Abstract

Background

There is evidence that Candida colonization contributes to increasing invasion of candidiasis in hospitalized neonates. Few studies investigated the epidemiology and risk factors of Candida colonization among hospitalized and non-hospitalized infants. This prospective study investigated the major epidemiological characteristics of Candida species colonizing oral and rectal sites of Jordanian infants.

Methods

Infants aged one year or less who were examined at the pediatrics outpatient clinic or hospitalized at the Jordan University Hospital, Amman, Jordan, were included in this study. Culture swabs were collected from oral and rectal sites and inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose agar. All Candida isolates were confirmed by the Remel RapID yeast plus system, and further investigated for specific virulence factors and antifungal susceptibility MIC using E-test. Genotyping of C. albicans isolates was determined using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis method.

Results

A total of 61/492 (12.4%) infants were colonized with Candida species by either their oral/rectal sites or both. Rectal colonization was significantly more detected than oral colonization (64.6% verses 35.4%), particularly among hospitalized infants aged more than one month. The pattern and rates of colonization were as follows: C. albicans was the commonest species isolated from both sites and accounted for 67.1% of all isolates, followed by C.kefyr (11.4%), each C. tropicalis and C. glabrata (8.9%) and C. parapsilosis (3.8%).

A various rates of Candida isolates proved to secrete putative virulence factors in vitro; asparatyl proteinase, phospholipase and hemolysin. C. albicans were associated significantly (P < 0.05) with these enzymes than other Candida species. All Candida isolates were susceptible to amphotericin B and caspofungin, whereas 97% of Candida species isolates were susceptible to fluconazole using E-test.

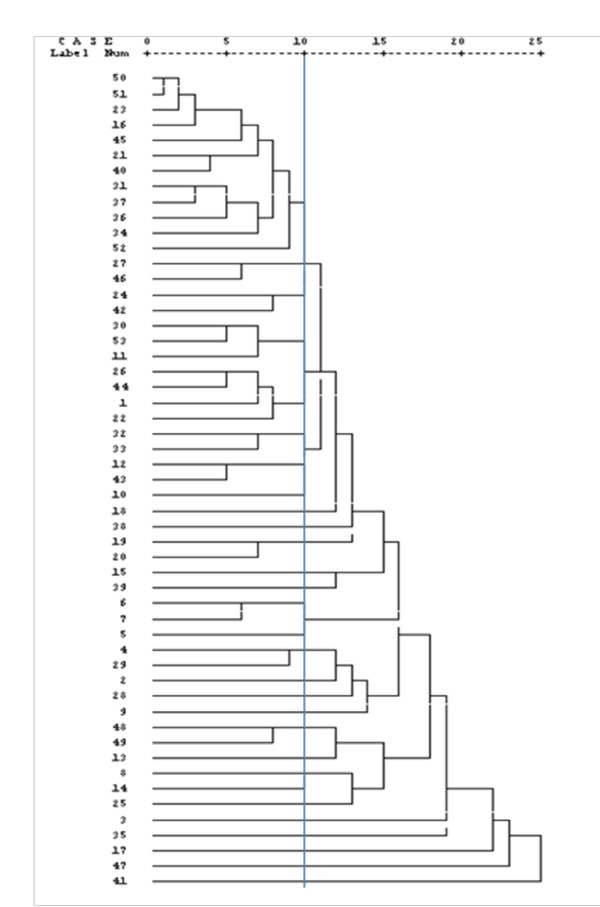

The genetic similarity of 53 C. albicans isolates as demonstrated by dendrogram revealed the presence of 29 genotypes, and of these one genotype accounted for 22% of the isolates.

Conclusion

This study presents important epidemiological features of Candida colonization of Jordanian infants.

Keywords: Candida colonization, virulence, genotypes, antifungal susceptibility

Background

Candida colonization of infants is a risk factor for developing candidiasis, especially in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [1-4]. During the past decade colonization and candidaemia with non-albicans Candida species has risen dramatically with high rates of carriage in hospitalized infants including neonates admitted to NICU [2,5,6].

It is generally observed that most infant candidiasis is thought to be endogenously acquired through prior colonization of different parts of the body, while other studies reported that certain outbreaks of Candida infection were caused by nosocomial infection in neonatal intensive care units [7-10].

The potential pathogenesis of Candida species appears to depend on many immunological and environmental host factors and strain virulence factors, including hyphae and biofilm formation, drug resistance and the production of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes [11-15].

Phenotyping and genotyping of Candida isolates are important features can be used to investigate the common genotypes and possible route of transmission and infection within hospitals and community, especially molecular typing of Candida isolates is highly useful tool in detection source of nosocomial infections [16-19]. This study was carried out to investigate the major epidemiological characteristics of Candida colonizing hospitalized and non-hospitalized Jordanian infants.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted at the Jordan University Hospital over a period of 10-month; from March 2008 to December 2008. The study has been approved by the high graduate committees of the Faculty of Medicine, and ethics committee of Jordan Hospital University and Faculty of Graduate studies/University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan. Verbal consent was obtained from all mothers of infants after explaining the purpose of the study.

Study participants

A total of 492 infants (aged one year or less) were included in this study over a period of 10-month (2008-2009) as follows: Group 1; 265 neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Group 2; 37 infants admitted to pediatric ward (PW) due to urinary tract or kidney problems. Group 3; 190 infants examined in pediatric outpatients clinic. For each patient important demographic characteristics were recorded on special study form, and all hospitalized neonates and infants were observed for developing candidaemia.

Specimen collection

Pre-wetted cotton swabs with sterile saline were used to collect culture specimens from oral and rectal sites of each infant. For neonates in the NICU; oral and rectal swabs were collected within 24 hr of birth, day seven and after every one week until the baby discharged or died. Fresh oral and rectal specimens were handled and inoculated directly on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates (SDA, Oxoid, Ltd, Basingstoke, UK) which supplemented with chloramphenicol (0.05 g/l) and incubated at 37°C for 24-48 hrs.

Mycological investigations

All growth of yeast-like colonies was subsequently identified by subculture 2-3 representative colonies on a CHROMagar Candida medium (Oxoid, Ltd, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated at 37°C for 24-48 hr. Candida growth was identified by detection of various color characteristics on CHROMagar Candida plates [20]. All Candida species isolates were confirmed by the Remel RapID yeast plus system (Remel Inc, Lenexa, KS). Reference standard strains of C. albicans (ATCC 90028), C. glabrata (ATCC 22553) and C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) were subcultured on the same medium as controls.

Detection of extracellular production of aspartyl proteinases was made for all Candida isolates by demonstration and measurement of the clear zone of proteolysis around Candida colony growth in bovine serum albumin agar [20]. Production of extracellular phospholipaes activity was estimated by growing Candida on egg-yolk agar and observing the precipitation zone around the Candida colony growth [12]. Beta-hemolysin production was evaluated using a fresh human blood agar plate and after incubation for 48 hr [20]. Reference strains of C. albicans (ATCC 10231) served as positive control for proteinase and phospholipaes assays and C. albicans (ATCC 90028) served as positive control for haemolysin assay.

Antifungal susceptibility test

Etests were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (AB Biodisk, Sweden). The antifungal agents used were amphotericin B, fluconazole and caspofungin. A quality control C. albicans strain (ATCC 90028) was included.

Genotyping

Determination of Candida genotype was performed using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis method and PCR amplification with three random oligonucleotides single primers T3B primer 5'-d(AGG TCG CGG GTT CGA ATCC) 3' [21]. RSD 10 primer 5'-d(CCG CAG CCA)-3' and RSD 12 primer 5'-d(GGT CCG TGT TTC AAG ACG)-3' [22].

Statistical analysis

All Data analysis were performed using the computerized statistical program Statistical Package of Social Science program (SPSS, version 16, USA) and was used to determine the P values and investigated phylogenetic tree (dendrogram) showing the genetic relatedness among the isolates which was constructed based on genetic similarities. In all statistical tests, the differences were considered to be statistically significant if p-value (< 0.05).

Results and Discussion

Demographic characteristics of 492 investigated infants with total positive and negative Candida species cultures are shown in Table 1. This study showed that Candida colonization was recorded in 12.4% of all infants, and rectal site was significantly more colonized than oral site (64.6% vs 35.4%; P < 0.05). Candida colonization was significantly more prevalent among hospitalized infants aged ≥ 30 days than neonates admitted to NICU (15.3% vs 10.6%). Despite this fact only one case of candidaemia has been detected to be associated with Candida colonization in a hospitalized neonate over the 10-month study period (Table 1). The study also demonstrated that age, gender, the duration of hospitalization, previous antibiotic treatment of infants were not a significant risk factor associated with Candida colonization (Table 1). C. albicans was the commonest species (67.1%) isolated from both oral and rectal sites of infants, whereas other non-albicans Candida species accounted for one third of isolates (Table 2). It is difficult to correlate the results of this study with most other studies which have been investigated mainly the relationship between risk factors of Candida colonization and developing of Candida infections in neonates hospitalized in NICU [1,3-5,9]. However, a study in Greece has found that Candida species colonization was detected in 12.1% of neonates during a 12-month period, and C. albicans was isolated from 42% of colonized neonates. In addition, candidemias were diagnosed more in colonized neonates (6.9%) as compared with 0.76% of noncolonized neonates (P = 0.002)[3]. A recent study from Brazil reported that 19% of the neonates were colonized by Candida species which were divided equally between C. albicans (50%) and non-albicans Candida (50%) [1]. The increased colonization of non-albicans Candida species as well as their cause of candidaemia in neonates and adult Jordanian patients has been shown to be similar to other studies from various countries [1,2,6,4,7,23].

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of 492 investigated infant with Positive Candida colonization from oral/rectal or both specimens

| Variables |

Candida Colonized infants No. (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age by group | ||

| 0 - 28 days (neonates) | 28/265(10.6) | 0.135 |

| 29 days - 1 year (infants) | 33/227(15.3) | |

| Total | 61/492(12.4) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 35/256 (13.7) | 0.764 |

| Female | 26/236(11.0) | |

| Patients by group | ||

| NICU | 18/265(6.8)* | 0.001 |

| Pediatric ward | 12/37(32.4) | |

| Outpatients | 31/190(16.3) | |

| Hospital Stay | ||

| 1 - 7 days | 13/138(8.6) | 0.373 |

| 8 - 30 days | 13/116(10.1) | |

| > 30 days | 4/18(18.2) | |

| Antibiotic treatment | ||

| Yes | 30/285(10.5) | 0.139 |

| No | 31/207(15.0) |

* One hospitalized neonate was his oral and rectal sites colonized

with C. albicans has developed Candidemia

Table 2.

Distribution of Candida species isolates colonizing oral and rectal sites of 61 infant patients*

| Type of Candida | Oral colonization No. (%) |

Rectal colonization No. (%) |

Total colonization No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C.albicans | 21 (75.1) | 32 (62.7) | 53 (67.1) |

| C.kefyr | 1 (3.6) | 8(15.7) | 9 (11.4) |

| C.tropicalis | 2 (7.1) | 5 (9.8) | 7 (8.9) |

| C.glabrata | 2 (7.1) | 5 (9.8) | 7 (8.9) |

| C.parapsilosis | 2 (7.1) | 1 (2.0) | 3 (3.8) |

| Total | 28 (35.4) | 51 (64.6)** | 79 (100) |

* Includes 18 infant patients have both oral and rectal colonization at the same time.

** Significant (P < 0.05)

All Candida isolates in this study were 100% susceptible to amphotericin B and caspofungin, while susceptibility to fluconazole was observed only in 5/7 C. glabrata isolates (Table 3). These results are similar to some extent to a previous study published from Jordan [23].

Table 3.

Antifungal susceptibility results of the 79 oral and rectal Candida isolates

| Candida species (no. of isolates) |

% susceptible(MIC range/mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B | Fluconazole | Caspofungein | |

|

C. albicans

(53) |

100 (0.002 - 1.5) |

100 2-16)) |

100 (0.064-1) |

|

C. glabrata

(7) |

100 (0.002 - 0.75) |

71.6* (4-48) |

100 0.25-75)) |

|

C. kefyr

(9) |

100 0.5 - 1.5)) |

100 1.5 - 3)) |

100 (0.125-0.75) |

|

C. tropicalis

(7) |

100 (0.125 - 75) |

100 (2-4) |

100 (0.25-1) |

|

C. parapsilosis

(3) |

100 (0.38-1.0) |

100 (1-6) |

100 (0.5-75) |

* 2/7 of C.glabrata isolates were resistant to fluconazol

The present study has detected a significant production of putative virulence enzymes of phospholipase, protease in most C. albicans isolates from oral and rectal specimens, compared to production of these enzymes among non-albicans Candida species (Table 4). The expression of hemolysin activity was also significant among the majority of C. albicans, C. tropicals, C. glabrata compared to other Candida isolates. However, no significant relationship has been detected between Candida isolates from oral or rectal specimens and exertion of these enzymes or in relation to their antifungal susceptibility. Many studies have suggested that hemolytic activity and hydrolytic enzymes are putative virulence factor contributing to Candida colonization and hematogeneous infection [12,14,15,20,24]. A recent study has shown that the increased pathogenicity of Candida drug-resistant strains for systemic infection was associated with a number of biochemical and physiological changes, including cellular alterations in cell wall polysaccharides, rapid and extensive hypha and biofilm formation [25].

Table 4.

Distribution of proteinase, phospholipase and hemolysin among Candida species isolates

| Enzyme | Candida species | No. of isolates | Positive isolates No. (%) |

Negative isolates No. (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinase | C. albicans | 53 | 49 (92.5) | 4 (7.5) | 0.004 |

| C. kefyr | 9 | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | ||

| C. tropicalis | 7 | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| C. glabrata | 7 | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| C. parapsilosis | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Total | 79 | 64 (81.0) | 15 (19.0) | ||

| Phospholipae | C. albicans | 53 | 48 (90.6) | 5 (9.4) | 0.0001 |

| C. kefyr | 9 | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | ||

| C. tropicalis | 7 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | ||

| C. glabrata | 7 | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | ||

| C. parapsilosis | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Total | 79 | 61 (77.2) | 18 (22.8) | ||

| Hemolysin | C. albicans | 53 | 45 (84.9) | 8 (15.1) | 0.0012 |

| C. kefyr | 9 | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | ||

| C. tropicalis | 7 | 7 (100) | 0 | ||

| C. glabrata | 7 | 6(85.7) | 1(14.3) | ||

| C. parapsilosis | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Total | 79 | 62 (78.5) | 17 (21.5) |

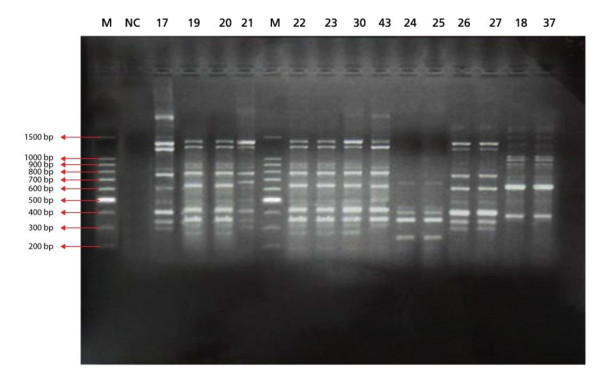

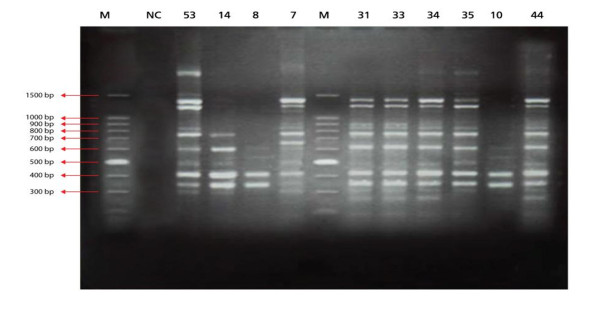

The results of RAPD patterns of C. albicans isolates as demonstrated in constructed dendrogram suggest that at least one genotype was prevalent (22.6%) among all colonized infants either hospitalized or not (Figure 1,2 &3). It has been proved tha RAPD is a very useful method for evaluating and comparing the genetic profiles of C. albicans clones [22].

Figure 1.

Dendrogram of 53 C. albicans isolates.

Figure 2.

RAPD-PCR patterns generated by C. albicans isolates using T3B primer, M, 100 bp PCR DNA marker; Lane 1, negative PCR blank; Numbered lanes show patterns of different representative C. albicans isolates.

Figure 3.

RAPD-PCR patterns generated by C. albicans isolates using RSD 10 primer, M, 100 bp PCR DNA marker; Lane NC, negative PCR blank. Numbered Lanes show patterns of different representative C. albicans isolates.

Conclusion

This study contributes to increase our understanding of the epidemiology of Candida colonization in neonates and infants whether hospitalized or not.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AS and EM have written the conception and design of the study and drafted the final manuscript for publication. EM and KA have supervised all clinical investigations and data collection of the examined infants. SI and AS were responsible for performing all laboratory tests, data analysis and statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Shireen Y Issa, Email: pathol@ju.edu.jo.

Eman F Badran, Email: emantaj@hotmail.com.

Kamal F Akl, Email: kachbl@yahoo.com.

Asem A Shehabi, Email: ashehabi@ju.edu.jo.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by grant from the Dean of Research

(No. 10/2008-2009), University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan.

References

- Borges RM, Soares LR, de Brito CS, de Brito DV, Abdallah VO, Filho PP. Risk factors associated with colonization by Candida spp in neonates hospitalized in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2009;42(4):431–5. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822009000400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhi S, Rao R, Chakrabarti A. Candida colonization and candedemia in a pediatric intensive care unit, Pediatric. Crit Care Med. 2008;9(1):91–95. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000298643.48547.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki E, Evdoridou J, Pouliou T, Bibashi E, Panagopoulou P, Filioti J, Benos A, Sofianou D, Kremenopoulos G, Roilides E. Fungal colonization in the neonatal intensive care unit: risk factors, drug susceptibility, and association with invasive fungal infections. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24(2):127–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan P, Eddama O, Weisman LE. Patient isolation measures for infants with candida colonization or infection for preventing or reducing transmission of candida in neonatal units. Cochrane Database Syst Rev J. 2007. p. CD006068. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baradkar VP, Mathur M, Kumar S, Rathi M. Candida glabrata: Emerging pathogen in neonatal sepsis. Annals Tropical Medicine Public Health. 2008;1(1):5–8. doi: 10.4103/1755-6783.43070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badran EF, Al Baramki JH, Al Shamyleh A, Shehabi A, Khuri-Bulos N. Epidemiology and clinical outcome of candidemia among Jordanian newborns over a 10-year period. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:1–6. doi: 10.1080/00365540701477550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundsdottir LR, Erlendsdottir H, Haraldsson G, Guo H, Xu J, Gottfredsson M. Molecular Epidemiology of Candidemia: evidence of clusters of smoldering nosocomial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(2):17–24. doi: 10.1086/589298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blot S, Dimopoulos G, Rello J, Vogelaers D. Is Candida really a threat in the ICU? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14(5):600–4. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32830f1dff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PB, Steinbach WJ, Benjamin DK. Neonatal Candidiasis. Infect dis clin North Am. 2005;19:603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendel CM. Colonization and epithelial adhesion in the pathogenesis of neonatal candidiasis. Semin Perinatol. 2003;27(5):357–364. doi: 10.1016/S0146-0005(03)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thein ZM, Seneviratne CJ, Samaranayake YH, Samaranayake LP. Community lifestyle of Candida in mixed biofilms: a mini review. Mycoses. 2009;52(6):467–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang CS, Chu FC, Leung WK, Jin LJ, Samaranayake LP, Siu SC. Phospholipase, proteinase and haemolytic activities of Candida albicansisolated from oral cavities of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:1393–1398. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzual I, Riggle P, Hadley S, Kumamoto CA. Biofilm formation by fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains is inhibited by fluconazole. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(3):441–50. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokce G, Cerikcioglu N, Yagci A. Acid proteinase, phospholipase, and biofilm production of Candida species isolated from blood cultures. Mycopathologia. 2007;164:265–269. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller M, Borelli C, Korting HC, Hube B. Hydrolytic enzymes as virulence factors of Candida albicans. Mycoses. 2005;48(6):365–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asbeck EC, Markham AM, Clemons KV, Stevens DA. Candida parapsilosis fungemia in neonates: genotyping results suggest healthcare workers hands as source, and review of published studies. Mycopathologia. 2007;164:287–293. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires-Gonc RH, Miranda ET, Baeza LC, Matsumoto MT, Zaia JE, Mendes-Giannini MJS. Genetic relatedness of commensal strains of Candida albicans carried in the oral cavity of patients' dental prosthesis users in Brazil. Mycopathologia. 2007;164:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong PP, Chieng DC, Low LY, Hafeez A, Shamsudin MN, Ng KP. Recurrent candidaemia in a neonate with Hirschsprung's disease: fluconazole resistance and genetic relatedness of eight Candida tropicalis isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:423–428. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viviani MA, Cogliati M, Esposto MC, Prigitano A, Anna Tortorano M. Four-Year Persistence of a Single Candida albicans Genotype Causing Bloodstream Infections in a Surgical Ward Proven by Multilocus Sequence Typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(1):218–221. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.218-221.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehabi AA, Nazzal SA, Dajani N. Putative Virulence Factors of Candida species Colonizing Respiratory Tracts of Patients. Microb Ecol Health and Dis. 2004;16:214–217. doi: 10.1080/08910600410025419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Correia A, Sampaio P, Almeida J, Pais C. Study of Molecular Epidemiology of Candidiasis in Portugal by PCR Fingerprinting of Candida Clinical Isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(12):5899–5903. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5899-5903.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaranayake LP, Dassanayake RS, Yau JYY, Tsang WK, Cheung BPK, Yeung KWS. Genotypic shuffling' of sequential clones of Candida albicans in HIV-infected individuals with and without symptomatic oral candidiasis. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:349–359. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.04972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar-Odeh NS, Shehabi AA. Oral Candidosis in patients with removable dentures. Mycosis. 2003;46:187–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlaneto-Maia L, Specian AF, Bizerra FC, Oliveira MT, Furlaneto MC. In Vitro Evaluation of Putative Virulence Attributes of Oral Isolates of Candida spp. Obtained from Elderly Healthy Individuals. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:209–217. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angiolella L, Stringaro AR, De Bernardis F, Posteraro B, Bonito M, Toccacieli L, Torosantucci A, Colone M, Sanguinetti M, Cassone A, Palamara AT. Increase of virulence and its phenotypic traits in drug-resistant strains of Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(3):927–36. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01223-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]