Abstract

Pair-bonded relationships form during periods of close spatial proximity and high sociosexual contact. Like other monogamous species, marmosets form new social pairs after emigration or ejection from their natal group resulting in periods of social isolation. Thus, pair formation often occurs following a period of social instability and a concomitant elevation in stress physiology. Research is needed to assess the effects that prolonged social isolation has on the behavioral and cortisol response to the formation of a new social pair. We examined the sociosexual behavior and cortisol during the first 90-days of cohabitation in male and female Geoffroy's tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix geoffroyi) paired either directly from their natal group (Natal-P) or after a prolonged period of social isolation (ISO-P). Social isolation prior to pairing seemed to influence cortisol levels, social contact, and grooming behavior; however, sexual behavior was not affected. Cortisol levels were transiently elevated in all paired marmosets compared to natal-housed marmosets. However, ISO-P marmosets had higher cortisol levels throughout the observed pairing period compared to Natal-P marmoset. This suggests that the social instability of pair formation may lead to a transient increase in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity while isolation results in a prolonged HPA axis dysregulation. In addition, female social contact behavior was associated with higher cortisol levels at the onset of pairing; however, this was not observed in males. Thus, isolation-induced social contact with a new social partner may be enhanced by HPA axis activation, or a moderating factor.

Keywords: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, Glucocorticoid, Sexual behavior, Affiliative behavior, Monogamy, Pair-bonding

1. Introduction

Adult social relationships are essential and beneficial for humans and monogamous animals [1], and long-term social isolation or separation can cause homeostatic dysfunction and detrimental health outcomes [e.g., 2–12; reviewed in 13–15]. Furthermore, stress has an intricate, reciprocal relationship to social bonds. In humans and monogamous species, disruption of the bond between the social pair evokes a significant biobehavioral stress response while maintenance of the pair bond buffers against the negative consequences of a stressful event [e.g., humans (Homo sapiens): 9, 16–18; marmosets (Callithrix kuhlii and C. jacchus): 3, 19, 20; titi monkeys (Callicebus moloch): 21; prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster): 22; guinea pigs (Cavia aperea f. porcellus): 23; dwarf hamsters (Phodopus sungorus and P. campbelli): 24–26; mice (P. californicus and P. eremicus): 5, 27]. This suggests that the maintenance of social bonds may result, in part, from the distress associated with bond disruption or loss and the anxiolytic benefits of social interactions. In addition, there are data that indicate an association between hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation following stressful experiences and the development of social attachment in childhood in humans [28] as well as adulthood in monogamous animals [29, 30]. However, the biosocial mechanisms underlying such affiliative responses to stress remain largely unknown. The current research aims to test the effects of prior psychosocial stress on the formation and maintenance of a new social relationship in a monogamous primate utilizing an ethologically valid model of stress, social isolation in marmoset monkeys.

While cohesive same-sex social networks are the mode for primates, social monogamy between a single male and female as the primary social relationship occurs in a limited number of primate species [31–33]. Besides humans, the majority of monogamous primate groups are forest-dwelling arboreal species [34], which include marmoset monkeys of the genus Callithrix. Marmosets typically establish stable, long-term heterosexual relationships that are defined by high rates of sociosexual behavior and contact [35–37], preference for a familiar social partner [38–40; cf. 36], and intruder-directed aggression [41–44]. Like other monogamous species, marmosets form new social pairs after emigration or ejection from their natal group typically resulting in periods of social isolation [45, 46; reviewed in 47] and often coinciding with an increase in stress physiology, particularly elevated plasma cortisol levels – an end-point of the HPA axis [48–51].

The periods of courtship and formation of heterosexual social relationships may regulate homeostatic HPA activity both transiently and in the long-term. In humans, both men and women have marked increases in salivary cortisol when presented with a sexually attractive confederate of the opposite-sex [52–54]. Men and women who report that they had recently fallen in love have significantly higher plasma cortisol levels than single, uncommitted participants [55]. In nonhuman primates, cortisol in male marmosets becomes elevated following a brief sexual encounter with a receptive female [56], but not after a brief encounter with a novel male [57]. In addition, cortisol is elevated during the initial weeks of pairing compared to several weeks or months after the onset of pairing in male and female marmosets [50, 51, 58]. As patterns of partner-directed social behaviors critical for the formation and quality of the social partnership are being established during the same period of HPA activity regulation [37], we suggest that social interaction with a partner may regulate or be influenced by HPA activity in marmosets, as has been previously suggested for other monogamous species [59].

The present study examines the hypothesis that stress associated with social isolation is capable of altering HPA axis function and promoting bond-related social behavior in marmosets. The goals were to (1) document the sociosexual behavior during pair formation, (2) determine if prior social isolation alters the behavioral and physiological responses to establishing new heterosexual pairs, and (3) compare cortisol levels during the initial pairing to the partner-directed behavior throughout the pairing period in male and female Geoffroy's tufted-ear marmosets (C. geoffroyi). Together, these data may provide some insight into the impact that social isolation and function of the HPA axis has on social bonding in marmosets.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Subjects were 21 adult-aged Geoffroy's tufted-ear marmosets from 12 natal groups living in their natal groups [Age: M = 3.1 yrs, SE = 0.3]). While controlling for genetic bias, marmosets were randomly divided into one of three groups: (1) adult-aged marmosets that remained in their natal group (Natal; 4 males and 4 females), (2) marmosets that were removed from their natal group and immediately paired with a novel, opposite-sex conspecific (Natal-P; 2 males and 3 females), and (3) marmosets that were removed from their natal group and paired with a novel, opposite-sex conspecific after a period of long-term social isolation (ISO-P; 4 males and 4 females). All marmosets were housed in colony rooms at the Callitrichid Research Center (CRC) at the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO). Colony rooms at the CRC were maintained at a temperature range of 19.0 – 22.0°C and a 12h:12h light-dark cycle. Natal-, single-, and paired-housing enclosures were wire-meshed cages (minimum 0.8 m3 per animal) and equipped with branches, nest boxes, other assorted enrichment items, and opaque panels to prevent any visual contact between groups. All other dietary and husbandry information were consistent with CRC protocol and can be reviewed in Schaffner et al. [37]. All animal use procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol#: 07-033-FC). The CRC is a registered research facility with the U.S.D.A., and is accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquaria (AZA). All appropriate guidelines for housing and conducting research with animals were followed.

2.2. Pairing and behavioral observations

Marmosets from the Natal-P (n =5) and ISO-P (n = 8) groups were selected to create male-female pairs that were unrelated and unfamiliar to each other. For the ISO-P group, adult marmosets were removed from their natal group due to either scheduled removal or following a disruption in the natal group that lead to the ejection of the adult offspring from the group. These subjects were placed in a single-housing enclosure, isolated from visual and social contact with conspecifics with limited olfactory and vocal communication for long-term periods that ranged from 6 – 20 weeks (M = 13.7, SE = 1.9). The variance in the isolation period was a result of the unscheduled ejections that lead to changes in the pairing schedule for subjects. These pairs were formed by simultaneously introducing males and females into a novel cage in the morning (0900-1000 h). In one case, one experimental female was introduced into the home cage of a male; however, only the female in this pair was included into the analysis. Twenty min behavioral observations were conducted between 0900 and 1500 h approximately 3 to 5 days a week through the first 90 days of pairing. Before each observation period, animals were allowed several minutes to acclimate to the presence of the observer. The interactions between the male and female were recorded to observe social, sexual, aggressive, and territorial/communicative behaviors and maintenance of spatial proximity between the pair, previously described in Smith et al. [60]. The establishment and maintenance of the social partnership was observed using the social and sexual behaviors and social proximity between the pair as described in the literature [35–37, 60]. Aggressive and territorial/communicative behaviors were selected to assess distress between the pair and territorial intergroup communication, respectively [43, 61, 62].

2.3. Urine collection

Urine samples (2-5 samples per 10-day block) were collected during the first 90 days post-pairing from the adult marmosets in the Natal-P and ISO-P condition. Samples were also collected from the Natal group every second or third day during a 10-day block to serve as controls for comparing urinary cortisol levels. Urine collections were done under stress-free conditions, and a more detailed description of this procedure can be found in French et al. [63]. Briefly, all urine samples used in this study were first void samples collected in the morning between 0600 and 0830 h. Animals were trained to urinate into hand-held pans for a preferred food item in their home cages with their partner present. Urine was transferred from the pan with a glass pipette to a microcentrifuge vial and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 3 min. The supernatant portion was transferred to a clean vial and frozen at -20 °C until the time of assaying.

2.4. Cortisol assay

Urine samples were analyzed for cortisol concentrations using a cortisol enzyme immunoassay (EIA). Assay standard sensitivity was set at 7.8 - 1000 pg Cort/50μl. Samples were diluted 1:6400 in distilled-deionized water and 50 μl of this solution were taken to assay. The inter-assay coefficient of variation, calculated from pooled urine analyzed on each plate, was 15.79%. The average intra-assay coefficient of variation, also calculated from pooled urine analyzed on each plate, was 2.77%. To minimize the possible confounding effects of inter-assay variation, samples for each animal were run on the same day and in a single assay when applicable. To control for variations in fluid intake and urine solute concentration, we divided the concentration of Cort by the concentration of creatinine (Cr), a muscle metabolite that is excreted at near-constant rates. Cr concentrations were determined using a modified Jaffe endpoint assay [64]. Further details of the assay validation can be found in Smith and French [65].

2.5. Statistical analyses

The sociosexual behavior and excreted urinary cortisol levels for male and females during pairing were averaged across 10-day blocks for the first 90 days post pairing. All behaviors and cortisol measures were compared in a three-way repeated measures ANOVA comparing prior stress condition (social isolation or unstressed), behavior or cortisol across the 90 days, and the sex of the marmoset. Only the main effect for each variable and the two-way interaction between pairing duration and the other two variables were evaluated. Therefore, the two- way interaction between social condition and the sex of the marmoset and the three-way interaction between the three variables were not evaluated due to the small sample size. In addition, a one-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the effect of housing and stress condition (natal housing, paired after isolation housing, or paired directly from natal housing) on urinary cortisol levels during the first 10-days of pairing, or a random 10-day block in natal housing. Fisher's LSD was used as the post-hoc analysis for all significant main effects and interactions. The average excreted cortisol levels during the first 10 days of pairing were correlated with the average of each behavior over 10-day blocks during the first 90 days of pairing by Pearson's correlations. All alpha levels were set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Selective sociosexual behavior during cohabitation

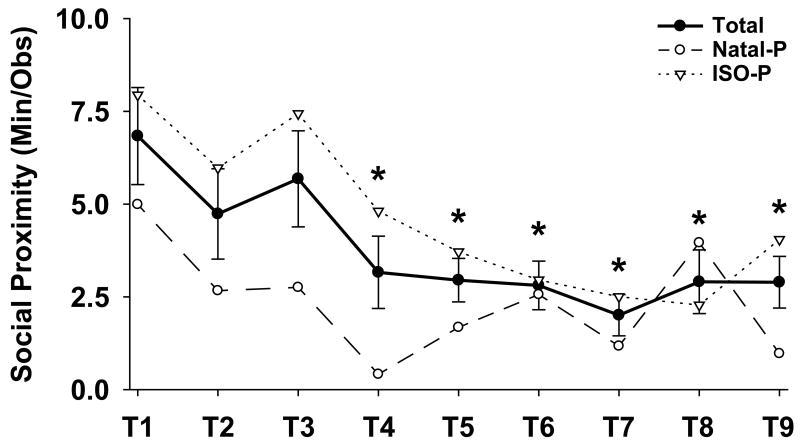

Social proximity between the pair was highest during the first 10-day block and dropped over the subsequent eight 10-day blocks, averaging at about an eighth of the time after the first month, [see Fig. 1; F (8,48) = 3.80, p < 0.005]. ISO-P marmosets were in close proximity to their social partners almost twice as often than Natal-P marmosets, [see Table 1; F (1,6) = 5.54, p < 0.05]. Although not significant, ISO-P marmosets tended to groom their partner more often than Natal-P marmosets throughout the 90 days of pairing, [see Table 1; F (1,8) = 4.15, p = 0.07].

Fig. 1.

Social proximity (mean ± SEM) during pairing and by prior stress condition. Time periods (T2-T9) labeled with an asterisk differ significantly by post hoc Fisher's LSD test from the first 10-day block (T1), p < 0.05.

Table 1. Effect of social isolation on behavior and cortisol during pairing.

| Condition | Social proximitya | Allogroomingb | Cortisolc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natal-P | 2.35 ± 0.76 | 0.08 ± 0.19 | 17.18 ± 2.09 |

| ISO-P | 4.63 ± 0.59 | 0.53 ± 0.11 | 24.77 ± 1.98 |

| p-value | < 0.05 | 0.07 | < 0.05 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Units include

Min/Obs,

Freq/Obs, and

μg/mg Cr

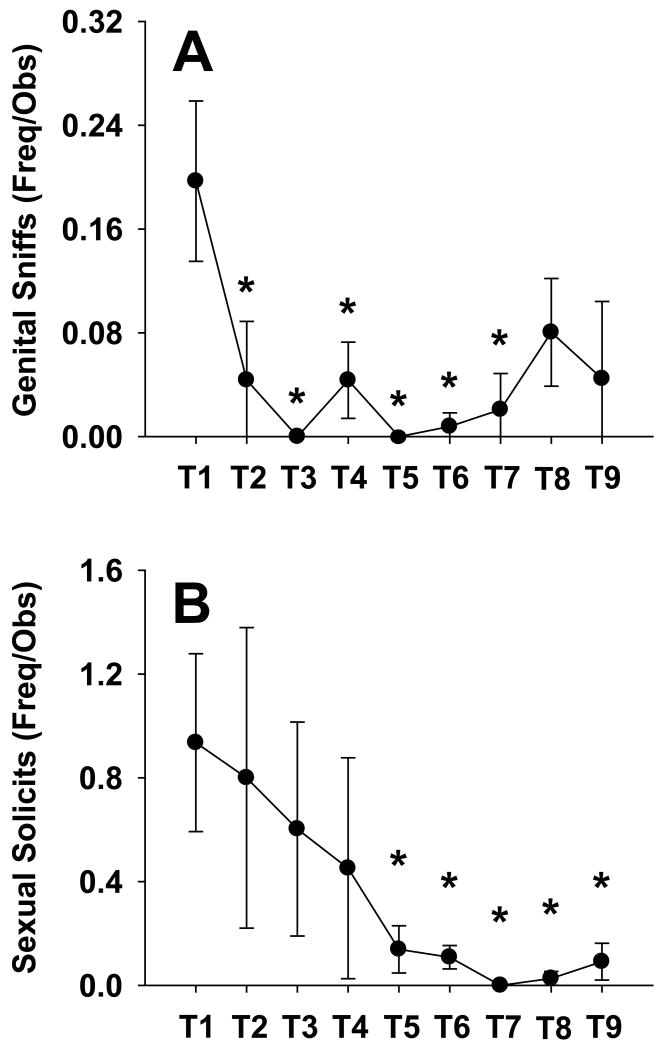

Sexual behavior was not affected by prior chronic social isolation; however, the display of sexual solicitations dropped significantly after the initial 10-days of pairing. Particularly, male and female marmosets displayed more sexual investigation, i.e., genital sniffing, during the first 10-days of pairing and rates of these behavior patterns dropped over the subsequent 80-days, [see Fig. 2a; F (8,72) = 3.29, p < 0.005]. Sexual solicitation, such as lip-smacking and tongue flicking, were observed more at the onset of the pairing and significantly dropped by the fifth 10-day block compared to the first 10-day block, [see Fig. 2b; F (8,72) = 2.21, p < 0.05]. In addition, there was a main effect such that the frequency that males mounted and attempted to mount their new female social partners differed across the pairing period [F's (8,32) > 2.89, p's < 0.05]. However, there were no significant differences between any 10-day block in the post-hoc analysis, although there was a pattern for males to mount and attempt mount more during the first 10-day block than any subsequent time. There were no interactions between pairing duration and the prior housing condition. Besides the trend effect of males approaching their partners more often than females, there were no main effects of sex or interaction between pairing duration and sex for any of the behaviors observed. Finally, physical aggression was not observed during the pairing period, and vocal aggression was observed infrequently and only occurred during the first 10-days of pairing (<10 occurrences observed). As a result, statistical analyses were not able to be conducted for aggressive behavior.

Fig. 2.

Sexual behavior (mean ± SEM) during pairing. (A-B) Time periods (T2-T9) labeled with an asterisk differ significantly by post hoc Fisher's LSD test from the first 10-day block (T1), p < 0.05.

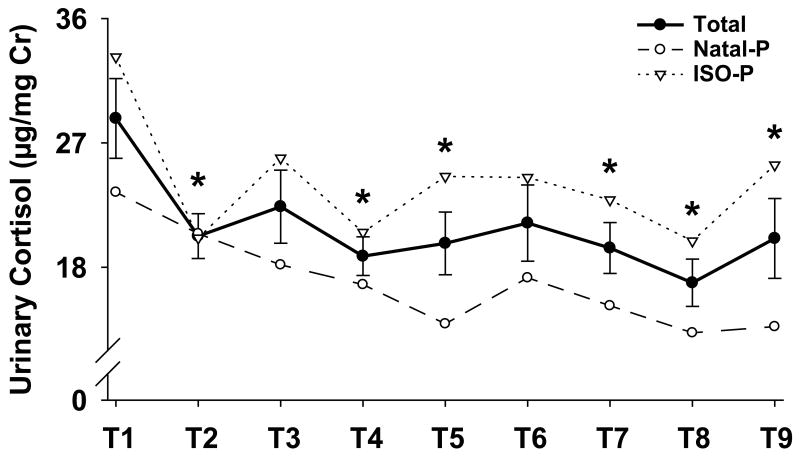

3.2. Excreted urinary cortisol during cohabitation

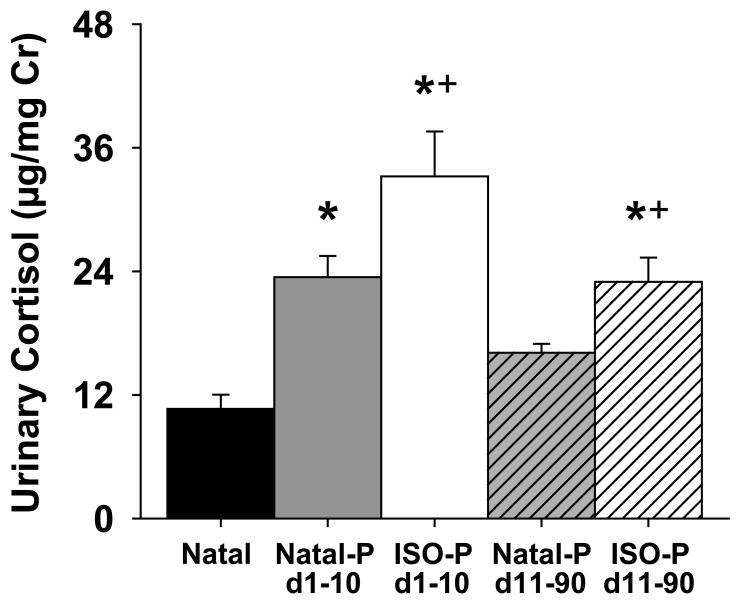

Overall, urinary cortisol levels were highest during the first 10-days of pairing, dropping significantly during the second 10-day block and persisting at these lower levels throughout the rest of the pairing period, [see Fig. 3; F (8,56) = 4.07, p < 0.001]. There was also a difference in urinary cortisol levels between the two pairing groups such that ISO-P marmosets had significantly higher cortisol levels after pairing than Natal-P marmosets throughout the 90-day pairing period, [see Table 1; F (1,7) = 6.95, p < 0.05]. In addition, urinary cortisol levels during the first 10-days and subsequent 80-days (Days 11-90) of pairing for ISO-P and Natal-P marmosets were compared to basal cortisol levels sampled from Natal marmosets during a 10-day period. Urinary cortisol levels were higher in all marmosets during the first 10-days of pairing, with cortisol levels higher in ISO-P marmosets than Natal-P marmosets, [see Fig. 4; F (2,16) = 16.52, p < 0.0001]. In contrast, only urinary cortisol levels of ISO-P marmosets during the subsequent 80-days of pairing remained significantly higher than Natal marmosets, with cortisol levels remaining higher in ISO-P marmosets than Natal-P marmosets, [see Fig. 4; F (2,16) = 10.62, p < 0.001].

Fig. 3.

Urinary cortisol concentrations (mean ± SEM) during pairing and by prior stress condition. Time periods (T2-T9) labeled with an asterisk differ significantly by post hoc Fisher's LSD test from the first 10-day block (T1), p < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Differences in urinary cortisol concentrations (mean ± SEM) between natal-housed and paired marmosets under different stress conditions and length of pairing. Cortisol during pairing averaged across the first 10-day blocks (open bars) and the subsequent 80-days (hashed bars) for ISO-P (white bars) and Natal-P (grey bars) marmosets or averaged during a 10-day block for age-matched Natal marmosets (black bar). Bars labeled with an asterisk or a plus sign differ significantly by post hoc Fisher's LSD test from Natal marmosets or Natal-P marmosets during the same period, respectively, p < 0.05.

3.3. Correlation between sociosexual behavior and cortisol

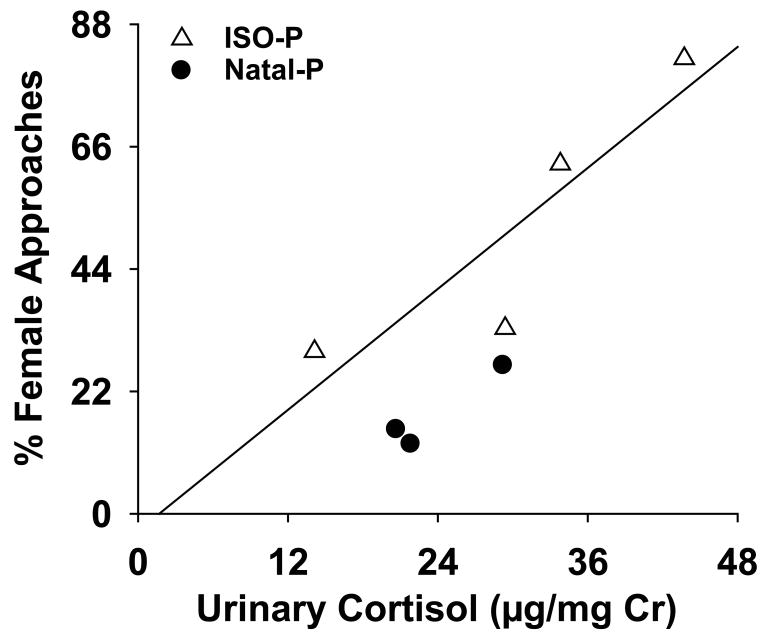

When marmoset behavior during the first 10 days of pairing was compared to urinary cortisol levels during this same time period, only female contact behavior was associated with urinary cortisol levels, [see Fig. 5; r = 0.84, p < 0.05]. Specifically, the percentage of approaches between the pair that was attributed to the female was positively associated with the urinary cortisol level such that females with high cortisol levels had a higher percentage of approaches than females with low cortisol levels. However, cortisol levels during the first 10 days of pairing were not correlated to female contact behavior during any of the subsequent time periods nor any other behaviors. Male cortisol during the first 10-day block was not associated with any behaviors.

Fig. 5.

Female approaches (% female/total approaches) correlation with urinary cortisol concentrations (μg/mg Cr) during the first 10 days of pairing, p < 0.05. ISO-P and Natal-P females are indicated with open triangles and closed circles, respectively.

4. Discussion

Social bonds between two individuals form during high sociosexual interactions [reviewed in 1] and can be influenced by prior life experiences, including stressful life events [reviewed in 66]. In this study, prior social isolation seemed to influence some social and contact behaviors and the HPA axis activity, as measured by urinary cortisol levels. ISO-P marmosets were in close proximity to their social partners almost twice as often and tended to groom their partner more often than Natal-P marmosets throughout the 90 days of pairing. Cortisol levels were elevated in marmosets during the initial 10-days of pairing compared to marmosets living in their natal group. During the subsequent period (pairing days 10-90), cortisol levels dropped significantly, though the cortisol levels of ISO-P marmosets remained higher than Natal-P marmosets. Thus, the social instability of pair formation may lead to a transient increase in HPA axis activity while social isolation results in a prolonged HPA axis dysregulation. In addition, female social contact behavior was associated with higher cortisol levels at the onset of pairing. Thus, the heightened social contact during interactions with a new social partner may be enhanced by activation of the HPA axis, or a moderating factor, in female marmoset but not males.

During the first 90 days of pairing, male and female Geoffroy's tufted-ear marmosets demonstrated a dissociated pattern of social and sexual behavior that is common among these primate taxa. Social contact and sexual behavior seems to be transiently high during the onset of pairing, while social behavior is linearly stable. Particularly, social proximity and sexual solicitations between the pair and male sexual behavior occurred often during the first 10-days of pairing but quickly dropped to negligible levels thereafter, similar to reported sexual activity in newly paired common (C. jacchus), Wied's tufted-eared (C. kuhlii) and black tufted-eared (C. penicillata) marmosets [35, 37, 67]. In comparison, social behavior displayed by males and females was maintained at a constant throughout the 90 days of observed pairing. In other callitrichines primates, partner-directed social behavior such as allogrooming and food sharing tends to either remain constant or become more frequent during this early period of cohabitation [35, 37, 67–69]. The independence in the sexual and social behaviors suggests that there may be different mechanisms governing the sexual versus social relationships in marmosets.

Prior stressful life events can influence the sociability of an individual and the formation of new social bonds. Studies on both humans and nonhuman animals have documented an increase in proximity-seeking behavior during a reunion with a social partner after periods of social separation [13, 70–73]. For example, after a 7-hr separation, female marmosets played a greater role in maintaining proximity with their social partner (e.g., increased approaches and reduced leaves) than before they were separated [72]. In kind, social isolation seems to promote proximity-seeking behavior during the establishment of new social bonds. In the current study, ISO-P marmosets increased the time spent in social contact with and grooming of their social partner throughout the pairing period compared to Natal-P marmosets. Social isolation includes both the anxiety of uncertainty and the loss of social partners. Thus, social isolation may promote proximity-seeking and other social behaviors as a mechanism of coping with the instable social environment.

Social isolation can evoke stress physiology in marmosets [3, 72, 74], and the activation of such pathways, like the HPA axis, may influence social behavior required for pair formation. In the current study, cortisol levels were higher in ISO-P marmosets than Natal-P marmosets. In addition, female social contact behavior was associated with their cortisol levels. Specifically, females with higher cortisol levels (typically ISO-P females) during the first 10-days of pairing tended to establish contact with their male partner more often than females with lower cortisol levels (typically Natal-P females). It is worth considering potential factors that could be moderating the effects of cortisol levels and social contact behavior during pairing. Oxytocin promotes social contact and affiliative behaviors and is released during stressful experience, reducing stress physiology [59, 75–80]. Recently, we documented that intranasal administration of oxytocin during pair formation promotes social contact and affiliative behavior in marmosets, while administration of an oxytocin receptor antagonist limits these behaviors [60]. Therefore, there may be a role for oxytocin as a moderating factor in the effects of the HPA axis on partner-directed social behavior during pairing in marmosets.

During pairing, cortisol may also be affected by social buffering, an attenuation of the biobehavioral response to a stressful event by the presence of, or interactions with, a social partner [16]. Social buffering is commonly observed in species that create attachment-like bonds between adult breeding partners [e.g., humans: 17; titi monkeys: 21; prairie voles: 22; guinea pigs: 23]. For example, sexually naïve female prairie voles, a socially monogamous rodent, experience a reduction in corticosterone concentrations within the first hour of cohabitation with a novel male but not a novel female conspecifics [29]. Male prairie voles housed for three days with a novel female have lower corticosterone concentrations than males housed with a same-sex conspecific [81]. In primates, female marmosets that are removed from their natal family and single-housed for long time periods display elevated urinary cortisol levels [50]. Upon pairing with a novel male, cortisol levels drop to levels similar to while in the natal group. Yet, it is not clear if the drop is associated with pairing with a male or the timing of separation. In the current study, Natal-P marmosets displayed a transient elevation in cortisol at the onset of pairing. In contrast, ISO-P marmosets had substantially higher cortisol levels upon pairing, and exhibited a significant drop in cortisol after pairing. Female cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus), a related callitrichine primate, that are removed from their natal group and housed adjacent to a novel, unrelated male have a sustained increase in urinary cortisol levels [82]. Therefore, the activation of the HPA axis that is associated with departure from a natal group – potentially from the loss of a social group or an unstable social environment – seems to be mitigated by interaction with rather than the mere presence of a new social partner in callitrichine primates.

In summary, among the array of biological factors that influence the dynamics of pair bonds, glucocorticoids modify certain pair bonding behaviors in monogamous rodents [e.g., prairie voles: reviewed in 29, 83] and are implicated in social relationships of primates. For marmosets, the formation of a new social group with a receptive partner typically requires males and females to emigrate from their natal group, creating an unstable and potentially stressful or arousing circumstance and activating the HPA axis. While disruption to the social environment can be distressing, in many cases, the consequences of HPA axis function is to arouse the system to different types of stimuli that are associated with changes in the social environment, and these changes are not always negative. Thus, marmosets may naturally experience a state of arousal or anxiety as they attempt to form new social bonds [50, 51]. This heightened state of arousal and the negative effects of prolonged isolation on mental and physical health [e.g., 5, 7, 26, 48, 70, 72] may add to the initial draw to forming these bonds, either through the HPA axis function or a moderating factor like oxytocin. In other primate species, cortisol levels in high ranking group members typically elevate during periods of unstable social environment and subsequently drop during periods of social stability [e.g., 84–86]. This is likely a function of high ranking group members ability to predict and manage the social environment during stable and unstable periods, varying allostatic load [reviewed by 87]. In marmoset social systems, the breeding male and female are dominant to all other group members [88], and social instability (e.g., social isolation or separation) can lead to increased HPA axis function [48]. As the social environment becomes more stable and social bonds are formed in marmosets, the homeostatic state may again change – reflected by a drop in circulating cortisol concentrations – to reflect this more stable social environment, in accordance with other primate species.

Highlights.

The social instability associated with establishing a social pairing led to a transient increase in cortisol levels.

Social isolation resulted in a prolonged HPA axis dysregulation in the pairing period.

Social isolation increased contact behavior with a new social partner.

Female social contact behavior was associated with higher cortisol levels at the onset of pairing.

Acknowledgments

Some of these findings were presented as a poster presentation at the 32nd annual meeting of the American Society of Primatologists, September 2009. The research was supported by funds awarded to Adam S. Smith from the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship and Jeffrey A. French from the National Institutes of Health (HD-042882) and NSF (IBN 00-91030).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kleiman DG. Monogamy in mammals. Q Rev Biol. 1977;52:39–69. doi: 10.1086/409721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendoza SP, Hennessy MB, Lyons DM. Distinct immediate and prolonged effects of separation on plasma cortisol in adult female squirrel monkeys. Psychobiology. 1992;20:300–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith TE, McGreer-Whitworth B, French JA. Close proximity of the heterosexual partner reduces the physiological and behavioral consequences of novel-cage housing in black tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix kuhlii) Horm Behav. 1998;34:211–22. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westenbroek C, Den Boer JA, Veenhuis M, Ter Horst GJ. Chronic stress and social housing differentially affect neurogenesis in male and female rats. Brain Res Bull. 2004;64:303–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasper ER, DeVries AC. Social structure influences effects of pair-housing on wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grippo AJ, Cushing BS, Carter CS. Depression-like behavior and stressor-induced neuroendocrine activation in female prairie voles exposed to chronic social isolation. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:149–57. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802f054b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grippo AJ, Gerena D, Huang J, Kumar N, Shah M, Ughreja R, et al. Social isolation induces behavioral and neuroendocrine disturbances relevant to depression in female and male prairie voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:966–80. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Social isolation disrupts autonomic regulation of the heart and influences negative affective behaviors. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamond LM, Hicks AM, Otter-Henderson KD. Every time you go away: Changes in affect, behavior, and physiology associated with travel-related separations from romantic partners. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95:385–403. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosch OJ, Nair HP, Ahern TH, Neumann ID, Young LJ. The CRF system mediates increased passive stress-coping behavior following the loss of a bonded partner in a monogamous rodent. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1406–15. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan Y, Liu Y, Young KA, Zhang Z, Wang Z. Post-weaning social isolation alters anxiety-related behavior and neurochemical gene expression in the brain of male prairie voles. Neurosci Lett. 2009;454:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.02.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norman GJ, Karelina K, Morris JS, Zhang N, Cochran M, DeVries AC. Social interaction prevents the development of depressive-like behavior post nerve injury in mice: A potential role for oxytocin. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:519–26. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181de8678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson J, Rholes W. Stress and secure base relationships in adulthood. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Attachment processes in adulthood. London, PA: Jessica Kingsley; 1994. pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seeman TE. Social ties and health: The benefits of social integration. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:442–51. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller G. Social neuroscience. Why loneliness is hazardous to your health. Science. 2011;331:138–40. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6014.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirschbaum C, Klauer T, Filipp SH, Hellhammer DH. Sex-specific effects of social support on cortisol and subjective responses to acute psychological stress. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:23–31. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powers SI, Pietromonaco PR, Gunlicks M, Sayer A. Dating couples' attachment styles and patterns of cortisol reactivity and recovery in response to a relationship conflict. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90:613–28. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerber P, Anzenberger G, Schnell CR. Behavioral and cardiophysiological responses of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) to social and environmental changes. Primates. 2002;43:201–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02629648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rukstalis M, French JA. Vocal buffering of the stress response: Exposure to conspecific vocalizations moderates urinary cortisol excretion in isolated marmosets. Horm Behav. 2005;47:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendoza SP, Mason WA. Parental division of labour and differentiation of attachments in a monogamous primate (Callicebus moloch) Anim Behav. 1986;34:1336–47. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeVries AC, Glasper ER, Detillion CE. Social modulation of stress responses. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sachser N, Dürschlag M, Hirzel D. Social relationships and the management of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:891–904. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro WLR, Matt KS. Neuroendocrine correlates of separation stress in the Siberian dwarf hamster (Phodopus sungorus) Physiol Behav. 1997;61:477–84. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reburn CJ, Wynne-Edwards KE. Hormonal changes in males of a naturally biparental and a uniparental mammal. Horm Behav. 1999;35:163–76. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Detillion CE, Craft TKS, Glasper ER, Prendergast BJ, DeVries AC. Social facilitation of wound healing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1004–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chauke M, Malisch JL, Robinson C, de Jong TR, Saltzman W. Effects of reproductive status on behavioral and endocrine responses to acute stress in a biparental rodent, the California mouse (Peromyscus californicus) Horm Behav. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.04.002. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowlby J. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books; 1973. Attachment and loss. [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeVries AC, DeVries MB, Taymans SE, Carter CS. Modulation of pair bonding in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) by corticosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7744–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeVries C, Taymans SE, Carter CS. Social modulation of corticosteroid responses in male prairie voles. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;807:494–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jolly A. The evolution of primate behavior. 2nd. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW. Primate societies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Schaik CP, Dunbar RIM. The evolution of monogamy in large primates: A new hypothesis and some crucial tests. Behaviour. 1990;115:30–62. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexander RD. The evolution of social behavior. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1974;5:325–83. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans S, Poole TB. Pair-bond formation and breeding success in the common marmoset Callithrix jacchus jacchus. Int J Primatol. 1983;4:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buchanan-Smith HM, Jordan TR. An experimental investigation of the pair bond in the callitrichid monkey, Saguinus labiatus. Int J Primatol. 1992;13:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaffner CM, Shepherd RE, Santos CV, French JA. Development of heterosexual relationships in Wied's black tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix kuhlii) Am J Primatol. 1995;36:185–200. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350360303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Epple G. Sex differences in partner preference in mated pairs of saddle-back tamarins (Saguinus fuscicollis) Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1990;27:455–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inglett BJ, French JA, Dethlefs TM. Patterns of social preference across different social contexts in golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia) J Comp Psychol. 1990;104:131–9. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.104.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts RL, Uri EM, Newman JD. Delayed pair bond formation in common marmosets: Sex is not enough. Am J Primatol. 1999;49:93. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epple G. Notes on the establishment and maintenance of the pair bond in Saguinus fuscicollis. In: Kleiman DG, editor. The biology and conservation of the Callitrichidae. Washington, D. C.: Smithson-Jan Institution Press; 1977. pp. 251–70. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epple G. Lack of effect of castration on scent marking, displays and aggression in a South American primate (Saguinus fuscicollis) Horm Behav. 1978;11:139–50. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(78)90043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.French JA, Snowdon CT. Sexual dimorphism in response to unfamiliar intruders in the tamarin, Saguinus oedipus. Anim Behav. 1981;29:822–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.French JA, Inglett BJ. Female-female aggression and male indifference in response to unfamiliar intruders in lion tamarins. Anim Behav. 1989;37:487–97. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker AJ, Dietz JM. Immigration in wild groups of golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia) Am J Primatol. 1996;38:47–56. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1996)38:1<47::AID-AJP5>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrari SF, Digby LJ. Wild Callithrix groups: Stable extended families? Am J Primatol. 1996;38:19–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1996)38:1<19::AID-AJP3>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sousa MBC, Albuquerque ACSR, Yamamoto ME, Araújo A, Arruda MF. Emigration as a reproductive strategy of the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) In: Ford SM, Porter LM, Davis LC, editors. The smallest anthropoids: The marmoset/callimico radiation. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 167–82. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson EO, Kamilaris TC, Carter CS, Calogero AE, Gold PW, Chrousos GP. The biobehavioral consequences of psychogenic stress in a small, social primate (Callithrix jacchus jacchus) Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:317–37. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaffner CM. Social and endocrine factors in the establishment and maintenance of sociosexual relationships in Wied's black tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix kuhli) [PhD] Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska at Omaha; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith TE, French JA. Social and reproduction conditions modulate urinary cortisol excretion in black tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix kuhli) Am J Primatol. 1997;42:253–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1997)42:4<253::AID-AJP1>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ziegler TE, Sousa MBC. Parent-daughter relationships and social controls on fertility in female common marmosets, Callithrix jacchus. Horm Behav. 2002;42:356–67. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roney JR, Lukaszewski AW, Simmons ZL. Rapid endocrine responses of young men to social interactions with young women. Horm Behav. 2007;52:326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.López HH, Hay AC, Conklin PH. Attractive men induce testosterone and cortisol release in women. Horm Behav. 2009;56:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Meij L, Buunk AP, Salvador A. Contact with attractive women affects the release of cortisol in men. Horm Behav. 2010;58:501–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marazziti D, Canale D. Hormonal changes when falling in love. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:931–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baker JV, Abbott DH, Saltzman W. Social determinants of reproductive failure in male common marmosets housed with their natal family. Anim Behav. 1999;58:501–13. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ross CN, French JA, Patera KJ. Intensity of aggressive interactions modulates testosterone in male marmosets. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:437–45. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schaffner CM, French JA. Behavioral and endocrine responses in male marmosets to the establishment of multimale breeding groups: Evidence for non-monopolizing facultative polyandry. Int J Primatol. 2004;25:709–32. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carter CS. Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:779–818. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith AS, Ågmo A, Birnie AK, French JA. Manipulation of the oxytocin system alters social behavior and attraction in pair-bonding primates, Callithrix penicillata. Horm Behav. 2010;57:255–62. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Norcross JL, Newman JD. Social context affects phee call production by nonreproductive common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) Am J Primatol. 1997;43:135–46. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1997)43:2<135::AID-AJP3>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith AS, Birnie AK, Lane KR, French JA. Production and perception of sex differences in vocalizations of Wied's black-tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix kuhlii) Am J Primatol. 2009;71:324–32. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.French JA, Brewer KJ, Schaffner CM, Schalley J, Hightower-Merritt D, Smith TE, et al. Urinary steroid and gonadotropin excretion across the reproductive cycle in female Wied's black tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix kuhlii) Am J Primatol. 1996;40:231–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1996)40:3<231::AID-AJP2>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tietz NW. Fundamentals of clinical chemistry. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith TE, French JA. Psychosocial stress and urinary cortisol excretion in marmoset monkeys. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:225–32. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.DeVries AC, Craft TKS, Glasper ER, Neigh GN, Alexander JK. 2006 Curt P. Richter award winner: Social influences on stress responses and health. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:587–603. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Woodcock AJ. The first weeks of cohabitation of newly-formed heterosexual pairs of common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) Folia Primatol. 1982;37:228–54. doi: 10.1159/000156035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruiz J. Comparison of affiliative behaviors between old and recently established pairs of golden lion tamarin, Leontopithecus rosalia. Primates. 1990;31:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Silva HPA, Sousa MBC. The pair-bond formation and its role in the stimulation of reproductive function in female common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) Int J Primatol. 1997;18:387–400. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shepherd RE, French JA. Comparative analysis of sociality in lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia) and marmosets (Callithrix kuhli): Responses to separation from long-term pairmates. J Comp Psychol. 1999;113:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Depue RA, Morrone-Strupinsky JV. A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding: Implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28:313–50. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.French JA, Fite JE, Jensen HA, Oparowski KM, Rukstalis M, Fix H, et al. Treatment with CRH-1 antagonist antalarmin reduces behavioral and endocrine responses to social stressors in marmosets (Callithrix kuhlii) Am J Primatol. 2007;69:877–89. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adrian O, Kaiser S, Sachser N, Jandewerth P, Löttker P, Epplen JT, et al. Female influences on pair formation, reproduction and male stress responses in a monogamous cavy (Galea monasteriensis) Horm Behav. 2008;53:403–12. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Norcross JL, Newman JD. Effects of separation and novelty on distress vocalizations and cortisol in the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) Am J Primatol. 1999;47:209–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1999)47:3<209::AID-AJP3>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Legros JJ, Chiodera P, Geenen V, von Frenckell R. Confirmation of the inhibitory influence of exogenous oxytocin on cortisol and ACTH in man: Evidence of reproducibility. Acta Endocrinol. 1987;114:345–9. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1140345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jezová D, Michajlovskij N, Kvetnanský R, Makara GB. Paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus are not equally important for oxytocin release during stress. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:776–81. doi: 10.1159/000126436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cho MM, DeVries AC, Williams JR, Carter CS. The effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on partner preferences in male and female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:1071–80. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.5.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neumann ID, Wigger A, Torner L, Holsboer F, Landgraf R. Brain oxytocin inhibits basal and stress-induced activity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in male and female rats: Partial action within the paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:235–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bosch OJ, Krömer SA, Brunton PJ, Neumann ID. Release of oxytocin in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, but not central amygdala or lateral septum in lactating residents and virgin intruders during maternal defence. Neuroscience. 2004;124:439–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ditzen B, Schaer M, Gabriel B, Bodenmann G, Ehlert U, Heinrichs M. Intranasal oxytocin increases positive communication and reduces cortisol levels during couple conflict. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:728–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Campbell JC, Laugero KD, Van Westerhuyzen JA, Hostetler CM, Cohen JD, Bales KL. Costs of pair-bonding and paternal care in male prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Physiol Behav. 2009;98:367–73. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ziegler TE, Scheffler G, Snowdon CT. The relationship of cortisol levels to social environment and reproductive functioning in female cotton-top tamarins, Saguinus oedipus. Horm Behav. 1995;29:407–24. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1995.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.DeVries AC. Interaction among social environment, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and behavior. Horm Behav. 2002;41:405–13. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chamove AS, Bowman RE. Rhesus plasma cortisol response at four dominance positions. Aggressive Behav. 1978;4:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Setchell JM, Smith T, Wickings EJ, Knapp LA. Stress, social behaviour, and secondary sexual traits in a male primate. Horm Behav. 2010;58:720–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sapolsky RM. Why zebras don't get ulcers: An updated guide to stress, stress related diseases, and coping. 2nd. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abbott DH, Keverne EB, Bercovitch FB, Shively CA, Mendoza SP, Saltzman W, et al. Are subordinates always stressed? A comparative analysis of rank differences in cortisol levels among primates. Horm Behav. 2003;43:67–82. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rylands AB. Marmosets and tamarins: Systematics, behavior, and ecology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]