Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of oesophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma has increased rapidly over the previous two decades. There has been a rise in the number of younger patients affected, and the disease may be more aggressive and have a worse prognosis in these individuals. Current UK guidelines for urgent cancer referral focus on patients who are over 55 years. This study prospectively compares the referral times and outcome in a cohort of patients diagnosed with oesophagogastric cancer under the age of 55 years with a matched cohort over 55 of age.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Every patient diagnosed with oesophageal, junctional or gastric cancer under the age of 55 years and every subsequent patient over the age of 55 years was accepted into this study. In all, 17 hospitals participated over a 12-month period. The following data were recorded: duration of symptoms, number of fast-track referrals, duration from GP referral to first hospital visit and stage at presentation. A survival analysis between the two groups was conducted at 2 years after the end of recruitment.

RESULTS

In total, 102 patients under the age of 55 years were diagnosed with oesophagogastric cancer during the study period. There were fewer fast-track referrals from GPs in this group compared to the over 55-year matched cases (29.4% vs 40.2%). Duration of time from GP referral to first hospital visit was significantly longer in the under 55-year group (median 14 days vs 11 days; P = 0.045 Mann-Whitney). Stage at presentation was similar between groups, but a higher proportion of patients under 55 years were offered a curative treatment plan compared to those over 55 years (P < 0.01). Survival analysis conducted at 2 years after the end of recruitment demonstrated a longer median survival in the under 55-year group (348 days vs 248 days; P = 0.03 log rank).

CONCLUSIONS

Although there was a longer referral time in patients under the age of 55 years, this had no effect on disease stage at presentation. Patients under the age of 55 years diagnosed with oesophageal or gastric cancer appear to have a better prognosis than those aged over 55 years.

Keywords: Oesophageal cancer, Outcome, Survival

The incidence of oesophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma has increased rapidly in the UK over the previous two decades. Epidemiological evidence is emerging to suggest that patients are now being affected earlier in life13 and there is a perception amongst clinicians that these individuals are symptomatic for a longer duration before diagnosis and present with more advanced disease compared to older patients.2 In the published literature, however, there is little data to support these observations.

Current UK guidelines for suspected upper gastrointestinal cancer recommend urgent referral to endoscopy for patients with persistent and unexplained symptoms of dyspepsia but only in those over the age of 55 years.4 The guidelines suggest urgent referral for patients with certain alarm symptoms regardless of age, but these symptoms are likely to represent advanced disease. Accordingly, a number of patients under the age of 55 years with oesophagogastric cancer might be waiting longer to reach a diagnosis and consequently have a worse outcome. This study prospectively compares the referral times and outcome in a cohort of patients diagnosed with oesophagogastric cancer under the age of 55 years with a matched cohort over 55 years of age.

Patients and Methods

During a 12-month period from 1 September 2005 to 31 August 2006, every patient diagnosed with oesophageal, junctional or gastric cardia cancer under the age of 55 years at diagnosis, and every subsequent patient over the age of 55 years was accepted into this study. Seventeen hospital trusts over five cancer networks were asked to provide data.

Cases were identified and data collected by lead surgeons, specialist nurses and multidisciplinary team co-ordi-nators. The following data were recorded on an agreed pro-forma: duration of symptoms, number of fast-track referrals, duration from general practitioner (GP) referral to first hospital visit and stage at presentation.

Data were analysed with the help of a statistics package (Medcalc). The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare waiting times. A survival analysis between the two groups was conducted at 2 years after the end of recruitment using the log rank statistic.

Results

Participation

Seventeen hospital trusts participated in this study (Table 1). In total, 102 cases under the age of 55 years (range, 33–54 years) diagnosed with oesophagogastric cancer and 102 cases of 55 years and over (range, 55–87 years) were included in the study.

Table 1.

List of trusts participating in this study

| Cancer network | Trust | Number of cases under 55 years |

|---|---|---|

| Avon, Somerset, and Wiltshire | Bath | 3 |

| North Bristol | 8 | |

| Taunton | 2 | |

| Yeovil | 4 | |

| Weston | 7 | |

| University of Bristol | 8 | |

| Dorset | ||

| Bournemouth | 8 | |

| Poole | 1 | |

| Three counties | ||

| Gloucester | 17 | |

| Hereford | 4 | |

| Worcester | 8 | |

| Central South Coast | ||

| Salisbury | 2 | |

| Isle of Wight | 5 | |

| Southampton | 9 | |

| Chichester | 1 | |

| Peninsula | ||

| Exeter | 11 | |

| Truro | 4 | |

| Total | 102 | |

Symptoms

Duration of symptoms was similar in the two groups (median, 8 weeks). Symptoms at presentation were similar in the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Symptoms at presentation

| Symptoms | Cases under 55 years (n) | Cases of 55 years and over (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Dyspepsia | 43 | 32 |

| Chronic GI bleed | 4 | 5 |

| Dysphagia | 70 | 61 |

| Progressive unintentional weight loss | 55 | 51 |

| Vomiting | 19 | 13 |

| Iron-deficiency anaemia | 9 | 11 |

| Epigastric mass | 5 | 2 |

| Other | 32 | 25 |

Referral type and waiting times

There were fewer fast-track referrals from GPs in the under 55-year cohort compared to the over 55-year matched cases (29.4% vs 40.2%). Duration of time from GP referral to first hospital visit was significantly longer in the under 55-year group (median, 14 days vs 11 days; P = 0.045 Mann-Whitney; Table 3).

Table 3.

Waiting times

| Under 55 years/median days (highest) | 55 years and over/median days (highest) | |

|---|---|---|

| GP referral to first hospital visit | 14 (132) | 11 (147)* |

| GP referral to diagnosis | 14 (176) | 12 (147) |

| Diagnosis to MDT review | 10 (286) | 11 (90) |

| Diagnosis to initiation of treatment | 41 (161) | 41 (110) |

P = 0.045 for GP referral to first hospital visit comparison.

Stage at presentation

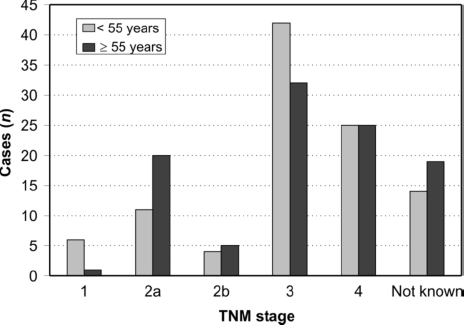

Stage at presentation was similar between both groups (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Stage at presentation.

Treatment plan

The treatment plans for the two groups are shown in Table 4. A greater proportion of patients under 55 years had a treatment plan of curative intent compared those 55 years and over (Fisher's exact test P < 0.01).

Table 4.

Treatment plans

| Under 55-year group (n = 102) | 55 and over (n = 102) | |

|---|---|---|

| Curative plan | 58 | 34* |

| Palliative plan | 44 | 68 |

| Resection | 49 | 24 |

| Chemo/radiotherapy alone | 42 | 43 |

P < 0.01 (Fisher's exact test).

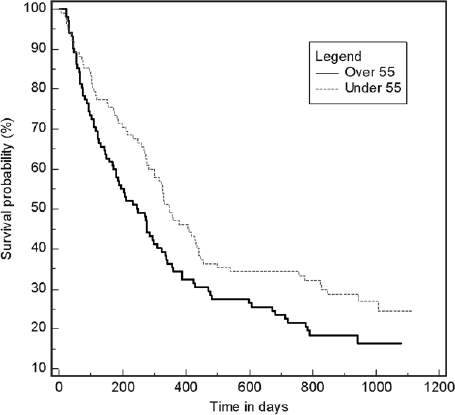

Two-year survival

Two-year survival analysis demonstrated that the under 55-year group had a longer median survival than the over 55-year group (348 days vs 248 days; P = 0.034 log rank; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Two-year survival curves.

Discussion

Current UK referral guidelines originally developed from the notion that upper GI cancer was rare in patients under the age of 55 years, particularly in those presenting with uncomplicated dyspepsia.5,6 More recent evidence suggests that 10–20% of oesophageal adenocarcinoma occur in the young.7,8 Results from this study identified over 100 patients with oesophageal or gastric cardia adenocarcinoma under the age of 55 years across 17 trusts over a 1-year period.

There is debate regarding whether younger patients present with different symptoms compared to their older counterparts. For instance, in one study, patients under the age of 50 years usually presented with dysphagia and were symptomatic for a longer time prior to diagnosis. In our study, symptoms at presentation were broadly similar between the two groups. Although time from GP referral to first hospital diagnosis was significantly longer in the under 55-year group, this is unlikely to be clinically relevant.

This study confirms that, irrespective of age, the majority of patients with oesophagogastric cancer present late and have a poor prognosis. Disease stage at presentation was broadly similar between the two groups, with the majority of patients presenting with stage III or stage IV disease. Patients under 55 years had an improved 2-year survival compared to those over 55 years, and this is in contrast to previous studies which have shown that survival of young patients with these tumours is worse compared to their older counterparts,9,10 particularly for gastric cancer. Our results are likely to be as a consequence of more patients in the under 55-year group undergoing a curative treatment pathway compared to older individuals who may have had substantial co-morbidity. Furthermore, younger patients are more likely to tolerate multimodal treatment incorporating combinative chemotherapy with radiotherapy often in conjunction with surgery.

This study has demonstrated that a minority of cancers are identified through the 2-week-wait pathway, although this proportion is smaller in the under 55-year group. Moreover, the current dyspepsia referral guidelines are failing to detect early-stage disease, irrespective of age. Dyspepsia itself is a ubiquitous problem, although the term is not understood by many patients and remains a vague term in medical practice. Therefore, many, if not most, patients with dyspepsia will consult their GP as a result of their symptoms.11 Furthermore, a recent retrospective study has identified that the use of alarm symptoms in dyspeptics as a means of determining who should have an endoscopy invariably identifies patients with advanced, and often incurable, oesophagogastric cancer.12

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy remains the most effective diagnostic test for oesophageal and gastric cancer. Although there has been much in the literature about improving access to endoscopy for younger patients, it is not clear whether this would necessarily improve mortality figures. Furthermore, there are potentially harmful risks associated with this invasive test if employed for all patients with new onset dyspepsia. A recent study has suggested that only males would benefit from a reduction in age threshold for endoscopy in terms of earlier diagnosis.13

Since survival is highly dependent on clinicopathological stage at presentation, more effective strategies are urgently needed in order to detect early upper gastrointestinal cancer. The major dilemma is how to decide on initial management in young patients without alarm symptoms. Clearly, there would be some individuals at higher risk of developing cancer than others and these patients would benefit from careful stratification at the primary care level. It may be possible to identify more discriminating early symptoms for oesophageal and gastric cancer than the rather vague symptom of dyspepsia. Such symptom nonograms have been investigated previously but have failed to demonstrate adequate sensitivity or specificity for clinical use.14 Recently, a non-endoscopic immunocytological screening test that could be used in primary care has been successfully utilised to identify luminal biomarkers of Barrett's oesophagus, the precursor of oesophageal adenocarcinoma.15 Further research is needed in the area of early diagnosis of oesophagogastric cancer.

Conclusions

These results have confirmed that patients with oesophagogastric cancer present late and have a poor prognosis irrespective of their age. However, those under the age of 55 years have a better prognosis than their older counterparts. Further research is urgently needed to identify potential strategies for the early diagnosis of oesophagogastric cancer.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the South West Cancer Intelligence Service.

References

- 1.Guardino JM, Khandwala F, Lopez R, Wachsberger DM, Richter JE, Falk GW. Barrett's esophagus at a tertiary care center: association of age on incidence and prevalence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2187–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portale G, Peters JH, Hsieh CC, Tamhankar AP, Almogy G, et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients < or = 50 years old: delayed diagnosis and advanced disease at presentation. Am Surg. 2004;70:954–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Post PN, Siersema PD, Van Dekken H. Rising incidence of clinically evident Barrett's oesophagus in The Netherlands: a nation-wide registry of pathology reports. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:17–22. doi: 10.1080/00365520600815654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer, Ref CG27. London: NICE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillen D, McColl KE. Does concern about missing malignancy justify endoscopy in uncomplicated dyspepsia in patients aged less than 55? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:75–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christie J, Shepherd NA, Codling BW, Valori RM. Gastric cancer below the age of 55: implications for screening patients with uncomplicated dyspepsia. Gut. 1997;41:513–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canga C, 3rd, Vakil N. Upper GI malignancy, uncomplicated dyspepsia, and the age threshold for early endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:600–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster MA, Attwood SE. Current guidelines fail young patients with oesopha gogastric cancer. Gut. 2002;51:296–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.2.296-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badwe RA, Patil PK, Bhansali MS, Mistry RC, Juvekar RR, Desai PB. Impact of age and sex on survival after curative resection for carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 1994;74:2425–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941101)74:9<2425::aid-cncr2820740906>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maehara Y, Watanabe A, Kakeji Y, Emi Y, Moriguchi S, et al. Prognosis for surgically treated gastric cancer patients is poorer for women than men in all patients under age 50. Br J Cancer. 1992;65:417–20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, Cook MB, Axon AT, Moayyedi P. Who consults with dyspepsia? Results from a longitudinal 10-yr follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:957–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowrey DJ, Griffin SM, Wayman J, Karat D, Hayes N, Raimes SA. Use of alarm symptoms to select dyspeptics for endoscopy causes patients with curable esophagogastric cancer to be overlooked. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1725–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0679-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Bianco MA, Russo P, et al. Combination of age and sex improves the ability to predict upper gastrointestinal malignancy in patients with uncomplicated dyspepsia: a prospective multi-centre database study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:784–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerson LB, Edson R, Lavori PW, Triadafilopoulos G. Use of a simple symptom questionnaire to predict Barrett's esophagus in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2005–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lao-Sirieix P, Boussioutas A, Kadri SR, O'Donovan M, Debiram I, et al. Non-endoscopic screening biomarkers for Barrett's oesophagus: from microarray analysis to the clinic. Gut. 2009;58:1451–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.180281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]