Abstract

Background

Patients with scleroderma interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) are thought to have the greatest decline in lung function (forced vital capacity % predicted [FVC%]) in the early years after onset of systemic sclerosis (SSc). We assessed the natural history of FVC% decline in patients receiving placebo in the Scleroderma Lung Study and evaluated possible factors for cohort enrichment for future therapeutic trials.

Methods

Patients randomized to placebo (N=79) were divided into 3 groups based on SSc disease duration (0–2, 2–4 and >4 years). Descriptive statistics and a mixed effect model were used to analyze the rate of decline of FVC% over a 1-year period. We performed additional analyses stratified by severity of fibrosis on HRCT and explored interactions of severity and disease duration.

Results

The mean (SD) decline in the unadjusted FVC% during the 12-month period was 4.2 (12.8)%. At baseline, 28.5%, 43.0% and 28.5% of patients were in 0–2, 2–4 and >4 years disease groups, respectively. Rate of decline in FVC% was not significantly different across the 3 disease groups (P=0.85). When stratified by baseline fibrosis on HRCT, rate of decline of FVC% was statistically greater in the severe fibrosis group (annualized decline in FVC% in the severe group=7.2 vs. 2.7, p=0.008). The decline in the severe fibrosis group was most pronounced in those with relatively short disease duration (0–2 years, annualized decline= 7.0%).

Conclusion

Patients with SSc-ILD in the Scleroderma Lung Study had similar rates of progression of lung disease irrespective of disease duration. Baseline HRCT fibrosis score is a predictor of future FVC% decline in the absence of effective treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary disease is the leading cause of hospitalization and mortality in systemic sclerosis (SSc)(1). Approximately 40% of patients with SSc develop moderate to severe restrictive lung disease(2). Longitudinal cohorts have provided important information on natural history of lung disease in SSc. Most of the decline in pulmonary function occurs during the first 3–4 years after the onset of non-Raynaud’s SSc symptoms(2;3) and the pulmonary course is indolent after that. However, there is intra-individual variability in the changes in pulmonary physiological tests over time in patients with SSc. In addition, recent data suggest that the presence of moderate-to-severe fibrosis at baseline predicts poor survival in patients with SSc-ILD(4).

Results from the recently concluded Scleroderma Lung Study (SLS)(5), a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial, showed that daily oral cyclophosphamide (CYC) for 12 months is better than placebo in stabilizing lung function as measured by the forced vital capacity percent predicted (FVC% predicted) and improving health-related quality of life(6;7) in SSc-ILD during the treatment period. This large study recruited 158 patients with SSc-ILD, of whom 79 received placebo for a period of 1 year. Based on previous studies(2;8), the SLS-I hypothesized a 9% annualized decline in FVC% predicted(5). However, the study noted a decline of 2.6% over a 1 year treatment period in the patients assigned to placebo. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the variables associated with a greater decline in FVC % predicted since such characteristics could be useful for cohort enrichment in future therapeutic trials in SSc-ILD.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were participants in the SLS who were considered to have SSc-ILD as defined by neutrophilia of ≥ 3% and/or ≥ 2% eosinophilia in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and/or any ground glass opacity on HRCT. Subjects also had to have had the onset of the first non-Raynaud’s symptom or sign of SSc <7 yrs prior to entry (based on data from Steen et al(2)), FVC between 45% and 85% of the predicted value and at least grade 2 dyspnea score on the Mahler Baseline Dyspnea Index (e.g., shortness of breath when climbing ≥2 flight of stairs)(9). Further details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described previously (5).

Pulmonary Function Tests

Baseline measures of forced vital capacity (FVC), total lung capacity (TLC) and single-breath diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) were obtained at study entry and every 3 months for the duration of the study. Pulmonary function tests were performed on study-certified equipment in accordance with recommended standards(10;11) and the quality of the tests was carefully monitored by centralized over-reading, as previously described(5). All spirometric and DLCO procedures had to be carried out on equipment that met the performance standards of the American Thoracic Society. All tests were carried out in University-based pulmonary function laboratories, all of which were site visited by the Director of the Pulmonary Function Quality Control Core for SLS I (DPT). Moreover, as part of the overall pulmonary function quality control process, print-outs of calibration curves and of all numerical and graphic results were submitted on a regular basis to the Pulmonary Function Quality Control Core for quality assessment. The overall quality of the test results, while varying somewhat from site to site in this 13-center study, was judged to range from satisfactory to excellent.

High Resolution Chest Tomography

High resolution CT scans were obtained in the prone position, without contrast, from the lung apices to bases(12). Two independent radiologists who were blinded to the treatment assignment (CYC or placebo for 12 months) carried out the scoring based on semi-quantitative visual assessment. Lung images were divided into three zones for each lung. The upper lung zone extended from the lung apices to the aortic arch, the middle lung zone consisted of the area from the aortic arch to the inferior pulmonary veins, and the lower lung zone was assigned to the area from the inferior pulmonary veins to the diaphragm. Each of the six zones (except for 20 subjects who were not scanned in the upper lung zone) from the right and left lungs was scored for ground glass opacification (opacity through which normal lung markings could be seen), fibrosis (reticular opacity, traction bronchiectasis and/or bronchiolectasis) and honeycomb cysts(13). Because SSc-ILD predominantly affects the lower lung zones we believe that an average score across all lung zones would dilute the effect of the most severely affected zones. Therefore, we used the score from the zone with the worst extent of abnormality (maximum score) in our analyses. In all patients (except for 1), the maximum fibrosis score at baseline was represented by the lower lung zones. Therefore, while the lung apices were not scanned in 14% of the subjects, we believe it unlikely that we missed zones with the true maximum score in these patients. Scores for each lung zone comprised the following: 0 - absence of any pulmonary abnormality; 1 - 1–25% extent of involvement, 2 - 26–50%, 3- 51–75% and 4 - 76–100% extent of involvement.

Autoantibodies

Autoantibody data were available in 55 patients and included anti-SCL-70, anti-RNA polymerase III and anti-centromere antibodies which were performed by ELISA assays from Alpco Diagnostics (Scl-70 and anti-Centromere) and MBL International (anti-RNA Polymerase III).

Statistical Analysis

Based on the previous analysis by Steen and colleagues(2), we divided the placebo subjects into 3 groups based on the duration of SSc prior to study entry: 0–2 years (Group A); 2–4 years (Group B) and more than 4 years (Group C). Disease duration was defined as the duration from the onset of first non-Raynaud’s sign or symptom attributed to SSc as determined by direct interview of participating subjects during screening and was captured in the case report form. The outcomes of interest were the annual rates of decline in FVC% and DLCO%. Due to baseline differences in physiological measures in the 3 disease duration groups, the outcomes were examined as the change in FVC% or DLCO% over the 1 year period divided by the baseline FVC% or DLCO%. Because our goal was to evaluate variables associated with greater decline in FVC% for cohort enrichment in future therapeutic trials, we examined the influence on the observed rate of decline in subjects assigned to placebo of pre-specified variables that have previously been found to be associated with decline in FVC% or mortality in SLS-I and other cohorts(4). Summary statistics were generated for baseline demographic and clinical data among the 3 disease-duration groups; analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables among the 3 groups, and Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Two-year data were not included due to discontinuations during the second year.

We used a linear mixed effects model to evaluate the association between the outcome variables (rate of decline in FVC% and DLCO%) and covariates with a random intercept to account for within-subject correlation of the outcome variables across multiple visits. First, we generated 3 models to assess the associations between maximum HRCT fibrosis, ground glass, and honeycombing scores at baseline on the rates of decline in FVC and DLCO % predicted, including variables of time, disease duration and interactions among time, disease duration and HRCT scores. If there was a significant association, we used linear mixed effects models to assess the relationships between primary outcome measures (rate of decline in FVC % and DLCO % predicted) and the following covariates—disease duration, maximum HRCT scores at baseline (fibrosis, honeycombing, ground glass opacity), age, gender, baseline dyspnea index (BDI) scores, autoantibody status (anti-SCL-70 vs. anti-RNA Polymerase III vs. and anti-centromere and others), smoking status, and modified Rodnan skin score. We also performed sensitivity analyses after reclassifying disease duration by including Raynaud’s phenomenon in the definition of the first SSc sign or symptom.

All analyses were performed using SAS software; p< 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Since this was an exploratory analysis, we did not account for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Seventy-nine of 158 eligible patients were randomly assigned to placebo; 77 had known baseline disease duration and were included in this analysis. Of these, 66 completed the 12-month study visit; 55 of these 66 patients completed all clinic visits and the remaining 11 had withdrawn from randomized treatment or had been considered a treatment failure at some time during the treatment year but returned to complete the 12-month study visit. At baseline, there were 22 (28.5%) patients in Group A, 33 (43.0%) patients in Group B and 22 (28.5%) patients in Group C. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the placebo patients according to the 3 categories of disease duration. Patients in Group A were significantly older at baseline compared to the other 2 groups (mean age= 56.2 years for Group A vs. 46.4 and 43.4 years for Groups B and C, respectively), there was a trend toward a higher proportion of females in Group C, and the Mahler BDI total scores were significantly higher in Group A than in Groups B and C. Autoantibody data were available in 55 patients. Of these, 19 (35%) had anti-SCL-70 positivity, 5 (9%) were positive for anti-RNA polymerase III and anti-centromere antibodies, and 31 (56%) had other antibodies that were not characterized (Table 1). Patients in Group A had slightly lower baseline FVC and DLCO % predicted values compared to other 2 groups but these differences were not statistical different (p=0.6 for both FVC% and DLCO%). No significant differences in health-related quality of life measures or in HRCT disease extent were noted across the 3 groups.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics, stratified by disease duration (defined from 1st non-Raynaud sign or symptom)

| Variables | All Patients (N=77) | Group A (N=22) Disease dur 0–2 years |

Group B (N=33) Disease dur 2–4 years |

Group C (N=22) Disease dur >4 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, Mean (SD)* | 48.3 (12.5) | 56.2 (12.4) | 46.4 (11.9) | 43.4 (10.1) |

| Female, N (%) | 48.0 (62.3) | 12.0 (54.6) | 18.0 (54.6) | 18.0 (81.8) |

| Race, N (%) | ||||

| White | 51.0 (66.2) | 15.0 (68.2) | 22.0 (66.7) | 14.0 (63.6) |

| Type of SSc, N (%) | ||||

| Limited | 32 (41.6) | 8.0 (36.4) | 16.0 (48.5) | 8.0 (36.4) |

| Diffuse | 45.0 (58.4) | 14.0 (63.6) | 17.0 (51.5) | 14.0 (63.6) |

| Disease duration, yrs, Mean (SD)* | 3.2 (1.9) | 1.1 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.6) | 5.7 (0.7) |

| Antibodies (N=55), N (%)* | ||||

| SCL-70 | 19 (35) | 1(8) | 7(28) | 11(65) |

| anti-RNA Polymerase III/anti-centromere | 5 (9) | 0(0) | 4(16) | 1(6) |

| Others | 31(56) | 12(92) | 14(56) | 5(29) |

| FVC, %predicted, Mean (SD) | 68.19 (12.9) | 65.5 (13.4) | 68.2 (13.9) | 70.8 (10.7) |

| DLco, %predicted, Mean (SD) | 46.8 (13.9) | 44.9 (13.9) | 46.1 (12.9) | 49.8 (15.6) |

| MRSS, Mean (SD) | 14.2 (10.8) | 16.8 (12.1) | 13.3 (10.5) | 12.9 (9.1) |

| Mahler’s BDI focal score (0–12), Mean(SD)* | 5.7 (1.9) | 6.8 (2.1) | 5.2 (1.8) | 5.4 (1.8) |

| HAQ-DI (0–3), Mean (SD) | 0.70 (0.70) | 0.9 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.6) |

| SF-36 PCS (0-00), Mean (SD) | 34.5 (10.8) | 30.4 (11.9) | 35.5 (9.8) | 37.0 (10.5) |

| SF-36 MCS (0-00), Mean (SD) | 50.8 (10.5) | 48.3 (10.7) | 52.9 (8.5) | 50.2 (12.9) |

| HRCT disease extent, Mean (SD) | ||||

| Max Fibrosis Score (0–4) | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.0) |

| Max Honeycombing (0–4) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.5) |

| Max Ground Glass Opacity (0–4) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.6) |

p< 0.05

Rate of decline in FVC and DLCO % predicted, stratified by disease duration groups

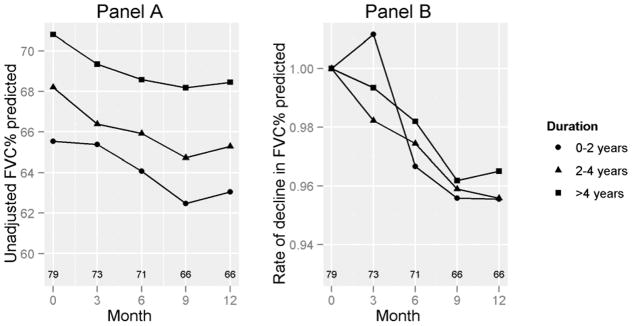

For all groups considered together, mean (SD) decline in the unadjusted FVC% predicted was −4.2 (12.8)% and mean (SD) decline in the unadjusted DLCO% predicted was −8.2 (18.6)%. Change in FVC% predicted over 12 months was not correlated with baseline % FVC predicted (r −0.08, p = 0.54). No significant differences in the rate of decline of FVC % predicted were observed across the 3 groups (Figure 1a and Table 2; p=0.85). No between-group differences were noted in the rate of decline in adjusted FVC % predicted for baseline FVC % predicted (Figure 1b; p=0.6). For DLCO%, Group A had a greater mean decline (17.9 [26.3] %) over 12 months compared to the other 2 groups (P=0.03; Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Decline in FVC% predicted, by disease duration.

Panel A shows the decline in % FVC over a period of 12 months. Panel B shows the rate of decline in FVC % predicted, adjusted for the baseline FVC % predicted. Numbers above the X-axis represent numbers of subjects corresponding to the data points at the corresponding months. P=NS

Table 2.

Decline in FVC% in placebo group over 12 months

| N | Decline in FVC% predicted, Mean (SD) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease duration, years | |||

| 0–2 | 17 | 4.4 (18.8) | 0.85 |

| 2–4 | 29 | 4.4 (10.1) | |

| >4 | 18 | 3.5 (10.1) | |

|

| |||

| HRCT Fibrosis score | |||

| 0–2 | 40 | 2.7 (12.8) | 0.008 |

| 3–4 | 25 | 7.2 (11.8) | |

|

| |||

| HRCT Ground Glass Opacity score | |||

| 0–1 | 55 | 4.9(13.0) | 0.61 |

| 2–3 | 10 | 1.8 (9.8) | |

|

| |||

| HRCT Honeycombing | |||

| 0 | 38 | 3.8 (14.5) | 0.96 |

| ≥1 | 27 | 5.3 (9.2) | |

|

| |||

| Autoantibodies | |||

| SCL-70 | 17 | 5.2 (9.1) | 0.88 |

| Anti-Polymerase-III/anti-centromere | 5 | 6.9 (11.5) | |

| Others | 26 | 4.4 (11.8) | |

|

| |||

| Overall | 66 | 4.2(12.8) | |

Rate of decline in FVC and DLCO% predicted, stratified by maximum HRCT scores at baseline

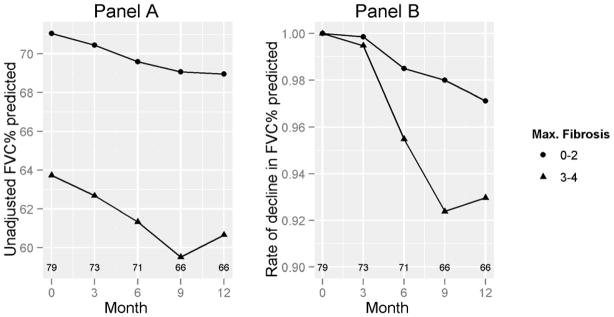

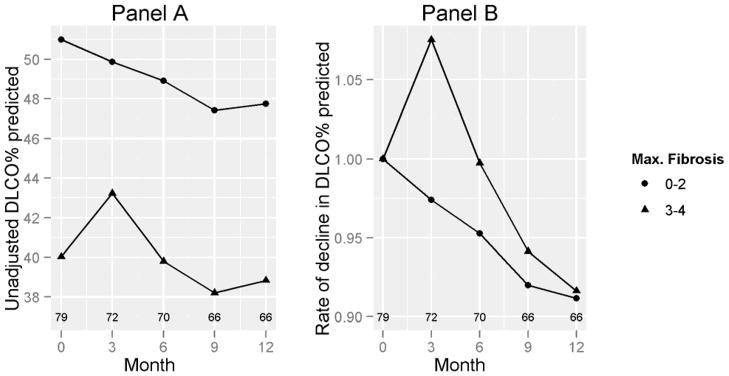

We further explored the impact of maximum HRCT scores for fibrosis, ground glass opacity, and honeycombing at baseline on rate of decline in FVC% and DLCO%. The cut-off HRCT values for comparison were based on the distribution of the baseline HRCT variables. No difference was seen in the rate of decline in patients who were stratified by different degrees of severity of ground glass opacity or honeycombing (P=NS, Table 2). On the other hand, when we divided patients based on their maximum HRCT fibrosis score of none to moderate fibrosis (score 0–2) vs. severe to very severe fibrosis (score 3–4), patients with severe fibrosis (score 3–4) showed a greater mean (SD) decline in FVC% (7.2 [11.8]%) compared to the groups with none-to-moderate fibrosis (2.7 [12.8],%; p = 0.008) (Table 2; Figure 2). On the other hand, the differences in declines in DLCO% predicted between those with a fibrosis score of 3–4 vs. 0–2 were not significant (8.8 [21.6]% vs. 8.3 [16.7]%), respectively; p = 0.22) (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. FVC% by baseline HRCT-maximum fibrosis score.

Panel A shows the decline in % FVC, stratified by maximum HRCT fibrosis at baseline. Panel B shows the rate of decline in FVC % predicted adjusted for the baseline FVC % predicted. Numbers above the X-axis represent numbers of subjects corresponding to the data points. P=0.008

Figure 3. DLCO% by baseline HRCT-maximum fibrosis score.

Panel A shows the decline in % DLCO, stratified by maximum HRCT fibrosis at baseline. Panel B shows the rate of decline in DLCO % predicted adjusted for the baseline DLCO % predicted. Numbers above the X-axis represent numbers of subjects corresponding to the data points. P=NS

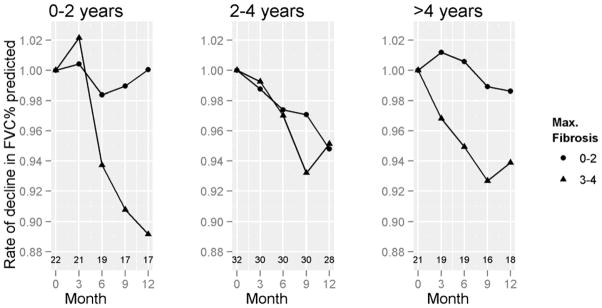

We further assessed the impact of disease duration on the decline in FVC% by HRCT fibrosis category. Patients in Group A with HRCT fibrosis scores of ≥ 3 ((7.04[8.70%]) had a greater decline in their FVC% compared to Group A patients with HRCT fibrosis of 0–2 (0.94[12.24%]) (p=0.03). On the other hand, no significant differences in the rate of decline of FVC % were observed between the different HRCT maximum fibrosis groups within the other two categories of disease duration (i.e., 2–4 or >4 years) (Figure 4). In the linear mixed model, the presence of HRCT fibrosis of ≥ 3 was associated with a significant decline in FVC% predicted (p=0.004) after adjusting for covariates (Supplementary Table 2). The models that included different degrees of GGO and honeycombing did not show any significant association with decline in FVC% predicted irrespective of disease duration.

Figure 4. FVC% by Baseline Maximum HRCT-Fibrosis, by disease duration.

Figure shows the rate of decline in FVC % predicted, adjusted for the baseline FVC % predicted for Groups A, B, and C. Numbers above the X-axis represent numbers of subjects corresponding to the data points at the corresponding months. P=0.03 for 0–2 years, NS for 2–4 years, & NS for > 4 years.

We further assessed the interaction between HRCT-fibrosis score and 3 disease duration groups. Patients in Group A had a significant interaction between fibrosis (≥ 3) and month (p=0.03), demonstrating that patients with HRCT-fibrosis score ≥ 3 and early disease duration had an increased decline in FVC% predicted over 12 months compared to those with lesser degrees of fibrosis. The annualized rate of decline was 7.0% in Group A with HRCT-fibrosis score ≥ 3 compared to 0.9% with HRCT-fibrosis score < 3. This interaction between fibrosis and month of treatment was not significant for other disease durations. No association was noted between HRCT scores (fibrosis, GGO and honeycombing) and DLCO% predicted for any diseases duration category. We reclassified disease duration by including Raynaud’s phenomenon in the definition of the first SSc sign or symptom. The median (25th–75th) disease duration was 1.6 (1.2–1.9) years for Group A, 2.5 (2.5–4.4) years for Group B, and 6.7 (5.5, 8.2) years for Group C. When the disease duration was reclassified by using Raynaud’s phenomenon to determine the onset of SSc disease, no differences were noted compared to using the date of first non-Raynaud’s sign or symptom.

Rate of decline in FVC and DLCO% predicted, stratified by autoantibodies

The rates of decline in FVC% and DLCO% predicted were similar in patients with anti- SCL70 vs. other autoantibodies (p values=0.70 and 0.88, respectively; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

SLS was the first randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) in patients with SSc-ILD to demonstrate the efficacy of a pharmacologic intervention for this disease (5). Since daily oral cyclophosphamide (CYC) affected the change in FVC % predicted over the year of therapy, the placebo group was selected for analysis to avoid confounding by active treatment. The placebo group enrolled a large number of patients, providing a unique opportunity to assess the natural history of SSc-ILD over the period of 1 year. In our current analysis, we show that the placebo group had a decline in unadjusted FVC% (4.2%) and DLCO% (8.2%) over a period of 12-months. The unadjusted rates of decline in FVC% and DLCO% were similar across the categories of disease duration (0–2, 2–4, and >4 years). A greater extent of maximum fibrosis on HRCT at baseline was associated with a greater decline in FVC % predicted and this effect on FVC % predicted was most evident during 0–2 years after disease onset. The reason why a greater extent of fibrosis at baseline predisposes to a greater rate of decline in a physiologic indicator of disease severity in patients with evidence of interstitial lung disease is not clear. A possible explanation for these findings may be that a greater extent of fibrosis at baseline in such patients might represent a more rapid progression of inflammation to lung fibrosis prior to study entry that continues during the ensuing year, as reflected by a greater rate of decline in FVC % predicted over this time interval.

Previous published data on the decline in lung function comes from a large observational cohort at the University of Pittsburgh. Steen et al(2) demonstrated that the major loss of FVC% occurred within the first 4–6 years of SSc; patients who developed severe restrictive disease (FVC ≤ 50% of predicted) had lost 32% of their remaining FVC each year for the first 2 years, 12% of remaining FVC for each of the next 2 years, and 3% of remaining FVC for each of the following 2 years. In another observational study from Greece, Plastiras and colleagues retrospectively analyzed patients with SSc(3) and found that baseline FVC% predicted values measured in 60 patients within the first 3 years from disease onset predicted the subsequent rate of change in pulmonary function. Neither Steen et al. (2) nor Plastiras et al. (3) performed HRCT or bronchoalveolar lavage in their cohorts. In a non-randomized treatment study of patients with SSc-ILD and evidence of alveolitis on BAL, White et al (8) retrospectively compared their patients who were treated with oral CYC versus those who refused therapy. Oral CYC was given for a median of 10.8 months and the investigators noted a 4.3% improvement in FVC% predicted (compared to a 7.1% decline in those who refused treatment with CYC) (8). Based on results of the 2 observational studies and the study of White and colleagues (8), SLS-I was designed to capture patients with both relatively early disease duration (defined as <7 years from 1st non-Raynaud’s sign or symptom) and evidence of presumed active interstitial lung disease (defined by BAL and/or HRCT) with the assumption that these patients would have a greater decline in their FVC% over a period of 1-year. However, in SLS-1 the rate of decline in FVC % predicted was only 4.2 % over a 12-month period and did not vary across the 3 disease duration groups. We suspect that the lack of any demonstrable effect of disease duration on rate of decline in our subject population might be due to inherent differences in patients enrolled in a randomized controlled trial vs. patients followed in observational studies. It is likely that patients with moderate-to-severe disease with rapidly declining lung physiology were likely underrepresented in the SLS; patients with less extensive disease may be selectively enrolled in a placebo-controlled study, while those with more aggressive disease may be overrepresented in pilot reports of open treatments.

Previous analyses of data from SLS-I (which included both CYC and placebo groups) (5) and Goh et al (4) have found that moderate to severe fibrosis on the baseline HRCT scan is an independent predictor of response to CYC and poor survival, respectively. Results of our current analysis support previous analyses that moderate to severe maximum fibrosis on baseline HRCT (defined as ≥ 50% extent of fibrosis in the lung zone with the maximum fibrosis score) is also an independent predictor of decline in FVC% predicted (Table 2, p=0.008). On the other hand, the baseline ground glass appearance and honeycombing were not predictors of decline in FVC% predicted. One of the inclusion criteria for the SLS was the presence of any ground glass appearance on HRCT with the notion that ground glass opacification on HRCT represents reversible inflammation. Work on the validity of HRCT has been done with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In one study, the correlation of “ground-glass opacification” on HRCT with “inflammation” on lung specimens was weak (r=0.27)(14). In another recent study(15), a normal HRCT had a good association with normal pathology on lung specimens (r=0.72). However, there was no association of ground-glass opacification with any histology pattern (r values <0.20); it has been suggested that ground glass on CT may represent fine (subresolution) fibrosis rather than reversible inflammation(16).

Our results have implications for future therapeutic trial designs in SSc-ILD. Cohort enrichment can be attained by recruiting patients with a moderate-to-severe degree of baseline fibrosis on HRCT in the zone(s) with greatest fibrosis. These findings complement those obtained in 215 SSc patients followed for 10 years (4) in whom the baseline FVC% and HRCTs were predictive of mortality risk. Also, based on recent studies showing a negative association between BAL and FVC% predicted(4;17), bronchoalveolar lavage cellularity is likely not be utilized as an inclusion criterion in future RCTs. On the other hand, HRCT is likely to be included in future SSc-ILD RCTs(12;13) for i) cohort enrichment based on extent of disease and ii) adjustment for baseline severity in key treatment effect analyses (since it is likely that a treatment effect may differ in cases with mild rather than extensive lung disease). In addition, serial HRCT can provide a surrogate end point or more accurate measure of serial change in pulmonary fibrosis. Moreover, baseline HRCT is important in the determination of patient eligibility for excluding other significant thoracic disease not attributable to SSc (18).

A major limitation of the current study was that only 55 of the 77 patients completed the first 12 months of the trial. However, the present analysis of the natural history of SLS-ILD is based on the largest sample of patients with this disease examined to date. Second, this analysis is restricted to patients participating in a RCT and not necessarily applicable to patients in general clinical practice. Third, SSc-ILD trial designs continue to evolve(18) and the results of this analysis may not be applicable to other SSc-ILD studies with different inclusion/exclusion criteria. Lastly, our analysis is limited to a 1 year duration. However, the current recommendations(18) propose a trial design for a minimum of 1 year and our 1-year data may inform the the design of future trials. In conclusion, we present the natural course of SSc-ILD over a period of 1 year. Future SSc-ILD clinical trials can achieve cohort enrichment by enrolling patients with moderate-to-severe fibrosis on HRCT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: SLS was funded by NIH/NHLBI Grant PHS grant no. UO1 HL605.

Dr. Khanna was supported by a National Institutes of Health Award (NIAMS K23 AR053858-04) and the Scleroderma Foundation (New Investigator Award).

Reference List

- 1.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steen VD, Conte C, Owens GR, Medsger TA., Jr Severe restrictive lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(9):1283–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plastiras SC, Karadimitrakis SP, Ziakas PD, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Moutsopoulos HM, Tzelepis GE. Scleroderma lung: initial forced vital capacity as predictor of pulmonary function decline. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(4):598–602. doi: 10.1002/art.22099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goh NS, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(11):1248–54. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(25):2655–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna D, Yan X, Tashkin DP, Furst DE, Elashoff R, Roth MD, et al. Impact of oral cyclophosphamide on health-related quality of life in patients with active scleroderma lung disease: results from the scleroderma lung study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1676–84. doi: 10.1002/art.22580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna D, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Chon Y, Elashoff R, Roth MD, et al. Correlation of the degree of dyspnea with health-related quality of life, functional abilities, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide in patients with systemic sclerosis and active alveolitis: results from the Scleroderma Lung Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(2):592–600. doi: 10.1002/art.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White B, Moore WC, Wigley FM, Xiao HQ, Wise RA. Cyclophosphamide is associated with pulmonary function and survival benefit in patients with scleroderma and alveolitis. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(12):947–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-12-200006200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna D, Tseng CH, Furst DE, Clements PJ, Elashoff R, Roth M, et al. Minimally important differences in the Mahler’s Transition Dyspnoea Index in a large randomized controlled trial--results from the Scleroderma Lung Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacIntyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, Johnson DC, van der Grinten CP, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(4):720–35. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, Pedersen OF, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(3):511–22. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldin J, Elashoff R, Kim HJ, Yan X, Lynch D, Strollo D, et al. Treatment of scleroderma-interstitial lung disease with cyclophosphamide is associated with less progressive fibrosis on serial thoracic high-resolution CT scan than placebo: findings from the scleroderma lung study. Chest. 2009;136(5):1333–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldin JG, Lynch DA, Strollo DC, Suh RD, Schraufnagel DE, Clements PJ, et al. High-resolution CT scan findings in patients with symptomatic scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2008;134(2):358–67. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kazerooni EA, Martinez FJ, Flint A, Jamadar DA, Gross BH, Spizarny DL, et al. Thin-section CT obtained at 10-mm increments versus limited three-level thin-section CT for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: correlation with pathologic scoring. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169(4):977–83. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schettino IA, Ab’Saber AM, Vollmer R, Saldiva PH, Carvalho CR, Kairalla RA, et al. Accuracy of high resolution CT in assessing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis histology by objective morphometric index. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198(5):347–54. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antoniou KM, Wells AU. Scleroderma lung disease: evolving understanding in light of newer studies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20(6):686–91. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283126985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strange C, Bolster MB, Roth MD, Silver RM, Theodore A, Goldin J, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage and response to cyclophosphamide in scleroderma interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):91–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200705-655OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna D, Brown KK, Clements PJ, Elashoff R, Furst DE, Goldin J, et al. Systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease-proposed recommendations for future randomized clinical trials. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(2 Suppl 58):S55–S62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.