Abstract

Objective

Growth arrest and DNA damage inducible 45β (Gadd45β) is involved in stress responses, cell cycle regulation, and oncogenesis. Previous studies demonstrated that Gadd45β deficiency exacerbates K/BxN serum-induced arthritis and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) in mice, indicating that Gadd45β plays a suppressive role in innate and adaptive immune responses. To further understand how Gadd45β regulates autoimmunity, we evaluated collagen-induced arthritis in Gadd45β−/− mice.

Methods

Wildtype and Gadd45β−/− DBA/1 mice were immunized with bovine type II collagen (CII). Serum anti-collagen antibody levels were quantified by ELISA. Cytokines and matrix metalloproteinase expression in the joint and spleen was determined by quantitative PCR. In-vitro T cell cytokine response to CII was measured by multiplex analysis. CD4+CD25+Treg and Th17 cells were quantified using flow cytometry.

Results

Gadd45β−/− mice showed significantly lower arthritis severity and joint destruction compared with WT mice. MMP3 and MMP13 expression was also markedly reduced in Gadd45β−/− mice. However, serum anti-CII antibody levels were similar in both groups. Foxp3 and IL-10 expression was increased 2–3-fold in arthritic Gadd45β−/− splenocytes compared with WT. Flow cytometric analysis showed greater numbers of CD4+CD25+Treg cells in Gadd45β−/− spleen than in WT. In-vitro studies showed that interferon-γ and interleukin-17 production by T cells was significantly decreased in Gadd45β−/− mice.

Conclusion

Unlike in passive K/BxN arthritis model and EAE, Gadd45β-deficiency in CIA was associated with lower arthritis severity, elevated IL-10 expression, decreased IL-17 production, and increased numbers of Treg cells. The data suggest that Gadd45β plays a complex role in regulating adaptive immunity and, depending on the model, either enhances or suppresses inflammation.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease marked by synovial lining hyperplasia, chronic synovitis and progressive matrix damage (1). The mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases are thought to play a role in the disease by virtue of their ability to regulate cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (2–4). c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), which is one of the MAP kinases, is a potential therapeutic target and selective inhibitors suppress synovitis and joint destruction in rat adjuvant arthritis (5). More recently, JNK1 was shown to be the responsible for inflammation in murine arthritis by virtue of its critical role in mast cell degranulation (6). Of the upstream kinases involved in the JNK pathway, MKK7 is especially important and is primarily responsible for phosphorylating JNK in cultured fibroblast-like synoviocytes (7).

Based on the role of MKK7 and JNK in arthritis, we recently evaluated the role of anendogenous MKK7 inhibitor, namely Growth Arrest and DNA Damage inducible genes-ß (Gadd45β) in the passive K/BxN serum transfer model of arthritis (8). Gadd45β deficiency markedly increased JNK activation and clinical arthritis, suggesting that strategies to enhance Gadd45β expression might be beneficial in RA. Gadd45β also regulates T cell differentiation and activation (9–11). For instance, Gadd45β contributes to initiating Th1 cell differentiation by enhancing the expression of T-bet and also affects persistent p38 activation mediated by T cell receptor ligation (12, 13). An overall suppressive role of Gadd45β in adaptive immunity was demonstrated in studies using Gadd45β deficient mice, which have increased disease severity in murine experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE)(11).

To understand the role of Gadd45β in an adaptive immunity model of RA, we studied collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) in Gadd45β deficient mice. Based on the results in EAE and the passive K/BxN model, we predicted that the mice would have increased disease severity. Surprisingly, Gadd45β−/− mice had significantly lower arthritis scores and decreased joint destruction compared with wild type (WT) mice. The mechanism was associated with decreased production of IL-17, increased expression of the suppressive cytokine IL-10, and increased numbers of regulatory T cells (Tregs). These unexpected findings suggest that Gadd45β can have the diametrically opposing effects in inflammation and autoimmunity models depending on the relative contributions of innate and adaptive immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

DBA/1 Gadd45β−/− mice were generated by backcrossing C57B/6 Gadd45β−/− mice with DBA/1 mice. Background was confirmed using speed congenics (Charles River, Wilmington, MA). Mice used in these experiments were 6–8 weeks old. All animal experiments were carried out according to protocols by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of the University of California, San Diego.

Collagen-induced arthritis

WT and Gadd45β−/− mice were immunized at the base of the tail with 100 μg of immunization-grade bovine type II collagen in Freund’s complete adjuvant (Chondrex, Redmond, WA) as previously described (14). On day 21, mice were boosted with an intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg of bovine type II collagen in 100 μl of PBS. On day 28, 5 μg of LPS was intraperitoneally injected to synchronize disease onset. The clinical severity of arthritis was assessed using a semi-quantitative clinical scoring system for each paw: 0 = normal, 1 = erythema and mild swelling in the ankle/wrist, 2 = erythema and mild swelling extending from the ankle/wrist to the mid-hind paw/mid-forepaw, 3 = erythema and moderate swelling extending from the ankle/wrist to the metatarsophalangeal or metacarpophalangeal joints, and 4 = erythema and severe swelling of the entire paw, including the digits. The arthritis score for each mouse was the sum of all paw scores (the maximum total score per mouse was 16).

Histologic assessment

The hind paws were removed on day 55 and fixed in 10 % formalin solution for 24 hours, decalcified in EDTA and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to determine proteoglycan content. Histopathological changes in tarsal joints were measured using a semi-quantitative scoring system to assess synovial inflammation, extra-articular inflammation and bone erosion as previously described (0–4 scale; maximum score per mouse was 12) (15).

Measurement of serum anti-type II collagen antibodies

Blood was collected from WT and Gadd45β−/− mice on day 20 or 55 at the time of sacrifice. Anti-type II collagen total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies in serum were quantified using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Chondrex).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA isolated from snap frozen joint or spleen was performed as described previously (16). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with Assays-on-Demand gene expression products (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Threshold cycle (Ct) values were used to calculate the number of cell equivalents (CE) in the test samples using a standard cDNA curve. The data were normalized to Hprt1 expression to obtain relative cell expression units (REU).

Western blot analysis

Ankle joints from WT and Gadd45b−/− mice (day 55) were snap-frozen, pulverized, and protein was extracted using modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1.0 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na2VO4, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μM pepstatin A, 1 mM PMSF) (17). Whole tissue lysates were fractionated by Tris-glycine buffered 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes followed by incubation with anti- P-JNK, JNK, P-p38, p38 and GAPDH antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactive protein was detected with Immune-Star WesternC Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using VersaDoc MP4000 imaging system (Bio-Rad). The densitometry analysis was performed using Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production

WT and Gadd45β−/− mice were immunized with CII. On day 10, the mice were sacrificed and lymph nodes (LN) were harvested. Single cell suspensions were prepared as previously described (18). Cells were cultured in 96-well flat-bottomed plates in triplicate at a density of 5×105 cells/well (200 μl/well) in medium or with 50 μg/ml of CNBr cleaved collagen II (Chondrex, Redmond, WA) for 72 hr at 37°C in 5% CO2. For proliferation assays, 1 μCi of [3H] thymidine solution was added into wells and incubated for an additional 24 hr. The cells were harvested and [3H]-thymidine incorporation was determined using scintillation counter. Culture supernatants were harvested after 72 hr of CII stimulation and cytokines were assayed by multiplex bead analysis (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Flow cytometry

Spleens were harvested from arthritis mice on day 55 and splenocytes were isolated as above. 1×106 cells were washed with FACS buffer (PBS containing 0.1% NaN3 and 1% bovine serum albumin) and stained with APC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for CD4 (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) and PE-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for CD25 (BD Pharmingen) in the dark for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed three times and flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur instrument and analyzed with CellQuest software (UCSD Moores Cancer Center). For Th17 polarizing conditions, splenocytes were cultured in complete Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium with TGF-β (3ng/ml) and IL-6 (20ng/ml) along with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies (145-2C11 and 37.51, respectively, (10μg/ml) BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). After 72h, the cells were stimulated for 4h with phorbol myristate acetate (50ng/ml) and ionomycin (1μg/ml) in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences). The cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD4, IL-17A, IFNγ and IL-4 antibody cocktail (Mouse Th1/Th2/Th17 phenotyping kit, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparison of multiple groups was performed using one-way or two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test or Student’s t-test for comparison of two groups. p values less than 0.05 was statistically significant.

RESULTS

CIA in WT and Gadd45β−/− mice

Our previous studies showed that arthritis severity was increased in Gadd45β-deficient mice in the passive K/BxN serum transfer model (8). To determine the role of Gadd45β in a chronic model of adaptive immunity, we evaluated CIA in Gadd45β−/− mice. Surprisingly, the disease severity was significantly decreased in Gadd45β−/− mice (Figure 1A) (p<0.01). Histologic evaluation of joints on day 55 showed marked reduction in synovial inflammation, extra-articular inflammation, and bone erosions in Gadd45β−/− compared with WT mice (p<0.05) (Figure 1B, C).

Figure 1.

Clinical arthritis scores in WT and Gadd45β−/− DBA/1 mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA). A. Arthritis was evaluated using a semiquantitative scoring system. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Clinical arthritis scores were significantly lower in Gadd45β−/− mice than WT mice (n=19 in each group, p < 0.05). B, Histology scores were significantly lower in Gadd45β−/− mice compared with WT (*p<0.05). C, Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of ankles obtained on day 55 from CIA mice.

JNK and p38 activation in Gadd45β−/− mice

We had previously shown that Gadd45β−/− mice have increased JNK activation in passive K/BxN arthritis (8). Therefore, our initial mechanistic studies in CIA evaluated whether Gadd45β deficiency was associated with changes in P-JNK due to ability of Gadd45β to block MKK7 function. Surprisingly, P-JNK and P-p38 levels were similar in WT and Gadd45β−/− mice arthritic joints on day 55 (Figure 2). Therefore, decreased disease severity in Gadd45β-deficient mice cannot be attributed to inhibition of JNK activation.

Figure 2.

JNK activation in Gadd45β−/− mice. Mice were sacrificed on day 55 and the ankle lysates were evaluated by Western blot analysis. Surprisingly, P-JNK and P-p38 in arthritic joints were similar in WT and Gadd45β−/− mice with CIA.

Anti-type II collagen antibody levels in CIA

We then determined whether the difference in arthritis severity is due to defective generation of pathogenic antibodies. Serum antitype II collagen IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies were measured by solid-phase ELISA. As shown in Figure 3, autoantibody levels were similar in WT and Gadd45β−/− mice on day 20 day or day 55. Therefore, induction of anti-collagen antibody response was not deficient in Gadd45β−/− mice.

Figure 3.

Anti-collagen antibodies in the CIA model. The level of anti-type II collagen antibody in serum was determined on day 20 and day 55. Values are the mean ± SEM μg/ml (n=5 mice at each time point). Differences were not statistically significant between the two groups.

Synovial gene expression in CIA

Using qPCR, we quantified the articular expression of TNF, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-10, MMP3, MMP13 as well as Foxp3 in WT and Gadd45β−/− mice on days 20 and 55 (Figure 4A). MMP3 and MMP13 gene expression was significantly lower in Gadd45β−/− mice than WT mice in the CIA model, which is consistent with decreased arthritis severity (p<0.02). In contrast, expression of TNF, IFN-γ, IL-10, and Foxp3 was similar in arthritic WT and Gadd45β−/− joints. The lack of IL-6 expression is consistent with our earlier studies showing that IL-6 expression peaks relatively early in CIA (19). These results show that Gadd45β deficiency favors joint protection by inhibiting MMPs in CIA.

Figure 4.

Gene expression in CIA. Gene expression in joint and spleen extracts (day 20 and day 55) was determined by real-time qPCR and normalized to Hprt1. Data are expressed as average relative expression units ±SEM. A, Synovial gene expression (Wildtype =WT; −/− = Gadd45β−/−). Note effect on MMP mRNA levels that favor joint destruction in Gadd45β−/− mice. B, Gene expression in the spleen. Expression of IL-10 and Foxp3 was elevated in arthritic Gadd45β−/− mice compared with arthritic WT mice. n=3 for naive mice and n=5–10 for arthritic mice (*p < 0.05, *p < 0.01).

Gene expression profile in Gadd45β−/− splenocytes

Because central immune responses participate in CIA, we also measured gene expression patterns in spleen (Figure 4B). IL-10 expression was significantly increased in arthritic Gadd45β−/− than in WT mice. Levels of Foxp3, expressed by Treg cells, were 2-fold higher in Gadd45β−/− than WT splenocytes (p<0.05). These data suggest that central immunity in Gadd45β deficiency is associated with increased immunosuppressive cytokines and increased numbers of regulatory T cells. The Foxp3 data were confirmed by flow cytometry, which showed increased numbers of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in Gadd45β−/− mice (n=6, p=0.02) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Tregs in Gadd45β-deficient mice. Spleens were harvested from WT and Gadd45β−/− mice on day 55. Splenocytes were stained with APC-CD4 and PE-CD25 antibodies, then analyzed by flow cytometry. The number of splenic CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, but not CD4+ T cells, was significantly higher in Gadd45β−/− than WT mice (n=6, p=0.02). NS = not significant

| Wild type | Gadd45β | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute number of CD4+CD25+Treg cells (×105/spleen) | 17.8±0.8 | 25.3±1.8 | p=0.02 |

| Absolute number of CD 4+ T Cells (×105 spleen) | 112.1±7.3 | 121.9±7.4 | NS |

CII-specific immune response in WT and Gadd45β−/− mice

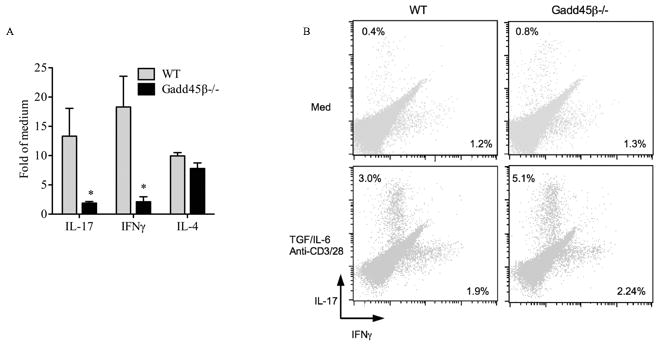

The effect of Gadd45β deficiency on T cells cytokines in CIA led us to evaluate whether antigen-specific T-cell responses might correlate with decreased arthritis severity. LN cells were stimulated in vitro with CII and evaluated for proliferation and cytokine production. There was no significant effect of Gadd45β–deficiency on antigen-stimulated T cell proliferation (data not shown). However, IFN-γ and IL-17 production by antigen stimulated LN cells was significantly decreased in Gadd45β−/− mice compared with WT, while IL-4 production was unchanged (Figure 5A). IL-10 expression was undetectable in both WT and Gadd45β−/− groups at this early time point, which is consistent with its induction and anti-inflammatory function late in the disease model (19). These data suggest that Gadd45β–deficiency suppresses collagen-specific adaptive responses, including Th1 and Th17 function. To determine if Gadd45β is required for Th17 differentiation, WT and Gadd45β−/− splenocytes and LN cells were cultured under Th17 polarizing conditions and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 5B). The frequency of IL-17+ cells was similar in WT and Gadd45β−/− cells, suggesting that Gadd45β does not directly regulate Th17 differentiation.

Figure 5.

Cytokine production by regional lymph node cells from WT and Gadd45β−/− mice. A. Animals were immunized with bovine type II collagen (CII), and 10 days later, lymph node cells were incubated with CII for 72 hr. Cytokine levels in culture supernatants were measured by multiplex bead analysis. Values are the mean ±SEM. n=6 for each group. *p < 0.05 versus WT mice. B, Flow cytometric analysis of splenocytes and LN cells cultured in Th17 polarizing conditions for 72h and stained for CD4, IL-17 and IFNγ. The CD4+ population was analyzed for cytokine expression. The frequency of IL-17+ cells was similar in WT and Gadd45β−/− mice, indicating that Gadd45β is not required for Th17 differentiation.

DISCUSSION

The synovium in RA undergoes striking alterations characterized by inflammatory cell infiltration and synovial lining hyperplasia. Cytokine and MMP expression is markedly increased in the diseased tissue and is associated with activation of MAP kinases and other pro-inflammatory signaling pathways like NF-κB. Gadd45β, which is normally induced by NF-κB, is part of a family of genes implicated in cellular stress responses, cell cycle control and apoptosis (20–22). Gadd45β can serve a counter-regulatory function to cell activation by blocking JNK activation and suppressing inflammation. We recently showed unexpectedly low levels of Gadd45β in RA synovium despite high expression of NF-κB, suggesting that defective Gadd45β expression might contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease (8). The lack of Gadd45β in the synovium, however, was not observed in synovial effusions where the gene is highly expressed in some T cells.

Gadd45β inhibits JNK activation by blocking the interaction of the upstream kinase MKK7 with JNK (23, 24). Therefore, we proposed that enhancing Gadd45β expression might be beneficial in RA. This notion was supported by observations in EAE, where Gadd45β deficient mice had increased neurologic impairment (11). Additional evidence was provided by our studies in passive K/BxN arthritis, where arthritis severity was higher in Gadd45β−/− mice. Mechanistic studies showed that Gadd45β deficiency was associated with higher P-JNK levels in the joint and increased MMP expression in that model (8). Similar increases in signaling and MMP gene expression were observed in cultured synoviocytes from Gadd45β deficient mice.

These data led us to evaluate a more complex model of RA involving adaptive immunity. CIA, unlike passive K/BxN, requires intact T and B cell function with generation of pathogenic anti-type II collagen antibodies and subsequent synovial inflammation. Based on the previous studies, we expected CIA severity, like EAE, to be higher in Gadd45β deficient mice. Surprisingly, Gadd45β− deficiency led to significantly lower arthritis scores throughout the course of the model. Some of the expected downstream sequelae of Gadd45β deficiency, such as increased JNK phosphorylation, were not observed in WT and Gadd45β−/− mice. In addition, B cell suppression was not observed because autoantibody production and class switching did not account for decreased disease severity.

These puzzling results led us to evaluate T cell responses and the gene expression profile of the joint and central lymphoid tissues at both early and late time points. The profiles showed increased production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, especially late in disease, and increased numbers of Tregs in the Gadd45β−/− mice. The source of IL-10 is not known at this time, but could relate to the increased number of Tregs or perhaps, the production by Th2 cells or macrophages in central lymphoid organs. Additional detailed studies evaluating how Gadd45β regulates IL-10 production in the microenvironment are needed to define cell sources and mechanisms of cytokine regulation. In vitro antigen specific responses demonstrated a similar profile, with especially striking suppression of the critical Th17 cytokine IL-17. However, Gadd45β is not an absolute requirement for Th17 differentiation but that the defect probably relates to alterations in the microenvironment. Taken together, these results suggest that Gadd45β plays a pivotal role in antigen-specific T cell responses in CIA and biases the repertoire toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype.

It is not clear why the results for CIA differ from other adaptive immunity models. In EAE, Gadd45β suppresses CD4+ T cell proliferation in response to T cell receptor signaling or cytokines (11, 25), and T cells lacking Gadd45β are more resistant to activation-induced cell death (11, 26). More recent studies suggest that Gadd45β is also required for cytokine production by naive CD4+ T cells and plays a pivotal role in the differentiation of Th1 cells (12, 27). The contribution of Gadd45β to naive CD4+ T cell function has been attributed to its ability to affect sustained p38 activation triggered by TCR or cytokines (12). Furthermore, Gadd45β could also modulate cytokines produced by antigen presenting cells, such as IL-12 and IL-18, which regulates the differentiation of naive T cells into the Th1 phenotype (12, 28).

Therefore, Gadd45β can shape adaptive immune responses and the specific effect depends on the conditions and the environment of the T cells. In some cases, as in EAE, the balance of effects suppresses T cell responses as evidenced by increased disease severity in Gadd45β−/− mice. The reasons for the opposite effect in CIA are not certain, but it could be related to the distinct strains of mice required by the models and the specific T cell subsets that participate. The clear conclusion, however, is that Gadd45β regulation of adaptive immunity is not as simple as originally envisioned.

The implications for RA are also uncertain. The relative lack of Gadd45β and the results in the passive K/BxN model suggested that enhancing Gadd45β would be beneficial. While CIA is not always an accurate representation of RA, the data suggest that we should think carefully about strategies to enhance Gadd45β as a way to suppress JNK activation in a complex disease. The results also might differ depending on the stage of disease, as Gadd45β deficiency could be beneficial early in the process when adaptive immune mechanisms are establishing autoimmunity but detrimental later when synoviocyte or macrophage effector mechanisms play a prominent role. The CIA studies and recent observations showing that targeting JNK directly rather than manipulating Gadd45β expression might be more effective in RA.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health AR047825 (GSF), NIH R01 CA084040 (GF), NIH R01 CA098583 (GF), and Cancer Research UK programme grant C26587/A8839 (GF).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

References

- 1.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423:356–61. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sondergaard BC, Schultz N, Madsen SH, Bay-Jensen AC, Kassem M, Karsdal MA. MAPKs are essential upstream signaling pathways in proteolytic cartilage degradation--divergence in pathways leading to aggrecanase and MMP-mediated articular cartilage degradation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thalhamer T, McGrath MA, Harnett MM. MAPKs and their relevance to arthritis and inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:409–14. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:233–55. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han Z, Boyle DL, Chang L, Bennett B, Karin M, Yang L, et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for metalloproteinase expression and joint destruction in inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guma M, Kashiwakura J, Crain B, Kawakami Y, Beutler B, Firestein GS, et al. JNK1 controls mast cell degranulation and IL-1{beta} production in inflammatory arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22122–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016401107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshizawa T, Hammaker D, Sweeney SE, Boyle DL, Firestein GS. Synoviocyte innate immune responses: I. Differential regulation of interferon responses and the JNK pathway by MAPK kinases. J Immunol. 2008;181:3252–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svensson CI, Inoue T, Hammaker D, Fukushima A, Papa S, Franzoso G, et al. Gadd45beta deficiency in rheumatoid arthritis: enhanced synovitis through JNK signaling. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3229–40. doi: 10.1002/art.24887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ditzel HJ. The K/BxN mouse: a model of human inflammatory arthritis. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asquith DL, Miller AM, McInnes IB, Liew FY. Animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2040–4. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, Tran E, Zhao Y, Huang Y, Flavell R, Lu B. Gadd45 beta and Gadd45 gamma are critical for regulating autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1341–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu B, Ferrandino AF, Flavell RA. Gadd45beta is important for perpetuating cognate and inflammatory signals in T cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:38–44. doi: 10.1038/ni1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju S, Zhu Y, Liu L, Dai S, Li C, Chen E, et al. Gadd45b and Gadd45g are important for anti-tumor immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3010–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han Z, Boyle DL, Manning AM, Firestein GS. AP-1 and NF-kappaB regulation in rheumatoid arthritis and murine collagen-induced arthritis. Autoimmunity. 1998;28:197–208. doi: 10.3109/08916939808995367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamanishi Y, Boyle DL, Pinkoski MJ, Mahboubi A, Lin T, Han Z, et al. Regulation of joint destruction and inflammation by p53 in collagen-induced arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:123–30. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyle DL, Rosengren S, Bugbee W, Kavanaugh A, Firestein GS. Quantitative biomarker analysis of synovial gene expression by real-time PCR. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:R352–60. doi: 10.1186/ar1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammaker DR, Boyle DL, Inoue T, Firestein GS. Regulation of the JNK pathway by TGF-beta activated kinase 1 in rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R57. doi: 10.1186/ar2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simelyte E, Rosengren S, Boyle DL, Corr M, Green DR, Firestein GS. Regulation of arthritis by p53: critical role of adaptive immunity. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1876–84. doi: 10.1002/art.21099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukushima A, Boyle DL, Corr M, Firestein GS. Kinetic analysis of synovial signalling and gene expression in animal models of arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:918–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.112201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papa S, Zazzeroni F, Pham CG, Bubici C, Franzoso G. Linking JNK signaling to NF-kappaB: a key to survival. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5197–208. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin R, De Smaele E, Zazzeroni F, Nguyen DU, Papa S, Jones J, et al. Regulation of the gadd45beta promoter by NF-kappaB. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21:491–503. doi: 10.1089/104454902320219059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vairapandi M, Azam N, Balliet AG, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Characterization of MyD118, Gadd45, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) interacting domains. PCNA impedes MyD118 AND Gadd45-mediated negative growth control. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16810–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.22.16810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papa S, Monti SM, Vitale RM, Bubici C, Jayawardena S, Alvarez K, et al. Insights into the structural basis of the GADD45beta-mediated inactivation of the JNK kinase, MKK7/JNKK2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19029–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papa S, Zazzeroni F, Bubici C, Jayawardena S, Alvarez K, Matsuda S, et al. Gadd45 beta mediates the NF-kappa B suppression of JNK signalling by targeting MKK7/JNKK2. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:146–53. doi: 10.1038/ncb1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu B, Ebensperger C, Dembic Z, Wang Y, Kvatyuk M, Lu T, et al. Targeted disruption of the interferon-gamma receptor 2 gene results in severe immune defects in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8233–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu B. The molecular mechanisms that control function and death of effector CD4+ T cells. Immunol Res. 2006;36:275–82. doi: 10.1385/IR:36:1:275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chi H, Lu B, Takekawa M, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. GADD45beta/GADD45gamma and MEKK4 comprise a genetic pathway mediating STAT4-independent IFNgamma production in T cells. Embo J. 2004;23:1576–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J, Zhu H, Murphy TL, Ouyang W, Murphy KM. IL-18-stimulated GADD45 beta required in cytokine-induced, but not TCR-induced, IFN-gamma production. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:157–64. doi: 10.1038/84264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]