Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We describe our experience with oncology patients on a frequent dosing schedule of intravenous (i.v.) bisphosphonates at the Jordan University Hospital (JUH).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients treated by i.v. bisphosphonates in the medical oncology unit at the JUH were examined for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ). Diagnosis was made according to the guidelines of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) original position paper.

RESULTS

Of the 41 patients, four developed BRONJ, two in maxilla, one in mandible and one bimaxillary. Patients with BRONJ were older; mean age was 69.3 ±3.1 years compared to 62.8 ± 12.5 years (P = 0.022). Dental co-morbidities were more commonly present in patients with the disease (P = 0.038). Patients who developed BRONJ were on treatment for a longer duration of time; the mean duration of treatment was 23.5 ± 8.4 months compared to 11.9 ± 13.4 months (P = 0.10).

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this case series demonstrated that age and poor oral health status are significant risk factors of BRONJ for oncology patients on long-term frequent dosing schedule of i.v. bisphosphonates.

Keywords: Bisphosphonates, Osteonecrosis of jaw, Chemotherapy

Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ), first described by Marx,1 is defined as jaw necrosis occurring either spontaneously or, more commonly, after simple dento-alveolar surgery in patients on bisphosphonates, commonly with the intravenous (i.v.) form of the drug.2 Bisphosphonates are non-metabolised analogues of pyrophosphate that localise to bone inhibiting the dissolution of hydroxyapatite crystals preventing bone resorption.2,3 Other effects include reducing blood flow and anti-angiogenic properties,4 contributing to the ischaemic changes noted in the affected jawbones. Bisphosphonates are preferentially deposited in bones with high turn-over rates, since the maxilla and mandible are sites of significant remodelling, it is possible that the levels of the drug within the jaw are selectively elevated.2 BRONJ is a multifactorial event with multicellular impairments, resulting in altered wound healing.5

Cancer patients with metastatic or primary bone lesions often develop sequential skeletal complications and hyper-calcaemia of malignancy.6 Intravenous bisphosphonates are primarily used in the management of cancer-related hyper-calcaemia and skeletal-related events associated with bone metastases including pain, pathological fracture, spinal cord compression, mostly with solid tumours such as breast, prostate and lung cancers.6 They are also effective in the management of lytic lesions in the setting of multiple myeloma;7 multiple myeloma patients appear to have a uniquely elevated risk for the development of the condition as the disease itself is present in bone.8 The most prevalent and common indication for oral bisphosphonates is osteoporosis.9

Pamidronate (Aredia; Novartis) and the newer more potent zoledronate (Zometa; Novartis) are bisphosphonates approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA);10 both drugs are administered intravenously. More recently, a once-yearly formulation of zoledronate (Reclast; Novartis) has been approved by the FDA. Only in 2004 did the manufacturer of the drugs notify healthcare professionals of the risk of developing BRONJ.11 The aim of this study was to look at the prevalence of BRONJ in oncology patients on a frequent dosing schedule of i.v. bisphosphonates at the Jordan University Hospital (JUH) and to identify potential risk factors.

Patients and Methods

Patients who were receiving i.v. bisphosphonates in medical oncology at JUH were invited to participate in this observational study. They were subjected to a thorough clinical and radiographic oral examination in the oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) unit; they were reviewed each time they were scheduled for an i.v. bisphosphonate dose. Medical notes were reviewed to exclude the presence of jaw osteonecrosis prior to bisphosphonate treatment. Approval for the study was obtained from the local research committee and data collection commenced in December 2007. Informed consent was obtained from patients; clinical examination was carried out by two authors (ZB and ZT). Data on gender, age, primary diagnosis, medical and dental co-morbidities, bisphosphonates used and duration of treatment were collected. The diagnosis of BRONJ was made according to the guidelines reported by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) original position paper on BRONJ when the following were present: current or previous treatment with bisphosphonates, exposed necrotic bone in the jaws that has persisted for more than 8 weeks and no history of radiation therapy to the jaws.12 In cases of osteonecrosis, site, manifestations, management, postoperative course and overall outcome were noted.

Treatment was conducted according to the staging system introduced by Ruggiero et al.:2

Stage 1 Exposed and necrotic bone in asymptomatic patients with no clinical evidence of infection, only antibacterial mouth rinses with oral hygiene measures and patient education about the risks of developing BRONJ.

Stage 2 In the presence of local infection in the area of bony exposure, treatment with antibacterial mouth rinse, pain control, superficial debridement to relieve soft tissue irritation, antibiotic therapy.

Stage 3 In the presence of pathological fracture, extra-oral fistula or extensive osteolysis, all previous measures were used along with surgical debridement and/or resection, in addition, long-term oral or/and i.v. antibiotics were used.3

The antibiotic protocol used included co-amoxiclac and metronidazole in combination; they were introduced during and after surgery until the mucosal erythema and swelling had resolved. Bisphosphonate therapy was stopped before the planned surgical intervention in liaison with the treating physicians.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows v16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Frequency distributions were obtained and chi-squared test and t-test were used to compare differences between groups. Fisher's Exact test was used when the expected numbers of patients within subgroups were small. Differences at the 5% level were accepted as significant.

Results

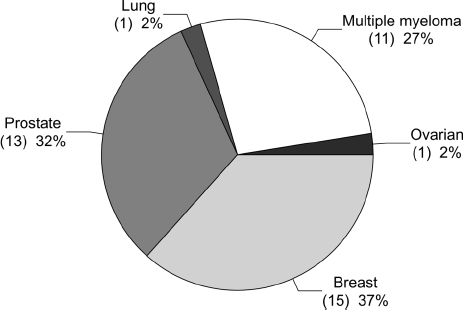

This study group included 41 patients ranging in age from 29–88 years (mean, 63.4 years), there were 16 men (39%) and 25 women (61%). The distribution of disease is shown in Figure 1; most (39 patients; 95%) were treated with Zoledronate, one (2.5%) with zoledronate and alendronate and one (2.5%) with Pamidronate (further details of all patients are shown in Table 1). Patients were on a frequent dosing schedule 8–12 times annually. According to clinical notes, patients had no clinical or radiographic signs of osteonecrosis at the start of treatment. The duration of treatment with bisphosphonate ranged between 1–48 months (median, 6.5 months); the majority (31 patients; 76%) had associated medical morbidities.

Figure 1.

Distribution of disease.

Table 1.

Summary of patients included in the study

| Patient no. | Age (yrs) | Sex | Disease | Bisphosphonate | Duration of treatment (months) | Co-morbidities | Clinical presentation | Dental co-morbidities | Radiography | Management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | F | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 20 | Chemotherapy, steroids | Symptomatic exposed bone in anterior mandible and posterior maxilla, indurated submental orocutaneous fistula (Stage 3) | Ill-fitting dentures | Osteolysis | Stopped zoledronate; surgical incision and drainage; surgical debridement of exposed bone; antibiotic treatment; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash; replacing old denture | Asymptomatic bony exposure in the mandible |

| 2 | 73 | M | Multiple myeloma | Pamidronate | 2 | Steroids | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 | 63 | M | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 5 | Chemotherapy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 | 29 | F | Lung cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 48 | Chemotherapy, steroids | – | Poor oral hygiene | – | Deceased | |

| 5 | 75 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 7 | Chemotherapy, steroids | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6 | 69 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 20 | Chemotherapy, steroids | Symptomatic exposed lingual aspect of body/ramus in the right mandible (Stage 2) | Periodontally involved lower right second molar | Osteolysis | Stopped zoledronate; surgical debridement of exposed bone; extraction of the lower right second molar; antibiotic treatment; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash | Asymptomatic bony exposure in the mandible |

| 7 | 58 | F | Multiple myeloma and osteoporosis | Zoledronate and alendronate | 28 | Chemotherapy, steroids | – | Poor oral hygiene, multiple carious teeth and mandibular tori | – | – | – |

| 8 | 72 | F | Breast cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 14 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9 | 55 | F | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 24 | Chemotherapy, steroids | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 45 | F | Breast cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11 | 45 | F | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 5 | Steroids | – | – | – | – | – |

| 12 | 77 | M | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 6 | Steroids | – | – | – | – | – |

| 13 | 50 | F | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 4 | Steroids | – | Dental abscess | – | – | – |

| 14 | 46 | F | Brest cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 3 | Chemotherapy, steroids | – | Localised periodontal disease | – | – | – |

| 15 | 67 | F | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 6 | Steroids | – | Localised periodontal disease | – | – | – |

| 16 | 45 | F | Breast cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 8 | Chemotherapy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 17 | 55 | F | Breast cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 8 | Chemotherapy, steroids | – | Generalised recession | – | – | – |

| 18 | 66 | F | Breast cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 19 | 66 | F | Breast cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 18 | Chemotherapy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 20 | 72 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 36 | Chemotherapy, radiotherap | Small asymptomatic area of exposed bone at the site of impacted third molar in the maxilla (Stage 1) | Pericoronitis and periodontal disease | Osteosclerosis | Periodontal treatment; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash; antibiotic treatment | No change |

| 21 | 88 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 2 | Chemotherapy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 22 | 77 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 36 | Chemotherapy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 23 | 75 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 12 | Chemotherapy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 24 | 61 | F | Ovarian cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 3 | Chemotherapy, steroids | – | – | – | – | – |

| 25 | 50 | F | Breast cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 4 | Chemotherapy | – | Gingivitis | – | Periodontal treatment; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash | – |

| 26 | 82 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 2 | – | – | Periodontitis, multiple carious teeth | – | Antibiotics; periodontal treatment; dental extractions; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash | – |

| 27 | 62 | F | Breast cancer | Zoledronate | 8 | Chemotherapy | – | Chronic dental infection | – | Antibiotics; dental extractions; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash | – |

| 28 | 60 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 6 | – | – | Ill-fitting dentures | – | Construction of new dentures | – |

| 29 | 73 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 1 | – | – | Multiple carious teeth | – | Periodontal treatment; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash | – |

| 30 | 74 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 48 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 31 | 75 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 32 | 66 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 5 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 33 | 67 | F | Breast cancer | Zoledronate | 48 | – | – | Gingivitis | – | Periodontal treatment; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash | – |

| 34 | 56 | F | Breast cancer | Zoledronate | 24 | Renal failure | – | Gingivitis | – | Periodontal treatment; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash | – |

| 35 | 69 | F | Breast cancer | Zoledronate | 2 | Radiotherapy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 36 | 57 | F | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 2 | Diabetes mellitus | – | Gingivitis | – | Periodontal treatment; oral hygiene practices; mouth wash | – |

| 37 | 68 | F | Breast cancer | Zoledronate | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 38 | 47 | F | Breast cancer | Zoledronate | 11 | – | – | Gingivitis and carious teeth | – | – | – |

| 39 | 71 | F | Multiple myeloma | Zoledronate | 18 | Chemotherapy, steroids | Symptomatic exposed bone in the premolar region of the right maxilla (Stage 2) | Ill-fitting dentures | – | Stopped zoledronate; surgical debridement of exposed bone; antibiotic treatment; mouth wash; replacing old denture | Asymptomatic bony exposure |

| – | |||||||||||

| 40 | 68 | M | Prostate cancer with bone metastasis | Zoledronate | 5 | Chemotherapy, steroids | – | – | – | – | – |

| 41 | 60 | FM | Breast cancer | Zoledronate | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

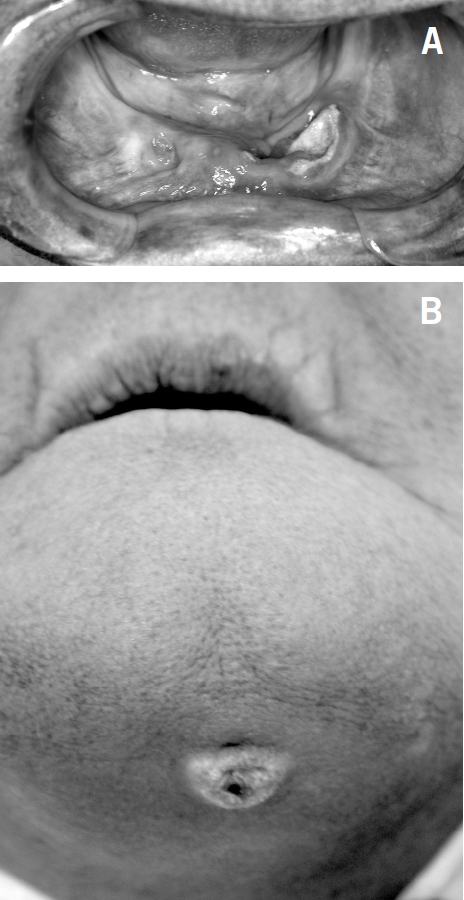

Of the 41 patients who received bisphosphonates, four (9.7%) had BRONJ; two in maxilla, one in mandible and one in maxilla and mandible (Figs 2 and 3). Osteonecrosis was symptomatic in three cases and asymptomatic in one case. Two of the four cases occurred in males with prostate cancer and two in females with multiple myeloma: all were only treated by Zoledronate, all had associated morbidities; two were receiving chemotherapy plus steroids, one chemotherapy and radiotherapy and one chemotherapy, steroids and smoking. The affected patients had dental co-morbidities; two had ill-fitting dentures and two had peri-odontitis (one of the latter also suffered pericoronitis). Patients with BRONJ were older; mean age was 69.3 ± 3.1 years (range, 65–72 years) compared to 62.8 ± 12.5 years for those who did not have osteonecrosis (P = 0.022). The duration of treatment with bisphosphonate was longer (23.5 ± 8.4 months) in patients who had BRONJ compared with those who did not (11.9 ± 13.4 months); however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.10).

Figure 2.

Patient number 1. (A) Exposed necrotic bone in the anterior mandible; (B) orocutaneous fistula.

Figure 3.

Patient number 6. Computed tomograph showing osteolysis of the lingual plate of the mandible.

Surgical debridement was performed for three patients (patients 1, 6 and 39) to include removal of the exposed necrotic bone and sequestra. Closure with an mucosal advancement flap was performed for patient number 1. Extraction of involved or questionable adjacent teeth, along with saucerisation and smoothing of the bone, was carried for patient number 6.

Oral antibiotics were prescribed; however, in patient number 1, secondary osteomyelitis was suspected and she was given antibiotics intravenously for 4 weeks postoperatively. Hyperbaric oxygen was not pursued.

Discussion

The frequency estimates for BRONJ in patients exposed to oral bisphosphonate is low; however, with i.v. bisphosphonates, it has been reported to be between 1–12%.3,12,13 The results of this study (9.7%) fall within the reported range. Risk factors for BRONJ include: recent dento-alveolar surgery,2,14,15 bisphosphonate exposure and frequency of administration,16,17 potency of the drug,16,18 local anatomy (mandible more common than maxilla and more common in areas with thin oral mucosa like tori and mylohyoid ridge),12 oral disease, systemic conditions and co-morbidities,12,18 and finally genetic factors.19 All four cases of confirmed BRONJ in this study had dental co-morbidities as inciting event. Positive cases were undergoing chemotherapy; views on chemotherapy as a risk factor in the literature are varied.15 Patients who had the disease received the drug for a longer duration compared to patients who were disease free; this conforms with a previous finding on the importance of the duration of i.v. bisphosphonate exposure.16 However, the difference did not reach statistical significance. Age as a significant risk factor was demonstrated in this report (69.3 vs 62.9 years; P < 0.05) as expressed in the updated AAOMS taskforce position paper on BRONJ.15 Two of the four cases had bone metastasis; however, there is no evidence in the literature to suggest a significant association.

Unlike osteoradionecrosis, this disease affects the entire jaw bone; hence, significant morbidity maybe a sequela and prevention becomes an essential part of patient care.15 Prior to treatment with i.v. bisphosphonates, any unsalvageable teeth should be removed, all invasive dental procedures should be completed and optimal periodontal health should be achieved.12 It is advisable to commence treatment after the socket has mucolised which could take up to 3 weeks or better when there is adequate osseous healing (at 4–6 weeks).2 Removable prostheses should be examined and any trauma induced by them should be removed; in this study, two edentulous patients developed the disease as a result of poorly fitting dentures. During i.v. bisphosphonate treatment for oncology patients, direct osseous injury to bone should be avoided, especially for those on a frequent dosing schedule;2,15 dento-alveolar trauma was not reported in any case in this study. Osteonecrosis of the jaw may remain asymptomatic for weeks, months or years, lesions are symptomatic when surrounding tissues become inflamed or there is clinical evidence of infection.

Conclusions

As an observational study, the data have inherent weakness. The limited number of patients and the retrospective collection of oral health status before commencing the bisphosphonate treatment sets limitations to inferences that can be drawn from the study. However, authors conclude that age and poor oral health status are significant risk factors for BRONJ and duration of treatment may be relevant. Therefore, in elderly patients on a long-term frequent dosing schedule, preventive oral health care before initiating i.v. bisphosphonates may have averted BRONJ.

References

- 1.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115–7. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggiero SL, Fantasia J, Carlson E. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: background and guidelines for diagnosis, staging and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:433–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutta R, Louis PJ. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws: science and rationale. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Beek ER, Löwik CW, Papapoulos SE. Bisphosphonates suppress bone resorption by a direct effect on early osteoclast precursors without affecting the osteoclastogenic capacity of osteogenic cells: the role of protein geranylgeranylation in the action of nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates on osteoclast precursors. Bone. 2002;30:64–70. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00655-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter C, Klein MO, Pabst A, Al-Nawas B, Duschner H, Ziebart T. Influence of bisphosphonates on endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and osteogenic cells. Clin Oral Invest. 2010;14:35–41. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodan GA, Fleisch HA. Bisphosphonates: mechanisms of action. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2692–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI118722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhry AN, Ruggiero SL. Osteonecrosis and bisphosphonates in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2007;19:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang EP, Kaban LB, Strewler GJ, Raje N, Troulis MJ. Incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma and breast or prostate cancer on intravenous bisphosphonate therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1328–31. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts NB. Bisphosphonate treatment of osteoporosis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19:395–414. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berenson JR, Hillner BE, Kyle RA, Anderson K, Lipton A, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Bisphosphonates Expert Panel. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guidelines: the role of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. The role of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3177–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohnecker JA. Novartis ‘Dear Doctor’ precautions added to label of Aredia and Zometa. 24 September 2004.

- 12.Advisory Task Force on Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws, American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:369–76. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLeod NM, Davies BJ, Brennan PA. Bisphosphonate osteonecrosis of the jaws; an increasing problem for the dental practitioner. Br Dent J. 2007;203:641–4. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Migliorati CA, Casiglia J, Epstein J, Siegel MA, Woo SB. Managing the care patients with bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis. JADA. 2005;136:1658–68. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, Landesberg R, Marx RE, Mehrotra B. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws – 2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(Suppl):2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durie BG, Katz M, Crowley J. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and bisphosphonates. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:99–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200507073530120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corso A, Varettoni M, Zappasodi P, Klersy C, Mangiacavalli S, et al. A different schedule of zoledronic acid can reduce the risk of the osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:1545–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wessel JH, Dodson TB, Zavras AI. Zoledronate, smoking, and obesity are strong risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaw: a case-control study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:625–31. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarasquete ME, Garcia-Sanz R, Marin L, Alcoceba M, Chillon MC, et al. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw is associated with polymorphisms of the cytochrome P450 CYP2C8 in multiple myeloma: a genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Blood. 2008;112:2709–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-147884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]