante KS, Wang E, Partidos CD, Weger J, Gorchakov R, Tsetsarkin KA, Borland EM, Powers AM, Seymour R, Stinchcomb DT, et al. Novel chikungunya vaccine candidate with an IRES-based attenuation and host range alteration mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002142. in press.. This paper describes an alternative approach to CHIK vaccine development that relies on the substitution of the CHIKV sub-genomic promoter with a picornavirus internal ribosome entry site. The authors demonstrated that this vaccine strain is restricted in ability to replicate in mosquitoes, and is highly immunogenic and efficacious in protecting mice after a single dose. This and vaccine described above (Akahata et al) offer promise to control and prevent future CHIK epidemics.

- 53.Soumahoro MK, Gerardin P, Boelle PY, Perrau J, Fianu A, Pouchot J, Malvy D, Flahault A, Favier F, Hanslik T. Impact of Chikungunya virus infection on health status and quality of life: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherman MB, Weaver SC. Structure of the recombinant alphavirus Western equine encephalitis virus revealed by cryoelectron microscopy. J Virol. 2010;84:9775–9782. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00876-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]