Abstract

The linear tetracyclic TAN-1612 (1) and BMS-192548 (2) were isolated from different filamentous fungal strains, and have been examined as potential neuropeptide Y and neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist respectively. Although the biosynthesis of fungal aromatic polyketides has attracted much interest in recent years, the biosynthetic mechanism for such naphthacenedione-containing products has not been established. Using a targeted genome mining approach, we first located the ada gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of 1 in Aspergillus niger ATCC 1015. The connection between 1 and the ada pathway was verified through overexpression of the Zn2Cys6-type pathway-specific transcriptional regulator AdaR and subsequent gene expression analysis. The enzymes encoded in the ada gene cluster share high sequence similarities to the known apt pathway linked to the biosynthesis of anthraquinone asperthecin 3. Subsequent comparative investigation of these two highly homologous gene clusters by heterologous pathway reconstitution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed a novel α-hydroxylation-dependent Claisen cyclization cascade, which involves a flavin-dependent monooxygenase (FMO) that hydroxylates the α-carbon of an ACP-bound polyketide and a bifunctional metallo-β-lactamase-type thioesterase (MβL-TE). The bifunctional MβL-TE catalyzes the fourth ring cyclization to afford the naphthacenedione scaffold upon α-hydroxylation, while performs hydrolytic release of an anthracenone product in the absence of α-hydroxylation. Through in vitro biochemical characterizations and metal analyses, we verified that the apt MβL-TE is a dimanganese enzyme and requires both Mn2+ cations for the observed activities. The MβL-TE is the first example of TE in polyketide biosynthesis that catalyzes the Claisen-like condensation without an α/β hydrolase fold and forms no covalent bond with the substrate. These mechanistic features should be general to the biosynthesis of tetracyclic naphthacenedione compounds in fungi.

INTRODUCTION

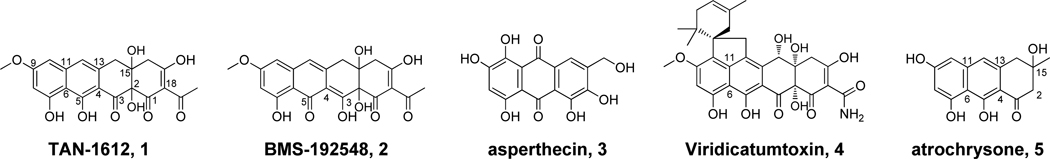

Polycyclic aromatic polyketides constitute an important family of natural products and exhibit a broad range of beneficial and deleterious bioactivities, including anticancer (e.g. doxorubicin), antibacterial (e.g. tetracycline), antifungal (e.g. griseofulvin), antiparasitic (e.g. frenolicin) and carcinogenic (e.g. aflatoxin)1 activities. They are synthesized by polyketide synthases (PKSs) from acetate building blocks followed by regioselective cyclizations of the highly reactive poly-β-ketone backbones into different polycyclic ring systems.2 Filamentous fungi, like the actinomycetes bacteria, are prolific producers of aromatic polyketides. Fungi use non-reducing polyketide synthases (NRPKSs) to synthesize a diverse array of polycyclic compounds,3 such as the anthraquinone norsolorinic acid that is the precursor of aflatoxin,4 the spirobenzofuranone-containing griseofulvin,5 the naphtho-γ-pyrone YWA1,6 and the anhydrotetracycline-like naphthacenedione viridicatumtoxin (vrt)7 4 (Scheme 1). The mechanisms of polyketide chain length control and regioselective cyclization in fungal PKSs are significantly different from the well-studied bacterial type II PKSs, are less understood, and are therefore of significant biochemical interests.8

Scheme 1.

Anthracenone and Naphthacenedione natural products isolated from fungi.

Each NRPKS is an iterative type I megasynthase that contains catalytic domains arranged in a linear fashion.3 The core domains, juxtaposed from the N- to C-terminus, consist of a starter unit:ACP transacylase (SAT),9 a ketosynthase (KS), a malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase (MAT), a product template (PT) domain4,10 and an acyl-carrier protein (ACP)11. Other domains, such as methyltransferase (MeT)12 and chain-releasing thioesterase/Claisen cyclase (TE/CLC)13 or reductase (R)14 can also be found in some NRPKSs. NRPKSs utilize PT domains to control the cyclization regioselectivity of poly-β- ketone backbones synthesized by the minimal PKS domains (KS, MAT and ACP).4,10a The PT domains of most NRPKSs can be classified phylogenetically into five major groups with each group corresponding to a unique first-ring cyclization regioselectivity and/or product size: Group I, C2-C7 and monocyclic; Group II, C2-C7 and bicyclic; Group III, C2-C7 and multicyclic; Group IV, C4-C9 and muticyclic; and Group V, C6-C11 and multicyclic.15 In each group, the even-numbered α-carbon serves as the nucleophile and attacks the odd-numbered carbonyl via an aldol condensation to form a new 6-membered ring. Group V NRPKSs are unique in that they lack the C-terminal fused TE/CLC domain that catalyzes Claisenlike C-C bond formation and product release. Instead, a standalone metallo-β-lactamase-type thioesterase (MβL-TE) is typically encoded in the vicinity of the NRPKS within the gene clusters.16 Recently, two Group V NRPKSs, AptA17 from Aspergillus nidulans and ACAS16 from Aspergillus terreus, were linked to the biosynthesis of the anthraquinone asperthecin (apt) 3 and anthracenone athrochrysone 5 (Scheme 1), respectively. Each cluster contains a standalone MβL-TE (AptB and ACTE) gene. In the biosynthesis of 5, atrochrysone carboxylic acid was shown to be hydrolyzed off the ACP domain of ACAS by ACTE and then spontaneously decarboxylated to yield 5.16

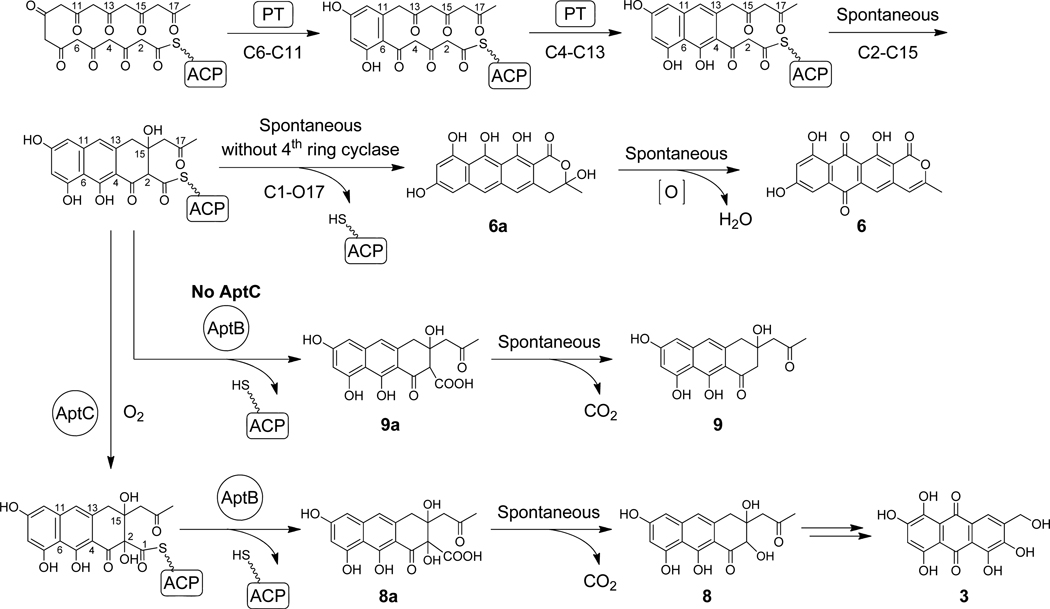

The Group V PKS VrtA from Penicillium aethiopicum was recently linked to the biosynthesis of the tetracyclic naphthacenedione core of 4.18 Comparing the vrt and apt gene clusters revealed that although the structures of 4 and 3 differ significantly, the protein sequences of the core PKS genes are remarkably similar. VrtA and the associated MβL-TE VrtG share high sequence similarities to AptA and AptB (60% and 62% identity, respectively). The activities of the VrtA and AptA PT domains were shown to be functionally equivalent when spliced into different NRPKSs.15 For example, when inserted into a nonaketide (C18) NRPKS, the nascent polyketide was cyclized by either Group V PT domain through C6-C11 and C4-C13 aldol condensations to afford a bicyclic intermediate (Scheme 2).15. The third ring is likely spontaneously cyclized via C2-C15 aldol addition. Subsequently, in the absence of additional enzymatic modifications, spontaneous O17-C1 α-pyrone formation results in the release of the pyranoanthracenone 6a, which is dehydrated and oxidized into 6 (Scheme 2). In the biosynthesis of 4 from a decaketide (C20) backbone, the VrtA-PT is likely to function in a similar way to generate the bicyclic intermediate through the programmed cyclization steps. However, in order to form the tetracyclic naphthacenedione, an additional Claisen-like condensation between C18 and C1 must take place regioselectively following formation of the tricyclic intermediate. The enzymatic basis of this reaction has not yet been elucidated.

Scheme 2.

Biosynthetic pathway of 3 and related shunt products.

Because of the similarities between the core PKS genes in the anthracenone and naphthacenedione biosynthetic pathways, a comparative investigation involving the mix and match of individual enzymes may reveal insights into the mechanism of the fourth ring cyclization. Although the biosynthetic locus of 4 has been identified,18 the requirement of the unusual malonamyl starter unit has complicated the investigation of VrtA functions. As a result, the acetate-primed TAN-1612 1 (neuropeptide Y antagonist) from Penicillium claviforme FL-2733719 was identified as our naphthacenedione target in this study (Scheme 1). A related compound BMS-192548 2 (neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist) was isolated from Aspergillus niger WB2346 and is likely tautomerized from 1 during purification.20 For parallel biosynthetic investigation of a fungal anthracenone, the apt pathway that produces 3 is selected. The anthraquinone 3 is likely derived from an anthracenone precursor such as 5. Here, we first mined the biosynthetic gene cluster of 1 (gene cluster designated as ada, 2-acetyl-2-decarboxamidoanthrotainin) from A. niger ATCC 1015 using Group V PKS PT sequence as a lead. Characterizations of the biosynthetic pathways of 1 and 3 through heterologous reconstitution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in vitro biochemical investigations uncovered that the C18-C1 fourthring Claisen-like condensation is catalyzed by a dimanganese MβL-TE and is dependent on C2-hydroxylation by a flavin-dependent hydroxylase. The MβL-TE is the first example of TE in polyketide biosynthesis that catalyzes the Claisen-like condensation without an α/β hydrolase fold and forms no covalent bond with the substrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Culturing Conditions

A. niger ATCC 1015 was obtained from NRRL and cultured at 28°C. The E. coli strain XL-1 Blue (Stratagene) and TOPO10 (Invitrogen) were used for DNA manipulation, and BL21(DE3) (Stratagene) was used for protein expression. BAP1 described by Pfeifer et al. was obtained from Prof. Khosla.21 S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA (MATα ura3-52 trp1 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 pep4::HIS3 prb1Δ1.6R can1 GAL) was used as the yeast expression host.22 S. cerevisiae transformants were selected with the appropriate complete minimal dropout agar plates, and cultured in YPD medium with 1% dextrose at 28°C.

General Techniques for DNA Manipulation

A. niger genomic DNA was prepared using the ZYMO ZR fungal/bacterial DNA kit according to supplied protocols. PCR reactions were performed with Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, NEB) and Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). PCR products were subcloned into pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Restriction enzymes (NEB) and T4 ligase (Invitrogen) were used to digest and ligate the DNA fragments, respectively. Primers used to amplify the genes were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies and are listed in Table S1.

Construction of pYR311

pBARGPE1 (obtained from FGSC) is a fungal expression vector and contains the A. nidulans gpdA promoter and trpC terminator.23 adaR was amplified from A. niger genomic DNA with primers adaR-f and adaR-r. The resulting DNA fragment was digested with EcoRI and XhoI and inserted in to pBARGPE1 (digested with EcoRI and XhoI) to yield pYR311.

Transformation of A. niger with pYR311

Polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation of A. niger was conducted essentially as described previously for A. nidulans, except that the protoplasts were prepared with 3 mg/mL lysing enzymes (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 mg/mL Yatalase (Takara Bio.).18,24 Glufosinate used for the selection of bar transformants was prepared as previously described.18 Miniprep genomic DNA from A. niger transformants was prepared according to previous procedures for the screening.25 Transformants were cultured in the presence of 4–8 mg/mL glufosinate for screening.18 Integration of the AdaR-overexpression cassette was confirmed by PCR using GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega) and two pairs of primers: bar-f and bar-r, GPE-gpdA-f and adaR-r.

Expression analysis by Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

The total RNA of A. niger mutants and wild-type strains were extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy plant mini kit following the supplied protocols. The first strand cDNA was synthesized using the gene specific reverse primers (adaA-r, adaB-r, β-tub-r) and Improm-II reverse transcription system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was then amplified with GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega) using three pairs of primers: adaA-r and adaA-PT-f, adaB-r and adaB-f, β-tub-r and β-tub-f.

Purification and Characterization of Compounds

The A. niger transformant T4 producing 1 was cultured on 1 L GMM agar for 3 days at 28°C. The agar was extracted three times with equal volume of ethyl acetate (EtOAc). The resultant organic extracts were combined, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude extract was then washed with hexane, and redissolved in 1:1 methanol (MeOH)-chloroform (CHCl3). A Sephadex LH-20 column was used to fractionate the crude extract with 1:1 MeOH-CHCl3 as the mobile phase. Fractions that contained 1 were combined and dried. The residue was redissolved in HPLC grade MeOH and purified by reverse-phase HPLC (Alltech Alltima 5 µm, 250 mm × 10 mm) on a linear gradient of 35 to 95% acetonitrile (CH3CN, v/v in water) over 60 minutes and 95% CH3CN (v/v) over 15 minutes at a flow rate of 2 mL/min. 1D and 2D NMR of 1 were performed on a Bruker DRX-500 spectrometer using CDCl3 as the solvent. 7, 8, 9 and 10 were extracted from a 2L YPD culture of the corresponding S. cerevisiae transformants, purified and analyzed in deuterated NMR solvents (MeOD for 7, acetone-d6 for 8 and 9, DMSO-d6 for 10) using similar procedures. The extraction and purification of 7 requires acidic condition.

Construction of S. cerevisiae Expression Plasmids

pKOS518-120A and pKOS48-172b are 2µ-based yeast-E.coli shuttle plasmids containing different auxotrophic markers (TRP1 and URA3, respectively).26 Primers used to amplify adaA, adaB, adaC, adaD are listed in supplemental Table S1. adaA was amplified by PCR from A. niger genomic DNA with the primers adaA-f and adaA-r and inserted into pCR-Blunt. The resulting vector was digested with SpeI and PmeI and the adaA gene was ligated in pKOS48-172b digested with SpeI and PmlI to yield pYR291. Similar methods were used to insert adaB, adaC and adaD in pKOS518-120A digested with NdeI and PmeI to yield pYR301, pYR313 and pYR315, respectively. The ADH2p-adaC-ADH2t cassette was obtained by digesting pYR313 with SalI and XhoI, and inserting the fragment into the pYR301 digested with XhoI to yield pYR330. The ADH2p-adaD-ADH2t cassette obtained by digesting pYR315 with HindIII and XhoI, and inserting the fragment into pYR330 digested with HindIII and SalI to yield pYR342. The expression plasmids for apt genes were constructed using similar methods, except aptA was inserted in the pKOS48-172b digested with NdeI and PmlI to yield pYR203; aptB and aptC were inserted in the pKOS518-120A digested with NdeI and PmeI to yield pYR204 and pYR260, respectively. The ADH2p-aptC-ADH2t cassette was obtained by digesting pYR255 with SalI and XhoI, and was inserted into pYR204 digested with SalI to yield pYR260. The introns of adaB, aptA, aptB, aptC were removed by using splice by overlapping extension (SOE)-PCR.

Reconstitution and Investigation of the Biosynthetic Pathway of 1 in S. cerevisiae

Various combinations of the expression plasmids were introduced into S. cerevisiae strain BJ5464-NpgA22 by using the S. c. EasyCompTM Transformation Kit (Invitrogen). The cells were grown at 28°C in 10 mL YPD media with 1% dextrose. For product detection, 1 mL of cell culture was collected and analyzed every 12 hours after induction for 72 hours. The medium was extracted with equal volume of 99% EtOAc/1% acetic acid (AcOH), and the cell pellets were extracted with 100 µL acetone. The organic phase was separated, evaporated to dryness, redissolved in 20 µl MeOH and analyzed with a Shimadzu 2010 EV Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometer (LC-MS, phenomenex Luna 5 µm, 2.0 × 100 mm) using both positive and negative electrospray ionization. Compounds were separated on a linear gradient of 5% CH3CN (v/v in water, 0.1% formic acid) to 95% CH3CN (v/v in water, 0.1% formic acid) over 30 min with a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min.

Construction of E. coli Expression Plasmids

The DNA fragments encoding AdaA, AdaC, AptB and AptC were each inserted into pET24 digested with NdeI and NotI to yield pYR303, pYR316, pYR146 and pYR201, respectively. The site-directed mutants of AptB were constructed through SOE-PCR and inserted into pET24. The DNA fragments encoding AptA was inserted into pET28 digested with NdeI and EcoRI to yield pYR62.

Expression and Purification of Enzymes

Expression and purification procedures of AdaA, AdaC, AptB, AptC, AptA and MatB followed identical procedures. The expression and purification of AdaA is detailed here as an example. pYR303 was used to transform the BAP1 for protein expression.21 The cells were cultured at 37°C and 250 rpm in 500 mL LB medium supplemented with 35 µg/mL kanamycin to a final OD600 between 0.4 and 0.6. The culture was then incubated on ice for 10 min before addition of 0.1 M isopropylthio-β-d-galactoside (IPTG) to induce protein expression. The cells were further cultured at 16 °C for 12–16 h. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation (3,500 rpm, 15 min, 4°C), resuspended in ~25 mL lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) and lysed by sonication on ice. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation (15,000 rpm, 30 min, 4°C), and Ni-NTA agarose resin was then added to the supernatant (1–2 mL/liter of culture). The suspension was swirled at 4°C for 2 h and loaded into a gravity column. The protein-bound resin was washed with one column volume of 10 mM imidazole in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT), followed by 0.5 column volume of 20 mM imidazole in buffer A. The protein was then eluted with 250 mM imidazole in buffer A. Purified AdaA was concentrated and exchanged into Buffer A+10% glycerol with the centriprep filters (Amicon), aliquoted and flash frozen using acetone/dry ice. Protein concentration was determined with the Bradford assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard.27 For the expression of Mn2+-AptB or Fe2+-AptB, 200 ppm of MnSO4 or FeSO4 was added to the expression media. Metal contents of various AptB and mutations were determined using an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AES, TJA Radial IRIS 1000).

In vitro Reconstitution of Enzymes

The reactions were performed at 100 µL scale containing 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in the presence of 100 mM sodium malonate, 2 mM DTT, 7 mM MgCl2, 20 mM ATP, 5 mM coenzyme A, 20 µM MatB, with various combinations of NRPKSs and the tailoring enzymes.28 Typically, the concentration of the NRPKS (i.e. AptA or AdaA) was 10 µM and the tailoring enzymes (i.e. AdaC, AptB, AptC) were 50 µM. The reactions were quenched with 1 mL of 99% EtOAc/1% AcOH. The organic phase was separated, evaporated to dryness, redissolved in 20 µL of DMSO and analyzed with LC-MS as previously described.

RESULTS

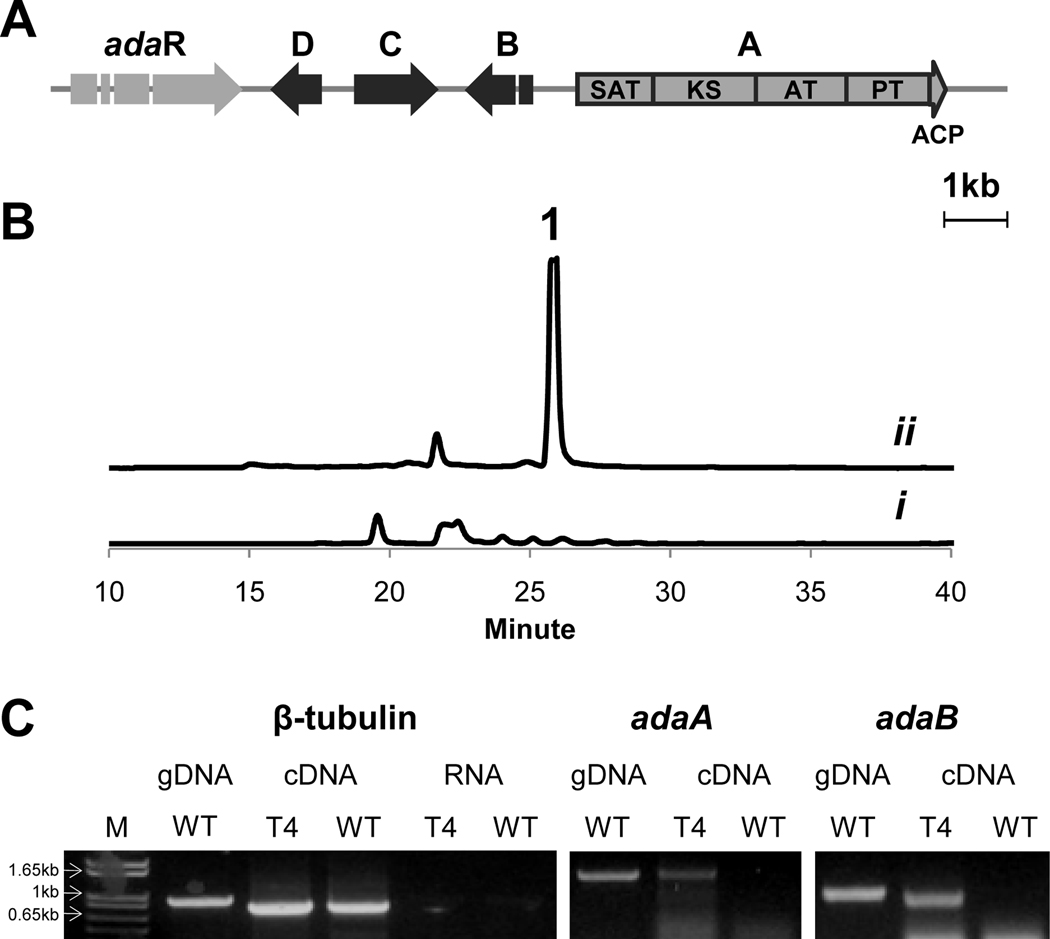

Mining of the ada Gene Cluster in A. niger

Although A. niger WB2346 is the only A. niger species reported to produce 1,20 we postulated that the genome-sequenced A. niger strains may also contain gene clusters that can biosynthesize 1. To test this idea, we scanned the sequenced genomes of A. niger ATCC 1015 and CBS513.8829 for genes encoding Group V NRPKSs. A BLAST search of both genomes with AptA-PT15 uncovered a unique Group V NRPKS gene (An11g07310) in the CBS 513.88 strain. The corresponding ortholog (e_gw1_4.29) is also found in the ATCC 1015 strain, but the coding region is incomplete. The gaps were filled by PCR and sequencing, which revealed that the Group V NRPKSs encoded in both strains share >98% protein sequence identity (Table 1). The gene products downstream of the A. niger ATCC 1015 NRPKS (named AdaA) include a putative MβL-TE AdaB, a FAD-dependent monooxygenase (FMO) AdaC, an O-methyltransferase (O-MeT) AdaD and a putative Zn2Cys6 family transcription regulator AdaR. (Figure 1A, Table 1). The core biosynthetic enzymes AdaA, AdaB and AdaC all show very high sequence similarities to the corresponding apt and vrt enzymes (Table 1). We reason that the decaketide backbone of 1 may be synthesized and cyclized by AdaA. While the C15-OH of 1 is expected to be retained from an acetate unit during the C2-C15 aldol addition as in the biosynthesis of 5, the C2-OH may be added by the FMO AdaC,16 which is a homolog of AptC.17 AdaD then performs the C9 O-methylation to complete the biosynthesis of 1. Since the anthracenone hydrolysis activity observed for the close homolog ACTE is not applicable here, the role of the MβL-TE AdaB in the formation of 1 is not yet clear. Given that no additional enzyme from this putative gene cluster appears likely as a fourth ring Claisen cyclase, we propose that AdaB may be involved in facilitating the C18-C1 C-C bond formation and concomitant release of 1.

Table 1.

Genes Within the ada Cluster From Aspergillus niger ATCC 10151

| Gene | Size (bp/aa) |

A. niger CBS 513.88 (% identity) |

BLASTP homolog |

Identity/ Similarity (%) |

E-value | Conserved Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adaA | 5382/1793 | An11g07310 (99) |

aptA vrtA |

69/80 | 0.0 | NRPKS, SAT-KS-MAT-PT-ACP |

| 59/74 | 0.0 | |||||

| adaB | 1005/317 | An11g07320 (100) |

aptB vrtG |

69/79 | 1e-177 | metallo-β-lactamase superfamily |

| 62/76 | 1e-107 | |||||

| adaC | 1245/414 | An11g07320 (100) |

aptC vrtH |

63/79 | 8e-153 | UbiH and related FAD-dependent oxidoreductases |

| 63/78 | 2e-153 | |||||

| adaD | 750/249 | An11g07340 (99) | vrtF | 60/71 | 2e-68 | methyltransferase domain type12 |

| adaR | 2504/777 | An11g07350 (100) | vrtR2 | 42/55 | 1e-128 | GAL4-like Zn(II)2Cys6 binuclear cluster DNA-binding domain |

The sequence of the ada gene cluster in A. niger ATCC 1015 was deposited in GenBank with accession number JN257714.

Figure 1.

Induction of the ada gene cluster. (A) Organization of the ada gene cluster. (B) LC analysis (400 nm) of A. niger extracts: i. WT and ii. T4 transformant; (C) RT-PCR analysis of the ada genes with lane M as marker. The β-tubulin was used as a positive control and RNA only of both WT and T4 was used as negative controls. Regions of adaA and adaB were probed for inducted transcription.

Culturing of A. niger ATCC 1015 in different media and under various growth conditions did not lead to the production of 1 (Figure 1B, trace i), suggesting that the biosynthesis of 1 may be silent. Overexpression of pathway-specific transcriptional regulators has been a successful strategy for activating cryptic metabolic pathways in fungi.30 AdaR is likely involved in the regulation of the ada gene cluster and maybe similarly overexpressed to activate the biosynthetic pathway. To do so, adaR was placed under the regulation of the A. nidulans gpdA promoter (Pgpda) in pBARGPE1,23 which carries the bar gene.31 The resulting plasmid pYR311, was transformed into A. niger ATCC 1015. Several glufosinate-resistant colonies exhibited yellow pigmentation on agar plates not observed in the wild type (WT) strain when grown on glucose minimal medium (Figure S1). Insertion of the PgpdA::adaR and the bar resistant gene into the pigmented transformants T1–T5 were confirmed by PCR (Figure S1). Pigmented agar of one transformant (T4) was then extracted and analyzed by LC-MS (Figure 1B, trace ii, Figure S2). A new compound at RT (retention time) = 26.2 min, with a UV spectrum and m/z consistent to those reported for 1 was overproduced in T4 (Figure 1B).19 RT-PCR analysis of adaA and adaB confirmed activated transcriptions of both genes in the T4 strain but not in WT, which supports the involvement of the ada gene cluster in the biosynthesis of the yellow pigment in the strain (Figure 1C).

The yellow pigment was subsequently purified from T4, extensively characterized by NMR, and confirmed to be 1 (Figure S3, Table S3). Taken together, these results verified the proposed correlation between the ada gene cluster and the biosynthesis of 1 in A. niger ATCC 1015. Overexpression of adaR led to an increased titer of 1 in A. niger ATCC 1015 from undetectable levels to ~ 400 mg/L, which represents a 100-fold increase compared to the titer reported from A. niger WB2346 (2.9 mg/L).20b

Heterologous reconstitution of ada and apt pathways in BJ5464-NpgA

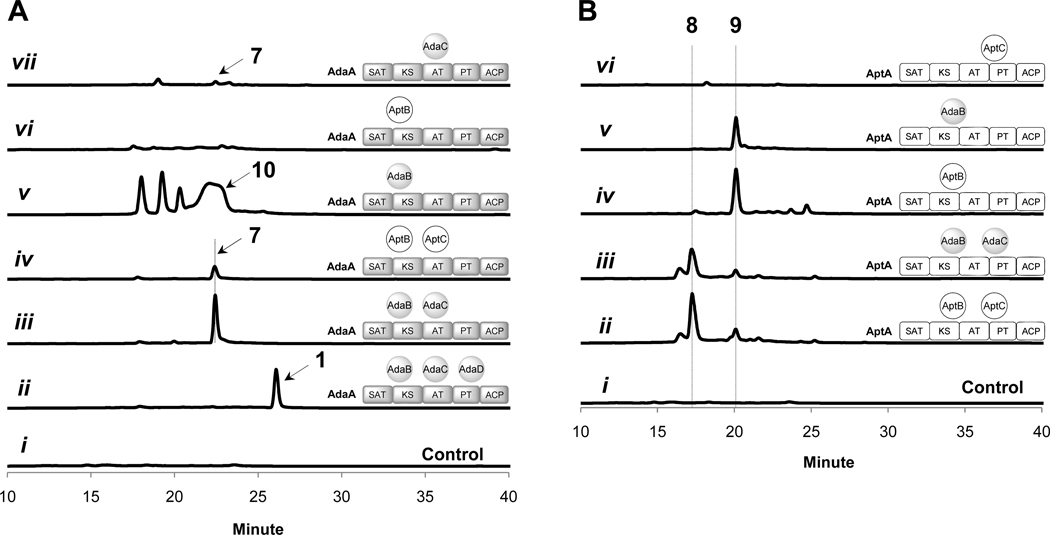

To verify if the four-enzyme ensemble (AdaA-D) is sufficient for the biosynthesis of 1, we reconstituted the putative four-gene pathway in S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA, which is a vacuolar protease-deficient strain carrying the A. nidulans phosphopantetheinyl transferase npgA.22 The intron-free coding sequences of the four genes were amplified from A. niger ATCC 1015 genomic DNA using SOE-PCR and placed under the control of the ADH2 promoter. Two resulting yeast 2µ expression plasmids pYR291 (carrying adaA) and pYR342 (carrying adaB-D) were transformed into BJ5464-NpgA (Table S2). The two-day culture of the yeast transformant synthesized 1 as essentially the only polyketide product with a titer of ~ 10 mg/L (Figure 2A, trace ii, Table 2). Subsequently, AdaD was excluded from the heterologous host (Table S2) and the resulting strain produced a new compound (~8 mg/L) with UV spectrum (Figure 2A, trace iii, Table 2) and mass (m/z [M+H]+ = 401) consistent with that of 7 (Figure S4, Scheme 3). The structure of 7 was verified to be the C9-hydroxyl version of 1 by NMR analysis (Figure S5, Table S4), which confirmed that AdaD is indeed the C9-O-methyltransferase. The efficient production of 7 in BJ5464-NpgA shows that AdaA, AdaB and AdaC are sufficient for the biosynthesis of a naphthacenedione, and sets the stage for more systematic investigation into the roles of each enzyme in the yeast host. In subsequent studies, adaD was excluded from the heterologous host/plasmid combinations.

Figure 2.

LC analysis (400 nm) of polyketides synthesized by coexpression of different combinations of ada and apt genes in S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA. (A). AdaA coexpressed with different combinations of MβL-TEs and/or FMOs; (B) AptA coexpressed with different combinations of MβL-TEs and/or FMOs. Control trace is extracted from untransformed BJ5464-NpgA culture.

Table 2.

Heterologous expression of different combinations of apt and ada genes and the resulting products1.

| NRPKS | MβL-TE | FMO | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| adaA | adaB | adaC | 7 |

| aptA | aptB | aptC | 8 |

| adaA | aptB | aptC | 7 |

| aptA | adaB | adaC | 8 |

| aptA | aptB | - | 9 |

| adaA | adaB | - | 10 |

| adaA | aptB | - | nd2 |

| aptA | adaB | - | 9 |

| adaA | - | adaC | 7 |

| aptA | - | aptC | nd |

S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA is the host;

nd no polyketide metabolite was detected from this combination of genes.

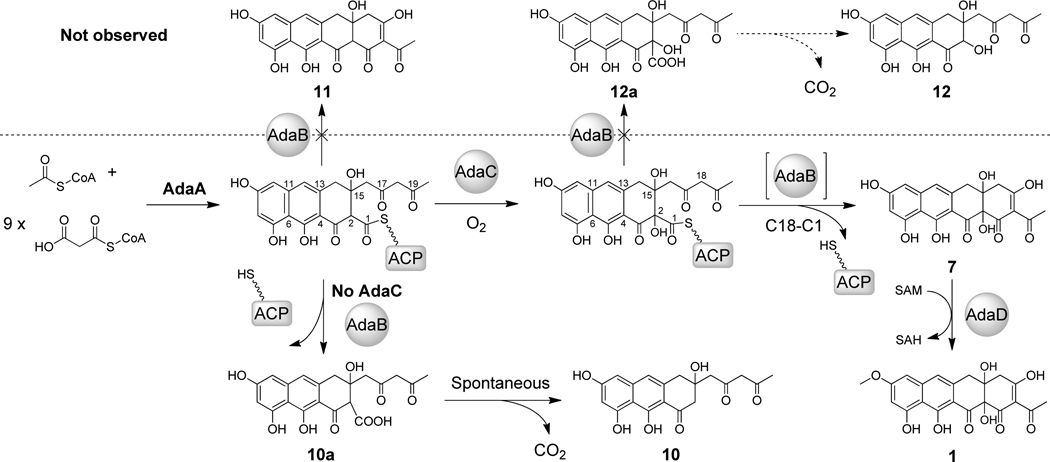

Scheme 3.

Biosynthetic pathway of 1 and related shunt products.

Using the same approach as above, we reconstituted the activities of AptA, AptB and AptC from the biosynthetic pathway of 3. The two expression plasmids encoding the three apt genes (pYR203 and pYR260, Table S2) were introduced into BJ5464-NpgA, and the resulting strain synthesized a new compound 8 (m/z [M+H]+ = 333) (Figure 2B, trace ii, Figure S6). The molecular weight of 8 agrees with that of a nonake-tide that has undergone two dehydrations, one decarboxylation and one hydroxylation. This was surprising since we originally anticipated the NRPKS AptA to be an octaketide (C16) synthase based on the size of the final product 3.17 8 was purified from the yeast culture and the structure was established to be a multiply hydroxylated anthracenone (Scheme 2, Figure S7, Table S5). The coordinated activities of AptA, AptB and AptC in the biosynthesis of 8 are shown in Scheme 2. The conversion of 8 to 3 may require additional A. nidulans enzymes encoded outside of the compact apt cluster.

Comparative analysis of the ada and apt pathways through gene shuffling

The heterologous reconstitution of AdaA-C and AptA-C clearly demonstrate these two sets of highly similar enzymes synthesize the structurally distinct 7 and 8, respectively. This raises the obvious question of how hydrolysis of 8 and fourth-ring cyclization of 7 may be accomplished by the corresponding MβL-TEs, which are highly similar in sequence (Table 1). To dissect the roles of each enzyme and the biochemical differences between the homologous enzymes, we constructed various shuffled pathways in BJ5464-NpgA (Table 2). When AptA was combined with the ada tailoring enzymes AdaB and AdaC, biosynthesis of anthracenone 8 was observed as the major product with similar yield as the intact apt pathway (Figure 2B, trace iii, Table 2). This indicates that AdaB and AdaC can efficiently function on a smaller, nonaketide substrate. Conversely, coexpression of AptB and AptC with AdaA produced 7 as the major product, albeit at a yield that is ~10-fold lower than the intact ada pathway (Figure 2A, trace iv, Table 2). The lower yield may be attributed to the less efficient function of AptC or AptB on the larger decaketide substrate (more evidence on this later). The biosynthesis of 7 and 8 by these shuffled pathways implicates that i) the polyketide chain length control lies in the NRPKSs AdaA and AptA; ii) both the MβL-TE and the FMO in the two pathways can process substrates of unnatural chain lengths and are therefore functionally homologous (with some differences in efficiency); and iii) most importantly, both MβL-TEs appear to be bifunctional and can catalyze either hydrolysis (towards the formation of 8), or the Claisen-like fourth-ring cyclization (towards the formation of 7) when the substrate is of sufficient chain length (C20).

We next excluded either AptC or AdaC from the reconstituted pathways to verify the role of the FMO and the necessity of the modification to subsequent steps. When only AptA and AptB were expressed in BJ5464-NpgA, a major product 9 with a mass of 316 was recovered. (Figure 2B, trace iv, Figure S8, Table 2). Following large scale culture and NMR characterizations, the structure of 9 was shown to be identical to 8 except the absence of C2-OH (Figure S9, Table S6). This single structural difference between 8 and 9 confirms that AptC is the C2-hydroxylase (Scheme 2). Following thioester hydrolysis by AptB to release 9a, spontaneous decarboxylation occurs to afford the anthracenone 9. The C2-hydroxylation does not appear to affect the hydrolytic activities of AptB since both 8 and 9 were produced at comparable levels (~10 mg/L) from the heterologous yeast host. As expected, substitution of AptB with AdaB also resulted in hydrolysis and production of 9 (Figure 2B, trace v, Table 2).

On the other hand, coexpression of AdaA and AdaB in BJ5464-NpgA did not yield 11, which is an analog of 7 that is unhydroxylated at C2 (Scheme 3). Instead, the resulting strain synthesized 10 (m/z [M+H]+ = 359) (Figure 2A, trace v, Table 2, Figure S10), the molecular weight of which is consistent with a decaketide that has undergone two dehydrations and one decarboxylation. The structure of 10 was analyzed by NMR (Figure S11, Table S7) and was confirmed to be a tricyclic, 1,3-diketone-containing anthracenone (Scheme 3). Compared to 9, 10 contains an additional ketone at C18 that is reflective of the longer polyketide backbone synthesized by AdaA. While the absence of the C2-hydroxyl also verifies the role of AdaC, the failure of AdaA and AdaB to synthesize 11 in the absence of AdaC hints that C2-hydroxylation may be essential for the Claisen cyclization. In the absence of the C2-OH modification, AdaB acts as a hydrolytic TE to release the diketo-anthracenone carboxylic acid 10a from AdaA, which then spontaneously decarboxylates to form 10. This result supports the timing of C2-hydroxylation to precede cyclization as shown in Scheme 3. Therefore, the α-hydroxylation step appears to be crucial for switching the nucleophile in the chain releasing step catalyzed by AdaB, from a hydroxide ion to the C18 enolate anion. Lastly, BJ5464-NpgA transformants expressing AdaA and AptB did not produce any obvious products (Figure 2A, trace vi, Table 2). This indicates a subtle difference between the two MβL-TEs in the hydrolysis reaction: while AdaB can hydrolyze both C18 and C20 anthracenone-S-ACP substrates to yield 9 and 10, respectively, AptB can only hydrolyze the C18 substrate to yield 9.

To probe whether offloading of 7 and 8 indeed requires the MβL-TE, we coexpressed the individual NRPKSs with their corresponding FMO only. BJ5464-NpgA expressing aptA and aptC did not produce any polyketide (Figure 2B, trace vi), confirming that nonenzymatic hydrolysis to yield 8a does not occur. In contrast, BJ5464-NpgA expressing AdaA and AdaC produced trace amounts of 7 (Figure 2A, trace vii). Hence the C18-C1 Claisen cyclization can take place uncatalyzed with very low efficiency, and is significantly enhanced by AdaB.

In vitro Biosynthesis of 7 and 8

To complement the heterologous biosynthesis results, we reconstituted the synthesis of 7 and 8 using purified enzymes. His6-tagged AptA and AdaA were expressed and purified from E. coli BAP1,21 while the other enzymes (AptB, AptC, AdaC) were expressed and purified from BL21(DE3). AptB purified from the culture medium without supplementation of metal ions is designated as AptB*. Soluble forms of AdaB could not be obtained from E. coli and is therefore not included in the assays. Purified AptC and AdaC were thermally denatured and the prosthetic groups were confirmed to be FAD by LC-MS analysis as previously described (Figure S12).32 To generate malonyl-CoA in situ for use in polyketide turnover assays, we used the malonyl-CoA synthetase MatB from Rhizobium trifolii to produce the extender units from malonate, ATP and CoA.28

Upon mixing AptA, AptB* and AptC in the presence of the required reagents and cofactors for 12 hours, the organic products were analyzed by LC-MS. In agreement with the heterologous reconstitution results, the in vitro reaction produced 8 as the dominant product, while excluding AptC from the reaction yielded 9 (Figure 3A, traces i and ii). When AptB and AptC were both absent from the reaction mixture, AptA synthesized 6 from the spontaneous lactonization of the fourth ring (Figure S13), which was previously observed with other hybrid Group V nonaketide NRPKS.15 Therefore, the activities observed in the yeast host can be completely recapitulated by using purified enzyme components. To test if the hydroxylation of C2 occurs on the free standing substrate 9 to yield 8, AptC was assayed with 9 in the presence of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). However, no conversion was observed (Figure S14), which is in agreement with the proposed mechanism that AptC hydroxylates the anthracenone carboxyl thioester attached to the AptA-ACP (Scheme 2).

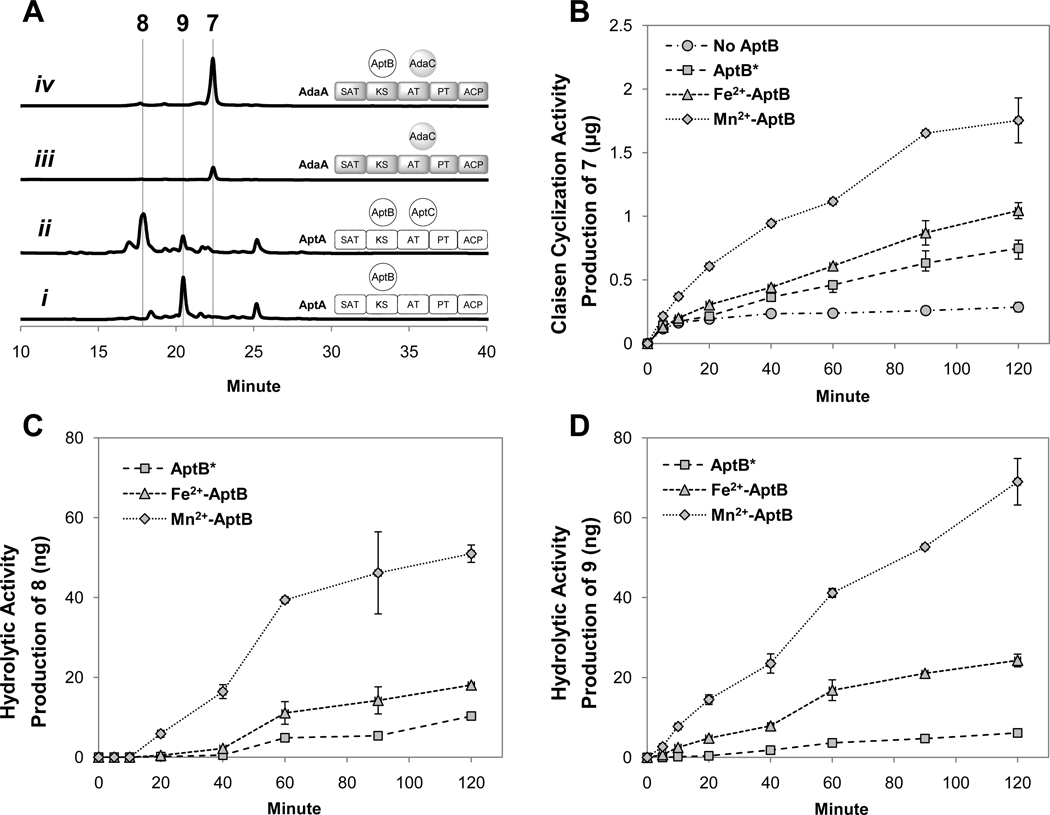

Figure 3.

In vitro reconstitution of AptB activities. (A) LC analysis (400 nm) of polyketide synthesized from different combinations of purified enzymes; (B–D). Time-course analysis of production of 7, 8, or 9 over 120 minutes using AptB containing different levels of metal cofactors (AptB*, Fe2+-AptB and Mn2+-AptB) coincubated with AdaA and AdaC (B), AptA and AptC (C), and AptA only (D). No hydrolysis can be observed in the absence of AptB.

In vitro reactions using purified components also enabled us to prove the trace amounts of 7 synthesized by AdaA and AdaC is not an artificial result from the actions of endogenous yeast enzymes. Indeed, release of small amounts of 7 can be detected after overnight incubation of AdaC and AdaA (Figure 3A, trace iii). Inclusion of AptB* in the assay, however, led to a higher level synthesis of 7 (Figure 3A, trace iv). To quantify the role of AptB* in accelerating the cyclization, we monitored the time-course production of 7 by using an HPLC assay (Figure 3B). Following the reaction progress from 5 to 120 minutes after initiation showed that AptB* can increase the turnover of 7 up to 3-fold in two hours.

Combining the in vivo and in vitro results, the dual catalytic functions of fungal PKS MβL-TEs such as AdaB and AptB can be established as shown Schemes 2 and 3. In both cases, the MβL-TE is responsible for product turnover. First, MβL-TE catalyzes the hydrolysis of anthracenone carboxylic acids such as 9a and 10a from the NRPKS with certain chain-length specificities; second, when the decaketide anthracenone carboxyl-S-ACP is hydroxylated at C2 by the FMO, the MβL-TE accelerates the Claisen-like condensation between C18 and C1 to release the naphthacenedione product from the NRPKS.

Biochemical Characterization of AptB as a Bifunctional TE

As proposed in the study of ACTE, MβL-TEs belong to the metallo-β-lactamase (MβL) superfamily, and consist of the conserved divalent metal binding motif HXHXDH.16 In addition, alignment of the sequences of AptB, AdaB, VrtG and ACTE shows that these MβL-TEs are similar to the subclass B3 MβLs (Figure S15),33 which employ a HXHXDH(X)iH(X)jH motif to bind two divalent transition metal ions such as Zn2+ and Fe2+. The metal contents of AptB* was determined by ICP-AES, and showed that AptB* contains Fe2+, Mn2+ and Ni2+ ions and more than 55% of AptB* has no metal ions in either of the metal binding sites (Table S8). We believe that Ni2+ ions originated from the affinity purification step. As zinc ions are naturally abundant, the presence of Zn2+ in AptB* at such low concentration suggests the unlikelihood of Zn2+ being the physiological cofactor. Dialysis of AptB* with 10 mM EDTA led to significant precipitation, likely due to instability of the apo AptB as a result of metal loss. ICP-AES data on AptB* that remained in solution showed a significant decrease in the metal content of divalent metal ions other than Mn2+ (Table S8), which suggests that the other metal ions (Fe2+, Ni2+, Zn2+) are loosely bound in AptB*. To obtain a higher percentage of AptB in holo form, 200 ppm of MnSO4 or FeSO4 was supplemented to the AptB expression medium. The metal content of AptB purified from the Mn2+-enriched medium (Mn2+-AptB) was determined to be 1.5 Mn2+ cations per monomer (Table S8), while Fe2+-AptB (purified from Fe2+-enriched medium) contained 0.9 Fe2+ and 0.4 Mn2+ cations per monomer (Table S8). This evidence strongly suggests dinuclear Mn2+ as the physiologically preferred metal cofactor of AptB. Dialysis of Mn2+-AptB with 10 mM EDTA did not result in notable precipitates, indicating the enzyme-Mn2+ interactions are strong.

The catalytic functions of AptB*, Fe2+-AptB and Mn2+-AptB were then compared by measuring the time courses of in vitro production of 7, 8 or 9 (Figure 3B–D). As shown in Figure 3B–D, Mn2+-AptB is much more efficient (up to three to four-fold higher in product turnover) in catalyzing both the hydrolysis and Claisen-like condensation than Fe2+-AptB and AptB*. In the presence of Mn2+-AptB, the apparent production rate of 7 is ~ 17 ng/min, while that of 8 or 9 is ~25-fold lower at 0.7 ng/min. Therefore, even though the natural role of AptB in the apt pathway is hydrolysis to yield 9a, it can promote the C18-C1 Claisen-like condensation much more efficiently than the hydrolysis reaction under the assay conditions.

To visualize the metal binding sites, we generated a homology structural model of AptB from the I-TASSER server (Figure 4A, left panel).34 Comparative analysis with the previously reported structures of MβL superfamily enzymes, such as ST158535 from Sulfolobus tokodaii (Figure 4A, right panel) and YcbL36 from Salmonella enteric serovar Typhimurium, suggests that H97, H99, D101, H102, H153 and H207 of AptB are the six residues that chelate the two Mn2+ cations. Among them H97, H99 and H153 are predicted to bind one Mn2+ atom, while D101, H102 and H207 are predicted to bind the other Mn2+.37 In addition, the binuclear Mn2+ ions are normally bridged with a hydroxide ion and an aspartate side chain, which is from the conserved D172 among AptB, AdaB and VrtG (Figure 4A, Figure S15).37

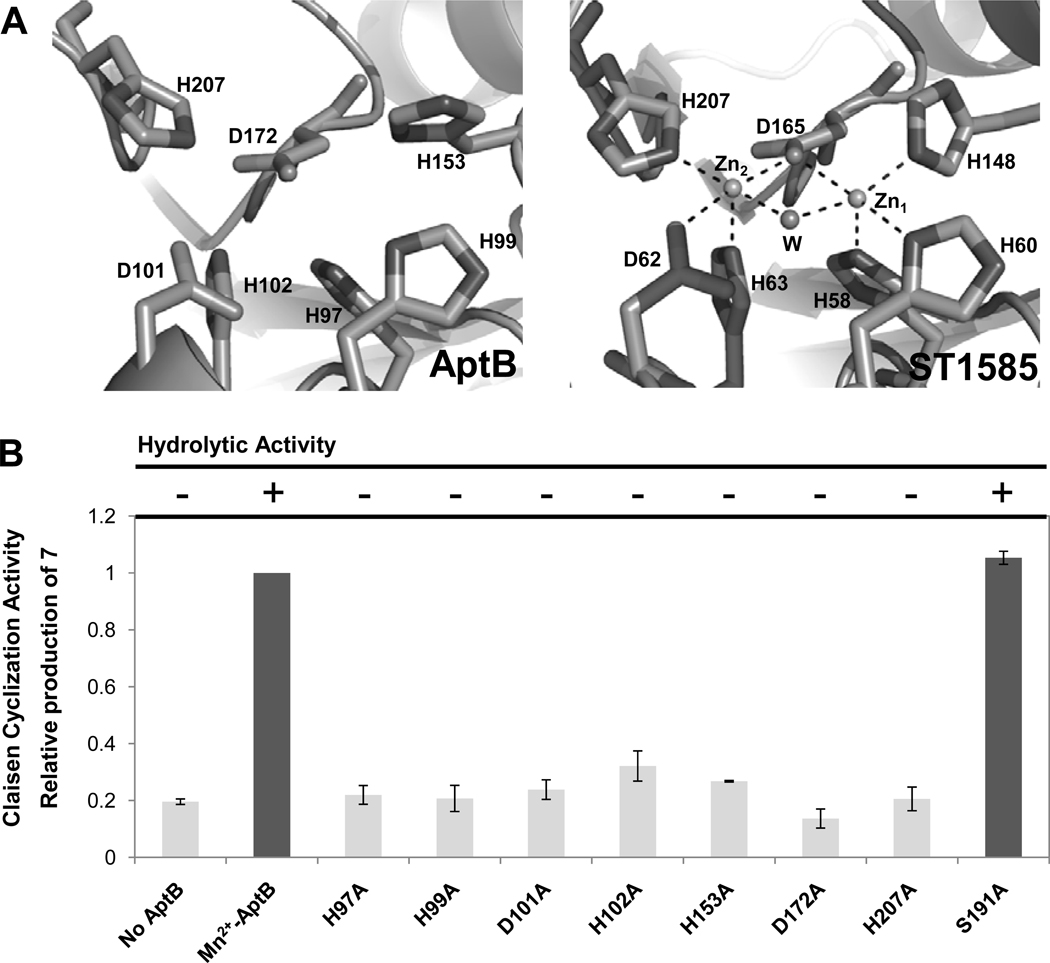

Figure 4.

Structural modeling and mutational analysis of AptB. (A) Comparison between the modeled metal binding sites of AptB (left) predicted by the I-TASSER server and the zinc binding site of a MβL superfamily protein ST1585 (Chain B) (adapted from ref 35) (right). (B). Site directed mutagenesis of AptB to probe the hydrolysis (formation of 9) and Claisen condensation (formation of 7) activities. The level of production of 7 in the wild-type Mn2+-AptB assay is defined as 1 for comparison of the catalytic activity of the Mn2+-AptB mutants.

Site-directed mutations to alanines at these seven residues in Mn2+-AptB were then performed to confirm their roles in metal binding and catalytic activity. All these mutants were expressed and purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) in the Mn2+-enriched medium with similar yields as the wild type Mn2+-AptB. Secondary structure analysis using far-UV circular dichroism confirmed that the mutants did not undergo significant structural changes when compared to Mn2+-AptB or apo-AptB (Figure S16). The hydrolytic activities of these mutants were assayed along with AptA and estimated by the production of 9; whereas the Claisen-like cyclization activities were assayed in the presence of AdaA/AdaC and estimated by the relative levels of 7 (wild type Mn2+-AptB is defined to be 1). As expected, the hydrolytic activities of these seven mutants (H97A, H99A, D101A, H102A, H153A, D172A and H207A) were completely abolished, while the levels of 7 were attenuated to that of uncatalyzed levels with AdaA/AdaC alone (Figure 4B). As expected, ICP-AES analysis revealed the loss of both Mn2+ ions by most of the mutants, and the loss of one ion in H102A and H207A AptB (Table S8). Therefore, chelation of both Mn2+ ions are essential for the activities of AptB, which is in contrast to the well-studied dimanganese arginase in which loss of one metal binding site leads to partial loss of enzyme activity.38

DISCUSSION

In this work, we have successfully utilized the PT phylogenetic classification to locate the gene cluster for the biosynthesis of the fungal naphthacenedione 1. The connection between the ada gene cluster and biosynthesis of 1 was confirmed by overexpressing the pathway-specific transcriptional regulator AdaR in A. niger. The gene cluster of 1, including the NRPKS, is highly similar to those synthesize anthracenones. Subsequent parallel investigations with ada and apt core PKS enzymes in S. cerevisiae led to the identification of a group of bifunctional MβL-TEs that can catalyze both hydrolysis and Claisen cyclization.

AptB is a Dimanganese Enzyme that Catalyzes C-C Bond formation

The MβL enzymes belong to the broader family of hydrolytic metalloenzymes.39 The hydrolytic activity of MβLs is both dependent on the electrostatic activation of the proton on the metal-coordinated water molecule and the consequent formation of the hydroxide ion (OH−).37 Zn2+ as the hardest Lewis acid among the first row of transition metals, is most utilized among the MβLs.40 Our investigation suggests that AptB is different from most MβLs and does not bind Zn2+. Instead, AptB exhibits preferential catalytic and physiological requirements for two Mn2+ cations. A number of hydrolytic dimanganese enzymes have been reported,41 including the best characterized arginase,42 inorganic pyrophosphatase43 and aminopeptidase.44 AptB is the first example among the binuclear manganese enzymes that can catalyze C-C bond formation through Claisen-like condensation. Based on sequence alignment and homology modeling to other MβL-TEs, each Mn2+cation in AptB is likely penta-coordinated in a trigonal bipyramidal geometry (Figure 4A). Mutating any of the metal-coordinating residues to alanine (H97A, H99A, D101A, H102A, H153A, D172A and H207A) led to the loss of both the Claisen cyclization and hydrolysis activities.

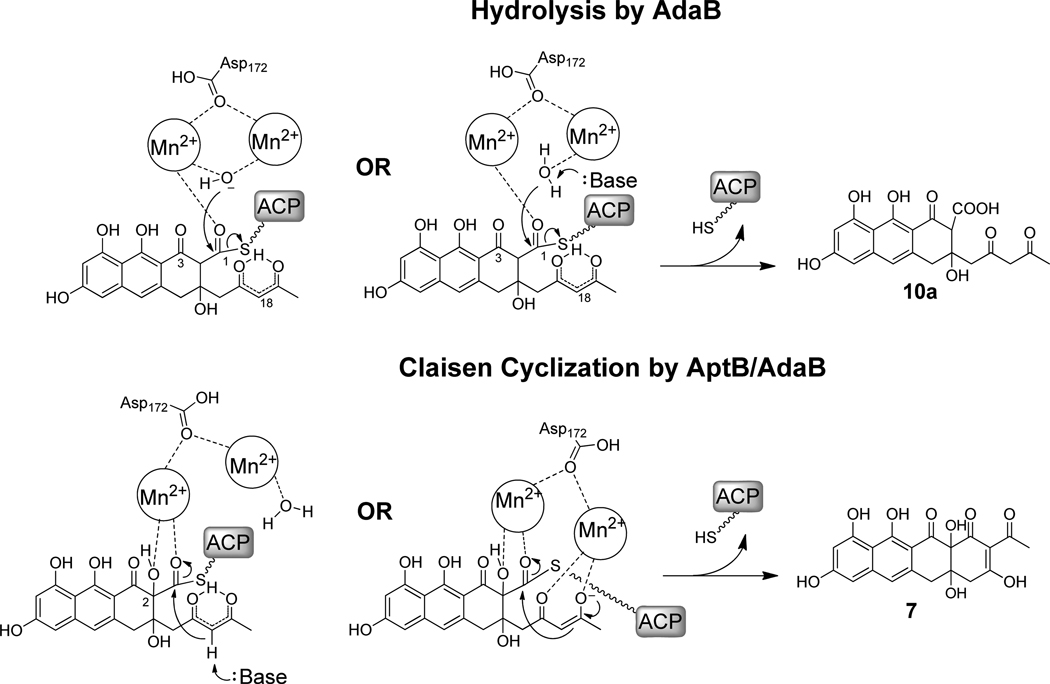

Proposed Mechanism of the Hydrolysis Reaction

AptB can facilitate the turnover of naphthacenedione 7 more than 20 times faster than towards anthracenone 8 or 9 (Figure 3B–D). This was surprising considering AptB is naturally recruited by the apt pathway to perform the hydrolytic release of 8a. This suggests that the active site environment of AptB, including positioning of the two Mn2+ cations, is optimally setup to perform the Claisen-like condensation, while the hydrolysis reaction occurs when the thioester is placed in close proximity to a strong hydroxide ion. Hence we could expect the hydrolytic reaction to be nonspecific towards substrates that have similar structure and hydrophobicity. Indeed, when AptB was added to the in vitro reaction containing the lovastatin nonaketide synthase (LNKS) LovB and the enoylreductase LovC, AptB was also able to catalyze the hydrolytic release and turnover of the otherwise stalled dihydromonacolin (data not shown).45 Other types of cyclization TE domains in PKSs, including those that have α/β hydrolase folds, have also been noted to display substantial substrate promiscuity in the loading and hydrolysis of nonnative acyl-thioesters.13a,46

The hydrolytic mechanism of AptB and AdaB likely resembles that of other dimanganese metalloenzymes such as arginase (Scheme 4).41c,42 For example, the dimanganse stabilizes the highly reactive hydroxide ion under physiological pH, which serves as the nucleophile in attacking the C1 thioester of the tricyclic polyketide intermediates to yield 9a and 10a. The dependence of hydrolytic activity on both Mn2+ suggests that the Mn2+ ions may play additional roles in catalysis not seen with those in arginase, in which the catalytic center is the metal-ion loaded in the M1 site and the enzyme is active with a mononuclear center.38 Here, one of the Mn2+ ions in AptB may play a crucial role in stabilizing the oxyanion generated in the tetrahedral intermediate. Alternatively, in a model similar to that proposed by Dismukes for arginase,47 one of the Mn2+ may be involved in substrate binding through coordination to the C1 (or even C3) carbonyl oxygen (as well as stabilizing the oxyanion hole), whereas the other Mn2+ chelates a water molecule. During catalysis, a general base such as a nearby histidine can deprotonate the water to initiate the hydrolysis reaction.

Scheme 4.

Proposed enzymatic mechanism of MβL-TE.

Proposed Mechanism of the α-Hydroxylation Dependent Claisen Cyclization

The comparatively weak hydrolytic activity of AptB suggests that the Claisen cyclization is its true function. Our studies here reveal that the cyclization of 7 requires C2-hydroxylation by the accompanying of FMO (AdaC or AptC). If the decaketide substrate is not C2-hydroxylated, the corresponding cyclization product 11 is not observed. Conversely, upon C2-hydroxylation, no hydrolysis product such as 12a (and the decarboxylated product 12) can be detected (Scheme 3). Therefore, the α-hydroxylation step essentially functions as a nucleophile switch that modulates the dual functions of AptB. Insertion of the tertiary hydroxyl group α to the C1 thioester carbonyl can have profound effects in substrate reactivity and conformation. This is evidenced in the slow but detectable spontaneous cyclization of 7 in the absence of AptB when C2 is hydroxylated. In contrast, the hydrolysis of 8a cannot be observed without AptB. The C2-OH can disrupt the keto-enol tautomerization across C1 and C3, thereby increasing the electrophilicity of C1 for nucleophilic attack. Additionally, the C2-hydroxyl group may hydrogen bond to the C1-carbonyl and may provide stabilizing effects to the tetrahedral intermediate. However, these electronic effects should be observed in both hydrolysis and Claisen cyclization reactions, and therefore cannot be used solely to explain the “nucleophile switching” role of this modification.

Although the absolute stereochemistries of 7 and 1 are unknown, the C2-OH is mostly like in the (R) configuration and is syn to the C15-OH as seen in the crystal structure of 4.48 The syn configuration may lead to rearrangement of the flexible C17-C19 diketone moiety, such as through hydrogen bonding, and position the C18 nucleophile in a more favorable position for catalysis. Furthermore, this stereochemical configuration can lead to the possible positioning of a cluster of oxygen atoms, including those on C1, C2, C15, C17 and C19 on the same face of the substrate and are all within suitable distances for chelating both Mn2+ ions when bound to AptB. Such chelation may significantly increase the binding affinity of the substrate in the active site. For example, one of the Mn2+ ions can chelate to both C2-OH and C1 carbonyl to yield a five-membered-ring (Scheme 4). Such kind of penta-ring structure is not unprecedented, and has been seen in dihydroxyacetone phosphate chelating a Zn2+ cation in E. coli class II fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase.49 In this mode, the water molecule only chelates to the other Mn2+ ion and sufficient rearrangement of the active site may prevent deprotonation required for hydrolysis. The general base is instead positioned more favorably to deprotonate the C18 α-carbon.

Alternatively, in addition to the five-membered ring formed through coordination to the first Mn2+, there is a possibility that the C17-C19 diketone moiety can be coordinated to the second Mn2+ ion following substrate conformation changes induced by C2-hydroxlylation (Scheme 4). This indeed represents the most favorable model for the Claisen cyclization, and is similar to that seen with aldolases.50 The coordination of C17 and C19 carbonyls strongly favors the formation of the enol and deprotonation of C18 without the requirement of a general base. The displacement of the hydroxide or water ligand on the second Mn2+ should also completely suppress the hydrolysis reaction. Additional biophysical and structure studies on this novel Claisen cyclase is needed to understand the exact modes of substrate binding and metal coordination.

The Bifunctional MβL-TEs are different from the TE/CLC domains

The α-hydroxylation-dependent Claisen cyclization strategy employed by AptB and AdaB is different from the mechanism used by TE/CLC domain found in many NRPKSs, such as those involved in the biosynthesis of bikaverin, 51 naphthopyrone13b and aflatoxin.13a During the Claisen-like cyclization catalyzed by TE/CLC, the active site serine forms an oxyester bond with C1 of the polyketide substrate, releasing it from the phosphopantetheinyl-arm of the ACP. Formation of the covalent intermediate was suggested to reorient the nucleophilic α-carbon with respect to the Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad and enables formation of the enol.13a The reaction then proceeds via deprotonation of the α-carbon and nucleophilic attack on C1. From the vastly different reaction mechanisms, it is not surprising that fungal TE/CLC and MβL-TE share no sequence similarity. Sequence alignment of AptB, AdaB and VrtG does indicate a conserved serine residue (S191 for AptB, Figure S15), however, mutation to alanine in AptB did not affect the efficiency of the Claisen cyclization (Figure 4B). Therefore, MβL-TEs employ a completely different mechanism to enolize the α-carbon, and no covalent bond is formed between the polyketide intermediate and the MβL-TEs during the cyclization. Furthermore, in the biosynthesis of fungal aromatic polyketides requiring TE/CLC domains, the C1 carbonyl is usually directly connected to an aromatic ring due to the C2-C7 or C4-C9/C2-C11 cyclization steps catalyzed by PT, and the hyperconjugation between the aromatic ring and C1 carbonyl reduces the reactivity of C1. Therefore, the covalently bound enzyme-substrate intermediate is required to promote the cyclization reaction in TE/CLC.

In contrast, bacterial type II PKSs infrequently perform the final ring closure through Claisen cyclization, except in the biosynthesis of tetracyclines and aureolic acids. Anhydrotetracycline52 and premithramycinone,53 the key intermediates in tetracycline and aureolic acid biosynthesis, respectively, share similar naphthacenedione scaffolds. Correspondingly, the biosynthesis steps also involve a C18-C1 Claisen-like ring closure. The electronic environment of the α-carbon is more similar to substrates of the TE/CLC cyclized reactions, in that the C1 carbonyl is directly connected to and conjugated with the aromatic portions of the molecules. Therefore, although the exact catalytic mechanism of the C18-C1 fourth ring cyclization in bacteria has not been completely established, most likely it will be different from the fungal strategy described here.

Phylogenetic Analysis of MβL-TEs

During phylogenetic analysis of PT domains, the Group V NRPKSs were branched into two major subgroups. Interestingly, their corresponding MβL-TEs can also be classified into two subgroups (Figure S17) with similar phylogenetic distribution to their paired NRPKSs, indicating that the NRPKS/MβL-TE may be coevolved. The first subgroup (Group V1) contains ACTE and AN0149, while the second subgroup (Group V2) contains AdaB, AptB and VrtG. AN0149 has been linked to the biosynthesis of the anthraquinone emodin, which is likely synthesized via an anthracenone intermediate as in the biosynthesis of 5 involving ACTE.16 Hence, the classification of MβL-TE is largely based on the sizes of the polyketide substrates. The fourth ring cyclization mechanism of Group V2 MβL-TEs should be common to the biosynthesis of fungal tetracyclic naphthacenedione compounds, such as 4, hypomycetin and anthrotainin. To investigate if the Claisen cyclization activity is universal among both groups of MβL-TEs, we also purified and assayed ACTE with AdaA and AdaC. However, formation of 7 was not accelerated, which indicates that the Claisen cyclization activity is unique among the Group V2 MβL-TEs.

The presence of several uncharacterized PKS clusters with the Group V2 NRPKS/MβL-TE/FMO three-gene ensemble in other sequenced fungal genomes (Figure S6) indicates that there are potentially other undiscovered fungal tetracyclic compounds. Based on the presence of FMOs in all analyzed Group V2 PKS clusters and their absence in all Group V1 PKS clusters, it is likely that the Group V2 MβL-TEs were diverged from the hydrolytic Group V1 MβL-TEs and acquired the Claisen cyclase function during the recruitment of FMO into these pathways. The fact that AptB exhibits higher efficiency in catalyzing the Claisen cyclization than hydrolysis, and the presence of the unique FMO in the apt cluster suggest that AptB may have been part of a tetracyclic pathway, but reverted to its hydrolytic function more recently. This is perhaps due to the loss of ability to produce the longer decaketide chain by the NRPKS AptA. Most identified enzymes in the MβL superfamily are known to catalyze hydrolytic reaction, such as the well-known β-lactamase that confers penicillin resistance. Therefore, the hydrolytic activity is likely the ancestral role of these newly identified MβL-TEs with fourth ring cyclization activity.

In conclusion, this study sheds light into the mechanism of biosynthesis of anthracenone and naphthacenedione in fungi. Compared to the biosynthesis of naphthacenedione in bacteria, such as premithramycinone and anhydrotetracycline that require over ten enzymes, the fungal strategy is concise and only involves three enzymes. The linear polyhydroxylated tetracyclic compounds have been a promising source of bioactive molecules, which include clinically important antibiotics and antitumor drugs. The establishment of the minimal three-gene ensemble (Group V NRPKS/ MβL-TE/FMO) required for the biosynthesis of a fungal naphthacenedione provides a useful signature feature for discovery of other related compounds from fungi using genome mining. Furthermore, the demonstrated ability to produce tetracyclic naphthacenedione in yeast has opened up new possibilities to engineer these pharmacologically attractive tetracyclic scaffolds.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Prof. Neil Garg, Dr. Stuart Haynes, Dr. Hui Zhou, Dr. Jaclyn Winter, Xue Gao and Wei Xu for their helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grants 1R01GM085128 and 1R01GM092217 to YT.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ATP

adenosine-5'-triphosphate

- CoA

coenzyme A

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- NADPH

reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- MβL-TEs

metallo-β-lactamase-type thioesterase

- NRPKS

non-reducing polyketide synthase

- SAT

starter unit:ACP transacylase

- KS

ketosynthase

- MAT

malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase

- PT

product template

- ACP

acyl carrier protein

- ICP-AES

inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer

- SOE

splice by overlapping extension

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- EtoAC

ethyl acetate

- MeOH

methanol

- CHCl3

chloroform

- CH3CN

acetonitrile

- AcOH

acetic acid

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- IPTG

isopropylthio-β-d-galactoside

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. NMR, UV and LC-MS characterization of compounds described in the main text; protein sequence alignments and additional experimental information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Hagan D. The Polyketide Metabolites. Chichester, UK: Ellis Howard; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Das A, Khosla C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:631. doi: 10.1021/ar8002249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hertweck C, Luzhetskyy A, Rebets Y, Bechthold A. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:162. doi: 10.1039/b507395m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhou H, Li Y, Tang Y. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:839. doi: 10.1039/b911518h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox RJ. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:2010. doi: 10.1039/b704420h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawford JM, Thomas PM, Scheerer JR, Vagstad AL, Kelleher NL, Townsend CA. Science. 2008;320:243. doi: 10.1126/science.1154711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris CM, Roberson JS, Harris TM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:5380. doi: 10.1021/ja00433a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe A, Fujii I, Sankawa U, Mayorga ME, Timberlake WE, Ebizuka Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Hutchison RD, Steyn PS, Van Rensburg SJ. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1973;24:507. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(73)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jesus A, Hull W, Steyn P, Heerden F, Vleggaar R. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1982;1982:902. [Google Scholar]; (c) Zheng C-J, Yu H-E, Kim E-H, Kim W-G. J. Antibiot. 2008;61:633. doi: 10.1038/ja.2008.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford JM, Townsend CA. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:879. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crawford JM, Dancy BCR, Hill EA, Udwary DW, Townsend CA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:16728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Zhang WJ, Li YR, Tang Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:20683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809084105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Crawford JM, Korman TP, Labonte JW, Vagstad AL, Hill EA, Kamari-Bidkorpeh O, Tsai S-C, Townsend CA. Nature. 2009;461:1139. doi: 10.1038/nature08475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wattana-amorn P, Williams C, Ploskon E, Cox RJ, Simpson TJ, Crosby J, Crump MP. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2186. doi: 10.1021/bi902176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroken S, Glass NL, Taylor JW, Yoder OC, Turgeon BG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:15670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2532165100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Korman TP, Crawford JM, Labonte JW, Newman AG, Wong J, Townsend CA, Tsai SC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913531107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fujii I, Watanabe A, Sankawa U, Ebizuka Y. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:189. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey AM, Cox RJ, Harley K, Lazarus CM, Simpson TJ, Skellam E. Chem. Comm. 2007:4053. doi: 10.1039/b708614h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Xu W, Tang Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awakawa T, Yokota K, Funa N, Doi F, Mori N, Watanabe H, Horinouchi S. Chem. Biol. 2009;16:613. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szewczyk E, Chiang YM, Oakley CE, Davidson AD, Wang CC, Oakley BR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:7607. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01743-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chooi Y-H, Cacho R, Tang Y. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:483. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishimaru T, Tsuboya S, Saijo T. JP0556861A. Japanese Patent. 1994

- 20.(a) Kodukula K, Arcuri M, Cutrone JQ, Hugill RM, Lowe SE, Pirnik DM, Shu YZ, Fernandes PB, Seethala R. J. Antibiot. 1995;48:1055. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shu YZ, Cutrone JFQ, Klohr SE, Huang S. J. Antibiot. 1995;48:1060. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeifer BA, Admiraal SJ, Gramajo H, Cane DE, Khosla C. Science. 2001;291:1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1058092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Jones EW. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:428. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94034-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee KK, Da Silva NA, Kealey JT. Anal. Biochem. 2009;394:75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pall ML, Brunelli JP. Fungal. Genet. Newsl. 1993;40:59. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrianopoulos A, Hynes MJ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988;8:3532. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chooi Y-H, Stalker DM, Davis MA, Fujii I, Elix JA, Louwhoff SHJJ, Lawrie AC. Mycol. Res. 2008;112:147. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mutka SC, Bondi SM, Carney JR, Da Silva NA, Kealey JT. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:40. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1356.2005.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradford MM. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.An JH, Kim YS. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;257:395. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2570395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pel HJ, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:221. doi: 10.1038/nbt1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Chiang Y-M, Szewczyk E, Davidson AD, Keller N, Oakley BR, Wang CCC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2965. doi: 10.1021/ja8088185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bergmann S, Schumann J, Scherlach K, Lange C, Brakhage AA, Hertweck C. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:213. doi: 10.1038/nchembio869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson CJ, Movva NR, Tizard R, Crameri R, Davies JE, Lauwereys M, Botterman J. EMBO J. 1987;6:2519. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Fan K, He Y, Xu X, Peng Y, Yu T, Jia C, Yang K. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1055. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Garau G, Garcia-Saez I, Bebrone C, Anne C, Mercuri P, Galleni M, Frere JM, Dideberg O. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2347. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2347-2349.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bush K, Jacoby GA. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2010;54:969. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01009-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5:725. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang Y. BMC Bioinf. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimada A, Ishikawa H, Nakagawa N, Kuramitsu S, Masui R. Proteins. 2010;78:2399. doi: 10.1002/prot.22749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamp AL, Owen P, El Omari K, Nichols CE, Lockyer M, Lamb HK, Charles IG, Hawkins AR, Stammers DK. Protein Sci. 2010;19:1897. doi: 10.1002/pro.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.(a) Wang Z, Fast W, Valentine AM, Benkovic SJ. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1999;3:614. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu D, Xie D, Guo H. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) López V, Alarcón R, Orellana MS, Enríquez P, Uribe E, Martínez J, Carvajal N. FEBS J. 2005;272:4540. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Orellana MS, López V, Uribe E, Fuentes M, Salas M, Carvajal N. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;403:155. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Scolnick LR, Kanyo ZF, Cavalli RC, Ash DE, Christianson DW. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10558. doi: 10.1021/bi970800v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daiyasu H, Osaka K, Ishino Y, Toh H. FEBS Lett. 2001;503:1. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bebrone C. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;74:1686. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Christianson DW. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1997;67:217. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(97)88477-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dismukes GC. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2909. doi: 10.1021/cr950053c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Christianson DW, Cox JD. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanyo ZF, Scolnick LR, Ash DE, Christianson DW. Nature. 1996;383:554. doi: 10.1038/383554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heikinheimo P, Lehtonen J, Baykov A, Lahti R, Cooperman BS, Goldman A. Structure. 1996;4:1491. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilce MC, Bond CS, Dixon NE, Freeman HC, Guss JM, Lilley PE, Wilce JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:3472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma SM, Li JW-H, Choi JW, Zhou H, Lee KKM, Moorthie VA, Xie X, Kealey JT, Da Silva NA, Vederas JC, Tang Y. Science. 2009;326:589. doi: 10.1126/science.1175602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma KK, Boddy CN. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:3034. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khangulov SV, Sossong TM, Jr, Ash DE, Dismukes GC. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8539. doi: 10.1021/bi972874c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kabuto C, Silverton JV, Akiyama T, Sankawa U, Hutchison RD, Steyn PS, Vleggaar R. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1976:728. [Google Scholar]

- 49.(a) Hall DR, Leonard GA, Reed CD, Watt CI, Berry A, Hunter WN. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;287:383. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Galkin A, Li Z, Li L, Kulakova L, Pal LR, Dunaway-Mariano D, Herzberg O. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3186. doi: 10.1021/bi9001166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lipscomb WN, Strater N. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2375. doi: 10.1021/cr950042j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma SM, Zhan J, Xie X, Watanabe K, Tang Y, Zhang W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:38. doi: 10.1021/ja078091o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pickens LB, Tang Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:27509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.130419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lombo F, Menendez N, Salas JA, Mendez C. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;73:1. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0511-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.