Summary

Whereas mammalian cells and most other organisms can synthesize polyamines from basic amino acids, the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi is incapable of polyamine biosynthesis de novo and therefore obligatorily relies upon putrescine acquisition from the host to meet its nutritional requirements. The cell surface proteins that mediate polyamine transport into T. cruzi, as well as most eukaryotes, however, have by-in-large eluded discovery at the molecular level. Here we report the identification and functional characterization of two polyamine transporters, TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2, encoded by alleles from two T. cruzi haplotypes. Overexpression of the TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 genes in T. cruzi epimastigotes revealed that TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 were high-affinity transporters that recognized both putrescine and cadaverine but not spermidine or spermine. Furthermore, the activities and subcellular locations of both TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 in intact parasites were profoundly influenced by extracellular putrescine availability. These results establish TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 as key components of the T. cruzi polyamine transport pathway, an indispensable nutritional function for the parasite that may be amenable to therapeutic manipulation.

Introduction

Trypanosoma cruzi is a protozoan parasite that is the aetiological agent of Chagas’ disease, a devastating and often fatal infection of the cardiovascular and gastrointestinal systems that is endemic and epidemic in large portions of Central and South America and also present in the USA (Beard et al., 2003; Moncayo and Ortiz Yanine, 2006; Teixeira et al., 2006). The life cycle of T. cruzi is complex. The parasite is found as the non-infective but highly replicative epimastigote in the digestive tract of its haematophagous insect vector, the triatomid bug, and is excreted in the insect’s feces as the infective but non-replicative metacyclic trypomastigote. The infection of a mammalian host occurs when the contaminated excreta are deposited near and introduced through the bite wound. Once in the bloodstream, the trypomastigotes infect a variety of host cell types and transform to and proliferate intracellularly as amastigotes. These amastigotes are also capable of transforming back to the extracellular trypomastigote, a metamorphosis that allows the parasite to invade other host cells and to disseminate the parasite to uninfected triatomatids, thereby completing the parasite life cycle (Kollien and Schaub, 2000).

Chagas’ disease has two stages; acute and chronic. The acute stage is relatively benign, often asymptomatic, and usually resolves in 2–3 months. However, ~30% of individuals infected with T. cruzi progress into the chronic, incurable and deadly phase of the disease. This chronic phase of Chagas’ disease is characterized by the insidious destruction of the myocardium and ion conduction systems of the heart. Gastrointestinal involvement is also observed in Chagas’ disease. Because there are no effective drugs to cure or even ameliorate chronic Chagas’ disease, the need for finding new drugs and identifying novel drug targets in T. cruzi is acute.

One pathway that has stimulated considerable therapeutic interest for the treatment of parasitic diseases is that for the metabolism of the cationic polyamines, compounds that are indispensable for many life processes including growth and development, protein synthesis and progression through the cell cycle (Igarashi and Kashiwagi, 2000). D,L-α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), a suicide inhibitor of ornithine decarboxylase (Pegg et al., 1987), the enzyme that catalyses the rate limiting step in the polyamine biosynthetic pathway, has shown remarkable curative efficacy in treating African sleeping sickness caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (Van Nieuwenhove et al., 1985; Bacchi and McCann, 1987; Pepin et al., 1987; Burri and Brun, 2003; Docampo and Moreno, 2003), a protozoan parasite of the same genus as T. cruzi. DFMO is also capable of killing other genera of protozoan parasites (Gillin et al., 1984; Aronow et al., 1987; Assaraf et al., 1987; Reguera et al., 1995; Mukhopadhyay et al., 1996; Sanchez et al., 1997). Moreover, inhibitors of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase, the enzyme that provides the aminopropyl group for spermidine synthesis, are also effective anti-trypanosomal agents (Chang and Dwyer, 1978; Bitonti et al., 1986; 1990; Danzin et al., 1990; Bacchi et al., 1992).

The mechanism by which T. cruzi fulfils its polyamine requirements, however, is strikingly different from that of T. brucei and other organisms that are capable of synthesizing polyamines de novo. Although T. cruzi accommodates sizeable pools of putrescine (1,4-diaminobutane), spermidine and cadaverine (1,5-diaminopentane), a diamine normally restricted to prokaryotes (Hunter et al., 1994; Ariyanayagam and Fairlamb, 1997), the parasite is insensitive to DFMO (Kierszenbaum et al., 1987; Schwarcz de Tarlovsky et al., 1993) and does not possess an intact polyamine biosynthetic pathway. T. cruzi epimastigotes lack both ornithine decarboxylase (Ariyanayagam and Fairlamb, 1997; Carrillo et al., 1999) and arginine decarboxylase (Carrillo et al., 2003; 2004) activities, the enzymes that synthesize putrescine from ornithine and arginine, respectively, and the annotated T. cruzi genome does not accommodate genes encoding either enzyme (El-Sayed et al., 2005; http://tcruzidb.org/). The parasite also lacks arginase, which produces ornithine, but it does express both spermidine synthase (Gonzalez et al., 1992; Heby et al., 2007) and S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (Persson et al., 1998; Kinch et al., 1999) activities that enable the conversion of the putrescine to spermidine. Interestingly, T. cruzi S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase has been shown to be catalytically activated by prozyme, a catalytically inactive homologue of the enzyme, and this heterodimer is in turn activated by putrescine to a similar efficiency as the fully activated T. brucei heterodimeric complex (Willert and Phillips, 2009). Thus, T. cruzi cannot synthesize putrescine de novo, although it can convert the diamine to spermidine, and is absolutely dependent on the acquisition of polyamines from the host milieu. This polyamine salvage pathway obligatorily requires diamine and/or polyamine transport mechanisms.

Robust putrescine and spermidine transport activities have been detected in intact T. cruzi epimastigotes by several groups (Le Quesne and Fairlamb, 1996; Gonzalez et al., 2001). This putrescine transport activity is saturable, exhibits high affinity for both putrescine and cadaverine and requires a membrane potential for function, although the transporter itself was not identified (Le Quesne and Fairlamb, 1996). Indeed, there exists a profound gap in our basic biochemical knowledge of polyamine transporters, not only in T. cruzi, but also in all eukaryotes (Gonzalez et al., 1992; Le Quesne and Fairlamb, 1996). Although genes encoding polyamine transporters have been cloned from prokaryotes (Gonzalez et al., 1992; Kashiwagi et al., 1996; 1997; Le Quesne and Fairlamb, 1996; Igarashi and Kashiwagi, 1999), until several years ago the only eukaryotic polyamine transporters that had been identified in eukaryotes were polyamine excretion proteins (Igarashi et al., 2001; Tachihara et al., 2005) or intracellular polyamine transporters (Tomitori et al., 2001) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Recently, however, several polyamine transporters that localize to the plasma membrane have been identified in S. cerevisiae, each of which exhibits ligand specificities that include either amino acids, S-adenosylmethionine or urea (Uemura et al., 2007). No polyamine transporters have been functionally identified to date in mammalian systems.

Recently, our group identified and characterized a polyamine transporter from Leishmania major (Hasne and Ullman, 2005), a parasite that is phylogenetically related to T. cruzi. This transporter, LmPOT1, is a high-affinity putrescine-spermidine transporter and was the first cell surface polyamine transporter to be identified in eukaryotic cells (Hasne and Ullman, 2005). Exploiting LmPOT1 as a query sequence, we identified two LmPOT1 orthologues within the T. cruzi genome, TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2, each of which encodes a candidate polyamine permease and appears to be derived from distinct T. cruzi haplotypes. In a very preliminary communication, Carrillo et al. (Carrillo et al., 2006) have shown that the mRNA from one of these orthologues, TcPOT1.2, apparently induced spermidine transport in Xenopus laevis oocytes. We now report that both TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 are functional putrescine-cadaverine transporters and that transporter function and localization can be regulated by the polyamine content of the extracellular milieu. These diamine permeases are of considerable biochemical and therapeutic significance because they enable the parasite to overcome their distinctive inability to synthesize polyamines de novo and offer a rational paradigm for selectively targeting T. cruzi infections through the inhibition of this essential transport function.

Results

TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 are alleles from different T. cruzi haplotypes

TcPOT1.1 (EU544169) and TcPOT1.2 (FJ204167) were initially identified within the T. cruzi genome database, TcruziDB (http://tcruzidb.org/tcruzidb/), after a Tblastn search using LmPOT1 (AAW52506) as the query sequence. Both genes are heterozygous alleles located on chromosome 11; TcPOT1.1 belongs to the Esmeraldo-like haplotype and TcPOT1.2 to the non-Esmeraldo-like haplotype present in the CL Brener hybrid reference strain that was sequenced in the T. cruzi genome project (http://tritrypdb.org/tritrypdb/). The TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 open reading frames predict polypeptides of 613 and 627 amino acids, respectively, with 94.7% identity between the two primary structures. The differences in amino acids between the two sequences are distributed throughout the two transporters except for a cluster of 14 extra amino acids located at the C-terminal end of TcPOT1.2 (Fig. S1A). Pairwise alignments between TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 and LmPOT1 or the E. coli polyamine transporter, PotE (Kashiwagi et al., 1997), revealed 41.3% amino acid identities between the T. cruzi proteins and the L. major orthologue (Fig. S1A) but only a 12.8% identity to PotE. LmPOT1, TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 each encompassed two conserved signature residues corresponding to Trp201 and Glu207 in the E. coli PotE sequence, two amino acids that are known to be critical for putrescine recognition by PotE (Kashiwagi et al., 2000) (Fig. S1B). Five putative N-linked glycosylation sites (Asn145, 182, 226, 376, 545) and two putative O-linked glycosylation sites (Thr368 and Ser541) were predicted within the TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 polypeptide sequences using web resources provided by Motif Scan (Hulo et al., 2008) and DictyOGlyc (Gupta et al., 1999). Hydropathy profiles for TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 performed using HMMtop algorithms (Tusnady and Simon, 1998) predicted 12 putative transmembrane domains with the NH2-terminal and C-termini envisaged to be intracellular (Fig. S1A).

TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 transport putrescine and cadaverine

The ligand specificities of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 were assessed by overexpressing the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP, pTEX-TcPOT1.1, pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP and pTEX-TcPOT1.2 plasmids in wild-type T. cruzi epimastigotes. Two control cell lines were used. One control transfectant line encompassed an unrelated gene, TcGRASP, that was overexpressed from the pTEX-TcGRASP::GFP vector. TcGRASP encodes the T. cruzi paralogue for the putative Golgi reassembly stacking protein (GRASP) (Barr et al., 1997) and is unlikely to be involved in the cellular polyamine transport process. The second control cell line expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP) alone from pTEX-GFP.

Putrescine uptake was elevated ~4- and ~12-fold in the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP and pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP transfectants, respectively, compared with the pTEX-TcGRASP::GFP transfectant control (Fig. 1A and B). The presence of the C-terminal GFP tag on these transporters did not seem to affect putrescine transport capabilities of either TcPOT1.1 or TcPOT1.2 as comparable augmentations of putrescine transport over that of control parasites were observed in T. cruzi transfected with either tagged or untagged TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 (Fig. 1A and B). Putrescine uptake in all T. cruzi transfectants was linear with time over the 20 s transport assay (data not shown). Saturable Michaelis-Menten kinetics for putrescine uptake were obtained over a range of putrescine concentrations. The results revealed TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 to be high-affinity putrescine transporters with apparent Km values of 158 ± 18 nM for TcPOT1.1 and 385 ± 34 nM for TcPOT1.2 and Vmax values of 6.3 ± 1.0 pmol per 108 cells per second and 9.4 ± 2.4 pmol per 108 cells per second respectively (Fig. 1C). In contrast, no increase in the uptake of either spermidine or spermine was detected in T. cruzi epimastigotes transfected with pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP or pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP compared with the control transfectants (data not shown).

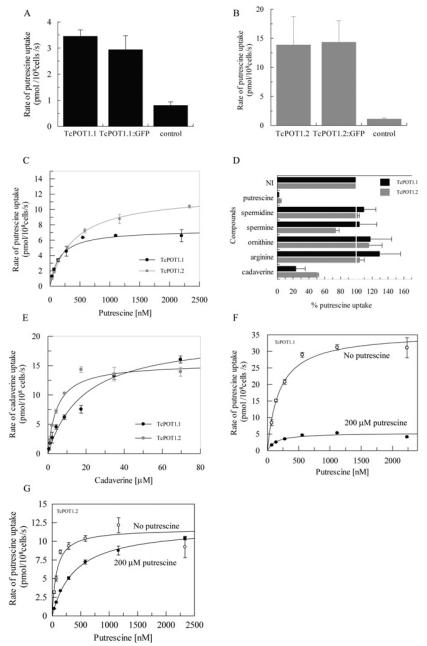

Fig. 1.

Functional characterization of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 in T. cruzi epimastigotes.

A. Comparison of the abilities of T. cruzi epimastigotes expressing either pTEX-TcPOT1.1 (TcPOT1.1), pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP (TcPOT1.1::GFP) or pTEX-TcGRASP::GFP (control) to take up 417 nM [3H]putrescine. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

B. Comparison of the abilities of T. cruzi epimastigotes expressing either pTEX-TcPOT1.2 (TcPOT1.2), pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP (TcPOT1.2::GFP) or pTEX-GFP (control) to take up 484 nM [3H]putrescine. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

C. Michaelis-Menten formulation of putrescine uptake rates obtained for T. cruzi epimastigotes expressing either pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP (●) or pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP ( ) that had been grown in SDM-79 containing 10% FBS and 200 μM putrescine. Values for endogenous transport in control pTEX-TcGRASP::GFP- or pTEX-GFP-transfected parasites were subtracted from the experimental rates.

) that had been grown in SDM-79 containing 10% FBS and 200 μM putrescine. Values for endogenous transport in control pTEX-TcGRASP::GFP- or pTEX-GFP-transfected parasites were subtracted from the experimental rates.

D. Inhibition profile for TcPOT1.1- and TcPOT1.2-mediated putrescine transport. The ability of the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP and pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP transfectants to take up 0.5 μM [3H]putrescine was evaluated in the presence of a variety of structurally related non-radiolabelled compounds, each at a concentration of 50 μM. Results are plotted as a percentage of putrescine uptake obtained without inhibitor (NI). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

E. Abilities of epimastigotes transfected with either pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP or pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP and grown in putrescine-supplemented SDM-79 medium to take up [14C]cadaverine over a range of cadaverine concentrations. Uptake rates obtained with the control pTEX-TcGRASP::GFP transfectant were subtracted from experimental data points. Data were fitted to a Michaelis-Menten algorithm to determine apparent Km and Vmax values.

F. Michaelis-Menten plot of putrescine uptake rates obtained for T. cruzi epimastigotes expressing pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP that had been grown either in SDM-79 containing 10% FBS in the absence (○) or presence (●) of 200 μM putrescine for 48 h. The pTEX-TcGRASP::GFP expressing transfectant served as the control for endogenous transport, and control rates were subtracted from the experimental rates.

G. Michaelis-Menten analysis of putrescine uptake rates obtained for T. cruzi epimastigotes expressing pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP that had been grown either in SDM-79 containing 10% FBS in the absence (○) or presence (●) of 200 μM putrescine for 48 h. The pTEX-GFP expressing transfectant served as the control for endogenous transport and control rates were subtracted from the experimental rates.

To further evaluate the ligand specificity of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2, [3H]putrescine uptake was measured in the presence of a 100-fold excess of one of a variety of non-radiolabelled polyamines or their amino acid precursors. As anticipated, a 100-fold molar excess of non-radiolabelled putrescine essentially abolished [3H]putrescine uptake into the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP or pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP transfectants. In contrast, a 100-fold excess of spermidine, spermine, lysine, arginine or ornithine did not appreciably impact the ability of the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP or pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP transfectants to take up [3H]putrescine (Fig. 1D). Cadaverine, however, also caused a significant inhibition of [3H]putrescine uptake in the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP or pTEX-TcPOT1. 2::GFP transfectants (Fig. 1D). To discern directly whether cadaverine was also a ligand for TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2, the capacity of the epimastigotes transfected with pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP or pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP to transport [14C]cadaverine was determined. As anticipated, [14C]cadaverine uptake was significantly augmented in the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP and pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP transfectants compared with the control cell line (Fig. 1D). This cadaverine uptake was also saturable and exhibited apparent Km values of 18 ± 4 μM and 4 ± 1 μM and Vmax values of 20 ± 2 pmol per 108 cells per second and 14.5 ± 1.3 pmol per 108 cells per second for TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 respectively (Fig. 1E).

Putrescine regulates TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 transport activities

It has been documented that the permeation of certain essential nutrients such as glucose, purines and myo-inositol into trypanosomatid parasites can be modulated by external ligand concentrations (Hall et al., 1996; Seyfang and Landfear, 1999). To determine whether ligand concentration in the extracellular environment also impacted TcPOT1.1- or TcPOT1.2-mediated transport, putrescine kinetics were measured in the T. cruzi pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP and pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP transfectants that had been cultured in either putrescine-supplemented or putrescine-deficient semi-defined medium 79 (SDM-79). T. cruzi epimastigotes can propagate efficiently in the putrescine-deficient medium for at least ~14 days but eventually succumb to polyamine starvation (personal observations). When the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP T. cruzi transfectant was grown in polyamine-deficient SDM-79 for 48 h, the Vmax value for putrescine transport increased ~4–6-fold to 25 ± 12 pmol per 108 cells per second without affecting the affinity of TcPOT1.1 for the ligand (Fig. 1F). The Km and Vmax values for putrescine transport of the pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP transfectant line grown in undefined Liver infusion tryptose (LIT) medium were similar to those obtained with the same parasites grown in SDM-79 to which 200 μM putrescine was added (data not shown). Conversely, when the T. cruzi pTEX-TcPOT1. 2::GFP transfectant was grown in polyamine-deficient SDM-79 for 48 h, the Vmax value was only marginally affected but the Km value decreased about fourfold (Fig. 1G).

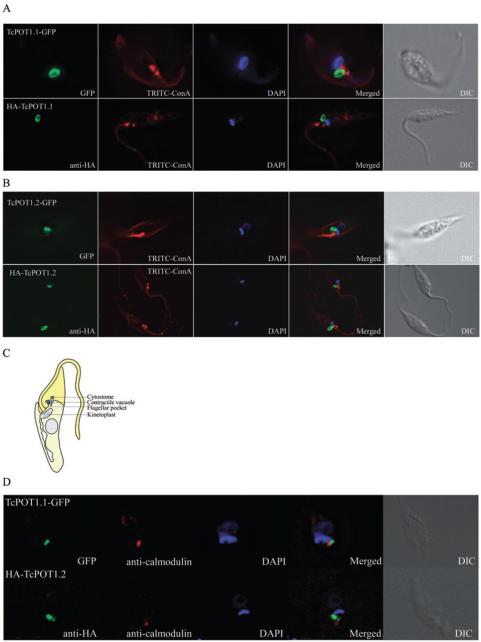

TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 are localized in the vicinity of the flagellar pocket

Fluorescence microscopic analysis of epimastigotes expressing TcPOT1.1::GFP or TcPOT1.2::GFP grown in SDM-79 medium supplemented with 200 μM putrescine revealed that TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 were localized primarily to a ring shape structure located at the anterior end of the parasite adjacent to the base of the flagellum (Fig. 2A and B). A comparable distribution of fluorescence was also observed by indirect immunofluorescence in T. cruzi cell lines expressing HA::TcPOT1.1 and HA::TcPOT1.2 each encoding a chimeric protein tagged at the NH2-terminus with the haemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag (Fig. 2A and B). Three identified subcellular structures in T. cruzi are potentially consistent with this localization: the flagellar pocket, the cytostome and the contractile vacuole complex (Fig. 2A). The flagellar pocket and cytostome are invaginations of the plasma membrane located at the anterior extremity of the parasite, with the flagellar pocket positioned between the base of the flagellum and the kinetoplast and the cytostome situated at the side of the flagellum (Fig. 2C) (Okuda et al., 1999; Gull, 2003; Vatarunakamura et al., 2005). The contractile vacuole, an organelle involved in osmoregulation (Rohloff et al., 2004; Rohloff and Docampo, 2008), is located in close proximity to the flagellar pocket and the cytostome (Fig. 2C). The ring shape fluorescence-pattern observed with TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 is located to the side of the flagellum/kinetoplast alignment suggesting that TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 are not localized to the flagellar pocket itself (Fig. 2A and B). The absence of readily available and specific cellular markers for the T. cruzi cytostome precludes definitive colocalization experiments that could firmly establish a cytostomal localization for TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2. Because Rohloff et al. have demonstrated that calmodulin can be used as a marker for the T. cruzi epimastigote contractile vacuole (Rohloff et al., 2004), colocalization of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 with calmodulin was attempted. However, these experiments did not show colocalization of TcPOT1.1 or TcPOT1.2 with calmodulin intimating that the two transporters are not located at the contractile vacuole (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Localization of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 in T. cruzi epimastigotes grown in putrescine-replete media.

A. and B. Fluorescence images of fixed T. cruzi epimastigotes expressing either a GFP tag fused to the C-terminus of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 (TcPOT1.1-GFP and TcPOT1.2-GFP) or an HA tag fused to the NH2-terminus of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 (HA-TcPOT1.1 and HA-TcPOT1.2). Parasites were propagated in SDM-79 supplemented with 200 μM putrescine.

C. Schematic representation of an epimastigote form of T. cruzi adapted from a drawing by Docampo et al. (2005).

D. Fluorescence images of T. cruzi epimastigotes demonstrating the absence of colocalization of calmodulin, a presumed contractile vacuolar marker (Rohloff et al., 2004) with TcPOT1.1-GFP and HA-TcPOT1.2 implying that the two permeases are not located at the contractile vacuole.

Fluorescence for TcPOT1.1-GFP and TcPOT1.2-GFP (green), TRITC-concanavalin A (red), anti-calmodulin (red) and DAPI (blue) were determined as indicated by the labels in the figure. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images depict the same parasites shown in the fluorescent images.

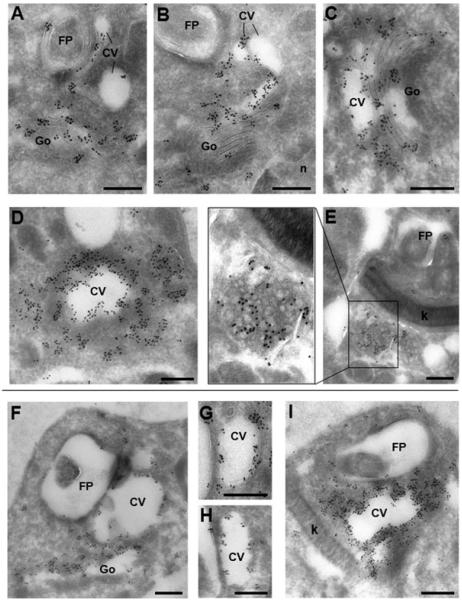

To attempt to clarify the subcellular milieu of the TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 further, immunoelectron microscopy using anti-HA antibodies was implemented on fixed parasites expressing HA::TcPOT1.1 and HA::TcPOT1.2. These experiments revealed the presence of gold particles bound to a tubulo-vesicular structure located in the vicinity of the flagellar pocket with structural features similar to that of the contractile vacuole in both transfectant lines (Fig. 3). In transgenic parasites expressing either HA-TcPOT1.1 or HA-TcPOT1.2, the Golgi apparatus and the limiting membrane of the contractile vacuoles were abundantly labelled suggesting the association of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 with these organelles. A plethora of small vesicles distributed around the contractile vacuole system, possibly the spongiome that has been characterized in T. cruzi and other protozoa (Rohloff and Docampo, 2008), were also positively labelled, implying a dynamic vesicular trafficking and potential recycling of these transporters in the parasites. On several occasions, an unknown ‘spongy’ structure located beneath the kinetoplast was decorated with gold particles in the HA-TcPOT1.1-expressing parasites (Fig. 3E). No gold particles were ever detected on the parasite cell surface, flagellar pocket or the cytostome.

Fig. 3.

Ultrastructural detection of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 in transgenic T. cruzi. Immunogold labelling of HA-TcPOT1.1 (A–E) and HA-TcPOT1.2 (F–I) with anti-HA antibodies. Both transporters were observed in the Golgi apparatus (A–C and F) and the contractile vacuole system close to the flagellar pocket (A–D and F–G), while TcPOT1.1 was also detected in a proximal ‘spongy’ structure of unknown identity (E). CV, contractile vacuole; FP, flagellar pocket; Go, Golgi apparatus; k, kinetoplast; n, nucleus; s, spongiosome. Scale bars are 200 nm.

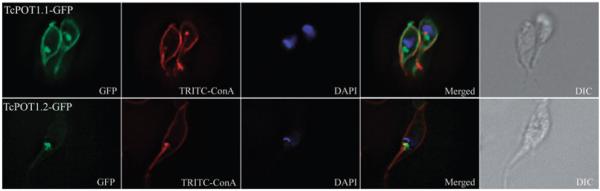

When transfected T. cruzi epimastigotes expressing pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP were shifted into SDM-79 lacking added putrescine, there was a dramatic shift in the localization of TcPOT1.1 from the intracellular milieu that it occupies in the presence of putrescine to the parasite cell surface (Fig. 4). A significantly less remarkable location transfer was observed when the TcPOT1.2::GFP transfectant was propagated in putrescine-deficient SDM-79.

Fig. 4.

Localization of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 in T. cruzi epimastigotes grown in putrescine-deficient medium. Parasites were grown in SDM-79 supplemented with 10% FBS but lacking putrescine. Fluorescence for TcPOT1.1-GFP and TcPOT1.2-GFP (green), TRITC-concanavalin A (red) and DAPI (blue) were ascertained as specified in the figure. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images depict the same parasites shown in the fluorescent images.

Discussion

Because of its inability to synthesize polyamines de novo, polyamine acquisition from the environment through specific polyamine transport mechanisms is an indispensable nutritional process for T. cruzi parasites. We have identified and functionally characterized at the molecular level two polyamine permeases, TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2, both of which are saturable, high-affinity putrescine-cadaverine transporters that do not appear to recognize spermidine or spermine. TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 were initially identified in the published T. cruzi genome sequence (El-Sayed et al., 2005) by virtue of their homology to the polyamine permease of L. major (Fig. S1). Because the reference strain for the T. cruzi sequencing projection, CL Brener, is a complex hybrid of two distinct evolutionary lineages of the parasite (El-Sayed et al., 2005; De Freitas et al., 2006), TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 are heterozygous alleles with 4.4% sequence variation that have been assigned to the Esmeraldo and non-Esmeraldo-like haplotypes respectively.

The substrate specificities of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 are strikingly similar to those of the high-affinity transport system previously characterized in T. cruzi epimastigotes by Le Quesne and Fairlamb (1996). The polyamine transport activities of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 and of intact parasites both exhibited great selectivity towards putrescine and cadaverine and were downregulated by exogenous putrescine (Le Quesne and Fairlamb, 1996). The affinity of TcPOT1.1 for both diamine ligands as measured on T. cruzi overexpressing TcPOT1.1, however, was an order of magnitude greater than that for the polyamine transport activity calculated for epimastigotes (Le Quesne and Fairlamb, 1996). Whether this discrepancy is the result of extensive gene diversity that exists among T. cruzi strains (Macedo et al., 2002), or whether T. cruzi expresses multiple putrescine-cadaverine permeases with different kinetic parameters is not known. The ligand selectivity that we determined for TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 however does not match a previous report that injection of TcPOT1.2 cRNA preferentially mediates spermidine transport in X. laevis oocytes, although putrescine and arginine uptake are also weakly stimulated (Carrillo et al., 2006). The discrepancy in the assigned ligand specificities for TcPOT1.2 [designated TcPAT12 by Carrillo et al. (2006)] could originate from differences in the expression systems employed in the two studies. Attempts to recreate the X. laevis expression system in our laboratory with both TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 were unsuccessful, a failure that we attributed to the intracellular milieu in which the two permeases are found in epimastigotes.

Cadaverine, a diamine generally restricted to prokaryotes, is an unusual ligand for a eukaryotic polyamine transporter. Although cadaverine is not synthesized by T. cruzi or by mammalian cells, the diamine is found in epimastigotes grown in semi-defined media (Algranati et al., 1989, Schwarcz de Tarlovsky et al., 1993). Furthermore, the gut of the triatomid vector is known to contain cadaverine-secreting Actynomyces bacteria that are presumably the source of the micromolar cadaverine concentrations found in the triatomid gut (Hunter et al., 1994). Moreover, T. cruzi, unlike Leishmania and T. brucei, express the metabolic machinery to convert cadaverine to homotrypanothione, an analogue of trypanothione (Hunter et al., 1994; Ariyanayagam and Fairlamb, 1997), the thiol reductant in trypanosomatids that supplants the role of glutathione in mammalian cells. In addition to diamine transport, T. cruzi also possesses the capacity to transport exogenous spermidine. This is accomplished through a facilitated, high-affinity spermidine transporter (Km 0.81 ± 0.22 μM) (Le Quesne and Fairlamb, 1996), but this spermidine transporter remains to be identified. In addition, there is indirect evidence that T. cruzi is capable of taking up extracellular spermine (Ariyanayagam and Fairlamb, 1997). Thus, T. cruzi appears to express a multiplicity of polyamine transporters. Subsequent searches of the T. cruzi genome revealed two additional TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 homologues, but these have, thus far, resisted functional characterization (data not shown). Overall, as previously advanced by Le Quesne and Fairlamb (1996), T. cruzi appears to scavenge diamines (putrescine and cadaverine) and polyamines (spermidine and spermine) via biochemically distinct routes.

When parasites are grown putrescine-replete medium, both TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 are predominantly confined to the anterior end of parasite in an area adjacent to the flagellar pocket. Because knowledge of the structure and function of organelles proximal to the T. cruzi flagellar pocket is quite limited, the precise location of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 cannot be definitively ascertained. Immunoelectron microscopy using antibodies to HA indicated that both TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 were localized to well-defined structures in close proximity of the flagellar pocket, although not in the flagellar pocket itself (Fig. 2). Immunogold labelling of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 was associated with the Golgi apparatus and the contractile vacuolar complex. This contractile vacuolar complex is formed by the contractile vacuole and the spongiome, the latter an array of 60–70 nm tubules surrounding the bladder of the contractile vacuole (Linder and Staehelin, 1979; Rohloff and Docampo, 2008). These organelles are likely to be involved in TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 biosynthesis and ultimate transit of the permeases to the plasma membrane where their function is required, or these organelles could conceivably be involved in a recycling pathway for the polyamine permeases. The fine localization of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 to the contractile vacuole conflicts with our immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 2D) that implied that the diamine permeases were not associated with the contractile vacuole. However, light microscopy is much more limited in its resolution, and the data analysis is predicated on the assumption that calmodulin is a stringent contractile vacuolar marker. Alternatively, calmodulin distribution could be confined to specific compartments of the contractile vacuole complex distinct from those containing TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2.

The ability of TcPOT1.1 and to a smaller extent TcPOT1.2 to cover the entire cell surface when parasites are grown in putrescine-free conditions implies the existence of one or more cellular signalling mechanisms that sense putrescine availability. This accumulation of TcPOT1.1 at the plasma membrane under low putrescine growth conditions correlated with a sizeable augmentation in putrescine transport capability. The mechanism by which this redistribution of TcPOT1.1 occurs remains elusive. Putrescine may influence a TcPOT1.1-protein sorting mechanism or affect TcPOT1.1 stability at the plasma membrane leading to an accumulation of TcPOT1.1 at the parasite cell surface.

Despite the fact that TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 possess the same ligand profile, their augmented capacity to increase putrescine transport as a function of putrescine availability in the medium appears to be regulated in an unusual and complementary manner. TcPOT1.1 responds to putrescine scarcity by increasing the Vmax value for putrescine transport without a concomitant change in the apparent affinity for the diamine. Conversely, the affinity of TcPOT1.2 for putrescine is increased approximately four-fold when epimastigotes are propagated in polyamine-deficient medium, while the corresponding apparent Vmax is unchanged. This unusual alteration in transport kinetics suggests that TcPOT1.2 experiences some unknown underlying post-translational modification or conformational change in response to putrescine accessibility. The distinctive mechanisms by which the two polyamine transport homologues alter their transport kinetics will clearly require further study. It is apparent, however, that T. cruzi can adapt its membrane apparatus for polyamine transport in a fashion that enables the parasite to regulate its polyamine pool at the level of transport.

Experimental procedures

Chemicals and reagents

[2,3-3H]Putrescine dihydrochloride (60 Ci mmol−1) was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA), [3H(N)]spermidine trihydrochloride (19.1 Ci mmol−1) and [3H(N)]spermine trihydrochloride (16.6 Ci mmol−1) were bought from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA), and [1,5-14C] cadaverine dihydrochloride (15.8 mCi mmol−1) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Oligonucleotides were acquired from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA), except for ultamer oligonucleotides that were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). PfuUltra™ HF DNA ligase was procured from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA), and T4 DNA ligase and restriction endonucleases were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). The T. cruzi pTEX-GFP expression plasmid, a vector in which the GFP gene was ligated into the pTEX shuttle vector (Kelly et al., 1992), was generously provided by Dr Roberto Docampo (University of Georgia). Rabbit anti-mouse Oregon Green 488, goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 and tetramethyl-rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-concanavalin A conjugate were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO), and the rabbit polyclonal anti-calmodulin antisera were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA). All other reagents were of the highest grade commercially available.

Parasite cell culture

Epimastigotes of the T. cruzi genome project CL Brener reference strain (El-Sayed et al., 2005; http://tcruzidb.org/) were routinely grown at 28°C in either chemically undefined LIT medium (Castellani et al., 1967) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) or in SDM-79 supplemented with 10% FBS (Brun and Schonenberger, 1979) and 200 μM putrescine. T. cruzi can replicate indefinitely in SDM-79 with 10% FBS and 200 μM putrescine but can only proliferate in SDM-79 plus 10% FBS in the absence of putrescine for approximately 2 weeks. T. cruzi genomic DNA was prepared by standard protocols.

Cloning of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2

The TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 open reading frames were identified in the T. cruzi CL Brener genome sequence database (http://tcruzidb.org/tcruzidb/) using the Tblastn algorithm and the LmPOT1 primary structure (Hasne and Ullman, 2005) as the query sequence. Pairwise and multi-sequence alignments between TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 and orthologues were performed using the CLUSTAL W algorithm (Thompson et al., 1994), and transmembrane segments were predicted using the SOSUI (Hirokawa et al., 1998), DAS-TM segment (Cserzo et al., 1997) and HMMtop algorithms (Tusnady and Simon, 1998; 2001). Glycosylation sites were predicted using Motif Scan (Hulo et al., 2008) and DictyOGlyc (Gupta et al., 1999) web resources. The TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 open reading frames were amplified from T. cruzi genomic DNA with PfuUltra™ HF using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the amplified TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 products ligated into the pTEX-GFP vector, which attaches the GFP to the C-terminus of the polypeptide encoded by the foreign DNA insert. The sense and antisense oligonucleotides employed in the PCR amplification were 5′-GAAGGATCCATGAGTCCCGGTGGT-3′ and 5′-GCCAA GCTTGTTTGTGAAGCCCCG-3′ for TcPOT1.1 and 5′-GA AGGATCCATGAATCCCGGTGGT-3′ and 5′-CGCAAGCTTCGTGTGGGCATTTGC-3′ for TcPOT1.2 respectively (the BamHI and HindIII restriction sites are underlined, and the start codon in the sense primer is shown in boldface). The resultant plasmids were designated pTEX-TcPOT1.1::GFP and pTEX-TcPOT1.2::GFP. The HA epitope YPYDVPDYA from influenza virus A (HA tag) was also introduced by PCR at the NH2-terminus of both TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 using the following primer sets: 5′-GAAACTAGTGTTATG TACCCGTACGACGTGCCGGACTACGCGATGAGTCCCGGTGGTGAAT-3′ and 5′-GCCAAGCTTTTAGTTTGTGAAGCCCCGGCCTTCTCCATTTGGACGG-3′ for TcPOT1.1 and 5′-GAAACTAGTGTTATGTACCCGTACGACGTGCCGGACTACGCGATGAATCCCGGTGGTGAAT-3′ and 5′-GCCAAGCTTTTACGTGTGGGCATTTGCTTC-3′ for TcPOT1.2 (the SpeI and HindIII restriction sites are underlined, and the HA tag in the sense primer is in boldface). The amplified products were cloned into the pTEX vector and the resultant plasmids designated pTEX-HA::TcPOT1.1 and pTEX-HA::TcPOT1.2. Lastly, untagged versions of TcPOT1.1 and TcPOT1.2 were also created using the following primers: 5′-GAAACTAGTATGAGTCCCGGTGGTGAATCAAACTTTCAG-3′ and 5′-GCCAAGCTTTTAGTTTGTGAAGCCCCGGCCTTCTCCATTTGGACGG-3′ for TcPOT1.1 and 5′-GAAGGATCCATGAATCCCGGTGGT-3′ and 5′-GCCAAGCTTTTACGTGTGGGCATTTGCTTC-3′ for TcPOT1.2 (the restriction sites used in the ligations are underlined and the start codon is in boldface. The amplified products were cloned into the pTEX vector and the resultant plasmids designated pTEX-TcPOT1.1 and pTEX-TcPOT1.2.

As a control, the open reading frame to the T. cruzi paralogue (El-Sayed et al., 2005) to the GRASP (Barr et al., 1997), TcGRASP, was amplified by from T. cruzi genomic DNA by PCR and inserted into pTEX-GFP. Sense and antisense primers in the PCR amplifications of TcGRASP were 5′-ACTAGTATGGGACAGGAGGGGAGCAAG-3′ and 5′-GGATCCAGGCGTAGGTGTCGTTGGCCG-3′ (restriction sites are underlined and the start codon is in boldface) respectively. The resultant plasmid was designated pTEX-TcGRASP::GFP. The fidelity of all PCR-amplified sequences was confirmed by automated DNA sequencing.

T. cruzi transfections

Exponentially growing epimastigotes were transfected with 50–80 μg of T. cruzi genomic DNA in 21 mM HEPES, 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.7 mM Na2HPO4 and 6 mM glucose, pH 7.5 (HBS buffer) using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser electroporater set at 1500 V and 50 μF. After electroporation, cells were diluted into 5 ml of LIT medium, and transfectants were selected with Geneticin (G418) at a concentration that was gradually augmented from 50 to 200 μgml−1.

Transport assays

Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes in mid-log phase were harvested from mid-log cultures propagated in either LIT medium or SDM-79 medium plus 10% FBS and 200 μM putrescine and washed three times in PBS supplemented with 10 mM glucose (PBS-glucose). Uptake experiments were performed in Eppendorf tubes using a previously described rapid oil-stop technique (Hasne and Barrett, 2000). Briefly, 1 × 107 cells in 100 μl PBS-glucose were added to an equal volume of PBS-glucose containing radiolabelled ligand at various concentrations as indicated in the text and layered on top of a 100 μl of a chemically inert 1-bromododecane cushion. Exposure of parasites to ligand was terminated by centrifugation of the parasites through the 1-bromododecane layer. The cell pellets were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the radioactivity incorporated into the cells was quantified by liquid scintillation spectrometry using a Beckman LS6500 scintillation counter. The data were processed using the GraFit software package (Erithacus Software Limited, Horley, U.K.).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Trypanosoma cruzi transfectants expressing TcPOT1.1::GFP or TcPOT1.2::GFP were affixed to poly-l-lysine coverslips with 3.7% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and GFP fluorescence from the transporter construct measured after excitation at 488 nm and emission collection at 507 nm. Parasites expressing HA::TcPOT1.1 and HA::TcPOT1.2 were also attached to poly-l-lysine coverslips and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 30 min. Fixed parasites were washed three times with PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min and blocked for 30 min in 3% BSA/5% goat serum/50 mM NH4Cl in PBS. The parasites were then incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-HA primary antibody (1:2000) for 1 h, followed by an additional 1 h incubation with a goat anti-mouse Oregon Green 488 (1:1000). To envisage the parasite plasma membrane and flagellum, formaldehyde-fixed cells were treated for 5 min at room temperature with 5 μgml−1 TRITC-concanavalin A (Molecular Probes-Invitrogen) in PBS. TRITC fluorescence was detected after excitation at 544 nm and monitoring at 572 nm. Nuclear and kinetoplast DNA was stained with 500 ng ml−1 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). To visualize the parasite contractile vacuole, fixed and permeabilized parasites were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-calmodulin antibody (1:500) for 1 h followed by a second incubation with a goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 (1:1000) for 1 h. Cellular fluorescence was detected on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M deconvolution microscope, and images were captured on an AxioCam MRm camera and processed using Axiovision Release 4.6. software.

Immunoelectron microscopy

Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in 0.25 M HEPES, pH 7.4, for 1 h at room temperature and then in 8% paraformaldehyde in the same buffer overnight at 4°C. They were infiltrated, frozen and sectioned as described previously (Folsch et al., 2001). The sections were immunolabelled with mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibodies (1:500 in PBS/1% fish skin gelatin), then with anti-mouse IgG antibodies, and finally with 10 nm protein A-gold particles (Department of Cell Biology, Medical School, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands). Sections were examined with a CM120 electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, the Netherlands) under 80 kV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Grant AI41622 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and by a Grant-in-Aid #0950095G provided by the American Heart Association. We thank Kim Zichichi from the Yale Center for Cell and Molecular Imaging for excellent technical assistance with the immunoelectron microscopy. We also would like to thank Dr Roberto Docampo, Dr Wanderley de Souza and Dr Cynthia He for fruitful discussions on the immunoelectron microscopy data.

Footnotes

Supporting information Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Algranati ID, Sanchez C, Gonzalez NS. Polyamines in Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania mexicana. In: Goldemberg SH, Algranati ID, editors. The Biology and Chemistry of Polyamines. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1989. pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ariyanayagam MR, Fairlamb AH. Diamine auxotrophy may be a universal feature of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;84:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02788-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronow B, Kaur K, McCartan K, Ullman B. Two high affinity nucleoside transporters in Leishmania donovani. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987;22:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaraf YG, Golenser J, Spira DT, Messer G, Bachrach U. Cytostatic effect of DL-alpha-difluoromethylornithine against Plasmodium falciparum and its reversal by diamines and spermidine. Parasitol Res. 1987;73:313–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00531084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi CJ, McCann PP. Parasitic protozoa and polyamines. In: McCann PP, Pegg AE, Sjoerdsma A, editors. Inhibition of Polyamine Metabolism: Biological Significance and Basis for New Therapies. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1987. pp. 317–344. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi CJ, Nathan HC, Yarlett N, Goldberg B, McCann PP, Bitonti AJ, Sjoerdsma A. Cure of murine Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense infections with an S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2736–2740. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.12.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr FA, Puype M, Vandekerckhove J, Warren G. GRASP65, a protein involved in the stacking of Golgi cisternae. Cell. 1997;91:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard CB, Pye G, Steurer FJ, Rodriguez R, Campman R, Peterson AT, et al. Chagas disease in a domestic transmission cycle, southern Texas, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:103–105. doi: 10.3201/eid0901.020217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitonti AJ, Dumont JA, McCann PP. Characterization of Trypanosoma brucei brucei S-adenosyl-L-methionine decarboxylase and its inhibition by Berenil, pentamidine and methylglyoxal bis(guanylhydrazone) Biochem J. 1986;237:685–689. doi: 10.1042/bj2370685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitonti AJ, Byers TL, Bush TL, Casara PJ, Bacchi CJ, Clarkson AB, et al. Cure of Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense infections in mice with an irreversible inhibitor of S-504 adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1485–1490. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.8.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun R, Schonenberger M. Cultivation and in vitro cloning or procyclic culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei in a semi-defined medium. Short communication. Acta Trop. 1979;36:289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burri C, Brun R. Eflornithine for the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis. Parasitol Res. 2003;90(Suppl. 1):S49–S52. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0766-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo C, Cejas S, Gonzalez NS, Algranati ID. Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes lack ornithine decarboxylase but can express a foreign gene encoding this enzyme. FEBS Lett. 1999;454:192–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00804-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo C, Cejas S, Huber A, Gonzalez NS, Algranati ID. Lack of arginine decarboxylase in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2003;50:312–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo C, Serra MP, Pereira CA, Huber A, Gonzalez NS, Algranati ID. Heterologous expression of a plant arginine decarboxylase gene in Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1674:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo C, Canepa GE, Algranati ID, Pereira CA. Molecular and functional characterization of a spermidine transporter (TcPAT12) from Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:936–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani O, Ribeiro LV, Fernandes JF. Differentiation of Trypanosoma cruzi in culture. J Protozool. 1967;14:447–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1967.tb02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KP, Dwyer DM. Leishmania donovani. Hamster macrophage interactions in vitro: cell entry, intracellular survival, and multiplication of amastigotes. J Exp Med. 1978;147:515–530. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.2.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserzo M, Wallin E, Simon I, von Heijne G, Elofsson A. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 1997;10:673–676. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzin C, Marchal P, Casara P. Irreversible inhibition of rat S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase by 5′-([(Z)-4-amino-2-butenyl]methylamino)-5′-deoxyadenosine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:1499–1503. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90446-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo R, Moreno SN. Current chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis. Parasitol Res. 2003;90(Suppl. 1):S10–S13. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0752-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo R, de Souza W, Miranda K, Rohloff P, Moreno SN. Acidocalcisomes – conserved from bacteria to man. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:251–261. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed NM, Myler PJ, Bartholomeu DC, Nilsson D, Aggarwal G, Tran AN, et al. The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease. Science. 2005;309:409–415. doi: 10.1126/science.1112631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsch H, Pypaert M, Schu P, Mellman I. Distribution and function of AP-1 clathrin adaptor complexes in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:595–606. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas JM, Augusto-Pinto L, Pimenta JR, Bastos-Rodrigues L, Goncalves VF, Teixeira SM, et al. Ancestral genomes, sex, and the population structure of Trypanosoma cruzi. Plos Pathog. 2006;2:e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillin FD, Reiner DS, McCann PP. Inhibition of growth of Giardia lamblia by difluoromethylornithine, a specific inhibitor of polyamine biosynthesis. J Protozool. 1984;31:161–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1984.tb04308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez NS, Ceriani C, Algranati ID. Differential regulation of putrescine uptake in Trypanosoma cruzi and other trypanosomatids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;188:120–128. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)92358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez NS, Huber A, Algranati ID. Spermidine is essential for normal proliferation of trypanosomatid protozoa. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:323–326. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gull K. Host-parasite interactions and trypanosome morphogenesis: a flagellar pocketful of goodies. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:365–370. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Jung E, Gooley AA, Williams KL, Brunak S, Hansen J. Scanning the available Dictyostelium discoideum proteome for O-linked GlcNAc glycosylation sites using neural networks. Glycobiology. 1999;9:1009–1022. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.10.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ST, Hillier CJ, Gero AM. Crithidia luciliae: regulation of purine nucleoside transport by extracellular purine concentrations. Exp Parasitol. 1996;83:314–321. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasne MP, Barrett MP. Transport of methionine in Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;111:299–307. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasne MP, Ullman B. Identification and characterization of a polyamine permease from the protozoan parasite Leishmania major. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15188–15194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411331200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heby O, Persson L, Rentala M. Targeting the polyamine biosynthetic enzymes: a promising approach to therapy of African sleeping sickness, Chagas’ disease, and leishmaniasis. Amino Acids. 2007;33:359–366. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa T, Boon-Chieng S, Mitaku S. SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:378–379. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulo N, Bairoch A, Bulliard V, Cerutti L, Cuche BA, de Castro E, et al. The 20 years of PROSITE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D245–D249. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter KJ, Le Quesne SA, Fairlamb AH. Identification and biosynthesis of N1,N9-bis(glutathionyl)aminopropylcadaverine (homotrypanothione) in Trypanosoma cruzi. Eur J Biochem. 1994;226:1019–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.t01-1-01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Polyamine transport in bacteria and yeast. Biochem J. 1999;344(Part 3):633–642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Polyamines: mysterious modulators of cellular functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:559–564. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K, Ito K, Kashiwagi K. Polyamine uptake systems in Escherichia coli. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:271–278. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi K, Pistocchi R, Shibuya S, Sugiyama S, Morikawa K, Igarashi K. Spermidine-preferential uptake system in Escherichia coli. Identification of amino acids involved in polyamine binding in PotD protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12205–12208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi K, Shibuya S, Tomitori H, Kuraishi A, Igarashi K. Excretion and uptake of putrescine by the PotE protein in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6318–6323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi K, Kuraishi A, Tomitori H, Igarashi A, Nishimura K, Shirahata A, Igarashi K. Identification of the putrescine recognition site on polyamine transport protein PotE. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36007–36012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JM, Ward HM, Miles MA, Kendall G. A shuttle vector which facilitates the expression of transfected genes in Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3963–3969. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.15.3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierszenbaum F, Wirth JJ, McCann PP, Sjoerdsma A. Impairment of macrophage function by inhibitors of ornithine decarboxylase activity. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2461–2464. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.10.2461-2464.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinch LN, Scott JR, Ullman B, Phillips MA. Cloning and kinetic characterization of the Trypanosoma cruzi S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;101:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollien AH, Schaub GA. The development of Trypanosoma cruzi in triatominae. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01724-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Quesne SA, Fairlamb AH. Regulation of a high-affinity diamine transport system in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Biochem J. 1996;316(Part 2):481–486. doi: 10.1042/bj3160481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JC, Staehelin LA. A novel model for fluid secretion by the trypanosomatid contractile vacuole apparatus. J Cell Biol. 1979;83:371–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.83.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo AM, Oliveira RP, Pena SD. Chagas disease: role of parasite genetic variation in pathogenesis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2002;4:1–16. doi: 10.1017/S1462399402004118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo AM, Machado CR, Oliveira RP, Pena SD. Trypanosoma cruzi: genetic structure of populations and relevance of genetic variability to the pathogenesis of chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:1–12. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncayo A, Ortiz Yanine MI. An update on Chagas disease (human American trypanosomiasis) Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:663–677. doi: 10.1179/136485906X112248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay R, Kapoor P, Madhubala R. Characterization of alpha-difluoromethylornithine resistant Leishmania donovani and its susceptibility to other inhibitors of the polyamine biosynthetic pathway. Pharmacol Res. 1996;34:43–46. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1996.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda K, Esteva M, Segura EL, Bijovsy AT. The cytostome of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes is associated with the flagellar complex. Exp Parasitol. 1999;92:223–231. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg AE, McGovern KA, Wiest L. Decarboxylation of alpha-difluoromethylornithine by ornithine decarboxylase. Biochem J. 1987;241:305–307. doi: 10.1042/bj2410305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepin J, Milord F, Guern C, Schechter PJ. Difluoromethylornithine for arseno-resistant Trypanosoma brucei gambiense sleeping sickness. Lancet. 1987;2:1431–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson K, Aslund L, Grahn B, Hanke J, Heby O. Trypanosoma cruzi has not lost its S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase: characterization of the gene and the encoded enzyme. Biochem J. 1998;333:527–537. doi: 10.1042/bj3330527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reguera RM, Fouce RB, Cubria JC, Bujidos ML, Ordonez D. Fluorinated analogues of l-ornithine are powerful inhibitors of ornithine decarboxylase and cell growth of Leishmania infantum promastigotes. Life Sci. 1995;56:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00916-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohloff P, Docampo R. A contractile vacuole complex is involved in osmoregulation in Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohloff P, Montalvetti A, Docampo R. Acidocalcisomes and the contractile vacuole complex are involved in osmoregulation in Trypanosoma cruzi. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52270–52281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez CP, Mucci J, Gonzalez NS, Ochoa A, Zakin MM, Algranati ID. Alpha-difluoromethylornithine-resistant cell lines obtained after one-step selection of Leishmania mexicana promastigote cultures. Biochem J. 1997;324:847–853. doi: 10.1042/bj3240847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz de Tarlovsky MN, Hernandez SM, Bedoya AM, Lammel EM, Isola EL. Polyamines in Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1993;30:547–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfang A, Landfear SM. Substrate depletion upregulates uptake of myo-inositol, glucose and adenosine in Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;104:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachihara K, Uemura T, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. Excretion of putrescine and spermidine by the protein encoded by YKL174c (TPO5) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12637–12642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira AR, Nitz N, Guimaro MC, Gomes C, Santos-Buch CA. Chagas disease. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:788–798. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.047357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomitori H, Kashiwagi K, Asakawa T, Kakinuma Y, Michael AJ, Igarashi K. Multiple polyamine transport systems on the vacuolar membrane in yeast. Biochem J. 2001;353:681–688. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusnady GE, Simon I. Principles governing amino acid composition of integral membrane proteins: application to topology prediction. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:489–506. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusnady GE, Simon I. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:849–850. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura T, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. Polyamine uptake by DUR3 and SAM3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7733–7741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nieuwenhove S, Schechter PJ, Declercq J, Bone G, Burke J, Sjoerdsma A. Treatment of gambiense sleeping sickness in the Sudan with oral DFMO (DL-alpha-difluoromethylornithine), an inhibitor of ornithine decarboxylase; first field trial. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79:692–698. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatarunakamura C, Ueda-Nakamura T, de Souza W. Visualization of the cytostome in Trypanosoma cruzi by high resolution field emission scanning electron microscopy using secondary and backscattered electron imaging. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;242:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert EK, Phillips MA. Cross-species activation of trypanosome S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase by the regulatory subunit prozyme. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;168:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.